Book Review: Hal Draper, Berkeley, The New Student Revolt. Haymarket, 2020.

Thomas Harrison

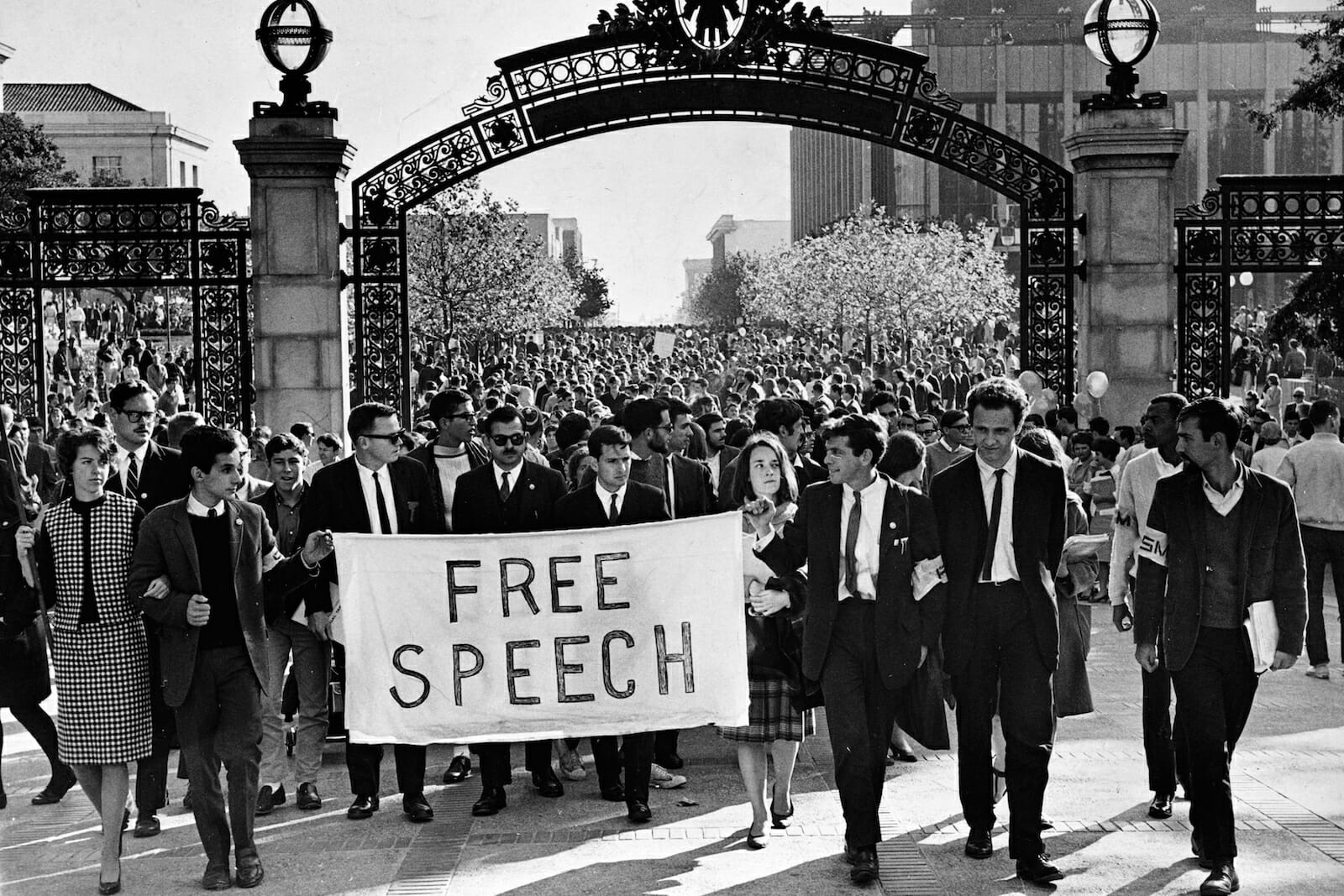

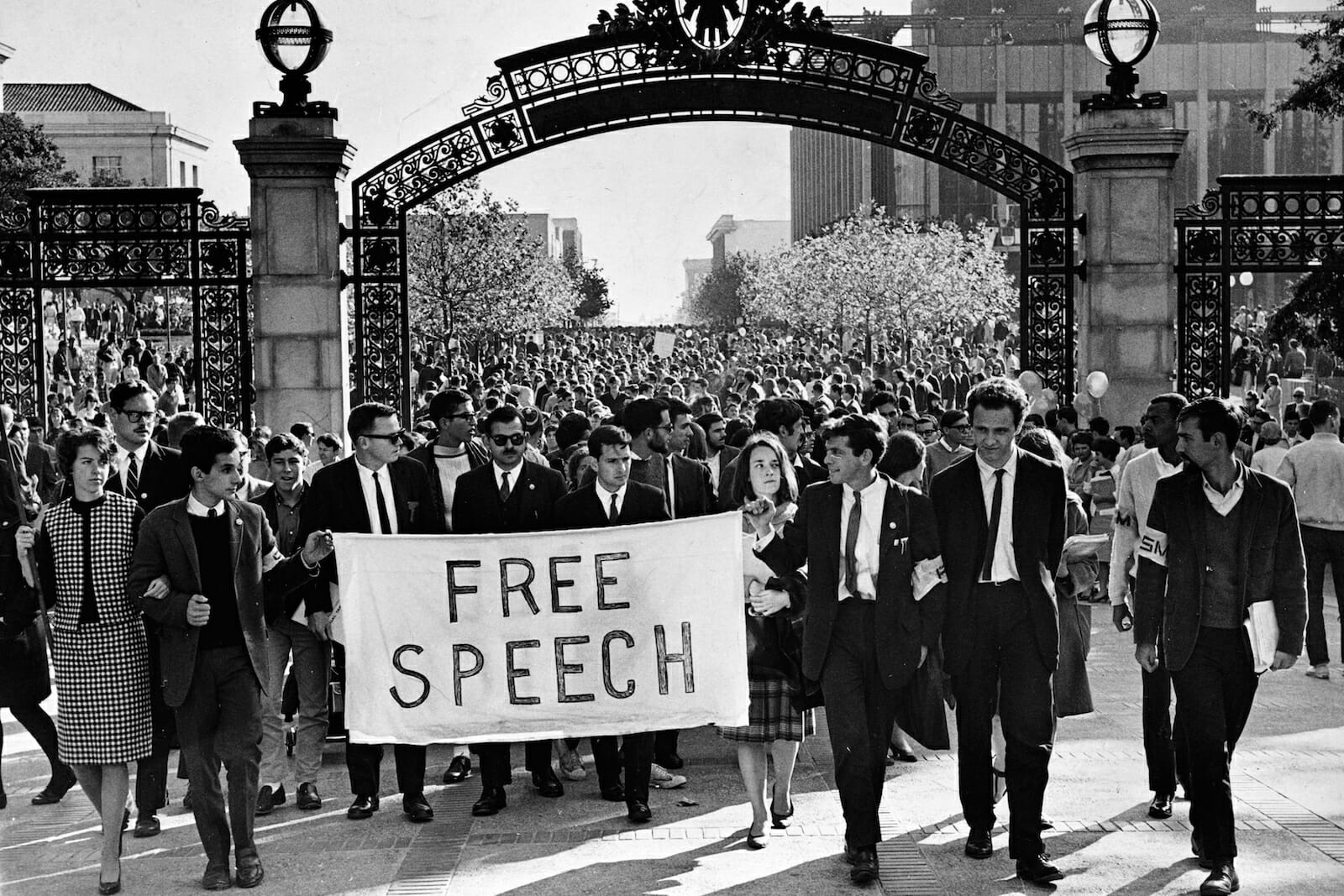

The current mass upheaval has reached a scale not seen in this country since the 1960s. So it is timely that Haymarket Books has republished an account of one of the key revolts in that fabled decade – the 1964 Free Speech Movement (FSM) at the University of California at Berkeley. Originally issued by Grove Press in 1965 and published in a second edition in 2010 by the Center for Socialist History, Hal Draper’s book remains the most vivid narrative and incisive analysis of the FSM that I know. A Marxist scholar of immense learning and a veteran of the revolutionary socialist movement, he was also a deeply involved participant in the FSM itself. Indeed, Draper’s influence led UC President Clark Kerr to call him, hyperbolically, “the chief guru of the FSM.” Berkeley, The New Student Revolt recommends itself to all those interested in the history of protest and the left in this country, but especially, I think, to the young radicals and socialists who are today immersed in the great multiracial movement against racism and police violence and for fundamental social change.

Draper became a Trotskyist in the 30s. He was part of the tendency led by Max Shachtman that split from the Trotskyists in 1940 in a dispute over the nature of the Soviet Union and formed the Workers Party. The group, which changed its name to the Independent Socialist League (ISL) in 1949, stood for what it called the Third Camp, in opposition to both capitalism and the “bureaucratic collectivism” of the Soviet Bloc and Communist China. For most of its history, Hal Draper edited, and contributed frequently to, the group’s weekly newspaper, Labor Action. Shachtman began to move away from revolutionary politics in the 50s, and in 1958 the ISL dissolved, its members entering the Socialist Party. Draper, however, was one of those, like the founding editors of New Politics, Julius and Phyllis Jacobson, who stuck to their principles, and he remained an outspoken revolutionary socialist. By the time the FSM erupted, he had settled in Berkeley and was working in microfilm acquisitions at the UC library.

I entered Berkeley only two years after the FSM, and I knew many of the participants, including Hal. In the 60s, attending UC Berkeley was itself a liberating experience. It was tuition-free to state residents, although there were “incidental fees” of $120 per semester, a bit less than $1,000 in today’s dollars. When I was enrolled in 1966-70, even with no financial assistance from my parents, I could, without too much difficulty, afford fees and living expenses thanks to a small scholarship, federally-subsidized National Defense loans and 15-hours-a-week Work-Study jobs, plus full-time work in the summers. Most students lived in apartments and houses, not dormitories, so they enjoyed a considerable amount of personal freedom.

In Sproul Plaza, a broad square in front of the administration building, Sproul Hall, there were long rows of folding tables at which members of political (mostly leftwing) groups distributed leaflets, sold literature, buttons and bumper stickers and recruited. Every weekday, the tables were there, and people would hang around for hours talking about politics. And after the tables were taken down, they would move to The Terrace, behind Sproul Plaza, and continue discussing things over coffee for hours more. It was like the Agora in ancient Athens.

Berkeley, both the university and the community, had been since the early 60s a magnet for left-leaning, bohemian young people. On Telegraph Avenue, just to the south of the campus, they could be seen patronizing the outstanding bookstores (Moe’s for used books, Cody’s for new) and coffee shops (especially the Mediterraneum—the “Med” – which claimed, dubiously, to have introduced café lattes to these shores). Both campus and community constituted a unique political and cultural world. To attend the three art-house cinemas – for which Pauline Kael wrote the program notes — was to receive a complete education in film history. Everybody, it seemed, listened to KPFA, the local listener-supported radio station founded by pacifists right after World War II, the flagship of the Pacifica network. KPFA featured jazz and classical music, poetry, political commentary (Hal Draper, along with his wife Anne Draper, had a monthly program throughout the 60s), and thorough on-the-ground reporting of protests and demonstrations on and off campus.

The 50s had been, notoriously, a period of repression and conformism, of the “silent generation” of youth. In 1960, the sociologist Daniel Bell proclaimed in The End of Ideology: On the Exhaustion of Political Ideas in the Fifties that radicalism had petered out for good. In the United States, “the fundamental political problems have been solved,” he announced. Along with other theorists of “pluralism” — David Truman, Robert Dahl, William Kornhauser, Edward Shils – Bell redefined democracy as competition among the elite leaders of “groups,” for the passive support of the masses; as long as no one group acquired overweening power, freedom was safe. Freedom for the masses, moreover, was defined mainly in terms of consumer choice and leisure time, rather than political power. The responsibility of managing and maintaining social cohesion was the job of administrators, bureaucrats. As Mario Savio, the FSM’s foremost leader, put it: “The conception that bureaucrats have is that history has in fact come to an end. No events can occur now that the Second World War is over which can change American society substantially. We proceed by standard procedures as we are.”[1]

The experience of Communism and Fascism, and especially McCarthyism – and, in many of their cases, disillusionment with the hopes of their own radical youth – instilled in the pluralists a deep fear of mass movements. They argued that the scale and complexity of “industrial society” made most Americans incapable of using “substantive reason” to grasp large-scale political issues; democracy in the traditional sense – self-government by ordinary informed citizens – was impossible. It was also undesirable. Mass movements were essentially passé, but should they nevertheless arise, they would produce totalitarianism. This was the school of thought that dominated university social science departments.

In the very year in which Bell’s book had come out, however, the tide began to turn. In the late 50s, mass protest had already appeared in the South, most notably with the Montgomery Bus Boycott. Then in 1960 the Civil Rights Movement reached a new stage with the lunch counter sit-in by black students in Greensboro, NC. Following in rapid succession came the Freedom Rides, the Albany Movement, the Birmingham Campaign, and the March on Washington. Protest was becoming the order of the day, and it was spreading north.

Already in those pre-1964 years, UC Berkeley had a small but vibrant culture of leftist politics. Several socialist clubs busily recruited students and played an especially important role in the Civil Rights Movement. A series of off-campus actions initiated by Berkeley-based socialists and other radicals planted the seeds of the FSM. In May 1960, hundreds of students went to San Francisco’s City Hall to protest hearings by the House Committee on Un-American Activities (HUAC). Police blasted the demonstrators with fire hoses and violently dragged them down the marble steps. By 1963, more than a half dozen leftist clubs, plus chapters of the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) and the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), were active at UC. Indeed, it was from the ranks of civil rights activists that most of the FSM’s leading cadre came.

Civil rights actions reached a crescendo in 1963-64. With Berkeley’s Campus CORE taking the lead, the movement focused on employment discrimination. Blacks were mostly barred from jobs in stores, supermarkets, banks, car dealerships – businesses where they would be dealing with white customers. So CORE launched a wave of militant protests: picketing merchants first in Berkeley and then farther afield, culminating in a mass picket in November 1963 of Mel’s Drive-In restaurants in the East Bay and San Francisco. There were sit-ins in the lobby of San Francisco’s Sheraton Palace Hotel and in the showrooms of Auto Row on Van Ness Avenue. Hundreds were arrested, including many Berkeley students. In September 1964 large numbers of Berkeley students went to picket the offices of the Oakland Tribune, a newspaper owned by William Knowland, a power in the California Republican Party and at that moment the state campaign manager for Barry Goldwater.[2]

The president of the seven-campus University of California system was Clark Kerr. Kerr had a reputation as a pro-labor liberal. In his youth he had belonged to the social-democratic Student League for Industrial Democracy, much later the parent organization of Students for a Democratic Society (SDS). Kerr was named Berkeley’s first chancellor when that position was created in 1952. Three years earlier, the Regents had voted to require all UC employees to sign an oath swearing they did not belong to any group advocating violent revolution. Kerr signed the oath himself, but as chancellor he defended professors who refused to sign on principle. Then upon becoming president of the entire university system in 1957, he lifted a ban on Communist speakers. At the same time, though, he replaced the ban with a series of petty, harassing restrictions on outside speakers, including requiring the presence of tenured faculty members and a campus police officer, for which clubs had to pay but were not allowed to collect money for that purpose.

Responding to pressure from Knowland and other members of the Bay Area establishment, the Berkeley administration moved to clamp down on campus organizing and advocacy – including raising money to support civil rights work in the South. In order not to be seen as anti-civil rights, however, Kerr and Berkeley’s chancellor, Edward Strong, imposed a ban on all campus-based political activity; there could be no “mounting of social and political action directed at the surrounding community,” only “informative” activity. (This was later amended to permit advocacy of candidates and propositions on the ballot.) In response, a United Front of 20 student organizations was formed, covering the political spectrum from revolutionary socialists and pro-Moscow Communists (the CP-controlled Du Bois Club) to the Young Republicans.

In defiance of the ban, tables were set up in Sproul Plaza (previously tables had been permitted on a small strip of sidewalk at one of the campus entrances). When eight students were summoned to the Dean’s office for citations, hundreds went with them, declaring that they too had violated the rules. Draper notes that this technique would be followed throughout the FSM; when the administration tried to pick off a few leaders, supporters would show up en masse.

Chancellor Strong announced that a penalty of “indefinite suspension” was being considered against the eight. Among them was Mario Savio, a 22-year-old junior and philosophy major who had emerged as the United Front’s chief spokesperson. Savio had recently returned from a stint as a SNCC voter registration worker in Mississippi during the summer. Then on Oct.1, two deans and a campus police officer approached the Campus CORE table, which was occupied by Jack Weinberg, a former grad student in mathematics who had dropped out to be a CORE organizer. As a non-student, Weinberg was ordered to remove the table and himself from campus, and when he refused, he was arrested, a police car was summoned, and Weinberg was dragged into it. Within minutes, an impromptu sit-in by hundreds of students surrounded the car. For the next 32 hours, the police with their captive were unable to move. The police car’s roof became a makeshift speakers’ platform as first Savio and then others climbed up (after politely removing their shoes) and delivered speeches. Among the speakers were faculty members who would become harsh critics of the FSM. Sociologist Seymour Martin Lipset declared that the police car blockade was anti-democratic and immoral and told the students that, by assuming the right to break any law they didn’t like, they were acting “like the Ku Klux Klan.” Civil disobedience, he maintained, was impermissible in a “democracy” — ignoring the fact that UC was anything but a democracy.

While the sit-in was underway, a group of faculty persuaded Kerr to negotiate. An agreement was reached on Oct. 2 under which the United Front agreed to accept the decisions of a committee of administrators, faculty, and students, and the sit-in ended. Meanwhile, Kerr was under pressure to take a harder line, including from California’s Democratic governor Edmund “Pat” Brown (also known as a “liberal”), who could not understand why a massive police intervention had not been unleashed on Oct. 2.

A week later, representatives of the United Front met and constituted the Free Speech Movement. The operations of the FSM, Draper explains, were a kind of “spontaneously ordered chaos.” “Things were accomplished because hundreds of students threw themselves into the work spontaneously and somehow did it in clots of organization, with a furious amount of talk but also with overweening energy and will. Anyone could become a ‘leader,’ and the process was very simple and very visible: you led, and if you seemed to be doing any good, others followed you with a will.” This was true for Mario Savio. Draper observes that while Savio was “[n]ot a glib orator, retaining remnants of a stutter, rather tending to a certain shyness, he yet projected forcefulness and decision in action.”

An important component of the FSM was the newly-formed Independent Socialist Club (ISC). Hal Draper was a founding member, along with a few other veterans of the ISL, but most were younger people who had been in the left wing of the Young People’s Socialist League (YPSL) and identified with the Workers Party-ISL tradition. Although the ISC was never large, its leaflets and forums influenced a significant part of the campus; in the fall of 1964, and through the rest of the decade, a great many students looked to it for explanations and a Marxist political education. Within the FSM and the teaching assistants’ union, the ISC was the leading advocate of the strike tactic, as a way of involving broader layers in the movement, beyond those who were willing to take the risks of sit-ins, building occupations, and other illegal activities. Jack Weinberg and Mario Savio attended the ISC’s founding meeting. Savio never actually joined, but his speeches show the strong influence of a talk Draper gave at the ISC’s first public meeting on “Clark Kerr’s Vision of the University”; it was issued as an ISC pamphlet, “The Mind of Clark Kerr,” right after the police car blockade and is reprinted in this volume.

Draper’s talk interpreted a series of lectures Kerr had delivered at Harvard in the previous year entitled “The Uses of the University,” as well as a book he had co-authored earlier, Industrialism and Industrial Man: The Problem of Labor and Management in Economic Growth. In his lectures, Kerr coined the term “multiversity” to characterize the new form assumed by American universities in the postwar period, integrated with political, economic, and military power. The degeneration of higher education – the subordination of universities to business and government, the privileging of research over teaching, the big business of grantsmanship, vocationalization, etc. – was not explicitly celebrated by Kerr, but rather presented as inevitable.

The multiversity comes to resemble any business that creates a product – in its case, knowledge. The knowledge factory’s staff, the professoriate, increasingly resemble entrepreneurs, especially in the social and natural sciences. The university president is no longer an old-fashioned autocrat, but “the Captain of a Benevolent Bureaucracy.” Behind all this was Kerr’s vision of a Brave New World (he uses this term), resulting from the convergence of an increasingly bureaucratic capitalism with a liberalized form of Communism, which he calls simply “Industrialism,” an administrative state of managers (benevolent, naturally) ruling over the docile, cooperative masses. With all the major social and economic problems solved, there will be no protest, except for insignificant outbursts provoked by “malcontents” among the intellectuals. Intellectuals, Kerr says, “are a particularly volatile element . . . by nature irresponsible, in the sense that they have no continuing commitment to any single institution or philosophical outlook and they are not fully answerable for consequences.” But they can be “a tool as well as a danger” if used effectively by the managers.

While the FSM declared a moratorium on direct action, negotiations dragged on for weeks. Finally, on Nov. 9, the FSM, explaining that “we’ve been shuffled back and forth through the maze of the university’s bureaucracy” with no result, announced that it would once again start “exercising its constitutional rights.” This decision in favor of a return to civil disobedience was opposed by the moderates on the executive committee – mostly representatives of the Young Democrats, Young Republicans, and YPSL. Tables reappeared on Sproul Plaza, but the movement had clearly lost a good deal of its support and dynamism. Over the Thanksgiving break, however, an administration blunder managed to effect a complete turnaround. The FSM received news that Savio and three others were up for expulsion.

At a massive noon rally on Dec. 2, Savio delivered his famous speech summoning the crowd to occupy Sproul Hall. In words that show the influence of Draper’s “The Mind of Clark Kerr,” he said, “if this is a firm, and if the Board of Regents are the Board of Directors, and if President Kerr in fact is the manager, then . . . the faculty are a bunch of employees and we’re the raw material. But we’re a bunch of raw materials that don’t mean to be . . . made into any product. Don’t mean . . . to end up being bought by some clients of the University. . . . We’re human beings.” Savio then appealed to a personally-based politics of moral commitment: “There’s a time when the operation of the machine becomes so odious, makes you so sick at heart that you can’t take part, you can’t even passively take part. And you’ve got to put your bodies upon the gears and upon the wheels, upon the levers, upon all the apparatus, and you’ve got to make it stop. And you’ve got to indicate to the people who run it, to the people who own it, that unless you’re free the machine will be prevented from working at all.”

Led by Joan Baez and singing “We Shall Overcome,” 1,000-1,500 entered the administration building. Employees were sent home, and offices were used for classes, food distribution, folk singing, films (Charlie Chaplin, Laurel and Hardy), lectures on civil disobedience, and a Hanukkah service.

At the urging of Alameda County deputy district attorney Edwin Meese[3] (and behind him, Knowland), Gov. Brown ordered the biggest mass arrest in U.S. history until that time. More than 600 police, highway patrolmen, and sheriff’s deputies converged on Sproul Hall. Most of the sit-inners, following Civil Rights Movement protocol, went limp. The women were roughly thrown into elevators and taken to the basement for booking. Men, an observer reported, “were deliberately hauled down the stairs on their backs and tailbones, arms and wrists were twisted, hair and ears pulled—all to the immense amusement of the Oakland police.” After 12 hours, 800 had been arrested.

Early that morning, while the arrests were still in process, a general strike of students and faculty began. An emergency faculty meeting was called, attended by 900 professors – twice as many as the usual Faculty Senate attendance. The meeting overwhelmingly adopted a resolution in favor of new, liberalized rules for on-campus political activity, dropping all pending actions against students, prohibiting prosecution of students by the University for off-campus civil disobedience, and prompt release of the arrestees. Support also came from the head of the state Building Services Union, which represented the university’s maintenance workers, the Longshoremen’s Union, and the central labor councils of San Francisco, Alameda, and Contra Costa counties.[4] Among the teaching assistants the strike was 90 percent effective in the humanities and social sciences; unsurprisingly it was weakest in engineering and business administration. By the third, and last, day of the strike it was supported by an estimated 80 percent of the student body, some 15,000 students.

While the strike was underway, Kerr turned to one of his faculty allies, Robert Scalapino, chair of the political science department. Scalapino organized a meeting of department chairs, who tended to be more sympathetic to the administration than the average faculty member. By invoking the threat of an investigation by the State Legislature, he got the chairs to endorse a “settlement” that included only one concession to the FSM: a promise to drop disciplinary charges by the university, but not to press for withdrawal of the civil charges facing the 800 who had occupied Sproul Hall. Nor did the chairs’ proposal include lifting the restrictions on advocacy. Meanwhile a dissident caucus of 200 professors put together a resolution for the upcoming Faculty Senate meeting which substantially supported all of the FSM’s demands, notably the removal of any distinction between advocating lawful and unlawful actions. This last demand was totally unacceptable to Kerr, so in an attempt to short-circuit the initiative of the 200, he announced a special convocation of the entire university community, at which the chairs’ decision would be presented

The meeting, attended by close to 20,000, was held in the Greek Theater, a beautiful open-air amphitheater built into a hillside next to the campus. As befits the setting, a tragic drama ensued – but a tragedy for Kerr, not for the FSM. FSM leaders had asked for Savio to be included among the speakers so he could deliver a response and also announce a Sproul Plaza rally to follow the convocation. They were refused, but they had no intention accepting exclusion. With the department chairs ensconced in throne-like chairs on the stage, Kerr delivered a speech that utilized all his considerable skills to appear reasonable and statesmanlike, but was received with loud jeering.[5] Then, as the program ended, Savio strode to the microphone to make his announcement anyway. Just as he opened his mouth, two campus policemen rushed up; one put his arm around Mario’s throat, the other grabbed him in an arm-lock; he was dragged offstage. The audience was outraged, as were many of the department chairs. So after a few minutes Savio was allowed to return to the microphone, where he briefly announced the rally, concluding “Please leave here. Clear this disastrous scene, and get down to discussing the issues.”

Draper captures the essence of the Greek Theater episode with a vivid tableau: “One moment, Kerr’s soothing phrases – about ‘the powers of persuasion against the use of force,’ ‘opposition to passion and hate,’ ‘decent means to decent ends’ – were lolling on the breeze; the next minute the armed men of the state had darted out from behind the scenery to show what ‘the powers of persuasion’ concealed and what the ‘passion and hate’ were opposed to. Coming in quick succession like that, the two pictures blurred together; and there was the face of the establishment.” This highly educational drama completely discredited the chairs’ committee and swung vast numbers of hitherto hostile or ambivalent students and especially faculty to the side of the FSM.

At the subsequent rally, the FSM announced that the strike would end that night, so that the Academic Senate might meet the next day under more tranquil conditions. This conclave, attended by almost 1,000 professors, turned out to be an unqualified triumph for the FSM. The Academic Senate’s respected committee on academic freedom presented a resolution that incorporated virtually all the points advocated by the 200; it was adopted by a landslide vote of 824 to 115.

Among those who voted against the resolution was a hard core of social scientists, most of them ex-radicals, who had bitterly opposed the FSM from the beginning. Prolific article writers, they produced hostile and influential pieces that were carried by some of the leading liberal journals. The most prominent members were three sociologists, Lipset, Nathan Glazer, and Lewis Feuer, and the political scientist, Paul Seabury. Glazer and Lipset had been socialists in their youth, Feuer a Communist Party fellow traveler. Later, they emerged as prominent neoconservatives. This “ex-left” is seen by Draper as “lashing out in fury at the tragedy of their own pasts. The hatred they unleash against the radical students is a self-hatred in the first place projected against the new generation which (they think) mirrors their sad youth.”

Feuer was the most vitriolic of the group. In a series of articles in the New Leader, he denounced the FSM as a movement of “forlorn crackpots and rejected revolutionists,” “lumpen beatniks and lumpen agitators” promoting “a mélange of narcotics, sexual perversion, collegiate Castroism and campus Maoism.” Feuer was offended by the “acrid smell of the crowded, sweating, unbathed students.” Laying on a crude psychoanalytic analysis, he claimed protesting students were stuck in “a prolonged adolescence and repetitive reenactment of rebellion against their fathers.”[6] Later, in his 1969 book, The Conflict of Generations: The Character and Significance of Student Movements, Feuer deplored the New Left’s “positive advocacy of promiscuity” and “interracial sexuality.”

Right after the Christmas break, Chancellor Strong, having lost the confidence of the faculty, resigned. He was replaced as acting chancellor by the much more likeable and conciliatory Martin Meyerson. Regulations on student political activity were significantly loosened; rallies were to be permitted on the Sproul Hall steps with loudspeakers provided by the university, and the ban on fundraising and recruiting at the tables was lifted. Virtually all the goals of the FSM had been won.

But the FSM as an organized movement did not survive much longer. In March 1965 a young self-described poet, a nonstudent, came into town, stationed himself on the steps of the student union, and held up a sign inscribed with the word “FUCK.” He was arrested, and the next day a handful of students held a rally to protest the arrest and repeat the offending word. Nine were arrested, including one FSM leader, Art Goldberg.[7] Although the bulk of the FSM initially treated the controversy as trivial and a distraction, the press eagerly promoted the story that it had become a “filthy speech movement.” Then, when chancellor Meyerson banned a new campus countercultural literary magazine, Spider,[8] which had made a point of printing the “obscenity” in question, as well as many others, the FSM decided to take up what had become a genuine free speech issue and to defend the language in Spider as a legitimate form of cultural criticism. Very little support came from the student body, however, and the incident led to a serious breach with the liberal faculty, some of whom organized a noon rally of their own to denounce Spider and the FSM.

In the midst of this contretemps, Kerr, to everyone’s shock, announced his intention to resign. Draper interprets this as a power-play. Kerr had earned the enmity of the hardline faction on the Board of Regents by “capitulating” to the FSM and refusing to expel the “filthy speech” students, thereby restoring some of his liberal luster. Knowing that his move would therefore generate a surge in support among the campus community as well as the more moderate Regents, Kerr expected that threatening to resign would put him back in control. Kerr’s coup, Draper argues, together with the obscenity issue and the split with liberal faculty, created so much confusion and demoralization, that the FSM was paralyzed. Then, in April, Mario Savio suddenly announced that he was withdrawing from campus activity. Savio insisted that he was doing this to avoid dominating the movement, but it was widely believed that he was burned out. Soon after, the FSM dissolved.

The FSM was a major catalyst in the crystallization of a new, broadly based radicalism in the United States. The New Left had been coming together since 1959-60 in the form of organizations such as SDS and publications such as Studies on the Left, but in the Berkeley uprising it acquired for the first time a mass following. The radicalism of the FSM consisted not in its explicit program as much as its methods. Its goals, after all, were essentially liberal: freedom for speech and political organizing. But the FSM used disruption and civil disobedience to force the university to accede to its demands. By so doing, Draper argues, the FSM in effect rejected “permeation” in favor of “left opposition.” “The former seeks to adapt to the ruling powers and infiltrate their centers of influence with the aim of . . . becoming part of the Establishment” and moving it to the left. “The latter wish to stand outside the Establishment as an open opposition, achieving even short-term changes by the pressure of a bold alternative, while seeking roads to fundamental transformations.” Even within the FSM, there was a divide between moderates and militants, with the former inclined to adapt to the administration’s intransigence and constantly working for a deal with Kerr, while the latter planned and prepared the mass of students for civil disobedience and strikes.

“Permeation” versus “left opposition” – not peaceful methods versus violence, barricades, and so on — was and is the real essence of the distinction between reformist and revolutionary politics. In 1964-65 Draper had in mind as the leading permeationists on the left the proponents of “coalitionism” as a strategy for winning influence in the Democratic Party and the Johnson administration – Shachtman (by now a rightwing, pro-imperialist social-democrat), Bayard Rustin, Michael Harrington, Irving Howe. The coalitionists had called for a moratorium on militant civil rights actions during the summer and fall of 1964, in order to prevent a “white backlash” that would help the Republicans in the election. As the U.S. war on Vietnam escalated, they stood for critical support to Johnson’s deterrence policy, calling for negotiations rather than immediate withdrawal, a position that granted Washington the right to intervene in the first place, and would have allowed the war to continue until talks concluded (Shachtman actually became fully pro-war). Howe was initially friendly to the FSM, but as the New Left began emerging, he took to attacking it as a movement dominated by “kamikaze radicals and desperados.”[9] The FSM, Draper believed, exhibited the potential for the new radicals to resist cooptation by what Harrington called the “left wing of the possible” – that is, the left wing of the establishment.

The issue of tactics and their political implications was at the core of a debate on Jan. 9 between Draper and Nathan Glazer, organized by the ISC.[10] Draper argued that a radical leadership and strategy were essential to the FSM’s success. Glazer responded by insisting that the use of disruption and force to bring about change is never justified in a “functioning democracy” – or in a university, which, while not a democracy, was led, at Berkeley, by liberal, rational men. Draper acknowledged that Kerr “is not the villain of the piece – he is the man in the middle, who is accomplishing the hatchet work of the Right now, because they are pressing him. . . . Therefore, the answer is: let us press him in the opposite direction. Let us fight as militantly, as forcefully, with as much energy and determination, to put pressure on the man-in-the-middle by our means and for our ends as the Right is doing.”

Draper noted the new radicals’ “conscious avoidance of any radical ideology” – that is, a coherent, systematic, and democratic alternative to liberalism. New Leftists “are inclined to substitute a moral approach . . . for political analysis as much as possible.” Still, by “training and inspiring new cadres of idealistic youth with social goals so imbued with a new moral vision as to raise basic questions over the established order of society,” the New Left gave birth to one of the greatest oppositional movements in American history, the mass movement against the Vietnam War. This movement began to take shape in the winter and spring of 1965 with a national series of teach-ins on college campuses. The first took place in Ann Arbor, but Berkeley’s was by far the largest, with an attendance of 30,000. The Vietnam Day Committee organized efforts to block the troop trains that passed through the East Bay carrying soldiers to the ships bound for Vietnam. And soon came the immense antiwar marches throughout the country. FSM represented the first time radicals had led a large-scale challenge not to Southern racists or Northern reactionaries, like HUAC, but to liberals like Kerr and Brown. The New Left and the antiwar movement went on to confront Johnson, Humphrey, and the liberal Democratic Party establishment, which carried out the bloody aggression against Vietnam.

And, of course, the FSM triggered a phenomenal global wave of student radicalism. During the second half of the sixties, student revolts broke out in Berlin, Paris, Prague, Milan, Turin, London, Madrid, Warsaw, Tokyo, Mexico City, as well as dozens of American universities. In Berkeley there were huge mobilizations around Stop the Draft Week at the Oakland Induction Center, in support of a Black Studies Department on campus, demanding the release of imprisoned Black Panther Party leader Huey Newton, in defense of People’s Park (during which Gov. Reagan ordered in the National Guard, which fired on the protestors with buckshot-filled guns, killing a bystander), and other causes. During my four years as a student, a strike or a mass civil disobedience event seemed to break out almost every semester. My first tear gassing occurred at a big street demonstration in solidarity with French students in May 1968.

Such was the legacy of the FSM in the 60s.

Until his death in 1990, Hal Draper continued to write prolifically on matters of Marxist theory, history, and contemporary political events. Many of his essays, some dating back to the 30s, and transcripts of his KPFA radio talks can be found in the Marxists Internet Archive (www. marxists.org). Before the FSM, Draper had written a groundbreaking essay, “The Two Souls of Socialism,” first published in the socialist student magazine, Anvil, in 1960, then in revised form in New Politics in 1966, which introduced the concepts of “socialism from above” and “socialism from below.” He later went on to write the five-volume Karl Marx’s Theory of Revolution, a brilliant and comprehensive treatment of Marx’s ideas and political activity. Draper also edited The Complete Poems of Heinrich Heine, the nineteenth century German poet, for which he provided new translations.

For much of the period since about 1970, Berkeley, like most American universities, has been relatively quiescent politically. The campus has an FSM Café and the Mario Savio Steps, marked by a bronze plaque. Today, most people look back on the 60s with a nostalgia that has more to do with the counterculture than with radical politics. Nonetheless, it is worth remembering the last time before now that radicalism was a mass phenomenon.

What can the contemporary left learn from the FSM experience?

There is a negative lesson, something to be avoided. The FSM, like the Berkeley student body in 1964, was overwhelmingly white. The New Left too was anything but racially diverse, despite its roots in the Civil Rights Movement and the alliances it formed with black, Latino, and Native-American radical groups – such as the Panthers, Brown Berets, Young Lords, and American Indian Movement — in the late 60s. While this problem does continue to afflict socialist organizations such as DSA, in the era of Black Lives Matter a multiracial mass movement has emerged that is unlike anything seen in the 60s.

On the positive side, the FSM is a classic example of radicals successfully winning much larger numbers of political moderates and liberals to their cause through education, honesty, patient persuasion, and democratic activity. At every stage of the struggle, the FSM — by which I mean the militant majority on the executive committee – carefully explained and justified its tactics to the movement’s rank and file. At the mass trial of the Sproul Hall arrestees in July 1965, the judge, on the eve of passing sentences, asked the now-convicted defendants to submit statements explaining why they had joined the sit-in. Historian Robert Cohen writes: “Only 6 percent of those who wrote to the judge . . . articulated anything resembling a radical critique of capitalism or the university.”[11] Of course, these statements tell us what the sit-inners recalled they had been thinking seven months earlier; undoubtedly, a great many were radicalized by the arrests themselves and by subsequent events.

Today’s radicals are once again presented with the choice between permeation and left opposition, to use Draper’s terms. It proved to be the tragedy of the New Left, and a major reason for its decline and political degeneration toward the end of the 60s, that it never succeeded in developing a broad, pro-working class, radical-democratic politics – and, crucially, an independent political party – that could appeal to wider layers of the population. Those who did not succumb to various versions of neo-Stalinism and terrorism, or drop out of politics, were reabsorbed, especially by the McGovern campaign, into Democratic Party liberalism. Now, decades later, however, the mass uprising against the police and systemic racism, urgent demands for Medicare for All and a Green New Deal all point to the potential for independent political action. The grave danger is that this potential will remain unrealized, as radicals in the Progressive Democrats and Our Revolution, and much of the DSA, pursue the fantasy of transforming the Democratic Party. This is the permeationism that Draper warned against. Yet, even more than in the 60s, the U.S. left today faces the possibility of a major breakthrough. Will it limit itself to forming a powerless left-wing fringe of a party that is overwhelmingly controlled by capitalists and their political servants, or will it constitute itself as a clear left opposition? That is the question.

[1] “An End to History,” included in this volume.

[2] A former Senator, Knowland’s relentless support for Chiang Kai-shek made him known as the “Senator from Formosa” (Taiwan). His rigidly rightwing politics led even President Eisenhower to confide in his diary: “In his case, there seems to be no final answer to the question, ‘How stupid can you get?'”

[3] Meese later became Ronald Reagan’s closest advisor during both Reagan’s governorship of California and his presidency. Meese was implicated in the Iran-Contra affair and several other scandals in the 1980s.

[4] This support from labor, though important, should not be mistaken for support from rank-and-file workers, most of whom probably remained skeptical, or hostile, towards campus protests throughout the decade – even though it is known that antiwar sentiment was actually more widespread among workers than in other groups.

[5] Decades later Kerr revealed his belief that the jeering was an organized plot, coordinated by walkie-talkies.

[6] Revealingly, Michael Harrington, in his autobiography, Fragments of the Century, defended Feuer as a man who “looked at political questions with the scrupulousness of a moralist,” and thus “discovered that he could not go along with some of the more extreme demands” (which of the FSM’s demands did Harrington consider “extreme,” one wonders?). “Then, in a rather typical and miserable fashion, the students began to berate him as a sellout, an agent of the administration.” Harrington saw in the persecution of poor Feuer an “important trend in the New Left, the beginning of the game of more-militant-than-thou which was to last for four years and drive some people to the ultimate proof of their ‘radicalism’ – armed terror.”

[7] A moderate within FSM, Goldberg was also an ardent admirer of Communist China, earning him the sobriquet “Marshmallow Maoist.”

[8] The title was an acronym for sex, politics, international Communism, drugs, extremism and rock n’ roll.

[9] For a devastating takedown of one of Howe’s anti-New Left diatribes, see Draper’s “In Defense of the New Radicals,” New Politics, Summer 1965.

[10] An ISC leader, Joanne Landy, later recalled that when she invited Glazer, who was well aware of Draper’s debating skills, to participate, he said, “’Joanne, I’m not suicidal. I’m not going to do this.’ . . . Eventually he said, ‘OK, but I’m going to regret this for the rest of my life.’ The debate finally happened, and of course he got slaughtered.” Kent Worcester, “The Third Camp in Theory and Practice: An Interview with Joanne Landy and Thomas Harrison,” Left History, Vol 21, No. 2, Fall/Winter 2017/18. https://newpol.org/third-camp-theory-and-practice-interview-joanne-landy-and-thomas-harrison.

The text of the debate was published in New Politics, Winter 1965, “The FSM: Freedom Fighters or Misguided Rebels?”

[11] Robert Cohen and Reginald E. Zelnik, eds, The Free Speech Movement: Reflections on Berkeley in the 1960s. Berkeley 2002.

This article was written for L’Anticapitaliste, the weekly newspaper of the New Anticapitalist Party (NPA) of France.

This article was written for L’Anticapitaliste, the weekly newspaper of the New Anticapitalist Party (NPA) of France.

Book Review

Book Review

Thinking a socialist future implies imagining what this future might look like, and then asking how we can get there. Utopia, as conceived by revolutionary theory, implies a pragmatic aspect relating to the question of transition. Transition is a challenge. History has shown that it is not linear: no direct path leading from one point to another exists. Instead, we need to consider transition as a process. Feminist body politics aimed at dismantling rigid norms of gender and sexuality show that revolutions take time. The temporal space created by this, however, opens up a field for exploration and experimentation, a terrain on which contradictory forces clash. Is it possible to walk such a transitional path without knowing where it will lead?

Thinking a socialist future implies imagining what this future might look like, and then asking how we can get there. Utopia, as conceived by revolutionary theory, implies a pragmatic aspect relating to the question of transition. Transition is a challenge. History has shown that it is not linear: no direct path leading from one point to another exists. Instead, we need to consider transition as a process. Feminist body politics aimed at dismantling rigid norms of gender and sexuality show that revolutions take time. The temporal space created by this, however, opens up a field for exploration and experimentation, a terrain on which contradictory forces clash. Is it possible to walk such a transitional path without knowing where it will lead?

The sharp disagreement that arose earlier this summer, when the NYC Lower Manhattan branch of the Democratic Socialists of America’s (DSA) extended a speaking invitation to Adolph Reed, was both telling and politically significant. According to The New York Times, the Black academic was intending to argue that “the left’s intense focus on the disproportionate impact of the coronavirus on Black people undermined multiracial organizing, which he sees as key to health and

The sharp disagreement that arose earlier this summer, when the NYC Lower Manhattan branch of the Democratic Socialists of America’s (DSA) extended a speaking invitation to Adolph Reed, was both telling and politically significant. According to The New York Times, the Black academic was intending to argue that “the left’s intense focus on the disproportionate impact of the coronavirus on Black people undermined multiracial organizing, which he sees as key to health and

Book Review

Book Review

When COVID-19 – a pandemic caused by a pathogen that sprouted from the very conditions through which our capitalist societies produce food and deal with nature – was announced as a reality in Rio de Janeiro on March 13th, our concerns were focused on growing police killings, lack of water in various working-class neighborhoods, and an increasing unemployment rate at a national level of 12.2% (around 12.9 million of people), this in a labor market where informal work comprises as much as 41% of all workers and where many of the unemployed are therefore not counted.

When COVID-19 – a pandemic caused by a pathogen that sprouted from the very conditions through which our capitalist societies produce food and deal with nature – was announced as a reality in Rio de Janeiro on March 13th, our concerns were focused on growing police killings, lack of water in various working-class neighborhoods, and an increasing unemployment rate at a national level of 12.2% (around 12.9 million of people), this in a labor market where informal work comprises as much as 41% of all workers and where many of the unemployed are therefore not counted.

In my counter-historical novel

In my counter-historical novel

Donna Murch talked with Sherry Wolf, author of Sexuality and Socialism, in July 2020, in the midst of the uprising against the police murder of George Floyd.

Donna Murch talked with Sherry Wolf, author of Sexuality and Socialism, in July 2020, in the midst of the uprising against the police murder of George Floyd.

Source:

Source:

As expected, the extremely dubious electoral procedure, misnamed “elections”, caused mass indignation among the citizens of the Republic of Belarus to which the authorities have responded with widespread violence and repression against many protesters.

As expected, the extremely dubious electoral procedure, misnamed “elections”, caused mass indignation among the citizens of the Republic of Belarus to which the authorities have responded with widespread violence and repression against many protesters.

“By the late 1990s,” the organizer Jane McAlevey recalled, “I sat through numerous sessions where well-known national pollsters instructed labor leaders to replace the word working class with middle class.” Soon many labor leaders needed little reminding. Nevertheless, McAlevey’s point that the language of “saving the middle class” gained traction through electoral politics stands and her mention of the 90s nails the periodization. Earlier electoral appeals to the middle class had worked locally, mostly in the context of right-wing anti-tax and anti-integration initiatives, but it was the Bill Clinton victories during the 90s that made those appeals national and bipartisan. His pollster, Stanley Greenberg, famously made “middle class dreams” the key to progressive electioneering. The understanding of race and of class in political debates and among social movements has suffered for it.

“By the late 1990s,” the organizer Jane McAlevey recalled, “I sat through numerous sessions where well-known national pollsters instructed labor leaders to replace the word working class with middle class.” Soon many labor leaders needed little reminding. Nevertheless, McAlevey’s point that the language of “saving the middle class” gained traction through electoral politics stands and her mention of the 90s nails the periodization. Earlier electoral appeals to the middle class had worked locally, mostly in the context of right-wing anti-tax and anti-integration initiatives, but it was the Bill Clinton victories during the 90s that made those appeals national and bipartisan. His pollster, Stanley Greenberg, famously made “middle class dreams” the key to progressive electioneering. The understanding of race and of class in political debates and among social movements has suffered for it.