Subcomandante Marcos: The Last Global Ethical Hero?

Book Review

Book Review

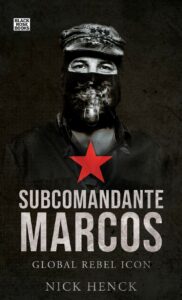

Nick Henck. Subcomandante Marcos: Global Rebel Icon. Montreal: Black Rose Books, 2019. 152 pages. Appendix. Bibliography. Notes.

Nick Henck ends his latest book on Subcomandante Marcos, the leader of the Zapatista Army of National Liberation, with this remark, “…the Subcomandante may well be the sole surviving globally recognized (and recognizable) ethical hero of iconic stature.” Henck had explained to us earlier the Sub had recognized that a cult of personality had developed around him and that the Sub rejected it and that to fend it off Marcos had changed his name to Galeano. Undeterred, Henck continues to burn incense on the altar of the Marcos cult. And he seldom calls him Galeano.

Nick Henck, a law professor at Keio University in Tokyo, Japan and the author of no fewer than four books and many articles on Subcomandante Marcos, the leader and spokesperson of the EZLN that in January 1994 lad an uprising in the southernmost state of Mexico. Henck’s first book on Marcos Subcommander Marcos: The Man and the Mask, a 500-page biography published in 2007. In 2017 he published Insurgent Marcos: The Political-Philosophical Formation of the Zapatista Subcommander, a study of the intellectual formation of Marcos and of his writing. Two years ago he published The Zapatistas’ Dignified Rage: Final Public Speeches of Subcommander Marcos, which is described in its title. And now we have the new book Subcomandante Marcos: Global Rebel Icon, a short updated biography.

If you want a handy little book of just 100 pages that reads like a long Wikipedia article providing all the dates, names, and events, this is your book. If you want a discussion of Marcos’ ideas and his role in Mexican political life and in the global left, comparing and contrasting him and his politics with those of others, you will be disappointed.

The new book—just 100 pages really—shares the same faults as the great big biography that he published and which I criticized thirteen years ago. Once again we have a book that is primarily a chronicle of the life and activities of Marcos, though not in the excruciating detail of the earlier biography. The same problems that I described earlier still exist. As I wrote then:

Henck does not locate Marcos in the history of modern Mexico, nowhere discusses the significance of the Mexican revolution (1910-20) and its successes and failure, and never describes the politics of the Institutional Revolutionary Party, the National Action Party and the Party of the Democratic Revolution, all of which the Sub has had to contend with.

Marcos and the Zapatistas are not put in the context of the guerrilla tradition in Mexico from Zapata to Lucio Cabañas, nor are they contrasted with Cardenismo from Lázaro Cárdenas to his son Cuauhtémoc. While the author constantly refers to Che Guevara, Guevara’s politics and their significance is never discussed.

The one point that is mentioned several times, but never developed, is that Marcos gave up the orthodox Marxism-Leninism of most Latin American guerrillas for his supposed subordination to the will of the indigenous people, the Maya of Chiapas. Yet this book never discusses the history of the indigenous in Mexico, or the Mexican state’s official theory of indigenismo, nor the other existing, cooperating and competing indigenous trends.

What does it mean to be part of an Indian movement? One might have made allusions to the indigenous movements of Bolivia and Ecuador by way of comparison to elucidate what is unique about zapatismo.

As with the earlier biography, in this new one we never see Marcos in the political context. We still have no explanation of why Marcos during The Other Campaign in 2006 marched along with a political party that carried and displayed at rallies portraits of Joseph Stalin. Why would the EZLN—even if they did not support any of the political parties or candidates that year—not join with others to protest election fraud? We never see him and the EZLN in relationship to the old parties or to MORENA, the Movement for National Regeneration Party of President Andrés Manuel López Obrador.

I’m afraid I have to write about this book what I wrote about the earlier biography: “Henck’s book is principally chronology and secondarily hagiography. The author is not simply an admirer of Marcos; he adulates him as a genius, an inspiration and the direction of the future.”

Marcos certainly became a global hero when he led the Zapatista Army of National Liberation (EZLN) in the Chiapas Rebellion in 1994, and he remained renowned worldwide throughout the 1990s and into the 2000s. But is Subcomandante Marcos the last global ethical hero? What about Greta Thunberg, the 15-year old girl who in August of 2018 stood outside the Swedish parliament with a sign reading Skolstrejk för klimatet (School strike for climate) until gradually a movement assembled around her first in Europe and then in other countries around the world as students struck to protest climate change and demand system change.

Or how about Li Wenliang, the Chinese doctor who tried to warn other physicians about the Chinese coronavirus outbreak and then died after contracting the virus while treating patients in Wuhan? Or what about the collective and often anonymous leaders of the Hong Kong pro-democracy protests? Or of the Yellow Vests movement in France? Or those leading the revolutionary movements in Algeria? Or in Sudan? Or of the pro-democracy protests in Belarus today? Perhaps Marcos is the last of a certain type of ethical leader, the guerrilla poet savior, but maybe today, 25 years since the EZLN Chiapas uprising, we need a new type.