“Dirty Break” for Independent Political Action or a Way to Stay Stuck in the Mud?

“Dirty Break” for Independent Political Action or a Way to Stay Stuck in the Mud? was written in response to an article by Eric Blanc that appeared on the Jacobin website in December 2017. Blanc’s article concerned the formation of the Minnesota Farmer Labor (MFLP) Party in 1922. Blanc argues that organized labor in Minnesota, under socialist leadership, ran in major party primaries in the 1920 election cycle, presumably for the purpose of gaining electoral support, prior to breaking and forming the MFLP. This, he argues, was a “dirty break” as compared to a clean break which would have avoided the major party primaries altogether. The purpose of Blanc’s article was to propose a similar “dirty break” approach to electoral political today by running in Democratic primaries with the idea of eventually breaking to form an independent working class-based party at some point in the future. This “dirty break” has since gained popularity within DSA. I have written extensively in New Politics, on the Jacobin website, and in books about why I think pursuing electoral action through the Democratic Party is a dead end or worse. I wrote this critique of Blanc’s article for the Jacobin website in 2018 because I thought his arguments were original enough to demand a response. Although a rebuttal from Blanc was promised, Jacobin has yet to publish my article after two years. So, I thank New Politics for putting this up on their website.

– Kim Moody, June 10, 2020

Although the union-backed Working People’s Non Partisan League (WPNL) ran statewide candidates in the major party primaries in the 1920 elections, as Eric Blanc reports, “In the cities, where local electoral rules removed the need to run in primaries in the first place, the union-based WPNPL (Working People’s Non Partisan League) ran an independent slate of ‘Labor Candidates’ against Republicans and Democrats alike.” Since they didn’t have to run as independents, this points to a political desire to do so, a desire to break from the major parties, which they did in the next election round, while the primarily farmer-based Nonpartisan League (NPL) didn’t. And since, as Blanc argues, organized labor would become the organizational and financial backbone of the Farmer-Labor Party (FLP), the secret of its eventual success, it seems the scenario of major party primaries as a building block for the FLP is only one part of the story, perhaps not the most important part, and perhaps even a drag on the process of breaking with the old parties. The left-wing of urban labor made a break in practice in 1920, even as the rural wing of the movement didn’t, well before the FLP was formed. This, as we will see below, was a reflection of the division between the NPL and the labor party movements nationally in this period.

The importance of the “dirty break” interpretation of the history of the FLP appears to be that it holds a precedent for today. Run or support candidates in the Democratic Party primaries and then you will have the forces to make a break—a neat two-stage strategy. Given the differences in the level of organization, funding, and professionalism of today’s state parties from those of the 1920s, the analogy is questionable, as I will argue below. Nevertheless, what is clear in Blanc’s account is that the NPL’s overall “inside-outside” strategy, as some would call it today, did not work in electoral terms in Minnesota. That is, as long as it ran “inside” the major party primaries it lost elections. Furthermore, the major parties grew tired of having their primaries invaded by candidates who refused to remain loyal to the party once they lost. So, in 1921 they passed a state law prohibiting those who ran in a major party primary and lost from subsequently running as an independent or candidate of another party. The “inside-outside” strategy not only failed in Minnesota, it was foreclosed. What next?

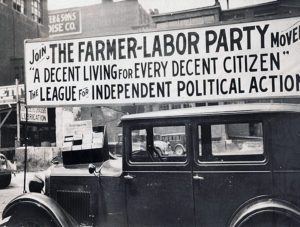

After the 1920 elections, as Blanc reports, socialist William Mahoney and his supporters in the unions, abandoned the failed strategy, which he had apparently gone along with (the “dirty” part) and led the organization of an independent FLP backed by the unions and with the support of some NPL farmers in 1922, something Mahoney said he had wanted all along. In that year they made the break complete (clean?), rejecting a fusion-type alliance with the Democrats and forming a party that would run its own candidates. Eventually they turned this party into “a well-structured, mass workers party,” as Blanc writes, with organizational and financial backing from the unions—a classic labor party. In the 1922-23 midterm elections the FLP elected a US Senator and Congressman. The new independent strategy was working and the FLP went on to become the state’s “second party,” as one the FLP militants Blanc quotes put it until 1948 when it merged with the Democrats.

A Look Back at the Farmer-Labor Party Movement

To put Mahoney and Minnesota in context we need to look at the national farmer-labor party movement of the post-WWI years. This movement arose from the conditions of the time: the enormous strike wave and rise of union militancy in 1918-1919, general strikes in Seattle and Winnipeg, the break-up of the Socialist Party, a vicious employers’ offensive, and a recession in 1920-21. It could not have happened if hundreds of thousands of workers had not taken to the streets and workplaces of the US in opposition to capital’s post-war offensive. This movement for a labor or farmer-labor party was part of the international worker upsurge of strikes and revolutionary actions that followed WWI. In the US it received inspiration from the Russian Revolution, that in Germany, and above all the growth of the British Labour Party.

From 1918 to 1923 the center of this movement in the US was the Chicago Federation of Labor (CFL), which labor historian Sidney Lens called “the hub of the labor movement at that time” and Philip Foner called “the hub of the labor party effort.” In 1918 the CFL led the formation of a Chicago and state-wide Illinois farmer-labor party with significant union backing in the wake of the huge, but unsuccessful meatpacking strike. While its initial electoral ventures were not very successful, it nonetheless set the tone of the national movement by opposing endorsement for or by either of the major parties, the so-called “Chicago Program”—a clean break strategy. Like most such developments in history the broader national movement was messy with plenty of factionalism, splits, failures, and successes. Nevertheless, by 1919 there were independent labor or farmer-labor parties in a dozen states and by the following year in 23 states. Minnesota was behind the learning curve.

The national movement was backed in many states by progressive union leaders, members and former members of the Socialist Party like Mahoney, a little later by the Communist (aka Workers’) Party (CP) which jumped on the band wagon in 1922, and many of the important unions in manufacturing—the centers of Socialist, Communist, and “militant minority” strength—though not for the most part in construction and transport, which were bastions of “pure-and-simple” unionism. The idea of a labor party completely independent of the major parties was also put forth by the CP-backed, rank and file-based Trade Union Educational League (TUEL) inside the AFL beginning in 1922. The TUEL, which advocated industrial unionism via amalgamation of craft unions, had a large presence in several unions and influence far beyond those between its launch in 1920 and 1923 when CP sectarianism derailed this promising rank and file-based organization. In other words, from 1918 through 1922-23 there was a large movement within the broader labor movement and upsurge for a “clean” break.

There was also, at that time, the Conference for Progressive Political Action (CPPA), which also had support from the NPLs, some union leaders, and even some FLP leaders, but mostly favored the “nonpartisan” approach of running in the major parties, which muddied the waters. Mahoney was one of those who fought within the CPPA for an independent direction.

The Minnesota labor leaders around Mahoney were, thus, part of that broader movement and favored a break with the major parties. In the formative period of the FLP, in 1922, Mahoney worked with the Communists. When, in 1923, Mahoney proposed that the Minnesota FLP host a meeting to discuss creating a national FLP, there was a weak turnout from the unions and Mahoney argued against the Communists’ proposal for an immediate launch of a national FLP, most likely correctly, on the grounds that this was premature. In any case such a move was side-lined by the 1924 Progressive Party presidential campaign of Robert LaFollette, who won 5 million votes. The recession and the employers’ offensive saw union membership plummet from its highpoint in 1920 of just over 5 million to 3.6 million in 1923. This, of course, was a major factor in undermining the movement for a labor party in the 1920s.

During these years the mostly farmer-based Non-Partisan Leagues and their national organization grew from 188,000 members in 1918 to 235,000 at its height in 1920. The NPL pursued the “nonpartisan” major party primary strategy everywhere it had strength, mostly in the Great Plains and upper Midwest. In its birthplace, North Dakota, where farmers greatly outweighed workers, the NPL had considerable success in electing its candidates in both the Republican and Democratic state-level parties—one reason why North Dakota did not develop a farmer-labor party. Had the Minnesota NPL been more successful in this strategy there might never have been a FLP in that state.

Most of the NPL leaders who followed NPL founder Arthur Townley from North Dakota, opposed the formation of an independent farmer-labor party everywhere, including, as Blanc points out, in Minnesota. Despite their growth, politically in this context they were the major grassroots opponents of independent political action, not its predecessors. The minority of labor NPL affiliates, such as that in Minnesota, generally favored a farmer-labor party, according to Foner. Hence, the independent labor candidates of 1920. In Minnesota the farmer-based NPL and its strategy were probably a factor in that state’s delay in completing the break it had started in 1920. In other words, there were two, slightly overlapping, sometimes allied movements, which represented different social bases and presented opposed political strategies.

Was the 1922 break in Minnesota clean or dirty? While Mahoney and other socialists who had generally supported the SP before the war temporarily embraced the “nonpartisan” strategy after the war, “in a great emergency” as Mahoney put it, my interpretation is that the 1922 break was a clean break with the past NPL practice of running in major party primaries. The new FLP did not run candidates in the major party primaries as far as I know. Blanc’s view is that it was “dirty” because the movement had built strength during the failed NPL strategy of running in the primaries. You choose.

The point I get from this history, however, is that the old “non-partisan” strategy failed and the majority of the movement made a break from the muddy past by 1922, following the precedent set by the Minnesota urban unions in 1920, that in Chicago and Illinois earlier, and the farmer-labor parties in other states formed before that in Minnesota. It did this, in other words, in the context of a broader labor-based movement for a complete break with the old parties and the formation of a labor party. In this it opposed the forces, mostly in the NPL and CPPA, that pushed for continued work in the major parties despite some overlap in membership. Had there not been a large labor-based movement for a clean break, it is doubtful the NPL’s “inside-outside” phase of the Minnesota movement would have gone anywhere. Minnesota labor’s 1922 break seems pretty clear and clean to me.

Indeed, concerning the “nonpartisan” strategy of the NPL, Blanc himself argues “Had there not been a sufficiently principled and influential political current willing to push back against these intense external and internal pressures, the farmer-labor party movement would have been absorbed back into the two-party system in 1922.” Agreed! So, why the positive emphasis on the NPL’s major party primary strategy and the alleged “dirty break?”

For farmers, the NPL was only the latest in a series of such organized political efforts, going back to the Grangers of the 1870s and 1880s and the Farmers’ Alliances of the late 1880s and 1890s, both of which tried to work through the major parties in the states where they had strength. The Grangers never broke from this. The Farmers’ Alliance, on the other hand, became the major base of populism and the People’s Party of the 1890s. In this latter case, the break was made, if only for a few years. The failure of the People’s Party by 1896, just 21 years before the formation of the NPL, probably influenced the NPL leaders of the post-WWI period against another third party attempt.

For labor from the mid-1880s, after the failure of the labor party movement of that period due to the collapse of the Knights of Labor, the unions of the new AFL typically engaged in “nonpartisan” major party electoral and legislative action through the city-based central labor councils and the state federations of labor. This labor version of the “nonpartisan” strategy was the policy of Samuel Gompers and the “pure-and-simple” wing of the AFL—not a means to a future break. So, the prior period of working through the major parties was not some Minnesota aberration, but the norm.

It was generally the socialists of various stripes who led the push away from this norm for a labor-populist alliance in the 1890s, the formation of the Socialist Party in 1901, and the farmer-labor parties after WWI. The scenario of socialists leading the fight for independent political action to make a break with the older practice of working through the major parties was also the norm for the post-war period. It was no accident that it was those with experience in, and commitment to, independent working-class politics through the Socialist Party (SP) who often led the movement for a farmer-labor party once the SP had declined and splintered in the post WWI period.

Minnesota was not an exception. Rather, it was the disillusionment with and opposition to the NPL strategy, not its advocacy, that allowed socialists and left labor leaders and activists to draw others into a break in two dozen states. They had to make a choice between the two directions for the movement. In American politics, by definition, there is always a prior ”dirty” phase of captivity in one or another major party or there would be nothing to break from. But he decisive force, as Blanc indicates, wasn’t those advocating the “inside-outside” “nonpartisan” strategy, but those calling for and organizing a clean break with that approach.

The Lesson for Today

The lesson for today is clear: there has to be a significant pole fighting for a clean break if those attempting to work (in any way, with or without illusions) within the Democratic Party framework are to be drawn to a political break with that party. The social, economic, and political forces within the Democratic Party today, and the national spoiler effect to which they are so attuned, make a sui generis internally-based split a virtual impossibility. (See Kim Moody, “From Realignment to Reinforcement”, updated in the Verso e-book Socialist Strategy and Electoral Politics.)

Furthermore, the idea of a tendency that juggles both strategies simultaneously by advocating a “dirty” phase and only projecting a break somewhere in the future is a recipe for confusion and delay in actually making the break, if indeed it ever happens. In any case, it is not justified by the Minnesota NPL/FLP case where a break became possible because there was a labor-based tendency that fought for such a break. Furthermore, the “dirty break” approach does not overcome the spoiler effect that keeps people voting Democratic, and Democratic office holders loyal to the party’s caucus in state legislatures and Congress, because any split in the Democratic ranks or among its office holders will throw things to the Republicans—unless the socialist have taken over the entire Democratic Party (and it has a majority), in which case it tuns out the “realigners” were right all along.

As to the city election rules that made independent labor candidates easier in Minnesota, I would argue that in today’s cities across the US there are few Republicans in limited election districts and hence little or no spoiler effect. Look at any electoral map of the US and you will see that the cities are blue and the countryside red, with the suburbs contested territory. Thus, in cities it is possible to by-pass the Democratic primaries in order to establish a “second party,” even if it loses elections for some time, if there is grassroots organization, and if there is a social base—this latter being the real question for socialist or “progressive” electoral action today. Unfortunately, we are not (yet?), despite some hopeful signs, in a period of mass upsurge such as spawned the FLP movement in the US and more revolutionary events abroad in the years following the First World War.

Is there any evidence that running in Democratic primaries builds a social base for a break in today’s circumstances or at any time in the last half century or more? After all, socialists and union members have been running in Democratic primaries for some time. The AFL-CIO notes from time to time that hundreds of its members run for office, almost exclusively as Democrats, but we see no “regenerated labor movement” from that activity. Blanc argues that the “mass workers’ organizations” have the power to overcome co-optation by the Democrats, but since their leaders do not even dream of using that power for this purpose or even to impose the policies of the movement on the Democrats, this remains a non sequitur. The US labor leadership in entirely the captive of the Democratic Party. With a few possible exceptions, they will not lead a break. This appears to be the “dirty” or “inside-inside” strategy de jour. And it is unlikely they would abandon it unless there was a strong political pole of attraction working in the labor and social movements to demand a clean and clear break with the Dems, starting in the cities and states.

Even with Blanc’s more positive interpretation, what does the Minnesota case tell us about today’s situation when the primaries are drenched in business and wealthy-donor organization and money to an extent unknown in the 1920s, and both national and state Democratic Parties are far better organized, (business) funded, professionally staffed, and disciplined in legislative votes than in the early 1920s or even the 1960s, and hence better able to repel or absorb dissident “progressives” as they have for decades. Or when scores of socialists and other leftists run in Democratic primaries with no idea of running as independents. And, most tragically, when there is no significant organized “influential political current” or pole demanding a clean break to attract labor and social movement activists. Unfortunately, it appears that Bernie, who is now focused entirely on electing Democrats, including Biden, will not be our William Mahoney.

Isn’t it the job of socialists to help build an active mass social base, a “militant minority”, through work in the unions, workplaces, and social movements, on the one hand, and a clear political pole for independent political action that can attract activists, on the other hand, as Blanc states? Wouldn’t it be a big step forward if DSA, or at least a majority of it, composed such a clear political pole of attraction within the labor and social movements, instead of being stuck in the mud of the “inside-outside” treadmill in which there is no actual “outside”?