An exclusive excerpt from A People's History of Detroit.

[Introduction by Mark Jay and Philip Conklin] In 1965, the correctional population in the U.S., including all those in jail or prison, or on probation or parole, was less than 800,000. At present, the number is around seven million. As a result of this historically unprecedented rise—commonly known as “mass incarceration”—approximately one-third of U.S. adults, disproportionately African Americans and Latinos, have some kind of criminal record.

[Introduction by Mark Jay and Philip Conklin] In 1965, the correctional population in the U.S., including all those in jail or prison, or on probation or parole, was less than 800,000. At present, the number is around seven million. As a result of this historically unprecedented rise—commonly known as “mass incarceration”—approximately one-third of U.S. adults, disproportionately African Americans and Latinos, have some kind of criminal record.

For years the origins of mass incarceration have been a subject of heated debate, both within academia and within the American left more broadly. The terms of this debate were largely set by Michelle Alexander’s 2010 work The New Jim Crow, which presents the carceral boom as a “racial caste system” installed by white elites to control people of color and reverse the gains of the civil rights movement. In recent years, however, Alexander’s “racial backlash” thesis has been increasingly challenged by an array of scholars and activists who have emphasized aspects of mass incarceration that Alexander downplayed, including the economic context for the punitive turn, African Americans’ support for harsh anti-crime laws, and the extent to which mass incarceration has targeted poor people of all races. This debate has mapped onto the often hostile “class vs. race” debate that continues to divide and animate the U.S. left.

The following excerpt—which gives an in depth political-economic analysis of Detroit from the late 1960s to early 1970s, when Detroit elected its first black mayor, Coleman Young—can be seen as an intervention into this debate. Our book, A People’s History of Detroit, analyzes the past century of the city’s history from a Marxist perspective. What this history reveals is a struggle between capitalists on the one hand, seeking to make the city a profitable place to invest, and workers, vying to build a city that would meet the basic needs of its residents, on the other. This particular period was a crucial point in this struggle, as these groups jostled over the fate of the city in the wake of the Great Rebellion of 1967, at the time the largest and bloodiest civil uprising since the Civil War. It was out of this paroxysm that two radical groups in Detroit formed: the League of Revolutionary Black Workers and the Detroit chapter of the Black Panther Party. It is in the context of the repression of groups like these, we argue, that mass incarceration must be understood. While the LRBW and the BPP challenged the hegemony of capitalism in the city, elites sought to resolve the crisis through corporate investment and aggressive policing. Simply put, locking up underemployed workers in the wake of deindustrialization served the double purpose of containing the political threat posed by these workers, and of obfuscating the political-economic causes of social unrest by refracting it through the prism of “crime.” While this process was thoroughly racialized, to reduce the issue to racial animus on the part of Detroit’s white residents and leaders is to paper over the complexities of the problem. This period was also a time when black politicians were increasingly taking over the administrations of major U.S. cities, and despite their desire to redress racial inequalities, black urban regimes tended to support and even intensify anti-crime measures as a solution to the growing “urban crisis.” Indeed, in 1974 Detroit’s first black mayor, Coleman Young, launched his own “war on crime,” with the support of civil rights activists across the city.

It is worth reflecting on this history, especially as the “war on crime” that Young launched nearly fifty years ago continues to this day (it is now led by a black police chief, James Craig). Even as the city experiences a so-called “revitalization,” Detroit elites continue to regard poverty, unemployment, and political protest primarily as security issues, to be dealt with by increasingly militarized private and public police forces. And while there were, and still are, many racist politicians and police officers, mass incarceration is more than a racial problem: simply put, criminalization is a cheap way of managing poverty. Unfortunately, policing the poor has proven more politically expedient than taxing the rich and using the money to fund broad poverty-alleviating social programs. As Detroit activist James Boggs suggested more than a half-century ago, the problem is not only the money-hungry capitalists and corrupt politicians, but also all those people who “resent the continued cost to them of maintaining these expendables but who are determined to maintain the system that creates and multiplies the number of expendables.”

***

Controlling “Revolutionary Attitudes”

I met Marx, Lenin, Trotsky, Engels, and Mao when I entered prison and they redeemed me. For the first four years, I studied nothing but economics and military ideas. I met black guerrillas, George “Big Jake” Lewis, and James Carr, W. L. Nolen, Bill Christmas, Torry Gibson, and many, many others. We attempted to transform the black criminal mentality into a black revolutionary mentality. As a result, each of us has been subjected to years of the most vicious reactionary violence by the state. Our mortality rate is almost what you would expect to find in a history of Dachau. —GEORGE JACKSON, Soledad Brother, 1970

During the late 1960s and early 1970s, as governments violently cracked down on radical movements throughout the United States, the rate at which new inmates were thrown into prison increased more rapidly than at any time in the twentieth century, eclipsing even the rate during the penal crisis of the Great Depression.117 Loïc Wacquant, a prominent sociologist at UC Berkeley, expressed a common myth when he wrote that the prison boom that has occurred in the United States in the past fifty years was “contrary to all expectations.” In fact, as the state accelerated its violent crackdown of radical organizations, many within these organizations foresaw the imminence of mass incarceration. At the same time that the French philosopher Michel Foucault, in his widely celebrated Discipline and Punish, wrote that the “widespread, badly integrated confinement of the classical age” was coming to an end and that “the specificity of the role of the prison and its role as link are losing something of their purpose,” Black Panther leader Assata Shakur accurately predicted the exact opposite: “In the next five years, something like three hundred prisons are in the planning stages. This government has the intention of throwing more and more people in prison.”118

As underemployed blacks were thrown in prison en masse, leaders like George Jackson of the BPP organized prisoners as part of the Panthers’ general strategy of turning the lumpenproletariat into a revolutionary force. The number of prison uprisings increased from five in 1968 to forty-eight in 1971.119 Jackson wrote at the time, “Only the prison movement has shown any promise of cutting across the ideological, racial and cultural barricades that have blocked the natural coalition of left-wing forces at all times in the past.” Indeed although the majority of rebelling prisoners were black, Jackson insisted on the uprisings’ socialist character: “If a man wants to relate to my blackness, fine, but I would prefer he relate to me on the basis of my status as a soldier in the world revolution.”120 The state’s response to the increasing number of prisoner uprisings was to turn prisons into sites of “low-intensity warfare.”121

The most famous uprising was in Attica, the maximum-security prison in New York where the most recalcitrant prisoners were sent. On September 19, 1971, a couple weeks after Jackson had been assassinated in San Quentin Prison, 1,300 prisoners took control of Attica. On national television, the prisoners made demands such as “adequate food, water, and shelter,” “effective drug treatment,” an “inmate education system,” and “amnesty from physical, mental, and legal reprisals.” In response, Governor Nelson Rockefeller ordered police and National Guardsmen to quash the uprising, which they did, but only after killing twenty-nine prisoners and ten of the guards who had been taken hostage.122

The national media initially blamed the deaths on the Attica rebels. The New York Times suggested that “the deaths of these persons by knives . . . reflect a barbarism wholly alien to civilized society. Prisoners slashed the throats of utterly helpless unarmed guards.”123 But days later an autopsy revealed that the prisoners had not killed a single person; the raiding officers had killed all thirty-nine men.124

Soon after the uprising, Rockefeller allocated $4 million to Attica to enhance the security apparatuses at the prison and search out new sites for a “maxi-maxi prison” to place militant prisoners.125 The narrative was clear: Attica had not been a political uprising but a riot by lawless criminals and communist agitators. As Dan Berger has shown, this narrative legitimated the state’s authoritarian response: this is when supermax prisons were built to lock up the country’s most recalcitrant prisoners, keeping them in solitary confinement for twenty-two to twenty-three hours a day.126

As the prison warden of Marion, the nation’s first supermax prison, explained in 1973, “The purpose of the Marion control unit is to control revolutionary attitudes in the prison system and in society at large.”127 In the mid1960s Marion was the only supermax prison in the country; by 1997 there were more than fifty-five.128 The Marion model of “indefinite lockdown and limited access to the outside, brutal segregation and random attacks . . . has become the dominant model of prison in America.”129

In these supermax prisons, which cost between $30 million and 75 million to construct, “physical contact is limited to being touched through security doors by correctional officers while being put in restraints or having restraints removed. Most verbal communication occurs through intercom systems.”130 These prisons offer “virtually no educational” programs, and the books available for reading are extremely limited. Supermaxes are set up so that never again will a prisoner like George Jackson have the chance to be “redeemed” by revolutionary literature.131 Had he served his prison sentence in a supermax, Malcolm X would surely not have been a member of a prison debate team that beat MIT’s debate team.132

Law and Order

In Detroit and around this country, the authoritarian response inside prisons paralleled an authoritarian response outside. Police funding offers one barometer of this process: between 1962 and 1977 local government spending on police increased from around $2 billion to $9 billion. In 1970 there was one paramilitary police unit in the United States; five years later there were five hundred, and Detroit and most major cities had their own paramilitary unit.133 To understand this shift, let us take a closer look at the way political elites managed and mythologized social turmoil in the late 1960s.

As Marxist criminologists Morton Wenger and Thomas Bonomo observe, “The loss of confidence in the ability of a particular form of the capitalist state to handle its own social contradictions can as easily lead to a shift of allegiance by the socially insecure masses to a more proactive and brutal capitalist regime.”134 This is precisely what happened in the late 1960s. Richard Nixon won the 1968 presidential election with an appeal that included the claim that the “crime problem” would be solved “not [by] quadrupling the funds for ‘any governmental war on poverty,’ but convicting more criminals.” The counterrevolution that James Boggs had predicted just a few years earlier was taking shape. The liberal War on Poverty had already demonstrated that it was unable to restore corporate profitability and quell widespread dissent—and so the War on Crime was ratcheted up.135

In Detroit, liberal elites were under attack for their inability to restore law and order. Predating the contemporary “New Detroit” revitalization efforts by almost fifty years, in the wake of the Rebellion, liberal elites had assembled the New Detroit Committee (NDC), a coalition of union higher-ups, community leaders, political elites, members of the black middle class, and corporate CEOs. The NDC, the “backbone of any liberal attempt to improve conditions in the Motor City and regain political legitimacy after 1967,” sought to quell the city’s tensions via urban renewal and racial redistribution, promising to invest millions in downtown development and community programs. As Judge Crockett recalls, NDC’s primary concern was “to sort of quiet things down” after the Rebellion.136 The historian and Detroit native Heather Ann Thompson writes that, at the outset, the NDC operated under the assumption that “black militants were relatively minor figures” who “posed a long-term threat” only if civil rights issues continued to be ignored by the state.137 The NDC therefore was prepared to “listen to, and even to fund, black radicals.” New Deal funding was thus channeled to radical programs that included the Community Patrol Corps, which emulated the Black Panthers’ famous police patrols. Teens in “all-black uniforms” patrolled the city and monitored instances of police brutality.138 By supporting such programs, liberals signaled their attempts to fund, and thereby politically integrate and co-opt, local dissidents.139 This incorporation strategy didn’t always work, as, for example, when Detroit’s Federation for Self-Determination, an organization made up of local activists such as Cockrel, Grace Lee Boggs, and Reverend Cleage, turned down a $100,000 NDC grant which stipulated that the money was not to be used for “political” purposes. Rejecting the money, Cleage said, “We will not accept white supervision and control.”140

Whereas activists complained that NDC proposals were both inadequate and mostly about co-optation, many conservative elites feared that NDC’s contacts with local militants would facilitate a revolution. Heather Ann Thompson points out that in the span of a couple of years, “‘marginal’ black radicals had managed to take over the media of key liberal institutions such as Wayne State University, and were encouraging black students to take over the very schools that liberal School Board members were trying to integrate. Worse yet, black radicals had joined with whites in the call for an all-out urban revolution.”141

In 1969 Wayne County Sheriff Roman Gribbs stepped in to mediate this situation with an iron fist. Gribbs was elected mayor of Detroit having run a campaign that centered on the promise to end liberal permissiveness, create an elite police unit to deal with civil disturbances, and wage an “all-out fight against crime in the streets.”142

As we have seen, the crime panic of the late 1960s did have important roots in reality—the reality of increasing crime rates. Nationally, reported street crime quadrupled between 1959 and 1971, and rates of violent crime and homicide doubled between the early 1960s and early 1970s.143 Detroit’s population decreased by 300,000 between 1950 and 1970; during these years the white population nearly halved, while the black population more than doubled. (These two racial groups made up 98 percent of Detroit’s population in 1970.)144 In 1970, the year that Gribbs took office, there were more than twenty-three thousand reported robberies. The city’s homicide rate more than tripled between 1960 and 1970.145 As many as two-thirds of these murders were linked to the drug trade.146 This was the time of a devastating heroin epidemic, one with roots in the Vietnam War: 30 percent of U.S. soldiers used heroin during their time in Vietnam, and heroin was imported into the country at cheap rates during and after the war.147 “One journalist cited as many as fifty thousand heroin addicts on [Detroit’s] streets, spending over a million dollars a day to feed their habits.”148 By the time Gribbs took office “an army of drug addicts lived in the remains of 15,000 inner-city houses abandoned for an urban renewal project which never materialized.”149

When one considers the problems of deindustrialization, along with Detroit’s dramatic demographic shifts, racial tensions, and widespread unemployment, the rising crime rate is a tragic and foreseeable outcome.150 Liberal critics of mass incarceration tend to obscure the reality of crime, arguing that rising crime rates were an invention white elites used to justify a regressive program of racial discrimination. There is truth to these sentiments, as racial disparities in the criminal justice system more than attest to. To deny the reality of violent crime, however, shifts the focus away from the political-economic causes of crime like deindustrialization and the gutting of the welfare state, issues that also disproportionately affect minority populations. Such interpretive moves make invisible the support of poor people and minorities for anticrime measures, as, for example, the black activists in New York City who campaigned for Governor Rockefeller’s draconian drug laws in the late 1960s.151

Both the League of Revolutionary Black Workers and the Black Panthers developed alternative strategies to explain and combat the country’s crime issue. While League leaders acknowledged that crime and heroin addiction were real problems, they viewed the country’s moral panic as an elite-driven strategy to obfuscate the class struggle. As Watson says in Finally Got the News:

There’s a lot of confusion amongst white people in this country, amongst white workers in this country, about who the enemy is. The same contradictions of overproduction . . . are prevalent within the white working class, but because of the immense resources of propaganda, publicity . . . white people tend to get a little bit confused about who the enemy is. You take a look at white workers in Flint for instance, in the automobile industry, who are pretty hard pressed because the Buick plant up there is whipping their ass. . . . But who do they think the enemy is? . . . Crime on the streets is the problem.

BPP founder Huey Newton said that most criminals were simply “illegitimate capitalists”; like Watson, he understood that although white workers and black workers occupied similar “objective” positions in the economic structure, the racialized, law-and-order narrative of urban crisis made it so that white workers would “feel more and more that it’s a race contradiction rather than a class contradiction.” The Panthers’ “survival programs” sought to address the roots of crime and immiseration by providing impoverished residents with food, shelter, health care, and political education.152

When police harassment made sales of the Black Panther a less tenable source of income, Panthers began robbing Detroit’s drug houses, both to earn money and as an attempt to address the interrelated problems of drugs and violent crime. BPP member Ahmad Rahman recalls, “Drug-related crime began to wreak havoc in Black neighborhoods nationwide, diluting calls for community control as citizens turned to the police for relief. Many black people began to shift to the political ‘right.’ . . . Calls for community control of police, became calls for the police—and more prisons.”153

After a botched raid on a “drug den” that resulted in one death, Rahman was captured by police.

When his case went to trial Rahman discovered that the Panther Party superior he and the other young comrades took orders from was an FBI informant and the dope house break-in was part of a COINTELPRO designed to capture “the four most active and productive Panthers in the area—Rahman and his three co-defendants.” Rahman, who was nowhere near the murder when it occurred, pled not guilty. The other three pled guilty [and] were found guilty of felony murder. The shooter in the case served only 12 years and was set free, but for Rahman, who fought to prove his innocence, it would be more than two decades before Gov. John Engler commuted his sentence.154

There are two points worth stressing here. First, it was only after radical working-class groups like the Panthers and the League were brought down that the punitive strategy of mass incarceration could be implemented in poor neighborhoods without meeting violent resistance. The second, related point, is that the war on crime was actually part and parcel of the repression of these radical groups (the very groups that were attempting to combat the causes of crime). During these years crime operated as a signifier that demonized political resistance and collapsed the social causes of the urban crisis into an individualized, moral problem—a perfect example of the process of mythologization. Law and order, rather than progressive social change, could then “resolve” the crisis.155

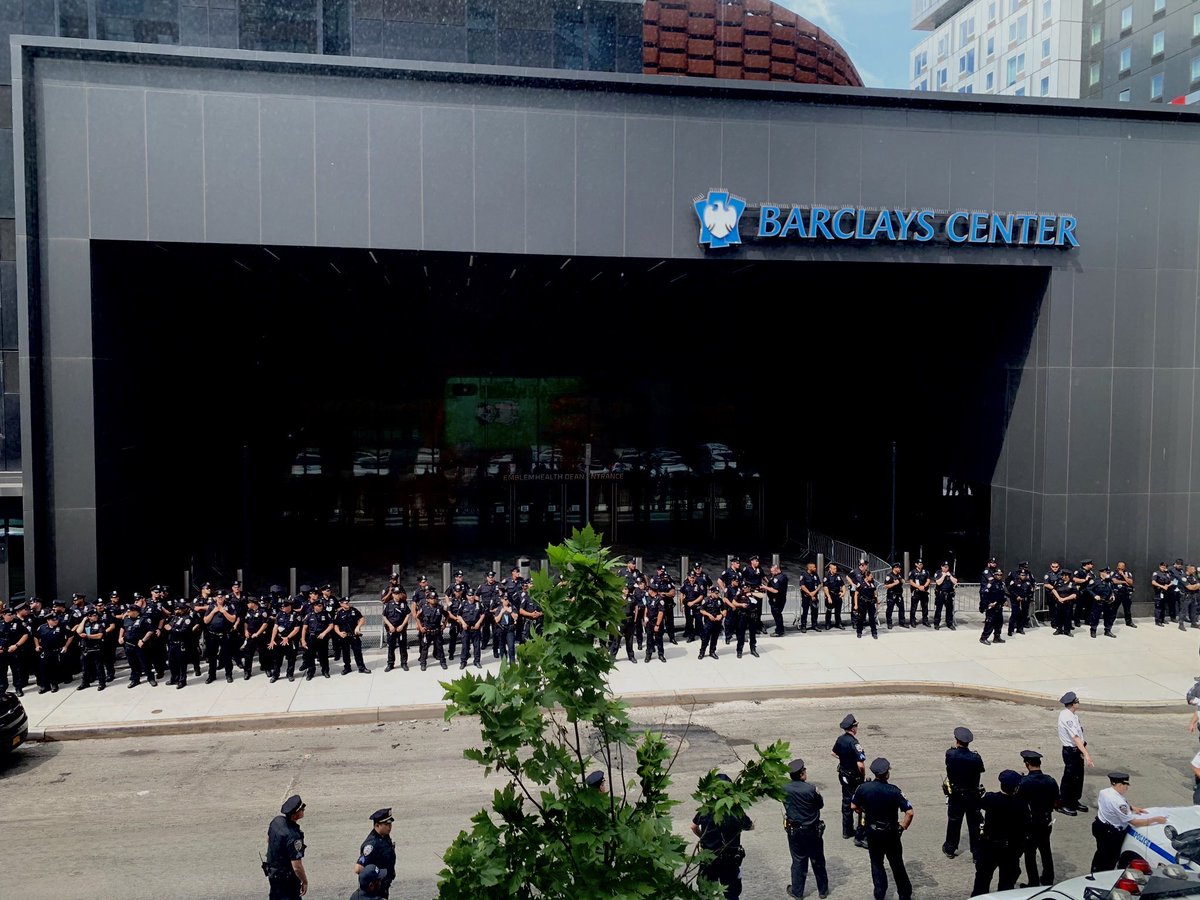

As already mentioned the Kerner Report called for more “training, planning, adequate intelligence systems, and knowledge of the ghetto community.”156 The Omnibus Crime Control and Safe Streets Act of 1968 dedicated $1 billion per year to bolstering U.S. police forces with “computers, helicopters, body armor, military-grade weapons, swat teams, shoulder radios, and paramilitary training.”157 Many of the strategies that police adopted to control working-class militancy at home had their precedents in counterinsurgency tactics used by U.S. forces to quell communist movements abroad. During the Cold War, the Office of Public Safety had worked closely with the cia to train police in South Vietnam, Iran, Uruguay, Argentina, and Brazil. As scholar-activist Alex Vitale writes, upon their return to the United States, imperial officers “moved into law enforcement, including the Drug Enforcement Agency (DEA), FBI, and numerous local and state police forces.” The director of the Office of Public Safety, Byron Engle, testified before the Kerner Commission, “In working with the police in various countries we have acquired a great deal of experience in dealing with violence ranging from demonstrations and riots to guerilla warfare.”158

By January 1971 the new, highly militarized police unit that Gribbs promised was instituted; it was called Stop the Robberies, Enjoy Safe Streets (STRESS). STRESS was a local—and particularly brutal—iteration of a national trend to bolster police departments against the threat of “guerilla warfare.”159 According to the Detroit News article unveiling the program, in a tactic borrowed from police in New York City and the Bay Area, “decoy units” would be sent undercover in “high-crime” areas to play-act as vulnerable citizens, resembling

old women, old men, businessmen, grocery clerks and gas station attendants. . . . They will be prime bait for robbers who prey on such people. And they will be armed and ready. . . . The disguised men will work in teams so that the one being used as a decoy will never be out of sight of one or more of his buddies. . . . “We are going to look like people who live and work in Detroit,” said [District Inspector] Smith. “We are going to make ourselves the victims of crime, rather than other members of the community.”160

In 1971 police murdered an unarmed black Detroiter named Clarence Manning Jr. As part of a decoy operation, a STRESS officer disguised as an intoxicated hippie had provoked Manning, and when Manning approached him, several STRESS officers jumped out of their hiding spots and killed him.161 This murderous behavior was all too common. Within six months of its unveiling, STRESS, which was composed of one hundred officers, most of them white, made forty-six arrests daily using this entrapment technique. In this period, STRESS fatally shot fifteen citizens, thirteen of them black.162 These STRESS killings were the primary reason why DPD had the highest rate of per capita civilian killings of all U.S. police departments in 1971—four times the rate in New York City.163

In September 1971 five thousand protesters marched in Detroit demanding an end to STRESS and condemning the murders of the Attica rebels. Cockrel announced, “STRESS will be abolished. We’re going to show them discipline the man never knew existed in the black community.”164 He and radical groups like From the Ground Up presented STRESS as a “tool of those in power” used to intimidate and terrorize impoverished black Detroiters, and decried the increasing “utilization in the domestic law enforcement scene of new terminology, operating techniques, weaponry and equipment produced from the ‘test fields’ of counter-insurgency activity abroad.” From the Ground Up insisted, “We, the people of Detroit, need to confront the divisions brought about by the unjust and criminal distribution of wealth and control of life resources.”165

A 1973 poll found that 65 percent of black Detroiters disapproved and 78 percent of white Detroiters approved of STRESS.166 Many wealthier members of the black community, however, supported STRESS—signaling a growing class cleavage within the black community. Days after the 1971 protest, the Detroit News published an article titled “Black Leaders Support STRESS.”167 Black business organizations and black homeowners’ associations threw their support behind STRESS. The city’s main black newspaper, the Michigan Chronicle, published an article titled “STRESS Protest Shows Blacks Short on Foresight”:

The biggest issue in Detroit for the past four years has been crime in the streets. In recent months more aggressive enforcement, plus participation by citizens, has lessened the problem somewhat. . . . The civil disturbances of 1967 should remind black people not to attempt to destroy something they can’t replace. There is no merit in biting the hand that feeds you. It is understandable that many blacks harbor resentment against police because of past atrocities. But when one of these idle, nonproductive, soap box pork choppers calls a policeman “pig” while at the same time sucking on a barbecue bone, his thinking faculties are not together.168

This support persisted in spite of the fact that in their first thirty months of operation, STRESS units launched an estimated five hundred raids without search warrants. During one of these raids in 1972, STRESS officers murdered a Wayne County sheriff ’s deputy in what was believed to be an inner-police-department battle over control of the city’s drug trafficking. As Surkin and Georgakas write, after a fatal shootout involving three black militants,

“Commissioner Nichols went on television describing [the three men] as ‘mad-dog killers.’ In the weeks which followed, STRESS put the black neighborhoods under martial law in the most massive and ruthless police manhunt in Detroit history. Hundreds of black families had their doors literally broken down and their lives threatened by groups of white men in plain clothes who had no search warrants and often did not bother to identify themselves. Eventually, 56 fully documented cases of illegal procedure were brought against the department. One totally innocent man, Durwood Forshee, could make no complaint because he was dead.”169

It was not until the city’s first black mayor, Coleman Young, came into office in 1974 that the rogue police unit responsible for the deaths of at least twenty Detroit citizens was finally retired. But the demise of STRESS—which Young described as an “execution squad”—did not spell the end of aggressive anticrime measures. In fact the opposite was true: criminalization would only intensify as black liberals took control of Detroit’s political establishment.170

Race, Crime, and the 1973 Mayoral Election

Already the big question in cities like Detroit is whether a way can be found for these outsiders to live before they kill off those of us who are still working. How long can we leave them hanging out in the streets ready to knock the brains out of those still working in order to get a little spending money?—JAMES BOGGS, American Revolution, 1963

A long record of community activism, buoyed by a string of remarkable legal victories, led many to believe that Kenneth Cockrel was a viable candidate in the 1973 mayoral elections. But after considering a run, Cockrel decided against it, on the grounds the time was not yet ripe to seek revolutionary struggle inside mainstream political institutions (though by the late 1970s Cockrel changed his mind and successfully ran for city council).171

With Cockrel on the sidelines, the election pitted John Nichols, the city’s hard-nosed white police commissioner, against Coleman Young, a black state senator with a long history of labor organizing.172 Nichols ran on a straightforward law-and-order platform. But, as Stauch Jr. has documented, Young “made a powerful case as a more viable law-and-order candidate than the city’s own Police Commissioner.” In a speech one month before the election, Young declared Detroit to be the nation’s “murder capital” and claimed that Nichols had allowed the city’s crime problem to accelerate during his tenure as police commissioner. Young distributed campaign flyers that read, “Can you live with Detroit’s Crime Rates?” and “JOHN NICHOLS DID NOT DO THE JOB!”173

Young proposed a program of “law and order, with justice.” He said he would integrate and reform the police department, making it a “people’s police department,” while at the same time launching a broad initiative to stamp out criminals and defend the rights of crime victims. Rather than perpetuate the dragnet approach, which had drawn the ire of many in the black community, Young promised a “community policing” approach that would allow citizens to work closely with police in order to more precisely target criminals. In a speech to the Detroit Economic Club, Young promised to launch “more intensive undercover investigations” and to institute harsher laws for drug traffickers.174 He would help actualize Henry Ford II’s goal of making Downtown Detroit a “safe spot” to invest in. The black state senator further ingratiated himself with business leaders by insisting that the black community would stand behind his administration, whereas if Nichols was elected mayor, it would only fuel racial polarization and social unrest. “Who better than a black mayor,” Young asked, “can deal with the dudes on Dexter, on Livernois, and start turning things around?”175

Race proved central to the election. In an incredibly close final tally, Young eventually triumphed by securing 92 percent of the black vote, whereas Nichols took 91 percent of the white vote. In his famous inaugural address, Young declared:

I recognize the economic problem as a basic one, but there is also the problem of crime, which is not unrelated to poverty and unemployment, and so I say that we must attack both of these problems vigorously at the same time. The Police Department alone cannot rid this city of crime. The police must have the respect and cooperation of our citizens. But they must earn that respect by extending to our citizens cooperation and respect. We must build a new people-oriented Police Department, and then you and they can help us to drive the criminals from the streets. I issue a forward warning now to all dope pushers, to all ripoff artists, to all muggers: It’s time to leave Detroit; hit Eight Mile Road. And I don’t give a damn if they are black or white, or if they wear Superfly suits or blue uniforms with silver badges: Hit the Road.176

At Young’s inaugural celebration, black leaders shared the platform with the new mayor and supported him in his crusade against crime. U.S. District Court judge Damon Keith, for example, a former civil rights activist, challenged Young to “lead a revolt of the people of this community for justice and against crime” by “ridding this city, root and branch, of the criminals who are committing murders, rapes, and assaults on the people of this city.”177 One Detroit News reporter wrote, “The best-intentioned, strongest civil libertarian, most white mayor of Detroit . . . would have felt uncomfortable saying what Young and Keith said about crime.”178

The support for Young’s law-and-order campaign highlights the dialectic of repression and integration taking shape at the time. In the context of systematic violence against poor black Americans—from pervasive unemployment to state brutality and the systematic repression of dissident movements—a better regime of racial representation would be necessary if capitalism was going to legitimate itself in urban America. But as we will see in the next chapter, the integration of many middle-class black Americans into the political establishment occurred alongside, and was inextricably linked to, a deterioration in living standards among the poorer segments of the working class—a deterioration that continues to this day.

Notes

117 Richard Vogel, “Capitalism and Incarceration Revisited,” Monthly Review, September 1, 2003.

118 Loïc Wacquant, Punishing the Poor. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2009, 114; Michel Foucault, Discipline and Punish, translated by Alan Sheridan, New York: Vintage Books, 1995, 297, 306; Julia Felsenthal, “Ava Duvernay’s 13th Is a Shocking, Necessary Look at the Link between Slavery and Mass Incarceration,” Vogue, October 6, 2016.

119 George Jackson, Soledad Brother: The Prison Letters of George Jackson, Chicago: Lawrence Hill Books, 1994, 14; Jordan Camp, Incarcerating the Crisis, Berkeley: University of California Press, 2016, 71–72.

120 Quoted in Dan Berger, Captive Nation: Black Prison Organizing in the Civil Rights Era, Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2014, 159, 100.

121 Berger, Captive Nation, 129.

122 Manning Marable, Race, Reform, and Rebellion, Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 2007, 127.

123 Joshua Bloom and Waldo E. Martin Jr., Black against Empire: The History and Politics of the Black Panther Party, Berkeley: University of California Press, 2012, 378.

124 Camp, Incarcerating the Crisis, 71.

125 Camp, Incarcerating the Crisis, 82.

126 Berger, Captive Nation; Jesenia Pizarro and Vanja M. K. Stenius, “Supermax Prisons: Their Rise, Current Practices, and Effect on Inmates,” Prison Journal 84, no. 2 (2004), 251.

127 Camp, Incarcerating the Crisis, 88.

128 Pizarro and Stenius, “Supermax Prisons,” 251.

129 Dan Berger, “Social Movements and Mass Incarceration: What Is to Be Done?” Souls 15, nos. 1–2 (2015), 9.

130 Berger, “Social Movements and Mass Incarceration,” 9; Camp, Incarcerating the Crisis, 88.

131 Jackson, Soledad Brother.

132 Peter Linebaugh, The London Hanged, London: Verso, 2003, xxii.

133 Manning Marable, How Capitalism Underdeveloped Black America. Boston: South End Press, 1983, 124.

134 Morton Wenger and Thomas Bonomo. “Crime, the Crisis of Capitalism, and Social Revolution,” In Crime and Capitalism: Readings in Marxist Criminology, ed. David F. Greenberg. Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1993, 685.

135 James Forman Jr., Locking Up Our Own. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2017, 76, 20.

136 Robert H. Mast, Detroit Lives, Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1994, 172.

137 Heather Ann Thompson, Whose Detroit? Politics, Labor, and Race in a Modern American City, Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2001, 73; The coalition helped win support for the City of Detroit Fair Housing ordinance, an attempt to ameliorate some of the housing discrimination that had galvanized activists before and after the rebellion. Abayomi Azikiwe, “Lessons from the Detroit July 1967 Rebellion and Prospects for Social Transformation: Part 1 and 2,” 21st Century, July 28, 2017.

138 Michael Stauch Jr., “Wildcat of the Streets: Race, Class and the Punitive Turn in 1970s Detroit,” Unpublished dissertation, 2015. Cite Seer x; Stauch, “Wildcat of the Streets,” 179–83.

139 In one striking example of this dynamic, in Chicago there were myriad efforts to “incorporate gangs into the legitimate local power structure” in order to quell dissidence and violence among black youth to leverage more community development funding. In 1967 a $957,000 Office of Economic Opportunity grant “used the Woodlawn area’s existing gang structure—the Blackstone Rangers and the Devil’s Disciples—as the basis of a program to provide remedial education, recreation, vocational training, and job placement services to youths.” Also in 1967 the Vice Lords gang registered as a corporation and the next year received a $15,000 grant for an urban renewal campaign. Andrew J. Diamond, Chicago on the Make: Power and Inequality in a Modern City. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2017, 196.

140 David Goldberg, David, “From Landless to Landlords: Black Power, Black Capitalism, and the Co-optation of Detroit’s Tenants’ Rights Movement, 1964–1969,” in The Business of Black Power: Community Development, Capitalism and Corporate Responsibility in Postwar America, ed. Laura Warren Hill and Julia Rabig. Rochester, NY: University of Rochester Press, 2012, 170; Azikiwe, “Lessons from the Detroit July 1967 Rebellion.”

141 Thompson, Whose Detroit?, 85–88, 92, 101.

142 Thompson, Whose Detroit?, 80.

143 Heather Ann Thompson, “Unmaking the Motor City in the Age of Mass Incarceration.” Law and Society 15 (December 2014), 46; Adaner Usmani, “Did Liberals Give Us Mass Incarceration?” Catalyst 1, no. 3, 2017.

144 Campbell Gibson and Kay Jung, Historical Census Statistics on Population Totals by Race, 1790 to 1990, and by Hispanic Origin, 1970 to 1990, for the United States, Regions, Divisions, and States, Working Paper 56. Washington, DC: U.S. Census Bureau, Population Division, September 2002, “Table 23. Michigan—Race and Hispanic Origin for Selected Large Cities and Other Places: Earliest Census to 1990.”

145 George Hunter, “Dec. Surge Dims Hopes for Dip in Detroit Murders,” Detroit News, December 28, 2015; Usmani, “Did Liberals Give Us Mass Incarceration,” 174.

146 Stauch, “Wildcat of the Streets,” 355.

147 Stauch, “Wildcat of the Streets,” 372.

148 Stauch, “Wildcat of the Streets,” 355.

149 Dan Georgakas and Marvin Surkin. Detroit: I Do Mind Dying. Cambridge, MA: South End Press, 1998, 167. When considering the scope of the city’s crime problem, we have no choice but to disagree with Heather Ann Thompson. In “Unmaking the Motor City in the Age of Mass Incarceration,” she argues that rising crime reflected little more than the dubious nature of crime statistics. She also seeks to downplay the scope of the city’s homicide problem. “Despite the fact that the national homicide rate had risen from 5.5 per 100,000 people in 1965 to 7.3 in 1968, the nation’s citizenry—be it in the Delta or in Detroit—was not in fact suffering a record-setting crime wave. The murder rate had been far higher in the 1930s—as high as 9.7 per 100,000. Indeed, if one looks at the entire 20th century, it is remarkable how much safer the 1960s were compared to previous decades. Not only was a U.S. citizen less likely to be murdered in the early to mid-1960s than they were at other points in the 20th century, but their risk of meeting a violent death actually went up after the nation began a war on crime” (44). To be sure, the crime problem was exaggerated by political elites, but to deny the reality of a devastating crime problem is highly misleading.

150 Even the dissident group From the Ground Up (which was formed from the Motor City Labor League) wrote in the early 1970s, “One cannot speak of ‘high crime areas’ in Detroit. The entire city is such an area, though sections of the center city, riddled with poverty, police complicity in drug traffic, and double high rates of unemployment, are, to be sure, the ‘highest crime areas’” (Kathleen Schultz, Detroit under STRESS, Detroit: From the Ground Up, 1973., 9).

151 James Forman Jr., “Racial Critiques of Mass Incarceration: Beyond the New Jim Crow,” New York University Law Review 87 (2012), 114.

152 Huey P. Newton, The Huey Newton Reader, edited by David Hillard and Donald Weise, New York: Seven Stories Press, 2002,156; Robyn C. Spencer, The Revolution Has Come: Black Power, Gender, and the Black Panther Party in Oakland, Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2016; John Narayan, “The Wages of Whiteness in the Absence of Wages: Racial Capitalism, Reactionary Intercommunalism and the Rise of Trumpism,” Third World Quarterly 38, no. 11 (2017): 2482–500.

153 Amilcar Shabazz, “Ahmad A. Rahman’s Making of Black ‘Solutionaries.’” Journal of Pan African Studies 8, no. 9 (2015). Shabazz adds, “Long before Michelle Alexander’s book about mass incarceration and the ‘New Jim Crow,’ Rahman saw what was coming and attempted to counter it.”

154 Shabazz, “Ahmad A. Rahman’s Making of Black ‘Solutionaries.’”

155 Mark Jay, “Cages and Crises,” Historical Materialism 29, no. 1 (2019): 182–223.

156 Alex Vitale, The End of Policing, New York: Verso, 2017, 14.

157 Christian Parenti, “The Making of the American Police State,” Jacobin, July 28, 2015.

158 Vitale, End of Policing, 50.

159 Elizabeth Hinton quoted in Scott Kurashige, The Fifty-Year Rebellion: How the U.S. Political Crisis Began in Detroit, Berkeley: University of California Press, 2017, 27.

160 Robert Pavich, “The Little Lady May Be a Cop: Disguised Policeman to Fight Detroit Street Crime,” Detroit News, January 13, 1971. Jerome Scott remembers seeing suspicious things like drunken white guys walking around black neighborhoods with money falling out of their pocket. Author interview. March 5, 2019.

161 Schultz, Detroit under STRESS, 15.

162 Joe T. Darden and Richard W. Thomas, Detroit: Race Riots, Racial Conflicts and Efforts to Bridge the Racial Divide. East Lansing: Michigan State University Press, 2013, 50; Pavich, “The Little Lady May Be a Cop.”

163 Schultz, Detroit under STRESS, 4.

164 Stephen Cain, “4,000 Join in Orderly Protest against STRESS Killing,” Detroit News, September 14, 1971.

165 Schultz, Detroit under STRESS, 43, 57.

166 Schultz, Detroit under STRESS, x.

167 “Black Leaders Support S.T.R.E.S.S.,” Detroit News, September 24, 1971.

168 “Stress Protest Shows Blacks Short on Foresight: Slayton,” Michigan Chronicle, November 17, 1971.

169 Georgakas and Surkin, Detroit, 168, 171, 169–70. In another remarkable legal victory, Cockrel won a full acquittal for Hayward Brown, the militant accused in the shootout with police, not by claiming that Brown did not kill the police, but rather that STRESS was an illegitimate institution. Thompson, Whose Detroit?, 149–51, 194.

170 Schultz, Detroit under STRESS, 51.

171 Thompson, Whose Detroit?, 149–51, 194; Georgakas and Surkin, Detroit, 220.

172 William K. Stevens, “Mayoral Primary Heed in Detroit,” New York Times, September 12, 1973.

173 Stauch, “Wildcat of the Streets,” 70, 78–79.

174 Stauch, “Wildcat of the Streets,” 81; Thompson, Whose Detroit?, 198.

175 Robert Pisor, “Young—A Student of the Streets; New Mayor Shares Crime Victims’ Concerns,” Detroit News, November 7, 1973.

176 Inaugural Speech, 1974, in Coleman A. Young Collection, part II, box 106, folders 4–5, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University.

177 Stauch, “Wildcat of the Streets,” 91–92.

178 Quoted in Stauch, “Wildcat of the Streets,” 93–94.

Excerpted with permission from Mark Jay and Philip Conklin, A People’s History of Detroit, copyright Duke University Press, 2020, pp. 183-94, 272-75.

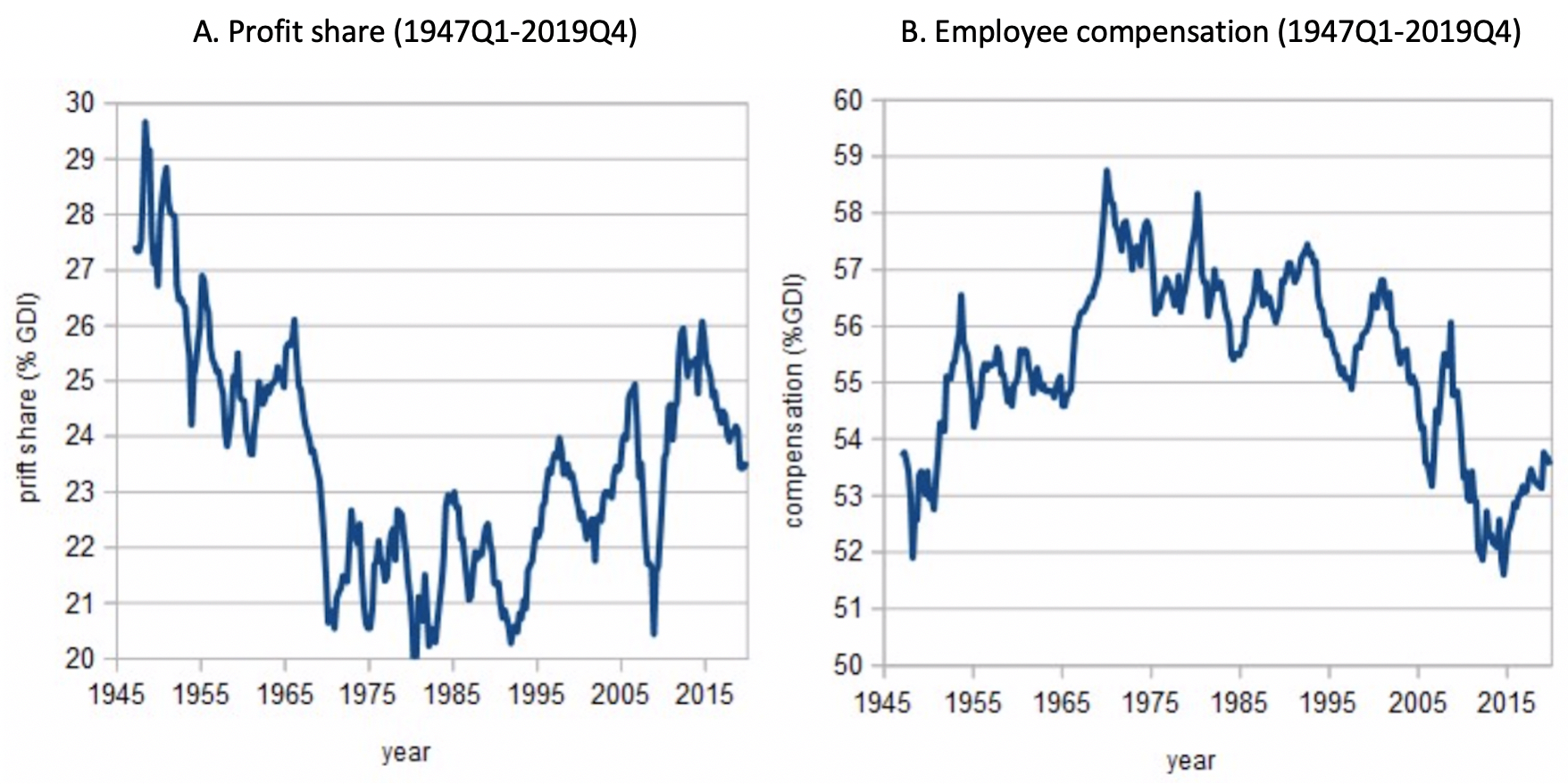

Figure 1: A. Profit share (net operating surplus as percent of gross domestic income), 1947-2019.

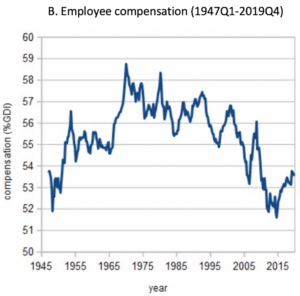

Figure 1: A. Profit share (net operating surplus as percent of gross domestic income), 1947-2019. Figure 1: B. Employee compensation as percent of gross domestic income, 1947-2019.

Figure 1: B. Employee compensation as percent of gross domestic income, 1947-2019.

For the past four months Covid-19 has revealed the contradictions and unsustainability of global capitalism perhaps in a manner that no other single phenomenon has ever done in history. The virus has become the latest and arguably the bleakest reminder that capitalism’s systemic dynamics and imperatives, i.e. its relentless drive for competitiveness and profitability, is bound to sooner or later disrupt the very foundations of human existence as a whole. Furthermore, the biological blitzkrieg activated by the coronavirus has arrived at a time when the global political economy has already been going through two other major crises – crisis of ‘development’ and crisis of democracy – which will be aggravated by the current pandemic. This short essay provides a synopsis of capitalism’s triple crisis, which is critical to develop a balanced assessment of what the post-pandemic world may look like.

For the past four months Covid-19 has revealed the contradictions and unsustainability of global capitalism perhaps in a manner that no other single phenomenon has ever done in history. The virus has become the latest and arguably the bleakest reminder that capitalism’s systemic dynamics and imperatives, i.e. its relentless drive for competitiveness and profitability, is bound to sooner or later disrupt the very foundations of human existence as a whole. Furthermore, the biological blitzkrieg activated by the coronavirus has arrived at a time when the global political economy has already been going through two other major crises – crisis of ‘development’ and crisis of democracy – which will be aggravated by the current pandemic. This short essay provides a synopsis of capitalism’s triple crisis, which is critical to develop a balanced assessment of what the post-pandemic world may look like.

This article is being published simultaneously in the Australian journal

This article is being published simultaneously in the Australian journal

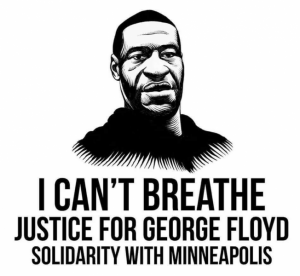

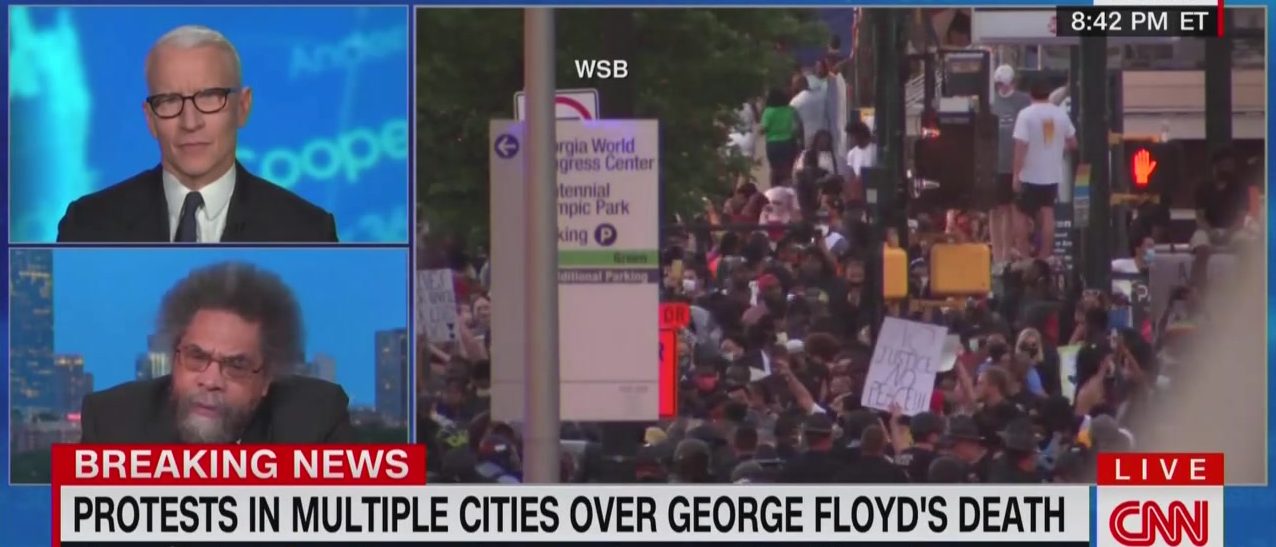

Dr. Cornel West said on Friday we are witnessing the failed social experiment that is the United States of America in the protests and riots that have followed the death of George Floyd at the hands of Minneapolis police. West told CNN host Anderson Cooper that what is going on is rebellion against a failed capitalist economy that does not protect the people. West, a professor, denounced the neoliberal wing of the Democratic Party that is all about “black faces in high places” but not actual change. The professor remarked even those black faces often lose legitimacy because they ingratiate themselves into the establishment neoliberal Democratic Party.

Dr. Cornel West said on Friday we are witnessing the failed social experiment that is the United States of America in the protests and riots that have followed the death of George Floyd at the hands of Minneapolis police. West told CNN host Anderson Cooper that what is going on is rebellion against a failed capitalist economy that does not protect the people. West, a professor, denounced the neoliberal wing of the Democratic Party that is all about “black faces in high places” but not actual change. The professor remarked even those black faces often lose legitimacy because they ingratiate themselves into the establishment neoliberal Democratic Party.

That Cuban doctors are being sent abroad by their government to help with the current COVID-19 health crisis is obviously a welcome thing. To those on the receiving end, it is undoubtedly a priceless, life-saving gift. For many people it is one more expression of the Cuban state’s progressive character. Yet, it is important to bring out lesser known aspects of this Cuban doctors abroad program, including the financial benefits obtained by the government, and the conditions under which its doctors labor on the island and abroad that expose the Cuban state’s undemocratic character and the impact that this has on the Cuban people.

That Cuban doctors are being sent abroad by their government to help with the current COVID-19 health crisis is obviously a welcome thing. To those on the receiving end, it is undoubtedly a priceless, life-saving gift. For many people it is one more expression of the Cuban state’s progressive character. Yet, it is important to bring out lesser known aspects of this Cuban doctors abroad program, including the financial benefits obtained by the government, and the conditions under which its doctors labor on the island and abroad that expose the Cuban state’s undemocratic character and the impact that this has on the Cuban people.

The Covid-19 pandemic and the worldwide lockdown have triggered a depression as great as that of the 1930s. The causes of this crisis, the character of government policies, and the programs put forward by working class groups are of concern to all of us. So, to look into these questions, we spoke with Eric Toussaint, a leading analyst of these matters.

The Covid-19 pandemic and the worldwide lockdown have triggered a depression as great as that of the 1930s. The causes of this crisis, the character of government policies, and the programs put forward by working class groups are of concern to all of us. So, to look into these questions, we spoke with Eric Toussaint, a leading analyst of these matters.

[Introduction by Mark Jay and Philip Conklin] In 1965, the correctional population in the U.S., including all those in jail or prison, or on probation or parole, was less than 800,000. At present, the number is around seven million. As a result of this historically unprecedented rise—commonly known as “mass incarceration”—approximately

[Introduction by Mark Jay and Philip Conklin] In 1965, the correctional population in the U.S., including all those in jail or prison, or on probation or parole, was less than 800,000. At present, the number is around seven million. As a result of this historically unprecedented rise—commonly known as “mass incarceration”—approximately

There’s a famous book by the French Marxist Henri Lefebvre called Le Droit à la ville, which translates to The Right to the City. Written in 1968, Lefebvre was critical of the increasing sway that capitalism had over the city, and the resulting commodification of urban life and decline of the collective urban experience. In response, Lefebvre envisioned “the right to the city.” He did not picture the right to the city as a rigid legal right, but rather as a continual right of the urban working class to democratically and collectively change the city. Lefebvre imagined cities in which all urban dwellers could shape and reshape the city, to both contribute to its rich fabric and benefit from its cultural and material production. The right to the city, as the geographer David Harvey

There’s a famous book by the French Marxist Henri Lefebvre called Le Droit à la ville, which translates to The Right to the City. Written in 1968, Lefebvre was critical of the increasing sway that capitalism had over the city, and the resulting commodification of urban life and decline of the collective urban experience. In response, Lefebvre envisioned “the right to the city.” He did not picture the right to the city as a rigid legal right, but rather as a continual right of the urban working class to democratically and collectively change the city. Lefebvre imagined cities in which all urban dwellers could shape and reshape the city, to both contribute to its rich fabric and benefit from its cultural and material production. The right to the city, as the geographer David Harvey

[This is a verbatim transcript of Episode 73 of the podcast titled RevolutionZ.]

[This is a verbatim transcript of Episode 73 of the podcast titled RevolutionZ.]

This article was written for L’Anticapitaliste, the weekly newspaper of the New Anticapitalist Party (NPA) of France.

This article was written for L’Anticapitaliste, the weekly newspaper of the New Anticapitalist Party (NPA) of France.

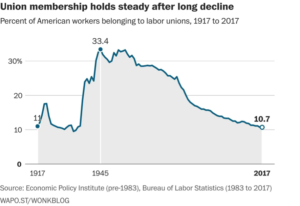

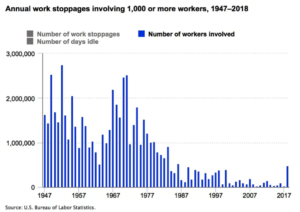

Many younger radicals today are trying to figure out how to relate, personally and collectively, to the labor movement.

Many younger radicals today are trying to figure out how to relate, personally and collectively, to the labor movement.

This is the transcript of a talk originally given on April 4, 2020 as part of an online meeting titled “

This is the transcript of a talk originally given on April 4, 2020 as part of an online meeting titled “