The American Working Class on Unfamiliar and Dangerous Terrain: A Fightback Begins

This article is being published simultaneously in the Australian journal Marxist Left Review (MLR) and in the U.S. journal New Politics. The article is related to a talk that the author gave to the Socialist Alternative of Australia that publishes MLR.

This article is being published simultaneously in the Australian journal Marxist Left Review (MLR) and in the U.S. journal New Politics. The article is related to a talk that the author gave to the Socialist Alternative of Australia that publishes MLR.

The working class in the United States faces tremendous difficulties, but there are some hopeful signs of movement in workplaces and unions, in communities, and on the left. As this article was being edited, the national uprising against the police murder of George Floyd spread across the country, complicating in ways that remain uncertain both the coronavirus and the planned reopening of the country intended to end the depression. Clearly, however, all of these events taken together suggest that we are entering a new era in the struggle for democracy and socialism.

WALNUT CREEK, CA – MARCH 23: Nurses line up to protest outside the Kaiser Permanente Walnut Creek Medical Center in Walnut Creek, Calif., on Sunday, March 22, 2020. California Nurses Association held a rally today to protest the lack of coronavirus supplies at the hospital. (Jose Carlos Fajardo/Bay Area News Group)

The American working class today faces three enormous problems. First, the coronavirus that continues to spread across the United States bringing suffering and death. We have now had 104,000 deaths. We may see soon a second wave of the pandemic as a result of a hasty reopening of the American economy without proper attention to protecting the health of working people and the society in general.

Second, we find ourselves in an economic crisis of unprecedented proportions, a second Great Depression that may be worse than the first. We have 43 million unemployed, a rate of about of 25 percent. A recent study estimates that 42 percent of these layoffs may become permanent; that is, at the other end of this slump we may still have an unemployment rate of 15 percent!

Third, under President Donald Trump, we have a new kind of government in the United States, an authoritarian government, hostile to unions, workers, people of colour, women and LGBT people, that is violating many of the norms and customs of all previous administrations and has created what we might now call a permanent constitutional crisis. Trump not only conquered and disciplined the Republican Party, he has also maintained his hard core following of about 40 percent of the electorate, and mobilised far right movements that include neo-Nazis and armed militias.

The working class before the current crisis

To understand how the situation of the US working class we have to ask a number of questions. What is the starting point? That is, what was the situation of US workers before the pandemic? What is the situation at present? And what sort of worker resistance is taking place now?

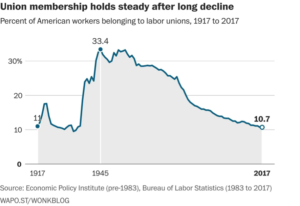

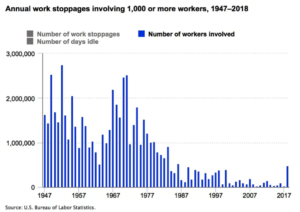

The US working class has been in decline since about 1980; that is, for 40 years, two generations, unions shrunk in size and social weight, strikes virtually disappeared, and labour’s voice in the country’s social and political life became weaker. Before the pandemic only 10 percent of all workers in America belonged to unions, and only 6 percent in the private sector. Few union members attended union meetings and many did not vote in union elections for their officers. During those 40 years wages stagnated, and in many workplaces conditions worsened and benefits declined.

In February 2018 a teachers’ strike in West Virginia led to a series of education workers’ strikes that lasted through 2019 in Oklahoma, Arizona, Kentucky, North Carolina, Colorado, Los Angeles and Oakland, California. In Chicago there was a 15-day strike by the Chicago Teachers Union and there was also a nine-day strike by the United Teachers of Los Angeles, both locals where more militant, rank-and-file caucuses had taken leadership of the union. The strikes involved about 500,000 teachers and other workers and in many cases won substantial gains. Yet the strikes did not spread to other public employees and seemed to have no impact on private sector workers.

There have also been dozens of strikes by nurses and other healthcare workers, some working for public, some for non-profit, and some for private hospitals. These strikes led by a variety of unions involved tens of thousands of workers, and all occurred before the current coronavirus pandemic.

There were several private sector strikes of note too in this same period of a few years before the coronavirus crisis. The Communications Workers of America led several of these strikes or followed its members when they led. On 13 April 2016 the Communication Workers of America (CWA) led a strike of 39,000 Verizon workers and after 45 days “they beat back company demands for concessions on job security and flexibility, won 1,300 additional union jobs, and achieved a first contract at seven Verizon Wireless stores.” The CWA also struck AT&T in 2016, Pacific Bell in 2017, and in 2018 9,500 CWA workers walked out at AT&T Midwest in a wildcat strike.

Service workers’ strikes grew in 2017-2019 as well. Seven UNITE HERE locals spread across seven time zones from Hawaii, San Francisco, Oakland, San Diego, San Jose, Detroit, to Boston, raising the slogan “One Job Should Be Enough”, and struck Marriott (Marriott, Westin and Sheraton) Hotels for two months in 2018. They won higher wages, improved benefits, and greater job security.

The Stop & Shop strike should also be mentioned. Thirty-five thousand members of five United Food and Commercial Workers locals in the states of Massachusetts, Rhode Island, and Connecticut walked out on April 11 for better pay and to defend their healthcare plans. The strike, whose picket lines were honoured by the Teamsters, proved very effective, and the union demonstrated that it could successfully defend its members.

The United Auto Workers strike against General Motors in 2019 involved 48,000 workers at 50 plants across the United States and lasted from September 15 to October 16, but it failed to achieve what many workers thought should be its chief goal, the elimination of the many tiers – different pay rates – among GM workers. While each of these was a significant strike – one a success and the other not – they had little impact on the labour movement as a whole.

Taken together, all of the private sector strikes mentioned here demonstrated that labour unions were overcoming the myth of the 1980s to the 2000s that the strike was dead. The strike still lives.

Labour union activists often talk about the “labour movement”, but in reality, it is a misnomer. There are many labour union organisations, but for decades there has not been much movement. Why is that? During the entire post-war period, but particularly after the mid-1970s, American union leaders largely gave up the struggle against employers, against the capitalist class. Even before that, beginning in the late 1930s, the labour bureaucracy became a social caste in the working class, no longer working in the industry they came from, earning higher salaries, enjoying special health and retirement programs and perquisites such as cars and expense accounts, and often spending their working time with company and government officials. The union officials believed that their location in industrial relations and in society gave them a privileged position and that they better understood the choices facing the union than its members did.

The officials by and large adopted a philosophy of “partnership” with employers, working to protect the employers from government supervision or foreign competition, believing that the profitability of the corporations insured their members’ jobs and wages. Anxious to avoid confrontation to defend their members and enhance their situation, they turned to the Democratic Party to pass “labour law reform” that would make labour organising easier, though one Democratic Party president after another let them down year after year. All of this contributed to the decline in membership, the disappearance of the strike, and the stagnation of wages.

Other worker movements

While the labour unions – with the exception of the recent teacher strikes – have mostly been quiet for the last few decades, there have been other workers’ movements. The most important of these are the immigrant movement of 2006, the Occupy Wall Street Movement of 2011, and the Black Lives Matter movement in 2014.

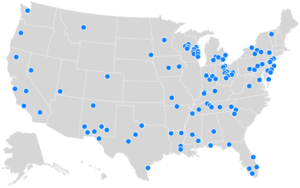

Map above: Immigrant demonstrations at the peak in May 2006.

While the AFL-CIO and some unions offered token support for these movements, in truth organised labour failed to fully embrace them. The labour bureaucracy does not form alliances with such movements when they come along, it does not mobilise its members to support these movements, nor does it use its economic power – the power of the strike – to defend immigrants and Black workers when they face racist policies. When social movements occur, generally they do so on their own, and labour goes its own way. The two seldom converge except where rank-and-file workers or some local union officer decide to take up the movement issues – and that is rare.

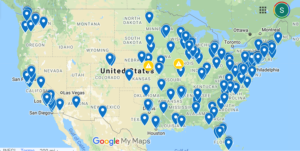

Map above: Occupy Wall Street occupations and demonstrations in US in 2011.

The social movements, which are clearly workers’ movements, tend to be episodic. They sometimes arise in reaction to positive proposals from the government, as happened with the immigrant movement of 2006, which responded to Republican President George W. Bush’s proposal for immigration reform. Or more typically they respond to an adverse development, as Occupy Wall Street did to the 2008 recession and Black Lives Matter reacted to police racism and violence. In any case, these movements of working people tend not to form permanent organisations. A wide variety of immigrant groups, from the Washington, D.C.-based National Council of La Raza to local hometown clubs and soccer teams, created the immigrant reform movement, but never coalesced into a new national organisation.

Map above: Created by students, showing Black Lives Matter protests in 2014-15.

Occupy Wall Street drew in many individuals concerned about the issues of economic inequality and the role of money in politics, but when Barack Obama’s White House organised suppression through coordination with local police forces, with 8,000 arrests, it never recovered. Black Lives Matter never called a national convention to create a new group, and afterwards the philanthropic foundations, NGOs and the Democratic Party swooped down on it and drew off a number of its leaders. It ceased to be a movement, though some local protesters adopted its name and continue to do so. The Me Too movement against men’s sexual assaults on women began with wealthy and powerful women in high places, such as actors, but it also had a powerful influence among women in all social classes including the working class; however no new women’s organisation and movement arose.

The Bernie Sanders campaigns of 2016 and 2020

Bernie Sanders’ two campaigns for president clearly captured the energy of the Occupy Wall Street movement and adopted two of its principal ideas: America’s growing economic inequality and the inordinate role of money in politics. Sanders developed an economic program that spoke to the issues facing millions of Americans, with the emphasis on health insurance for all (Medicare for all), free higher education, higher wages of at least $15.00 per hour. He also called for labour union reforms that he argued would double the size and strength of labour. Sanders has had a reputation for years of supporting unions and their strikes, something he continued during his campaigns.

In 2016, most US labour organisations followed the historic pattern and endorsed Sanders’ opponent Hillary Clinton, the candidate of the Democratic Party establishment and of a very large section of the American bourgeoisie. Very few national labour unions endorsed Sanders in 2016 and/or in 2020. The Communications Workers of America (CWA), National Nurses United (NNU), the American Postal Workers Union (APWU), United Electrical Workers Union (UE) and the National Union of Healthcare Workers (NUHW) did endorse Sanders, and so too did dozens of state, regional, and local unions, and many, many individual union members supported him.

In 2020, with 29 Democratic Party candidates in the race at first, most unions delayed making endorsements, in part because they feared problems with their many members who personally supported Sanders in 2016. The presence in the primary of the progressive Elizabeth Warren in 2020 also complicated the situation and led some unions to hesitate. None of the candidates got very many union endorsements in 2020 until Joe Biden had won the South Carolina primary and the endorsement of his most significant opponents. Then in the midst of the coronavirus pandemic Sanders dropped out of the race and also endorsed Biden. Biden and Sanders then formed an alliance to work on policy issues, moving Biden a little to the left at least on paper, which made it clear that virtually all labour unions would endorse Biden for president.

There is no doubt that Bernie Sanders’ two campaigns had an enormous impact on popular consciousness and the working class. His campaign platform and his speeches popularised and legitimated the rights of labour unions and workers and working-class demands for a better work life and a better life in their communities. Sanders may indirectly have helped to inspire the teachers who went on strike in 2017, mostly in “red states” dominated by the Republican Party. Yet in the last five years of Sanders’ campaigns, apart from the teachers, we saw no significant uptick in union organising or strikes. Sanders changed consciousness, but, at least so far, that has not resulted in significant union action.

There appears to be an interest in independent political alternatives to the left of the Democratic Party among some Sanders followers. In Los Angeles in 2020, after his withdrawal, Sanders’ campaign organisation, Our Revolution, voted to leave the Democratic Party and explore an alliance with the People’s Party Movement; but it is small, not a political party, and is running no candidates in 2020, so it is not a genuine option.

There is no significant alternative to the left of the Democratic Party that can provide an option for the working class. The Green Party, which has never won more than 2.2 percent of the total vote for president, won only 1 percent in the last couple of elections. Its importance is that it has a national presence on state ballots. In New York State Howie Hawkins, a retired truck driver, an open socialist, and the 2020 presidential candidate, has been an indefatigable campaigner and won enough votes in his last race for governor (50,000) to keep the Green Party on the state ballot, but elsewhere the party is not very significant.

The effect of the coronavirus crisis on workers

American workers have been affected by the coronavirus in quite different ways. It is estimated that about 29 percent of all American workers have been able to work from home; this includes many technical employees, engineers, architects, professors and teachers and other white-collar professions. About 40 million workers, or 25 percent of the American workforce, has been laid off. Still, millions of essential workers continue to perform their duties, often risking exposure to coronavirus from co-workers, the public, or passengers on public transportation.

Economic and racial inequality is also quite evident. A higher proportion of Blacks and Latinos have become sick and died. In Chicago Black people make 32 percent of the population, but they make up 72 percent of the coronavirus deaths. In New York both Blacks and Latinos are dying at twice the rate of whites. This is largely due to underlying conditions – high blood pressure, diabetes and respiratory disease – but also to working in essential jobs, as well as lack of healthcare and overcrowded housing.

Racism appears everywhere in this crisis. Asian Americans have experienced verbal abuse and violent attacks as the bearers of what Trump called the “Chinese virus”. Trump closed the border to asylum seekers and has now ordered that for 60 days the government will issue no green cards, which grant immigrants permanent residency and the right to work in the United States.

While men die at higher rates, the pandemic also disproportionately affects women. Many are homecare workers, nursing home workers and other low-wage caregivers with less protection. Women make up 87 percent of registered nurses and 71 percent of cashiers. There is also concern that under stay-at-home orders women are experiencing more domestic violence. At the same time, conservative officials in Ohio, Mississippi and Texas have declared abortions to be “non-essential” and have suspended the procedure during the coronavirus pandemic. The courts have overruled some of those orders.

Workers take action

Throughout the pandemic, federal and state governments and public and private employers failed to protect workers’ health and their income. Essential workers who were forced to continue working without adequate safety and health protection either protested or walked off the job in hundreds of mostly small, brief, and localised wildcat strikes. Some of these, like a small walkout at an Amazon warehouse in New York, garnered publicity but failed to find a mass following. Others had a bigger impact.

Nurses and other hospital workers organised demonstrations to demand masks, gowns, and ventilators. Many nurses protested at their hospitals, but some from the National Nurses United went to the White House to demand that Trump invoke the Defense Production Act (DPA) to order the production of masks, ventilators and coronavirus test kits. While there, in a moving tribute, they read the names of their co-workers killed by the virus. Federal and state governments and hospital managers responded by making greater efforts to provide supplies for workers.

Nurses were not alone. In mid-March, led by the Movement of Rank and File Educators (MORE) teachers threatened a sickout to force the closure of the New York public schools when Mayor de Blasio and their own union, the United Federation of Teachers, failed to do so. In late April about 50 workers walked off the job at the Smithfield meatpacking plant in Nebraska over health and safety issues. The governor promised to bring testing and contact tracing to the plant. In Washington, where there is a long history of worker strikes, hundreds of fruit packers struck for safer working conditions and hazardous duty pay.

The protests are myriad: Truck drivers who own their own trucks have organised protests over their falling rates in several states, and Uber drivers in San Francisco organised a protest at a stockholder meeting against their attempt to repeal a law that protects Uber workers’ rights. Fast food workers in several states have walked off the job, some in strikes coordinated by the “Fight for $15” movement. Retail workers walked off their jobs at the American Apparel clothing plant in Selma, Alabama. The protests, while plentiful and diverse, still remain mostly small and brief and most have not had a significant impact on management, though some have won improvements in health protection or higher wages.

Payday Report “Strike Map” claims some 250 wildcat strikes in May 2020, but the claim is somewhat misleading since many of the actual events were not strikes at all but simply protests.

Some unions have provided leadership. The Amalgamated Transit Union has supported bus drivers who have struck over health concerns in Detroit, Birmingham, Richmond, and Greensboro. The Carpenters Union, which represents about 10,000 workers in Massachusetts, ordered its members to strike on April 5 over concerns about COVID-19 and did not end the strike until April 20. Many unions issued statements calling for employers and government to protect their members and provided helpful information. And unions have also lobbied Congress.

With the exception of the nurses’ unions, by and large most labour unions have provided little more leadership than government or business in this hybrid health and economic crisis. Many unions issued statements calling for employers and government to protect their members and provided helpful information. And unions have also lobbied Congress. But in general union leaders have not attempted to raise the level of class struggle to the extent that might be possible.

Some important unions capitulated to reopening factories and resuming production, even though it is clear that it may put their members’ health at risk. As early as May 5 the United Auto Workers conceded that the company had the contractual authority to resume production in May in the GM, Ford, and Fiat-Chrysler plants, without strong guarantees of health protections. Ford, after reopening, shut down two plants, one in Chicago and another in Dearborn, Michigan because of new COVID-19 cases.

Fearing the coronavirus, demobilised by the shutdown, then recalled to work without adequate protections, the crisis has further divided and demoralised much of the working class. As we write at the end of May, there has been no mass mobilisation of workers on an industrial, regional, or national scale. Though some in the left have that in mind.

The left organises

Labour Notes, the newspaper, website, and educational centre, represents the most important institution of the labour left in the United States. Its biannual conferences generally bring together a few thousand union activists, while hundreds attend its travelling schools held in different cities around the country. Its books provide useful tools for organisers and it has helped to bring together workers in the same industry so that they can build movements to revitalise their unions. Labour Notes, for example, helped to create the United Caucuses of Rank-and-File Educators (UCORE), a network of caucuses in the teachers unions – in Chicago, Los Angeles, Philadelphia, New York and Massachusetts, and other cities and states – is now also building a similar network for those in higher education.

The largest left organisation in the United States, the Democratic Socialists of America (DSA) – with some 60,000 members in every state, in all major cities and many towns and rural areas – had been active before the current crisis among nurses and teachers. DSA has undertaken some new initiatives. It has joined forces with the small United Electrical Workers Union known as the UE, which organises in a variety of industries, and together they have created the Emergency Workplace Organizing Committee (EWOC). EWOC, adopting the “distributed organising” techniques of the Sanders campaign, is now training hundreds of volunteer organisers to help shop-floor activist organisers in their workplaces. DSA has also begun to organise a network of restaurant workers in several cities and towns. These new DSA initiatives raise the possibility of organising thousands of workers and helping them to take action, with or without a union, to solve their immediate problems. It also may make possible the recruitment of large numbers of workers to DSA.

And mutual aid?

Some on the left, especially the anarchist and anti-capitalist left, have also been engaged in organising what is called “mutual aid”, though their projects are few in number and small. While leftists sometimes talk about mutual aid as leading to “dual power” – a period in a revolutionary situation where there are two rival governments – there is no evidence of such projects representing any significant working class movement or any alternative to government on any level, admirable as the attempt to build solidarity may be. Far more important than left-led groups in that work are the thousands of mutual assistance projects across the country that have sprung up from block clubs and neighbourhood associations in local communities that involve bringing food to the hungry, checking in on the elderly and handicapped, providing health education, sharing books and educational materials, and myriad other good works. Those largely traditional community groups, however, seldom have a political dimension.

Latino immigrant communities, organising through their neighbourhood groups, workers’ centres and other advocacy organisations, represent some of the strongest and most genuine examples of real mutual assistance, and some of those centres engage as well in some lobbying for legislation for their communities. One of the largest and most important of them, Make the Road New York, a community organisation with around 25,000 dues-paying members, provides food pantries, takes part in efforts to organise Amazon warehouse workers and carwash workers, as well as domestic cleaners and others, does health and safety for essential workers, and advocates for legislation, including laws to provide undocumented immigrants with access to many of the benefits afforded to US citizens.

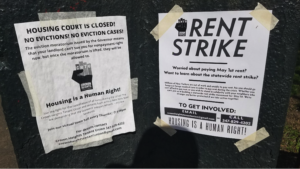

And rent strikes?

As we have noted, the class struggle takes place not only in the workplace but also in communities, and sometimes the fight isn’t against the boss but against the landlord or the bank. The shutdown that threw tens of millions out of work led to what we might call a de facto rent strike, as nearly one third of all renters were unable to pay the landlord on April 1. Others couldn’t rearrange their payments, though banks generally granted extensions. Without much prompting from below, various state governors, legislators, and supreme courts stopped evictions early on, generally to last until June 1 – though when the various orders to stop evictions end, tenants will still owe rent.

Signs at the entrance to a public park in the author’s neighbourhood in Brooklyn.

In any case, community organisers focused on housing saw an opportunity to organise a tenants’ rent strike. So organisations in New York State, Pennsylvania, and California called for a national rent strike on May 1, International Labour Day. In New York City organisers targeted the largest and wealthiest realty companies and some 12,000 people signed a pledge not to pay rent, but that’s a tiny number considering the city has over two million renters. The Los Angeles Tenants Union said that 8,000 of its members would not pay rent, but LA has 5.5 million renters. In New York and some other cities, tenants in some buildings, often buildings with a pre-existing tenants’ union, did strike their landlords. But no mass movement seems to have developed out of the May 1 strike call.

Resurgence of the movement against police violence

The racist police murder of George Floyd, strangled under the knee of a police officer for over eight minutes while gasping, “I can’t breathe,” led to immediate mass protests by thousands at the end of May. While the police chief fired the killer and three other officers who stood by and watched, no charges were brought against any of the officers and the Black community erupted in first in a day of peaceful protest demanding that the officers be charged. Minneapolis mayor Jacob Frey asked, “I’ve wrestled with, more than anything else over the last 36 hours, one fundamental question: Why is the man who killed George Floyd not in jail. If you had done it, or I had done it, we would be behind bars right now.”

When the District Attorney failed to act, a second day of protests in Minneapolis involved riots, looting and arson. The Minnesota State Police (mostly white officers who live in suburban and rural areas) who had been sent into Minneapolis after the second day of rioting arrested a Black CNN reporter and his crew. On the third day, protesters burned down a police station. The governor of Minnesota, Tim Walz, of the Democratic-Farmer-Labour Party, called out the National Guard to suppress the violent protests. At the same time, despite the continuing COVID-19 pandemic, protests by thousands spread beyond Minneapolis to many major US cities: New York, Columbus, Memphis, Denver, Albuquerque, Portland, Oregon, Phoenix and Los Angeles.

The belated arrest on May 29 of Derek Chauvin, the police officer who killed George Floyd, failed to appease protesters’ anger. Indeed, they expressed further outrage that the charge was only the lesser one of third-degree murder, and that none of the other police officers, who stood by and watched as Floyd died, have been charged with any offence.

George Floyd’s death followed two other recent murders of Black people. One was the murder of Ahmaud Arbery by a former police officer and his son. While Arbery, who was out jogging and unarmed, was shot and killed on February 23, the two white killers, one a former police officer, who were not arrested until May 7. The other was the police murder of Breonna Taylor on March 13, when police forcibly broke into her apartment to present a search warrant in a drug investigation and shot her eight times, killing her. No drugs were found in the apartment.

These most recent police murders of Black people resemble the notorious cases in the summer of 2014 of Eric Garner of New York, killed for selling untaxed cigarettes on the street, and Michael Brown of Ferguson, Missouri, who was suspected of petty theft. In both cases the officers who murdered those men walked free. Those two murders ignited the Black Lives Matter movement of that year.

What often began as peaceful demonstrations became violent clashes between demonstrators and police in at least 75 cities where buildings and police cars burned, stores were looted, many people were injured, and at least four were killed. The protests are reminiscent of the ghetto rebellions of the 1960s and 1970s and a more militant version of the Black Lives Matter movement of 2014. In response to the protests, mayors established curfews and called out the riot police, in some states governors called out the state police and the National Guard. President Donald Trump called the Minneapolis protestors, “thugs,” and tweeted that, “When the looting starts, the shooting starts.”

Everywhere the police have violent attacked demonstrators with tear gas and pepper spray, beatings protestors with their batons, and arresting hundreds, Curfews have been implemented in many major cities, yet thus far Black activists and their many white and Latino supporters defiantly assert their right to protest. In response to the protests over Floyd’s killing in Minneapolis, President Trump tweeted, “When the looting starts, the shooting starts”, encouraging further police violence. Trump has said he would declare Antifa to be a terrorist organisation, though there is no such organization and though he has no legal right to do so.

Though we are in the midst of the coronavirus pandemic, infuriated by the racist police murders of Black people, a new multi-racial social movement against racism may be in the process of being born.. Regardless of what comes, the nation-wide rebellion has already left a mark on US politics.

The coronavirus crisis and its economic impact have revealed the enormous economic, racial and gender disparities in society. It has lifted the veil on the relentless exploitation that existed even before this crisis. So far we have not seen this change in consciousness lead to significant mass action, but we’re still early in the crisis, and attempts to reopen workplaces without adequate health protections or with changes in employment security and wages could spark new actions and perhaps on a larger scale. Taken all together, workers’ movements, the mutual aid projects, and the left represent a very small and not very weighty force in American society at this time.

Future prospects

For the next few years workers will face several major challenges. First, unemployment – now at 25 percent – will not improve rapidly and may take years to get down to 10 percent. GDP in the United States will fall by 30 percent according to the chair of the Federal Reserve Bank. Many of America’s largest corporations have been halted or at least stalled: airline manufacture and airlines, shipping companies, cruise lines and hotels. Production of durable goods – cars, stoves, refrigerators, washers and dryers – has already been cut back because unemployment means a lack of consumers for these goods, and likewise with computers. The same is true for wholesale and retail trade; no customers, no trade.

Various surveys suggest that between a third and a half of all small businesses will fail in the next several months. The retail business was already in the period from 2010 to 2019 undergoing what was called a “retail apocalypse,” that is the closing of dozens of major and minor brick and mortar companies with hundreds of stores that had been unable to compete with online stores and delivery services; and now the coronavirus crisis and the shutdown have added to the catastrophe, sweeping away companies like J. Crew and Neiman Marcus. Various other industries have also see large-scale business failures, from restaurants and food chains to cinemas and gymnasiums, some with hundreds of stores. Some 110,000 restaurants out of one million are expected to close permanently and three million restaurant workers have already lost their jobs so far. Small restaurants may simply not survive and big chains may move in and take over, but recovery and employment will still be a long way off.

Historically high unemployment, especially when it first develops, tends to inhibit working class resistance, since workers with jobs hesitate to risk losing the jobs they have by engaging in union organising or strikes. In the United States the Great Depression began with the crash of 1929 and high unemployment followed soon after, but the first big upheavals did not occur until 1933 and they did not culminate until 1937. The two recessions of the late twentieth century, 1973-75 and 1981-82, put a definitive end to the wave of working class activism of the early 1970s and started the nation’s labour movement on its long downward slide. After that union activism, with a few notable exceptions like the Teamsters’ strike against UPS in 1997, didn’t pick up again for almost 40 years, until the 2018 teachers’ strikes. Organising during a period of deep and long-term unemployment will require patience and persistence, waiting for the working class to assimilate the experience, take small steps of resistance, and reconstitute itself for struggle in the coming years.

The fiscal crisis of government at all levels

The government shutdown of the economy has meant that neither employers nor workers are paying taxes, at least not as they did before the crisis. Consequently governments at all levels – cities, counties, water, sewage, and school districts, and states – face an enormous fiscal crisis without the funds to continue to run government, to provide services and to pay workers. Forty-four of the 50 states have laws requiring them to present balanced annual budgets. Since states aren’t allowed to go bankrupt and don’t have the power to print money, only the federal government could actually possibly save the states, but the Republican Senate has refused to do so, at least so far.

As the crisis became clear over the first month or two, government officials announced that they would have to cut their budgets, which meant cutting virtually all services to the public, but particularly the big ticket items like health and education. So throughout the country virtually all state governors and legislators are now contemplating and planning cuts to public education in primary and secondary schools and in public colleges and universities. Many of these proposed cuts will be deep, resulting in layoffs of teachers and other staff.

The unions that represent government workers are some of the biggest in the country: the National Education Association (NEA) has 2.7 million members and its rival the American Federation of Teachers (AFT) has just under one million; the Service Employees International Union (SEIU) has 1.9 million members and its competitor the American Federation of State, County, and Municipal Employees (AFSCME) has about 1.5 million. Some states limit their right to strike. A number of other unions, from the UAW to the CWA and the Teamsters, also organise public employees. The unions representing federal workers, the American Federation of Government Employees (AFGE) with 670,000 members, and the National Treasury Employees Union (NTEU), with 150,000 members, are much weaker unions, forbidden by law from striking. While these unions are large, have great resources and are potentially powerful, they are extremely bureaucratic and the leadership by and large collaborates with management and avoids fights.

New York State faces a 13.3 billion loss in revenue and is demanding cuts from virtually all government agencies. At the enormous City University of New York, with 25 campuses serving 275,000 students, there are 7,800 full-time professors, more than 5,000 professional staff members, and some 12,000 adjuncts who make up the largest share of employees. The Gothamist reports that “A CUNY budget memo distributed to the PSC in April said up to $95.3 million could be cut from the system”. CUNY administrators plan to deal with the crisis with a mass layoff – through letters of non-reappointment – of adjuncts who teach an enormous number of classes. The CUNY union, the Professional Staff Council, says such layoffs are unacceptable, and has launched an ad campaign against the budget cuts, but so far no other action is planned. The situation is similar in the University of Massachusetts system. One non-tenure-track (fixed term) professor there suggests that capping salaries of all university employees at $100,000 or even $150,000 would save those jobs.

Governments at all levels are asking the unions to help them make the budget cuts through furloughs, pay cuts and service reductions, and few so far show signs of resisting. The United Caucuses of Rank–and-File Educators that brings together a number of teacher caucuses believes in principle that schools should only reopen when they are fully funded, without debt, and safe for teachers, staff and students. Yet it is not clear how teachers can convert that ideal into a strategy to stop the budget cuts and to protect the health of everyone who forms part of the educational community. The attack on public employees is playing out right now and so it may be just a little too early to see what’s developing. We may only see resistance movements when schools attempt to reopen in the fall.

What about unemployed organising?

Unemployed organising represented an important factor in the workers’ movement of the 1930s. The organisers of the Unemployed Councils came from the Socialist Party and the Communist Party, particularly the latter. In 1934 socialists organised the unemployed in Toledo to help win the Toledo Auto Lite Strike. The Communists in the unemployed movement fought evictions, restoring evicted tenants to their buildings, and in Minnesota, the Trotskyists cooperated with Farmers Holiday Association to resist foreclosures and the sale of farmers’ land. Usually the unemployed were organised in protest demonstrations and marches to demand relief from the city, state and federal government, so the movement had an inherently political character, making demands on politicians and elected officials. President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s “New Deal” responded at the national level to the pressure from below, creating such programs as the Civilian Conservation Corps and the Works Progress Administration that created jobs for hundreds of thousands.

During the recessions of 1973-75 and 1981-2 the International Socialists (IS), as did other left groups (mostly Maoist then), undertook unemployed organising. In Chicago I was involved with other IS branch members in some attempts at unemployed organising. At that time, we leafleted unemployment offices where we met and talked with workers and invited them to come to meetings of the unemployed so that we could begin organising to make demands for jobs or greater assistance. We found that those who had lost their jobs proved very difficult to keep track of and to keep organised.

The lives of the unemployed are hard, and not just because of loss of income. The principal structure and discipline of their own lives had disappeared with the loss of their jobs and they were often at loose ends. Some unemployed people become depressed; they may turn to alcohol or drugs and self-medicate, they may engage in domestic abuse, taking our their frustrations on their families. Most unemployed workers spent time hustling jobs or doing work outside their usual trade, paid under the table. Our most successful unemployed organising took place among workers who maintained an attachment to their union. The union provided an institution with information – the workers’ names, addresses, and phone numbers – with resources such as meeting halls, and as fellow union members we had something in common. And workers felt they had a right to call upon the union to help them. Still, in truth, we were not very successful in our unemployed organising.

During the economic crisis of 2008, Occupy Wall Street provided a movement that the unemployed and many others in society could relate to. In many cities and towns Occupy Wall Street encampments provided a community and activities of all sorts, including protests to demand assistance for the unemployed. In some places Occupy Wall Street organised “Occupy the ’Hood,” an outreach to Black and Latino communities, and in many places OWS helped to fight evictions. In several cities OWS brought its members out to stay outside the homes of families facing foreclosure, gaining publicity and in a few cases preventing the eviction. Barack Obama’s administration coordinated the national repression of the movement – including the arrest of 8,000 protesters, with some accused of terrorism – effectively ending the movement.

All of those experiences of the 1930s, the 1970s and 80s, and the 2000s suggest that unemployed organising can be done, but it is difficult. History suggests it is most successful when connected to a left political party or to a labour union.

The Trump administration

Donald Trump’s administration is the most right-wing American government in modern history and it represents a dangerous threat to the labour movement. Trump is known for his racist, misogynist and xenophobic views and rhetoric, and for his political platform of “defending” America from Mexican and other Latino immigrants, from Arab and other Muslim “terrorists”, and from Chinese competition. Trump has praised and encouraged the armed white protesters carrying swastikas and Confederate flags who invaded the Michigan legislature demanding reopening. His administration has rounded up tens of thousands of undocumented immigrants and put them in private prisons, it has put children in cages, and was putting asylum seekers in concentration camps – that is until it closed the border to virtually all immigrants. Trump has pledged to make the Republican Party a “workers’ party” – meaning a defender of white men’s jobs against their competitors, Black, Latino, female and immigrant. He has courted the building trades and won the votes of tens of thousands of their members. Trump’s rhetoric and policies work to divide society and the working class.

While he began his career as simply as a racist and corrupt businessman with some racist and right-wing opinions, Trump has evolved in the last few years into a genuine far-right authoritarian figure who has taken control of the Republican Party and disciplined it to his will with the carrot of tax cuts and the stick of presidential condemnation at election time. The Republican Senate follows Trump’s lead and blocks legislation he rejects. Trump’s appointments to the Supreme Court and to other federal courts have transformed the judiciary into something resembling tribunals of the Gilded Age, when rich old white men in black robes defended the interests of rich white men in top hats. Trump’s government is well poised to crush the labour movement, should it begin to act. Everything Trump does, from his trillions of dollars in tax cuts for the rich to his rush to reopen the economy, benefits the right and hurts working people.

Trump ignored many early warnings of the COVID-19 pandemic from a variety of government agencies, from the Centers for Disease Control to the National Security Council. His policies are responsible for the needless death of tens of thousands of Americans in the first few months of the plague; one study suggest that 36,000 lives might have been saved had the government acted quickly and correctly. Now he has lifted the federal shutdown and encouraged state governors to reopen the economy, even though the states don’t meet the guidelines of falling cases and don’t have adequate testing and contact tracing. His reopening order threatens the health and the very lives of workers returning to their jobs at schools, stores and factories.

There is little doubt that as workplaces reopen, fights over the protection of workers’ health will be at the center of class struggle, as they already are in some places. The pandemic and the shutdown have taken a toll, but they now provide an opportunity to rebuild the American labour movement from the bottom up. While the challenges will be great, working-class resistance is growing, and socialists with a rank-and-file strategy and a class struggle perspective are involved in the fight.