Men in the (Indian) Sun

On 1 May 2020, which was International Worker’s Day, 18 Indian migrant workers boarded and hid in a cement mixer which was carrying them from Mumbai to Uttar Pradesh. In the nationwide lockdown imposed by the Indian government, migrant workers have found themselves to be forsaken by the capitalist ventures which employ them for minimal wages and by the government which has not done enough to ensure their safety in the time of Coronavirus.

On 1 May 2020, which was International Worker’s Day, 18 Indian migrant workers boarded and hid in a cement mixer which was carrying them from Mumbai to Uttar Pradesh. In the nationwide lockdown imposed by the Indian government, migrant workers have found themselves to be forsaken by the capitalist ventures which employ them for minimal wages and by the government which has not done enough to ensure their safety in the time of Coronavirus.

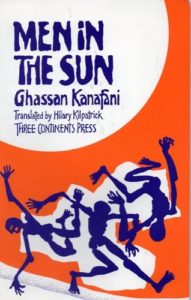

This scene of migrant workers traveling in a cement mixer is reminiscent of the renowned Palestinian writer Ghassan Kanafani’s short story Men in the Sun (1963). Three Palestinian refugees were trying to escape from Iraq to Kuwait without the requisite paperwork and found themselves stranded. Their desperate search for livelihood makes them agree to hide in a water tanker in order to cross a border unnoticed. The background of the story, although not mentioned, is the dispossession of Palestinians at the hands of Israeli settlers which created the event that is now commemorated as the ‘Nakba’ or the ‘Great Catastrophe’ of 1948.

The three Palestinians collaborate with a Palestinian driver who tells them they will have to hide in a water tanker in order to escape surveillance at a checkpoint. Their driver gets delayed at the checkpoint because of bureaucratic and administrative hurdles, only to discover that the three men have suffocated to death in the water tanker. The driver cries and asks “Why didn’t you knock on the sides of the tank”, forgetting that these men had no agency. Their lives had little value while they were alive, and no value once they were dead as their driver dumped their bodies on garbage heap in the desert.

Both, the migrant workers in India and Kanafani’s Palestinian refugees, had been rendered superfluous by states which should have been protecting them. Superfluous means excessive but also unnecessary—while the underpaid, migrant labour is essential in a developing, capitalist economy like India, the Indian government has shown that their lives mean little. In three weeks of the nation-wide lockdown, no measures were made for the rehabilitation or safe transport migrant labourers who form the backbone of the Indian economy. They are the first to be considered as expendable, while the bourgeois and elite sit in the safe comfort of their homes.

The act of hiding in a cement mixer or a water tanker shows us that we are often made to deliberately hide certain people from plain sight. The Indian state in the case of the Indian migrant labourers and the Israeli state in the case of Palestinian refugees has deliberately made certain people invisible to ensure the state’s smooth functioning. The American Jewish philosopher Hannah Arendt reflected on refugees and the problem of their assimilation within society. She notes that refugees were expected to lose any previous identity and assimilate in the nation which gave them refuge. Their own community, however, often berated them for giving up their religious or other identity and assimilating too quickly.

Refugees and migrants are expected to invisibly mix within their host society. As soon as the national lockdown was declared, no governmental thought or deliberation was given to the plight of migrant labourers: could they live somewhere they could follow social distancing, what could they eat in the absence of daily wages, could they return home in the absence of buses and trains? The ignorance of these problems shows that these people had long become superfluous and it only took a lockdown to reveal their status in society.

In The Human Condition (1958), Hannah Arendt theorises that it is our ability to labour, work and act that makes us human. While labour corresponds to daily needs and sustenance, work refers to fabrication at the hands of the human and the creation of atemporal objects at the hands of a temporal being. To act (and speak) refers to the human’s ability to create a shared public realm where a person’s unique identity is revealed. To become superfluous means to be robbed of the human condition, as the Indian migrant labourers have. They have been dehumanised by structures that profit from their existence, and have now relinquished them at their time of need.

By no longer viewing migrants and refugees as human, the state and capitalist structures which employ them absolve themselves of any responsibility towards them. The process of dehumanisation starts by creating superfluous beings who seem beyond the pale of pity and empathy. It stops seeming bizarre that people would resort to traveling in cement mixers or water tankers to reach destinations undetected. Their dehumanisation performs a perverse catharsis: there is no purge of emotions as the state has set a precedent of not viewing the labourers or refugees as humans who deserve our empathy. The final achievement of the project of dehumanisation is the creation of the apathetic viewer: one who cannot see and therefore cannot empathise with men in the harsh, Indian sun.