The passionate uprising that began in Minneapolis after police murdered George Floyd quickly spread across the country and around the world, is now the biggest upheaval since 1968. It beautifully illuminates the power and possibility for revolution in the raging fires of burning police precincts and cop cars. But in order for this passion, this righteous rage, to succeed in the face of intensifying police repression, mobilized National Guards, and a military standing ready for urban warfare, the movement must transform itself for sustained rebellion.

The passionate uprising that began in Minneapolis after police murdered George Floyd quickly spread across the country and around the world, is now the biggest upheaval since 1968. It beautifully illuminates the power and possibility for revolution in the raging fires of burning police precincts and cop cars. But in order for this passion, this righteous rage, to succeed in the face of intensifying police repression, mobilized National Guards, and a military standing ready for urban warfare, the movement must transform itself for sustained rebellion.

From the moment Trump announced his candidacy for president, many have warned that he is a fascist and of the broader threat he represents. He admires dictators and wants to be president for life, uses phrases like “civil war” as trial balloons, asserts he has absolute power, and is blaiming Democrats for trying to steal the upcoming election, while the Attorney General weaponizes this rhetoric in a dangerous narrative of theocratic crusade. Reacting to the uprising, Trump has incited white supremacist violence, branded anti-fascists as terrorists, deployed an unmarked army in DC, and wants to “dominate” the nation. We must confront the possibility that this imperialist metropole, settler-colonial empire, and authoritarian state otherwise known as the US republic will further degenerate toward fascism. Trump is using the passionate uprising as an excuse to continually intensify state repression, sowing chaos and fear as a means to remain in power. Trump, like Hitler and his own coup, wants to “provoke the semblance of civil war.”[1] The uprising may be his own “Reichstag fire moment.”

During the government shutdown over border wall funding that ended January 2019, many raised concerns over Trump’s national emergency powers and a further descent into fascism. In response to Michael Cohen’s congressional testimony, Robert Reich, Nancy Pelosi, and others worried that Trump may not leave office if he loses this November. Using the pandemic and recession it triggered as cover, Trump and the death cult formerly known as the Republican Party are orchestrating a coordinated assault on whatever democracy still remains. The threat of a broader fascist seizure of power continue to grow, as far-right paramilitary forces provoke the “semblance” Trump seeks. If Trump refuses to leave after being defeated in November, if he seizes upon a “failed” or “delayed” election, takes us to war with Iran, Venezuela, and/or China to remain in power, or massively intensifies repression to quell dissent, including if he “wins” reelection, we must be prepared.

We need militant infrastructure organized as part of a growing systemic alternative; people’s assemblies rooted in the mutual aid necessary to sustain the rebellion and coordinate strike waves as the election draws near. We are witnessing rising worker militancy in wildcat strikes, rent strikes with rapidly spreading tenant unions, mutual aid proliferating in response to pandemic, and now a passionate uprising in over 500 cities. There is widespread recognition of the fascist threat that stands against us. To not seize this moment to help sustain the passionate uprising in the streets, we risk annihilation. In the recent words of a Jewish Auschwitz death camp survivor, “one day you wake up and it’s too late.” We must make sure that day does not arrive, again.

Prior to the murder of George Floyd and the passionate uprising sparked by his death, an organization in Mississippi called Cooperation Jackson put out a call for an ongoing series of monthly strikes. Together with those who responded, they established People’s Strike with actions that began May 1st. The monthly actions were not intended to be a general strike, a work stoppage at a singular point in time with the intent to sustain until demands are met. They are a series of actions on the first of each month going forward; “non-violent direct action conducted in a coordinated campaign” in hopes of leading to a general strike in the future. Against the threat of a broader fascist seizure of power, building a sustained rebellion capable of launching a general strike around the elections is critical.

As part of their own efforts, Cooperation Jackson built what they call “People’s Assemblies.” They are “a vehicle of democratic social organization that, when properly organized, allows people to exercise their agency, exert their power, and practice democracy…in its broadest terms.”[2] Their first assembly came out of mutual aid work within the Mississippi Disaster Relief Coalition that emerged in response to Hurricane Katrina.[3] Today, the disaster is white supremacist violence, a police state, and a fascist threat. If People’s Assemblies were to spread within the passionate uprising as a form of self-organization, their role would likely fluctuate with the ebb and flow of a sustained rebellion itself, that is, for both offense and defense.

They “can function as a genuine ‘dual power’ and assume many of the functions of the government,” while also to “defend the people…fight to maintain as many of the gains it won as possible, and prepare for the next upsurge.”[4] People’s assemblies can be democratic spaces for the articulation of movement goals and demands, the coordination of mutual aid like solidarity kitchens to sustain the struggle, for community-based self-defense forces, and more. The question becomes whether or not we will see these forms of democratic self-organization proliferate. With Trump intensifying state repression as the threat of fascism barrels toward us with the November elections, time is fleeting. We can, however, turn to numerous recent examples from around the world for inspiration and lessons, just as we can look to the history of struggles here.

Mutual Aid, People’s Assemblies, and Strikes: Puerto Rico, Chile, and France

In response to Covid-19, communities come together in mutual aid efforts throughout the so-called United States with widespread media coverage. Practices include aggregating and delivering groceries, medicine, and other essential supplies. Some make and deliver pre-packaged, prepared meals. Some provide services including translation or interpretation, running general errands, childcare, eldercare, and mental health support. Some have also taken on the DIY production of face masks, hand sanitizer, and cleaning solution.

It’s Going Down and Mutual Aid Disaster Relief both maintain growing lists of these undertakings, while Resource Generation maintains a list of mutual aid funds. Amidst the economic depression triggered by pandemic, mutual aid practices will only increasingly become necessary in order for this passionate uprising of righteous rage to sustain itself. We are already seeing it emerge within protests in Brooklyn and DC, though it will take more than “ad hoc supply chains” to sustain this struggle. To sustain, we will also need systems like People’s Solidarity Brigades. Yet, it is within the experience of rage then passionately taking to the streets that imbues within us a feeling and recognition of our power, that the systems we put in place to sustain this rebellion are the tools of our collective liberation.

In the aftermath of Hurricane Maria September 2017, mutual aid efforts proliferated throughout Puerto Rico. Out of the horrific devastation, communities came together to provide immediate necessities that, coupled with longstanding political efforts, would eventually be utilized to support a mass uprising, forcing Governor Rossello to resign late July 2019. Indeed, in the depths of trauma there is also passion, seared into our hearts, aching to be unleashed against those responsible.

As part of the uprising, communities formed democratic assemblies as spaces for the coordination of mutual aid and to build popular power against the neocolonialist government. Together, these neighborhood-based assemblies continually reproduced the capacity for sustained rebellion as the kernel of a systemic alternative. To feel freedom in the streets is one thing. To feel freedom in a growing system built for liberation is another and it is this feeling that sustains our passion. Though mutual aid efforts arising in response to the pandemic across the 50 states are not yet accountable to or coordinated by neighborhood-based democratic assemblies, they could be.

Recent strikes in Chile, temporarily halted only by pandemic, found support within a decades-long history of territorial assemblies. Amidst the uprising, assemblies proliferated in neighborhoods throughout the country, providing space for the articulation of movement goals and demands. Alongside these political dimensions, they were simultaneously spaces to coordinate mutual aid for neighbors to both survive an economy brought to a halt and to maintain capacity for sustaining collective struggle.

These assemblies were also an “antidote to people’s anxiety and isolation” just like they were used to organize community self-defense forces and foster an “emerging culture of rebellion.” Popular assemblies became the form of self-organization for the movement itself, rooted in a growing systemic alternative that not only fed and sheltered the uprising, but fueled its spirit, the passion to endure against all odds, and a feeling of liberation found in the struggle itself.

With France and the movement of the Yellow Vests (YVs), weekly Saturday mass demonstrations began November 2018. They included street blockades with some turning into occupations, while others were temporary measures to shut down main transportation routes. By the end of January 2019, the movement had over a hundred autonomous assemblies across the country that sent delegates to the first “Assembly of Assemblies.” As part of the ongoing struggle, assembly delegates gathered three more times; in April, July, and then November, where they ratified support for the December 5th general strike called by labor unions.

The YV’s form of radical democratization became the system of self-organization for the general strike itself, keeping power in the hands of striking workers and communities, not established labor bureaucracies. What began as mutual aid arising out of the blockades, occupations, and assemblies took on an additional form as well; that of democratically self-managed strike funds. Emerging from and being controlled by strikers, these funds both ensured greater capacity to sustain the strike, while enhancing the movement’s autonomy. To those who felt our collective power as they watched cop cars burn, imagine the feeling of being part of a rebellion sustained by a rising system that we, ourselves, govern. When organized, we can “set fire” to everything.

Each of these three examples point to an intimate relationship between mutual aid, democratic assemblies, and strikes. They are, by far, not the only useful sources of inspiration or lessons. The history of struggles for Black liberation is also a history of mutual aid in service of militant movements. We can also go back through the entire history of the labor movement and find countless examples of mutual aid, including its role in general strikes. But what this should really teach us is the power within us to build the world anew, even amidst its darkest moments.

Mutual Aid in Struggles for Black Liberation

Returning to Cooperation Jackson, Kali Akuno and Ajamu Nangwaya look to revolutionary Amilcar Cabral; advocating “cooperatives and the practice of democratic self-management, mutual aid and solidarity” for “the Black working class in Jackson (and well beyond)” in order to “respond to their here-and-now daily needs,” while offering “a vision of how to solve the major issues confronting society that limit their freedom and constrain their aspirations.”[5] In addition to the People’s Assemblies, they are building a solidarity economy, defined as “a process promoting cooperative economics that promote social solidarity, mutual aid, reciprocity, and generosity.” In part, it “is inspired by the Mondragon Corporation, a federation of mostly worker cooperatives and consumer cooperatives.”[6] This is not Cooperation Jackson’s only inspiration by any means, but when it comes to building a solidarity economy to sustain a rebellion capable of defeating fascism today, emulating Mondragon now risks annihilation. Fortunately, the history of mutual aid in struggles for Black liberation point to another approach, and one that can emerge from the uprising itself.

Mondragon was started in Spain not to fight fascism, but to peacefully coexist with Franco’s authoritarian regime that had violently seized control, utilizing support from Hitler to defeat a revolutionary left that had gained power. Amidst pandemic, economic depression, intensified state repression, and Trump itching to destroy the last democratic vestiges of the republic to remain in power, starting cooperative businesses that compete in the capitalist market will only heighten our vulnerability.

Before he was assassinated in 1969, Fred Hampton warned us: “Nothing’s more important than stopping fascism, because fascism will stop us all.” In this era of ascendant christian nationalism and white supremacy, the continuation of a long legacy of American fascism that inspired Hitler himself, Trump now has “The Surge;” militarized police allies standing with him and brutally repressing protests, yet this is further galvanizing public support for those in the streets. We need a solidarity economy that emerges from this passionate uprising, becoming the infrastructure necessary for it to become a sustained rebellion.

In RaceBaitr, Nakia S. argued that “Black life is a constant practice of mutual aid work” today. Looking historically, Angela Davis argued there is an “unbroken line of police violence in the United States that takes us all the way back to the days of slavery.” For political economist Jessica Gordon Nembhard, mutual aid in the struggle against this “unbroken line” of violence goes all the way back to at least 1780, organized as informal mutual aid cooperatives or assemblies.[7] Importantly, “for two centuries,” collectively pooling resources for mutual aid was a constant practice, especially for those who “did not earn a regular wage or even own their own bodies.”[8] For those today who “feel we are drowning, slowly going insane with rage,” not fighting to overthrow a white supremacist system risks death by despair. In passionately rising, we each reconnect with our trauma, feel the pain passed down to us, harnessing it as a weapon to sustain rebellion and defeat the fascist threat that stands against us.

Early mutual aid provided the means and structure for “maroon outlaw communes,” utilizing informal “cooperatives in the form of insurrection.”[9] Mutual aid would eventually proliferate across many parts of the country as democratic assemblies for a solidarity economy.[10] In these “mutual aid societies,” people each contributed an initial small sum of money to join, which would go into a common fund. Communities came together to pool “‘meager resources’…that even the ‘poorest women managed to contribute’ to meet vital social needs.” Each person would contribute an ongoing fee into this common fund as well, much like union dues. Members would decide how funds were to be used based on the democratic principle of one member, one vote.

Most often, funds would be used to provide “basic needs of everyday life – clothing, shelter, and emotional and physical sustenance.”[11] In NYC alone, “By 1898, 15 percent of Black men and 52 percent of Black women…belonged to a mutual-aid society.”[12] These democratically governed mutual aid societies were like People’s Assemblies, but with an organized capacity for mutual aid. This could become the form of self-organization for a sustained rebellion. Existing mutual aid efforts, especially newer efforts that emerged in response to pandemic, could look to this history and evolve. In doing so, by becoming a radically democratic form of self-organization as incipient systemic alternative, they would more closely embody “solidarity not charity,” while building capacity to support a sustained rebellion.

Looking to this history within struggles for Black liberation is not only something for existing mutual aid efforts to consider. People’s Assemblies rooted in mutual aid could also emerge from sites of struggle in streets throughout the country. This approach fosters autonomy and self-organization, including through the democratic governance of a grassroots fund whose usage can evolve with the needs of the rebellion. This too can become a weapon for tough minds and soft hearts in the battles to come.

Modeled after the Black Panther Party’s “National Committees to Combat Fascism,” communities are coming together for organized resistance. Though the Panther’s approach was criticized as placating white liberals, for this new effort to become a “fighting united front,” it will require coordinated self-defense forces, which can be funded and organized through mutual aid assemblies. In the Panther’s hometown of Oakland, we see a local food system reorient itself around sustaining the uprising, while addressing food deserts at the same time. Those on the front lines of the struggle know what they need better than anyone and the formation of People’s Assemblies grounded in mutual aid can foster what is required to sustain this passionate rebellion. We must imagine the collective power we would feel when thriving beyond the reach of toxic systems dedicated to our subservience, and build accordingly for our liberation.

A sustained rebellion grounded in People’s Assemblies for the coordination of mass non-violent direct action, while being rooted in mutual aid, could become a systemic alternative that sufficiently addresses what Akuno and Nangwaya advocated; meeting the “here-and-now” and embodying the necessary “vision.” Looking to mutual aid societies in historical struggles for Black liberation could do both from below and to the left. Though it remains to be seen whether or not a united front would coalesce in support of a sustained rebellion, there are groups who would be well-positioned to help a solidarity economy grow out of these assemblies, empowering a sustained rebellion that amounts to what Huey P. Newton said with regard to the Black Panther Party’s “survival programs,” that is, “survival pending revolution.”[13]

Mutual Aid, Assemblies, and Strikes: Historical Struggles of the Labor Movement

Despite the fact that major labor unions remain mired in their support for cancerous police unions, the labor movement itself overflows with reasons to remain hopeful in the revolutionary potential of a sustained rebellion against fascism. This is true today outside of the traditional union bureaucracies just as it is in the history of mutual aid, assemblies, and strikes in labor struggles.

Labor militancy erupted in 2019 with a wave of wildcat strikes now spreading across the country in the wake of pandemic. Workers at large corporations struck May 1st. Outside the traditional labor unions, these self-organized workers are assemblies unto themselves, adding to an emergent systemic alternative. Amazon workers in Chicago recently struck without a union for paid time off and won, a workers’ assembly of sorts that utilized mutual aid through a “solidarity committee” to ensure their capacity for struggle. Coordinated mutual aid has been part of the labor movement from the beginning. When systems of oppression inflict trauma upon us, we turn to those similarly afflicted and fight together.

Workers in 1768 organized what historian John Curl called the “first recorded wage earners’ strike against a boss in America.” Without union or strike fund, they built an informal cooperative based on mutual aid in order to democratically share resources to endure the struggle.[14] The more formal unions that emerged in the 1830s began as similar mutual aid efforts.[15] This same approach would even be used as the basis for their earliest political parties and could be used today for explicitly revolutionary “parties of autonomy.”[16] During the strike wave of 1877, mutual aid spontaneously erupted as forms of self-organization among striking workers and communities, one prominent example being the “Pittsburgh Commune.”[17] Even without the major unions, history shows us that sustained rebellion is possible and that the kernel of our revolutionary alternative can be but moments away.

Out of this strike wave, the Knights of Labor would grow to prominence and, initially at least, regarded their local unions as autonomous mutual aid assemblies for the purpose of enhancing labor militancy.[18] The revolutionary Socialist Labor Party would adopt a similar approach with Albert Parsons, a Haymarket martyr, calling these assemblies, these workers’ councils, “an autonomous commune in the process of incubation.”[19] Their broader “Pittsburgh Proclamation” further codified this approach.[20] With a passionate uprising taking place in streets across the country, this should give pause to every worker, recognizing both the necessity of struggle and the power to be found in one another.

In the early twentieth century, the Indstrial Workers of the World would organize transitory “encampments with cooperative survival networks” to support and organize among migrant workers.[21] During the 1919 Seattle General Strike, cooperative grocery stores provided food to strikers, while mutual aid efforts were organized across the city, including “twenty-one eating places” with “thirty thousand meals a day served to whoever needed one.”[22] In the 1934 San Francisco General Strike, newly emerged self-help or mutual aid cooperatives like the Universal Exchange Association became a way for striking workers and communities to support one another.[23] In those moments where we depend on one another for survival against tremendous odds, this history shows us that people rise to the occasion.

What could emerge from workplace and community-based assemblies, supporting a sustained rebellion against fascism, is only limited by our imagination and preparation. If these sorts of workers’ assemblies were to more prominently emerge within the increasingly militant grassroots labor movement, together with assemblies proliferating from the passionate uprising in streets across the country, this kernel of a systemic alternative could become a sustained rebellion with revolutionary potential, especially if Trump attempted a broader fascist seizure of power and we were ready to grind this country to a resounding halt.

Broadening Support for a Sustained Rebellion

The fascist threat Trump represents seeks to intensify all systems of oppression, while leading us down the path of climate destruction. As long as this threat is widely felt and perceived, there is every reason to believe support for this passionate uprising will grow, along with the recognition that our future rests in each other’s gentle, yet powerful hands. Without compromising the necessity of a sustained rebellion being Black-led, where else can we look for other terrains of struggle coalescing in support for a sustained rebellion?

On May 1st, then again on June 1st, the largest rent strike in decades took place as the latest expressions of a rising movement around formations like We Strike Together and the Autonomous Tenants Union Network. As it is being practiced today, mutual aid is necessary to survive these tumultuous times, including among tenants. The proliferating tenants unions or councils are forms of community-based assemblies, mutual aid efforts much like early labor militancy. With the pain inflicted by the pandemic and what will likely be a prolonged depression for many, the need for tenant organizing and rent strikes will only continue to grow. Coordinated mutual aid and a sustained rebellion will no doubt be required in order to succeed. We certainly cannot count on Congress.

Amidst pandemic, recession, and the threat of fascism, climate devastation has not gone away. We have now witnessed what Trump’s climate policies amount to, so him remaining in office will result in untold suffering. Over 600,000 people in all 50 states joined the September 2019 climate strike. 350.org recently called on the climate movement to support the passionate uprising taking place in cities across the country. A renewed climate strike effort supporting the formation of people’s assemblies, rooted in mutual aid to sustain a rebellion against the fascist threat, is necessary to avoid climate annihilation. If the upcoming elections do amount to a tipping point in the rise of fascism, the struggle against climate crisis will either become impossible or require precisely this degree of militancy. But what can emerge in even the most treacherous of circumstances can be as beautiful as it is powerful and profound.

Standing Rock should remain a lesson for all of us in these trying times, as should other forms of indigenous mutual aid. From April 2016 to February 2017, Water Protectors withstood massive state violence to stop the Dakota Access Pipeline. Despite the powerful forces standing against them, mutual aid within the encampment proved stronger. In “A Lesson in Natural Law,” Marcella Gilbert recounted the spirit that emerged in the heart of the movement as “people immediately began to resurrect our original systems of governance.” What began as modest systems of social reproduction would eventually become “the fourth largest ‘town’ in North Dakota.” Reflecting on it, Gilbert wrote that the “world of humanity hopes for proof: proof that life will sustain itself in the face of recklessness” and that “Standing Rock provided a place for life to thrive within a world of war, violence, and hopelessness.”[24] The passionate uprising is more of this proof, yet it needs to be capable of sustaining itself, including to be able to hold territory like Water Protectors, who have fought white supremacy countless times before.

Violent hate groups continue to reach record highs and the relentless murdering of trans folk must be combated. LGBTQ communities remain particularly vulnerable to the pandemic and righteous calls to communize the family are growing again. For those who lived through the HIV/AIDS crisis, governmental ineptitude is familiar, yet abounding threats drives them to fight harder, much like the legacy of the Stonewall Riot. Coordinated assaults on Roe v. Wade are part of a multi-pronged attack on women that has intensified throughout Trump’s presidency, and now under cover of pandemic. From the 2016 Women’s March to recent remarks by co-chair Tamika Mallory, the trauma inherent in Trump’s threat of hetero-patriarchy is palpable and interconnected, as is the fury to fight back.

Women ran mutual aid societies in the struggle for Black liberation from the 18th to the early 20th century.[25] It played a role in the Combahee River Collective in the 1970s as “an emotional support group” to learn from trauma. With 19th century revolutionary socialist feminist struggles in France and Russian communist feminist movements in the early 20th, mutual aid has long been a critical component in the struggle for women’s liberation.[26] In one example, women led rent strikes in NYC during the 1918 “Spanish flu” outbreaks, which also required mutual aid. Women’s leadership in mutual aid efforts remains the case today as well, however, we must also communize care work to equitably, collectively, and emotionally sustain us in struggle.

Horrific concentration camps now bring death by pandemic, yet hunger strikes continue. ICE forces people to seek refuge in places of worship, so over 1,100 communities stand together in a Sanctuary Movement to build collective defense with the undocumented. From the beginning, these efforts were grounded in mutual aid, exemplified in the Sanctuary in the Streets network. Built by the Pioneer Valley Workers Center, this too is grounded in assemblies. Furthermore, the Day Without Immigrants in 2017 could be organized again for the near future, rising with sociedades mutualistas. From recent Supreme Court terror to Trump’s deployment of “border patrol tactical units;” the fascist threat is widely felt and perceived. If the 2020 elections do amount to a tipping point and the threat standing against us is clear, with the right preparations, we could be unstoppable. But we must sustain a passionate rebellion, including to strike when our enemy is most vulnerable to rid the country of fascism once and for all.

Like in Charlottesville in 2017, countless communities have come together to protest against fascist marches and events, recognizing the inherent threat they pose. After the white “Christian” supremacist murders at the Tree of Life synagogue in Pittsburgh 2018, thousands took to the streets when Trump came to town. Violence against Jewish people has continued to rise, yet those like Never Again Action push forward with direct actions to shut down ICE and its concentration camps. On January 27th, 2020, the 75th anniversary of the liberation of the Auschwitz death camp, over 200 survivors came together to remind the world that we must be prepared. Meager impeachment attempts came and went, so will the plethora of progressive organizations that supported impeachment rallies now mobilize for a sustained rebellion? Or will they choose vital electoral efforts at the expense of all other preparedness?

There is tremendous power and potential now seething in anger out of the suffering forced upon us. In preparing for the possibility of a broader fascist seizure of power, weaving together the kernel of our own systemic alternative, forging the mutual aid assemblies necessary for a sustained rebellion and strikes against fascism, we can emerge victorious. Though the future is unwritten, counting on the republic being able to endure Trump and the “death cult” formerly known as the GOP is a dangerous gamble with people’s lives. We must ensure we do not follow the path of the democratic socialists in Germany against Hitler, who “had dampened the powder so long, in their fear lest it should explode, that when they finally and with a trembling hand applied a burning fuse to it, the powder did not catch.”[27] Supporting this passionate rising, building our collective capacity for a sustained rebellion as the November elections draw near, is the only guarantee we have against the fascist threat that seeks to plunge our world into darkness. Fascism is like an animal afflicted with rabies; desperate and dangerous. But it is not long for this Earth and the most humane thing to do is put it out of its misery.

[1] Leon Trotsky, The Struggle Against Fascism in Germany, (New York: Pathfinder Press, 1971). P. 341.

[2] Kali Akuno, “People’s Assembly Overview: The Jackson People’s Assembly Model,” in Jackson Rising: The Struggle for Economic Democracy and Black Self-Determination in Jackson, Mississippi, edited by Cooperation Jackson and Ajamu Nangwaya, (Ottawa, Daraja Press, 2017). P. 86-97.

[3] Ibid, “The Jackson-Kush Plan: The Struggle for Black Self-determination and Economic Democracy,” in Jackson Rising, 73.

[4] Ibid, “People’s Assembly Overview: The Jackson People’s Assembly Model,” in Jackson Rising, 96.

[5] Kali Akuno & Ajamu Nangwaya, “Toward Economic Democracy, Labor Self-management and Self-determination,” in Jackson Rising, 53.

[6] Kali Akuno, “The Jackson-Kush Plan: The Struggle for Black Self-determination and Economic Democracy,” in Jackson Rising, 76-77.

[7] Jessica Gordon Nembhard, Collective Courage: A History of African American Cooperative Economic Thought and Practice, (University Park, Pennsylvania State University Press, 2014), P. 40-47.

[8] Ibid, 31.

[9] Ibid, 34.

[10] Ibid, 31-47.

[11] Ibid, 43.

[12] Ibid, 44.

[13] David Hilliard, The Black Panther Party: service to the people programs, (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 2008). P. 3-4.

[14] John Curl, For All the People: Uncovering the Hidden History of Cooperation, Cooperative Movements, and Communalism in America, (CA: PM Press, 2009). P. 32-33.

[15] Ibid, 38-44.

[16] Ibid, 44-46.

[17] Ibid, 86.

[18] Ibid, 87-88.

[19] Paul Avrich, The Haymarket Tragedy, (New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 1984). P. 72-73.

[20] Ibid, 73-77.

[21] Curl, For All the People, 127.

[22] Ibid, 148-149.

[23] Ibid, 177-178.

[24] Ibid, 288.

[25] Nembhard, Collective Courage, 43.

[26] Carolyn J. Eichner, Surmounting the Barricades, (Indiana: Indiana University Press, 2004). P. 24-26. & Alexandra Kollontai, Selected Writings of Alexandra Kollontai, (New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 1877). P. 54-55.

[27] Trotsky, The Struggle Against Fascism in Germany, 190.

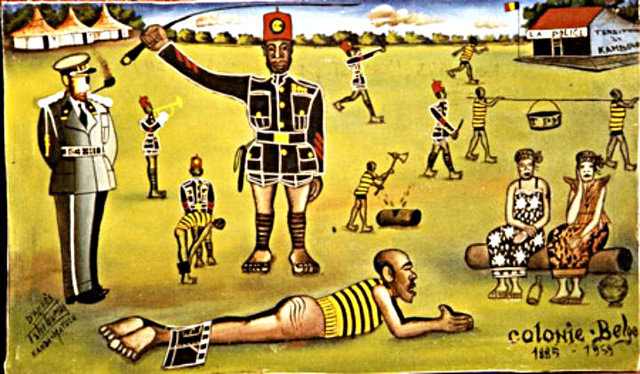

Historical context of the colonization of the Congo

Historical context of the colonization of the Congo

Capitalism and white supremacy, together the axes around which most of our contemporary existence has revolved, appear to have been dealt a rattling blow with the arrival of COVID-19. Maybe this is an unfashionably optimistic statement to make in the nascent tendency towards pessimism in the world in which we live, but a glance at recent events indicates the once unthinkable may have become possible.

Capitalism and white supremacy, together the axes around which most of our contemporary existence has revolved, appear to have been dealt a rattling blow with the arrival of COVID-19. Maybe this is an unfashionably optimistic statement to make in the nascent tendency towards pessimism in the world in which we live, but a glance at recent events indicates the once unthinkable may have become possible.

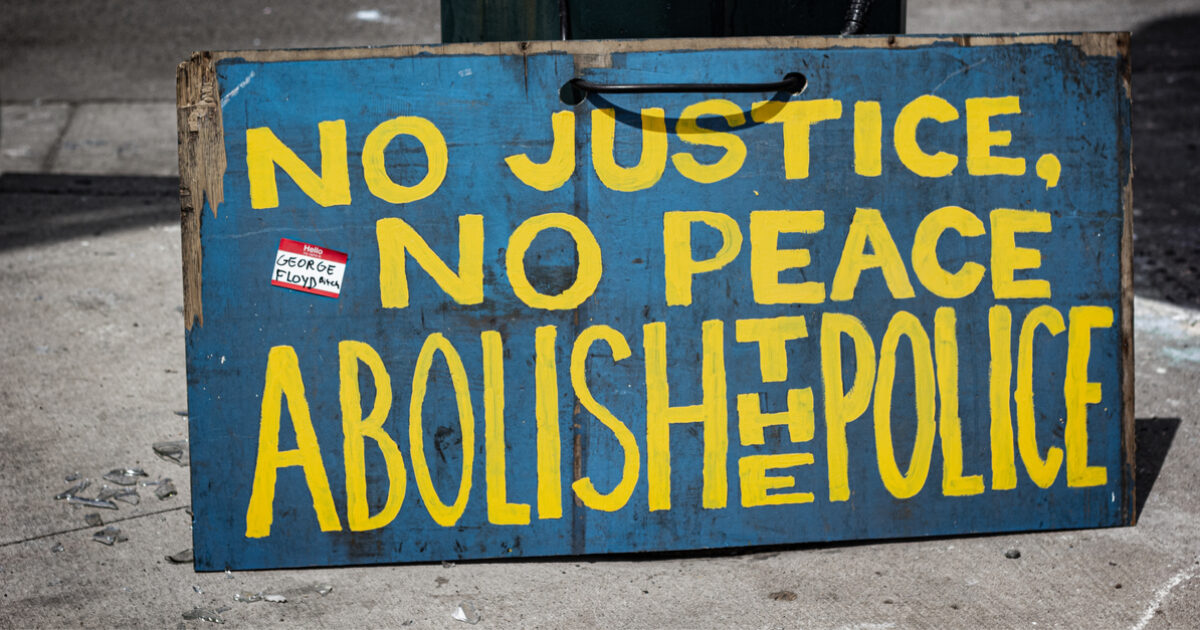

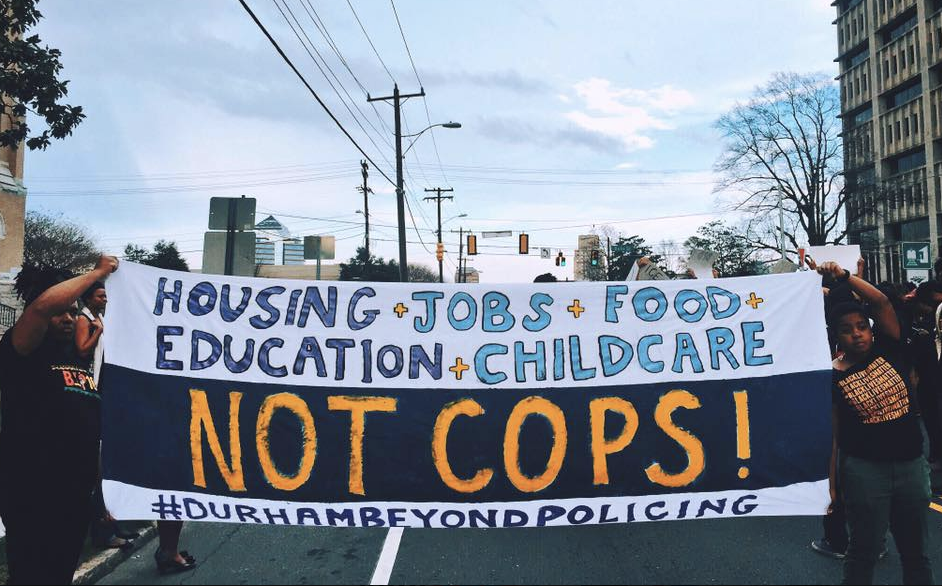

In recent days, with the spread of increasingly militant Black Lives Matter protests across all 50 U.S. states and beyond, it is little wonder that abolition of the police is a common demand from the left. For many it is clear why abolitionist politics are gaining traction, given that a recent poll showed 54 percent of the U.S. public supported the Minnesota protests and burning down of the local police precinct. The brutal murder of George Floyd was sadly just the latest in a long line of racist violence committed by the police but the protests that have been sparked by the murder have been historic in their scale. What’s perhaps not clear is what abolishing the police might look like in more concrete terms. In a world dominated by procedural police dramas and Hollywood cop heroics it is often difficult to imagine justice and security could be any other way.

In recent days, with the spread of increasingly militant Black Lives Matter protests across all 50 U.S. states and beyond, it is little wonder that abolition of the police is a common demand from the left. For many it is clear why abolitionist politics are gaining traction, given that a recent poll showed 54 percent of the U.S. public supported the Minnesota protests and burning down of the local police precinct. The brutal murder of George Floyd was sadly just the latest in a long line of racist violence committed by the police but the protests that have been sparked by the murder have been historic in their scale. What’s perhaps not clear is what abolishing the police might look like in more concrete terms. In a world dominated by procedural police dramas and Hollywood cop heroics it is often difficult to imagine justice and security could be any other way.

After 40 years of neo-liberal policies that uniquely punished Black communities, the rise of neo-fascist governments, and four centuries of forced servitude, theft and genocide, Black people around the world are once again rising up. The same corporations and military that uniquely harms Black people in the United States plays a role in repressing and killing Black people globally. Wherever you live, the police, the military, and men with guns serve to uphold hierarchies, preserve capital, and maintain various forms of oppression. We also know that patriarchal violence — whether it be at the hands of the state or individual people — continues to wreak havoc on the lives of Black people, especially women and LGBTQ people. Oftentimes, those first and most harmed are cis and trans women, children, and those regularly denied access to true safety.

After 40 years of neo-liberal policies that uniquely punished Black communities, the rise of neo-fascist governments, and four centuries of forced servitude, theft and genocide, Black people around the world are once again rising up. The same corporations and military that uniquely harms Black people in the United States plays a role in repressing and killing Black people globally. Wherever you live, the police, the military, and men with guns serve to uphold hierarchies, preserve capital, and maintain various forms of oppression. We also know that patriarchal violence — whether it be at the hands of the state or individual people — continues to wreak havoc on the lives of Black people, especially women and LGBTQ people. Oftentimes, those first and most harmed are cis and trans women, children, and those regularly denied access to true safety.

America has seen almost two weeks of protests against the murder of George Floyd. The anger and disappointment against this hate crime and a spate of others over the last few months are palpable. Floyd’s death appears to have sparked a civil rights movement the likes of which Americans have not seen in decades. Even mainstream media are acknowledging the need to address systemic and structural racism in this country.

America has seen almost two weeks of protests against the murder of George Floyd. The anger and disappointment against this hate crime and a spate of others over the last few months are palpable. Floyd’s death appears to have sparked a civil rights movement the likes of which Americans have not seen in decades. Even mainstream media are acknowledging the need to address systemic and structural racism in this country.

This article was written for L’Anticapitaliste, the weekly newspaper of the New Anticapitalist Party (NPA) of France.

This article was written for L’Anticapitaliste, the weekly newspaper of the New Anticapitalist Party (NPA) of France.

The passionate uprising that began in Minneapolis after police murdered George Floyd quickly spread

The passionate uprising that began in Minneapolis after police murdered George Floyd quickly spread

This spring, as some countries began to reopen after months of COVID-19 lockdowns, youthful rebellions broke out inside the two most powerful states in the world, the USA and China. The Black youth of Minneapolis, their allies, and countless others across the USA expressed their anger on the streets over yet another police murder, which was one too many. During the same days, the youth of Hong Kong renewed their protests against new anti-democratic moves by the Chinese government. The US protests, which grew into a massive nationwide Black Lives Matter uprising, also had a major international impact. In both cases, the USA and China, the youth did not flinch in the face of brutal police repression, inspiring their elders and many others around the world. These youth face a world of mass unemployment, precipitous economic inequality, and growing racial oppression fueled by right-wing populism, all of it worsened by COVID-19 and the economic meltdown.

This spring, as some countries began to reopen after months of COVID-19 lockdowns, youthful rebellions broke out inside the two most powerful states in the world, the USA and China. The Black youth of Minneapolis, their allies, and countless others across the USA expressed their anger on the streets over yet another police murder, which was one too many. During the same days, the youth of Hong Kong renewed their protests against new anti-democratic moves by the Chinese government. The US protests, which grew into a massive nationwide Black Lives Matter uprising, also had a major international impact. In both cases, the USA and China, the youth did not flinch in the face of brutal police repression, inspiring their elders and many others around the world. These youth face a world of mass unemployment, precipitous economic inequality, and growing racial oppression fueled by right-wing populism, all of it worsened by COVID-19 and the economic meltdown.

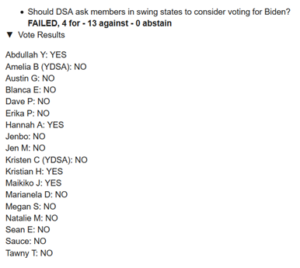

Every week, the Democratic Socialists of America (DSA)’s National leadership, the National Political Committee (NPC), posts a brief report of the votes they take at their meetings on the

Every week, the Democratic Socialists of America (DSA)’s National leadership, the National Political Committee (NPC), posts a brief report of the votes they take at their meetings on the

It takes but a few minutes for the ruling elite to recast collective calls for an end to state violence against blacks into images of criminality of black protestors and a call to end looting. How quickly the government wants us to get back to the status quo where the ruling elite has been looting from the working poor every single day of our lives. Looting from the labor of black workers over 200 years of slavery in our country. Looting from the labor of black workers in the 100 years of convict-leasing and forced contractual tenant-farming under the Black Codes. Robbing working people, and always the hardest hit black and brown people among them, their schools, their homes and communities, their labor, their health, their rights, and their lives. Even during the three months of this pandemic, a handful of billionaires have already looted $434 billion from the backs of the working people while people continue to suffer.

It takes but a few minutes for the ruling elite to recast collective calls for an end to state violence against blacks into images of criminality of black protestors and a call to end looting. How quickly the government wants us to get back to the status quo where the ruling elite has been looting from the working poor every single day of our lives. Looting from the labor of black workers over 200 years of slavery in our country. Looting from the labor of black workers in the 100 years of convict-leasing and forced contractual tenant-farming under the Black Codes. Robbing working people, and always the hardest hit black and brown people among them, their schools, their homes and communities, their labor, their health, their rights, and their lives. Even during the three months of this pandemic, a handful of billionaires have already looted $434 billion from the backs of the working people while people continue to suffer.

Part One of this article is

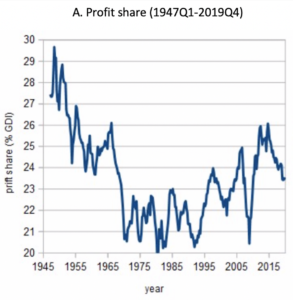

Part One of this article is  Figure 1: A. Profit share (net operating surplus as percent of gross domestic income), 1947-2019.

Figure 1: A. Profit share (net operating surplus as percent of gross domestic income), 1947-2019.

Criticizing labor is hard for socialists. On the one hand we know the unions are the underdog in the class struggle, and it’s painfully apparent that our society has suffered because unions are so weak. At the same time, it’s clear most unions can’t or won’t live up to their social and political obligations.

Criticizing labor is hard for socialists. On the one hand we know the unions are the underdog in the class struggle, and it’s painfully apparent that our society has suffered because unions are so weak. At the same time, it’s clear most unions can’t or won’t live up to their social and political obligations.

Amidst the backdrop of now

Amidst the backdrop of now