In the age of COVID-19, it’s even more obvious than it’s been for at least a couple of decades that capitalism is entering a long, drawn-out period of unprecedented global crisis. The Great Depression and World War II will likely, in retrospect, seem rather minor—and temporally condensed—compared to the many decades of ecological, economic, social, and political crises humanity is embarking on now. In fact, it’s probable that we’re in the early stages of the protracted collapse of a civilization, which is to say of a particular set of economic relations underpinning certain social, political, and cultural relations. One can predict that the mass popular resistance, worldwide, engendered by cascading crises will gradually transform a decrepit ancien régime, although in what direction it is too early to tell. But left-wing resistance is already spreading and even gaining the glimmers of momentum in certain regions of the world, including—despite the ending of Bernie Sanders’ presidential campaign—the reactionary United States. Over decades, the international left will grow in strength, even as the right, in all likelihood, does as well.

In the age of COVID-19, it’s even more obvious than it’s been for at least a couple of decades that capitalism is entering a long, drawn-out period of unprecedented global crisis. The Great Depression and World War II will likely, in retrospect, seem rather minor—and temporally condensed—compared to the many decades of ecological, economic, social, and political crises humanity is embarking on now. In fact, it’s probable that we’re in the early stages of the protracted collapse of a civilization, which is to say of a particular set of economic relations underpinning certain social, political, and cultural relations. One can predict that the mass popular resistance, worldwide, engendered by cascading crises will gradually transform a decrepit ancien régime, although in what direction it is too early to tell. But left-wing resistance is already spreading and even gaining the glimmers of momentum in certain regions of the world, including—despite the ending of Bernie Sanders’ presidential campaign—the reactionary United States. Over decades, the international left will grow in strength, even as the right, in all likelihood, does as well.

Activism of various practical and ideological orientations is increasingly in a state of ferment—and yet, compared to the scale it will surely attain in a couple of decades, it is still in its infancy. In the U.S., for example, “democratic socialism” has many adherents, notably in the DSA and in the circles around Jacobin magazine. There are also organizations, and networks of organizations, that consciously repudiate the “reformism” of social democracy, such as the Marxist Center, which disavows the strategy of electing progressive Democratic politicians as abject “class collaboration.” Actually, many democratic socialists would agree that it’s necessary, sooner or later, to construct a workers’ party, that the Democratic Party is ineluctably and permanently fused with the capitalist class. But the Marxist Center rejects the very idea of prioritizing electoral work, emphasizing instead “base-building” and other modes of non-electoral activism.

Meanwhile, there are activists in the solidarity economy, who are convinced it’s necessary to plant the institutional seeds of the new world in the fertile soil of the old, as the old slowly decays and collapses. These activists take their inspiration from the recognition, as Rudolf Rocker put it in his classic Anarcho-Syndicalism, that “every new social structure makes organs for itself in the body of the old organism. Without this preliminary any social evolution is unthinkable. Even revolutions can only develop and mature the germs which already exist and have made their way into the consciousness of men; they cannot themselves create these germs or generate new worlds out of nothing.” The Libertarian Socialist Caucus of the DSA is one group that identifies with this type of thinking, but there are many others, including the Democracy Collaborative, the Democracy at Work Institute (also this one), Shareable, and more broadly the New Economy Coalition. Cooperation Jackson has had some success building a solidarity economy in Jackson, Mississippi.

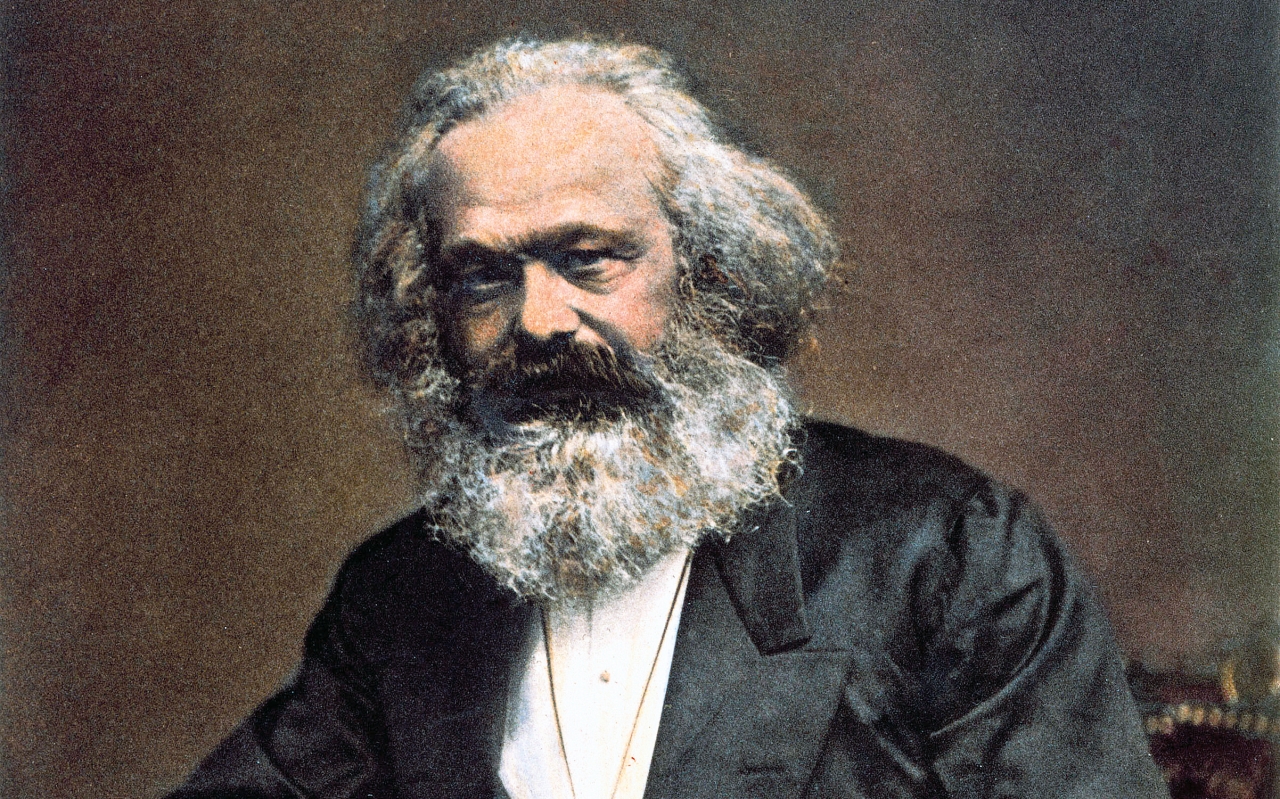

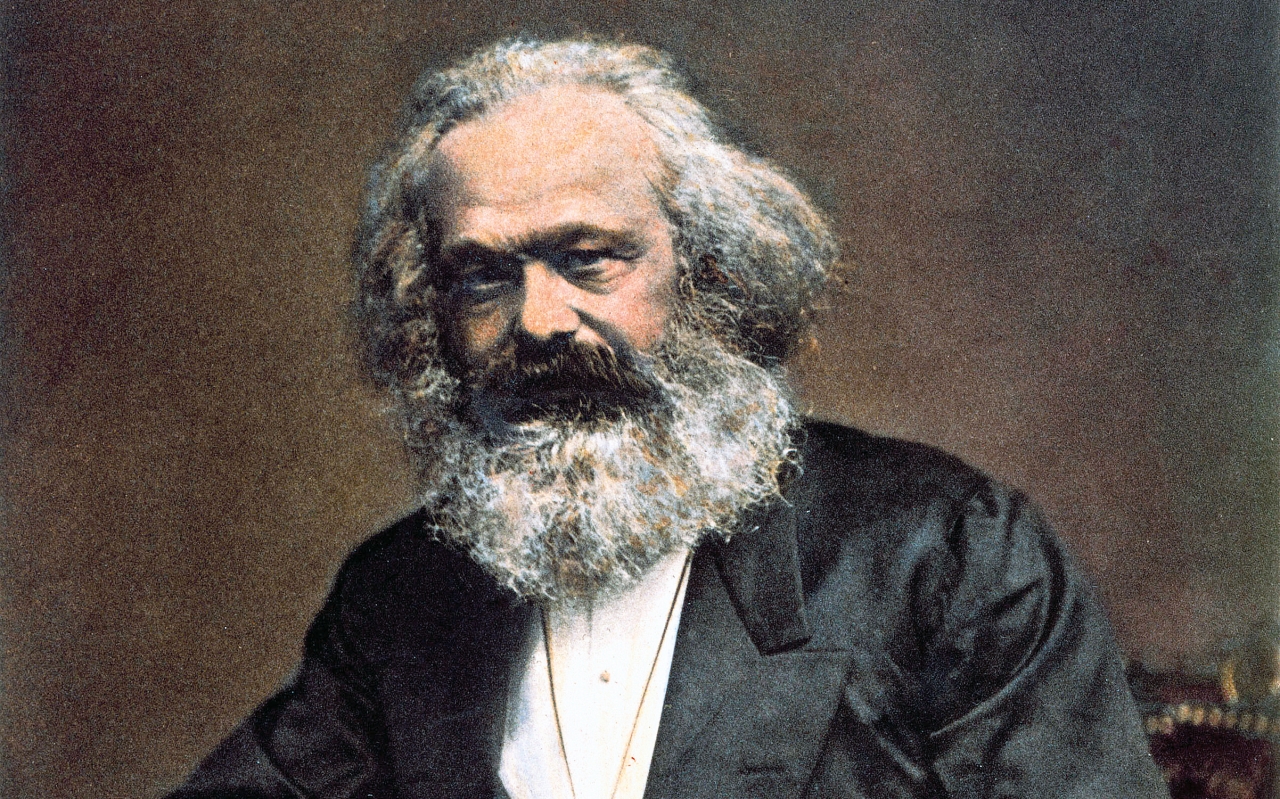

The numbers and varieties of activists struggling to build a new society are uncountable, from Leninists to anarchists to left-liberals and organizers not committed to ideological labels. Amidst all this ferment, however, one thing seems lacking: a compelling theoretical framework to explain how corporate capitalism can possibly give way to an economically democratic, ecologically sustainable society. How, precisely, is that supposed to happen? Which strategies are better and which worse for achieving this end—an end that may well, indeed, seem utopian, given the miserable state of the world? What role, for instance, does the venerable tradition of Marxism play in understanding how we might realize our goals? Marx, after all, had a conception of revolution, which he bequeathed to subsequent generations. Should it be embraced, rejected, or modified?

Where, in short, can we look for some strategic and theoretical guidance?

In this article I’ll address these questions, drawing on some of the arguments in my book Worker Cooperatives and Revolution: History and Possibilities in the United States (specifically chapters 4 and 6).[1] As I’ve argued elsewhere, historical materialism is an essential tool to understand society and how a transition to some sort of post-capitalism may occur. Social relations are grounded in production relations, and so to make a revolution it is production relations that have to be transformed. But the way to do so isn’t the way proposed by Marx in the Communist Manifesto, or by Engels and Lenin and innumerable other Marxists later: that, to quote Engels’ Anti-Dühring, “The proletariat seizes state power, and then transforms the means of production into state property.” Or, as the Manifesto states, “The proletariat will use its political supremacy to wrest, by degree, all capital from the bourgeoisie, to centralize all instruments of production in the hands of the State, i.e., of the proletariat organized as the ruling class.”

Instead, the revolution has to be a gradual and partially “unconscious” process, as social contradictions are tortuously resolved “dialectically,” not through a unitary political will that seizes the state (every state!) and then consciously, semi-omnisciently reconstructs the economy from the top down, magically transforming authoritarian relations into democratic ones through the exercise of state bureaucracy. In retrospect, this idea that a “dictatorship of the proletariat” will plan and direct the social revolution, and that the latter will, in effect, happen after the political revolution, seems incredibly idealistic, unrealistic, and thus un-Marxist.

I can’t rehearse here all the arguments in my book, but I’ve sketched some of them in this article. In the following I’ll briefly restate a few of the main points, after which I’ll argue that on the basis of my revision of Marxism we can see there is value in the many varieties of activism leftists are currently pursuing. No school of thought has a monopoly on the truth, and all have limitations. Leftists must tolerate disagreements and work together—must even work with left-liberals—because a worldwide transition between modes of production takes an inordinately long time and takes place on many different levels.

I’ll also offer some criticisms of each of the three broad “schools of thought” I mentioned above, namely the Jacobin social democratic one, the more self-consciously far-left one that rejects every hint of “reformism,” and the anarchistic one that places its faith in things like cooperatives, community land trusts, mutual aid, “libertarian municipalism,” all sorts of decentralized participatory democracy. At the end I’ll briefly consider the overwhelming challenge of ecological collapse, which is so urgent it would seem to render absurd, or utterly defeatist, my insistence that “the revolution” will take at least a hundred years to wend its way across the globe and unseat all the old social relations.

Correcting Marx

Karl Marx was a great genius, but even geniuses are products of their environment and are fallible. We can hardly expect Marx to have gotten absolutely everything right. He couldn’t foresee the welfare state or Keynesian stimulation of demand, which is to say he got the timeline for revolution wrong. One might even say he mistook the birth pangs of industrial capitalism for its death throes: a global transition to socialism never could have happened in the nineteenth century, nor even in the twentieth, which was the era of “monopoly capitalism,” state capitalism, entrenched imperialism, the mature capitalist nation-state. It wasn’t even until the last thirty years that capitalist relations of production fully conquered vast swathes of the world, including the so-called Communist bloc and much of the Global South. And the logic of historical materialism suggests that capitalist globalization is a prerequisite to socialism (or communism).

All of which is to say that only now are we finally entering the era when socialist revolution is possible. The earlier victories, in 1917, 1949, 1959, and so on, did not achieve socialism—workers’ democratic control of the economy—and, in the long run, could not have. They occurred in a predominantly capitalist world—capitalism was in the ascendancy—and were constrained by the limits of that world, the restricted range of possibilities. Which is doubtless why all those popular victories ended up in one or another form of oppressive statism (or else were soon crushed by imperialist powers).

If Marx was wrong about the timeline, he was also wrong about his abstract conceptualization of how the socialist revolution would transpire. As he put it in the Preface to A Contribution to the Critique of Political Economy, “At a certain stage of development, the material productive forces of society come into conflict with the existing relations of production… From forms of development of the productive forces these relations turn into their fetters. Then begins an era of social revolution.” The notion of fettering, despite its criticism by exponents of Analytical Marxism as being functionalist and not truly explanatory, is useful, but not in the form it’s presented here. For to say that relations of production fetter productive forces (or, more precisely, fetter their socially rational use and development) is not to say very much. How much fettering is required for a revolution to happen? Surely capitalism has placed substantial fetters on the productive forces for a long time—and yet here we all are, still stuck in this old, fettered world.

To salvage Marx’s intuition, and in fact to make it quite useful, it’s necessary to tweak his formulation. Rather than some sort of “absolute” fettering of productive forces by capitalist relations, there is a relative fettering—relative to an emergent mode of production, a more democratic and socialized mode, that is producing and distributing resources more equitably and rationally than the capitalist.[2]

A parallel (albeit an imperfect one) is the transition from feudalism to capitalism. Feudal relations certainly obstructed economic growth, but it wasn’t until a “competing” economy—of commercial, financial, agrarian, and finally industrial capitalism—had made great progress in Western Europe that the classical epoch of revolution between the seventeenth and nineteenth centuries burst onto the scene. Relative to capitalism, feudalism was hopelessly stagnant, and therefore, once capitalism had reached a certain level of development, doomed.

Crucially, the bourgeoisie’s conquest of political power wasn’t possible until capitalist economic relations had already, over centuries, spread across much of Europe. There had to be a material foundation for the capitalist class’s ultimate political victories: without economic power—the accumulation of material resources through institutions they controlled—capitalists could never have achieved political power. That is to say, much of the enormously protracted social revolution occurred before the final “seizure of the state.”

If historical materialism is right, as it surely is, the same paradigm must apply to the transition from capitalism to socialism. The working class can never complete its conquest of the state until it commands considerable economic power—not only the power to go on strike and shut down the economy but actual command over resources, resources sufficient to compete with the ruling class. The power to strike, while an important tool, is not enough. Nor are mere numbers, however many millions, enough, as history has shown. The working class needs its own institutional bases from which to wage a very prolonged struggle, and these institutions have to be directly involved in the production and accumulation of resources. Only after some such “alternative economy,” or socialized economy, has emerged throughout much of the world alongside the rotting capitalist economy will the popular classes be in a position to finally complete their takeover of states. For they will have the resources to politically defeat the—by then—weak, attenuated remnants of the capitalist class.

Marx, in short, was wrong to think there would be a radical disanalogy between the transition to capitalism and the transition to socialism. Doubtless the latter process (if it happens) will take far less time than the earlier did, and will be significantly different in many other respects. But social revolutions on the scale we’re discussing—between vastly different modes of production—are always very gradual, never a product of a single great moment (or several moments) of historical “rupture” but rather of many decades of continual ruptures.[3] Why? Simply because ruling classes are incredibly tenacious, they have incredible powers of repression, and it requires colossal material resources to defeat them—especially in the age of globalized capitalism.

Building a new mode of production

What we must do, then, is to laboriously construct new relations of production as the old capitalist relations fall victim to their contradictions. But how is this to be done? At this early date, it is, admittedly, hard to imagine how it can be accomplished. Famously, it’s easier to imagine the end of the world than the end of capitalism.

But two things are clear. First, a significant amount of grassroots initiative is necessary. The long transition will not take place only on one plane, the plane of the state; there will be a tumult of creative energy on sub-state levels, as there was during Europe’s transition into capitalism. (Of course, in the latter case it was typically to establish predatory and exploitative relations, not democratic or communal ones, but the point holds.) The many forms of such energy can hardly be anticipated, but they will certainly involve practices that have come to be called the “solidarity economy,” including the formation of cooperatives of all types, public banks, municipal enterprises, participatory budgeting, mutual aid networks, and so on. In a capitalist context it is inconceivable that states will respond to crisis by dramatically improving the circumstances of entire populations; as a result, large numbers of people will be compelled to build new institutions to survive and to share and accumulate resources. Again, this process, which will occur all over the world and to some degree will be organized and coordinated internationally, will play out over generations, not just two or three decades.

In the long run, moreover, this solidarity economy will not prove to be some sort of innocuous, apolitical, compatible-with-capitalism development; it will foster anti-capitalist ways of thinking and acting, anti-capitalist institutions, and anti-capitalist resistance. It will facilitate the accumulation of resources among organizations committed to cooperative, democratic, socialized production and distribution, a rebuilding of “the commons,” a democratization of the state. It will amount to an entire sphere of what has been called “dual power” opposed to a still-capitalist state, a working-class base of power to complement the power of workers and unions to strike.

The second point is that, contrary to anarchism, it will be necessary to use the state to help construct a new mode of production. Governments are instruments of massive social power and they cannot simply be ignored or overthrown in a general strike. However unpleasant or morally odious it may be to participate in hierarchical structures of political power, it has to be a part of any strategy to combat the ruling class.

Activists and organizations will pressure the state at all levels, from municipal to national, to increase funding for the solidarity economy. In fact, they already are, and have had success in many countries and municipalities, including in the U.S. The election of more socialists to office will encourage these trends and ensure greater successes. Pressure will also build to fund larger worker cooperatives, to convert corporations to worker-owned businesses, and to nationalize sectors of the economy. And sooner or later, many states will start to give in.

Why? One possible state response to crisis, after all, is fascism. And fascism of some form or other is indeed being pursued by many countries right now, from Brazil to Hungary to India to the U.S. But there’s a problem with fascism: by its murderous and ultra-nationalistic nature, it can be neither permanent nor continuously enforced worldwide. Even just in the United States, the governmental structure is too vast and federated, there are too many thousands of relatively independent political jurisdictions, for a fascist regime to be consolidated in every region of the country. Fascism is only a temporary and partial solution for the ruling class. It doesn’t last.

The other solution, which doubtless will always be accompanied by repression, is to grant concessions to the masses. Here, it’s necessary to observe that the state isn’t monolithically an instrument of capital. While capital dominates it, it is a terrain of struggle, “contestations,” “negotiations,” of different groups—classes, class subgroups, interest groups, even individual entities—advocating for their interests. Marxists from Engels, Kautsky, and Lenin to Miliband and Poulantzas to more recent writers have felled forests writing about the nature of the capitalist state, but for the purposes of revolutionary strategy all you need is some critical common sense (as Noam Chomsky, dismissive of self-indulgent “theorizing,” likes to point out). It is possible for popular movements to exert such pressure on the state that they slowly change its character, thereby helping to change the character of capitalist society.

In particular, popular organizations and activists can take advantage of splits within the ruling class to push agendas that benefit the populace. The political scientist Thomas Ferguson, among others, has shown how the New Deal, including the epoch-making Wagner Act and Social Security Act, was made possible by just such divisions in the ranks of business. On a grander scale, Western Europe’s long transition from feudalism to capitalism was accompanied by divisions within the ruling class, between more forward-thinking and more hidebound elements. (As is well known, a number of landed aristocrats and clergymen even supported the French Revolution, at least in its early phases.) Marx was therefore wrong to imply that it’s the working class vs. the capitalist class, monolithically. This totally Manichean thinking suggested that the only way to make a revolution is for the proletariat to overthrow the ruling class in one blow, so to speak, to smash a united reactionary opposition that, moreover, is in complete control of the state (so the state has to be seized all at once).

On the contrary, we can expect the past to repeat itself: as crises intensify and popular resistance escalates, liberal factions of the ruling class will split off from the more reactionary elements in order to grant concessions. In our epoch of growing social fragmentation, environmental crisis, and an increasingly dysfunctional nation-state, many of these concessions will have the character not of resurrecting the centralized welfare state but of encouraging phenomena that seem rather “interstitial” and less challenging to capitalist power than full-fledged social democracy is. But, however innocent it might seem to support new “decentralized” solutions to problems of unemployment, housing, consumption, and general economic dysfunction, in the long run, as I’ve said, these sorts of reforms will facilitate the rise of a more democratic and socialized political economy within the shell of the decadent capitalist one.

At the same time, to tackle the immense crises of ecological destruction and economic dysfunction, more dramatic and visible state interventions will be necessary. They may involve nationalizations of the fossil fuel industry, enforced changes to the polluting practices of many industries, partial reintroductions of social-democratic policies, pro-worker reforms of the sort that Bernie Sanders’ campaign categorized under “workplace democracy,” etc. Pure, unending repression will simply not be sustainable. These more “centralized,” “statist” reforms, just like the promotion of the solidarity economy, will in the long run only add to the momentum for continued change, because the political, economic, and ecological context will remain that of severe worldwide crisis.

Much of the ruling class will of course oppose and undermine progressive policies—especially of the more statist variety—every step of the way, thus deepening the crisis and doing its own part to accelerate the momentum for change. But by the time it becomes clear to even the liberal sectors of the business class that its reforms are undermining the long-term viability and hegemony of capitalism, it will be too late. They won’t be able to turn back the clock: there will be too many worker-owned businesses, too many public banks, too many state-subsidized networks of mutual aid, altogether too many reforms to the old type of neoliberal capitalism (reforms that will have been granted, as always, for the sake of maintaining social order). The slow-moving revolution will feed on itself and will prove unstoppable, however much the more reactionary states try to clamp down, murder dissidents, prohibit protests, and bust unions. Besides, as Marx predicted, the revolutionary project will be facilitated by the thinning of the ranks of the capitalist elite due to repeated economic collapses and the consequent destruction of wealth.

Just as the European absolutist state of the sixteenth to nineteenth centuries was compelled to empower—for the sake of accumulating wealth—the capitalist classes that created the conditions of its demise, so the late-capitalist state will be compelled, for the purposes of internal order, to acquiesce in the construction of non-capitalist institutions that correct some of the “market failures” of the capitalist mode of production. The capitalist state will, of necessity, be a participant in its own demise. Its highly reluctant sponsorship of new practices of production, distribution, and social life as a whole—many of them “interstitial” at first—will be undertaken on the belief that it’s the lesser of two evils, the greater evil being the complete dissolution of capitalist power resulting from the dissolution of society.

It is impossible to predict this long process in detail, or to say how and when the working class’s gradual takeover of the state (through socialist representatives and the construction of new institutions on local and eventually national levels) will be consummated. Nor can we predict what the nation-state itself will look like then, what political forms it will have, how many of its powers will have devolved to municipal and regional levels and how many will have been lost to supra-national bodies of world governance. Needless to say, it is also hopeless to speculate on the future of the market, or whether various kinds of economic planning will, after generations, mostly take the place of the market.

As for “the dictatorship of the proletariat,” this entity, like the previous “dictatorship of the bourgeoisie,” won’t exist until near the end of the long process of transformation. Marxists, victims of impatience as well as the statist precedents of twentieth-century “Communist” countries, have traditionally gotten the order wrong, forgetting the lesson of Marxism itself that the state is a function of existing social relations and can’t simply be taken over by workers in the context of a still-wholly-capitalist economy. Nor is it at all “dialectical” to think that a group of workers’ representatives can will a new economy into existence, overcoming the authoritarian, bureaucratic, inefficient, exploitative institutional legacies of capitalism by a few acts of statist will. Historical materialism makes clear the state isn’t so radically socially creative![4]

Instead, the contrast that will appear between the stagnant, “fettering” old forms of capitalism and the more rational and democratic forms of the emergent economy is what will guarantee, in the end, the victory of the latter.

An ecumenical activism

In a necessarily speculative and highly abstract way I’ve tried to sketch the logic of how a new economy might emerge from the wreckage of capitalism, and how activists with an eye toward the distant future might orient their thinking. It should be evident from what I’ve said that there isn’t only one way to make a revolution; rather, in a time of world-historic crisis, simply fighting to humanize society will generate anti-capitalist momentum. And there are many ways to make society more humane.

Consider the social democratic path, the path of electing socialists and pressuring government to expand “welfare state” measures. Far-leftists often deride this approach as merely reformist; in the U.S., it’s also common to dismiss the idea of electing progressive Democrats such as Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez because supposedly the Democratic Party is hopelessly capitalist and corrupt. It can’t be moved left, and it will certainly never be a socialist party.

According to Regeneration Magazine, for instance, a voice of the Marxist Center network, “Reformism accepts as a given the necessity of class collaboration, and attempts to spin class compromise as a necessary good. One of the more popular strategic proposals of the reformist camp is the promotion of candidates for elected office running in a capitalist party; a clear instance of encouraging class collaboration.”

There are a number of possible responses to such objections. One might observe that if the left insists on absolute purity and refuses to work with anyone who can be seen as somehow “compromised,” it’s doomed to irrelevance—or, worse, it ends up fracturing the forces of opposition and thus benefits the reactionaries. It is a commonplace of historiography on fascism that the refusal of Communist parties in the early 1930s to cooperate with socialists and social democrats only empowered the Nazis and other such elements—which is why the Stalinist line changed in 1934, when the period of the Popular Front began. Then, in the U.S., began Communist efforts to build the Democrat-supported CIO (among other instances of “collaboration” with Democrats), which was highly beneficial to the working class. Leftists, more than anyone else, should be willing and able to learn from history.

Or one might state the truism that social democracy helps people, and so if you care about helping people, you shouldn’t be opposed to social democracy. It may be true that the Democratic Party is irredeemably corrupt and capitalist, but the more left-wing policymakers we have, the better. Democrats have moved to the left in the past, e.g. during the New Deal and the Great Society, and they may be able to move (somewhat) to the left in the future. One of the goals of socialists should be to fracture the ruling class, to provoke splits that provide opportunities for socialist organizing and policymaking.

At the same time, the strategy of electing left-wing Democrats or “reformists” should, of course, be complemented by an effort to build a working-class party, not only for the sake of having such a party but also to put pressure on the mainstream “left.” Anyway, the broader point is just that the state is an essential terrain of struggle, and all means of getting leftists elected have to be pursued.

Personally, I’m skeptical that full-fledged social democracy, including an expansion of it compared to its traditional form, is possible any longer, least of all on an international or global scale. Thus, I don’t have much hope for a realization of the Jacobin vision, that societies can pass straight into socialism by resurrecting and continuously broadening and deepening social democracy (on the basis of popular mobilization to combat capitalist reaction). Surely Marxism teaches us that we can’t resuscitate previous social formations after they have passed from the scene, particularly not institutional forms that have succumbed (or are in the process of succumbing) to the atomizing, disintegrating logic of capital. The expansive welfare state was appropriate to an age of industrial unionism and limited mobility of capital. Given the monumental crises that will afflict civilization in the near future, the social stability and coherence required to sustain genuine social democracy will not exist.

But that doesn’t mean limited social-democratic victories aren’t still possible. They surely are. And in the long run, they may facilitate the emergence of new democratic, cooperative, ecologically viable modes of production, insofar as they empower the left. Even something like a Green New Deal, or at least a partial realization of it, isn’t out of the question.

On the other hand, while mass politics is necessary, that doesn’t mean we should completely reject non-electoral “movementism.” As I’ve argued, the project of building a new society doesn’t happen only on the level of the state; it also involves other types of popular organizing and mobilizing, including in the solidarity economy. The latter will likely, indeed, be a necessity for people’s survival in the coming era of state incapacity to deal with catastrophe.

Not all types of anarchist activism are fruitful or even truly leftist, but the anarchist intuition to organize at the grassroots and create horizontal networks of popular power is sound. Even in the ultra-left contempt for reformism there is the sound intuition that reforms are not enough, and we must always press forward towards greater radicalism and revolution.

Ecological apocalypse?

An obvious objection to the conception and timeframe of revolution I’ve proposed is that it disregards the distinct possibility that civilization will have disappeared a hundred years from now if we don’t take decisive action immediately. For one thing, nuclear war remains a dire threat. But even more ominously, capitalism is turbocharged to destroy the natural bases of human life.

There’s no need to run through the litany of crimes capitalism is committing against nature. Humanity is obviously teetering on the edge of a precipice, peering down into a black hole below. Our most urgent task is to, at the very least, take a few steps back from the precipice.

The unfortunate fact, however, is that global capitalism will not be overcome within the next few decades. It isn’t “defeatist” to say this; it’s realistic. The inveterate over-optimism of many leftists, even in the face of a dismal history, is quite remarkable. Transitions between modes of production aren’t accomplished in a couple of decades: they take generations, and involve many setbacks, then further victories, then more defeats, etc. The long march of reactionaries to their current power in the U.S. took fifty years, and they existed in a sympathetic political economy and had enormous resources. It’s hard to believe socialists will be able to revolutionize the West and even the entire world in less time.

Fortunately, it is possible to combat ecological collapse even in the framework of capitalism, for example by accelerating the rollout of renewable energy. It is far from hopeless, also, to try to force governments to impose burdensome regulations and taxes on polluting industries, or even, ideally, to shut down the fossil fuel industry altogether. Capitalism itself is indeed, ultimately, the culprit, but reforms can have a major effect, at the very least buying us some time.

Climate change and other environmental disasters may, nevertheless, prove to be the undoing of civilization, in which case the social logic of a post-capitalist revolution that I’ve outlined here won’t have time to unfold. Nothing certain can be said at this point—except that the left has to stop squabbling and get its act together. And it has to be prepared for things to get worse before they get better. As Marx understood, that’s how systemic change tends to work: the worse things get—the more unstable the system becomes—the more people organize to demand change, and in the end the likelier it is that such change will happen.

The old apothegm “socialism or barbarism” has to be updated: it’s now socialism or apocalypse.

But the strategic lesson of the “purifications” I’ve suggested of Marxist theory remains: the path to socialism is not doctrinaire, not sectarian, not wedded to a single narrow ideological strain; it is catholic, inclusive, open-ended—both “reformist” and non-reformist, statist and non-statist, Marxist and anarchist, Democrat-cooperating and -non-cooperating. Loath as we might be to admit it, it is even important that we support lesser-evil voting, for instance electing Biden rather than Trump. Not only does it change people’s lives to have a centrist instead of a fascist in power; it also gives the left more room to operate, to influence policy, to advocate “radical reforms” that help lay the groundwork for new economic relations.

It’s time for creative and flexible thinking. The urgency of our situation demands it.

[1] Being an outgrowth of my Master’s thesis, the book over-emphasizes worker cooperatives. It does, however, answer the usual Marxist objections to cooperatives as a component of social revolution.

[2] The state’s official censorship may have required Marx to censor himself in the Preface, but I know of nowhere else that he expresses his theory in causal, as opposed to functionalist, terms. That is, he doesn’t provide a mechanism by which fettering leads to successful revolution. My restatement of his conception in terms of relative fettering—relative to an emergent mode of production—is an attempt to provide such a mechanism.

[3] If someone will counterpose here the example of Russia, which didn’t require “many decades” to go from capitalism and late-feudalism to a “Stalinist mode of production,” I’d reply that the latter was in fact like a kind of state capitalism (as Richard Wolff, for example, has argued), and therefore wasn’t so very different in relevant respects from the authoritarian, exploitative, surplus-extracting, capital-accumulating economy that dominated in the West.

[4] This is why I claim in the above-linked book that my “revisions” of Marxism are really purifications of it, eliminations of mistakes that finally make the properly understood Marxist conception of revolution consistent with the premises of historical materialism.

On 1 May 2020, which was International Worker’s Day, 18 Indian migrant workers boarded and hid in a cement mixer which was carrying them from Mumbai to Uttar Pradesh. In the nationwide lockdown imposed by the Indian government, migrant workers have found themselves to be forsaken by the capitalist ventures which employ them for minimal wages and by the government which has not done enough to ensure their safety in the time of Coronavirus.

On 1 May 2020, which was International Worker’s Day, 18 Indian migrant workers boarded and hid in a cement mixer which was carrying them from Mumbai to Uttar Pradesh. In the nationwide lockdown imposed by the Indian government, migrant workers have found themselves to be forsaken by the capitalist ventures which employ them for minimal wages and by the government which has not done enough to ensure their safety in the time of Coronavirus.

Planet of the Humans, the new documentary from Michael Moore and Jeff Gibbs, seeks to expose the false promises of renewable energy. It also warns against the bad leadership on climate issues from liberal environmental groups like the Sierra Club and Bill McKibben at 350.org.

Planet of the Humans, the new documentary from Michael Moore and Jeff Gibbs, seeks to expose the false promises of renewable energy. It also warns against the bad leadership on climate issues from liberal environmental groups like the Sierra Club and Bill McKibben at 350.org.

This is the transcript of a talk originally given on April 4, 2020 as part of an online meeting titled “

This is the transcript of a talk originally given on April 4, 2020 as part of an online meeting titled “

This article was written for L’Anticapitaliste, the weekly newspaper of the New Anticapitalist Party (NPA) of France.

This article was written for L’Anticapitaliste, the weekly newspaper of the New Anticapitalist Party (NPA) of France.

Our article, “

Our article, “

The Bernie Sanders campaign is over – now what? For a socialist left that has largely orbited Sanders since 2015, figuring out life without a rallying figure might be harder than we think. In their piece, “

The Bernie Sanders campaign is over – now what? For a socialist left that has largely orbited Sanders since 2015, figuring out life without a rallying figure might be harder than we think. In their piece, “

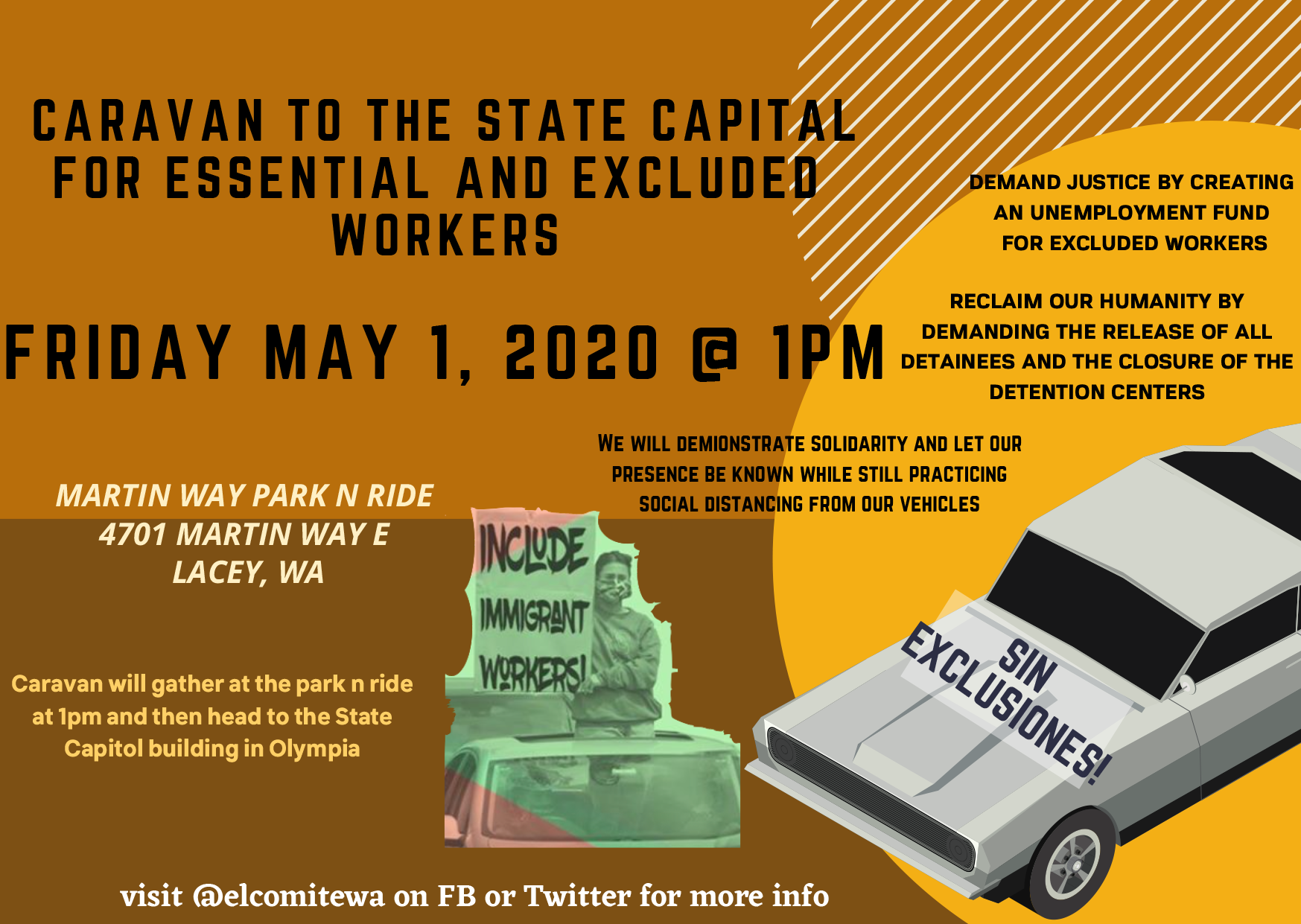

For May Day, 2020, three car caravans converged at Washington’s State Capitol, yesterday, Friday, in our car caravan for Excluded and Essential workers. Our demands included full benefits, health care, unemployment benefits and the $1200 stimulus payment for all, no matter what a person’s immigrant status, to be paid for by the State of Washington if not paid for by the Federal Government. We also demanded the closing of the Northwest Detention Center in Tacoma (NWDC) so crossing the border seeking work wouldn’t be a possible death sentence from Covid-19.

For May Day, 2020, three car caravans converged at Washington’s State Capitol, yesterday, Friday, in our car caravan for Excluded and Essential workers. Our demands included full benefits, health care, unemployment benefits and the $1200 stimulus payment for all, no matter what a person’s immigrant status, to be paid for by the State of Washington if not paid for by the Federal Government. We also demanded the closing of the Northwest Detention Center in Tacoma (NWDC) so crossing the border seeking work wouldn’t be a possible death sentence from Covid-19.

On April 8, Bernie Sanders ended his presidential campaign, but said that the movement around him must continue. Then on April 13, he went “all in” for Joe Biden, endorsing Biden’s candidacy and setting up joint policy committees linking the two campaign staffs. Many who had been activated by Sanders’s campaign, including many young people and others who had never been engaged in politics before, are disappointed. But being discouraged doesn’t provide a political direction. What is the balance sheet of the campaign and what conclusions can we begin to draw?

On April 8, Bernie Sanders ended his presidential campaign, but said that the movement around him must continue. Then on April 13, he went “all in” for Joe Biden, endorsing Biden’s candidacy and setting up joint policy committees linking the two campaign staffs. Many who had been activated by Sanders’s campaign, including many young people and others who had never been engaged in politics before, are disappointed. But being discouraged doesn’t provide a political direction. What is the balance sheet of the campaign and what conclusions can we begin to draw?

As of May 4, Puerto Rico is reporting 1,806 confirmed coronavirus infections and 97 Covid-19 deaths. Compounding the public health crisis, recent natural disasters (hurricanes and earthquakes) and long-term neoliberal austerity have

As of May 4, Puerto Rico is reporting 1,806 confirmed coronavirus infections and 97 Covid-19 deaths. Compounding the public health crisis, recent natural disasters (hurricanes and earthquakes) and long-term neoliberal austerity have

In the age of COVID-19, it’s even more obvious than it’s been for at least a couple of decades that capitalism is entering a long, drawn-out period of unprecedented global crisis. The Great Depression and World War II will likely, in retrospect, seem rather minor—and temporally condensed—compared to the many decades of ecological, economic, social, and political crises humanity is embarking on now. In fact, it’s probable that we’re in the early stages of the protracted collapse of a civilization, which is to say of a particular set of economic relations underpinning certain social, political, and cultural relations. One can predict that the mass popular resistance, worldwide, engendered by cascading crises will gradually transform a decrepit ancien régime, although in what direction it is too early to tell. But left-wing resistance is already spreading and even gaining the glimmers of momentum in certain regions of the world, including—despite the ending of Bernie Sanders’ presidential campaign—the reactionary United States. Over decades, the international left will grow in strength, even as the right, in all likelihood, does as well.

In the age of COVID-19, it’s even more obvious than it’s been for at least a couple of decades that capitalism is entering a long, drawn-out period of unprecedented global crisis. The Great Depression and World War II will likely, in retrospect, seem rather minor—and temporally condensed—compared to the many decades of ecological, economic, social, and political crises humanity is embarking on now. In fact, it’s probable that we’re in the early stages of the protracted collapse of a civilization, which is to say of a particular set of economic relations underpinning certain social, political, and cultural relations. One can predict that the mass popular resistance, worldwide, engendered by cascading crises will gradually transform a decrepit ancien régime, although in what direction it is too early to tell. But left-wing resistance is already spreading and even gaining the glimmers of momentum in certain regions of the world, including—despite the ending of Bernie Sanders’ presidential campaign—the reactionary United States. Over decades, the international left will grow in strength, even as the right, in all likelihood, does as well.

This article was written for L’Anticapitaliste, the weekly newspaper of the New Anticapitalist Party (NPA) of France.

This article was written for L’Anticapitaliste, the weekly newspaper of the New Anticapitalist Party (NPA) of France.

As immigrant workers face increasingly harsh and dangerous pandemic conditions, activists staged a car protest at Vermont’s Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) data center. Draped with signs reading “Free All Detainees Now,” “Close this ICE Data Center,” and “Abolish ICE,” cars formed a half-mile honking loop in front of the center. The data center and other Homeland Security operations housed here, brought to the state by Senator Patrick Leahy (D), serves as a

As immigrant workers face increasingly harsh and dangerous pandemic conditions, activists staged a car protest at Vermont’s Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) data center. Draped with signs reading “Free All Detainees Now,” “Close this ICE Data Center,” and “Abolish ICE,” cars formed a half-mile honking loop in front of the center. The data center and other Homeland Security operations housed here, brought to the state by Senator Patrick Leahy (D), serves as a

Peter Dreier’s

Peter Dreier’s