Viewed from the perspective of geological history, our current climatic and economic conditions are unusual. For most of the last 60 million years, the climate has been wildly unstable. It was only 10,000 years ago that it settled into its current stable state, and within this period that the Holocene emerged, during which human societies shifted their relationship with nature though agriculture, and then creating complex settled socio-economic forms, including capitalism.

Viewed from the perspective of geological history, our current climatic and economic conditions are unusual. For most of the last 60 million years, the climate has been wildly unstable. It was only 10,000 years ago that it settled into its current stable state, and within this period that the Holocene emerged, during which human societies shifted their relationship with nature though agriculture, and then creating complex settled socio-economic forms, including capitalism.

Despite its omnipresence today, capitalism itself is very young. But it has its roots in that stabilisation of the climate and the subsequent development of agriculture. Fully-fledged global capitalism has been with us for no more than 300 years. In the 4.5 billion year history of the earth, capitalism is a brief moment within the blink of an eye that is human existence.

But this brief moment is a global force. It is capitalism that has placed us on a path to leave the stable climate of the Holocene. Thanks to capitalist development, the earth is currently 0.8 of a degree warmer than the pre-industrial average. Without overthrowing capitalism, we are likely to warm the earth to levels that humans as a species have never lived with.

This should terrify socialists. As I will argue here, the environmental system and the economy have co-evolved. The economy is dependent on the environment. Once we leave the stable climatic conditions of the last 10,000 years, we have very little guidance on how to build a socio-economic system that works. There is no particular reason to think the systems we have developed in one set of environmental conditions will flourish in another. There is also no reason to believe that such conditions provide fertile ground for the development of a more compassionate or humane socio-economic system.

If we want to stand a chance of building socialism in the near future, we must become eco-socialists and stop catastrophic climate change now. At the same time, to stop catastrophic climate change, environmentalists must also become eco-socialists. The dynamics that drive climate change are core to capitalism. Serious action on climate change will necessarily amount to the first steps of a programme to end capitalism.

The economy, the energy system, and the environment: co-evolutionary systems.

The economy, the energy system and the environment have evolved together. They draw on one another, passing materials between them and absorbing one another’s wastes. All economic activity ultimately rests on the transformation of material resources. These must be drawn from the environment and then worked by labour. Marx makes this interdependency explicit:

The use values… i.e. the bodies of commodities, are combinations of two elements–matter and labour. If we take away the useful labour expended upon them, a material substratum is always left, which is furnished by Nature.1

Marx uses the example of linen–which is produced by workers (labour) who transform the fibres of the flax plant (environment). But this interdependency also holds true for more modern commodities. For example, the servers that host the files for music streaming services are made of up various minerals and metals that have been rearranged by labour.

An additional interdependency comes in the form of energy. At every stage of the production of a commodity, energy is being used to transform matter from one form to another. Metals are heated, melted and transformed into iPhones. Cotton is grown, harvested, woven, and dyed to make scrubs worn by surgeons. The energy used in these processes cannot be created. It can only be transformed.

All energy used in the economy is entropic: it comes from a repurposing of energy found in the earth system, and exacting it in return for a cost. Coal is dug from the ground and burnt, solar energy is captured by photovoltaics, or in plants that we cook and eat. The energy system which enables economic activity is entirely dependent on the environment.

We see here how the environment influences the economy. The economy is the process of transforming materials extracted from the environment by repurposing energy flows from the earth system. The result of this, is, to quote Marx’s citation of the economist William Petty, that when it comes to material wealth, “labour is its father and the earth its mother”.2 But at the same time, the environment and the energy system are shaped by the economy. The priorities of the economic system determine the valuation of each element, as well as which materials are extracted, changing the composition, look and dynamics of the environment.

The practice of extraction itself is not exclusive to capitalism. Agricultural practices that pre-date capitalism have reshaped our landscapes. Take sheep farming, for example.3 Heavy grazing tends to change the biological make up of heathland. Eventually, heathland may lose all of its herbs and woody species and become grassland. As grasses can survive for longer as the sheep eat them than woody plants and herbs, the transition from heathland to grassland can make conditions more favourable for sheep grazing as the sheep have more to eat. This is less helpful for bird life, as the grasses are a poor habitat substitute and the sheep compete with birds for certain types of fruit, and reduce the availability of various insects. Through pastoral grazing economic activity has transformed former heathland landscapes.

Climate change is another example of the co-evolution of the economy and the environment, but this time, one specific to capitalism. As we will see, the two are inextricably linked. Without fossil fuel deposits, capitalism could not have become the dominant force it is today. Similarly, without capitalism, fossil fuels may never have become the backbone of the economy.

Coal, the great divergence and the origins of capitalism

Between the mid 1500s and 1900, there was an explosion of coal use in England. On average, English coal use more than doubled every half century during this time period. By 1900 coal represented 92% of English energy use and was providing 25 times more energy than all energy sources combined had in the mid 1500s.

Over this time period the English economy also grew rapidly. For mainstream economic historians, the period from 1700 onwards marks the start of ‘the great divergence’. England began the industrial revolution and its economy took off, becoming much larger than other economies that had until that point been a similar size.

It is not a coincidence that coal use and economic growth expanded simultaneously. Coal is a high quality fuel. It offers a much greater amount of energy out for every unit of energy required to produce it than wood, for example. Consequently, it enables more work to be done–more materials transformed – than muscle power alone, or even wood or water–the dominant fuel sources in the nascent English industrial economy.

But the geographical distribution of coal is not, by itself, enough to explain English economic growth or the ‘great divergence’. In 1700, China had widespread domestic coal use, just like England. And until 1700 China had a similar sized economy, with similar levels of market activity. But neither Chinese coal use nor the Chinese economy grew exponentially in the way that England’s did.

The difference was the consolidation of capitalist social relations in England. We can locate the pressures that lead to capitalism, and the capitalist exploitation of coal, in the agrarian economy of 1500s England. As these pressures grew, they drove coal use and economic growth in England. Though pre-capitalist China was incredibly well-developed, had an extensive use of wage-labour within markets, it never became dominated by proto-capitalists, and so did not develop the same systematic pressures. Coal use and the economy, subsequently, did not see the same qualitative expansion.

Political Marxism and the Fossil Economy

Archetypical of the Political Marxist approach to modes of production, Ellen Meiksens Wood argues that a capitalist economy is one where a majority of people depend on the market to meet their basic needs.4 This distinguishes capitalism from feudalism, in which there is a large peasant class largely self-sufficient in terms of basic needs, and in which the more powerful classes depend not on market power to support their consumption, but on military and extra-economic power. Wood further distinguishes between the form of markets under capitalism and those that characterise pre-capitalist economies. She argues that markets originally functioned and made profit by providing a means of getting goods that could only be produced in one part of the world to other parts, where those goods could not be produced. She goes on to argue that capitalist markets operate differently: profit here is achieved by reducing costs and improving productivity.

Though substantially debated, this approach was developed by Wood (alongside Richard Brenner) as a reaction to what she saw as ahistorical explanations of the role of markets in the development of capitalism—particular the claim, coming from Adam Smith, that capitalism is “…the necessary, though very slow and gradual consequence of a certain propensity in human nature…the propensity to truck, barter, and exchange one thing for another.”5Against this, Wood argues that capitalism began in England because of its unique constellation of social conditions.

In her landmark work The Origin of Capitalism,6 Wood argues that capitalism could only have begun in agrarian England. Unlike other nations with similarly sized economies, England had the unique combination of a large national market, substantial numbers of tenant farmers (as opposed to peasants, tied to the land by social convention), and highly centralised state power. These three components come together to create a transition to a market dominated economy. Highly centralised state power took political and military power away from land owners. So unlike in Holland, for example, the primary way for landowners to exploit the surplus of their workers was through market means rather than direct coercion. This was possible because of the existence of the large national market in which they could sell goods for a profit, and because of the existence of tenant farmers, which meant they could remove unproductive farmers from their land.

It is the development of capitalist markets, as Wood describes them, that creates the conditions for fossil fuel exploitation. Capitalist markets, like all economic systems, turn on the necessity of using economic tools to extract surplus. This dynamic creates capitalism’s drives to reinvest in productivity growth and to discipline the workforce in order to increase output. Because landowners were now dependent on the market for their own livelihoods, they tried to reduce costs and maximise outputs. This fundamental change in the nature of production created a system in which the ability of energy to do extra work became very attractive. Although Wood never directly discusses energy, her work has influenced Andreas Malm, whose Fossil Capital7 does pick up the energy question.8

Malm argues that under the conditions of capitalism, coal came to be a tool of social control. Coal centralises production, bringing workers under one roof. This serves the dual purpose of making them less able to embezzle from their employers, allowing improved scales of production, and also enabling employers to more easily regulate the times of work and levels of production. In addition, coal—alongside the machinery it allows—improves productivity: by giving them a greater source of energy than food and their muscles alone, coal increases the amount of output that can be produced by workers.

Only in England did the capitalist class benefit from these features of coal. Economic structures elsewhere followed fundamentally different logics that did not reward productivity and output growth. Though markets existed outside of England, central power and surplus was derived from military and political power, and only peripherally from economic power. Consequently, although productivity increases may have occurred by chance, societies were not systematically driven by the need to continuously produce more, or to do so more productively. As Debeir et al. put it, Chinese coal use:

…did not create new social needs, did not constantly push the borders of its own market outwards…proto-industrialisation and economic growth were remarkable achievements but failed to generate an accelerated division of labour.9

To understand this more fully, let us now examine the nature of capitalist markets in more detail.

Capitalist Markets and the Pressures to Grow

The ecological economists Tim Jackson and Peter Victor call the above dynamic the “productivity trap”.10 It occurs because, under capitalism, workers must be able to sell their labour to be able to obtain a decent standard of living. Capitalists depend on market power for their profits and therefore constantly reinvest in productivity gains. Productivity gains mean fewer workers are needed to produce a unit of output. So if output stops growing, employment will fall. This creates a legitimate desire amongst workers for more growth, and gives governments a mandate to do everything they can to expand economic activity.

Moreover, this ‘productivity trap’ is self-reinforcing. The expansion of markets drives the division of labour. Adam Smith argued that as workers become more specialised, they are better able to improve the production processes they’re engaged with. And at a higher level of specialisation you develop whole classes of workers whose job is purely to make production more efficient. In this way market expansion itself leads to productivity gains. But as people become more specialised this means that they come to depend on markets to get more and more of their goods—because (to use a personal example) people who sit in offices reading long-dead economists for a living don’t spend much time growing food, sewing clothes, or saving lives. So the expansion of markets creates both the conditions for further growth and the need for it.

We also need to talk about consumer capitalism. Innovations leading to productivity gains do not in themselves create a market for the greater volume of goods produced. This means that capitalism must alter consumption as well as production. Today, this increasingly involves the stimulation and artifical creation of consumer needs and desires by the capitalist class—who need us to keep consuming if they are to continue earning profits. William Morris argued that in order to get and maintain profits, capitalists must sell a “mountain of rubbish…things which everybody knows are of no use”. In order to create demand for these useless goods, capitalists stirred up:

a strange feverish desire for petty excitement, the outward token of which is known by the conventional name of fashion—a strange monster born of the vacancy of the lives of rich people

A substantial body of more modern work suggests that current society encourages the idea that consumption is the path to self-betterment. Psychologist Philip Cushman argues that the dominant present configuration of the “self” is as an empty vessel that requires filling up with consumer goods.11 The emptiness, he argues, comes from a lack of community, tradition, and shared meaning. These are not things that will be solved through consumption. Under consumer capitalism, there comes a collective inability to imagine social and personal change except through consumption. As a result, even ‘radical’ leftist futures tend to revolve around ever increasing levels of material consumption, rather than imagining new ways to live that prioritise our need for community and purpose beyond consumption.

No decarbonisation under capitalism

Because of the structural drivers towards growth that we see under capitalism, it is extremely unlikely that capitalism can avoid catastrophic climate change. The structural drive for growth means that efforts to reduce carbon emissions will be overwhelmed by the expansion of economic activity. This is controversial to most mainstream environmentalists (and to many socialists). But it is the clear experience of the history of capitalism.

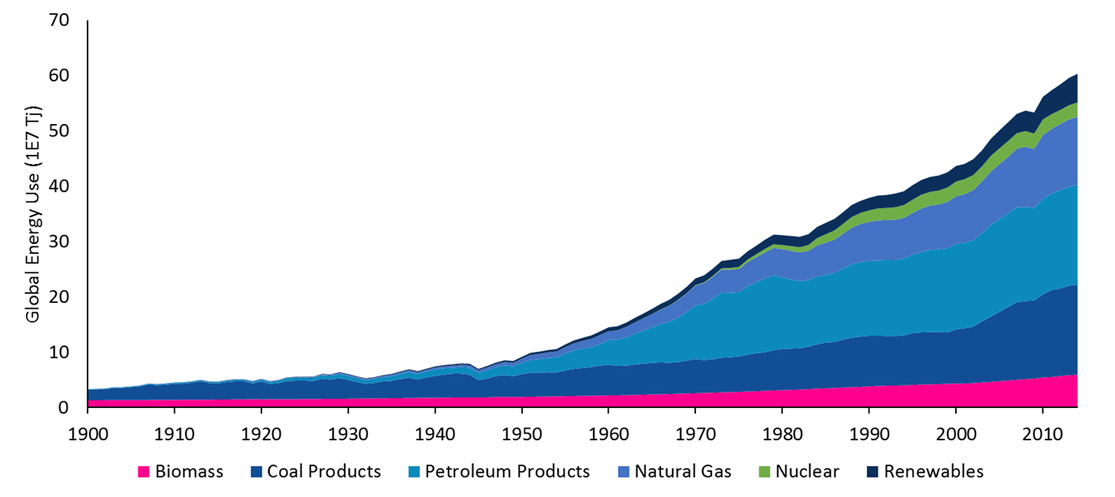

To date, resources have not been conserved under capitalism. Rather when we become more efficient or find new resources, this frees up resources that are used by other parts of the capitalist machine. This explains why, for example, renewable energy and nuclear power remain only a small part of the global energy system (Figure 2). Under capitalism, low-carbon energy sources have grown but they have not replaced fossil fuel at any meaningful scale. Instead low-carbon energy is simply another energy pot available to fuel growth in economic activity in order to generate profits.

Figure 2 Global Primary Energy Use by type, 1900-2014. Source: Author’s own calculations based on data from De Stercke, 2014.

The same is also true of energy efficiency gains. Energy efficiency can be a key contributor for decarbonising the global economy. But only if it is coupled to a plan to limit the size of the economy. Under capitalism, energy efficiency measures actually drive economic growth. This happens for the same reason renewable energy doesn’t lead to decarbonisation. Energy efficiency improves productivity and reduces costs. In this way it reinforces capitalist growth imperatives, driving the expansion of the economy which requires more energy to be used overall.

This is also why progressive action on climate change will undermine capitalism. We will only successfully avoid catastrophic climate change if we are able to break the dominance of the market, and break the social imaginary that ineffectually ties fulfilment to consumption.

So, where do we go from here?

The economy, the energy system, and the environment are all inextricably linked. Combining ecological economics and Political Marxism, I have set out a framework in which climate change can be seen not only as a consequence of capitalism but as fundamental to it. Widespread fossil fuel use was enabled by, and necessary for, the capitalist dynamics of productivity growth and expansion. Climate change is a feature, not a bug of capitalism.

To avoid catastrophic climate change, we have to break the expansionary cycle of the economy. Otherwise technological improvements, renewable energy, and energy efficiency gains will do nothing but add to the stock of ways that capitalists grow the economy and their profits. Likewise carbon taxes and other market mechanisms will simply reinforce the core dynamics of the market and any positive effects will be overwhelmed by growth. Growth will increase energy use, including fossil fuel use. This will plunge us into a world that we do not know how to live in. It is likely that ‘hothouse earth’ will eventually destroy capitalism. But not before destroying the livelihoods of millions through extreme weather, greater incidence of disease, and ecological breakdown. There is no reason to believe this will lead to a better future.

Breaking the expansionary cycle of the economy in a just way requires rolling back markets. We must instead use commons, household, and state-based production as the principal means of meeting the collective needs of society. Only in this way can we break the societal drive for productivity growth and expansion. There is nothing inherently more sustainable in non-market forms of production (all economic activity uses energy), but these systems lack the expansionary drive of markets. Consequently, energy efficiency gains and new technologies can be used to replace fossil fuels rather than add to them.

This transition has the potential to be hopeful, a chance to build a more humane system. This system will be materially poorer than today’s society. But this is not ‘eco-austerity’. Much of the energy we use today is in producing goods that we do not need, that do not fulfil our needs. Richard Seymour articulates this in the context of the labour theory of value:

The overproduction of ‘stuff’ is largely achieved by making a costly withdrawal from the worker’s body, a form of life-impoverishing austerity. And a great deal of that ‘stuff’ is not for workers’ consumption, but rather, where it is not consumed as profit and dividends, is dead labour whose main effect is to achieve a further extraction of labour. We might think of energy conservation as class self-defence.

Put another way, consumption is an ineffective way of building a good life. Collectively limiting our consumption could open a path to a better economic system.

There are links between such a program and other radical leftist programs for change. Freedom from the market and repurposing of production along the lines of social need rather than profit are central to the post-work movement.12 But this movement lacks a critique of consumerism, and its analysis of capitalism fails to engage rigorously with insights from ecological economics. Visions of mass space flight continue the fantasy that consumption can fulfil us, and rely on the notion of continued expansion of output and energy use. It is unclear why those who advocate ‘fully automated luxury communism’ (for example) believe that a political programme whose key appeal lies in having more stuff will find itself able to break free from the expansionary cycle that lies at the heart of the ecological catastrophe. If the promise is more mass consumption, doing away with the most reliable and efficient energy sources to which we have access will be a hard political sell. There can be no avoiding growth in fossil fuel use under capitalism. But this does not mean that anti-capitalist programmes are all equally good solutions. The route forward is to embrace these radical impulses, but critique their obsession with consumption, and highlight the destructive dynamics they share with capitalism.

This marks out the terrain for political struggle. Socialists must engage mainstream environmentalists and work with them. We have a common foe in the big capital of the fossil industry. Many environmentalists are critical of the economy as it is, but lack a full analysis of its mechanics. Extinction Rebellion is a key example of this: a critical yet ‘apolitical’ movement. Yet they offer perhaps our best hope for building institutions that give us community, autonomy, and purpose, and for breaking with the expansionary capitalist fossil economy.

- Marx, Karl. (1856) 1990. Capital: A Critique of Political Economy Vol. 1. Translated by Ben Fowkes. London: Penguin, p.133 ↩

- ibid. p.134 ↩

- Ross, L.C., Austrheim, G., Asheim, LJ. et al. ‘Sheep grazing in the North Atlantic region: A long-term perspective on environmental sustainability’. Ambio (2016) 45(5):551-566. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13280-016-0771-z ↩

- Wood, Ellen Meiksens. 2017. The Origin of Capitalism: A Longer View. London: Verso. ↩

- Smith, Adam. (1776) 1976. An Enquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, p.17. ↩

- Wood (2017). ↩

- Malm, Andreas. 2016. Fossil Capital: The Rise of Steam Power and the Roots of Global Warming. London: Verso. ↩

- ibid. p.258, 263 ↩

- Deléage, Jean-Paul, Jean-Claude Debeir, Daniel Hémery. 1991. In the Servitude of Power: Energy and Civilisation Through the Ages. London: Zed Books, p.59 ↩

- Jackson, Tim and Peter Victor. ‘Productivity and work in the ‘green economy’: Some theoretical reflections and empirical tests’. Environmental Innovation and Societal Transitions (June 2011) 1(1):101-108. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eist.2011.04.005 ↩

- Cushman, Philip. ‘Why the Self is Empty: Toward a Historically Situated Psychology’. American Psychologist (1990) 45(5):599-611. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.45.5.599. ↩

- Weeks, Kathi. 2011. The Problem with Work: Feminism, Marxism, Anti-Work Politics and Post-Work Imaginaries. Durham, NC: Duke University Press. ↩

Originally posted at New Socialist.

We have been slimed. An article by Ben Norton and Max Blumenthal on the recent Socialism 2019 Conference — which appears on their rancid website, The GrayZone, and is apparently being widely circulated — is a scurrilous attack not only on the conference itself, but also on one of our editors, Dan La Botz, and indeed on the entire political outlook of socialism from below, which has always been the defining perspective of our journal.

We have been slimed. An article by Ben Norton and Max Blumenthal on the recent Socialism 2019 Conference — which appears on their rancid website, The GrayZone, and is apparently being widely circulated — is a scurrilous attack not only on the conference itself, but also on one of our editors, Dan La Botz, and indeed on the entire political outlook of socialism from below, which has always been the defining perspective of our journal.

A recent article in the GrayZone viciously slanders the Democratic Socialists of America (DSA), Jacobin magazine, and Haymarket books, accusing these sponsors of the Socialism conference in Chicago last weekend of hosting paid government agents engaged in attempts at regime change in several countries. In addition to those three organizations, the longtime leftist journal on Latin America NACLA and the Brooklyn-based Marxist Education Project are also similarly defamed. And I myself am particularly singled out, with the suggestion that I am complicit in some Republican plot to overthrow the government of Nicaragua.

A recent article in the GrayZone viciously slanders the Democratic Socialists of America (DSA), Jacobin magazine, and Haymarket books, accusing these sponsors of the Socialism conference in Chicago last weekend of hosting paid government agents engaged in attempts at regime change in several countries. In addition to those three organizations, the longtime leftist journal on Latin America NACLA and the Brooklyn-based Marxist Education Project are also similarly defamed. And I myself am particularly singled out, with the suggestion that I am complicit in some Republican plot to overthrow the government of Nicaragua.

The Alliance of Middle Eastern and North African Socialists is hosting a panel to discuss these questions:

The Alliance of Middle Eastern and North African Socialists is hosting a panel to discuss these questions:

If you’ve had the displeasure of tuning in to Fox News at any point over the last ten years, you’ll know that they’ve played no small part in turning the U.S. into a right-wing hellscape. A place where male political analysts scream over each other about women’s reproductive organs and companies can price-gauge lifesaving medication at the expense of the very worst-off in society.

If you’ve had the displeasure of tuning in to Fox News at any point over the last ten years, you’ll know that they’ve played no small part in turning the U.S. into a right-wing hellscape. A place where male political analysts scream over each other about women’s reproductive organs and companies can price-gauge lifesaving medication at the expense of the very worst-off in society.

The 2019 Convention for Democratic Socialists of America (DSA) is fast approaching, and there is a lot to sort out. The Convention will debate and vote on the approved resolutions and constitution/bylaw changes and elect a new sixteen (16) person leadership body, the National Political Committee (NPC). Resolutions will commit DSA to political positions, organizational changes and/or specific projects or courses of action. All of these will have to take into consideration the organization’s budget, staff and member capacity.

The 2019 Convention for Democratic Socialists of America (DSA) is fast approaching, and there is a lot to sort out. The Convention will debate and vote on the approved resolutions and constitution/bylaw changes and elect a new sixteen (16) person leadership body, the National Political Committee (NPC). Resolutions will commit DSA to political positions, organizational changes and/or specific projects or courses of action. All of these will have to take into consideration the organization’s budget, staff and member capacity.

In Istanbul the joy was expressed along the two extremes of the Bosphorus, from the district of Besiktas to Kadiköy, through Sisli, Esenler, Beylikdüzü. Klaxons blowing, songs, flags being waved in cars running the avenues — the city has voted for a change and with hope they celebrated on the night of June 23. All over there were sellers in the street with scarves, flags and badges with winner Ekrem İmamoğlu’s slogan « Everything will be alright! ».

In Istanbul the joy was expressed along the two extremes of the Bosphorus, from the district of Besiktas to Kadiköy, through Sisli, Esenler, Beylikdüzü. Klaxons blowing, songs, flags being waved in cars running the avenues — the city has voted for a change and with hope they celebrated on the night of June 23. All over there were sellers in the street with scarves, flags and badges with winner Ekrem İmamoğlu’s slogan « Everything will be alright! ».

Bhaskar Sunkara, the young, left, entrepreneurial genius who founded and publishes Jacobin, has written a book,

Bhaskar Sunkara, the young, left, entrepreneurial genius who founded and publishes Jacobin, has written a book,  Reviewing a Friend’s Book

Reviewing a Friend’s Book

Democratic Socialists of America emphatically and unreservedly opposes a U.S. war on Iran. It would be another “war of choice,” just like the Iraq War of 2003, and would likely be just as colossal a humanitarian disaster.

Democratic Socialists of America emphatically and unreservedly opposes a U.S. war on Iran. It would be another “war of choice,” just like the Iraq War of 2003, and would likely be just as colossal a humanitarian disaster.

Since the outbreak of the Sudanese and Algerian uprisings in early 2019, there has been much hope that these developments would move beyond the many barriers that destroyed the revolutionary process that began in the Middle East and North Africa in 2011.

Since the outbreak of the Sudanese and Algerian uprisings in early 2019, there has been much hope that these developments would move beyond the many barriers that destroyed the revolutionary process that began in the Middle East and North Africa in 2011.

Give Bernie Sanders props for popularizing the term “socialism.” It used to be a conversation stopper. Now it is a conversation starter.

Give Bernie Sanders props for popularizing the term “socialism.” It used to be a conversation stopper. Now it is a conversation starter.

Earlier this week, Hong Kong had been rocked by perhaps the largest demonstration ever in the city’s history. In response to a murder case committed by a Hong Kong man in Taiwan, Hong Kong’s Legislative Council (LegCo) proposed a bill that would establish the transfer of fugitives between the city, Taiwan, Mainland China, and Macau. As protesters argue, this would legally allow the Hong Kong government to transfer political prisoners to China, a huge step forward for China and Hong Kong government to continue curbing political dissent. Two million people reportedly participated in the protests, more than a quarter of the city’s population. Chief Executive Carrie Lam had since agreed to indefinitely delay the bill, signaling at least a major, if not temporary, victory of the pan-democratic camp. Protests continue this week as the citizens surround the police headquarters to hold the police accountable for abuse of authority and violence in the last week and to pressure Lam to decidedly drop the bill.

Earlier this week, Hong Kong had been rocked by perhaps the largest demonstration ever in the city’s history. In response to a murder case committed by a Hong Kong man in Taiwan, Hong Kong’s Legislative Council (LegCo) proposed a bill that would establish the transfer of fugitives between the city, Taiwan, Mainland China, and Macau. As protesters argue, this would legally allow the Hong Kong government to transfer political prisoners to China, a huge step forward for China and Hong Kong government to continue curbing political dissent. Two million people reportedly participated in the protests, more than a quarter of the city’s population. Chief Executive Carrie Lam had since agreed to indefinitely delay the bill, signaling at least a major, if not temporary, victory of the pan-democratic camp. Protests continue this week as the citizens surround the police headquarters to hold the police accountable for abuse of authority and violence in the last week and to pressure Lam to decidedly drop the bill.

In 2019, the World Bank (WB) and the IMF will be 75 years old. These two international financial institutions (IFI), founded in 1944, are dominated by the USA and a few allied major powers who work to generalize policies that run counter the interests of the world’s populations.

In 2019, the World Bank (WB) and the IMF will be 75 years old. These two international financial institutions (IFI), founded in 1944, are dominated by the USA and a few allied major powers who work to generalize policies that run counter the interests of the world’s populations.

Ada Colau of Barcelona en Comú (BComú) remains mayor of Barcelona thanks to the promise of a pact with the PSC (Partit dels Socialistes de Catalunya) whose content is not yet known but which will involve a distribution of power in the town hall, and three votes of the Barcelona pel Canvi-Ciutadans group, led by Manuel Valls. This article analyses how this situation came about, how other possible solutions have been ruled out and what the possible consequences are. [

Ada Colau of Barcelona en Comú (BComú) remains mayor of Barcelona thanks to the promise of a pact with the PSC (Partit dels Socialistes de Catalunya) whose content is not yet known but which will involve a distribution of power in the town hall, and three votes of the Barcelona pel Canvi-Ciutadans group, led by Manuel Valls. This article analyses how this situation came about, how other possible solutions have been ruled out and what the possible consequences are. [

The election of a new government should be a time of celebration. 25 years since the end of Apartheid should be the time of immense celebration. Yet, 25 years since the “dawn of democracy” and South Africans are engulfed by extreme forms of anger, disillusionment and alienation. 22 million adults of voting age are so alienated that they did not even bother to participate in the national elections that brought the new Ramaphosa government into being.

The election of a new government should be a time of celebration. 25 years since the end of Apartheid should be the time of immense celebration. Yet, 25 years since the “dawn of democracy” and South Africans are engulfed by extreme forms of anger, disillusionment and alienation. 22 million adults of voting age are so alienated that they did not even bother to participate in the national elections that brought the new Ramaphosa government into being.

When in early February Algeria’s ailing octogenarian president Abdelaziz Bouteflika announced his intention to run for the presidency for a fifth term, millions of Algerians took to the streets in response. After weeks of rallies, Bouteflika was forced to resign on April 2, only to be replaced by a triad of government cronies: Abdelkader Bensalah as interim-president, Noureddine Bedoui as prime minister and Major General Ahmed Gaid Salah, who has emerged as the key power broker in the country.

When in early February Algeria’s ailing octogenarian president Abdelaziz Bouteflika announced his intention to run for the presidency for a fifth term, millions of Algerians took to the streets in response. After weeks of rallies, Bouteflika was forced to resign on April 2, only to be replaced by a triad of government cronies: Abdelkader Bensalah as interim-president, Noureddine Bedoui as prime minister and Major General Ahmed Gaid Salah, who has emerged as the key power broker in the country.

In a week of intense political polarization, the movements of the working class, youth and the oppressed again held a strong national demonstration, in continuity with the expressive acts of 15 May and 30 May. There were stoppages in more than 100 cities. Street demonstrations took place in almost 200 cities, according to the G1 website. A survey by the CUT (Central Unica de los Trabajadores) shows a map with more than 380 protest points throughout the country.

In a week of intense political polarization, the movements of the working class, youth and the oppressed again held a strong national demonstration, in continuity with the expressive acts of 15 May and 30 May. There were stoppages in more than 100 cities. Street demonstrations took place in almost 200 cities, according to the G1 website. A survey by the CUT (Central Unica de los Trabajadores) shows a map with more than 380 protest points throughout the country.

Doug Ireland, radical journalist, blogger, passionate human rights and queer activist, and relentless scourge of the LGBT establishment, died in his East Village home on October 26, 2013. Doug had lived with chronic pain for many years, suffering from diabetes, kidney disease, sciatica, and the debilitating effects of childhood polio. In recent years he was so ill that he was virtually confined to his apartment. Towards the end, even writing, his calling, had become extremely difficult.

Doug Ireland, radical journalist, blogger, passionate human rights and queer activist, and relentless scourge of the LGBT establishment, died in his East Village home on October 26, 2013. Doug had lived with chronic pain for many years, suffering from diabetes, kidney disease, sciatica, and the debilitating effects of childhood polio. In recent years he was so ill that he was virtually confined to his apartment. Towards the end, even writing, his calling, had become extremely difficult.