Detroiters demonstrate against the closing of a GM plant | Photo by Jim West

Many DSA members agree that the working class needs our own party. Not all are on board, but a lot. We debate how to get there: “Realign” (that is, reform) the Dems? A “dirty break,” where the goal is a new party but class-struggle candidates make use of the Democratic ballot line for now, while shunning the Democrats’ internal machinery? A few think we should be talking now about a Democratic Socialist Party, a “clean break.”

Some members speculate about a “party surrogate,” a membership organization that would function like a party without actually forming a new party, a strategy articulated most fully by Jared Abbott and Dustin Guastella. They urge us to be agnostic about whether a new, or different, party will come about through realignment or a dirty break. They argue correctly that a new party “will only have a realistic chance of electoral success if the insurgents have made sufficient inroads within one of the major parties — and a significant section of the labor movement — to attract a large portion of its supporters.”

They emphasize that the Democratic Party is “oligarchic and impenetrable” and discuss the “hyperconcentration of power in the hands of party and economic elites,” resulting in “increased party discipline, which in turn has dramatically raised the cost of internal party dissent.” They are clear that the Democratic Party is not set up to allow insurgencies and counsel against attempts at local takeovers. Yet they hold open the possibility that after sufficient organizing by the Left, “the establishment may abandon the party, effectively producing realignment.”

But I’d like to suggest that whether you have one foot in the realignment-is-possible camp or your eyes are firmly on the prize of workers’ own party makes a difference in how you organize and on what you’ll do at crucial forks in the road. The Democratic establishment will fight back. What is our plan when they do?

Here’s an analogy: Consider a union leader who accepts capitalism as the way things will always be. She takes for granted management rights in the union contract; in the best case scenario, the union tries to nibble away as best it can. When the employer asserts its right to close a plant, what can she do? The usual response is to negotiate a soft landing for laid-off workers, maybe to file a suit that will be thrown out by a judge who also believes capital’s rights are sacrosanct. It’s their plant, after all.

Then consider a union leader who doesn’t think the owners have the right to own, who’s for the overthrow of capitalism. Yes, both leaders are constrained by members’ fears, by the laws, by capitalists’ actual power regardless of their right to that power, by all sorts of handcuffs. But the difference in outlook will color everything the two leaders do, from the shop floor up. A Marxist outlook produces different approaches to countless daily practical decisions as well as to big political strategy; the difference is not just far away and abstract.

Consider a real-life plant closing scenario. General Motors announced in November 2018 that it would shut its Poletown plant in Detroit. Local and national United Auto Workers officials barely peeped, and even shut down a Poletown member’s motion to create a fight-back committee (he was also a DSA member). Detroit DSA, not constrained by allegiance to GM’s profits, showed what class-struggle unionists might do, mounting a campaign, backed by Rep. Rashida Tlaib, to demand the city government take the plant over through eminent domain and use it for green manufacturing.

POLITICS MAKES THE DIFFERENCE

The contrast between the two outlooks is clear in Toni Gilpin’s The Long Deep Grudge, new this year, about the Farm Equipment Workers union, the FE. (Gilpin is a DSA member in the Chicago chapter.) Gilpin shows how the socialist politics of FE leaders played out in practice, greatly to the benefit of FE members.

The FE represented workers in the agricultural implement industry from 1938 to 1955, when it was forced by McCarthyism to merge with its rival, the UAW. FE leaders, though they didn’t openly say so, were “profoundly influenced” by the Communist Party. That refusal to be overawed by the rights of capital made for a union that was significantly different from most others of its era.

Gilpin details how UAW officials, who backed McCarthyite purges of CP-affiliated labor leaders, bought the notion that increasing productivity (i.e., speedup) would produce a bigger pie for owners and workers to share. The UAW’s Walter Reuther signed a National Planning Association code that said union leaders should promote “employee practices which will increase productivity and improve the competitive position of the company.”

The FE, in contrast, resisted productivity pay and long contracts (long contracts meant fewer opportunities to fight the boss for a better one). “Through their Marxist lens,” says Gilpin, “they saw wage levels not as reflective of ‘objective’ realities but of relative power, and they maintained a conviction that profit, in fact, did represent the surplus value extracted from the workforce. For the FE leadership, the equation remained simple and unchanging: for workers to enjoy more, the corporations and the people who controlled them must get less.”

Between 1945 and 1954 International Harvester plants represented by the FE saw more than 1,000 work stoppages, compared to 200 at UAW IH plants. (Two hundred is still an astonishing number by today’s standards.) One reason was the high ratio of stewards to workers, about one to every 35 or 40. IH officials complained that these stewards continually tried to “promote unrest, stir up ill will, harass the company, and convince as many members as it can that labor relations with Harvester is and must be class warfare.” Damn straight.

The FE was also unusual in its insistence on complete equality at International Harvester’s Louisville, Kentucky local, where Black members were 15 percent of the membership. A united Louisville local won a 42-day strike against IH’s “Southern differential” — a third-tier pay scale in a city where most considered Black or white workers lucky to have such a job.

Famed civil rights activist Anne Braden, who lived in Louisville, said of the Harvester workers, “People really enjoyed getting up and going to work in the morning” because of the FE. “You knew there was going to be something interesting at the gate, there was going to be a leaflet, there was going to be people out about something, and there was a real esprit de corps that I think made it bearable to go to work.” Gilpin says the “fierce and sustained loyalty of the FE’s rank and file” was the result of “the precepts of proper trade unionism” as practiced by its socialist leaders.

As a former UAW member at GM and Chrysler, and as one who covered the UAW for decades at Labor Notes, I can also personally testify to the difference. When I was at GM in 1976 the shop committee instigated one of those wildcat strikes so rare today; the whole plant was down. Agreeing with management that stopping production was the worst of sins, the UAW International agreed to let management fire 10 rank and filers with no recourse to the grievance procedure. The letter informing me was signed by an international rep. “Dear Sister Slaughter…”

OUR PARTY AND THEIRS

What’s the connection to electoral politics as practiced by DSA members? It’s that idea of a guiding star — basing our practice on where we want to go.

Yes, it’s theoretically possible to imagine there being so many insurgents inside the Democratic Party that its bosses would leave (about as possible as imagining Trump will resign). But it is on the proponents of realignment and those who take a wait-and-see approach to explain why the world’s most powerful capitalist class would decide to give up control of one of its most powerful tools. Short of a breakdown of the state itself, in what situation would capitalists actually do this? Would the owners of GM just decide one day to abandon the company to members of the UAW? These both strike me as unrealistic scenarios.

If you think it is possible capitalists would abandon the Democratic Party under less extreme circumstances (how?), your guiding star is likely to become an internal takeover. Hey, turns out it’s easy to become a precinct delegate! Isn’t this what the Tea Party did? It worked for the Republicans. If we can get on Committee X we can change Rule Y, which will help Candidate Z. All this time we’re interfacing with party elites and their loyal activists, rather than with members of the working class we might win over.

And if you think that in the future the Democratic Party is going to become our party, your campaign speeches will tend toward “we have to improve this party which has a glorious history of fighting for workers and the poor” rather than “we need our own party; this one is owned by the machinery of capitalism.”

The wait-and-see approach rightly advocates that the Left build enough power to threaten the Democratic Party elites, but what then? Surely they will fight back before we’re strong enough to oust them; they already are. Think about how quickly Joe Biden became this year’s presidential nominee. If we’re doing our jobs, things will only escalate from here. Without a plan for forming a new party, and a base we’ve spent time organizing towards it, our forces will be thrown into disarray by the establishment’s attacks, right at the moment we should be most organized.

When we’ve built that power all of us agree we want, what happens when we come to the next fork in the road — say when a much larger labor movement and all the social movements have backed the next Bernie but the Democratic bosses have stolen the nomination? We don’t want to be shilly-shallying over “shall we stay or shall we go?” all over again.

Far better for us to decide from the start that our goal is workers’ own party, because that will color everything we do on our way there.

First published in The Call.

This article was written for L’Anticapitaliste, the weekly newspaper of the New Anticapitalist Party (NPA) of France.

This article was written for L’Anticapitaliste, the weekly newspaper of the New Anticapitalist Party (NPA) of France.

The Whitney Museum recently took down our murals. True enough, they never asked us to paint on the plywood barrier built to protect the building during the recent protests. But for a few nights we painted. Mine was a mural about police brutality toward protestors. Now the Whitney has taken them all down.

The Whitney Museum recently took down our murals. True enough, they never asked us to paint on the plywood barrier built to protect the building during the recent protests. But for a few nights we painted. Mine was a mural about police brutality toward protestors. Now the Whitney has taken them all down. I was thinking about the clearing out of Lafayette square, the tear gas and violence used on peaceful protesters. And I thought about my own recent experience at a demonstration here in New York at Columbus Circle. I was painting from those memories and feelings.

I was thinking about the clearing out of Lafayette square, the tear gas and violence used on peaceful protesters. And I thought about my own recent experience at a demonstration here in New York at Columbus Circle. I was painting from those memories and feelings.

Ciudad Juarez has a long history of crises – foreign invasions, revolutions, economic recessions tied to the United States, the 9-11 border constriction and transnational gangland wars. Then there’s the perpetual crisis of putting food on the table in a high-priced, low-wage city while staying safe in a place where violence can surge at any moment.

Ciudad Juarez has a long history of crises – foreign invasions, revolutions, economic recessions tied to the United States, the 9-11 border constriction and transnational gangland wars. Then there’s the perpetual crisis of putting food on the table in a high-priced, low-wage city while staying safe in a place where violence can surge at any moment.

This article was written for L’Anticapitaliste, the weekly newspaper of the New Anticapitalist Party (NPA) of France.

This article was written for L’Anticapitaliste, the weekly newspaper of the New Anticapitalist Party (NPA) of France.

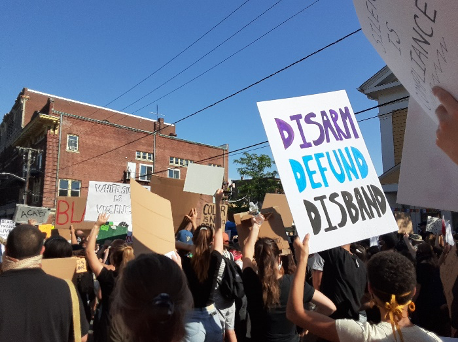

What is new is that today’s protests have been more militant and have spread more rapidly than those that occurred at the height of the Black Lives Matter movement, and they are occurring in defiance of curfews and stay-in-place orders imposed by mayors and governors. Today’s protests appear to be more multiracial, although most are decisively being led by young Black people and not by any existing organizations. What’s more, police repression has failed to dampen the turnout or win public sympathy. Instead, the protests are widely seen as justified, with one Reuters poll showing 64 percent of Americans support them.14 If the previous upsurge of anti-racist struggle helped expose the systemic racism of policing and the criminal “justice” system, then today’s protests are delegitimizing the economic and political actors who enable and abet those systems. After all, when the government responds this quickly to quell mass protest but cannot find the will or resources to fight a mass pandemic, it is clear that our health and safety are not its priority.

What is new is that today’s protests have been more militant and have spread more rapidly than those that occurred at the height of the Black Lives Matter movement, and they are occurring in defiance of curfews and stay-in-place orders imposed by mayors and governors. Today’s protests appear to be more multiracial, although most are decisively being led by young Black people and not by any existing organizations. What’s more, police repression has failed to dampen the turnout or win public sympathy. Instead, the protests are widely seen as justified, with one Reuters poll showing 64 percent of Americans support them.14 If the previous upsurge of anti-racist struggle helped expose the systemic racism of policing and the criminal “justice” system, then today’s protests are delegitimizing the economic and political actors who enable and abet those systems. After all, when the government responds this quickly to quell mass protest but cannot find the will or resources to fight a mass pandemic, it is clear that our health and safety are not its priority.

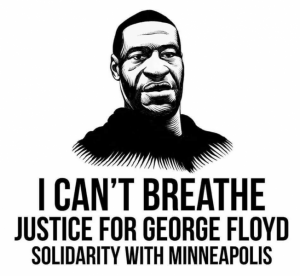

Claudia Rankine’s provocative and polyphonic work, Citizen: An American Lyric, has spurred much-needed conversations around race and racism both in academia as well as in more informal discourse. In the wake of the recent protests following the death of George Floyd at the hands of a Minneapolis police officer, this book—winner of the National Book Critics Circle Award for Poetry and the PEN Open Book Award—finds itself all the more relevant and also unnervingly prescient. Black Americans, to this day, Rankine reminds us, continue to be sidelined and deprived through residential isolation and through diminished access to housing, education, healthcare, and structural facilities. They are regularly subjected to racism and colorism, at times when they least expect to be—while driving to work, taking the subway, meeting a real-estate agent, or visiting a therapist, among other mundane routines—and such prejudices can be confounding, destabilizing, and painfully hard to make sense of. These violations settle in black bodies and are passed on as generational trauma, a trauma largely repressed but occasionally finding vent as hurt, embarrassment, horror, and rage, the kind now sweeping America.

Claudia Rankine’s provocative and polyphonic work, Citizen: An American Lyric, has spurred much-needed conversations around race and racism both in academia as well as in more informal discourse. In the wake of the recent protests following the death of George Floyd at the hands of a Minneapolis police officer, this book—winner of the National Book Critics Circle Award for Poetry and the PEN Open Book Award—finds itself all the more relevant and also unnervingly prescient. Black Americans, to this day, Rankine reminds us, continue to be sidelined and deprived through residential isolation and through diminished access to housing, education, healthcare, and structural facilities. They are regularly subjected to racism and colorism, at times when they least expect to be—while driving to work, taking the subway, meeting a real-estate agent, or visiting a therapist, among other mundane routines—and such prejudices can be confounding, destabilizing, and painfully hard to make sense of. These violations settle in black bodies and are passed on as generational trauma, a trauma largely repressed but occasionally finding vent as hurt, embarrassment, horror, and rage, the kind now sweeping America.

On April 9, the day after Bernie Sanders announced he would suspend his campaign for the U.S. presidency, the newly formed Greater Lafayette Indiana chapter of Democratic Socialists of America (DSA) held its biweekly Zoom meeting. The chapter had come to life in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic, made up of long-time local radicals and activists, and an upstart contingent of college students who had built a vital and dynamic YDSA (Young DSA) on the local college campus. The Zoom call that night was dedicated mainly to figuring out how to raise money to buy plastic bottles for an environmentally safe hand sanitizer created by one of the members. The plan was to distribute the bottles in public places to raise consciousness and public health standards during the pandemic. No one on the call talked at all about Sanders’ withdrawal, except to note that the local student group backing Sanders had decided in the wake of his campaign suspension to cast its support for the new YDSA group.

On April 9, the day after Bernie Sanders announced he would suspend his campaign for the U.S. presidency, the newly formed Greater Lafayette Indiana chapter of Democratic Socialists of America (DSA) held its biweekly Zoom meeting. The chapter had come to life in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic, made up of long-time local radicals and activists, and an upstart contingent of college students who had built a vital and dynamic YDSA (Young DSA) on the local college campus. The Zoom call that night was dedicated mainly to figuring out how to raise money to buy plastic bottles for an environmentally safe hand sanitizer created by one of the members. The plan was to distribute the bottles in public places to raise consciousness and public health standards during the pandemic. No one on the call talked at all about Sanders’ withdrawal, except to note that the local student group backing Sanders had decided in the wake of his campaign suspension to cast its support for the new YDSA group.

This article was written for L’Anticapitaliste, the weekly newspaper of the New Anticapitalist Party (NPA) of France.

This article was written for L’Anticapitaliste, the weekly newspaper of the New Anticapitalist Party (NPA) of France.

The rituals of the political left are as predictable as they are puzzling. It’s an election year, so we leftists have a sworn duty to reignite, for the 10,000th time, the debate about “lesser-evil voting.” Glenn Greenwald recently made some comments on the matter, as did Noam Chomsky, and Bruce Levine weighed in in a

The rituals of the political left are as predictable as they are puzzling. It’s an election year, so we leftists have a sworn duty to reignite, for the 10,000th time, the debate about “lesser-evil voting.” Glenn Greenwald recently made some comments on the matter, as did Noam Chomsky, and Bruce Levine weighed in in a

The Black-led multiracial working-class uprising has radically changed US and global politics. It has become the outlet for all the rage built up by years of racist police violence, institutional racism, and the impoverishment of working people. These mass militant protests, which have swept through big cities and small towns in every corner of the country and stirred similar actions throughout the world, have won

The Black-led multiracial working-class uprising has radically changed US and global politics. It has become the outlet for all the rage built up by years of racist police violence, institutional racism, and the impoverishment of working people. These mass militant protests, which have swept through big cities and small towns in every corner of the country and stirred similar actions throughout the world, have won

This article was written for L’Anticapitaliste, the weekly newspaper of the New Anticapitalist Party (NPA) of France.

This article was written for L’Anticapitaliste, the weekly newspaper of the New Anticapitalist Party (NPA) of France.