[from New Politics, vol. 6, no. 1 (new series), whole no. 21, Summer 1996]

[from New Politics, vol. 6, no. 1 (new series), whole no. 21, Summer 1996]

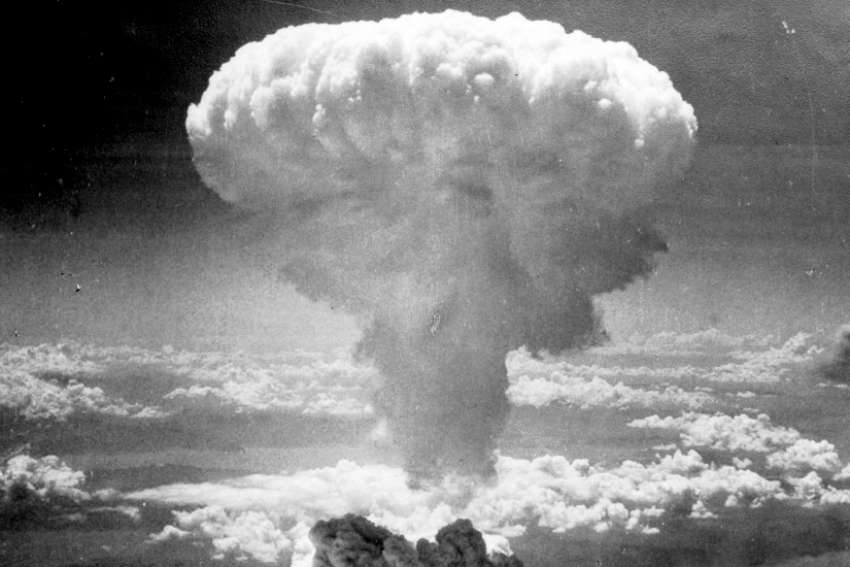

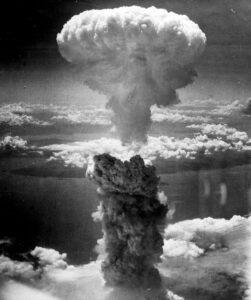

[Editors’ Note: The review essay below, originally published in New Politics in 1996, provides a critique of the decision to drop an atomic bomb on the Japanese city of Hiroshima during World War II. Though there has been much additional historical evidence made available since the essay was written, its discussion of the moral and political issues remains relevant today.

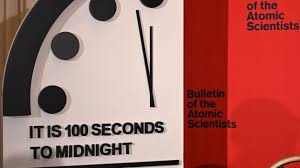

The essay was first published at a time when it seemed like the danger of nuclear war was receding. Since 1947, the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists has been regularly reporting the time on its Doomsday Clock – how close are we to civilizational destruction through nuclear war or climate catastrophe? Beginning at 7 minutes to midnight, it got as close as 2 minutes to midnight in 1953 (as the United States and the Soviet Union added hydrogen weapons to their arsenals) and as far away as 17 minutes to midnight in 1991. But the clock ticked closer to apocalypse: 9 minutes from midnight in 1998 (as Pakistan and India tested nuclear weapons), 7 minutes in 2002 (as the U.S. withdrew from the ABM treaty), 5 minutes in 2007 (as North Korea conducted a nuclear test). In 2010, the clock was pushed back to 6 minutes, as U.S.-Russian nuclear talks began, as well as some modest climate mitigation measures. But by 2016 it had moved to within 3 minutes to midnight, as nuclear force modernization was pursued by Washington and Moscow. Then, the clock moved to 2.5 minutes from midnight in 2017, and to 2 minutes to midnight in 2018 and 2019 as Trump withdrew from the Iran nuclear deal and from the INF agreement, as both the United States and Russia have been racing to develop long-banned weapons, and as Trump indicated he would not extend the agreement limiting U.S. and Russian strategic nuclear weapons. Then this past January, the Atomic Scientists reported:

“In the nuclear realm, national leaders have ended or undermined several major arms control treaties and negotiations during the last year, creating an environment conducive to a renewed nuclear arms race, to the proliferation of nuclear weapons, and to lowered barriers to nuclear war. Political conflicts regarding nuclear programs in Iran and North Korea remain unresolved and are, if anything, worsening. US-Russia cooperation on arms control and disarmament is all but nonexistent.”

And the clock was moved to 100 seconds from midnight, the closest it has ever been.

In May, the Trump administration considered resuming nuclear testing, backing off on June 24, reassuring no one as it declared

“We made very clear, as we have from the moment we adopted a testing moratorium in 1992, that we maintain and will maintain the ability to conduct nuclear tests if we see any reason to do so, whatever that reason may be. But that said, I am unaware of any particular reason to test at this stage.”

In August 2017, Trump warned North Korea that it “best not make any more threats to the United States … They will be met with fire and fury like the world has never seen” – a nuclear first strike threat echoing Truman’s threat to Japan after Hiroshima (“If they do not now accept our terms they may expect a rain of ruin from the air, the like of which has never been seen on this earth”).

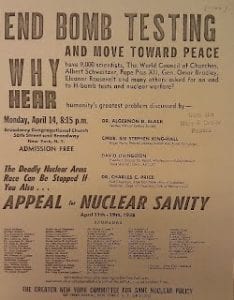

Seventy-five years into the nuclear age, the danger we face is horrendous and unacceptable. As the Doomsday Clock ticks ever closer to midnight, we must demand a world without nuclear weapons and emphasize their moral unacceptability.]

Books Discussed in this Article

• Thomas B. Allen and Norman Polmar, Code-Name Downfall, New York: Simon & Schuster, 1995.

• Gar Alperovitz, et al., The Decision To Use the Atomic Bomb and the Architecture of an American Myth, New York: Knopf, 1995.

• Robert Jay Lifton and Greg Mitchell, Hiroshima in America: Fifty Years of Denial, New York: G. P. Putnam, 1995.

• Robert James Maddox, Weapons for Victory: The Hiroshima Decision Fifty Years Later, Columbia: Univ. of Missouri Press, 1995.

• Ronald Takaki, Hiroshima: Why America Dropped the Bomb, Boston: Little, Brown, 1995.

• “Hiroshima in History and Memory: A Symposium,” in Diplomatic History, vol. 19, no. 2, Spring 1995.

The fiftieth anniversary of the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki elicited an outpouring of books and articles and evoked passionate debate, as well it might given the profound moral and political issues involved.

Most discussions of Hiroshima, unfortunately, treat the bomb in isolation from a broader assessment of the war in the Pacific. All too often, there is an unstated assumption that the war represented a clash between absolute good and absolute evil, and the question of the bomb is reduced to one of means and ends: was it proper to use this horrible weapon for noble ends? A less one-sided view of the war, on the other hand, provides a rather different context within which to evaluate the dropping of the bomb.

To a considerable extent the Pacific War was a war between colonial powers. The United States did not get involved until military bases on three of its colonial territories — Hawaii, the Philippines, and Guam — were attacked by the Japanese. Britain was drawn in by the attack on its colonies of Malaya, Singapore, and Hong Kong. And the Dutch declared war on Japan in anticipation of the assault on their colony, the Netherlands East Indies (Indonesia). Before Pearl Harbor, Washington tightened its economic sanctions on Japan when the latter moved into northern Indochina in September 1940, and southern Indochina in July 1941 — that is, when Tokyo encroached on the colonial domains of Vichy France. As Britain’s First Sea Lord had earlier privately acknowledged, the western powers had “got most of the world already, or the best parts of it” and they sought to “prevent others taking it away.”1

In much of Asia there was considerable sympathy for Japan’s ousting of the western colonialists. A nationalist leader in the East Indies acknowledged that a majority of his compatriots “rejoiced over Japanese victories.” Even Nehru told Edgar Snow privately of his emotional sympathy for Japan (Thorne, pp. 6, 154, 156 ).

China was the main independent country victimized by Japanese aggression, but that aggression had been going on for ten years before Pearl Harbor with great brutality, though evoking little reaction from Washington and London. Indeed, the chief protests from the United States and Britain related to Japanese interference with their “rights” in China, rights that made a mockery of Chinese independence in the first place. Among these rights were extraterritoriality, the administration of an “International Settlement” at Shanghai, control of Chinese maritime customs, and the right to deploy military forces within China’s territory. When Japan invaded China in 1937, for example, Washington had more than 2,000 troops ashore and another 1,800 on its 13 naval vessels that patrolled Chinese waters. In U.S.-Japanese talks it was the issue of “the treatment of American business in China” that “engaged as much of the time of the negotiators as any other,” in the words of mainstream diplomat and historian Herbert Feis.2

The Pacific War had its roots in the Great Depression. The colonial powers had responded to the economic crisis by imposing high protective tariffs around their empires, to the benefit of their own firms. Washington placed the huge U.S. market behind the Smoot-Hawley tariff and maintained special preferences for its own business interests in the Philippines and Cuba. “All over the world,” a State Department official noted, “various obstacles to the free and natural flow of Japanese exports” had been raised.3 Given this situation, it is not surprising that Japan sought to emulate the other colonial powers and establish a self-sufficient economic empire of its own, which meant expansion into China. To U.S. officials, the United States was entitled to its Monroe Doctrine for Latin America, but the Japanese could not have their Monroe Doctrine for Asia. This inevitably led to a clash between Tokyo and Washington, but it was a war not for freedom, but to determine who would dominate Asia.

The goals of the war were clearly revealed at the fighting’s end. The United States took over a vast network of Pacific islands as strategic bases without the consent of their inhabitants. Washington granted independence to the Philippines, but maintained U.S. economic and military privileges there, while restoring the pre-war elite to power. The British, using Japanese troops and U.S. weapons, secured Indonesia for the Netherlands and Vietnam for the French. In the south of Korea, U.S. troops installed a reactionary and corrupt dictatorship. And in China, Washington intervened in the civil war, providing massive military and economic aid to Chiang Kai-shek and deploying 50,000 marines to hold key communication and transportation routes while Chiang consolidated his hold.4 Washington, of course, was not omnipotent, and it was unable to impose its will everywhere. But throughout Asia, the U.S. victory in World War II meant that Washington replaced Tokyo as the dominant power. And it was this war, not some abstract pure moral crusade, during which Hiroshima and Nagasaki were obliterated.

Historians and the Bomb

Over the past fifty years, much documentation has become available relating to the historical question — why did the United States government drop the bombs? — which bears on, but is logically distinct from, the moral/political question — was dropping the bombs justified?

In 1965 Gar Alperovitz wrote Atomic Diplomacy, the first full-length study to advance the thesis that the bombs were dropped in order to intimidate the Soviet Union. Now, together with a team of researchers, he has written The Decision To Use the Atomic Bomb, in which he argues that the modern evidence not only sustains but reinforces his position. He provides a vast amount of documentation; at some crucial points in his argument, however, the evidence seems less definitive than he rather insistently suggests.

That U.S. policy makers saw a benefit vis-a-vis the Soviet Union from using the bomb has now been widely accepted, but that relations with Moscow constituted the reason for obliterating Hiroshima and Nagasaki is still much disputed, even on the left. Over the years in numerous articles, and most recently in a symposium in the journal Diplomatic History (hereafter DH), Barton J. Bernstein has argued that the atomic bombings were “over-determined,” that U.S. officials welcomed the opportunity to intimidate Moscow by using the bomb, but they would have used it even if the Soviet Union didn’t exist.

The traditional view — that of the U.S. officials responsible for the bombing and of their supporters — is that the bomb was used for no other reason than to hasten the end of the war and save American lives, and it was fully justified. Robert James Maddox, who two decades ago challenged the academic integrity of New Left historians, including Alperovitz (though his own use of evidence left much to be desired), has now written Weapons for Victory, a defense of the bomb and an often vituperative attack on its critics. In Code-Name Downfall, two military historians, Thomas B. Allen and Norman Polmar, describe the planned invasion of Japan and conclude that the bomb was justified to forestall the bloodletting that such an invasion would have entailed.

Robert Jay Lifton and Greg Mitchell have written a wide-ranging book, Hiroshima in America, providing a wealth of information, not so much on the decision to use the bomb, but on the response to that decision over the past half century. Ronald Takaki’s volume, Hiroshima, starts off accepting the Alperovitz thesis, and thus doesn’t help us evaluate it, but his information on the context of racism within which U.S. decision-making took place is useful.

Aside from the question of why U.S. leaders used the bomb, there are other historical controversies: for example, why did Japanese leaders surrender when they did and would they have done so in the absence of the bomb? These are interesting and significant questions, but it is important to see that these are not directly relevant to answering either the moral/political question of the bomb’s justification or the historical question of why the bomb was dropped.

Consider a recent comment by Ian Buruma:

Alperovitz’s case that the bomb was not dropped to prevent a final bloody battle rests entirely on the assumption that Truman and his advisers knew perfectly well that the Japanese were on the verge of capitulation before the destruction of Hiroshima. Closer examination of what went on in Tokyo shows that the Japanese were not.5

But what went on in Tokyo is strictly irrelevant to what Truman and his advisers knew (or, more accurately, what they believed). Suppose I break into the house of a total stranger, go up to his bedroom, and blow his brains out. The stranger’s diary is later discovered and it shows that he was intending to commit a murder the next day. Obviously, this subsequent discovery does not alter our moral judgment of my action or our understanding of why I did what I did. Likewise, suppose Truman believed that the Japanese were prepared to surrender but decided to drop the bombs anyway. If Buruma is correct that Japanese leaders were not in fact prepared to surrender (a matter to which we will later return), this has no bearing on our moral judgment of Truman’s action nor on our understanding of why he did it.6

Killing Civilians

A good place to start thinking about the moral issues involved in the atomic bombing is with this description of the Japanese attack on Hong Kong from Allen and Polmar (p. 158):

To force the surrender of Fort Stanley in Hong Kong in December 1941, Japanese troops began torturing British and Chinese captives, cutting off ears and fingers, cutting out tongues, and gouging eyes before killing the victims by dismemberment. British and Chinese nurses were tied down on corpses and raped, then bayoneted to death. The captors allowed some witnesses to escape and report the atrocities. Fort Stanley surrendered.

We are naturally nauseated by this behavior. But why? Presumably there are some Japanese apologists who would be only too glad to point out that the number of civilians raped and butchered to induce surrender was less than the number of Japanese soldiers who might have died in an assault on the fort. Nevertheless, Allen and Polmar expect us to be repelled by the Japanese action and rightly so, because there is a moral distinction between civilians and combatants. But nowhere in their book on why “the atom bomb had to be dropped” (to quote their subtitle) do they ever apply this same moral standard to U.S. behavior.

Of course, the dropping of the atomic bombs was not the first U.S. action to fail to distinguish between combatants and civilians. U.S. warplanes had already incinerated hundreds of thousands of Japanese civilians, and not as the incidental byproduct of destroying military targets, but intentionally. Maddox (p. 120) quotes White House chief of staff Admiral William D. Leahy’s dissent from the use of the atomic bomb “Wars cannot be won by destroying women and children.” To which Maddox comments, “How he thought women and children would have fared had LeMay [the commander of the fire-bombing raids] gone on for months driving them back to the stone age’ he did not say.” Maddox is quite right to point out Leahy’s moral hypocrisy, but Maddox does not conclude that both the conventional and atomic bombings were immoral; instead he considers both justified. There are two compelling indications, however, that even U.S. officials didn’t believe their conventional terror bombing could be justified: First, they had vigorously denounced earlier air attacks on civilians by the Japanese as breaches of basic standards of morality and international law, and, second, they made efforts to disguise their actions as aimed at military targets when in fact they were not.

Truman’s Secretary of State, James F. Byrnes, was one among many who has argued that while there were many casualties from the atomic bombs, these were “not nearly so many as there would have been had our air force continued to drop incendiary bombs on Japan’s cities.”7 Allen and Polmar add to this argument by suggesting that without the atomic bomb, not only would the United States have continued its conventional fire raids, but quite possibly it would have resorted to other “horror weapons” as well: gas warfare, biological attacks on rice fields, and V-1 missiles (pp. 173-191, 256, 293, 93). This argument for using the atomic bomb, however, was well answered by Michael Walzer almost twenty years ago: it is one thing to say I must do a horrible thing in order to prevent someone from doing something even more horrible (a plausible argument); it is quite another to say I must do a horrible thing or else I will do something even more horrible. In Walzer’s words, “Our purpose, then, was not to avert a butchery’ that someone else was threatening, but one that we were threatening, and had already begun to carry out.”8

The Invasion

Some argue that the absolute moral prohibition against the killing of civilians cannot be sustained under conditions of modern warfare. According to this view it is permissible to kill some enemy civilians if a large number of one’s soldiers can thereby be saved. After all, conscripts are often no less “innocent” victims than civilians, and civilians frequently work to support their country’s military effort. If we were to accept this view, however, surely numbers would matter: that is, the number of lives saved and the number of civilians killed. U.S. policy makers understood the importance of the numbers, and that’s why they claimed such inflated figures for the expected U.S. casualties in an invasion. Maddox says these later exaggerations — if such they were — are perfectly understandable if not admirable, but tell us nothing about the thinking at the time of Truman and others. On the contrary, however, the misrepresentations indicate that U.S. officials themselves knew that the bombings could not be morally justified unless they led to some huge saving of lives. Truman would have used the bombs, says Maddox, even to save only 10,000 U.S. lives. That may be, but the question remains whether that would have been justified, and Truman’s fabrications suggest that he knew the answer was no.

Covering all his bases, Maddox argues that the claims by Truman and others may not have been exaggerated at all, but his argument is extremely slippery. The only official casualty prediction known to have been seen by Truman was a June 18, 1945, estimate of 31,000 casualties (and thus deaths of about a fifth that number) in the first 30 days of an invasion of the Japanese home island of Kyushu scheduled for November 1, 1945. Military planners estimated that the full Kyushu campaign and an invasion of the Tokyo plain the following Spring (which they didn’t believe would be necessary) would cost some 40,000 U.S. lives. However, an unanticipated Japanese buildup after mid-June, says Maddox, makes these figures worthless, and those who cite them “either remain unaware of the literature on the subject, in which case they are incompetent to write about it, or they know the figures had become meaningless but nonetheless continue to employ them to promote their own agendas” (p. 4). Truman claimed in his memoirs that U.S. deaths would be half a million, and this figure, says Maddox, did not come out of thin air. Then he cites an August 1944 Joint Chiefs of Staff study, which he says “never was officially revised.” But of course it was revised: that is what the estimates developed 10 months later were, after Japan’s military situation had drastically deteriorated and a detailed invasion plan had been worked out. In May 1945, former president Herbert Hoover wrote to Truman, urging a clarification of surrender terms in order to avoid the loss of half a million to a million lives. Hoover, of course, had no access to military planning documents, but his letter was passed on to the War Department for review. The resulting analysis, Maddox says, found Hoover’s estimate “too high” (it actually found it ” entirely too high'” Alperovitz, p. 521). So while denouncing those who rely on an allegedly out-of-date June 18, 1945, estimate as being incompetent or worse, Maddox himself relies on earlier, and surely less authoritative figures.

At Potsdam in July, General Marshall told other military leaders that there were 500,000 Japanese troops on Kyushu, more than earlier estimates showed. Maddox writes (p. 118) that “It is inconceivable that he failed to inform Truman about the Japanese buildup when they met the next day to discuss the tactical and political situation.'” That meeting, which took at most 35 minutes, was described in full as follows by Truman in his diary: “At 10:15 I had Gen. Marshall come in and discuss with me the tactical and political situation. He is a level headed man so is Mountbatten.”9 Given Truman’s concern about U.S. casualties, if Marshall now told him that an invasion that was thought would cost 40,000 deaths would now cost 500,000 deaths — 70% more U.S. combat deaths than in all the rest of World War II — one would think the president might have been moved to record something more. Indeed, it is inconceivable that Truman or Marshall would ever have authorized an operation they expected would involve half a million U.S. deaths.

An alleged meeting at Potsdam is also the source for another exaggerated casualty estimate. In a 1953 letter to an Army historian, Truman wrote that after receiving word of the successful test of the atom bomb at Alamogordo, he called together his top advisers:

I asked General Marshall what it would cost in lives to land on the Tokio [sic] plain and other places in Japan. It was his opinion that such an invasion would cost at a minimum one quarter of a million casualties, and might cost as much as a million, on the American side alone, with an equal number of the enemy. The other military and naval men present agreed.10

Allen and Polmar (pp. 266-67, 329n) take this account seriously, but there are a number of problems with it. First, there is no evidence that such a meeting ever took place: it is referred to in no official record of the conference or any of the many contemporaneous diaries (Alperovitz, p. 518). Second, we know that Truman’s first draft of his 1953 letter used the figure of 250,000 casualties and that he was advised by an aide that his figure was lower than one offered by former secretary of war Stimson and, though Truman’s recollection sounded “more reasonable than Stimson’s,” in order to avoid a conflict he ought to change it to read 250,000 to a million (Alperovitz, pp. 517-18). Third, the rest of Truman’s letter includes the claim that at this same meeting he asked Stimson which cities in Japan were devoted “exclusively to war production,” a request that if actually made would have sent his advisers into fits of laughter. And fourth, even if the account in Truman’s letter is true, his original figure of 250,000 casualties corresponds to a death toll of about 50,000, which is about one tenth of the “half a million lives” Truman mentions in his memoirs.11

Defenders of the bomb have produced all sorts of other evidence to support higher casualty estimates for the invasion of Japan; none of it, however, is very convincing.12

Maddox writes (p. 60) that “Perhaps only an intellectual could assert that 193,500 anticipated casualties were too insignificant to have caused Truman to use atomic bombs.” Obviously, such casualties, and 40,000 deaths, are profoundly significant. But does their moral significance override that of the 200,000 deaths in Hiroshima and Nagasaki? Most of these deaths were of civilians, including many conscripted Korean laborers.13 Maddox thinks only an intellectual would have qualms about this moral trade-off, but Truman and other officials knew that many Americans would find it unsettling. And thus, they exaggerated not only the invasion costs, but also the military importance of the target cities, claiming falsely that the latter were “devoted almost exclusively to the manufacture of ammunition and weapons of destruction” (Lifton & Mitchell, p. 172, citing Dec. 12, 1946 Truman letter).14

Saving Civilians?

A more subtle defense of the bomb is the claim that even without intentional attacks on civilians, more Japanese civilians might have died in a last ditch defense against invasion than died at Hiroshima and Nagasaki. After all, some hundred and fifty thousand civilians died on Okinawa though there was no specific U.S. effort to target them. If the bomb actually saved the lives of many civilians, then its use might seem justified. This argument assumes, however, that these were the only two choices: invade or drop the bomb. On the contrary, there is persuasive evidence that there were other alternatives. Before turning to an analysis of these alternatives, two points should be noted.

First, despite Maddox’s claim (p. 1) that the “official justification for using the bombs was that they saved enormous losses on both sides by avoiding an invasion of Japan,” he gives no citation. In fact there is no “official justification.” There are various statements by various U.S. officials at different times, most of which refer only to American casualties. No one has found any evidence from the internal record showing any policy maker worried about Japanese civilian casualties in an invasion. And it is hard to believe that the same policy makers who so blithely burned up hundreds of thousands of Japanese civilians would be concerned about Japanese invasion costs.15

Second, high Japanese civilian casualties are often blamed on the fanaticism of Japanese resistance. Some of this fanaticism was a myth propelled by racist U.S. stereotypes and carefully constructed Japanese government propaganda.16 To the extent that a fight-to-the death sentiment did exist among Japanese, however, it was a phenomenon with social causes, and one of the key causes was U.S. racism. Much of the discussion about racism and the bomb deals only with the question of whether racism played a role in the decision to use the weapon. Just as anti-Japanese racism documented by Takaki and others helps explain the far greater hatred by the American public and GIs for Japanese than Germans, the relocation into concentration camps of people of Japanese, but not German or Italian, descent, and the lesser degree of hesitation and caution shown in launching conventional attacks on civilians in Japan than in Germany,17 so too racism made Japan an easier atomic target than Germany would have been.

But racism was crucial in another respect as well: it encouraged precisely the kind of last-ditch resistance that U.S. policy makers said the bomb was needed to overcome. Postwar public opinion surveys in Japan found that more than two-thirds of the population expected that defeat would bring “brutalities, starvation, enslavement, annihilation” (Sherry, p. 314). Obviously this belief was encouraged by Japanese leaders, but their propaganda was significantly aided by pre-war anti-Japanese racism in the United States, by the relocations, by the reluctance of U.S. troops to take prisoners, by exterminationist statements made by prominent Americans, and by such well-publicized occurrences as the gift to President Roosevelt of a letter-opener made from the bone of a Japanese soldier or the Life magazine picture of a woman whose boyfriend sent home a skull from the Pacific.18 When the U.S. broadcast to Japan that it would not be destroyed if it surrendered, Japanese broadcasters quoted Admiral Halsey’s recommendation that Shinto shrines be bombed.19 Don’t judge the Americans by what they said, Prime Minister Suzuki told the Japanese people, but by their deeds. And fire-raids that wiped out hundreds of thousands of civilians were awfully dramatic deeds.20 In these circumstances, that many Japanese were willing to support their leaders’ calls for fanatical or suicidal resistance should not be very surprising.

Warnings and Demonstrations

Bernstein (DH, p. 235) comments that in examining alternatives to the bomb, it is important to keep in mind that policy makers at the time were not seeking alternatives to the bomb; the bomb didn’t pose sharp moral dilemmas for them, and they gave little consideration to any alternatives. Bernstein’s point is well taken, but it should not stop us from rendering a moral judgment regarding the dropping of the bomb. (The cops who beat Rodney King may not have been looking for alternative methods of subduing him, but that doesn’t prevent us from condemning their behavior.) If there were alternatives to dropping the bomb, then the moral argument that the bomb had to be used to forestall a horrific invasion fails. Of course, if the alternatives were unknown to the policy makers, or if they had good reason to believe that the alternatives wouldn’t work, then there is no moral onus. In fact, however, the possibility of each alternative was made known to top officials and there is persuasive evidence that they did not have good reasons for rejecting them.

The first alternative was to modify the way in which the bomb was used, either by (1) providing a warning first, (2) conducting a demonstration of the bomb’s power, either on some uninhabited area of Japan, a Pacific island, or even at Alamogordo, New Mexico, (3) dropping the bomb on a genuine military target, and (4) some combination of the above. These options were proposed at one time or another not just by dissenting scientists (who it might be argued were unaware of the realities outside their labs), but by such people as the Army Chief of Staff, the Navy and War under secretaries, and the later head of the Atomic Energy Commission (Bernstein, DH, p. 261; Alperovitz, pp. 225, 332-33; Lifton & Mitchell, pp. 141-42, 135). All of these options were rejected with the most cursory of consideration. The counter-arguments are worth examining.

One objection to both a demonstration drop in Japan and any warning that a specific target was to be hit was said to be that the wily Japanese might move Allied prisoners of war into the drop site (Byrnes, p. 261). Let us leave aside the fact that when Air Force officials in Guam received unconfirmed information that there might be an Allied POW camp one mile north of the center of the Nagasaki and asked the War Department whether this influenced the choice of target, they were told “Targets previously assigned … remain unchanged.”21 More significant is the fact that the Japanese hadn’t used POWs to deter incendiary attacks, when they might well have done so. And if U.S. policy makers worried about prisoners being moved to a demonstration site, why did they drop leaflets on Tokyo on August 13 warning the city to be evacuated?22 Since we know that Tokyo was still considered a possible atomic target (Craven & Cate, pp. 732-3; Lifton & Mitchell, p. 29), the leaflets could have led Japanese authorities to shift large numbers of POWs to the city.

A second argument against a demonstration or warning is that the bomb might turn out to be a dud, and thereby give aid and comfort to the Japanese militarists (Byrnes, p. 261). This too is not very compelling. First, after the test at Alamogordo fears of the bomb not working were very small. The test showed that the plutonium device worked, and the uranium device was considered so much a sure thing that it didn’t even have to be tested. Byrnes says in his memoirs that a static test was not a guarantee that a bomb would detonate when dropped from a plane. But then why when he learned of the successful test did he actively try to discourage Soviet participation in the war (Alperovitz, pp. 267-75)? And if Truman feared a dud, then how do we explain his telling junior officers on board the Augusta about the bomb before it was dropped? If it were a dud, word would have gotten out when the ship docked, giving the same comfort to Japanese militarists as a failed demonstration (Lifton & Mitchell, p. 157).

Moreover, the aid and comfort argument contains a logical flaw. Either Japanese leaders intended to fight to the bloody end or they did not. If they did, then there was no risk of emboldening them. If they did not, then the invasion would not have been necessary, and the moral argument for the bomb collapses.

Some have argued that a demonstration was impractical because the United States only had two bombs on hand and therefore couldn’t afford to waste one. The bombs, however, were in production and the next one would have been available later in August, with three more ready in September, and possibly seven or more in December.23 There is thus no reason why one bomb couldn’t have been spared for a demonstration.

Maddox offers another argument against a demonstration (p. 148): U.S. officials “assumed Japanese hardliners would try to minimize the first explosion or to explain it away as some sort of natural event such as an earthquake or a huge meteor.’That was one of the reasons for rejecting a demonstration.” He provides no citation, but in any event if U.S. officials worried about this, the problem could be easily remedied. They could have flooded Japan with leaflets beforehand warning that an atomic bomb was coming. If hardliners then tried to claim that the explosion was an earthquake or meteor, U.S. power would appear even more awesome, able to call down natural catastrophes on Japan at will. Allen and Polmar (p. 209) argue that a demonstration would have been hard to arrange, and anyway the Japanese might try to shoot down the U.S. plane carrying the bomb. U.S. control of the air, however, was near total over Japan, and absolutely total over many Pacific islands. And, again, U.S. officials didn’t worry that the warning leaflets they dropped on Tokyo on August 13 would endanger the plane with the third bomb. Allen and Polmar (p. 209) also claim that after witnessing a demonstration Japanese leaders could have spent weeks or months debating what they had seen. But nothing would have prevented U.S. officials from declaring that after such and such a time they would move on to bomb a military target.

In fact, none of the arguments considered thus far addresses the option of hitting a military target. And since Japanese leaders — even the emperor and other members of the “peace faction,” as Herbert Bix has shown (DH, 210-14; 1992) — were deeply callous to civilian casualties, there is no reason to think that wiping out an air base, for example, would have had much less of an impact on Japanese decision-making than did destroying Hiroshima.

Would They Work?

Would a non-combat demonstration or a warning have worked, that is, have induced a Japanese surrender? The best answer to this was provided by Under Secretary of the Navy Bard, who said no one really had any sure knowledge of the thinking among Japanese leaders, and therefore the moral thing to do was try (Alperovitz, p. 225). Even if later evidence were to show that Japanese leaders would not have surrendered, the moral argument is unaffected.

Bernstein argues that since we now know that the Japanese military opposed capitulation even after two bombs and the entry of the Soviet Union into the war, it is unlikely — perhaps a 5-10% chance — that a non-combat demonstration would have produced a surrender before November 1 (DH, pp. 237-38). The new documentation from the Japanese side, however, suggests the opposite. Bix has shown that within the “peace faction” a major concern was whether a surrender would be seen by an increasingly restive population as confirmation that the country’s leaders had irresponsibly led them into a hopeless war. To some of these officials, the bomb was a convenient, face-saving excuse for getting them out of the war without having to admit their domestic weakness. Bix (DH, pp. 217-18) quotes one member of the Supreme War Council, Yonai Mitsumasa, as saying on August 12 that the atomic bombs were “gifts from the gods.”

This way we don’t have to say that we have quit the war because of domestic circumstances. Why I have long been advocating control of the crisis of the country is neither for fear of an enemy attack nor because of the atomic bombs and the Soviet entry into the war. The main reason is my anxiety over the domestic situation. So, it is rather fortunate that now we can control matters without revealing the domestic situation.24

But if the bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki were a convenient excuse, then so would a bomb detonated over an uninhabited island.

Now, of course, there is no evidence that U.S. policy makers at the time knew that Japanese leaders were concerned about domestic pressures. (A few individuals in the Foreign Morale Analysis Branch of the U.S. Office of War Information were aware of weakening Japanese morale, but their reports were apparently never read by any policy-maker, at least in part because of the prevailing racist anti-Japanese stereotypes [Dower, 1986, p. 138; Dower, 1993, p. 103].) But without knowing the precise source of Japanese leaders’ concern, U.S. officials (who were reading Japanese cable traffic) could see that Japanese leaders were looking for a way out of the war. One well-informed journalist later wrote that Secretary of the Navy James Forrestal believed “that the Japanese were anxiously looking for a face-saving way to surrender” and that to drop “the bomb on a solely military target, or, at least, on a sparsely populated area and then issue a warning” might “be all the face-saving excuse a desperate Japanese Government would need to surrender” (Alperovitz, pp. 369-70).25

The Soviet Entry

In August 1945 Japan was faced with another powerful shock that might also have provided an excuse for Japanese surrender: the declaration of war by the Soviet Union. Here then was another alternative to using the bomb without the need for the invasion: waiting for Soviet entry into the war.

The military significance of Soviet entry has been much debated, often with an eye to Cold War positions. Thus, the Daily Worker, while endorsing the use of the atomic bomb on Japan, considered the Red Army the key to Japanese defeat.26 Truman, on the other hand, insisted that Soviet participation was wholly irrelevant (Craven & Cate, pp. 712-13).

There are four reasons why the Soviet attack might have induced Japanese surrender. The first, and most straight-forward, reason was that Soviet forces rapidly defeated Japan’s once-mighty Kwangtung army. Second, the defeat of Japanese troops on the mainland may have caused Japanese leaders to reassess the prospects for homeland defense against the even more formidable American military. Third, the Soviet Union might soon land on the Japanese home islands, unleashing pent-up radical sentiments among the population, endangering the Imperial institution and the ruling elite. And even if Soviet troops didn’t actually invade the home islands, the longer they participated in the war, the greater a role they would be able to demand in a post-war occupation. And fourth, it was through the Soviet Union that Japanese leaders hoped to arrange a negotiated peace with the Allies. Some Japanese officials hoped to get Moscow on their side, an admitted long-shot, but many Japanese leaders believed that as long as the Soviet Union even remained neutral it would be possible to hold out for better terms. Once the Soviet Union entered the war, however, all these prospects would have disappeared.

Examinations of the Japanese evidence, including post-war interrogations of Japanese officials, have yielded conflicting claims as to the relative importance of the atomic bombs and the Soviet declaration of war as causes of the surrender. Given that the two bombs were dropped three days apart, with the Soviet war declaration in between, it is not surprising that the evidence is murky.27 That the Soviet declaration of war had a profound effect on Japanese leaders, however, seems indisputable. After the Hiroshima bomb, Prime Minister Suzuki was still waffling. When he heard the news of the Soviet entry, he asked the chief of the cabinet planning board whether Japanese forces could repulse the attack. Told no, Suzuki responded “Then the game is up.”28 On August 13, one of Suzuki’s naval aides asked him if he couldn’t delay the peace effort as the army suggested. “Impossible,” he replied. “If we don’t act now, the Russians will penetrate not only Manchuria and Korea but northern Japan as well. If that happens, our country is finished. We must act now, while our chief adversary is still the United States.”29

Bernstein estimates the chances of the Soviet declaration of war inducing surrender as between 20-30% (DH, p. 247). The question, however, as he correctly notes, is not what the actual chances were but what U.S. officials thought they were. One piece of evidence is a statement General Marshall made to Truman on June 18, 1945: Russian entry “may well be the decisive action levering them into capitulation at that time or shortly thereafter if we land in Japan” (Potsdam, I:905). Bernstein argues (DH, p. 244) that this quote has been misinterpreted, that in fact the quote stresses the importance of Soviet entry “if the invasion occurs, not without the invasion. A Soviet attack alone was not seen as likely to be decisive.” In other words, Bernstein interprets the statement as if the phrase “if we land in Japan” were at the beginning of the sentence, applying to both the “at that time” and the “shortly thereafter” phrases. But this seems to me wrong: the invasion was scheduled for November and Soviet entry was expected before this date (at Yalta Stalin had promised to come in about three months after Germany’s defeat). Therefore, the statement seems to be saying that Soviet entry alone might precipitate an immediate Japanese surrender or if not, shortly thereafter when the Kyushu invasion takes place. This doesn’t mean that Marshall saw the Soviet declaration of war alone as necessarily leading to surrender, but that it well might. (And even if it didn’t, Marshall seemed to be saying that there was then a good chance that surrender would follow the Kyushu landing, without the need for the second invasion of the Tokyo plain.)

In his new book, Alperovitz (p. 124) has cited another piece of evidence bearing on this question: Truman wrote in his memoirs, in a little noticed comment, that he was going to Potsdam to get the Russians in the war as soon as possible because “If the test [of the atomic bomb] should fail, then it would be even more important to us to bring about a surrender before we had to make a physical conquest of Japan.” This seems to be a fairly compelling indication that Truman believed that there was an alternative to using the bomb that had some chance of success. Yet he chose to use the bomb.

Of course, many U.S. policy makers were eager to minimize Soviet influence in post-war Asia. If the Japanese surrender could be obtained before Soviet entry, then the United States might even be able to renege on its territorial promises made at Yalta. This perceived need to check the Soviet Union in Asia has become another argument in favor of dropping the bomb: by hastening the end of the war, by compelling surrender before the Red Army got very far, millions in Asia and Japan were spared the prospect of Soviet rule. In Buruma’s words (p. 33),

As subsequent events in China and the Korean peninsula have shown, Truman was right to worry about Soviet power in northeast Asia. It certainly would not have suited US interests, or those of Japan for that matter, if the Japanese archipelago had been divided into different occupation zones, with Stalin’s troops ensconced in Hokkaido.

Some of the territories promised Stalin at Yalta had been seized from Russia by Japan, and some were places where the population might have welcomed Soviet rule, but clearly some represented nothing more than a Soviet land grab. Any U.S. objection to this sort of territorial aggrandizement, however, was hardly very principled, given Washington’s plans for occupying dozens of Pacific islands and supporting the return of Asian colonies to their European masters.30 It is not clear what Buruma thinks “Soviet power” did in China that made Truman right to be worried; certainly Soviet neutrality in the Chinese civil war was exemplary compared to the intervention of Washington. And in Korea, U.S. interference with local self-determination was at least as serious as that by Moscow.

As for Japan itself, had it undergone the fate of Germany, that would have been pretty grim. However, it could also have been treated like Austria, from which all occupation troops were withdrawn on condition that the country remain neutral. (Stalin offered the same arrangement on Germany, but Washington, determined to add to NATO strength, refused.) A neutral Japan might have suited the interests of the Japanese people quite well. And if the choice were between a neutral Japan with Hiroshima and Nagasaki intact, or a Japan as a U.S. Cold War ally, with 200,000 fewer people, the choice wouldn’t even be close.

U.S. General Douglas MacArthur noted that “Every Russian killed was one less American who had to be” (Sherry, p. 340), which would have been a dubious moral improvement. But by overwhelming the Japanese forces, Soviet entry into the war would have led to lower casualties over-all compared to a solo U.S. invasion of the Japanese home islands. However, although the number of Soviet and Japanese troops killed in combat was small (at least by the Japanese count), there were still many Japanese civilians on the Asian mainland who died in the Soviet attack and its aftermath, and as many as 300,000 Japanese prisoners of war who were never repatriated from the USSR, presumably dying at forced labor.31

Actually, if the Potsdam Declaration had included a warning about the coming Soviet entry into the war, Japan finding its hopes for a negotiated settlement dashed might have folded on the spot, obviating the need for military action at all. (This had been Churchill’s view: that simply announcing Soviet adherence to the Allies in the Pacific “might be decisive” [Alperovitz, p. 371].) Nevertheless, Truman decided without consulting Stalin not to have the Soviet Union sign the Potsdam Declaration, thus not warning Japan of Moscow’s impending entry into the war (Alperovitz, pp. 377-81).32

Continuing the Conventional War

The U.S. Strategic Bombing Survey issued a report in 1946 stating that “in all probability” Japan would have surrendered before November 1, 1945, even if there were no atomic bomb, no declaration of war by the Soviet Union, and no planned invasion. Bernstein (DH, pp. 251-52) and others have argued that the report ignored crucial counter-evidence and depended too heavily on interviews with Japanese officials who wanted to affirm their eagerness to surrender. Some of the evidence consisted of economic data showing the abysmal state of Japan’s war industries, the exhaustion of its oil reserves, and the destruction of its merchant shipping. Newly mobilized troops were being deployed virtually unarmed. Would these conditions have led to Japanese surrender? The answer isn’t clear, and it probably would have depended at least in part on how Japanese leaders viewed the domestic reaction to continuing war-weariness and deprivation. Bix (DH, p. 218n63) guesses that continued heavy conventional bombing would have led to surrender. If conventional bombing continued as before, however, there still would have been massive civilian casualties. If the bombing were redirected to support the extremely effective naval blockade in order to induce starvation (perhaps with attacks on rice crops, as the Strategic Bombing Survey recommended) the civilian suffering might have been less since starvation is gradual, affording the opportunity to surrender but might well have taken a devastating toll on children and the elderly.

There was a humane alternative: the Navy could have continued its blockade, with its crippling effect on Japan’s war industries, while allowing food through. Better yet, the U.S. air force could have confined its bombs to military targets and dropped food on Japanese cities, along with messages saying “You are not our enemies; our enemies are the warlords.” This, of course, is not the way World War II had been waged since its inception, but it is the only way consistent with democratic and just war aims. Would it have been right to ask a U.S. pilot to risk his life to feed Japanese civilians? By this time U.S. raids over Japan ran fewer casualties than training missions in the United States, but in any event many pilots were asked to risk their lives dropping propaganda leaflets over Japan (with probably more contribution to the defeat of Japan than the incendiary raids); food drops would have been the most effective of propaganda missions.

Unconditional Surrender

Alperovitz argues that the fundamental reason why the bomb was never the only alternative to invasion was that Washington could as many policy makers urged have clarified its surrender terms, particularly to guarantee the retention of the Japanese throne, and that such clarification, in conjunction with the shock of Soviet entry into the war or maybe even on its own, would have prompted a Japanese surrender. According to Alperovitz, this was the recommendation of every single high-level adviser except Byrnes. That Truman rejected the advice, Alperovitz argues, suggests that he was not looking for a way to end the war before using the bomb.

*

Why did the United States demand that Japan surrender unconditionally? This policy had a number of sources. One was simple fanaticism, as illustrated by the telegram Senator Richard B. Russell sent to Truman after Hiroshima opposing the acceptance of any conditions on Japanese surrender:

If we do not have available a sufficient number of atomic bombs with which to finish the job immediately, let us carry on with TNT and fire bombs until we can produce them….Our people have not forgotten that the Japanese struck us the first blow in this war without the slightest warning. They believe that we should continue to strike the Japanese until they are brought groveling to their knees. We should cease our appeals to Japan to sue for peace. The next plea for peace should come from an utterly destroyed Tokyo (quoted in Kecskemeti, p. 165).

Many other arguments for unconditional surrender, however, came not just from the right end of the political spectrum, but also and even predominantly from the left. It was argued that (1) a Japan that was not thoroughly defeated would later emerge to start another war, just as Germany had risen from its World War I defeat, (2) thorough-going democratization of Japan could only take place if there were unconditional surrender, (3) announcing the retention of the emperor would violate the principle of the Atlantic Charter that declared post-war governments must reflect the will of their populations, (4) unconditional surrender was necessary for war crimes trials which were needed for reasons of justice and to allow people in Japan and elsewhere to know the truth, and (5) conditional surrender would promote distrust between the United States and the Soviet Union, as the conditional surrender of Italy had done. Each one of these arguments had some validity, but was ultimately based on flawed political reasoning.33

A conditional surrender could have guaranteed that Japan would not later become a military threat. It is true that the new Japanese constitution promulgated during the U.S. occupation outlawed war, but this is not what has kept Japan from being a significant threat to the peace since 1945. Rather, Japanese militarism has been limited by the sentiment of the Japanese people, despite efforts by Washington to get Japan to repeal the no-war clause from its constitution (see Dower, 1993, pp. 27, 161, 230-31). The United States is not and has not been a pacifist power, and to have expected it to promote pacifism in Japan on any long term basis was naive.

Some important democratic reforms were introduced into Japan during the early years of the U.S. occupation. But as should have been predictable by those who knew that the U.S. record of concern for democracy was always subordinate to its concern for its imperial interests as soon as U.S. interests were better served by restoring the old elite and the monopolistic firms, by purging the left and restraining unions, U.S. policy shifted. And whatever the soundness of the arguments for getting rid of the emperor, they can hardly be a compelling reason for Washington’s keeping the war going given that the United States ultimately allowed Japan to retain the emperor.

Truth-telling is important. The war-crimes trials following the Pacific War, however, departed from the truth in significant respects: U.S. officials suppressed evidence relating to the emperor’s war guilt, to Japanese biological warfare (so that the U.S. military could gain access to Japanese experimental data), and to the war crimes of the Allies. Much data on Japanese atrocities was produced, but its impact on the Japanese public was surely lessened by the fact that the trials represented victors’ justice. A few major Japanese war criminals were executed, but many of the guilty were soon back in control.

U.S. exclusion of the Soviet Union from a role in the occupation of Japan (as heavy-handed as Stalin’s actions in Romania and Bulgaria) did contribute to worsening relations between Washington and Moscow, and an early peace with Japan might well have made Stalin suspicious that Truman was trying to deny him the territorial concessions promised at Yalta. However, Stalin had not been adamant about unconditional Japanese surrender in earlier discussions with Hopkins (he personally favored it, but understood the short-term benefits of accepting conditional surrender; he proposed telling Japan that its surrender would be conditional and then imposing harsher terms which would eliminate Japan’s military potential). In any event, Stalin’s real interest was keeping Japan out of a U.S. military alliance; if avoiding tensions with Moscow had been Washington’s aim here, U.S. officials could have declared their intention to neutralize Japan.

Could an early surrender have been obtained by offering to retain the emperor? Bix (DH, pp. 222-23) argues that Japanese leaders who are often characterized as wanting only to retain the emperor actually wanted to maintain the national polity, by which they meant the emperor’s theocratic rule, the ruling elite, and the existing undemocratic political system. Thus, in Bix’s view, an early surrender could have been obtained, but at the cost of leaving authoritarian structures in place, rather more authoritarian than ultimately emerged out of the U.S. occupation.

Democracy is an important value, and worth fighting for. But Japan would hardly have been the only place left in the world where dictatorship prevailed. Should the United States also then have gone to war to bring democracy to the Soviet Union, or to colonial Asia, or to the Jim Crow South? It might make sense to fight unconditionally for worldwide democracy, but this was not what the Pacific War nor U.S. foreign policy was about. So while it would be depressing to see war criminals and dictators still in power in Japan, it would have been no more unsettling than seeing them in power in many other countries, often with U.S. complicity.

The main beneficiaries of Japanese democracy would presumably be the Japanese people. It is bizarre then to obliterate two hundred thousand of them, and threaten to obliterate millions more, unless their leaders agreed to surrender so that their subjects could have democracy. As Walzer has argued (pp. 267-68), there may be times when it is right to demand unconditional surrender, but Japan was not so uniquely evil that this was one of those times; if the choice came down to massacring Japanese civilians or accepting a less than unconditional surrender, the United States was morally obliged to accept the latter. The moral logic is the same here as in the case of a criminal who is holding hostages: we might look for some alternative to either letting the hostages die or letting the criminal get away, but if our options narrowed to these two, we must accept the latter.

The argument for accepting a conditional surrender is political as well as moral. It is one of the central insights of democratic thought that democracy cannot be imposed from the outside. U.S. State Department officials acknowledged in internal documents (Potsdam, I:886) that an attempt from the outside to abolish the institution of the emperor would probably be ineffective unless the Japanese people changed their attitude.

The attitude of the Japanese population was changing. The experience of war and the elite’s indifference to any except its own interests engendered much popular unrest. Japanese leaders may have over-estimated the degree of popular discontent — I suspect internal upheaval was not imminent34 — but had the war ended with a conditional surrender, allowing the national polity to remain intact, there is no reason to think that democracy would not have burst forth later, particularly once the artificial unity of wartime was over.

Bix’s evidence that Japanese leaders wanted more than just the retention of the emperor doesn’t tell us whether they would have accepted this more limited condition had it been offered. The U.S. unconditional surrender demand did not inspire Japanese officials to clarify their thinking regarding conditions. Again, though, the real question is not whether the Japanese would have accepted particular terms but whether U.S. officials thought they would. And many seemed to share the State Department analysis that considered Japanese concern over the fate of the throne “the most serious single obstacle to Japanese unconditional surrender” (Potsdam, I:884).35

Some U.S. policy makers worried that offering terms for surrender would be seen by the Japanese military as confirming their view that the longer they held out, the better terms they would get. But Washington did not have to announce that it was offering a first, tentative peace proposal, to be haggled over. If, for example, the United States had included in the Potsdam Declaration conditions for an immediate surrender coupled with a warning that by such and such a date the Soviet Union would enter the war, Japanese leaders might well have concluded that it would be wise to surrender without delay on the proffered terms.36 And it was this sort of “two-step” process modified terms plus the threat of Soviet entry that many U.S. officials urged, as Alperovitz documents. Bernstein (DH, pp. 240-41) thinks a guarantee of the throne on its own (without other substantial concessions as well) would have been “quite unlikely” to have produced a surrender before November 1; Bix (DH, p. 224) concludes that the guarantee alone would “probably not” have led to prompt surrender. However, Bernstein (DH, p. 254) considers it “very likely” that the guarantee of the emperor, plus Soviet entry and the continuing siege would have ended the war.37

Atomic Diplomacy

Why did Washington reject all the potential alternatives to the bomb? Maddox argues that considerations relating to the war with Japan were the only relevant factors, but this is not credible. The war with Japan cannot explain why Truman did not have the Soviet Union sign on to the Potsdam Declaration, nor why he couldn’t postpone the first bomb until after the Soviet declaration of war, nor why he dropped the second bomb before assessing the impact of Soviet entry. It is well known that Truman delayed the opening of the Potsdam conference to coincide with the test of the bomb at Alamogordo. But this, says Maddox, was “not in order to intimidate the Russians.” Rather, Truman wanted an ultimatum to come out of the conference, and “Knowledge of a successful test at the outset of the conference would influence the ultimatum’s content and permit its issuance in time for the Japanese to reply before the first bomb was ready for use” (p. 52). This would be a persuasive argument if the Potsdam Declaration had in fact made some reference to the bomb; but it did not, so Maddox’s argument makes no sense. And, of course, by delaying the conference, Truman was also shortening the amount of time the Japanese would have to contemplate compliance before the bomb was dropped: again, not something that would be done if the goal were only to maximize the chances of Japanese surrender.

Truman was reported to be extremely enthusiastic after receiving news at Potsdam of the successful Alamogordo test, and Maddox says (p. 100) this enthusiasm was simply because he believed the war with Japan would end sooner. This interpretation, however, ignores the contemporaneous accounts of the conference that document the fact that U.S. officials saw the bomb as strengthening their hand vis-a-vis the Soviet Union (Alperovitz, pp. 259-61). And even Maddox acknowledges (p. 117) that Byrnes attributed Soviet acceptance of the U.S. position on reparations to the bomb.38

Alperovitz argues that considerations relating to the Soviet Union, and only these considerations, explain the dropping of the bomb. He rejects reasons relating to the war with Japan (which, he says, did not require the use of the bomb, given the consensus of all Truman’s top advisers other than Byrnes that a clarification of the surrender terms could end the war); he rejects as well explanations based on momentum, bureaucratic politics, racism, and the like. Moscow could have figured in the decision of U.S. policy makers to use the bomb in two ways: the bomb could have been dropped (1) to hasten the Japanese surrender before the Soviet Union made too many gains in Asia, or (2) to intimidate the Soviet Union. Or both. There are reasons, however, why these calculations are not likely to have been decisive.

If motive (1) were the only reason for dropping the bomb, then we would have expected U.S. officials to have sought an earlier Japanese surrender by modifying unconditional surrender, and to have responded more quickly and less ambiguously to the Japanese surrender offer of August 10. Alperovitz’s effort to explain away these problems is unconvincing.

On June 18, 1945, responding to a suggestion that unconditional surrender be clarified, Truman told aides that he had left the door open to Congress to take action in this regard but that he did not feel that he could do anything to change public opinion on the matter at that time. Alperovitz (pp. 65-66) comments that “something strange” seems to be going on, since Truman’s previous public statements reveal no indication that he ever expected Congress to take the lead on this issue, and then Alperovitz suggests that “Possibly, the recording secretary misheard the president.” There is no reason, however, to have to wish away evidence. Public opinion was strongly in favor of unconditional surrender. Alperovitz makes much of the fact that various Republican leaders were calling for modified terms, but surely Truman, who had recently taken over Roosevelt’s oversized mantle, would not have been oblivious to the strong sentiment among liberals, Democrats, and the public at large. (Indeed, FDR had earlier rejected the urgings of his advisers to modify unconditional surrender before the bomb was a factor.) That Truman might have been open to Congress taking action, while being reluctant to try to change public opinion on his own, seems perfectly understandable. I have argued that to kill large numbers of civilians in an effort to obtain unconditional surrender was immoral, and Alperovitz is surely right that there was enough softness in public opinion for Truman to have been able to follow another course. This is not the same, however, as saying that public opinion didn’t matter or that there were no costs to Truman of pursuing a different course if he had wanted to do so. Policy makers shared with much of public opinion the view that killing civilians was permissible, that the Japanese were treacherous and inferior, and that the United States had the right to do things that were condemnable in others. Indeed, the lies by U.S. policy makers to disguise many of their actions suggest that in some respects they were more willing than the public at large to engage in such actions.

On August 10, 1945, the Japanese government offered to surrender as long as the prerogatives of the emperor were maintained. U.S. policy makers met to consider a reply and rejected a draft prepared by Leahy, before agreeing on a message that said the emperor would be subordinate to the Allied Commander. This wording implied the retention of the emperor, but did not say so explicitly. The lack of explicitness caused hesitation in Japan. Again, if Washington were concerned only with minimizing Soviet gains in Asia, then the ambiguity of the message is inexplicable, for it delayed the end of the war by four days. It seems clear that policy makers really were concerned about avoiding the political “crucifixion” (to use the word of one diarist) that might result from appearing to backtrack from unconditional surrender. Alperovitz (p. 417 ) simply says that the U.S. reply “allowed for the Emperor’s continued presence” and doesn’t acknowledge the ambiguity. Of course, the United States did permit the emperor to remain in fact, but this wasn’t clearly known until later, so the public reaction was muted.

Alperovitz is correct that, despite public opinion, many officials, particularly in the military, wanted to clarify the surrender terms. As the State Department argued, however, surrender was a political objective of the war and the military’s job was to fight until that objective was reached.39 Alperovitz says (p. 308) that two vocal State Department opponents of modifying the surrender terms were not very influential. Theirs, however, was the Department’s majority view and reflected in policy forums (Villa, p. 77).

If the key goal of U.S. officials was motive (2), to intimidate the Soviet Union in Europe, then another question arises. Why wouldn’t a demonstration of the bomb have sufficed to let Moscow know of Washington’s newly-acquired power? To be sure, wiping out civilians showed Moscow that the United States not only had the weapon, but was morally capable of using it. (Lifton and Mitchell [p. 220] remind us that during the Carter administration a State Department official declared that “the Soviets know that this terrible weapon has been dropped on human beings twice in history and it was an American president who dropped it both times. Therefore, they have to take this into consideration in their calculus.”) On the other hand, when Stimson recommended eliminating Kyoto, a cultural and religious center, from the atomic bomb target list, he noted that “such a wanton act” might make it impossible to reconcile Japan to “us … rather than to the Russians” (Alperovitz, p. 532). But the same logic applied to other cities as well, so if only considerations related to the Soviet Union were at stake, there was as good an argument for a demonstration as for actual combat use. Likewise, there was no need to drop a second bomb in order to impress Moscow: one would have been sufficiently intimidating. The destruction of Nagasaki, however, was useful for limiting Soviet gains in Asia and for justifying exclusive U.S. occupation of Japan.

It seems clear that the desire to gain advantages vis-a-vis the Soviet Union alone cannot explain the dropping of the bomb. If U.S. officials had no war-related motives for sticking with unconditional surrender, then why did they approve the Kyushu landing, since an invasion would never have been necessary? On the other hand, Bernstein’s claim that without anti-Soviet calculations the bomb would have been used just the same also has problems. Without the desire to block Soviet gains in Asia, there would not have been the same need to keep Moscow from signing the Potsdam Declaration, nor to rush the attack on Hiroshima before seeing the impact of the Soviet declaration of war.

However, Bernstein is right, I think, when he says that U.S. policy makers, who had been incinerating Japanese civilians without the slightest qualms, didn’t agonize over the atomic bomb decision. Nor, it might be added, did they give much thought to how nuclear weapons would transform all subsequent history. For them, it was just more of the same, with added diplomatic benefits vis-a-vis the Soviet Union. The atomic bomb, however, was not just more of the same. It may have killed as many civilians as conventional weapons, but for the first time it created the possibility of destroying the human race.

Notes

1. Christopher Thorne, The Issue of War, New York: Oxford UP, 1985, p. 33.

2. Herbert Feis, The Road to Pearl Harbor, Princeton: Princeton UP, 1950, p. 272n5. On troop numbers, see U.S. Dept. of State, Foreign Relations of the United States, Japan: 1931-1941, Washington, U.S. Government Printing Office, 1943, vol. 1, p. 430.

3. U.S. Dept. of State, Foreign Relations of the United States, 1936, Washington: U.S. Government Printing Office, vol. IV, p. 265. See generally, see Noam Chomsky, “The Revolutionary Pacifism of A. J. Muste: On the Backgrounds of the Pacific War,” in American Power and the New Mandarins, New York: Pantheon, 1969.

4. For details, see Stephen R. Shalom, “VJ-Day: Remembering the Pacific War,” Z Magazine, July-Aug. 1995.

5. “The War Over the Bomb,” New York Review of Books, Sept. 21, 1995, p. 32.

6. A similar logical confusion is evident in the argument that the atomic bombing was justified because the Japanese were also working on the bomb and would have used it if they had gotten it first (see, for example, Lawrence Freedman and Saki Dockrill, “Hiroshima: A Strategy of Shock,” in Saki Dockrill, ed., From Pearl Harbor to Hiroshima: The Second World War in Asia and the Pacific, London: Macmillan, 1994, p. 209). By the same reasoning, a Japanese apologist could argue that Japan’s use of gas warfare in China was justified because post-war research has shown that U.S. policy makers were prepared to use gas in conjunction with the invasion of Japan. Or a police officer could argue that he was justified in shooting a sleeping felon because, had the situation been reversed, the felon would have shot the officer. Incidentally, the Japanese atomic bomb project was far less advanced than some sensationalist claims would suggest. See John Dower, Japan in War and Peace: Selected Essays, New York: New Press, 1993, pp. 55-100.

7. James F. Byrnes, Speaking Frankly, New York: Harper & Bros., 1947, p. 264.

8. Michael Walzer, Just and Unjust Wars, New York: Basic Books, 1977, p. 267.

9. Robert H. Ferrell, ed., Off the Record: The Private Papers of Harry S. Truman, New York: Penguin, 1980, p. 56. The official log says the meeting began at 10:00 AM and ended at 10:35; see U.S. Department of State, Foreign Relations of the United States: Conference of Berlin (The Potsdam Conference), 1945, Washington: USGPO, 1960, 2 vols., p. II:20 (hereafter cited as Potsdam, with volume and page number).

10. Truman to Cate, Jan. 12, 1953, in Wesley Frank Craven and James Lea Cate, eds., The Army Air Forces in World War II, vol. 5, The Pacific: Matterhorn to Nagasaki, June 1944-August 1945, Chicago: Univ. of Chicago Press, 1953, between pp. 712-13.

11. Harry S. Truman, Memoirs, vol. 1, Years of Decision, Garden City, NY: Doubleday, 1955, p. 417. Truman’s exaggeration, though, is less than that of George Bush who claimed the bombs saved “millions of American lives” (quoted in J. Samuel Walker’s article in the DH symposium, p. 320).

12. For example: Maddox (p. 126, 185n57) and Allen and Polmar (pp. 292-93, 331n) cite a memorandum from medical officers in turn cited in an undated study apparently written in the 1960s; but when one calculates combat deaths, they are only 50% higher than the mid-June War Department estimate for the Kyushu invasion (31,000 compared to 20,000), and nowhere near Truman’s half million deaths figure. Allen & Polmar don’t distinguish between combat and non-combat casualties (though the latter figures, according to War Department historian Rudolph Winnacker as quoted by Alperovitz [p. 468*], “are rather deceiving and include anybody admitted to hospitals or quarters even for the treatment of a sore throat”); Allen & Polmar also make a convenient mathematical error. On the date of the study, see Alperovitz, p. 743n44.

Allen and Polmar (pp. 292, 331n) make much of an order mentioned only in a privately published 1980 manuscript by the Philadelphia Quartermaster Depot for more than 370,000 Purple Hearts for those who might become invasion casualties; however, there is no indication when the order was put through nor any reason to believe that the Quartermaster had access to better data than the War Department planners. In any event, there is no evidence that Truman or other top officials saw these figures, so they could hardly have played a role in the decision-making.

Maddox (p. 60) states that the War Department casualty estimates for the invasion of Japan excluded “the unpredictable number of casualties kamikazes would inflict on crowded troop transports.” The nearest source he cites provides no support for his claim, but it would be bizarre if military planners contemplating an amphibious assault had failed to include losses in landing the invasion force.

Allen & Polmar (p. 208) cite a worst case military analysis (if three separate invasions were needed) that would result in 220,000 battle casualties. To this they add non-battle casualties (accidents and disease), which can be calculated using the ratio of battle to non-battle casualties given in the single invasion scenario. But though the sum comes to 249,411, they state that total casualties “would exceed 250,000 and were climbing toward 500,000.”

13. See The Committee for the Compilation of Materials on Damage Caused by the Atomic Bombs in Hiroshima and Nagasaki, Hiroshima and Nagasaki: The Physical, Medical, and Social Effects of the Atomic Bombings, New York: Basic Books, 1981.

14. Murray Sayle (“Did the Bomb End the War?” The New Yorker, July 31, 1995, p. 53) claims “We now know that Truman had been misinformed about what he was agreeing to.” But Sayle, who also believes that Hirohito was a closet pacifist (p. 49; for decisive counter-evidence, see Herbert P. Bix, “The Showa Emperor’s Monologue’ and the Problem of War Responsibility,” Journal of Japanese Studies, vol. 18, no. 2, Summer 1992, esp. p. 302), seems awfully naive here: we know Truman was aware that the bomb was wiping out “all those kids” (Henry Wallace quoting Truman, quoted in Alperovitz, p. 417).

15. Immediately after Hiroshima, Truman announced: “The Japanese began the war from the air at Pearl Harbor. They have been repaid many fold.” And after Nagasaki he declared:

Having found the bomb we have used it. We have used it against those who attacked us without warning at Pearl Harbor, against those who have starved and beaten and executed American prisoners of war, against those who have abandoned all pretense of obeying international laws of warfare. We have used it in order to shorten the agony of war, in order to save the lives of thousands and thousands of young Americans (cited in Herbert Bix’s contribution to the DH symposium, p. 207).

Neither comment is suggestive of excessive concern for Japanese civilians.

16. See John W. Dower, War Without Mercy, New York: Pantheon, 1986; and Haruko Taya Cook, “The Myth of the Saipan Suicides,” MHQ: The Quarterly Journal of Military History, vol. 7, no. 3, spring 1995.

17. The attack on Pearl Harbor obviously added to the U.S. willingness to target Japanese civilians, but that willingness was there before. Three weeks prior to Pearl Harbor, Army Chief of Staff George C. Marshall told reporters in an off-the-record meeting that if war came with Japan “we’ll fight mercilessly. Flying fortresses will be dispatched immediately to set the paper cities of Japan on fire.” And “There won’t be any hesitation about bombing civilians it will be all-out” (Michael S. Sherry, The Rise of American Air Power: The Creation of Armageddon, New Haven: Yale UP, 1987, p. 109). Washington was also far more cavalier about attacks on civilians in occupied Asia (fire-raids in China and Formosa) than in occupied Europe (Sherry, pp. 284-85).

18. James J. Weingartner, “Trophies of War: U.S. Troops and the Mutilation of Japanese War Dead, 1941-1945,” Pacific Historical Review, vol. 61, no. 1, Feb. 1992, pp. 53-67; Dower, 1986, esp. pp. 52-55, 64-71.

19. Robert J. C. Butow, Japan’s Decision to Surrender, Stanford: Stanford UP, 1954, p. 138.

20. Sherry, p. 303. The U.S. Strategic Bombing Survey asked people after the war whether they believed defeat was inevitable and what led them to that view. Note that this measure of morale is separate from the question of whether one intended to fight to the death. Terror bombing probably increased defeatism while at the same time encouraging fanatical resistance. Incidentally, the incendiary raids had very little impact on Japanese war potential: the naval blockade had already cut off Japanese resources, so that even unbombed factories were left idle (Robert A. Pape, “Why Japan Surrendered,” International Security, vol. 18, no. 2, Fall 1993, p. 195).

21. Martin J. Sherwin, A World Destroyed, New York: Vintage, 1975, p. 234. On the evidence regarding U.S. POWs killed at Hiroshima, see Alperovitz, pp. 612-13.

22. Father Flaujac, “The Bombing of Tokyo,” Bethanie Institution Bulletin no. 5, translated by GHQ, Far Eastern Command, Military Intelligence Section, General Staff, Allied Translator and Interpreter Service, Aug. 14, 1948, in War in Asia and the Pacific, 1937-1949, ed. Donald S. Detwiler and Charles B. Burdick, New York: Garland Publishing, Inc., 1980, vol. 12, p. 8. Leafleting of cities targeted for conventional bombing began earlier that summer (Sherry, p. 312).

23. Barton J. Bernstein, “Roosevelt, Truman, and the Atomic Bomb, 1941-1945: A Reinterpretation,” Political Science Quarterly, vol. 90, no. 1, Spring 1975, pp. 52-53n104.

24. In a related comment, cabinet secretary Sakomizu said the bomb was a chance to end the war without having to blame the military or manufacturers (Robert P. Newman, “Ending the War with Japan: Paul Nitze’s Early Surrender’ Counterfactual,” Pacific Historical Review, vol. 64, no. 2, May 1995, pp. 185-86).