Over the last five years, Black Lives Matter has served as a broad banner uniting citizens from all walks of life against the most egregious and visible use of police force against black civilians. Until the election of Donald Trump, who made his “Blue Lives Matter” commitments well-known from the very moment he announced his candidacy, popular demonstrations against police killings spread like prairie fires across the country from Oakland to Ferguson, Missouri, and on to Baltimore, Chicago, Dallas, and Baton Rouge. As a rallying cry, Black Lives Matter opened up public space for disparate campaigns, networks of grieving families, criminal justice reform organizations, and localized struggles against the carceral state that had been in motion for decades. At the same time, however, like most great slogans, #BlackLivesMatter advanced a rather straightforward, if not simplistic analysis of the issue at hand, that the problems of policing were primarily racial. Black Lives Matter fervor also unleashed a torrent of historical misinformation, conspiracy theory, and wrong-headed thinking about politics. In elevating a race-centric interpretation of American life and history, Black Lives Matter has actually had the effect of making it more difficult to think critically and honestly about black life as it exists, in all of its complexity and contradictions. Rather than clearing a path through the thickets, some left intellectuals have made peace with this overgrowth of bad historical thinking, even though it threatens to choke out the possibility for cultivating the kind of critical left analyses of society we so desperately need.

Over the last five years, Black Lives Matter has served as a broad banner uniting citizens from all walks of life against the most egregious and visible use of police force against black civilians. Until the election of Donald Trump, who made his “Blue Lives Matter” commitments well-known from the very moment he announced his candidacy, popular demonstrations against police killings spread like prairie fires across the country from Oakland to Ferguson, Missouri, and on to Baltimore, Chicago, Dallas, and Baton Rouge. As a rallying cry, Black Lives Matter opened up public space for disparate campaigns, networks of grieving families, criminal justice reform organizations, and localized struggles against the carceral state that had been in motion for decades. At the same time, however, like most great slogans, #BlackLivesMatter advanced a rather straightforward, if not simplistic analysis of the issue at hand, that the problems of policing were primarily racial. Black Lives Matter fervor also unleashed a torrent of historical misinformation, conspiracy theory, and wrong-headed thinking about politics. In elevating a race-centric interpretation of American life and history, Black Lives Matter has actually had the effect of making it more difficult to think critically and honestly about black life as it exists, in all of its complexity and contradictions. Rather than clearing a path through the thickets, some left intellectuals have made peace with this overgrowth of bad historical thinking, even though it threatens to choke out the possibility for cultivating the kind of critical left analyses of society we so desperately need.

Mia White’s “In Defense of Black Sentiment,” offers criticism of my 2017 Catalyst essay, “The Panthers Can’t Save Us Now: Anti-Policing Struggles and the Limits of Black Power,” and Kim Moody’s “Cedric Johnson and the Other Sixties’ Nostalgia” addresses that essay, and my more recent New Politics essay, “Who’s Afraid of Left Populism?” I appreciate that both White and Moody have taken time to craft responses to my work. I first came to know White as part of a growing, dedicated community of scholars researching the 2005 Hurricane Katrina disaster and the long process of reconstruction and recovery that followed. White’s work stood out because of its focus on the Mississippi Gulf Coast, often neglected by the urban-studies bias towards the plight of New Orleans. I’ve never met Moody, but during the aughts, when my economist colleague Chris Gunn and I routinely co-taught a labor course at Hobart and William Smith Colleges, Moody’s writings on American working-class history were instrumental in shaping our approach to the course, and were a mainstay of our assigned readings. His 1997 book Workers in a Lean World was especially helpful for making sense of the painful impact of globalized production on the once-bustling manufacturing towns surrounding us in Western New York. While I think we are all on the same side politically, and there are definite points of agreement between our essays, White and Moody rehearse some errant arguments about race, politics, and class power that have become orthodoxy on the contemporary Left. In what follows, I want to contest some of their core claims regarding the character of black political life, the role of contemporary policing in managing surplus population, New Deal social democracy, and African American progress, and finally, the relationship between electoral politics, the Democratic Party, and the future of the American Left.

Both authors abide some version of Black Lives Matter sensibility, sharing a suspicion of class-conscious politics as always reproducing racial disparities historically and into the future. My central contention with both White and Moody lies in their reluctance to engage in meaningful class analysis of black political life. Their use of clichés and anachronisms when addressing black life reflects a broader affliction of the contemporary Left. This difficulty in discussing black life in a critical-historical manner filters out and contaminates interpretations of labor and capital, and ultimately undermines strategic political thinking. At the start of his essay, Moody says that he “will not attempt to present a different analysis of ‘black exceptionalism’,” but in fact, his and White’s essays are both defenses of black exceptionalism, the very interpretative and discursive sensibility that I have criticized in recent writings. Black political life is and always has been heterogeneous, a complex of shifting ideological positions and competing interests. Black political life has always been shaped by broader conflicts between labor and capital, even in the contexts where black non-citizen or second-class citizen status was the norm. When White and Moody turn to black political life, however, these basic empirical-historical facts of African American political development are minimized, or vanish altogether. This is not a new problem.

Black Life Beyond the Barricades

In his 1962 essay, “Revolutionary Nationalism and the Afro-American,” Harold Cruse complained “American Marxists cannot ‘see’ the Negro at all unless he is storming the barricades, either in the present or in history.”[1] The World War II veteran and ex-Communist partisan put the matter even more bluntly saying that American Marxists—his euphemism for his former party comrades—wrongly view blacks as “a people without classes or differing class interests.” Cruse also denounced the falsehood of the “Negro Liberation Movement” a favored term of his left contemporaries, as an “’all-class’ affair united around a program of civil and political equality . . .”[2] I don’t evoke Cruse here because I think he had all the answers to what ails us—the same is true for my discussion of Bayard Rustin below. Cruse is frustrated by the oversimplifications and occlusions of African-American life and history he has witnessed within the Communist Party. From this acknowledgement of a more complex, class-stratified world beyond the desks of Herbert Aptheker and his old CP comrades, Cruse pivots towards a defense of a revolutionary black leadership. What he desires is that the black bourgeoisie act as a truly national bourgeoisie. Setting aside the problems of this argument, which Cruse would enlarge in his 1967 book The Crisis of the Negro Intellectual, his basic criticism of the Left may be as insightful today as it was when he first wrote it.

In the age of Black Lives Matter protests, many activists and academics seem unable to see the complexity of black life beyond the barricades, or outside the frame of the latest viral video killing of a black civilian. Neither White nor Moody engage in much substantive discussion of actually-existing black political life, the fact of differing black class interests, and the fundamental demographic and cultural changes within black life and American society of the last half century. While White attempts to marshal normative theory and autoethnography to build a case for a redemptive black power sensibility, Moody either explains away class conflict among blacks as inconsequential, or assumes the familiar, deferential posture of white New Leftists towards the “self organization of the oppressed.” In both cases, their prose remains lodged in the literary conventions emerging from decades-gone social conditions. White’s essay rehearses black power sentiment, the black population as a socially coherent and unified political constituency deriving from twentieth century conditions of black ghettoization and Jim Crow segregation. Moody’s essay, on the other hand, recalls New Left anxieties and attempts to navigate the spatial and cultural gulf between the middle-twentieth century urban black ghetto and the expanding white suburban middle class and its deepening commitments to capitalism.

White employs the racial “we,” to drive her analysis, and throughout she engages in a form of ventriloquism that has long been a problem within black political life and scholarly and popular interpretations thereof. “We are still where we are, surveilled and killed while walking, breathing, doing our jobs, leaving a vacation, visiting friends, or driving a car,” White writes, “Thus, to ask Black readers to shrug off race as a central analytic is to ask them to 1) do what they already do on a regular basis to survive as good liberal subjects as if they don’t, and 2) pretend that the very reason survival is so fraught has nothing to do with the same reason we are ignored as an electorate.”[3] Aside from how the second half of her statement mischaracterizes the intent and conclusions of my argument, there are two immediate problems with this passage. First, while her use of the first-person plural has dramatic impact, it obscures the actual dynamics of police killings, advancing the falsehood that all blacks regardless of class position are equally likely to be victims of daily surveillance, harassment, detainment, and arrest. White abides the popular New Jim Crow accounting of the carceral state as fundamentally racist in motives and effects, but this is hyperbolic and misleading. Blacks are disproportionately represented among the victims of arrest-related incidents in most years since the start of this century, but blacks are not the majority of victims. As I argued in the 2017 Catalyst essay and recent New Politics essay, contemporary policing has a class character that is not reflected in viral videos, which only capture some police-civilian conflicts and are circulated through social media networks and practices that are governed by standing assumptions and ideological predispositions of users and their social and psychological needs, often at the expense of other evidence like national Justice department statistics, killings undocumented by cell phone cameras, and deaths that do not conform to the New Jim Crow frame. The blackness of the victims is visible, evocative, and foregrounded in popular understandings of why they were targeted, their common position among the most submerged elements of the working class is not as readily legible for some audiences.

Second, this use of the racial “we” preempts politics, and by that I am not simply referring to the arena of elections and party politics as White implies, but the broader contexts where social power is mobilized and contested. The very real diversity of black experiences and political sentiments of the carceral state are lost in White’s essay, and in much Black Lives Matter discourse, both of which retreat into abstraction. In other words, black people do not merely interface with police departments as suspects and offenders, but also as crime victims, lawyers, witnesses, public defenders, social workers, judges, corrections officers, probation officers, beat cops, city administrators, and wardens, especially in cities like Baltimore, Washington, D.C., Chicago, and others with sizable black populations. White’s defense of black sentiment, against my critique, forces these differences out of view, and gives the impression that all blacks, “we” view the problems of crime and punishment in the same ways, and are ready to prioritize the same raft of solutions. In fact, she concludes, “the well-being of Blacks always also requires—as a means to attend to accumulating, historical, unfair disadvantage—a collective sense of Black self-determination.” This view that the black population constitutes a cohesive political constituency with commonly held interests was not true during the Jim Crow era, and it is certainly not a useful way of thinking about black political life now.

Black life was complex under Jim Crow segregation, albeit cramped by de jure and social constraints imposed on black political will in the North and South. Black political life was and is animated by competing interests and different visions of what society should be. Such dynamics took on a unique character in different epochs given the broad experience of slavery and Jim Crow segregation, but the fact of non-citizen or second-class citizenship status did not generate a unified set of aspirations and interests among blacks, even if some projected the sense of common black passions and strivings to suit their particular interests as black leaders (or scholars), white benefactors, or white supremacists.

The black population has experienced profound demographic and political changes since the fifties. Poverty has decreased since the landmark 1954 Brown v. Board of Education decision, which overturned the “separate but equal” precedent on which the Jim Crow edifice stood, from the plight of the vast majority of blacks to the experience of roughly a quarter of the black population. The black middle class expanded after World War II, and black integration into mass culture as consumers and producers, integration in higher education, employment, corporations, the non-profit world, and public sector employment was spurred by omnibus civil rights legislation as well as opportunities provided by New Deal, Fair Deal, and Great Society programs. In many locales black governance became a reality. By the late 1980s, the three largest American cities elected black mayors, and by then, the presence of black mayors and black-city council majorities were the norm wherever there was a sizable black electorate. These changes were the consequence of popular pressure and the public policy it produced, the initiatives of the New Deal Democratic coalition and the Johnson White House. Somehow in our contemporary moment, the New Deal coalition has been recast as the villains of history. However, that narrative, now orthodox among many on the Left, silences the actually existing historical voices and experiences of blacks who benefited from, supported, and fought to expand the policies of the New Deal, Fair Deal, and Great Society periods. Even worse still, this narrative breeds cynicism, leaving us with a wrong-headed view of the political process, and what the Left might do now, under very different social and political conditions, to abolish poverty, decommodify housing, health care, transportation, education, and other basic needs, and expand popular democratic power within the economic realm—all of which, like the eradication of police brutality would disproportionately—though not solely—benefit black citizens. It does not take much thought to conclude that the form of social democracy produced by the New Deal coalition was limited, especially compared to other industrialized nations, but it takes a particular type of bad faith to conclude that the horizon of contemporary left aspirations should be limited by the history of the New Deal.

The sheer size of the black population today should in and of itself render such talk of “black self-organization” and “black sentiment” obsolete. At nearly 46 million, the black population in the US is greater than the population of Canada, three times the size of the population of Greece, and slightly larger than the combined population of Oceania (i.e., Australasia, Melanesia, Polynesia, and Micronesia). Why are so many incapable of thinking about the black population with the same complexity they would afford those populations? To his credit, Moody does briefly acknowledge the fact of different class interests among blacks, but he does not provide the kind of historical-materialist analysis that you might expect from someone who has dedicated most of his adult life to the study of class struggle. Despite his posturing about the “right to black self-organization” it is interesting that when Moody encounters such self-activity in all of its contradictory, historical motion, he has difficulty realizing its import. Rather than a full-bodied class analysis of black political life, his claims instead resemble the more familiar culturalist arguments of class from the Black Power lectern. In other words, all the black elites are either dupes or sell-outs, the black working class and poor are victims, and somewhere, lurking around the historical corner is the revolutionary black subject waiting to be born.

Moody recognizes the “contradictory and even reactionary role” of black elites in shaping punishment policy, only to shrug off their influence, concluding they played “most certainly a subordinate role in terms of federal and state policy and practice.”[4] Here Moody mischaracterizes the actual dynamics of the carceral build-up, a process that took place largely at the local and state level, the very contexts where black political power and mobilization mattered. The role of black public officials within the contexts of cities like Washington, D.C., Detroit, New Orleans, and elsewhere was anything but subordinate. Subordinate to whom? Moody misses the very powerful role that these black elites played, and continue to play in formal party politics and local economic growth regimes, in legitimating neoliberalization and, at times, insulating such forces from criticism even when they embark on policy decisions that will have negative social consequences for black constituencies. More troubling, Moody diminishes the role that various black constituencies, neighborhood groups, landlords, business owners, clergy, educators, and activists, not simply political elites, played in shaping the carceral expansion. The sense of different subject positions among blacks, which cannot be reduced simply to the “petty bourgeoisie” and the “long struggle for black freedom” as Moody does, is totally lost. Moody refers to the demands of working-class blacks for more police protection and tougher crime policy, but in a manner that returns quickly to the victim narrative, disconnecting their conscious actions as citizens from their unintended consequence, mass incarceration. James Forman, Jr., Michael Javen Fortner, and Donna Murch among others have provided a more useful sense of how these processes unfolded in real time and space, and the different motives that animated distinct black political choices.[5] There were liberal and progressive blacks and whites in Washington, D.C. who supported decriminalization of marijuana and a handgun ban, and black nationalist community activists who opposed both measures. We would never know these details that if we adhere to Moody’s generalizations about black life. More importantly, black opposition to both of those measures, policies which most urban dwellers would champion as progressive today, actually mattered. The legislation was defeated, marijuana arrests over the next few decades contributed mightily to the carceral expansion, and the proliferation of handguns made the District of Columbia one of the most dangerous cities in the U.S.

As my comrade Adolph Reed, Jr. has cautioned, “taxonomy is not critique.” Merely addressing the alleged excesses and missteps of black elites, without much concern for what class means in daily lives, organizational contexts and real political fights, cannot stand in for serious analysis of how black life is organized in myriad ways, like that of all other Americans, by the processes of production and realization of surplus value. A first basic step in a critical-left analysis is acknowledging the actual forces at play within black political life, rather than falling back on Black Power rhetorical formulas. These problems in Moody’s essay come into even sharper relief when he attempts to defend the liberal racial justice frame.

Policing Surplus Population

“This is my eleventh year of being shoveled into every major prison in the most populous state in the nation, and the largest prison system in the world . . . Hidden are the facts that, at each institution I’ve been in, 30 to sometimes 40 percent of those held are black, and every one of the many thousands I’ve encountered was from the working or lumpenproletariat class.”

George Jackson, Blood in My Eye (1972)

The argument that contemporary policing in the United States is fundamentally about managing relative surplus population has been advanced by neo-Marxist and socialist thinkers over the last fifty years from George Jackson’s prison writings to Stuart Hall et al.’s Policing the Crisis, and Ruth Gilmore’s Golden Gulag among others. [6] Although they do not employ a Marxist analytical framework, other critical social scientists have drawn similar conclusions regarding the class character of mass incarceration. Loïc Wacquant’s notions of the hyperghetto and hyperincarceration focus on submerged segments of the black urban population who are most heavily targeted by police and most likely to be incarcerated.[7] In a similar vein, Brett Story critically engages the concept of the “million dollar block,” which denotes the spatially concentrated origins of the nation’s 2.3 million prisoners in a handful of dense urban neighborhoods that are the target of massive state investments in policing and incarceration. [8] All of the aforementioned works acknowledge very visible racial inequalities, and begin from a basic sense of racial justice as a cherished political value. What they also share, however, is a more discerning interpretation of which portions of the black population have borne the brunt of the carceral expansion, and what those segments share with similarly-situated prisoners, parolees, and ex-offenders across ethnic and racial groups.

Thinking about mass incarceration in terms of surplus population helps us to name precisely those who are most regularly surveilled and harassed by police, and who are the most likely to have their livelihoods as ex-offenders determined by the long reach of the carceral state. Unlike the New Jim Crow framing, discussing relative surplus population focuses our attention on which portions of the black population are most likely to be subject to intensive surveillance and policing. Although many blacks experience racial profiling in policing practices and in retail consumer contexts, class is a much more powerful determinant of who is actually arrested, assigned a public defender, convicted, sentenced, and incarcerated. Moody notes that the carceral state is “very selective of which white people are most likely to be arrested, tried and incarcerated.” These same selective dynamics, however, are at play across other U.S. populations including African Americans. Blacks are disproportionately represented among those who are arrested, convicted, incarcerated, and under court supervision because blacks are still disproportionately represented among the nation’s poor. Hence, if poor neighborhoods and communities are overpoliced, then it is no wonder as Moody notes that “blacks are almost six times and Latinos three times more likely to be sentenced to ‘hard time’ in prison than whites.” I have never denied these racial disparities, but what I have argued instead is that these racial disparities regarding policing and incarceration mirror the demography of the most vulnerable segments of the working class. Moody pins the disproportionate sentencing of blacks and Latinos to prison time compared to whites on discrimination, but without much consideration of other underlying dynamics. Namely, he neglects how poverty and the compulsory use of underfunded and overextended public defender’s offices produce the kinds of disproportionality in conviction rates across race. What appears as racial disparity is underneath it all, a function of class power and dispossession. By focusing on the broader problem of relative surplus population, we might well connect these discussions of mass incarceration to the broader problems of capitalist society, as well as make common cause with the millions of overpoliced Americans who do not fit into a Black Lives Matter framework. In other words, the problem of mass incarceration as we know it is not an aberration, but rather a constitutive part of governing in the aftermath of welfare state liberalism.

In an odd interpretative move for a veteran labor historian, Moody seizes on employment status at the time of arrest as though that moment tells us all we need to know about the lives of this segment of the working class. Moody offers a rather selective reading of incarceration statistics, one guided by an understanding of class that seems closer to behavioralist social science than historical materialism. He contends that those who are sentenced to prison are not primarily drawn from the surplus population. To evidence this point he refers to a study by the National Center for Education Statistics, although the full citation for this study is not provided. Moody reports “nearly two-thirds of the prison population were employed prior to incarceration. 49% of all prisoners were employed full-time and another 16% in part-time work before entering prison, while another 8% were students, retired, or permanently disabled.”[9] Moody then notes “only 19% of prisoners in 2014 were unemployed at the time of incarceration.”

The statistics that Moody attributes to the National Center for Education Statistics were drawn from a 2014 survey conducted by the Program for International Assessment of Adult Competencies, a research initiative of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development that assesses literacy and skill levels for workforce development. That survey was taken between February and June 2014 and included 1,315 inmates—1,048 males and 267 females. I am not sure why Moody chose this data when there are other sources that provide decidedly fuller and more rigorous portraits of the pre-arrest experiences of those who are incarcerated.[10] I am also not as confident as Moody that we can make useful generalizations from this sample, one that was drawn from a selection of prisons. This is especially a concern regarding any conclusions about women, who constitute a fast-growing incarcerated population. Most importantly, we should not make historical generalizations about carceral dynamics that have taken shape slowly and unevenly across the country over the last half-century based on one year’s worth of data, no matter how fulsome it might be. Like so much analysis in this vein, complexity and context, be it within black political life or in the differing policies of states ranging from Louisiana to Minnesota, seem to fall away in favor of easy moralism. Still, there are bigger interpretive problems here with both this particular use of employment statistics to discuss class, and his sense of the argument we have made regarding relative surplus population and policing.

As Moody well knows, class is not merely a matter of employment or income, but rather it is more fundamentally about the social relations of production. The relative surplus population, or reserve army as Marx developed the concept, cannot be reduced to latter-day metrics of unemployment. Class is set in historical motion, and the reserve army represents a relative, contingent condition of the working class, rather than an ascriptive status. Marx denoted four fluid layers of the reserve army, a floating reserve of the temporarily employed, a latent segment made up of those not actively looking for work, but who may be mobilized to meet capital’s shifting valorization requirements, a stagnant portion of those with “extremely irregular” employment, and lastly, the sphere of pauperism, which is the “hospital of active labor-army and the dead weight of the industrial reserve army.”[11] These populations are not fixed, but rather their composition is expanding and contracting relative to the dictates of capital’s need for living labor.

Employment status at the time of arrest is only part of the story in the lives of those governed through incarceration. For too many, it is after their sentence has been served that the real work of management of surplus population begins. The prospects of gainful employment for ex-offenders is greatly diminished by the combined force of the social stigma and discrimination they face, mandatory conviction self-reporting on job and college admissions applications, and the denial of access to public relief, unemployment insurance, and housing assistance in some states.[12] Ex-offenders are also compelled to take low-wage work to meet the requirements and avoid punishment under an elaborate, manipulative probation system.[13] In their empirically-rich study of the ex-offender employability crisis, Jamie Peck and Nick Theodore focused on Chicago’s majority-black, west side neighborhoods of North Lawndale, East and West Garfield Park, and Austin, which are home to the highest concentrations of returning ex-offenders in the nation. They conclude that upon returning home to Chicago ex-offenders face a “profoundly inhospitable labor market.”[14] Moreover, Peck and Theodore contend “the prison system has become a labor market institution of considerable significance . . . configuring prevailing definitions of employability, shaping the social distribution of work and wages, prefiguring the terms under which different segments of the contingent labor supply enter the job market, and shaping their relative bargaining power.”[15] A growing swell of policy activism has been dedicated to toppling these barriers to economic mobility facing formerly incarcerated persons. Such political efforts have bore some fruit in recent years, with many states passing “ban the box” legislation, ending mandatory self-reporting of prior convictions on job applications and college admissions, but critics rightly argue these policies do not go far enough to eliminate discrimination against ex-offenders. The fact remains that the carceral state contributes greatly to the reproduction of the industrial reserve, and in a manner that is intimately connected to the postindustrial urban economies.

Moody lifts my discussion of policing surplus population out of the context of the gentrifying city, missing the ways that aggressive policing is central to urban real-estate development and the tourism-entertainment sector growth, both of which serve as central economic drivers in the contemporary landscape. Moody seems to forget that since the late eighties and the accelerated, broad adoption of zero-tolerance strategies, the overwhelming resources of contemporary policing are dedicated to the routine surveillance, targeting, arrest, and prosecution of those whose activities are a means of basic survival and who are only nominally or infrequently employed in the formal wage economy. Much of routine policing activity is focused on regulating criminalized forms of work—pan-handling, busking, sex work, the drug trade, property crime, operating as an unlicensed vendor, the illegal trade in stolen merchandise, and to be frank, robbery, and mugging, keeping in mind that slightly more than half of the incarcerated were convicted of violent offenses. There is also ample evidence that such deployments of more aggressive policing tactics are meted out in explicitly segregative ways that maintain the class order, insuring perpetual accumulation on one hand by defending middle-class and affluent consumer spaces, tourism districts, office parks, and gentrifying neighborhoods, and on the other, regulating the poor, homeless, so-called “disconnected youth,” non-citizen workers, and criminalized forms of work.[16]

Finally, Moody’s defense of the New Jim Crow sensibility neglects recent and well-publicized trends in carceral demography, changes that further erode the claim that the carceral expansion of the last four decades was primarily driven by racial disparity in anti-drug policy. Between 2000 and 2015, the black male incarceration rate dropped by more than 24 percent, while rates for white men climbed slightly.[17] During the same period, the incarceration rate for black women declined by nearly 50 percent, while the inverse was true for white women, who experienced a 53 percent increase. This is progress on the racial justice front, perhaps a consequence of the sharpening public debate and intensity of local and state-level organizing. Yet at the same time, such changes are a reminder that the carceral state’s underlying motives are not fully captured in slogans like the “New Jim Crow” or “Black Lives Matter.” A dogged fixation on racial disparities only provides a narrow window on the carceral crisis. That is a window that we are familiar with, it connects rather easily to liberal interpretations of American society and organizing strategies that survived the Cold War, while other modes of working-class analysis and social action were criminalized and eviscerated. Shifting our attention to the problem of relative surplus population allows us to see the connections between the plight of black teenagers from Chicago’s “wild hundreds” arrested for their part in a “flash mob” robbery of a Magnificent Mile clothing store, and that of a white middle-aged mother, her son and his live-in girlfriend who are arrested for selling oxycontin in their small town in Southern Missouri. Marxist analyses of mass incarceration should be able to account for such situated experiences of the working class in the post-Fordist economy.

Mythologizing the New Deal

White and Moody advance and enlarge popular fictions about New Deal social democracy and its racial limitations that have become new orthodoxies on the American Left. And true to form, their attempts to root out the limitations of the New Deal silence black citizens’ historical responses to New Deal policy, reflected in part by the large-scale migration of black voters into the Democratic Party ranks from the Depression onwards. “The benefits of universal programs such as the New Deal,” White declares, “cannot be misremembered as materially transforming for the better the lives of the most marginalized Black Americans.”

White contends, “the New Deal is widely critiqued for failing Black people, specifically because most New Deal Programs discriminated against Blacks, authorized separate and lower pay scales for Blacks, refused outright to support Black Applicants (for example the Federal Housing Authority refused to guarantee mortgages for Blacks who tried to buy in white neighborhoods), and the Civilian Conservation Corps maintained segregated camps.” She then turns to the familiar claim that the farm and domestic worker exemptions of the 1935 Social Security Act are irrefutable evidence of the racist limitations of the New Deal policy legacy.[18] This is a falsehood repeated so many times that it is now widely accepted as true.

While Southern Democrats certainly sought to exclude black workers from protections, as historian Touré Reed argues; however, “the most obvious problem with the claim is that it ignores the fact that the majority of sharecroppers, tenant farmers, mixed farm laborers and domestic workers in the early 1930s were white.”[19] Some 11. 4 million whites were employed as agricultural laborers and domestics compared to 3.5 million blacks. As such, Reed reminds us, the Social Security exemptions excluded 27 percent of all white workers nationally. As an historical explanation of the New Deal’s limitations, the Jim-Crowing of national social policy thesis does not hold up nor is it based in the preponderance of actual research by historians themselves. Rather, the power of particular capitalist blocs prevailed, in this case the landed interests represented by the Farm Bureau, insuring the vulnerability of the most submerged and dispossessed workers.

This New Deal mythology also wipes clean the record of black support and influence over the subsequent trajectory of Roosevelt era reforms, and those pursued after the Second World War. There is little mention in their account of the massive public works programs that employed thousands of blacks, namely the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCCs) or the Works Progress Administration (WPA). [20] These public works projects were publicly funded and publicly managed, employing millions of Americans from all walks of life. The CCC workers built roads and bridges, refurbished portions of the Appalachian Trail, and developed numerous public amenities of the US parks service.

There was no doubt discrimination in the CCC program. Black enrollment was capped at ten percent of total enrollment, which mirrored the black proportion of the national population. As Nick Taylor points out, this level of CCC employment did not meet the high demand for relief among African-Americans who were especially hard hit by the Depression. White nevertheless overreaches in claiming that all CCCs were segregated. In the Deep South CCC camps were segregated, sadly in conformity with the Jim Crow order, but beyond the Mason-Dixon line, many CCC work camps were integrated. All told, between 1933-1941, some 250,000 blacks were enrolled in the Corps. Luther Wandall summed up his experience in the CCC this way in the pages of Crisis Magazine: “On the whole, I was gratified rather than disappointed with the CCC. I had expected the worst. Of course, it reflects, to some extent, all the practices and prejudices of the U. S. Army. But as a job and an experience, for a man who has no work, I can heartily recommend it.”[21] Wandall’s comments, which are unsentimental and critical, and the scores of similar testimonies by other black men and boys who joined the CCC camps, should caution us against interpreting the meaning of New Deal social policies for its historical constituencies against the din of contemporary debates and preoccupations. There is a parallel dissonance between the actual experience of the G.I. Bill’s educational and training provisions by black servicemen nationally, and contemporary efforts to impugn the policy as evidence of meta-historical white supremacy. [22]

In the case of the WPA, it undertook a range of projects that provided work and income to millions of Americans, who were employed in the construction of public buildings, public art, music and theater projects, literacy programs, and the development of tourist guides for every state in the union. In 1935, blacks constituted around 15% of the WPA workforce, some 350,000, at least in raw numbers disproportionately benefiting from the program vis-à-vis whites. Ironically enough, many black writers who are now canonized by contemporary anti-racist liberals, writers like Dorothy West, Richard Wright, Margaret Walker, and Zora Neale Hurston to name a few, were employed through the Federal Writers Project. Likewise, one significant but forgotten achievement of the WPA was the oral history project undertaken by John Lomax and Sterling Brown that collected the stories of hundreds of antebellum slavery’s survivors, by then in their eighties and nineties, providing us with a priceless audio archive of their perspectives on bondage and freedom. These clearly anti-racist dimensions of the New Deal are buried underneath convenient and often errant readings of the motives behind certain policies, their implications for black citizens and the actual responses from black publics who lived and worked in the context.

It should be noted as well, that thousands of black workers were unionized in the steel mills, automotive plants, packinghouses, and ports across the U.S. during the Depression, World War II, and after because of the right to collective bargaining under the Wagner Act.[23] The wages they earned in these industries, and in many cases their unions themselves became the key economic bulwark of the later Civil Rights Movement.

More evidence of the complex relationship between black popular struggles and the Roosevelt administration can be seen in the passage of Executive Order 8802. This measure desegregated the defense industries drawing thousands of blacks into the wartime workforce and was signed under the threat of a national protest, the original “March on Washington” movement organized by black trade unionist A. Philip Randolph. [24]

In attempting to characterize it as a type of “identity politics,” Moody misreads the context of A. Philip Randolph’s leadership of the original March on Washington Movement. Moody contends that Randolph and Rustin were committed to black self-organization, but this is a rather superficial and anachronistic reading of the historical moment and the choices Randolph made in his attempt to desegregate the defense industries. Moody refers to Randolph rather dismissively as a “self-proclaimed socialist” before claiming that the planned March on Washington, and later formations such as the Negro American Labor Council represent commitments to “identity politics” before the term came into existence. “Was this ‘identity politics’ without the label?,” Moody asks, “Or was it the recognition that in the struggle for black freedom and equality black self-organization was an indispensable tool even (or perhaps particularly) where unity and solidarity with whites was expected as in the labor movement but often denied?” The simple answer is no, it was not identity politics. Randolph was clear in his opposition to the most nationalistic styles of politics among blacks, as evidenced in his vocal support for the “Garvey must go” campaign. Moody’s reliance on the white New Left and more contemporary radical fetish of black self-organization also gets in the way of useful interpretation of this moment. Of course, Randolph demanded full black participation, and crisscrossed the nation to stoke black citizen commitments, precisely because the black population was an expanding bloc of the Democratic Party coalition. It was the New Deal after all that began the process of black exodus from the Party of Lincoln. Somehow, Moody glosses this important fact of national political context and why it would be important for Randolph and his allies to prepare for a strong show of force of the emerging black electorate. For the record, whether the Left should acknowledge black self-organization or not is someone else’s battle, one with origins in the white New Left’s nearly pathological search for political relevancy and authentic revolutionary subjecthood as they stood uneasily between concomitant black political struggles in the fifties and sixties, and the growing social conservatism that accompanied the expansion of the mostly white, suburban middle class.

Public works projects, black workers participation in union struggles, and the desegregation of the defense industries altered public perceptions about race and gender equality, brought Americans from different backgrounds into real and often unprecedented contact with one another, and presaged the expansion and new assertiveness of civil rights campaigns after the war. These reforms also meant real, tangible improvements in the lives of millions of African Americans and so frequently provided the material context in which they could more easily participate in Civil Rights struggles. Rather than seeing the era of New Deal reform as a great exception, and as yet another episode where American politics is hemmed in by the “original sin” of race, we should situate the era more firmly within domestic and international class struggle, the historic effort of the US capitalist class to save the system from its own contradictions amid the Depression, and the countervailing movement of popular and labor forces to impose a more just order.[25] This was exceptional in the sense that it marked a period when capital was forced to take responsibility for the costs of social reproduction of labor, a function it has abandoned with far-reaching and disruptive social consequences under decades of neoliberalization, the dismantling of the welfare state apparatus, and the privatization of formerly public goods and services.

As they have migrated from the scholarly studies of Ira Katznelson, Jefferson Cowie, and others to the popular renditions of Ta-Nehisi Coates, and into the realm of Left common sense, the “New Deal was racist” narrative has often conflated the Depression-era New Deal policies with work of the New Deal Democratic coalition after the Second World War. In the process, such accounts run together and roundly condemn policies that were produced through distinct geo-political contexts, characterized by a shifting balance of class forces, changing partisan and Congressional leadership, and different strategic logics. The first and second New Deal enacted under Franklin Roosevelt reflected the growing power of organized labor, and concessions made by capital for the assurance of continued social stability and uninterrupted compound growth. The Fair Deal enacted after the war under the leadership of Harry Truman set in a motion a commercial Keynesian transformation of urban society through the 1949 Housing Act. The expansion of federally-backed mortgage lending, massive investments in urban renewal and inner-city public housing construction shifted away from the state-funded and state-managed public works of the Depression creating a bonanza for real-estate capital, local construction trades, architectural firms, and manufacturers of industrial building materials. If there is a policy initiative of the New Deal coalition that should be roundly condemned it is this 1949 measure that entrenched racial and class inequalities into a new metropolitan spatial order. The sixties saw efforts of New Deal Democrats to rectify these inequalities, again an important historical detail that is obliterated in the sweeping brush strokes of the “constraint of race” narrative. The result was a wave of national anti-racist and anti-poverty legislation that produced major social progress, but inasmuch as Great Society legislation avoided direct, aggressive market interventions, such measures failed to create the same structures of employment for the black urban poor that had been produced over time for many whites through public works, defense contracting and industrialization, and the right to collective bargaining.[26]

Why Rustin Still Matters

Both White and Moody attempt to cast doubt on the prospects of universal public policy in our times. They both abide the “constraint of race” thesis, that is that any and all attempts to create social policy that might benefit the greatest number of Americans will ultimately fail because of racism, or in a slightly different iteration, universal public policies will only retrench existing racial disparities of wealth, income, health care, housing, and education.

Moody concludes that my politics are afflicted by nostalgia for the realignment theory touted by Rustin and Michael Harrington. Mind you, he extrapolates this claim from a passing reference to Rustin in my 2017 Catalyst essay, where I briefly criticize Rustin’s turn to “politics of insider negotiation” before touting the merits of the 1966 Freedom Budget for All Americans he co-authored with Randolph, and lamenting its being eclipsed by Cold War liberals’ rather narrow focus on institutional racism and the alleged cultural pathologies of the poor. Somehow, Moody interprets my embrace of that agenda with a wholesale acceptance of Rustin’s increasingly conservative commitments to the Democratic Party. In the process, he misreads both Rustin’s politics and mine.

I have criticized Rustin’s conservative turn in various places, characterizing him as a tragic figure in my 2007 book, Revolutionaries to Race Leaders, and that argument largely channeled Stephen Steinberg’s analysis which appeared here in New Politics a decade earlier.[27] Moody doesn’t attempt to contextualize and explain Rustin’s increasing conservatism, so I will here. It is no secret now that Rustin was a marginalized figure during the early stages of the postwar civil rights movement, he was forced to play an offstage role, serving as a mentor to Martin Luther King and a key strategist in various demonstrations that would prove pivotal to the growing movement to topple Jim Crow. He was held at bay by clergy because of his gay sexuality and youthful Communist commitments, which made him an easy target for segregationists, the FBI, and other foes of racial progress looking to derail the southern campaigns. After having been closeted within the leadership circles of the postwar movement for years, Rustin finally found himself taking on a more public role as broker between the movement and the Kennedy White House. He justifies his choice of insider-negotiation over popular protests in his 1965 Commentary essay, but in the process Rustin wrongly confines popular struggles to an expired stage in black political development.

Rustin’s problem was two-fold. He simply misread his times, and perhaps more fatally, he jettisoned mass mobilization and civil disobedience, which had been fundamental to the postwar civil rights movement, in favor of brokerage politics with the Democratic Party. He thought the passage of major civil rights legislation was the beginning of a new political stage, one that would make it possible to push for deeper, broader social reforms exclusively through the formal democratic process. As I said in 2015, in an extended interview with UIC graduate student Gregor Baszak, “I doubt Rustin’s wisdom at that historical moment. His belief that participation sans protest could steer the Democratic Party during the middle 60s towards more extensive commitments to social democracy seems even more foolhardy in hindsight. He had reason to be optimistic about the prospects given the Johnson administration’s civil rights reforms and the War on Poverty, but there were very real reactionary tendencies within the Democratic Party at that time. The party included Vietnam hawks, Southern segregationists, and legions of voters who were firmly committed to the middle-class consumer society. Rustin cedes too much ground to them. And, again, his fatal flaw is that he no longer seems to appreciate the role of movement pressure.”[28] Hence, Rustin surrendered the repertoire of movement strategies that might have enabled African Americans and other more progressive elements in American society to press for more substantial policy reforms, such as those contained in the 1966 Freedom Budget.

Despite his strategic missteps and rightward drift, Rustin’s criticisms of black separatism and black power militancy remain relevant in this tide of Black Lives Matter. His claim, cited by Moody, that the “future of the Negro struggle depends on whether the contradictions of this society can be resolved by a coalition of progressive forces which becomes the effective political majority in the United States” remains powerful, and unfulfilled. Rustin was clear, and we should be as well, that every major political advance of blacks in US history was not merely the outcome of “self-organization” of the oppressed, but rather the result of a diverse cast of political actors. The abolition of slavery, the short-lived advances of Federal Reconstruction, the discrete gains of blacks during the Roosevelt administration, and the toppling of the Jim Crow system were achieved through the self-activity of some blacks, the principled commitment of non-blacks to historically concrete forms of social justice, and the begrudging acceptance of still others that the status quo, whether slavery or Jim Crow, was no longer sustainable.

In slightly different ways, White and Moody both characterize me as some sort of Democratic loyalist who sees the future of blacks or the laboring classes more generally in closing ranks with the Democratic party. In an odd conclusion, Moody claims that the Sanders wave and surging interest in class analysis and socialism, especially among millennials, may in fact lead to a mass migration of the Left into the Democratic Party ranks. “With this renewed hope,” Moody writes, “has come a demotion of race as a subject of socio-economic analysis in the name of class that is, in reality, a return to America’s quintessential business-funded, neoliberal-dominated, undemocratic, cross-class social construction: the Democratic Party.” White reaches a similar conclusion, “whereas the pivot to support class political interests along party lines with the kind of power and influence Johnson seeks has not demonstrated to Black Americans the kind of mutuality and support required in an ongoing, historically and cumulatively race-class reality.” They both fear that emphasizing a class-conscious politics, and organizing around commonly-felt needs, that is, those basic necessities that we all require for reproduction, such as food, clothing, housing that is safe and appropriate to our specific needs and life stage, health care, education, time, and space for creative expression and recreation, will consolidate power among the Democrats, and likely produce policies that retrench racial inequalities. I could not disagree more with their conclusions in this regard.

What should be clear to anyone paying attention is that the New Democrats are much more willing to embrace versions of liberal anti-racism than they are willing to make substantial commitments to broadly redistributive public policy. The Bill Clinton administration pioneered this combination of socially liberal public relations and pro-capitalist national economic and social policy, which included workfare reform and the demolition of public housing via HOPE VI legislation. The Obama administration perfected this combination of socially liberal public relations and neoliberal governance, drawing on his claims to racial authenticity to deflect public criticism and popular outrage over black employment and police killings. The current field of Democratic presidential hopefuls features more of the same, with some like Corey Booker, Elizabeth Warren, and Kamala Harris already floating their version of black reparations, in concert with a growing list of neoliberal reparations devotees including Forbes magazine contributors and New York Times columnist David Brooks.[29] Far from opposing a politics of recognition and racial justice, Democratic centrists are in full embrace of underrepresented minorities, as evidenced in triumphant public and partisan interpretations of the 2018 mid-term elections. Equally, they are committed to addressing wealth inequality so long as the proposed policies do not disrupt the sanctity of private property. Put another way, the New Democrats are prepared to do what they have done for the last few decades, continue their low-frequency war against the working class, while embracing racial and gender justice for those who are the most integrated and ideologically-committed to neoliberalism.

The only way I think we can reverse this process, and contest the power of capital, which is enshrined in both parties, is to build working class-centered popular struggles and fight to achieve universal, concrete forms of social justice that improve the lives of the greatest number of Americans. Unlike these authors I believe that politics and context matters, that addressing the expressed needs and desires of working class Americans need not forever be haunted by the alleged and real failings of the New Deal, Fair Deal, or Great Society regimes of national policy-making. This is an ahistorical point that I wish so many on the Left would stop making. It is wrong in terms of historical analysis and politically defeatist as an operating logic. We know that universal policies like Social Security and the national public works programs of the Depression era made life better for millions of Americans. We also know that national anti-discrimination regulation improved the lives of African Americans, expanding the middle class, reducing poverty, and integrating blacks more fully into American life. The lives of millions more could be improved through a combination of universal policies that decommodify housing, education, health care, and transportation, effective anti-discrimination laws that prohibit racist behavior in housing, job markets, and higher education admissions, and federal, state, and local policies that address inequalities in K-12 school district funding, and that strengthen the right to collective bargaining and raise wage floors. As I and others have argued before, broad swaths of the black population have long supported universal, progressive social policies, often with greater intensity than other segments of the US population. Although we recall the sixties as a heyday of black “self-organization“ and the reactionary unionism of George Meany, African Americans were the most likely to join a union during that period. We need a left analysis of American history and contemporary life that proceeds from a clear-headed sense of actually-existing black life. We should not shy away from pursuing these policies because of perceived historical failures, or worse, because of some paranoia of cooptation by the Democratic Party. Both of those concerns seem academic in the worst way to me, divorced from the daily realities and tough choices that many Americans are forced to make at the ballot box and on pay day. The nominal Left is already an adjunct to the Democratic Party, largely because of prevalent antipathy among remnants of Occupy Wall Street and Black Lives Matter towards constituted power, and the real difficulty of building popular power in the pro-capitalist and anti-public environment that neoliberalization has produced. In places where the infrastructure and organizing networks exists, socialists should run for public office and build an independent political base, but this is not possible in some parts of the country. We need a left politics that organizes for power, and draws a keen distinction between supporting Democratic candidates in specific locales where they are a better option, and building a Left politics that cannot be subsumed under the Democratic Party and is ultimately capable of emancipating labor and empowering the masses of Americans. Rustin’s basic majoritarian claim that the Left can only win—and implicitly African Americans can only win—by building powerful alliances capable of imposing popular will and contesting the demands capital makes on the planet and our lives, remains very much in front of us.

Notes

[1] Cruse, “Revolutionary Nationalism and the Afro-American,” Studies on the Left, Vol.2, No.3, 1962, 85.

[2] Cruse, “Revolutionary Nationalism and the Afro-American,” 78.

[3] Mia White, “In Defense of Black Sentiment,” New Politics 27 (Winter 2019), no. 2.

[4] Moody, “Cedric Johnson and the Other Sixties’ Nostalgia,” New Politics 1 March 2019.

[5] James Forman, Jr. Locking Up Our Own: Our Crime and Punishment in Black America (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2017); Michael Javen Fortner, Black Silent Majority: The Rockefeller Drug Laws and the Politics of Punishment (Cambridge and London: Harvard University, 2015); Donna Murch, “Crack in Los Angeles: Crisis, Militarization and Black Response to the Late Twentieth-Century War on Drugs,” Journal of American History 102 (June 2015), no. 1: 162-173.

[6] Stuart Hall, Chas Critcher, Tony Jefferson, John Clarke, and Brian Roberts, Policing the Crisis: Mugging, the State and Law and Order (Palgrave-Macmillan, 2013 [1978]); Ruth Wilson Gilmore, Golden Gulag: Prisons, Surplus, Crisis, and Opposition in Globalizing California (Berkeley & Los Angeles: University of California, 2007); Theodore G. Chiricos and Miriam A. Delone, “Labor Surplus and Punishment: A Review and Assessment of Theory and Evidence,” Social Problems 39 (November 1992), no. 4: 421-446; Todd Gordon, “The Political-Economy of Law-and-Order Policies: Policing, Class Struggle, and Neoliberal Restructuring,” Studies in Political Economy 75 (Spring 2005): 53-77.

[7] Loïc Wacquant, “Class, Race and Hyperincarceration in Revanchist America,” Daedalus (Summer 2010): 74-90; Loïc Wacquant, Punishing the Poor: The Neoliberal Government of Social Insecurity (Durham and London: Duke University, 2009).

[8]Brett Story, “The Prison in the City: Tracking the Neoliberal Life of the ‘Million Dollar Block,” Theoretical Criminology 20 (2016), no. 6: 257-276.

[9] Moody, “Cedric Johnson and the Other Sixties’ Nostalgia,”

[10] Employing the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescents to Adult Health, Nathaniel Lewis has found that “class appears to be a larger factor than usually reported when studying racial disparities” and surprisingly for some, “race is not statistically significant factor for many incarceration outcomes, once class is adequately controlled for.” See Nathaniel Lewis, “Mass Incarceration: New Jim Crow, Class War or Both?” People’s Policy Project, 30 January 2018; Nathaniel Lewis, “Locking Up the Lower Class,” Jacobin, 30 January 2018.

[11] Karl Marx, Capital Volume I (New York: Penguin, 1990), 794-797.

[12] Lucius Couloute and Daniel Kopf, “Out of Prison and Out of Work: Unemployment Among formerly Incarcerated People,” Prison Policy Initiative, July 2018.; Bernadette Rabuy and Daniel Kopf, “Prisons of Poverty: Uncovering the pre-incarceration incomes of the imprisoned,” Prison Policy Initiative, 9 July 2015; Adam Looney and Nicholas Turner, “Work and Opportunity before and After Incarceration,” Brookings Institution, March 2018.

[13] Zhandarka Kurti describes this process in some detail, while remarking on the futility of probation as a reformist strategy given the fact of structural unemployment: “ The requirements to find work and housing and to avoid contact with the police are often basic conditions. The few people who meet these conditions are mostly funneled to low-wage work in the service industry. Probation officers are ill equipped to find people jobs; they can only recommend numerous job-training and workforce programs in the hopes that participating in these dissuade young folks from a life of crime . . . Today more than ever, the idea that work can transform ‘criminals’ into ‘productive citizens’ is dubious at best. Increased economic insecurity and low-wage jobs make ‘productive citizenship,’ the penal-welfarist goal on which probation was founded, seem like a pipe dream. Instead, the function of community supervision resembles more that of the prison: a way to manage poverty and growing surplus populations in deindustrialized urban cores. The success of second chance programs that rely heavily on probation depends not on how well rigid organizational bureaucracies embrace ‘change,’ which is how many liberal reformers frame it, but the extent to which each state and county can absorb surplus populations.” See, Zhandarka Kurti, “Second Chances in the Era of the Jobless Future,” Brooklyn Rail, 5 March 2018.

[14] Jamie Peck and Nik Theodore, “Carceral Chicago: Making the Ex-offender Employability Crisis,” International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 32 (June 2008), no. 2: 251-81; On the broader context of low-wage work in Chicago, see Marc Doussard, Degraded Work: The Struggle at the Bottom of the Labor Market (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota, 2013).

[15] Peck and Theodore, “Carceral Chicago,” 276.

[16] Neil Smith, The New Urban Frontier: Gentrification and the Revanchist City (London: Routledge, 1996); Neil Smith, “Revanchist Planet: Regeneration and the Axis of Co-Evilism,” Urban Reinventors Paper Series, 2005-2009; Mike Davis, City of Quartz: Excavating the Future in Los Angeles (New York: Penguin, 1992); Don Mitchell, “Against Safety, Against Security: Reinvigorating Urban Life,” Michael J. Thompson, Fleeing the City: Studies in the Culture and Politics of Antiurbanism (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2009), 233-248; Timothy Gibson, Securing the Spectacular City: The Politics of Revitalization and Homelessness in Downtown Seattle (Lanham: Lexington Books, 2004); Alex Vitale, City of Disorder: How the Quality of Life Campaign Transformed New York Politics (New York: New York University, 2008); Ayobami Laniyonu, “Coffee Shops and Street Stops: Policing Practices in Gentrifying Neighborhoods,” Urban Affairs Review 54 (2018), no. 5: 898-930; Elaine B. Sharp, “Politics, Economics and Urban Policing: The Postindustrial City Thesis and Rival Explanations of Heightened Order Maintenance Policing,” Urban Affairs Review 50 (2013), no. 3: 340-65; Stuart Forrest, Down, Out and Under Arrest: Policing and Everyday Life in Skid Row (Chicago: University of Chicago, 2016).

[17] Eli Hager, “A Mass Incarceration Mystery: Why Are Black Imprisonment Rates Going Down? Four Theories,” The Marshall Project, 15 December 2017.

[18] Ira Katznelson, When Affirmative Action Was White: An Untold Story of Twentieth Century Racial Inequality in Twentieth Century America (New York and London: W.W. Norton, 2005); Ta-Nehisi Coates, “The Case for Reparations,” The Atlantic, June 2014.

[19] Touré Reed, “Obama and Coates: Post-racialism’s and Post-post-racialism’s Yin-Yang Twins of Neoliberal Benign Neglect,” Catalyst (2018); see also, Larry Dewitt, “The Decision to Exclude Agricultural and Domestic Workers from the 1935 Social Security Act,” Social Security Bulletin 70 (2010), no. 4: 3-4.

[20] Neil M. Maher, Nature’s New Deal: The Civilian Conservation Corps and the Roots of the American Environmental Movement (Oxford and New York: Oxford University, 2008); Nick Taylor, American-Made: The Enduring Legacy of the WPA: When FDR Put the Nation to Work (New York: Bantam, 2009).

[21] Luther C. Wandall, “A Negro in the CCC,” Crisis 42 (August 1935): 244, 253-54; from the New Deal Network, “African Americans in the Civilian Conservation Corps.”

[22] Another favored target of the “constraint of race” discourse is the G.I. Bill. I can’t say how many times in the last decade I’ve had a student in my courses, or an audience participant after a lecture make the claim that blacks did not benefit from the G.I. Bill’s provisions. This claim runs a close second to the myth about Social Security as a rhetorical move to short circuit any talk of fighting for universal public policy in our times. Suzanne Mettler offers a healing balm against this contagion. In her study of the G.I. Bill and African American veterans, she concludes: “Contrary to the assumption that African Americans had little access to the G. I. Bill, Veterans’ Administration records verify that, over the first five years of the program, higher proportions of nonwhites than whites used the law’s education and training benefits . . .[By] 1950 49 percent of nonwhite veterans had used the benefit compared to 43 percent of white veterans. The provisions were used at especially high rates in the South, where 51 percent of all veterans had entered some kind of education or training by 1950. Strikingly, nonwhite southern veteran’s usage surpassed that of white veterans in the region, at 56 percent compared to 50 percent. Similarly, in the West, 46 percent of nonwhite veterans went to school on the G. I. Bill, compared to 42 percent of white veterans. Nationwide, black World War II veterans numbered 1,308,000; already by 1950, 640,920 of them had benefited from the G.I. Bill’s education and training provisions.” Suzanne Mettler, “’The Only Good Thing Was the G. I. Bill:’ Effects of the Education and Training Provisions on African-American Veterans’ Political Participation,” Studies in American Political Development 19 (Spring 2005), 31-52; See also, Michael J. Bennett, When Dreams Came True: The GI Bill and the Making of Modern America (Washington: Brassey’s, 1996).

[23] Lizabeth Cohen, Making a New Deal: Industrial Workers in Chicago, 1919-1939 (Cambridge: Cambridge University, 1990); Ahmed White, The Last Great Strike: Little Steel, the CIO and the Struggle for Labor Rights in New Deal America (Oakland: University of California, 2016); Charles D. Chamberlain, Victory at Home: Manpower and Race in the American South during World War II (Athens and London: University of Georgia Press, 2003).

[24] Will P. Jones, The March on Washington: Jobs, Freedom and the Forgotten History of Civil Rights (New York: W.W. Norton, 2014).

[25] See, Rhonda F. Levine, Class Struggle and the New Deal: Industrial Labor, Industrial Capital and the State (Lawrence: University of Kansas, 1988); Meg Jacobs, “’Democracy’s Third Estate’: New Deal Politics and the Construction of a ‘Consuming Public,’” International Labor and Working-Class History (Spring 1999), no. 55: 27-51.

[26] Judith Stein, Running Steel, Running America: Race, Economic Policy and the Decline of Liberalism (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina, 1998).

[27] Cedric Johnson, Revolutionaries to Race Leaders: Black Power and the Making of African American Politics (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota, 2007), 35-39; Stephen Steinberg, “Bayard Rustin and the Rise and Decline of the Black Protest Movement,” New Politics 6 (Summer 1997), no. 3.

[28] Gregor Baszak, “Marxism Through the Backdoor: An Interview with Cedric Johnson,” Platypus Review 79 (September 2015).

[29] David Brooks, “The Case for Reparations,” New York Times, 7 March 2019; Christian Weller, “Only Large Interventions Such as Reparations Can Shrink the Wealth Gap,” Forbes 21 March 2019 ; Callum Paton, “Kamala Harris Says Slavery Led to Untreated ‘Physiological Outcomes,’ Supports Reparations as Mental Health Issue,” Newsweek, 14 March 2019.

The foul, brutal hands of U.S. imperialism and its allies are tightening around Venezuela, and there is a strong possibility that a far-right takeover will occur in the near future. This would extinguish the last vestiges of the left-of-center Pink Tide in South America. If this occurs, an entire region, from Argentina to Brazil to Venezuela, would be in the hands of the far right in a manner not seen since the military coups of the 1960s and 1970s that produced a Southern Cone of torture and murder. While the situation today is different, it is virtually certain that a brutal crackdown on left-wing and labor movements, as well as on indigenous communities, would follow the overthrow of Venezuela’s Maduro government. This would especially be the case if there is armed resistance, which there is very likely to be, since while Maduro’s authoritarian policies and the economic collapse have alienated many working people, even low estimates suggest the government retains about 20% popular support.

The foul, brutal hands of U.S. imperialism and its allies are tightening around Venezuela, and there is a strong possibility that a far-right takeover will occur in the near future. This would extinguish the last vestiges of the left-of-center Pink Tide in South America. If this occurs, an entire region, from Argentina to Brazil to Venezuela, would be in the hands of the far right in a manner not seen since the military coups of the 1960s and 1970s that produced a Southern Cone of torture and murder. While the situation today is different, it is virtually certain that a brutal crackdown on left-wing and labor movements, as well as on indigenous communities, would follow the overthrow of Venezuela’s Maduro government. This would especially be the case if there is armed resistance, which there is very likely to be, since while Maduro’s authoritarian policies and the economic collapse have alienated many working people, even low estimates suggest the government retains about 20% popular support.

It’s been more than a month since the crucial event in political life of Moldova took place – the February parliament elections. The elections define the future development of the country, which is a parliamentary republic.

It’s been more than a month since the crucial event in political life of Moldova took place – the February parliament elections. The elections define the future development of the country, which is a parliamentary republic.

Over the last five years, Black Lives Matter has served as a broad banner uniting citizens from all walks of life against the most egregious and visible use of police force against black civilians. Until the election of Donald Trump, who made his “Blue Lives Matter” commitments well-known from the very moment he announced his candidacy, popular demonstrations against police killings spread like prairie fires across the country from Oakland to Ferguson, Missouri, and on to Baltimore, Chicago, Dallas, and Baton Rouge. As a rallying cry, Black Lives Matter opened up public space for disparate campaigns, networks of grieving families, criminal justice reform organizations, and localized struggles against the carceral state that had been in motion for decades. At the same time, however, like most great slogans, #BlackLivesMatter advanced a rather straightforward, if not simplistic analysis of the issue at hand, that the problems of policing were primarily racial. Black Lives Matter fervor also unleashed a torrent of historical misinformation, conspiracy theory, and wrong-headed thinking about politics. In elevating a race-centric interpretation of American life and history, Black Lives Matter has actually had the effect of making it more difficult to think critically and honestly about black life as it exists, in all of its complexity and contradictions. Rather than clearing a path through the thickets, some left intellectuals have made peace with this overgrowth of bad historical thinking, even though it threatens to choke out the possibility for cultivating the kind of critical left analyses of society we so desperately need.

Over the last five years, Black Lives Matter has served as a broad banner uniting citizens from all walks of life against the most egregious and visible use of police force against black civilians. Until the election of Donald Trump, who made his “Blue Lives Matter” commitments well-known from the very moment he announced his candidacy, popular demonstrations against police killings spread like prairie fires across the country from Oakland to Ferguson, Missouri, and on to Baltimore, Chicago, Dallas, and Baton Rouge. As a rallying cry, Black Lives Matter opened up public space for disparate campaigns, networks of grieving families, criminal justice reform organizations, and localized struggles against the carceral state that had been in motion for decades. At the same time, however, like most great slogans, #BlackLivesMatter advanced a rather straightforward, if not simplistic analysis of the issue at hand, that the problems of policing were primarily racial. Black Lives Matter fervor also unleashed a torrent of historical misinformation, conspiracy theory, and wrong-headed thinking about politics. In elevating a race-centric interpretation of American life and history, Black Lives Matter has actually had the effect of making it more difficult to think critically and honestly about black life as it exists, in all of its complexity and contradictions. Rather than clearing a path through the thickets, some left intellectuals have made peace with this overgrowth of bad historical thinking, even though it threatens to choke out the possibility for cultivating the kind of critical left analyses of society we so desperately need.

Comrades Lapavitsas and Blakeley,

Comrades Lapavitsas and Blakeley,

April 2, 2019

April 2, 2019

It happens all the time in small towns and big cities across the country. A young person from a poor or working-class family can’t find a good job or afford to pay for higher education. Other family members, a teacher, coach or guidance counselor—who have been in the armed forces themselves—encourage them to enlist. Military service promises an escape from the dead-ends and disappointments of civilian life. It offers steady employment with benefits, now and later. By signing up, you can learn a skill, see the world. Overcome challenges. Make yourself into a leader. Become an army of one.

It happens all the time in small towns and big cities across the country. A young person from a poor or working-class family can’t find a good job or afford to pay for higher education. Other family members, a teacher, coach or guidance counselor—who have been in the armed forces themselves—encourage them to enlist. Military service promises an escape from the dead-ends and disappointments of civilian life. It offers steady employment with benefits, now and later. By signing up, you can learn a skill, see the world. Overcome challenges. Make yourself into a leader. Become an army of one.

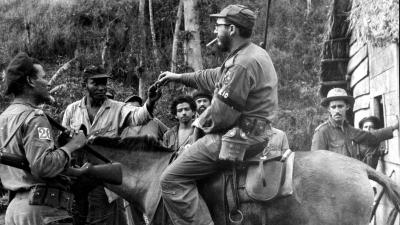

Cuba has not been at the center of world attention for a long time, particularly after the collapse of the Soviet bloc considerably diminished the island’s importance to US imperialism. For the international left, political developments in other Latin American countries, especially Venezuela, have surpassed Cuba as a primary focus of attention. That does not mean, however, that the Cuban model has ceased to be a desirable, even if at present unrealizable, model for significant sections of the left, particularly in Latin America. For larger sections of the left, there is still considerable misinformation and confusion about the true nature of Cuba’s “really existing socialism,” a confusion that far from being of merely academic interest has a significant impact on the left’s conception of socialism and democracy. The lack of democracy and therefore of authentic socialism in Cuba is not only a problem of interest to Cubans, but also a critical test of how seriously the international left takes its democratic pronouncements.