Ukrainian soldiers celebrate at a check point in Bucha, in the outskirts of Kyiv. They had forced the Russian to retreat, but they found evidence of Russian massacres of civilians. (Image: AP)

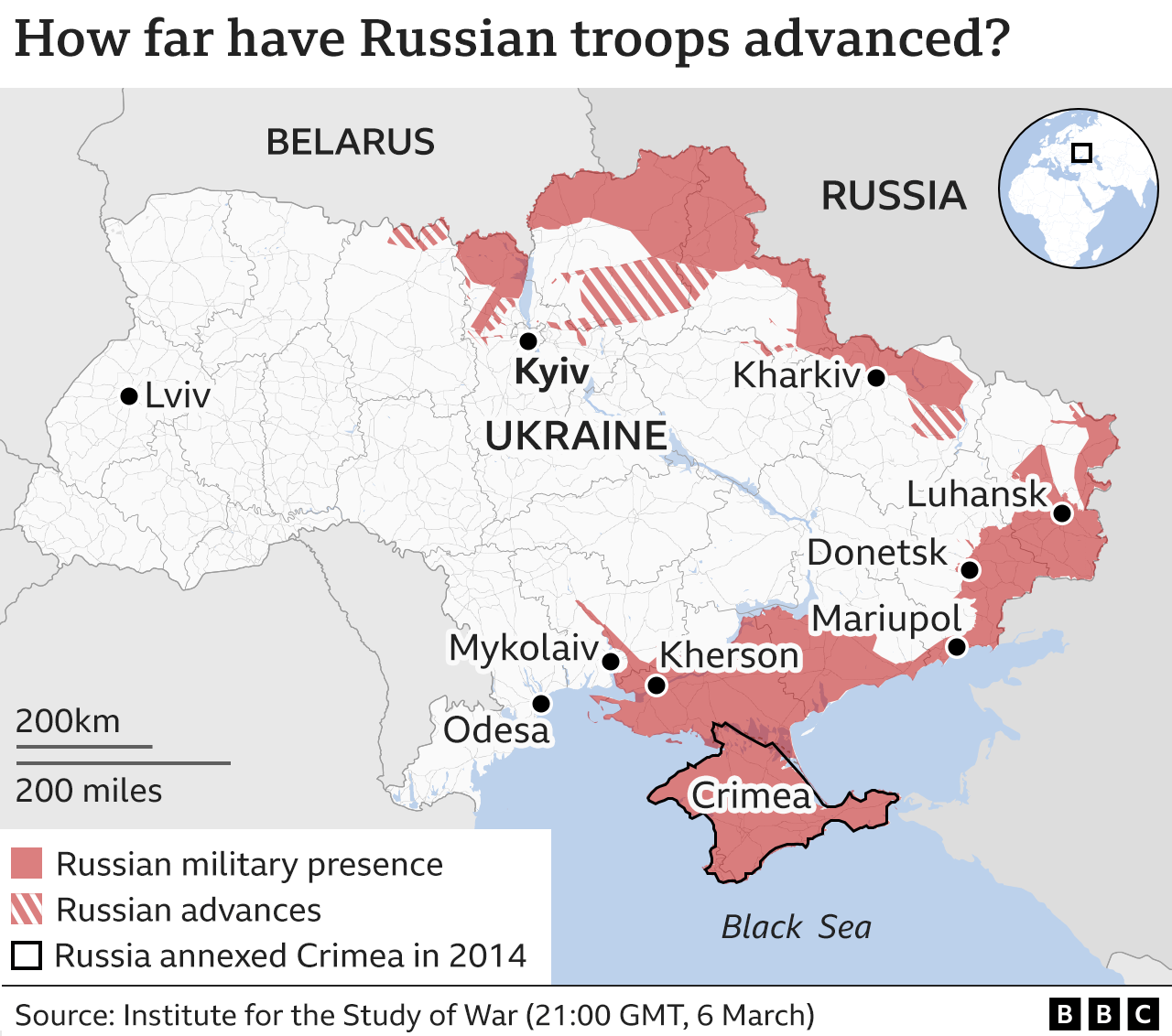

The Ukrainian resistance has won a tremendous victory in defeating the Russian attempt to take Kyiv, both a military victory and moral victory.[1] But much as we admire them for this, Ukraine is far from winning the war. Russia, as it did from the beginning, is a far larger and richer country and has a much larger military and many more planes, ships, and tanks. In purely military terms, without some dramatic change in the situation, it will be nearly impossible for Ukraine to push the Russian army out of the country—but change is, of course, always possible.

Russian troops have retreated in a disorderly fashion, and they are heading to the east, where they will regroup, have an opportunity to rest, be replenished with new troops, and be resupplied with arms and equipment. They will also be joined by Wagner, the Russian pseudo-private army[2] as well as Libyan and Syrian troops and new recruits from Russia.[3]

The Russian retreat from the town around Kyiv and other regions has revealed not only the massive destruction of aerial and artillery bombardment, but also what observers say are massacres of civilians and evidence of cases of rape of Ukrainian women who were then murdered.[4] The horror and revulsion at information about these atrocities has led to calls for investigations by international organizations from the United Nations to the European Union, as well as by several national political leaders and human rights groups.[5] It has also been accompanied by calls for more sanctions[6] and more military equipment for Ukraine, so that such abuses also become a factor in the war. Despite all of these developments, the Russian war against Ukraine remains at an impasse, the central issues of this essay to which we now turn.

The Russian war against Ukraine, according to military experts and press reports, now appears after just a little more than one month to have reached an impasse. This is contrary to the expectations of many, such as General Mark Milley, who in early February told U.S. legislators that if Russia invaded Ukraine, Kyiv would fall in 72-hours.[7] Ukraine has succeeded in thwarting Russia’s plans.

How is it that Ukraine has been able to stop Russian imperialism’s steamroller?[8] What does it mean that we now have a stalemate and how might such a stalemate end? While the political and economic measures taken by the United States, the European Union, and other nations, especially the economic sanctions on Russia, represent an important factor in the war, we concentrate here on the military issues. We hope to provide here information to allow those in the internationalist left to make their own assessment so that we can take the actions—financial and material aid, building support and building an anti-war movement—to help Ukraine win.

We turn now to Frederick W. Kagan who holds a degree from Yale in Russian and Eastern European Studies as well as in military history, has taught as a professor at the West Point Military Academy, a resident scholar at the conservative American Enterprise Institute, and a neocon with expertise in military matters. Obviously, he also sometimes interpolates political advice to the ruling class with which we do not agree, but he and his colleagues at the Institute for the Study of War have insights into military affairs that are useful to those of us on the left. In an article a couple of weeks ago, Kagan wrote: “The initial Russian campaign to invade and conquer Ukraine is coming to an end without having achieved its objectives – in other words, it is being defeated.” The war he wrote has become a “stalemate” whose outcome is unclear.[9] He continues:

The failure of Russia’s initial campaign nevertheless marks an important shift that has implications for the development and execution of Western military, economic and political strategies. The West must continue to provide Ukraine with the weapons it needs to fight, but it must now also significantly expand its aid to help keep Ukraine alive as a country, even under deadlock conditions.

Kagan suggests that we compare Putin’s initial campaign against Ukraine with moments during World War I and with the German invasion of the Soviet Union in June 1941, which also created a long period of impasse.

The stalemate describes a war situation in which neither side can radically change the front lines, no matter how hard it tries….The First World War embodied the impasse…gave rise to very hard fighting with many losses on both sides. The front lines became generally (but not completely) static, with very little movement. There was always a certain movement of lines….but never enough to materially change the situation.[10]

The impasse often involves heavy and bloody battles, such as Somme, Verdun, and Passchendaele in which hundreds of thousands of people were killed but the frontline did not move much. How can such a deadlock be broken? One side can lose its will, one side may gain a technological advantage, or a new ally may enter the war, as in the case of the United States during the First World War, or one side may simply collapse as happened to Russia in 1917. Many things can happen. “This is the most likely scenario we are currently seeing in Ukraine,” writes Kagan.

Our assessment is that the Russian campaign has reached its climax, and that conditions of stalemate are emerging….the Russians do not [have] the ability to bring great effective combat power in a short period of time. The types of mobilizations in which the Russians engage will only generate new combat power in several months at the earliest. Unless something remarkable breaks the impasse we are currently in, the impasse is likely to last for months. Hence our assessment and forecasts.

And of course, we can be wrong. What could happen for this to be the case?[11]

Kagan suggests that changing circumstances could lead to a Russian victory or even a Ukrainian victory, though that seems less likely.

How Is Ukraine Resisting?

Let’s turn to Ukraine and how it is resisting the Russian invasion. First, Ukraine has mobilized its military. “Ukraine has one of Europe’s largest militaries, with 170,000 active-duty troops, 100,000 reservists and territorial defense forces that include at least 100,000 veterans.”[12] Many citizens have since the beginning of the Russian attack volunteered for these units of territorial defense. The Ukrainian government has begun drafting civilian men between 18 and 60 to join the war effort, forbidding them from leaving the country. In addition, the government has called for international volunteers to join the struggle which is both militarily and politically problematic.[13] In addition, some 500,000 Ukrainians,70 to 80% of them men, have returned to the Ukraine,[14] many of them to fight the Russian invasion.

“On the battlefield, the Ukrainian military is conducting a hugely effective and mobile defense, using their knowledge of their home turf to stymie Russian forces on multiple fronts,” said Gen. Mark A. Milley, the chairman of the U.S. Joint Chiefs of Staff. General Milley said some of the tactics employed by Ukrainian troops included using mobile weapons systems to bedevil the Russians wherever they could. Ukraine’s forces [he said] are “fighting with extraordinary skill and courage against Russian forces.”[15] Using “guerrilla-style tactics” they proved able to hold off much larger and better armed Russian forces for weeks.[16]

A reporter writes, “Ukrainian forces have bogged down Russian units in cities and small towns; street-to-street fighting favors defenders who can use their superior knowledge of the city’s geography to hide and ambush. They attacked isolated and exposed Russian units moving on open roads, which are easy targets. They made repeated raids on poorly protected supply lines in an attempt to deprive the Russians of necessary supplies such as fuel.”[17] Western military officials say, “Hitting and ambushing Russian forces behind the contact lines with fast-moving units, often at night, has proven among its most effective field tactics and is adding to the logistical missteps the Russians still have not been able to overcome, military strategists say. They add that the tactics are also demoralizing Russian troops.”[18]

The Ukrainian army also claims the formation of a unit of Russian deserters fighting in its ranks, the “Freedom Legion of Russia”, with the participation of Belarusian fighters. A statement by a Russian officer was broadcast:

I appeal to the military personnel of the Armed Forces of the Russian Federation, who are currently on the territory of Ukraine. […] I will say only one thing: Russian officers are turning to you. On February 24, we […] entered the territory of independent Ukraine, following the criminal orders of the dictator Putin. I realized that we obviously did not come here with good intentions and that no one was waiting for us here with flowers as if we were liberators, but on the contrary, they cursed us and called us fascists. Military comrades, following the order of the dictator Putin, we have made a terrible mistake. Most of you know this. On February 27 […] my company and I switched to the side of Ukraine in order to really protect the people from the Nazis. […] Join our ranks, become part of the Freedom Legion of Russia. Only together can we save Russia from humiliation and devastation. Only together will we save our people.

We have not been able to verify the existence of this Legion, though there are video interviews and texts on social media, but if true, for us internationalists, it is a masterful lesson in revolutionary politics.[19]

The Russians have had considerable success in taking territory, says Michael Kofman, director of Russian studies at the CNA security think-tank. But, he adds, these advances were not necessarily the sole result of Russian battlefield supremacy. Ukraine, Kofman explains, made the tactical decision to trade “space for time”: to withdraw strategically rather than fight for every inch of Ukrainian land, fighting the Russians on the territory and at the time of their choosing.

As the fighting continued, the nature of the Ukrainian choice became clearer. Instead of getting into pitched large-scale battles with Russians on open terrain, where Russia’s numerical advantages would prove decisive, the Ukrainians instead decided to engage in a series of smaller-scale clashes[20].

This has not been without its costs, Kofman says. Ukrainians have suffered significant losses, too. Russia’s numerical and technological advantages remain and could yet prove decisive, allowing the Russians to besiege Ukraine’s major cities and starve them into submission.[21] Still, the Ukrainian strategy has been effective and British intelligence reported on March 18 that Russia’s offensive had “largely stopped on all fronts.”[22] According to Mason Clark, an expert on the Russian military, “It is unlikely that Russia’s efforts to replace its losses will allow it to successfully resume major operations around Kiev in the near future.”[23]

What is the problem of the Russian army?

Within a few days, it became clear that Russia had both overestimated its own advantages and underestimated its opponent. Zach Beauchamp of Vox wrote,

Once Putin’s strategy failed in the first few days of fighting, the Russian generals had to craft a new one on the fly. What they found – massive artillery bombardments and attempts to encircle and besiege major Ukrainian cities – is more effective (and brutal). But Russia’s initial failures gave Ukraine crucial time to entrench itself and receive external supplies from NATO forces, which strengthened its defenses.[24]

The Russian Army proved unable to adapt to a new situation, was poor at logistics, unable to move its troops and maintain their supplies; it was bad at coordination of air and land forces; and its communications were poor.[25] Some of these problems, such as fuel supplies, may have been the result of the political corruption rife in Russia. Issues such a fuel procurement existed long before the war.[26]

As a result, Russia’s losses have been quite significant. The Ukrainian Armed Forces, which may exaggerate Russian loses, reported a week ago that 16,400 Russian soldiers had been killed since Feb. 24. The UAF also claims that Russia has lost 575 tanks, 1,640 armored vehicles, 1,131 cars, 293 artillery pieces, 91 multiple rocket launchers, 51 surface-to-air missiles, at least 117 jets, 127 helicopters, 7 boats/ships, 73 fuel tankers, and 56 drones.[27] Other sources such as NATO given similar numbers. Ukrainian and Western sources report that an extraordinary seven Russian generals have been killed.[28]

Reporter Zach Beauchamp of Vox writes:

A recent U.S. intelligence assessment states that Russia “lost more than 10 percent of its initial invasion force due to a combination of factors such as battlefield deaths, injuries, capture, illness, and desertion.” “Once they are below 75 percent, their overall effectiveness is likely to collapse,” writes Phillips O’Brien, a professor of strategic studies at the University of St. Andrews. If the Russians don’t send well-trained fresh troops very quickly (and they won’t be mercenaries or impressed people on the streets of Crimea), their entire strategy seems useless.”[29]

Russia, with its overwhelming air superiority, should be winning the air war, but according to Beauchamp, so far it is not.[30]

It is not surprising that in these circumstances morale in the Russian Army would be low, especially given that according to military analysts it was already low before the war began. The Russian army is riddled with divisions, between the contract soldiers and the conscripted soldiers and between the various ethnic groups, and there is also widespread corruption and brutality against the conscripts. It is these conditions that account in part for the army’s failures.[31]

As discussed earlier, a stalemate can be ended if one party can find a new ally. Ukraine has been receiving supplies from the liberal capitalist democracies of NATO while Russia, an authoritarian capitalist regime that many leftwing observers characterize as tending toward fascism, has turned to the kindred Chinese government, but, “China has publicly stated that it will not provide financial or military aid to Russia and has promised additional humanitarian aid to Ukraine, but blamed the United States for the war in Ukraine.”[32]

Russia is also attempting to win the war by increasing the size of its military. According to the Ukrainian Military Intelligence Directorate, Russia is “deploying reserves from the central and eastern military districts.” According to the same source, the conscripts in these regions “are equipped with military equipment dating from the 1970s.” The same source indicates that Russian forces have “an urgent need to repair damaged military equipment” and that “the lack of foreign components slows down production in the main Russian military industries.”[33]

Another ISW article notes that, “Russian forces are unlikely to be able to solve their command-and-control problems in the short term. A senior U.S. defense official said on March 21 that Russian forces are increasingly using unsecured communications due to lack of capability on secure networks.”[34] This means that since their radios or telephones aren’t working, Russian soldiers sometimes use their own phones or phones taken from Ukrainians.

Meanwhile, Russia still seems to have failed to resolve its command-and-control problems. CNN cites several sources as saying that it is unclear whether “Russia has appointed a general commander for the invasion of Ukraine” and that “Russian units in different military districts appear to be fighting over resources and not coordinating their operations.”[35]

Russia has lost thousands of troops, but it cannot rely on its reserves or conscripts. Another Institute of War neocon, Mason Clark, writes:

Russian conscription efforts, which Ukrainian intelligence expects to begin on April 1, are unlikely to provide Russian forces around Ukraine with sufficient combat power to restart major offensive operations in the near term. Russia’s pool of available well-trained replacements remains low and new conscripts will require months to reach even a minimum standard of readiness….The Russian military is likely close to exhausting its available reserves of units capable of deploying to Ukraine.[36]

With no new large sources of fighters, Russia may be forced to give up its offensive campaign.

With his troops stalemated in Ukraine and unable to take most of the cities they had surrounded, Putin decided he would bomb the cities. As of March 28, his planes have bombed some 67 towns and cities apparently to punish Ukraine for frustrating his plans and showing the incompetence of his generals, the stupidity of their strategies, their lack of logistic and communication capability, and the poor quality of their equipment. Putin’s air force has intentionally bombed not only military targets, but also many residential areas, destroying schools and hospitals, homes and apartment buildings forcing ten million–25% of the population from their homes, and over 3.5 million have left the country.[37] Thousands of civilians have been killed. Russia has been accused of war crimes and crimes against humanity for its attack on civilian targets and of using cluster bombs and is now being investigated by the International Criminal Court,[38] though Putin and the Russian Federation (like the United States) don’t recognize its jurisdiction.

So, though the war is at an impasse, the Russian destruction of cities and murder of civilians goes on. We should also note that the Russian Army and the Russian Federal Security Service (FSB – the successor to the KGB) have been kidnapping Ukrainian civilians, and reportedly deporting some of them to Russia. Among the kidnapped are artists,[39] journalists[40], and political figures,[41] as well as children.[42] All of this together, the bombing of cities, the murder and kidnapping of civilians, is what has been called “total war,” an attempt to win the war by completely terrorizing and demoralizing the Ukrainian population. And these are, of course, crimes against humanity.

Still, it is not clear that even inhuman tactics can change the balance in the war.

What is the state of the stalemate at this point? Russia, having destroyed 80 percent of Mariupol, has still not taken control of the city, though it may soon. Frustrated in its ground war Russia has expanded its artillery, missile, and air attacks, bombing several Ukrainian cities. While it says it has turned its forces to the east, to Donbas, it will probably continue to bomb Kyiv. Ukrainian resistance has forced Russia to divert troops and tanks to defend its rear.”[43]

Due largely to the heroism of the Ukrainian resistance, a very smart combination of the twenty-first century version of the “art of war,” modern weaponry that can be used by the so called “techno-guerillas” in the national resistance, and the participation of ordinary people in the war, Ukraine has had an initial success. The stalemate of the Russian army led to a victory in Kyiv. The Russian forces are obliged to withdraw to the East and South of the country. It is a political victory as well as a military one, even if, obviously, the war is not ended and Putin’s Russia can still be victorious.

As we can see, Russian forces are trying to join up to occupy the East of the country nearer Russia. Nevertheless, according to some sources, the Russian forces withdrawn from northeastern Ukraine for “redeployment to eastern Ukraine are heavily damaged.”[44] And if we are to believe the Ukrainian General Staff, the Russian soldiers do not seem very motivated and sometimes disobey orders. Thus, according to this same source, “two tactical groups of battalions” that had very recently been transferred from South Ossetia to Donbass, “refused to fight” and soldiers of the Russian 31st Airborne Brigade reportedly refused the order to resume fighting, “citing excessive losses.”

Every day of resistance is a day of winning, every day is a grain of sand in Putin’s war machine. With each passing day, Putin’s fascistic regime will face increasing internal resistance. With each passing day, we shall see the labor movement rising up against Putin’s war, striking and blocking Russian ships, as the British and Swedish dockers have already been doing. The Ukrainian people in arms and the Russian people under the boot need us internationalists to build a powerful resistance movement in all countries against Russia’s war on Ukraine, a movement that in its own independent role contributes to the defeat of Russian imperialism, the end of the war and the defense of a free and democratic Ukraine.

To make a provisional conclusion, let’s quote Gilbert Achcar:

Supporting Ukraine’s position in negotiations about its own national territory requires a support to its resistance and its right to acquire the weapons that are necessary for its defense from whichever source possesses such weapons and is willing to provide them. Refusing Ukraine’s right to acquire such weapons is basically a call for it to capitulate. In the face of an overwhelmingly armed and most brutal invader, this is actually defeatism on the wrong side, amounting virtually to support for the invader.[45]

NOTES

[1] Andrew E. Kramer and Neil MacFarquhar, “Russia in Broad Retreat From Kyiv, Seeking to Regroup From Battering,” New York Times, April 2, 2022, at: https://www.nytimes.com/2022/04/02/world/europe/ukraine-russia-kyiv.html

[2] Victoria Kim, “What is the Wagner Group,” New York Times, March 31, 2022, at: https://www.nytimes.com/2022/03/31/world/europe/wagner-group-russia-ukraine.html

[3] “Russia’s Wagner Group withdraws fighters in Libya to fight in Ukraine,” Memo Middle East Monitor, March 26, 2022, at: https://www.middleeastmonitor.com/20220326-russias-wagner-group-withdraws-fighters-in-libya-to-fight-in-ukraine/

[4] “Ukraine: Apparent War Crimes in Russia-Controlled Areas,” Human Rights Watch, April 3, at: https://www.hrw.org/news/2022/04/03/ukraine-apparent-war-crimes-russia-controlled-areas and Carlotta Gall, Andrew E. Kramer and Natalie Kitroeff, “Reports of atrocities emerge from Ukraine as Russia repositions its forces,” New York Times, April 4, 2022,https://www.nytimes.com/live/2022/04/03/world/ukraine-russia-war

[5] Stephanie Nebehay, “United Nations names experts to probe possible Ukraine war crimes,” Reuters, March 30, 2022, at: https://www.reuters.com/world/europe/un-names-experts-probe-possible-war-crimes-ukraine-2022-03-30/

[6] “Images of Russian Atrocities Push West Toward Tougher Sanctions,” New York Times, April 2, 2022 at: https://www.nytimes.com/2022/04/04/world/europe/biden-putin-ukraine-war.html

[7] Jacqui Heinrich and Adam Sabes, “Gen. Milley says Kyiv could fall within 72 hours if Russia decides to invade Ukraine: sources,” FoxNews, Feb. 5, 2022.

[8] See too my earlier article, Patrick Silberstein, “The Russian army is a paper tiger and the paper is now on fire,” available at: https://www.syllepse.net/syllepse_images/articles/liberte—et-de–mocratie-pour-les-peuples-dukraine-2.pdf

[9] Frederick W. Kagan, “What Stalemate Means in Ukraine and Why It Matters, Mar 22, 2022, Institute of War Press, at:

https://www.understandingwar.org/backgrounder/what-stalemate-means-ukraine-and-why-it-matters

[10] Frederick W. Kagan, “What Stalemate Means in Ukraine and Why It Matters, Mar 22, 2022, Institute of War Press, at:

https://www.understandingwar.org/backgrounder/what-stalemate-means-ukraine-and-why-it-matters

[11] Frederick W. Kagan, “What Stalemate Means in Ukraine and Why It Matters, Mar 22, 2022, Institute of War Press, at:

https://www.understandingwar.org/backgrounder/what-stalemate-means-ukraine-and-why-it-matters

[12] Eric Schmitt, Helene Cooper and Julian E. Barnes, “How Ukraine’s Military Has Resisted Russia So Far,” New York Times, Mar. 3,2022, at: https://www.nytimes.com/2022/03/03/us/politics/russia-ukraine-military.html

[13] Anthony Hitchens, “Among Ukraine’s Foreign Fighters,” New York Review of Books, March 26, 2022, at: https://www.nybooks.com/daily/2022/03/26/among-ukraines-foreign-fighters/

[14] Oscar Kramar, “В Україну після початку вторгнення повернулися вже пів мільйона людей, більшість — чоловіки,” at: https://hromadske.ua/posts/v-ukrayinu-pislya-pochatku-vtorgnennya-povernulisya-vzhe-piv-miljona-lyudej-bilshist-choloviki,” Hromadske, March 22, 2022

[15] Eric Schmitt, Helene Cooper and Julian E. Barnes, “How Ukraine’s Military Has Resisted Russia So Far,” New York Times, Mar. 3,2022, at: https://www.nytimes.com/2022/03/03/us/politics/russia-ukraine-military.html

[16] “Clever Tactics By Ukrainian Forces Stymie Russian Military Despite Power Imbalance,” MSNBC, Mar 16, 2022, at: https://youtu.be/9saWmdjpNmE

[17] Zack Beauchamp, “Is Russia Losing?” Vox, March 18, 2022, at: https://www.vox.com/2022/3/18/22977801/russia-ukraine-war-losing-map-kyiv-kharkiv-odessa-week-three

[18] Jamie Dettmer, “Ukraine Tactics Disrupt Russian Invasion, Western Officials Say,” Voice of America, March 25, 2022, at; https://www.voanews.com/a/ukraine-tactics-disrupt-russian-invasion-western-officials-say-/6501513.html

[19] See Reddit discussion: https://www.reddit.com/r/ukraine/comments/tqg4cz/commander_of_legion_freedom_of_russia_to_putin/ and also on YouTube: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UgRBGLq1D5Y and an article: Natasha Kumar, “ “ The Legion ‘Freedom of Russia’ was created in the Armed Forces of Ukraine: prisoners who decided to fight the Putin regime are fighting in it,” The Times Hub, March 30, 2022, at: https://thetimeshub.in/the-legion-freedom-of-russia-was-created-in-the-armed-forces-of-ukraine-prisoners-who-decided-to-fight-the-putin-regime-are-fighting-in-it

[20] Zack Beauchamp, “Is Russia Losing?” Vox, March 18, 2022, at: https://www.vox.com/2022/3/18/22977801/russia-ukraine-war-losing-map-kyiv-kharkiv-odessa-week-three

[21] Zack Beauchamp, “Is Russia Losing?” Vox, March 18, 2022, at: https://www.vox.com/2022/3/18/22977801/russia-ukraine-war-losing-map-kyiv-kharkiv-odessa-week-three

[22] Putin has made some gross misjudgments – NRK Urix – Foreign news and documentaries,” World Today News, March 18, 2022, at: https://www.world-today-news.com/putin-has-made-some-gross-misjudgments-nrk-urix-foreign-news-and-documentaries/

[23] Mason Clark, “Russian Offensive Campaign Assessment,” Institute for the Study of War, March 27, 2022, at:

[24] Zack Beauchamp, “Is Russia Losing?” Vox, March 18, 2022, at: https://www.vox.com/2022/3/18/22977801/russia-ukraine-war-losing-map-kyiv-kharkiv-odessa-week-three

[25] Zack Beauchamp, “Is Russia Losing?” Vox, March 18, 2022, at: https://www.vox.com/2022/3/18/22977801/russia-ukraine-war-losing-map-kyiv-kharkiv-odessa-week-three

[26] Zack Beauchamp, “Is Russia Losing?” Vox, March 18, 2022, at: https://www.vox.com/2022/3/18/22977801/russia-ukraine-war-losing-map-kyiv-kharkiv-odessa-week-three

[27] Kyiv Independent newspaper, March 27, 2022.

[28] “Russian generals are getting killed at an extraordinary rate,” Washington Post, March 26, 2022.

[29] Zack Beauchamp, “Is Russia Losing?” Vox, March 18, 2022, at: https://www.vox.com/2022/3/18/22977801/russia-ukraine-war-losing-map-kyiv-kharkiv-odessa-week-three

[30] Zack Beauchamp, “Is Russia Losing?” Vox, March 18, 2022, at: https://www.vox.com/2022/3/18/22977801/russia-ukraine-war-losing-map-kyiv-kharkiv-odessa-week-three

[31] Zack Beauchamp, “Is Russia Losing?” Vox, March 18, 2022, at: https://www.vox.com/2022/3/18/22977801/russia-ukraine-war-losing-map-kyiv-kharkiv-odessa-week-three

[32] Institute for the Study of War (ISW), March 21.

[33] ISW, March 21.

[34] Frederick W. Kagan, George Barros, and Kateryna Stepanenko, ISW, March 22, 2022.

[35] “U.S. Unable to Identify Russian Field Commander in Ukraine,” at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?app=desktop&v=NXm_3CktFtQ

[36] Mason Clark and George Barros, Russian Offensive Campaign Assessment,” Institute for the Study of War, March 28, 2022, at: https://www.understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign-assessment-march-28.

[37] Keith Collins, Danielle Ivory, Jon Huang, Cierra S. Queen, Lauryn Higgins, Jess Ruderman, Kristin White and Bonnie G. Wong, “Russia’s Attacks on Civilian Targets Have Obliterated Everyday Life in Ukraine,” The New York Time, March 23, 2022, at: https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2022/03/23/world/europe/ukraine-civilian-attacks.html

[38] Aubrey Allegretti, “ICC launches war crimes investigation over Russian invasion of Ukraine,” Guardian, March 3, 2022, at: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2022/mar/03/icc-launches-war-crimes-investigation-russia-invasion-ukraine

[39] CGT-Spectacle, “We Demand the Immediate Release of Ukrainian Political Prisoners Abducted by the Russian Army,” New Politics, March 24, 2022, at: https://newpol.org/ukraine-demand-the-immediate-release-of-political-prisoners-abducted-by-the-russian-army/

[40] Rachel Treisman, “Russian forces are reportedly holding Ukrainian journalists hostage,” NPR, March 25, 2022, at: https://www.npr.org/2022/03/25/1088808627/ukrainian-journalists-missing-detained

[41] Matt Murphy and Robert Greenall, “Ukraine War: Civilians abducted as Russia tries to assert control,” BBC News, March 26, 2022, at: https://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-60858363

[42] Rebecca Cohen, “US Embassy accuses Russia of kidnapping children amid reports it’s deporting thousands of Ukrainians by force,” Business Insider, March 22, 2022, at: https://www.businessinsider.com/us-embassy-accuses-russia-of-kidnapping-ukrainian-children-2022-3 We have also heard reports of Russians taking children from Ukrainians speaking in meetings.

[43] ISW March 23, 2022, at: https://www.understandingwar.org/backgrounder/ukraine-conflict-updates

[44] Mason Clark, George Barros, and Karolina Hird, “Russian Offensive Campaign Assessment,” Institute for the Study of War, April 2, 2022, at: https://www.understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign-assessment-april-2

[45] Gilbert Achcar. “Coherence and Incoherence about the War in Ukraine,” New Politics, April 4, 2022, at; https://newpol.org/coherence-and-incoherence-about-the-war-in-ukraine/

In a recent statement released by Hugpong ng Pagbabago (HNP or Alliance for Change), the regional party founded by Sara Duterte, daughter of Philippine President Rodrigo Duterte, activist-scholar Professor Walden Bello was unfoundedly and maliciously labeled as a “narco-politician.”

In a recent statement released by Hugpong ng Pagbabago (HNP or Alliance for Change), the regional party founded by Sara Duterte, daughter of Philippine President Rodrigo Duterte, activist-scholar Professor Walden Bello was unfoundedly and maliciously labeled as a “narco-politician.”

Let us imagine that the United States invaded Venezuela, as it contemplated doing for a while under Donald Trump, and that Russia decided to supply the Venezuelan government of Nicolás Maduro with weapons to help it fight the invaders. US troops are meeting a fierce resistance in the barrios and countryside of Venezuela. Negotiations between Washington and Caracas have started in Colombia, while Washington is trying to force the Venezuelan government to capitulate to its diktat.

Let us imagine that the United States invaded Venezuela, as it contemplated doing for a while under Donald Trump, and that Russia decided to supply the Venezuelan government of Nicolás Maduro with weapons to help it fight the invaders. US troops are meeting a fierce resistance in the barrios and countryside of Venezuela. Negotiations between Washington and Caracas have started in Colombia, while Washington is trying to force the Venezuelan government to capitulate to its diktat.

Dear compatriots, dear workers!

Dear compatriots, dear workers!

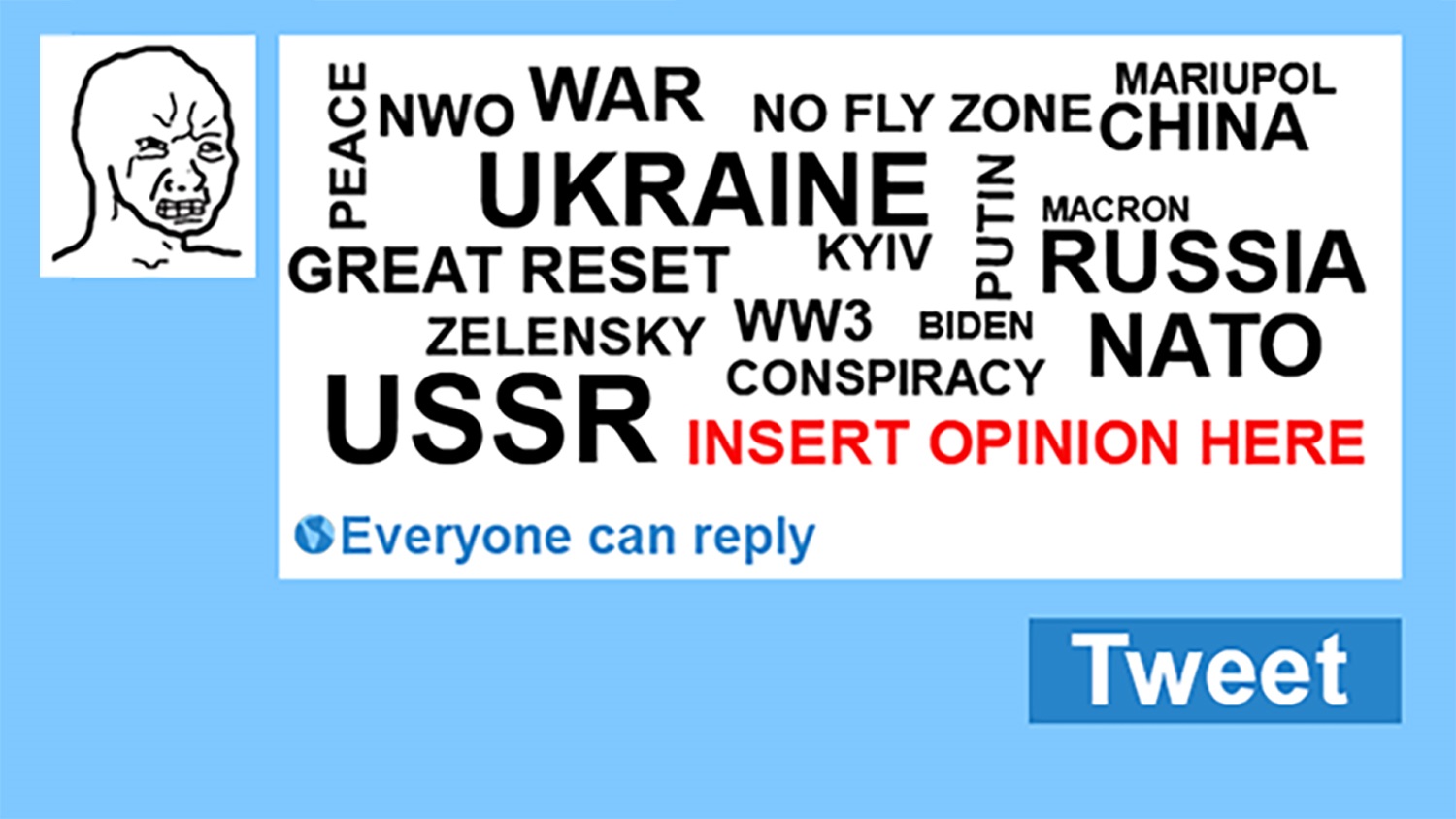

In the postwar period, the German philosopher and critic Theodor Adorno famously condemned directly political artworks, stating “To write poetry after Auschwitz is barbaric.” Today we might well ask whether it’s possible for onlookers to create memes about the war in Ukraine. Too often even our most sincere statements of solidarity expressed on social media seem crass, not unlike gestures made by outlets, such as the renaming of the cocktail “Moscow Mule” to “Kyiv Mule.” What can Adorno teach us about representations of warfare in the social media age?

In the postwar period, the German philosopher and critic Theodor Adorno famously condemned directly political artworks, stating “To write poetry after Auschwitz is barbaric.” Today we might well ask whether it’s possible for onlookers to create memes about the war in Ukraine. Too often even our most sincere statements of solidarity expressed on social media seem crass, not unlike gestures made by outlets, such as the renaming of the cocktail “Moscow Mule” to “Kyiv Mule.” What can Adorno teach us about representations of warfare in the social media age?

Recently, the Ukrainian National Defense and Security Council decided for the temporary suspension of the activities of a number of Ukrainian political parties. The list includes both major opposition parties and less known ones that use words ‘progressive,’ ‘left,’ or ‘socialist’ in their names. President of Ukraine Volodymyr Zelensky accused them of “connections with Russia,” but did not back the claim with any proper legal reasoning.

Recently, the Ukrainian National Defense and Security Council decided for the temporary suspension of the activities of a number of Ukrainian political parties. The list includes both major opposition parties and less known ones that use words ‘progressive,’ ‘left,’ or ‘socialist’ in their names. President of Ukraine Volodymyr Zelensky accused them of “connections with Russia,” but did not back the claim with any proper legal reasoning.

The Ukrainian government announces the abduction in the occupied city of Kherson of the director of the regional theater and director Oleksandr Kniga by the Russian army. Putin is implementing his unfortunately usual policy of terror and intimidation of the populations in the occupied territories, especially those who can speak out against the occupation.

The Ukrainian government announces the abduction in the occupied city of Kherson of the director of the regional theater and director Oleksandr Kniga by the Russian army. Putin is implementing his unfortunately usual policy of terror and intimidation of the populations in the occupied territories, especially those who can speak out against the occupation.

The following are six questions related to the position stated in my “Memorandum on the radical anti-imperialist position regarding the war in Ukraine”

The following are six questions related to the position stated in my “Memorandum on the radical anti-imperialist position regarding the war in Ukraine”

On March 10, 2022, The Guardian published an article titled “The west v Russia: why the global south isn’t taking sides,” by David Adler, the general coordinator of the Progressive International. In essence, the author of the text tries to justify the position of that part of the Western Left which refused to support the resistance of the people of Ukraine against Putin’s aggression and limited itself to general calls for peace and a “diplomatic solution.” I decided to write a response to this article for several reasons. First, its main argument may seem convincing to many leftists, whereas I disagree with it; second, our Commons Journal is still a member of the Progressive International; and third, the author directly refers to my “

On March 10, 2022, The Guardian published an article titled “The west v Russia: why the global south isn’t taking sides,” by David Adler, the general coordinator of the Progressive International. In essence, the author of the text tries to justify the position of that part of the Western Left which refused to support the resistance of the people of Ukraine against Putin’s aggression and limited itself to general calls for peace and a “diplomatic solution.” I decided to write a response to this article for several reasons. First, its main argument may seem convincing to many leftists, whereas I disagree with it; second, our Commons Journal is still a member of the Progressive International; and third, the author directly refers to my “

Oksana Dutchak is a researcher based in Ukraine and an activist of E.A.S.T. – Essential Autonomous Struggles Transnational. She tells about the current ever-changing situation in Ukraine and local attempts of self-organization to cope with the war. The question of how to create a

Oksana Dutchak is a researcher based in Ukraine and an activist of E.A.S.T. – Essential Autonomous Struggles Transnational. She tells about the current ever-changing situation in Ukraine and local attempts of self-organization to cope with the war. The question of how to create a

We, the undersigned organizations, stand in solidarity with the people of Ukraine, but particularly Ukrainian journalists who now find themselves at the frontlines of a large-scale European war.

We, the undersigned organizations, stand in solidarity with the people of Ukraine, but particularly Ukrainian journalists who now find themselves at the frontlines of a large-scale European war.