Seemingly overnight, politicians are tripping over themselves as they clamor for prison reform in a climate where cases of police murder and prison abuses have drawn thousands in protests onto the streets. Today, few would doubt that America’s criminal justice system is racist and unfair. Moreover, many now point to the hypocrisy of mass incarceration in a country that touts itself as a global leader and standard bearer of democracy in the “free” world. It is within this climate that prison abolitionists need to challenge the piecemeal reforms and link up with criminal justice activists to build a movement to abolish America’s prisons.

Far from some pie in the sky idea as some critics would maintain, the road to prison abolition is the only humane and practical alternative to a system that locks people in cages as a solution to poverty and mental illness. American political icon, academic and author Angela Davis asks a fundamental question: “why do we take prisons for granted?” in her book Are Prisons Obsolete?”[1]

Davis asks that we put prison abolition in the same context as the movement to abolish the death penalty, Jim Crow, and Slavery, arguing that there was a time when abolition of those racist institutions seemed insurmountable. Key to any argument for prison abolition is a greater awareness of the perpetuation of systematic racism that Black Lives Matter activists have argued is at the root of the murder of thousands of Black men and women in the last few years.

As author Khalil Gibran Muhammad points out in Condemnation of Blackness: Race, Crime and the Making of Modern Urban America, the criminalization of African Americans reaches back to the end of Reconstruction. Over the last four decades, systematic racism has been a key mechanism in the build-up of America’s carceral state in order to divert workers attention away from growing socio-economic disparities. As Mike Davis exclaims in his book City of Quartz, nowhere have we seen such a growing gap between rich and poor without a revolution.

It is, therefore, a shock that even the racist demagogue President Trump, who ran a tough on crime campaign, has introduced what he calls “groundbreaking criminal justice reform,” in the First Step Act. The act is not in isolation but in the context of politicians of all stripes introducing laws aimed at reducing the prison population.[2] More significantly, because the expansion of the carceral state has not improved workers living standards or seen any reduction in crime, and has actually been met with increasing class polarization and rising recidivism rates,[3] many are questioning the legitimacy of mass incarceration and calling for genuine reform.

Two decades ago, few would have predicted that politicians from both sides of the isle would use the rhetoric of prison reform to garner votes. President Bill Clinton had doubled the rate of incarceration, created stricter sentencing, and expanded possible death penalty convictions by 50 percent. The Three Strikes Law was introduced in California and spread to other states.[4]

Hillary Clinton had coined the phrase “the Black Predator” to stir up white voters by blaming Blacks and Latinos for crime, and Senator Phil Gramm was calling prisons country clubs. The racist rhetoric fueled the largest prison construction in world history and decimated communities of color. Today, of the 2.2 million in prison, over half are Black or Latino.

Bill Clinton didn’t invent the use of racism to build up the criminal justice system he just expanded it. Republican presidential candidate Barry Goldwater used “law and order” as a centerpiece for his 1964 campaign against Lyndon B. Johnson. Johnson admired the strategy enough to incorporate it into his “war on crime.” Nixon also used the law-and-order theme as a way to distract people’s attention from issues, such as the rapidly deteriorating economy and the failing war in Vietnam. Nixon appealed to voters’ fears of social unrest, especially on white fears of Black street crime. By the late 1970s, nearly half of all Americans were afraid to walk home at night, and 90 percent responded in surveys that the US criminal justice system wasn’t harsh enough.[5]

But it was Ronald Reagan who “became a master of linking the law-and-order theme with covert, and sometimes not so covert, racial messages,” writes author and activist Phil Gasper. Reagan described the Black ghetto rebellions of the 1960s as “riots of the law breakers and the mad dogs against the people.” On a radio commercial in the same period Reagan warned: “[E]very day the jungle draws a little closer. Our city streets are jungle paths after dark…. The man with the badge holds it back.[6]

After California governor Jerry Brown signed into law a new statute in 1976 abolishing parole—which read in part, “The purpose of imprisonment is punishment”—a series of states followed suit with similar laws, including some that lengthened prison sentences. New York state passed stringent mandatory sentencing laws, known as the Rockefeller Drug Laws. Thirty-six other states enacted similar “reforms.”

The tough-on-crime juggernaut gained momentum under President Reagan—accelerated qualitatively by a new campaign against illegal drugs, in particular, crack cocaine. Spending for the war on drugs skyrocketed. In 1980, the federal budget for this war was $1 billion. Today, it’s more than $17 billion.[7] In the Reagan and Bush years, spending on employment programs was slashed in half, while spending on corrections increased by 521 percent. In this same period, the chances of being arrested for a drug offense increased by 447 percent—even though statistics showed a considerable decline in drug use.[8]

In 1984, Congress enacted the Sentencing Reform Act, eliminating parole for all federal crimes committed after November 1, 1987, and curtailing the discretion of judges to set sentences. Federal mandatory minimum sentences for drugs came in 1986 and 1988, with the Anti-Drug Abuse Act and the Anti-Drug Abuse Amendment Act respectively. The 1986 act was passed by a vote of 378 to 16 by a Democratic-controlled House. The act established mandatory six- and ten-year prison terms for drug dealing, as well as the now-famous 100-to-1 crack-to-cocaine ratio, in which possession of 5 grams of crack cocaine triggered the same prison sentence as possession of 500 grams of powder cocaine. A life sentence now requires the sale of just 3.3 pounds of crack. “By 1995…the average federal prison term served for selling crack cocaine was nearly eleven years. For homicide, by comparison, the national average was barely six.”[9]

These drug laws led to a massive increase in the U.S. prison population. Federal prosecutions for non-drug offenses increased by 4 percent from 1982 to 1988. For drug offenses, federal prosecutions increased by 99 percent.

The majority of those held in federal prison for immigration and drug offenses are people of color. Black men have a 1 in 3 chance of being incarcerated and for Latinx males it is 1 in 6, compared to white males at 1 in 17, Black women are a startling 1 in 18 and for white women the ratio is 1 in 111. The targeting of Black youths by the police has been met with a drastic increase in incarceration rates.

The human toll on Black and Latinx lives from the incarceration of 1.2 million people of color, the decimation of Black and Brown communities, and the murderous assaults by police of Black and Latinx men and women is incalculable. A smaller minority of incarcerated people are Native American and Asian, the rest are mainly white and working class. There are few rich people in prison and white-collar crime goes virtually unpunished.

The most influential book in recent years is The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness. Published three years before the official beginning of the Black Lives Matter movement in response to the murder of Trayvon Martin in 2013, author and civil rights attorney Michelle Alexander lays down a fortuitous gauntlet in her claim that America’s criminal justice system is a form of racial apartheid comparable to the Jim Crow era born at the end of Reconstruction. Cornel West called it, “the secular bible for a new social movement in early twenty-first century America.” “Once you have read it,” he continues, “you have crossed the Rubicon and there is no sleep walking.”[10] Paul D’Amato, former editor of the International Socialist Review concurs: “The fight against racism…cannot be separated from the class struggle as a whole. Only by challenging oppression in all its forms can workers unite and become the threat to capitalism that they must become if we are to win a better world.”[11]

Incarcerating the have-nots isn’t a new trend. The penitentiary was born not simply as a reform away from corporal punishment, but as a means for the ruling class to control the emerging impoverished working class that was growing up alongside the abundance of 19th-century capitalism–as well as the Black population freed after the end of slavery. “There is no very great danger of a rich man going to jail,” said the progressive lawyer Clarence Darrow to a group of Cook County Jail inmates in 1902: “First and last, people are sent to jail because they are poor.”[12]

And although America has seen its first dip in incarceration rates in twenty years, at 2.2 million, it still holds the ignominious title of the World’s biggest jailer, incarcerating at a rate 7 percent higher and imprisoning more people than China and Russia. The United States holds more people in its prisons than were killed in the Vietnam War.[13] And the numbers hide the additional 5 million who are in the carceral state’s grip most of whom are on probation and parole and the gross imprisonment of migrants along U.S. Mexican border.[14]

Youth incarceration and solitary confinement

Much of the activist and media spotlight has been aimed at prisoners and in particular juveniles who face years in solitary confinement.

The high-profile Kalief Browder story exposed the nightmare on primetime of what it’s like to be a teenager living alone 23 hours a day seven days a week in a 6-by-9 foot cell. In addition to being beaten by guards and other inmates, all captured on video surveillance tape, Kalief spent three years as a teenager at Rikers—two in solitary confinement—without ever standing trial. Thanks to activists who kept up protests and press conferences the case got national attention, which led to the plan to close Rikers under the supervision of Elizabeth Galazer, Director of New York City’s Mayor’s Office of Criminal Justice.

All of this was too little, too late for Kalief, who committed suicide after being released without charge at home using a hangman’s rope he had learned to tie at Rikers Island. As his mother, Venida Browder, recounted at a press conference with Speaker Melissa Mark-Verito in 2016:

Physically, he was here, but mentally, he was still in Rikers. The solitary confinement really messed him up. It made him very paranoid. He was terrified of ever having to go back to Rikers. He felt that people were police plants, trying to get him. He even told me…“I don’t know if I can trust you.”[15]

Kalief’s nightmare is just the tip of the iceberg. Over half of all juvenile suicides occur in solitary. Over 9,000 (1 in 5) juveniles haven’t been found guilty of any charge and are locked up awaiting trial. Nine-hundred are in long-term facilities, and only a third are charged with violent offenses. Juveniles are more likely to end up in solitary in adult facilities because by law they have to be separated from the adult population. The Juvenile Law Center reported that hundreds if not thousands of youth are kept in solitary and that juveniles in solitary are typically Black or Latino, often do not receive a disciplinary hearing before they are placed in isolation, and can be deprived of medical treatment, showers, eating utensils, reading and writing materials, mattresses, and sheets.

High profile cases such as Browder’s have led some states to end the use of solitary for juveniles because it violates the Eighth Amendment on the prohibition of Cruel and Unusual Punishment. President Obama banned the use of solitary for juveniles in the Federal prisons, a largely symbolic move given that there were only 26 juveniles held in federal prisons at the time. In spite of the rush to reform and in light of Obama’s ban and op-ed piece stating that solitary for juveniles was “an affront to our common humanity,” there is still a long way to go, as columnist Eli Hager reminds us: that “for youth advocates, ending juvenile solitary will take more work. Twenty-three percent of juvenile facilities nationally use some form of isolation, according to a 2014 study by the U.S. Department of Justice.[16]

The threat of solitary confinement, including temporary confinement in Administrative Segregation and security housing units, is one of the key punitive mechanisms used by prison officials to control individual prisoners and the prison population as a whole. In an article in The Atlantic, Natalie Chang says the “paths that lead to time in solitary confinement vary from institution to institution, but they are also the result of a criminal justice system that emphasizes control over rehabilitation.[17]

The situation of juveniles in prison is particularly egregious. 53 thousand are held in facilities away from home, two thirds of which are in the most restrictive facilities. In a 2017 press release for the Prison Policy Initiative, Wendy Sawyer asks, how many of the 18,000 children and adolescents in juvenile detention centers should really be there? According to government guidance, “…the purpose of juvenile detention is to confine only those youths who are serious, violent, or chronic offenders.” Yet over 5,000 youths are held in detention centers for these same low-level offenses.”[18]

The sheer numbers of all individuals in solitary confinement is staggering. According to the Bureau of Justice’s 2011–2012 study, nearly 20 percent of prison inmates and 18 percent of jail inmates (approximately 240,000) had spent time some time in restrictive housing, including disciplinary segregation, administrative segregation involving isolation and little out-of-cell time. The characteristics of those who are thrown into solitary confinement is even more disturbing. For example, younger inmates, inmates without a high school diploma, and lesbian, gay, and bisexual inmates were more likely to be in restrictive housing than older inmates, inmates with a high school diploma and heterosexual inmates.

The use of solitary confinement became front page news in 2013, when the largest hunger strike in California’s history began in Pelican Bay’s notorious Security Housing Unit (SHU) and spread to prisons throughout California. Prisoners were protesting inhumane conditions and the lack of any step-down program that would allow prisoners to get out of solitary confinement. Thousands of SHU prisoners had spent years in solitary confinement some even decades. One strike leader and former prisoner, Joey Villareal, a leader of the Free Aztlan Movement, says “living there was hell. Nice and bright was one of the ways they tortured us. We never saw any color. Inside, egg shell white. Outside eggshell white, white boxers, tee shirts, jump suits, everything we see white and bright lights left on 24/7.”

Thousands of SHU prisoners had spent years in solitary confinement—some even decades. Their struggle won the release of most of the prisoners and the dismantling of the SHU. Nevertheless, there remain security housing units throughout the state of California and nationwide where prisoners to this day are serving in isolation.

The case of Sandra Bland received national attention after she committed suicide in solitary in the notorious Harris County Jail after being held for a routine traffic stop. Her arrest went viral and the officer was dismissed after everyone saw her horrifying arrest video. As the Nation reports, Sandra posted on her Facebook years before, “I’m here to change history.” Little could she have imagined that her death would spark national protests and documentaries as the world asked, “What happened to Sandra Bland?” by many who doubted she actually committed suicide.

High profile cases such as Sandra Bland and Kalief Browder, coupled with large-scale protests against the use of solitary confinement have exposed the hypocrisy of a prison system that calls itself rehabilitative. They have led to a flurry of reforms around the use of solitary confinement but have not put an end to its widespread uses. Today, hundreds of thousands languish in solitary confinement on any given day with little hope of release some serving years in isolation. In spite of the preponderance of evidence that solitary confinement drives people insane and has the propensity to make prisoners more violent, solitary remains as the main mode of discipline within America’s prison system.

The incarceration of the mentally ill has also garnered attention. It is estimated that one third of all prisoners are mentally ill and that America holds over two million mentally ill individuals in its prisons, now commonly referred to as the New Asylum. According to the National Alliance of Mental Illness, 83 percent of individuals receive little to no treatment in prison. Mentally ill individuals experience more brutalization and are thrown into solitary more often because of challenges in navigating each prison’s strict codes of conduct.

From reform to abolition

It is within this atmosphere of greater awareness and a call for genuine reform that Angela Davis, American political icon, asks in an interview with Dylan Rodriguez, how do we stop taking the prisons for granted and see the urgency of building a prison abolition struggle within a reform movement. She explains that “it is when people struggle for reforms that such awareness can lead to the asking of fundamental questions about the necessity of such brutalities and the imagining of a better world without racism and incarceration.”[19]

Davis highlights why fights to reform prisons shouldn’t be separated from the fight for prison abolition:

“The most difficult question for advocates of prison abolition is how to establish a balance between reforms that are clearly necessary to safeguard the lives of prisoners and those strategies designed to promote the eventual abolition of prisons as the dominant mode of punishment….I do not think that there is a strict dividing line between reform and abolition. For example, it would be utterly absurd for a radical prison activist to refuse to support the demand for better health care inside Valley State, California’s largest women’s prison, under the pretext that such reforms would make the prison a more viable institution. Demands for improved health care, including protection from sexual abuse and challenges to the myriad ways in which prisons violate prisoners’ human rights, can be integrated into an abolitionist context that elaborates specific decarceration strategies and helps to develop a popular discourse on the need to shift resources from punishment to education, housing, health care, and other public resources and services.”[20]

The history of prisoner reform movements adds credence to Davis’ claims, but there are others who would disagree with Davis’ conclusions. Roger Lancaster, a professor of Anthropology and Cultural Studies at George Mason University and author of Sex Panic and the Punitive State writes in “How to End Mass Incarceration,” published in Jacobin magazine, that prison reformers should reject Angela Davis Are Prisons Obsolete? Lancaster claims that, “abolitionism promises a heaven on-earth that will never come to pass.”[21] He counter poses prison reform to prison abolition, the latter which, he argues, is “unlikely to win broad public support.”

Lancaster is wrong to accuse prison abolitionists of being “remarkably innocent of history,” or that their position is that we must “choose between abolition and reform, while discounting reform as a viable option.”

One only has to look back to the largest prison rebellion in U.S. history in 1971 at the Attica Correctional Facility in upstate New York to see reforms won by those with revolutionary ideals. More recently, it was the 2016 prison abolition movement that generated the largest prisoner work stoppage in U.S. history. The 2013 Pelican Bay State Prison hunger strike, led in part by a sizable number of revolutionaries, resulted in a near-dismantling of its notorious Security Housing Unit (SHU), the passage of multiple new sentencing laws which have gained the release of thousands of prisoners, and an educational reform movement inside the prisons that is challenging the “lock them up throw away the key” model in California. As Joey Villareal states, “the Pelican Bay Hunger strike began as an isolated fight to end solitary confinement helped people become conscious about state repression and helped forge a new abolitionist movement.”

Lancaster has his own utopian dreams. He recommends that the United States could adopt Finland’s rehabilitative system. To suggest that the U.S. would move to a model like Scandinavian prisons that “have no walls and allow prisoners to leave during the day for shopping” is ludicrous.

Lancaster is not the only one calling for a kinder gentler prison system. Philanthropist, Frank Gehry, invited an audience of architects and students, corrections officials and campaigners for criminal justice reform to assemble at the Yale School of Architecture for the finale of Gehry’s semester-long “studio” on architecture and mass incarceration. A dozen students would present their projects—designs for a humane prison—to a jury consisting mostly of Friends of Frank and funded by George Soros. Christopher Stone, the outgoing president of Soros’s Open Society Foundation said, “We asked Frank, what would it mean to design a maximum-security prison if you treated the corrections officers and the prisoners as the clients instead of the state bureaucracy.” During the planning students went to Finland and Norway, but it proved too idealistic and impractical to most who wondered how a prison in the United States would work without walls and bars.

Instead of imagining a kinder and gentler prison, Angela Davis suggests that no prisons would be better to reduce crime more than the current state of mass incarceration. As a second alternative she proposes, “building the kind of society that doesn’t need prisons.” She calls for a massive redistribution of “power and income” by taking resources away from the prisons and moving them into social service agencies:[22]

She calls for the “demilitarization of schools, revitalization of education at all levels, a health system that provides free physical and mental care to all, and a justice system based on reparation and reconciliation rather than retribution and vengeance.”[23]

Lancaster rejects this idea: “While the state-sanctioned brutality that now marks the American criminal justice system has motivated many activists to call for the complete abolition of prisons, we must begin with a clearer understanding of the complex institutional shifts that created and reproduce the phenomenon of mass incarceration.”

Lancaster fails to see that the “punitive turn” that he argues took place in the early 1970s in the U.S. penal system was not just a “cultural shift,” but a refashioning of a racist tool that does not “exceed,” but is integral to the survival of the penal system. His blind spot is to see only institutional effects rather than the more dynamic changes that have occurred within America’s prison system. He states: “The American prison system is brutal and unjust. But the rhetoric of prison abolition won’t help us end its depravities.”

In couching his understanding of a single “punitive turn,” he misses the reform waves that swept through American prisons in the early seventies. Two weeks after the murder by prison guards of Black Panther and revolutionary George Jackson at California’s San Quentin State Prison, one of the most significant prisoner rebellions erupted in a demand for better living conditions and political rights in upstate New York. Heather Ann Thompson recounts in Blood in the Water: A History of the Attica Prisoner Uprising what an era of educational reforms had on the Attica prisoners.[24] She explains how in the area of education “instructors were instrumental in inspiring Attica’s incarcerated to see the world both within and outside of Attica’s walls as inexorably linked.[25]

This reform wave paralleled the Black Power movement that swept the country in the late sixties and early seventies. The Attica rebellion and prisoner reform movement were a reflection of the renewed radicalism outside the prisons. Their chant: “We are Men! We are not beasts and we do not intend to be beaten or driven as such” from the prison yard echoed the sentiments of the Black Power movement against police brutality and for better urban living conditions.

The gains won through the early seventies prison reform wave lasted until 1992 when President Bill Clinton introduced his notorious Omnibus Crime Bill that brought in stricter sentencing, an increase in death punishable crimes, and an elimination of Pell Grants. This attack was part of a much broader attack on workers to destroy the social safety net by scapegoating African Americans to divert people’s attention away from the draconian cuts.

Clinton’s policy of ending welfare as we knew it in exchange for workfare workers was an attack on all workers, especially unionized workers. In understanding the age of mass incarceration as a reflection of larger societal forces, there is hope that as societal forces such as the Black Lives Matter movement challenge systematic racism, the prisons themselves will again become hotbeds of radicalism that can unite with the resurgence of anti-racists struggles now gaining steam across America

Race, Class and Prisons: It’s Personal

I know the only humane and practical solution to America’s racist criminal justice system is abolition from my years of teaching in California prisons and from my decades-long fighting on the streets of New York City and Chicago, shoulder to shoulder with families and friends of those whose loved ones had been brutalized by the system.

My first exposure to police brutality was with the case of Leonard Lawton, an unarmed fifteen-year old Black youth who was shot in the face from ten feet away while hanging out in his building at the Polo Grounds Housing Projects of New York City’s Harlem. I can still see the stunned Mrs. Lawton sitting quietly on the end of the sofa in her empty apartment with her hands in her lap as I began to interview her for a story for Socialist Worker the day after a cop killed her son. After the interview, I met Leonard’s father and brother, both of whom spoke on numerous panels and attended rallies organized by the International Socialist Organization.

After covering stories equally horrific to Leonard Lawton, all inflicted on Black and Brown, none with indictments for perpetrators. I became increasingly aware of the systematic nature of police abuses. I also became inspired by families willing to take to the streets regardless of police reprisals.

When I moved to Chicago in 1998, I shifted focus to a group of men railroaded on to death row on the basis of confessions extracted under torture by veteran detectives led by Police Commander Jon Burge. The tortures included electro-shock, suffocation and severe beatings along with the cover up by cops, supervisors, judges, states attorneys and mayors. Marlene Martin, Director of the Campaign to End the Death Penalty, asked me to coordinate what came to be known as the Death Row Ten Campaign. Through the help of lawyers and the tireless marches, rallies, press conferences and forums with family members, we were able to fuel a growing wrongful conviction movement. It finally reached Governor George Ryan who pardoned four of the Death Row Ten and commuted all 176 death sentences to life without parole.[26]

The sheer viciousness of the police torture scandal that led to hundreds being sent to prison on the basis of tortured confessions, and the depth of the conspiracy to cover it up, convinced me of the need for abolition. Our victory in Illinois also showed me how that ordinary people can prevail over the most repressive aspects of the system.

Thus when I first stepped onto a California prison yard as an instructor in 2007, I was already committed to abolishing the prison system. I saw our reform work as but a stepping stone to help raise expectations among prisoners for a broader fight. As the Co-Founder and Director of Feather River College’s Incarcerated Student Program, I brought a handful of instructors behind the prison walls.

The first time I taught a literature class to a student at High Desert State Prison, a level four maximum security prison, I was accompanied by one guard beside me and another perched behind. I peered through the dusty Plexiglas window of the steel door into the eyes of my student who was surrounded by darkness in his tiny cell with his cell mate on the bunk behind him. As he I responded to my question about extended metaphor in Macbeth, the space around us seemed to melt away. I was stunned by the capacity of the human mind to transcend even the most barbarous of circumstances. When I walked into my first classroom at Central California Women’s Facility, the world’s largest female prison, I saw a packed room of women sitting up straight each with a stack of books in their laps and a gleam in their eyes transformed from prisoners to students.

My opportunity to bear witness to this capacity of human beings to strive for some immeasurable good in the face of the most repressive of circumstances changed my life. Through all I’ve beheld, including men and women living in over heated or freezing tiny cells and humans in upright cages, and all the stories I’ve heard about beatings and murder by guards and people wearing only boxer shorts in driving bitter rain forced to spend hours in cages, and the sheer callousness I’ve seen displayed by the custodial and service staff to the men and women forced to abide by their dehumanizing rules, I remain steadfast in my conviction that these men and women have an indomitable will and the ability to rise up against their oppressors.

A recent interview with Nube Brown, a leading member of California Prison Focus and facilitator for Liberate the Caged Voices explains how working with prisoners inside the system should go beyond simple reforms [27]: “we have to do that work on the road to abolition. I don’t consider that reform. It’s what they are asking for on the inside. It’s not something that you do, it’s the place that you land. It’s not about reform but about building.”

Prison abolitionists are right to draw such conclusions about the potential of real human beings’ ability to win through struggle rather than waiting for some “emergent institution.”[28] The only practical solution is to build an abolitionist movement within the struggles to win prison reforms. In doing so, activist will finally tear down America’ racist prison system brick by brick and free those who reside in its cages once and for all. The main task of socialists today should be to help link prison reform movements to a broader anti-racist movement that exposes the lie of the United States as the standard-bearer of democracy and fights to end the capitalist society that gave birth to such hypocrisy in the first place.

Notes

[1] Angela Yvonne Davis. Are Prisons Obsolete? (New York: Seven Stories Press, 2003).

[2] The First Step Act is a refinement rather than a reform of Federal prisons. It is divided into six Titles I. Recidivism Reduction; II. Bureau of Prisons Secure Firearms Storage; III. Restraints of Pregnant Prisoners Prohibited; IV. Sentencing Reform; V. Reauthorization of Second Chance Act of 2007; and VI. Miscellaneous Criminal Justice. That include, prohibition of anything but temporary juvenile solitary confinement; important data collection on solitary confinement, pregnant women, and medical care, treatment for opioid and heroin; notification to families and partners of the terminally ill and/or mental incapacity to apply for sentence reduction; compassionate release; home confinement for low risk prisoners; and transfers closer to families. The act does not offer sentencing reform but does reduce Life without Parole sentences to 25 to life.

[3] A Bureau of Justice Statistics study from 2005 to 2010 about two-thirds (67.8 percent) of released prisoners were arrested for a new crime within 3 years, and three-quarters (76.6 percent) were arrested within 5 years, compared to BJS study from 2009 to 2014, when an estimated 68 percent of released prisoners were arrested within 3 years, 79 percent within 6 years, and 83 percent within 9 years. Bureau of Justice Statistics, 2005, 2017, May 23, 2018.

[4] The Three Strikes Law, first introduced in California in 1994, impose harsher sentences after someone has been convicted of certain felonies three times. In a notorious case in 1996, a California man with prior convictions for robbery and attempted robbery was given 25 years in prison for stealing a slice of pizza.

[5] Manning Marable, “Racism, prisons, and the Future of Black America,” ZNet Daily Commentaries, August 31, 2000, at www.zmag.org.

[vi] Phil Gasper, “Cruel and unusual punishment: Politics of crime in the U.S.,” International Socialist Review, Spring 1995, 65.

[7] William J. Chambliss. “Misperceptions of Crime,” introduction, Power, Politics, and Crime (Colorado: Westview Press, 1999), 7.

[8] See Marc Mauer (The Sentencing Project), Race to Incarcerate (New York: New Press, 1999).

[9] Joseph T. Hallinan, Going up the River: Travels in a Prison Nation (New York: Random House, 2003), 40.

[10] Michelle Alexander. The New Jim Crow, 186.

[11] Paul D’Amato. “They Divide Both to Conquer Each,” International Socialist Review, March 22, 2002.

[12] Clarence Darrow. Crime and Criminals: Address to the Prisoners in the Cook County Jail & Other Writings on Crime & Punishment (Chicago: Charles H. Kerr, Clarence Darrow 2000), 15, 16.

[13] Bureau of Justice Statistics.

[14] Peter Wagner and Wendy Sawyer. “Mass Incarceration: The Whole Pie.” Prison Policy Initiative, March 14, 2018.

[15] Alysia Santo, “What Kalief Browder’s Mother Thinks Should Happen to Rikers,” The Marshall Project, February 17, 2016, https://www.themarshallproject.org/2016/02/17/what-kalief-browder-s-mother-thinks-should-happen-to-rikers.

[16] Eli Hager. “Ending Solitary for Juveniles: A Goal Grows Closer.” The Marshall Project, August 1, 2017.

[17] Natalie Chang. “This Is Solitary.” The Atlantic, https://www.theatlantic.com/sponsored/spike/this-is-solitary/1245/.

[18] Wendy Sawyer. “Youth Confinement: The Whole Pie.” Press Release, Prison Policy Initiative, February 27, 2018.

[19] Angela Davis. “The Challenge of Prison Abolition: A Conversation,” https://www.historyisaweapon.com/defcon1/davisinterview.html.

[20] Angela Y. Davis. “The Challenge of Prison Abolition: A Conversation.”

[21] Roger Lancaster, “How to End Mass Incarceration,” Jacobin Magazine, August 2017, https://www.jacobinmag.com/2017/08/mass-incarceration-prison-abolition-policing.

[22] Angela Y Davis. Are Prisons Obsolete?, 107.

[23] Angela Y Davis. Are Prisons Obsolete?, Ibid.

[24] Heather Ann Thompson. Blood in the Water: The Attica Prison Uprising of 1971 and Its Legacy (New York: Vintage, 2016).

[25] Ibid., 28.

[26] Marvin Reeves, Mark Clements, Ronald Kitchen, in collaboration with Stanley Howard. Tortured by Blue: The Chicago Torture Conspiracy (Bloomington: Balboa Press, 2018).

[27] Nube’s organization is one of many prisoner rights organizations that also fight for abolition and see it as a part of a more systemic problem. California Prison Focus, Critical Resistance, and Common Justice are just a handful of existing organizations.

[28] Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor. From #Black Lives Matter to Black Liberation (Haymarket Books, 2016).

This article has been updated, 8/17/2020, to correct the spelling of Kalief Browder’s name.

Clearly the attacks on Norwegian and Japanese tankers off the Gulf of Oman on Thursday 14 June increase the risk of a miscalculation leading to military clashes in the region. However, these attacks were probably not carried out by any of the Iranian regime’s armed forces, not even the Pasdaran or a section of the Pasdaran (though that can’t be completely ruled out).

Clearly the attacks on Norwegian and Japanese tankers off the Gulf of Oman on Thursday 14 June increase the risk of a miscalculation leading to military clashes in the region. However, these attacks were probably not carried out by any of the Iranian regime’s armed forces, not even the Pasdaran or a section of the Pasdaran (though that can’t be completely ruled out).

The “Stonewall riots”, which began on 28 June 1969 in New York, marked the start of the modern lesbian and gay rights movement.

The “Stonewall riots”, which began on 28 June 1969 in New York, marked the start of the modern lesbian and gay rights movement.

Norman Thomas was the most prominent spokesperson for the Socialist Party of America in the 1930s and 1940s. He ran six times for president on the SP ballot line. Recently,

Norman Thomas was the most prominent spokesperson for the Socialist Party of America in the 1930s and 1940s. He ran six times for president on the SP ballot line. Recently,

President André Manuel López Obador has deployed several thousand troops of the newly created National Guard to the state of Chiapas to deter Central American immigrants from entering Mexico from Guatemala and in that way to please U.S. President Donald J. Trump. There is fear that not only will the National Guard repress the Central Americans but that it will also be used against the Zapatista Army of National Liberation, its communities, and other indigenous peoples. The following statement, which we have translated here, has been issued by Mexican and international individuals and organizations. – Dan La Botz

President André Manuel López Obador has deployed several thousand troops of the newly created National Guard to the state of Chiapas to deter Central American immigrants from entering Mexico from Guatemala and in that way to please U.S. President Donald J. Trump. There is fear that not only will the National Guard repress the Central Americans but that it will also be used against the Zapatista Army of National Liberation, its communities, and other indigenous peoples. The following statement, which we have translated here, has been issued by Mexican and international individuals and organizations. – Dan La Botz

This week a fabricated case against Russian anti-corruption journalist Ivan Golunov was dropped, following a campaign by colleagues and the public. It presents an embarrassing setback for president Vladimir Putin, who in response has called for the

This week a fabricated case against Russian anti-corruption journalist Ivan Golunov was dropped, following a campaign by colleagues and the public. It presents an embarrassing setback for president Vladimir Putin, who in response has called for the

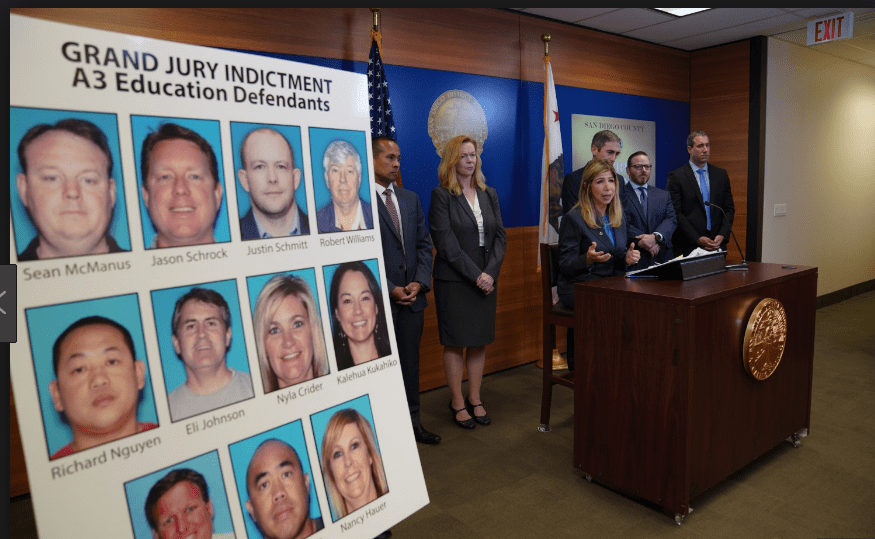

Charter schools are big business opportunities and lax oversight rules make them ripe for financial manipulation and outright theft. The latest

Charter schools are big business opportunities and lax oversight rules make them ripe for financial manipulation and outright theft. The latest

A recent article, written by Abigail Gutmann-Gonzalez and Keith Brower Brown, in the Bread and Roses caucus’s blog, The Call, asserts that the East Bay DSA’s campaigns have been a remarkable success. The title of this essay, “Lessons from The East Bay,” purports to dissect the chapter’s campaigns thus far.

A recent article, written by Abigail Gutmann-Gonzalez and Keith Brower Brown, in the Bread and Roses caucus’s blog, The Call, asserts that the East Bay DSA’s campaigns have been a remarkable success. The title of this essay, “Lessons from The East Bay,” purports to dissect the chapter’s campaigns thus far.

Recently

Recently

Draconian legislative attacks on abortion access in Georgia, Ohio and Alabama require a renewed defense of women’s and trans men’s bodily autonomy. The Supreme Court cannot be relied on to provide this defense under any circumstances. The American left should hear the call to defend Roe v. Wade and come back with a more radical demand: abolish the Supreme Court.

Draconian legislative attacks on abortion access in Georgia, Ohio and Alabama require a renewed defense of women’s and trans men’s bodily autonomy. The Supreme Court cannot be relied on to provide this defense under any circumstances. The American left should hear the call to defend Roe v. Wade and come back with a more radical demand: abolish the Supreme Court.

Mexico’s president Andrés Manuel López Obrador (AMLO), a left-of-center populist in office for only six months, finds himself under enormous pressure from the United States—and he is yielding. U.S. President Donald Trump has demanded that AMLO’s government do more to stop the flow of Central American migrants fleeing poverty and violence in their own countries and passing through Mexico and to seek asylum in the United States, threatening Mexico’s government with a tariff of 5 percent and possibly rising to 25 percent. Such a a tariff would be devastating to the Mexican economy, and, in fact, to the U.S. economy as well.

Mexico’s president Andrés Manuel López Obrador (AMLO), a left-of-center populist in office for only six months, finds himself under enormous pressure from the United States—and he is yielding. U.S. President Donald Trump has demanded that AMLO’s government do more to stop the flow of Central American migrants fleeing poverty and violence in their own countries and passing through Mexico and to seek asylum in the United States, threatening Mexico’s government with a tariff of 5 percent and possibly rising to 25 percent. Such a a tariff would be devastating to the Mexican economy, and, in fact, to the U.S. economy as well.

Aaron Bastani

Aaron Bastani

Picturing the Proletariat: Artists and Labor in Revolutionary Mexico, 1908-1940.

Picturing the Proletariat: Artists and Labor in Revolutionary Mexico, 1908-1940.

I greet with great pleasure the Arabic translation of Marx at the Margins. As readers will see, the book takes up three intertwined issues within Marx’s thought, all them in relation to capital and the struggle for its transcendence: (1) race, ethnicity and class within a particular nation; (2) nationalism and national emancipation; (3) colonialism and the resistance to it.

I greet with great pleasure the Arabic translation of Marx at the Margins. As readers will see, the book takes up three intertwined issues within Marx’s thought, all them in relation to capital and the struggle for its transcendence: (1) race, ethnicity and class within a particular nation; (2) nationalism and national emancipation; (3) colonialism and the resistance to it.

This blog post is based on a presentation on chapters 2 and 8 of Terry Eagleton’s

This blog post is based on a presentation on chapters 2 and 8 of Terry Eagleton’s

Saturday, June 1, 2019

Saturday, June 1, 2019

The Green New Deal (GND), drawn up by Congresswoman Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez and Ed Markey, is the most ambitious and comprehensive program to deal with climate change ever made by political representatives to Congress and the U.S. public. It calls for making dramatic changes within the next ten years to end our reliance on fossil fuels that are warming the planet at an alarming rate. But it is not only about curbing carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions: it is most of all a proposal to set us on a path of creating an ecologically sustainable society.

The Green New Deal (GND), drawn up by Congresswoman Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez and Ed Markey, is the most ambitious and comprehensive program to deal with climate change ever made by political representatives to Congress and the U.S. public. It calls for making dramatic changes within the next ten years to end our reliance on fossil fuels that are warming the planet at an alarming rate. But it is not only about curbing carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions: it is most of all a proposal to set us on a path of creating an ecologically sustainable society.

Microsoft has joined oil-imperialists James Baker and George Shultz’ Climate Leadership Council (CLC). Their plan is to slap a $40 per ton tax on carbon emissions. In trade, it blocks further regulation, including liability, and disempowers alternative energy research.

Microsoft has joined oil-imperialists James Baker and George Shultz’ Climate Leadership Council (CLC). Their plan is to slap a $40 per ton tax on carbon emissions. In trade, it blocks further regulation, including liability, and disempowers alternative energy research.