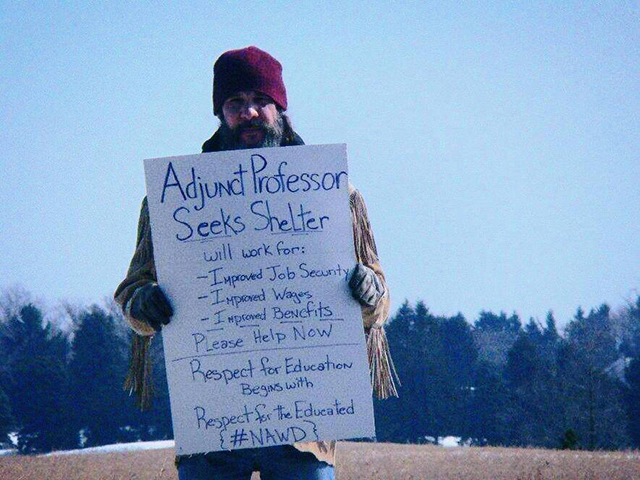

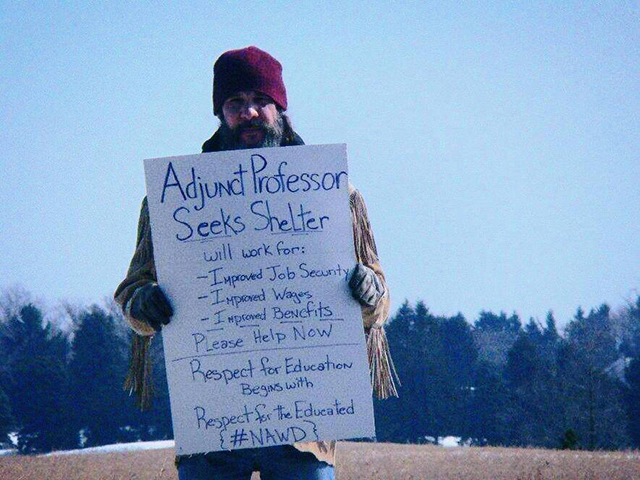

A message put forward in our capitalist society is if people get a college education, they will likely get better-paying jobs. However, there are many with college degrees who endure insecure working conditions and are poorly compensated. They include part-time teachers in institutions of higher education, most of whom have advanced degrees. According to the American Association of University Professors, part-timers hold over 65% of faculty positions in two-year institutions and almost 50% at master’s and baccalaureate institutions. They, along with adjuncts who teach full-time, make up over 70% of the instructional workforce in higher education and teach more than half the undergraduate classes in public institutions.[1] A third of them make less than $2,000 per class.[2] Many live in conditions of poverty and rely on public assistance.[3]

A message put forward in our capitalist society is if people get a college education, they will likely get better-paying jobs. However, there are many with college degrees who endure insecure working conditions and are poorly compensated. They include part-time teachers in institutions of higher education, most of whom have advanced degrees. According to the American Association of University Professors, part-timers hold over 65% of faculty positions in two-year institutions and almost 50% at master’s and baccalaureate institutions. They, along with adjuncts who teach full-time, make up over 70% of the instructional workforce in higher education and teach more than half the undergraduate classes in public institutions.[1] A third of them make less than $2,000 per class.[2] Many live in conditions of poverty and rely on public assistance.[3]

In her 2015 Atlantic article, “There Is No Excuse for How Universities Treat Adjuncts,” Caroline Frederickson points out,

“Based on data from the American Community Survey, 31 percent of part-time faculty are living near or below the federal poverty line. And, according to the UC Berkeley Labor Center, one in four families of part-time faculty are enrolled in at least one public assistance program like food stamps and Medicaid or qualify for the Earned Income Tax Credit.”[4]

A key reason why many part-time faculty live in poverty is due to the weakness of workers and their unions. For many years, the pay of workers has not been keeping up with increases in the cost of living despite gains in worker productivity. [5] The weakness of labor has been aided by government policies favorable to the rich that in the case of college teachers, are enforced by school administrators and, unfortunately, too often aided by leaders of teacher unions.

Capitalism and Exploited Part-Time Teachers

Successful business owners in a capitalist society must maximize profits to foster growth through the accumulation of capital. For most businesses, exploiting workers–paying them as little as possible (which could be costly if there are few workers with needed skills,) and getting them to work as hard as possible increases potential profits.

Exploited teachers do not necessarily directly produce what Marxists would call surplus value, the basis for profits. However, they play a vital role in reproducing the system. They train the future workers with skills wanted by business. They also pass on the class-based capitalist culture that helps to create conditions in which workers can be effectively dominated and exploited. Additionally, they train the future managers and supervisors of the system–even future owners.

Many educators endure the same forms of worker degradation and domination by management described by Harry Braverman in his book Labor and Monopoly Capitalism. Administrators of schools will act to cheapen labor costs by enforcing policies to increase teacher productivity which is the teaching of classes with more students. They also help in the undertaking of efforts to standardize what is taught rendering teachers more easily replaceable. Administrators will also help with the introduction of cost saving technology to replace the paid work done by teachers.

Corporate-minded managers of teachers treat education like an assembly line–with teachers adding value by processing students through their classes. Management will assert that success is achieved when students end up as finished products—exploitable, compliant and obedient workers with a set of skills needed by business, or employees who can oversee and enforce the exploitation of others.

Management of higher educational institutions will act to hold down costs by hiring part-timers. From where do they find these teachers? Many have been “produced” by graduate programs. Those overseeing these programs justify their existence by enrolling an excessive number of students, many of whom seek to become full-time college teachers with tenure. Graduate students and recent graduates who have a goal of holding a secure full-time tenured position are more than willing to take on what they believe is temporary work as underpaid part-time teachers. Unfortunately for many, that full-time job with tenure will never be offered. Even if that ideal job is acquired, it may not last long.

Part-time Faculty

There is much variety among those who teach part-time. They can include retired full-time faculty returning to teach a class or two. In the past, part-time faculty were often educated wives of university tenured professors or, as is true today, people who had outside jobs and expertise.[6] The latter’s presence in the classroom is sought to provide students with knowledge from those with practical experience in particular fields. Their teaching work is a side job usually done for satisfaction, often at a low rate of pay that is not vital for their well-being.

Today, many part-timers work as teachers is their primary source of income.[7] Educational institutions have become increasingly dependent on a part-time workforce. The use of part-timers lowers a college’s operating costs. For example, many part-timers are not provided with office space. They will resort to using the trunk of their car for storing materials they need in order to do their job.

The lower cost of part-timers frees up money that can be used to hire more administrators, for financing new facilities and to increase the pay of full-time faculty to secure their loyalty.[8]

Frederickson describes the changes taking place at colleges as more full-time adjuncts and part-timers are hired.

“In 1969, almost 80 percent of college faculty members were tenure or tenure track. Today, the numbers have essentially flipped, with two-thirds of faculty now non-tenure and half of those working only part-time, often with several different teaching jobs…That colleges and universities have turned more and more of their frontline employees into part-time contractors suggests how far they have drifted from what they say they are all about (teaching students) to what they are increasingly all about (conducting research, running sports franchises, or, among for-profits, delivering shareholder value).”[9]

There are other incentives for hiring part-time teachers besides their lower labor costs. Part-timers tend to be heavily compliant workers. They have been “trained” in the system and generally accept its protocols and procedures that include respect for the existing institutions and the authority of those above them. Many part-timers avoid exercising their right to academic freedom. They will not risk losing work by expressing unconventional ideas that they believe people in positions of authority will find controversial, unacceptable or unprofessional.

Part-timers are a flexible workforce that is hired only when needed. They can be easily and quickly dismissed. They are qualified to teach the classes assigned. The grades they give students are as valid as those given by full-time tenured professors. The tuition charges and the money generated based on enrollment are the same whether a class is taught by a full-timer or part-timer.

Many part-timers are passionate about being teachers. They are often willing to make great efforts and many sacrifices to keep their insecure positions. They can be taken advantage of because many are hoping to be considered for that “ideal” full-time, well-paid, tenured-track position, and will volunteer to do extra unpaid administrative work.

Educational power hierarchies reinforce the subordinate position of part-timers. Within an educational institution, most power rests with the administration. Among educators, the remaining power is mostly held by full-timers with tenure who are involved in hiring, supervising and evaluating part-timers and non-tenured track full-time adjuncts. Adjuncts and part-timers do not hire, supervise and evaluate full-timers. Instead, they are highly dependent for their jobs on the goodwill of their full-time “colleagues.” Furthermore, their subordinate position is reinforced when, as happens at many colleges, they are not invited to participate in faculty meetings and are the first to lose their jobs when management declares there is a budget crisis requiring cuts.

Unfortunately, some part-timers themselves, especially if they seek to move ahead, or are close to management, aid and abet this exploitative system.

Hierarchies exist among part-timers and create divisions that management can use to its advantage. Part-timers who have put in many years at a college generally have greater job security. They may have contracts that guarantee work for more than one term, or they benefit from a modest seniority system that guarantees their job over a less senior part-time faculty member. However, more “privileged” part-timers continue to be vulnerable since other part-timers can be hired to take their jobs at a lower rate of pay.

The Role of Unions

Unions are vital for improving the living standards and providing greater job security for workers. Without unions, workers would receive lower pay and benefits, be more dominated, endure inferior working conditions, and have less secure jobs.

Unfortunately, many teacher union leaders too often place a greater emphasis on helping the administration achieve its goals even when their goals are contrary to the interests of teachers, especially part-timers. These goals include keeping costs down, increasing productivity through the use of fewer workers, and maintaining labor peace.[10]

The recently retired communications director of the California Federation of Teachers (CFT) reflects this mindset of wanting to maintain stability in the workplace. In a column he authored before the Los Angeles teachers strike, he characterizes the states in which there were wildcat teacher strikes in the first part of 2018 as “less enlightened…right to work states” with “abysmally poor funding for education.”[11] For him, these states had not caught up with his apparent model, California. He contends that California, with its “collective bargaining laws,” has not had “a sustained wave of public employee militancy” in 40 years. Instead, it has had “public workplace stability,” something obviously desired by management.

California has what he states are “relatively strong education unions.” Yet, the conditions of part-time faculty have remained unjust. Voters in California approved a union sponsored tax bill in 2012 that was renewed in 2016 that the CFT claims is raising some $6 billion annually for public education and is supposedly preventing a “return to austerity.”[12] However, many teachers, especially part-timers, represented by CFT locals have levels of pay that have not kept up with increases in the cost of living. (See appendix #1) [13]

Union Leaders’ Claims vs. Reality

Many teachers, including their union leaders, tend to see themselves as embracing social justice, fighting for equality and working on behalf of students who may face great obstacles in life. At their union meetings, they will encourage the passing of resolutions in support of organizations struggling for social justice throughout the world.

However, too many unions and their leaders make little or no effort to end the inferior treatment of part-time faculty members. An example is my own local union affiliate of the American Federation of Teachers (AFT), AFT 2121. It represents faculty at the two-year community college, City College of San Francisco (CCSF) in a city overwhelmingly dominated by the Democratic Party that is known as a “union town” with politics considered far to the “left” of most of the rest of the country.

Past struggles of part-timers at CCSF have resulted in them having some job security protections and in being among the highest paid part-timers in the nation. For example, in 2017 in the nearby Contra Costa district, part-timers were paid $74.19 per hour in the classroom while those at CCSF were making $104.95.[14] At City University of New York whose part-time faculty are also represented by an AFT affiliate, average pay for one teaching a three unit class is $3,500. By contrast, at CCSF, the starting pay for a part-timer teaching a three-unit course is over $5,400 and can be over $8,000 for those who have taught at the college for more than 20 years.

Nevertheless, the pay and benefits part-timers at CCSF receive illustrate AFT 2121’s shortcomings.

The leaders of AFT 2121 assert that they favor equal pay for equal work meaning part-timers should receive the same rate of pay per class as full-timers.[15] AFT 2121 leaders endorse candidates for office such as Jane Kim (who ran for mayor of San Francisco in 2018) who, in response to a union questionnaire, stated, “Part-time faculty should have pay commensurate to full time faculty and be paid equal pay for equal work.”[16]

However, in recent contract negotiations, the union leadership has not put forward demands calling for equal pay for equal work.[17] This results in management not having to resist movement towards equal pay for equal work since the union leadership itself is helping to perpetuate the unjust and unequal treatment of part-timers.

The union leadership will state that the pay of part-time teachers at CCSF is 86% of that received by full-timers, not 100%, because full-timers, unlike part-timers, are expected to do additional work for their department and serve on committees.[18] However, when teaching, some full-time and part-time teachers put in many more hours than others for which they are not paid. Some full-timers, especially once they get tenure, do little besides teaching. When doing committee work, some are active participants and put in many hours while others will get credit for doing this work even if all they do is to passively sit through meetings.

Furthermore, some full-timers take on additional tasks to line themselves up for higher-paying jobs as administrators. They may even end up siding with management over the interest of teachers in order to secure a promotion into an administrative position. Paying these full-timers at a higher rate than part-timers is unjustified.

Many part-timers adhere to an unwritten rule that they must do unpaid administrative work in order to be seriously considered for a full-time position.

Almost all CCSF part-time teachers’ actual pay is much lower than 86% of what full-timers with the same educational level are paid. Full-timers move up the pay scale every year they teach. By contrast, part-timers move up every two years. The part-timer may start the first year at 86%, but that percent will soon decline. After ten years, the pro-rata percent is under 73% with the full-timer’s pay increasing by over $2,400 per three-unit class taught while the part-timer’s increase comes to less than $1,000. (For more details, see appendix #2.)

Over time, the work of part-timers compared to full-timers becomes relatively cheaper. Meanwhile, the college receives the same amount of money from the state whether a class is taught by a part-timer or full-timer. Were the college a business, over time, the part-timer’s labor that is similar to a full-timer’s labor generates more profits for the business.

Unequal Benefits and Unfair Burdens

Additionally, part-timers at CCSF lack many of the benefits provided to full-timers. Unlike full-timers, they do not receive retiree health coverage, paid sabbaticals, and life insurance. Full-timers receive disability insurance. Part-timers must pay for it.

If part-timers teach at least 50% of the class units taught by a full-timer, they are eligible for the same medical benefits as full-timers. However, to pay for this benefit, part-timers have the same amount of money taken from their pay as do full-timers, paying a larger percent of their lower income.

The percent of part-timers receiving medical benefits has declined from 50% in 2012 to 32% as of 2017 when fewer part-timers were employed.[19] AFT 2121 favors a single payer medical system.[20] However, its leaders have accepted the college reaping significant savings from fewer part-time faculty having medical coverage. During the 2017-18 contract negotiations, union leaders failed to demand increases in the number of part-timers receiving medical benefits. Those demands could have included a call to lower the required units taught before one is eligible for medical benefits and to insist on coverage for those receiving it the previous term.

Part-timers at CCSF are more burdened when paying union dues. Dues are a regressive flat 1.5% of one’s income no matter how much one earns. Those least able to pay have to pay at the same rate as those making more money.

Upon retirement, full-timers will have greater economic security from larger pensions that are based on one’s earnings. Lower paid part-timers will presumably have to work longer because, with lower payments in retirement, they will less likely be able to afford to retire.

Over time, taking benefits and pay into account, the total value of the salary and benefits package of part-time teachers relative to full-timers at CCSF is much below 86%, perhaps closer to 60%.

Lack of Job Security

Part-timers’ job security is far inferior to that of full-timers. At CCSF and at other colleges, full-timers are guaranteed a full schedule before any part-timer is assigned a class. When the administration at CCSF cuts a class of a full-timer due to low enrollment, the current level of pay is not cut. The full-timer is expected to teach an additional class in the future or do other acceptable work. By contrast, a part-timer losing a class due to low enrollment loses pay and will not be given an additional class to teach in the future.

In many colleges, full-timers losing a class due to low enrollment have a bump right that allows them to take over and teach a scheduled class of a part-timer even after the part-timer has spent unpaid time preparing to teach the class.

At CCSF, when the previous contract was being negotiated in 2015, the administration announced plans to cut 25% of the scheduled classes at 5% per year over the next 5 years. These cuts would be predominantly absorbed by part-timers. The union president said the planned cuts could not be negotiated—that the decision to cut classes is a prerogative of the administration.[21]

In other words, union leaders did nothing about the planned loss of work endured by the people they supposedly represent who pay union dues. Nevertheless, despite members losing work, union leaders declared the negotiated contract a “victory.”[22]

The leaders also touted how everyone would receive a pay increase.[23] However, they did not acknowledge that part-timers losing classes, or even their jobs due to class cuts, would make less income. These part-timers could have been doing better before this pay “increase” because they were teaching more classes.

Latest Faculty Contract at CCSF

In 2018, a new contract was negotiated. The leadership described the contract and its ratification as

“a great victory for public education and the entire San Francisco community. We are so happy that this will help our faculty continue to do the jobs they love and serve our students and all of San Francisco….We want to thank the Board of Trustees, the Chancellor and the District Negotiations team for working with us.”[24] (emphasis added)

Absent from this happy talk was an honest discussion of the contents of this contract.

Once again, the needs and interests of part-timers were largely disregarded even though they make up over 60% of the faculty. The contract resulted in increasing the pay gap between full-timers and part-timers, and also between the highest paid full-timers and more recently hired full-timers. (See appendix 3)

By not putting forward demands in negotiations and struggling to reduce unequal pay for the same work, union leaders like those in AFT 2121 could “be considered complicit in a violation of Human Rights.”[25]

Union Dues Enrich Union Officials

Much of the union dues paid to one’s local that is part of a national union end up being transferred to the union’s state and national organizations. My own local’s fiscal year 2014 tax return shows that $1.03 million in dues was collected and over $730,000 was transferred to the statewide CFT and the nationwide AFT.[26]

The transfer of dues paid enables many top officials in the national and state union organizations to have large salary packages. In 2015, six top officials in the CFT each received salary packages in excess of $270,000.[27] In 2016, AFT president Randi Weingarten’s pay package was for over $510,000, up more than 10% from the previous year.[28]

The leaders’ salary packages are being partly financed by impoverished, job insecure, part-timers and far exceed what most teachers earn. According to the National Education Association, the average public school teacher made $59,660 in 2016-17.

Troubles Ahead

Labor unions have been under attack for years resulting in fewer workers belonging to unions. A recent assault on public unions came with the June 2018 Supreme Court Janus decision. It eliminated the requirement that all public employees represented by a union, even those who are not members, pay fees/dues to the union. Now, only union members will pay dues resulting in unions collecting less money and presumably becoming weaker unless every worker joins the union.[29]

Adding to the woes of teacher unions would be planned class cuts as are happening at CCSF and described in AFT 2121literature as, “massive.” Class cuts will result in a further loss of dues revenue since faculty income that determines the amount of dues collected will be lower.[30]

Obstacles Facing Part-timers

Part-timers need to be organized to struggle if they want to improve their conditions. However, they face many obstacles. They are often isolated from other faculty. Part-timers may have few, if any, connections or means to communicate with other part-timers. They frequently do not even know others teaching in their own department. Many teach in more than one college and have little, if any, time to devote to job-related struggles at a single college.

The working conditions, level of pay, and job security of part-timers can vary greatly and give rise to divisions among them. Some part-timers have reliable relatively higher paid jobs for many years while the most marginalized are given one class for only one term, and will not be hired to teach at the particular college again.[31] Many part-timers, facing difficulties supporting themselves and their families, will give up trying to work as teachers.

Part-timers are under tremendous pressure to not be involved in any activity around improving their conditions. By being active, they may put in jeopardy both their current employment and future employment when they need recommendations from where they previously worked.

Many faculty members, including part-timers, see themselves not as workers but as professionals who should have little involvement in union activities. They view unions as service agencies and not as organizations that struggle with management to secure better conditions for their members.

Part-timers seeking to improve their situation could benefit from the support of full-timers. This support is often not forthcoming.

Tenured full-time faculty are privileged compared to most workers. They do work that can be satisfying, enjoyable and stimulating. They have much job security and some autonomy. Their income is higher than that of most workers. Many full-timers see little reason for challenging management on any issue. Some full-timers hold attitudes of superiority over part-timers, even viewing them as losers.

Recently at CCSF, management has not needed to resort to creating more divisions between full-timers and part-timers. Many full-timers at CCSF view their relatively low pay (until the newest contract) compared to full-timers elsewhere as resulting from “overpaid” part-timers. They will even claim the union is too focused on championing the interests of part-timers!

An ongoing problem for organizers is that many faculty are unmotivated or legitimately claim they are too exhausted or too busy especially if their work load has been increasing.

Organizing Part-Timers

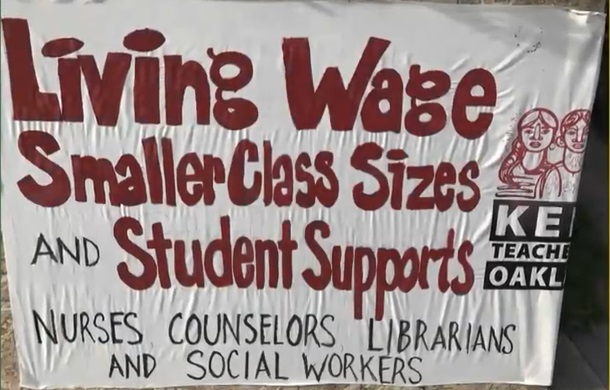

All of the above is not to make excuses, but to acknowledge the great difficulties faced by those trying to organize part-time faculty members. Part-timers wanting to improve their conditions must struggle and change power relationships by building alliances with supportive full-timers, students, staff, and community members.

Key to making favorable changes is the formation of a core group of part-timers who are united around what they want. This core group needs to repeatedly assert their interests and put forward their demands. Other part-timers will support them since all want to be treated equally, and with dignity and respect.

The core group must both communicate with their supporters and integrate them into the core group. Members must be able to make decisions about goals and strategies in contrast to having decisions handed down as happens too frequently in unions. When members own the decisions made, they are more likely to struggle to implement them.

Over time, organizing beyond a single school or district will be necessary for success. Building more effective regional, statewide, national and even international organizations beyond what currently exists is needed.

Demands to Put Forward

Job security and equal pay and benefits for equal work are at the heart of part-timers’ demands. Part-timers having the same seniority and tenure rights as full-timers should also be demanded so that a part-timer with more seniority than a full-timer gets class and scheduling priorities before a full-timer with less seniority does.

Principles of equality are violated when part-timers are exploited and treated as second class faculty members. Only when part-timers get organized and struggle can they bring an end to their exploitation.

[1] See California Federation of Teachers and Adjunct Faculty, Facts, and Characteristics of Postsecondary faculty.

[2] Ibid.

[3] Gee, Alastair, Facing Poverty, Academics Turn to Sex Work and Sleeping in Cars, Guardian 9/28/2017.

[4] Frederickson, Caroline, “There Is No Excuse for How Universities Treat Adjuncts,” The Atlantic, Sept. 15, 2015.

[5] Desilver, Drew, “For Most Workers, Real Wages have Barely Budged in Decades,” Pew Research Center, August 7, 2018, and “The Productivity-Pay Gap,” Economic Policy Institute, August 2018.

[6] Fredrickson op. cit.

[7] American Association of University Professors: Trends in the Academic Labor Force 1975-2015, Chart, Background Facts on Contingent Faculty Positions

[8] Fredrickson op. cit. From this article:

“Even while keeping funding for instruction relatively flat, universities increased the number of administrator positions by 60 percent between 1993 and 2009, 10 times the rate at which they added tenured positions… So while college tuition surged from 2003 to 2013 by 94 percent at public institutions and 74 percent at private, nonprofit schools, and student debt has climbed to over $1.2 trillion, much of that money has been going to ensure higher pay for a burgeoning legion of bureaucrats.”

[9] Ibid.

[10] Gordon, Craig, “Which Side Are Union ‘Leaders’ On?” Counterpunch, 4/27/2018.

[11] Glass, Fred, “United Effort of Striking Teachers and Parents Can Raise Pay, School Quality,” San Francisco Chronicle, 4/14/2018. Glass goes on to write that this view “misses the bigger picture” that includes “the resurgence of progressive political activism following Donald Trump’s election.”

[12] See CFT publication California Teacher, April-May 2018 pgs. 2, 13, 14.

[13] Even with California’s “relatively strong education unions,” and $6 billion more in funding for public education, the February-March 2018 issue of the CFT’s own publication, California Teacher, indicates that California ranks 43rd in preK-12 per pupil funding. And this is happening in a wealthy state dominated by elected Democratic officials, many of whom the CFT endorsed.

See Baum, Rick, “California Democrats Starve Public Education,” Counterpunch, 9/17/2015 and What Can We Expect From the Democrat “Alternative” Given Their Record in California?, Counterpunch, 11/19/18.

[14] See here, pp. 7, 8. Faculty in the Contra Costa district are represented by an independent union. When I taught in that district more than 25 years ago teaching classes about democracy in the United States, a vote on any matter cast by a part-timer counted for one-third. UC Berkeley is at the upper end of part-timers pay with starting pay at more than $8,500 per class. However, most teach only one or two classes a term. See Burawoy and Johnson-Hanks, Second Class Citizens: A Survey of Berkeley Lecturers, pp. 8, 10.

[15] An AFT 2121 Bulletin dated April 23, 2018 sent out to members covers a 2002 parity agreement “defining part-time pay equity under California’s “equal pay for equal work” statute as 100% pro-rata.”

[16] http://www.aft2121.org/wp-content/uploads/Jane-Kim.pdf p. 5. Labor contracts in California community colleges are negotiated in each district resulting in differences in pay and benefits for the same work within the state.

[17] The AFT 2121 sunshine document contained this statement: “Move towards pay equity for assignments currently paid less than 100%, such as lab, part-time…” Absent from the salary proposal put forward in negotiations was a provision for pay equity. see here and union salary proposal, Full AFT 2121 salary proposal.

[18] The AFT 2121 leaders do not publicize that the pay of part-time counselors and librarians start at 100% pro rata before declining. They have made no effort to bring part-time teachers to this level.

[19] Stand Together—The Only Way Forward, 5/30/17.

[20] Who Stole My Raise? 2/7/18

[21] Something to be thankful for: Union power!? AFT 2121 CCSF Pres Says Union Can’t Strike Over 26%,” YouTube, December 13, 2015. The union president’s remarks begin around 4:00.

[22] CCSF Faculty Reach Tentative Agreement with CCSF District Administration, 7/13/16.

[23] Faculty Union, CCSF Administration Reach Tentative Contract Agreement, 7/24/16.

[24] 94%!! Faculty Overwhelmingly Ratify Contract. 5/19/18. 421 faculty voted. There are more than 1,300 faculty members.

[25] COCAL Proposal to End Contingency: Contingent Faculty Bill of Rights, 12/26/2016.

From page 6 Equal Pay. “The principle of “equal pay for equal work” shall be honored. All faculty shall be compensated according to a single salary schedule that recognizes length of service and professional development. If the disparity in tenured and non-tenured compensation rates are so significant that equal pay cannot be implemented in a single budget year, a multi-year phased-in solution shall be permissible.”

From page 7 Unions. “A union has the obligation to honor its duty of fair representation, which means calling for equality in working conditions. When a union does not strive to defend equal working conditions for those for whom it represent or favors one class of union member over another class of union member, that union shall be considered complicit in a violation of Human Rights.”

[26] See tax returns, p. 18 of the 2013 tax return, p. 17 of 2009 return.

[27] start here, click 2015 tax return, see p. 26.

[28] Foundation Center, p. 36, and Foundation Center, p. 30.

[29] In September 2018, the AFT 2121 leadership claimed “membership has grown to an all-time high of 88%!” However, unless they raise the size of the deduction for dues or the pay of members increases, the union will be receiving less revenue. AFT 2121 Members in Action.

[30] Our concerns about class cuts continue.

[31] I taught at Chabot College for four terms. Towards the end of my time teaching there, I discussed with my department chair my future work prospects. With great indifference, she told me that there is no work. And this is a person who had a copy of the Marxist classic, Monopoly Capital, prominently displayed on her bookshelf!

______________________________________________________________________________

Appendix #1

Pay Lags Behind Increases in the Cost of Living

Below are the California State Chancellor’s salary figures for faculty members working in three community colleges in the San Francisco Bay Area that are represented by AFT locals. Average pay in 2007, before the Great Recession, is compared with 2017. According to The Association of Bay Area Governments, the cost of living increased by 27.5% from 2007 to 2017.

Cite: Association of Bay Area Governments shows CPI from 2007-2017 going from 216 to 275.4

Full Time Faculty Average Salaries 2007 2017 Percent increase

City College of San Francisco $80,757 $93,178 15.4%

San Mateo District $81,084 $103,047 27.1%

Marin District $87,659 $103,059 17.6%

Sources: http://employeedata.cccco.edu/avg_salary_17.pdf pages 4-5

http://employeedata.cccco.edu/avg_salary_07.pdf pages 4-5

Part-Time Faculty Average Salaries 2007 2017 Percent increase

City College of San Francisco $88.71/hour* $104.95 18.3%

San Mateo District $84.94 $92.47 8.9%

Marin District $93.63 $115.61** 23.5%

*The hourly pay is only for time in the classroom. One is not paid for preparation time or grading time. At CCSF, the limit is for 10 hours of class time/week.

**This is for 2016 since the 2017 figure of $27.30 makes no sense.

Source: http://employeedata.cccco.edu/avg_hourly_17.pdf For Marin substitute 16 for 17. Pages 7-8 http://employeedata.cccco.edu/avg_hourly_07.pdf pages 5-6

According to these figures, full-timers in only the San Mateo district have experienced salary increases that appear to have kept up with increases in the cost of living. However, increases in pay have been undercut by additional deductions and givebacks. In 2017, all full-time faculty and others in the CALSTRS defined pension plan were subject to an increase in the deduction from their pay for their pension. For most, it went from 8% to 10.25% and is similar to a 2.25% pay-cut. Many may also be having more money deducted from their pay to cover the portion of medical insurance paid by employees. CCSF faculty have experienced other increased deductions from their pay including an increase in union dues of ¼% and, for full-timers, an increase in contributions to their retiree medical benefits of at least 1%.

Appendix #2

Pay of Part-timers at CCSF is Much Less than what Union Leaders Claim

The pay of faculty at CCSF is based on one’s placement on the pay scale. There are columns based on one’s education level with step increases that award one with higher pay the longer one teaches at the college. Part-timers looking up their pay find their column and step in the full-time pay scale and multiply it by 86% (or 100% if a part-time counselor or librarian.) They then multiply that amount by their load–the percent they work (which cannot be more than 67% of the work of a full-timer.)

For example, if the annual pay of a full-timer is $80,000, the pay of a part-time teacher in the same column and on the same step who teaches 60% of a full load is $80,000 times 86% (the pro-rata rate) times 60% (the load) which comes to $41,280.

Using the July 2018-June 2019 salary schedule for part-time and full-time teachers illustrates how much each is paid and how the pay of most part-timers is less than 86% of a full-timer. This example is based on teachers who are in column F + 15 who have a BA degree plus 45 units and a Master’s Degree. Step 1 represents the pay for each in their first year of work (assuming one is not initially placed on a higher step which, until recently, was only available to newly hired full-timers with experience.) Step 10 is the pay of a full-timer starting their 10th year of work. The part-timer who has worked 10 years would be at step 5. The part-timer who has worked 20 years would be at step 10 while the full-timer is at step 20.

Annual Salaries

FT pay Part-timers Part-timer teachers’ actual percent

equivalent pay of full-timers pay

at 100% load

Year 1 $62,980 $54,163 86%

Both on Step 1

Year 10 $87,010 $63,348 72.8%

On step 10 On step 5

Year 20 $105,700 $74,829 70.8%

On step 20 On Step 10

Gap in pay/class for each teaching one 3 unit class, at a 10% load

FT pay PT pay Difference

Year 1 $6,298 $5,416 $872

Year 10 $8,701 $6,335 $2,366

Year 20 $10,570 $7,483 $3,087

Full-time pay scale

Full time salary schedules 3 years (1)

Part-time pay scale

http://www.aft2121.org/wp-content/uploads/86-Pro-rata-pay-scales-3-years-2.pdf

Appendix #3

Pay Gap between the lowest and highest paid full-timers at CCSF increased under new contract

Example 1 Column F

-BA plus 30 units with an MA

Pay of Full-Time Faculty Members

2017 2018 Pay increase

Old contract New Contract Under new contract

At Step 1 $58,499 $61,200 $2,701

Highest Step $101,217 $111,930 $10,713

Example 2 Column F Plus 45

-BA plus 75 units with MA

At Step 1 $62,507 $66,540 $4,033

Highest step $105,222 $117,270 $12,048

__________________

–Increased gap in pay of faculty member on step one of column F compared to member in Column F Plus 45 at the highest step

Gap

Gap in 2018 $117,270 minus $61,200 $56,070

Gap in 2017 $105,222 minus $58,499 $46,723

Increase in Pay Gap under new contract $9,347

Those with the most seniority and PhDs received the biggest pay increases.

links full-time pay in 2018-19 under the agreement

full-time pay for 2017-18

The troops gathering on the borders between Venezuela and Brazil and Colombia are no less threatening to Venezuela because they claim to be protecting a ‘humanitarian convoy’. And Richard Branson’s concert simply provides another cover to conceal the real purposes behind this so-called aid. Donald Trump, and his neoconservative aides John Bolton and Mike Pompeo, have no concern for the welfare of Venezuela’s people – any more than their predecessors did in Libya, Rwanda and countless other examples of fraudulent mercy missions that were concerned only with a search for power and control. How credible can this operation to ‘rescue’ Venezuela be when it coincides with a demand to spend six billion dollars on a wall to deter impoverished immigrants from travelling north in search of work?

The troops gathering on the borders between Venezuela and Brazil and Colombia are no less threatening to Venezuela because they claim to be protecting a ‘humanitarian convoy’. And Richard Branson’s concert simply provides another cover to conceal the real purposes behind this so-called aid. Donald Trump, and his neoconservative aides John Bolton and Mike Pompeo, have no concern for the welfare of Venezuela’s people – any more than their predecessors did in Libya, Rwanda and countless other examples of fraudulent mercy missions that were concerned only with a search for power and control. How credible can this operation to ‘rescue’ Venezuela be when it coincides with a demand to spend six billion dollars on a wall to deter impoverished immigrants from travelling north in search of work?

One of the great challenges to redressing the split between Democratic Party avoiding and Democratic Party engaging socialists, is how to productively deal with a beguiling strategic predilection of the party avoiders. That predilection is to assail the Democrats as socialist spoilers; and while their arguments are not necessarily wrong, the ways they prove them divert many from facing the unity-encumbering dynamics of their left formation-building strategies.

One of the great challenges to redressing the split between Democratic Party avoiding and Democratic Party engaging socialists, is how to productively deal with a beguiling strategic predilection of the party avoiders. That predilection is to assail the Democrats as socialist spoilers; and while their arguments are not necessarily wrong, the ways they prove them divert many from facing the unity-encumbering dynamics of their left formation-building strategies.

Well, it’s happened: Senator Bernie Sanders has declared his candidacy for the 2020 Presidential nomination of the Democratic Party. Seeing a historic opportunity,

Well, it’s happened: Senator Bernie Sanders has declared his candidacy for the 2020 Presidential nomination of the Democratic Party. Seeing a historic opportunity,

Ooh the harder they come

Ooh the harder they come

Sudan. The endless lines outside bakeries and gas stations suggest an almost willful naiveté about the dire economic and political situation. The Kafkaesque bureaucratic system requires an element of nepotism to vitalize it into animation. The lack of cash in banks, and the depreciation of the local currency force the people to convert and conserve money. The increased taxes on the average citizen and the tax cuts for those associated with the government produce distrust and disgust directed towards the state. The secret services arbitrarily arrest of persons who display even the slightest antipathy towards government doctrine and use gulag-like hidden torture prisons. All these phenomena, and others, have converged, and the implosion of this concoction manifests as a wave of zealous, righteous indignation that overwhelm every Sudanese person. There is a rumble in the atmosphere that can be felt all over the country. The echo of gun shots and tear gas booms ripple to the furthest corners of Sudan. From the naming and shaming of secret service officials on social media, to clashes between citizen and government, it’s a full-blown revolution!

Sudan. The endless lines outside bakeries and gas stations suggest an almost willful naiveté about the dire economic and political situation. The Kafkaesque bureaucratic system requires an element of nepotism to vitalize it into animation. The lack of cash in banks, and the depreciation of the local currency force the people to convert and conserve money. The increased taxes on the average citizen and the tax cuts for those associated with the government produce distrust and disgust directed towards the state. The secret services arbitrarily arrest of persons who display even the slightest antipathy towards government doctrine and use gulag-like hidden torture prisons. All these phenomena, and others, have converged, and the implosion of this concoction manifests as a wave of zealous, righteous indignation that overwhelm every Sudanese person. There is a rumble in the atmosphere that can be felt all over the country. The echo of gun shots and tear gas booms ripple to the furthest corners of Sudan. From the naming and shaming of secret service officials on social media, to clashes between citizen and government, it’s a full-blown revolution!

In his scathing, Sturm und Drang takedown of the 1851 French dictatorial coup, The 18th Brumaire of Louis Napoléon, Marx remarks that history repeats twice: “the first time as tragedy, the second time as farce.” Thus when Luther pit himself against the Catholic establishment, he put on, according to Marx, “the mask of the Apostle Paul.” Likewise, the French Revolution of 1789-1814 “draped itself alternately in the guise of the Roman Republic and the Roman Empire.” And to Marx’s chagrin, the latter guise, in particular, enjoyed a revival under Louis Napoléon Bonaparte, who drew on it relentlessly to rationalize his retconning of the Napoléonic legacy.

In his scathing, Sturm und Drang takedown of the 1851 French dictatorial coup, The 18th Brumaire of Louis Napoléon, Marx remarks that history repeats twice: “the first time as tragedy, the second time as farce.” Thus when Luther pit himself against the Catholic establishment, he put on, according to Marx, “the mask of the Apostle Paul.” Likewise, the French Revolution of 1789-1814 “draped itself alternately in the guise of the Roman Republic and the Roman Empire.” And to Marx’s chagrin, the latter guise, in particular, enjoyed a revival under Louis Napoléon Bonaparte, who drew on it relentlessly to rationalize his retconning of the Napoléonic legacy.

There is something politically familiar in Cedric Johnson’s two essays in Catalyst (Vol. 1, No. 1, Spring 2017) and

There is something politically familiar in Cedric Johnson’s two essays in Catalyst (Vol. 1, No. 1, Spring 2017) and

The New York Times (1/22/19) reported on a bleak letter by the billionaire investor Seth Klarman that was circulated at the World Economic Forum in Davos. The letter warns about the coming financial crisis amid increased levels of social conflict.

The New York Times (1/22/19) reported on a bleak letter by the billionaire investor Seth Klarman that was circulated at the World Economic Forum in Davos. The letter warns about the coming financial crisis amid increased levels of social conflict.

Barely five years ago, if you asked someone where a new U.S. socialist movement might appear, I would wager that nearly no one would have said with the Democratic Socialists of America (DSA). Before 2016, DSA’s profile was largely that of a paper organization—a kind of socialist AARP that made it an unlikely candidate for a revitalized left. And yet, DSA is now an organization of over 55,000 members.

Barely five years ago, if you asked someone where a new U.S. socialist movement might appear, I would wager that nearly no one would have said with the Democratic Socialists of America (DSA). Before 2016, DSA’s profile was largely that of a paper organization—a kind of socialist AARP that made it an unlikely candidate for a revitalized left. And yet, DSA is now an organization of over 55,000 members.

What is Post-Modern Conservatism: Essays on Our Hugely Tremendous Times

What is Post-Modern Conservatism: Essays on Our Hugely Tremendous Times

Venezuela has made headlines in the last few weeks, as Venezuelan opposition leader and National Assembly head Juan Guaidó has declared himself interim President, throwing the country into turmoil. Current President, Nicolás Maduro has called the effort a coup. Meanwhile, thousands of people have taken to the streets on both sides, with

Venezuela has made headlines in the last few weeks, as Venezuelan opposition leader and National Assembly head Juan Guaidó has declared himself interim President, throwing the country into turmoil. Current President, Nicolás Maduro has called the effort a coup. Meanwhile, thousands of people have taken to the streets on both sides, with

The vicious, dirty – and bipartisan – smear campaign against the first two Muslim women in the U.S. Congress, Ilhan Omar (MN) and Rashida Tlaib (MI), is just beginning. No one should imagine that Rep. Omar’s dignified apology for her tweets about the Israel lobby, which have been willfully twisted to accuse her of “anti-Semitic tropes,” will put an end to the attacks on her – or that Rep. Tlaib’s calling Donald Trump a “motherf****r” is what anyone is really upset about.

The vicious, dirty – and bipartisan – smear campaign against the first two Muslim women in the U.S. Congress, Ilhan Omar (MN) and Rashida Tlaib (MI), is just beginning. No one should imagine that Rep. Omar’s dignified apology for her tweets about the Israel lobby, which have been willfully twisted to accuse her of “anti-Semitic tropes,” will put an end to the attacks on her – or that Rep. Tlaib’s calling Donald Trump a “motherf****r” is what anyone is really upset about.

On finishing a particularly annoying novel, a good friend of mine once gasped in exasperation: ‘The author’s fingerprints are all over this.’ I can’t say I remember now the book he was talking about, but the phrase has been with me ever since, because it encapsulates certain writers so perfectly.

On finishing a particularly annoying novel, a good friend of mine once gasped in exasperation: ‘The author’s fingerprints are all over this.’ I can’t say I remember now the book he was talking about, but the phrase has been with me ever since, because it encapsulates certain writers so perfectly.

Socialists must organize a national movement against Trump’s national emergency.

Socialists must organize a national movement against Trump’s national emergency.

Tulsi Gabbard is getting a pass from people who should know better, first from

Tulsi Gabbard is getting a pass from people who should know better, first from

On Tues, Feb. 5, as the Macron government pushed harsh repressive laws against demonstrators through the National Assembly, the Yellow Vests joined with France’s unions for the first time in a day-long, nation-wide “General Strike.”

On Tues, Feb. 5, as the Macron government pushed harsh repressive laws against demonstrators through the National Assembly, the Yellow Vests joined with France’s unions for the first time in a day-long, nation-wide “General Strike.”

A message put forward in our capitalist society is if people get a college education, they will likely get better-paying jobs. However, there are many with college degrees who endure insecure working conditions and are poorly compensated. They include part-time teachers in institutions of higher education, most of whom have advanced degrees.

A message put forward in our capitalist society is if people get a college education, they will likely get better-paying jobs. However, there are many with college degrees who endure insecure working conditions and are poorly compensated. They include part-time teachers in institutions of higher education, most of whom have advanced degrees.