In April, Sudan’s president, Omar al-Bashir, was ousted in a military coup. With the head of the regime cut off, a power struggle ensued between the military junta and the popular movement demanding civilian rule. In August, the main opposition coalition and the transitional military council formally signed a power-sharing agreement following nine months of nationwide protests and brutal repression by paramilitary forces. The massive struggle from below offers a powerful example of how to fight against authoritarianism and for democracy.

In April, Sudan’s president, Omar al-Bashir, was ousted in a military coup. With the head of the regime cut off, a power struggle ensued between the military junta and the popular movement demanding civilian rule. In August, the main opposition coalition and the transitional military council formally signed a power-sharing agreement following nine months of nationwide protests and brutal repression by paramilitary forces. The massive struggle from below offers a powerful example of how to fight against authoritarianism and for democracy.

Sudan’s uprising was one of the most well organized and advanced revolts in the region. At its peak, millions were participating in sit-ins, the country was paralyzed by a general strike, and military discipline was breaking down among the rank and file. Women and union leaders were at the forefront of demonstrations. In a widely circulated video that captures the spirit of the revolution, an unnamed woman leads a march, chanting: “From Kordofan [the revolution] has emerged, after we have been hit by gunfire. This is a government with no feelings … and the Nuba mountains, like Darfur their blood is very expensive. We will protect our land, oh farmer. Our Sudan will be set free!”

This blogpost will focus on the roots of the uprising then examine the events of the 2018-2019 revolution itself with a particular focus on revolutionary agency.

The roots of Sudan’s uprising

The neoliberal restructuring of the Sudanese economy began during the 16-year dictatorship of Nimeiry (1969-1985). At the behest of the International Monetary Fund (IMF), he liberalized the economy, curbed food subsidies, and increased privatization which benefited his political Islamist party.

Rejecting the IMF measures and the implementation of sharia law, a popular uprising toppled Nimeiry in 1985 and ushered in a short-lived democratic government. In 1989, the Islamists retook power through a military coup, bringing Bashir and his National Congress Party to power. They continued to implement neoliberal policies, and the process of privatization enriched a small group of military generals. Bashir devoted an estimated 70% of the national budget to the military and security sector. Overtime, the highest strata of the military developed a significant degree of economic and political power.

In 2003, Bashir relied on the Janjaweed, a notorious group of Arab militias, to push back rebels in Darfur as part of the ongoing civil war over resources and land allocation. The resulting campaign has been called a genocide. The Janjaweed were transformed into a state-sanctioned paramilitary force called the Rapid Support Forces (RSF) commanded by General Mohamed Hamdan Dagolo (commonly known as ‘Hemedti’). Hemedti uses the RSF as a personal militia to defend his massive business empire or gold mines and airlines.

Decades of authoritarian rule, repression, racism, and crony neoliberalism wrecked Sudan’s economy and exacerbated social tensions. In 2013, people rioted over bread prices, in a prelude to the recent protests. The RSF crushed the protests, killing over 100 people and arresting hundreds more. During this wave of civil unrest, neighbourhood resistance councils developed, and these small groups of friends and neighbours worked together to share information and coordinate protests.

Sudan’s economic woes, due in large part to exorbitant military spending, were exacerbated following the succession of South Sudan in 2011. Sudan lost 75% of its oil revenue. Additionally, twenty years of U.S. sanctions largely cut Sudan off from the global financial market. Bashir responded by ramping up austerity measures, with the IMF’s encouragement. The privatization of public assets and the slashing of government food and fuel subsidies contributed to social unrest. In response to soaring commodity prices and repression by the RSF, demonstrations became a consistent feature of Sudanese civil society.

The 2018-19 revolution

In mid-December 2018, people in Atbara, a small town far away from the capital Khartoum, rioted over an increase in bread prices and burned down the headquarters of the ruling National Congress Party. An army colonel defected to the side of the protesters and prevented the RSF from entering the city. In other towns and cities, simmering economic frustration and resentment towards the regime boiled over.

Though formal trade unions had been infiltrated by the regime, independent labour organizations played a pivotal role in the uprising. In particular, the Sudanese Professionals Association (SPA) took a lead in coordinating protests and came to be seen as the organic leadership of the movement. This network of banned trade unions formed through struggle in 2016, is composed of professional workers such as doctors, lawyers, engineers, and journalists. These workers led increasingly precarious lives as wages declined, working conditions worsened, and the lifting of government subsidies threatened their social position.

The demands for economic justice quickly broadened to calls for the regime to fall. On the 1 January, 2019, the Forces for Freedom and Change (FFC), a broad opposition coalition spearheaded by the SPA of workers associations, liberal and leftist political parties, feminist groups, and armed movements, published a list of demands. At the top was the end of Bashir’s presidency.

The revolt continued to gain momentum, reawakening old networks and drawing on experience from past struggles. On 6 April, the anniversary of the 1985 popular uprising, protesters began a massive sit-in at the army headquarters in Khartoum. Similar sit-ins began in other cities. They became a gathering place for millions of people to debate the way forward, share community meals, and sing revolutionary songs. The outpouring of creative resistance and solidarity offered a glimpse into another possible society.

Though the regime has systematically disenfranchised rural parts of the country and used racism to reinforce the urban/rural divide, the movement permeated rural communities as well. Unlike in 2013, urban resistance was matched by rural struggle. In many places, student led the way with mass marches, and the armed movements followed this non-violent lead. The FFC included the Sudan Revolutionary Front, an alliance between armed rebel groups largely based in peripheral areas. When the regime attempted to use racism divisively, the chant went up, “Ya onsori wa maghroor, kol albalad Darfoor!”/“Hey racist [Omar Al-Bashir], we are all Darfur!” in an extraordinary show of anti-racist solidarity.

The regime responded to the movement with violence. On 6 April, military and security forces attempted to violently disperse the sit-ins, killing dozens of protesters. Called to fire on fellow citizens, some junior army officers and lower ranking soldiers refused their orders, and several were killed defending the popular movement. The revolutionary consciousness spreading among the lower ranks of the army terrified the high command.

On 11 April, the generals disposed Bashir, gambling on a coup in order to avoid a collapse of the army and placate the people. The military announced a Transitional Military Council (TMC) headed by Defence Minister Awad bin Auf, a man with direct connections to atrocities committed in Darfur. He was forced to step down within 36 hours. General Abdel Fattah al-Burhan, Bashir’s former chief of staff and head of ground forces, took his place. Hemedti, head of the RSF, emerged as the de facto leader of the TMC.

The formation of a military junta did not quell the protests. Having learned the lesson of Egypt’s revolution, the movement refused to leave the streets until the military ceded power. In the words of Sudanese activist, Mohamed Mustafa Diab, ‘The Sudanese people understand that the enemy is not a single man; it is the whole regime and everything it represents…“A civilian government or an eternal revolution.” That is one of the most popular slogans right now. As long as we maintain pressure, we — the Sudanese people — will have the final say.’

Foreign powers quickly backed the Sudanese military, hoping to preserve the structure of the state. Saudi Arabia has benefitted from thousands of RSF troops fighting in their bloody war in Yemen. European nations rely on RSF soldiers to patrol the desert and prevent migrants from reaching Europe. Abdel Fattah el-Sisi, Egypt’s military dictator and head of the African Union, eased political pressure on the TMC in an effort to promote stabilization.

In late April, the FFC and the TMC entered into a stormy process of negotiations brokered by the African Union and Ethiopia. The negotiations were compromised from the start. In May an article by a small group of socialists in Egypt clearly articulated the contradiction:

the problem is not so much the personalities of the negotiators as the overall strategy of the opposition. By agreeing to negotiate with Al-Bashir’s generals, and allowing them to participate in the transition period, the leaders of the opposition are trying to reconcile the demands of the revolutionary street on the one hand, and the counter-revolutionary generals on the other. This strategy is suicidal for the revolution. Regardless of who the negotiators are, they will betray the hopes of the revolutionaries.

The TMC threatened its negotiating partners with arrest and, when talks broke down, conditioned resumption of discussion on compromise. They repeatedly demanded an end to the sit-ins and a dismantling of the barricades set up around Khartoum. Whenever the FFC called off negotiations, they came back to the table before winning significant demands or conditions.

Much of the negotiating process was opaque. According to Hajooj Kuka, a neighbourhood resistance committee activist, this lack of transparency was frustrating for the movement. He explained, ‘the people who are on the street, who are organizing these protests, who are out and protesting, and putting their lives in danger, don’t really know what’s happening. And this attitude that there’s a few elitists who know better and who should negotiate in hiding… is really against the revolutionary feel of what’s happening on the ground.’

This negotiation strategy can be explained in part by the political parties within the FFC that have traditionally functioned as the institutionalized opposition to Bashir. Their method of negotiating with the regime and participating in parliament primed them for a compromise with the military. Additionally, the class position of many of the FFC members and explicitly those within the SPA influenced the negotiations. As professional workers, they were more willing than the movement in the streets to trust the generals.

In organization and in rhetoric, the SPA did not pose itself as a political alternative to Bashir’s neoliberal, autocratic regime. The organization was strictly not a political party. The seemingly apolitical nature of the SPA likely appealed to many people who distrusted political parties. Though the SPA impressively united the resistance to Bashir in the FFC, it missed the opportunity to reclaim or redefine leftist politics in this moment.

The mobilization rhetoric of SPA derived from Sudan’s effendiya, a nationalist ideology of the small class of Sudanese who were educated to fill the ranks of the civil service during colonialism and who were prepared for post-colonial rule. This framework was too narrow to speak to the diversity of the Sudanese people and reimagine a Sudan that embraces all, across ethnic, racial, religious lines. The dominant slogans of “peace, freedom, and justice” and ‘mandaniyaa’ (civilian) fail to wed political demands with class demands in a moment ripe for a revolutionary message. Rather than drawing from alternative frameworks of the working class or the feminist movement, the SPA appealed to the universal rights and freedoms of citizens, using language that is not incompatible with the neoliberal state.

The failure to centre class demands and implicitly or explicitly raise revolutionary slogans may partially explain why Khartoum’s peripheral neighbourhoods of poor and displaced people did not join in the protests as enthusiastically as the middle-class neighbourhoods.

Turning point and road to constitutional agreement

As negotiations unfolded after April, the popular movement continued to express itself in the streets, demanding civilian rule. The security forces and the RSF continued their repressive campaign of intimidation, arrests, and murder. In late May, the country participated in a 2-day general strike.

3 June marked a turning point in the revolution. On this day, the last day of Ramadan, the TMC imposed a countrywide internet blackout and sent in the RSF to clear the Khartoum sit-in. The paramilitary force massacred over 100 people, raped dozens, and injured over 500 others. According to eyewitness Mohammed Elnaiem, ‘[The RSF and army] started shooting at us and we all started running away from the barricades, and running into houses to hide. I haven’t been brave enough to go outside to rebuild the barricades like some other people have been since then. It’s terrifying. There’s gunshots everywhere. In my neighborhood there is reports of a sniper in an abandoned building. I don’t know where specifically so it’s really risky. They want to terrorize us at home.’

In response, the FFC suspended negotiations. The SPA published a list of immediate demands to be met before talks resume. They called for an open-ended political general strike. From 28 May to 29 May, over 80% of the population participated in the strike, shutting down most of the country. Three days after the start of the strike, the SPA called for it to end. The FFC re-entered negotiations with the very forces that were responsible for 3 June massacre before they had been brought to justice.

But in the streets, the masses advanced ahead of the leadership of the movement. They insisted on retribution for the killing and wounding of protesters. The TMC had lost its moral authority, and mass demonstrations for civilian rule and justice for 3 June martyrs took place across Sudan. On 1 July, the SPA published a 2 week-long plan that matched the militancy of the street. Marches and demonstrations were to culminate in a general strike on 14 July.

However, four days later, the FFC and TMC reached a verbal agreement to share power. The FFC cancelled protests for the upcoming week and organized demonstrations in support of the deal.

Immediately, some of the FFC coalition members publicly condemned the tentative deal. A statement from the Darfur Displaced General Coordination (DDGC) read, ‘The aim of this agreement is also to block the realisation of the goals of the revolution: to bring down the regime, prosecute its criminals, achieve freedom, peace and justice, establish a civilian-led government, resolve the civil wars in the country and restore the rights of displaced people and refugees.’ The Sudan Revolutionary Front, a coalition of armed movements, rejected the deal as did the Sudanese Communist Party who withdrew from negotiations and called for popular protests to continue.

The struggle advances

On 4 August, the FFC and TMC signed a constitutional declaration that marked the beginning of a 39-month long transitional period. Until elections in 2022, Sudan will be governed by a sovereign council composed of 5 civilian members, 5 military members, and 1 member chosen jointly. A military member will lead for the first 21 months, and then a civilian member will lead for the last 18 months.

The declaration establishes a council of ministers tasked with implementing its mandates during the transitional period. The FFC nominated economist Abdalla Hamdok as prime minister, and he will select ministers from a list prepared by the FFC. The defence and interior ministers will be appointed by military members of sovereign council.

The declaration also establishes an appointed transitional legislative council that will be majority civilian with 67 members from the FFC and 33 members from other political forces that were not part of the FFC. In a significant victory, no fewer than 40% of the council members must be women.

All potential ministers and legislative council members must be confirmed by the sovereign council, and decisions on the sovereign council must be adopted by a two-thirds majority. This means that the minority of military members can veto decisions, in essence nullifying the rule of civilians on the country’s highest authority.

A few days after the signing of the accord, the SPA announced that it would not take any of the civilian seats on the sovereign council. They intend to participate in the legislative council ‘as an independent regulatory authority’ and ‘watchdog’ to ensure the mandates of the declaration are carried out during the transitional period.

The declaration did not include concrete economic reforms, specific mandates to improve the rights of women and youth, a plan to prosecute those responsible for war crimes, nor a rigorous investigation of 3 June massacre. The failure to include social and economic reforms leaves many of the movement’s central demands unrealized. The deal also dodged larger questions of war and peace, racism and marginalization, and the rights of displaced persons and refugees.

Despite its limitations, jubilant crowds gathered in Khartoum to celebrate the signing of the deal. Sara Abdelgalil of the SPA told the New York Times, ‘It’s a very tough compromise. We just hope that we will achieve a civilian-led government at the end of the three years. And if we fail, we will go back to the street.’

Ordinary activists expressed similar resolve. Ramzi al-Taqi, a fruit seller in Khartoum, told Agence France-Presse, ‘If this council does not meet our aspirations and cannot serve our interests, we will never hesitate to have another revolution. We would topple the council just like we did the former regime.’

Conclusion

Sudan is in a state of acute contradiction as popular forces share power with the very actors that repressed the movement. As Sudan enters the next phase of its revolution, much hinges upon whether the FFC can win over a majority of the rank and file soldiers in support of the people.

Bashir’s trial has begun over corruption charges, but many question whether he will be held accountable for his greatest crimes. Some suspect that the military is using the trial to deflect attention away from 3 June massacre.

Newly appointed Prime Minister Hamdok has approved 14 civilian minsters from a list provided by the FFC. He reiterated that this is meant to be a government of ‘technocrats’ rather than politicians. Among his selections are Asmaa Abdallah as Sudan’s first female foreign minister and Ibrahim Elbadawi, a former World Bank economist, as finance minister. Hamdok has also reached out to the World Bank and IMF to discuss Sudan’s debt.

Many of the problems that led millions of Sudanese to revolt – decades of repression, lack of democracy, neoliberal austerity, the unrealized rights of refugees – have not been resolved. Bread and fuel queues have already begun to reappear. The revolutionary process is not over and, as it unfolds, the Sudanese people who have now felt their power, will undoubtedly fight to shape their own destiny.

In the midst of the 6 April sit-in in Khartoum, a mass movement in Algeria overthrew long time, autocratic president Abdelaziz Bouteflika, imbuing Sudanese protesters with confidence. The emergence of these concurrent movements indicates that the conditions that gave rise to the Arab Spring and protests in Burkina Faso and Senegal will continue to spark resistance.

Assessing and learning from these movements remains an urgent task. They raise important questions about the level of trade union and working-class involvement, the weakness of organizations and political parties, the ‘absence of ideology’ of the main opposition groups, and the role of the organized left and its revolutionary wing.

This article originally appeared on The Review of African Political Economy. Featured Photograph: A work by Khalid Kodi showing a Sudanese woman in front of the military HQ in Khartoum; the RSF militia raped dozens of women and killed more than 100 protesters on 3 June as they broke-up the sit-in at the military HQ (16 July, 2019).

At the national, state, and even local level, union political endorsements are often made with insufficient membership involvement.

At the national, state, and even local level, union political endorsements are often made with insufficient membership involvement.

Sunday, September 22, 2019, from 7 p.m. to 10 p.m. Geneva time

Sunday, September 22, 2019, from 7 p.m. to 10 p.m. Geneva time

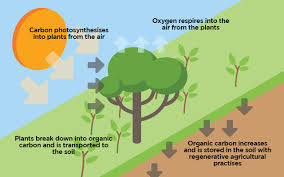

chemistry; chemical fertilizers take care of that (to a point). And if monoculture attracts pests, then modern pesticides can take care of that too. The resulting soil depletion (also due to plowing the soil) are compensated for by ever increasing doses of chemicals. These facts lead to a policy that rewards the huge growers.

chemistry; chemical fertilizers take care of that (to a point). And if monoculture attracts pests, then modern pesticides can take care of that too. The resulting soil depletion (also due to plowing the soil) are compensated for by ever increasing doses of chemicals. These facts lead to a policy that rewards the huge growers.

One of the biggest complaints leftists make about progressive activism—at least in more candid moments—is a failure to communicate effectively. Since Newt Gingrich and Fox News fundamentally changed the dynamics of political agitation in the 1990s through amping up the spectacle and doubling down on hyper-partisanship, many have complained that progressives simply couldn’t compete in terms of political optics. This discrepancy was nicely spoofed by Contrapoints in her early video “The

One of the biggest complaints leftists make about progressive activism—at least in more candid moments—is a failure to communicate effectively. Since Newt Gingrich and Fox News fundamentally changed the dynamics of political agitation in the 1990s through amping up the spectacle and doubling down on hyper-partisanship, many have complained that progressives simply couldn’t compete in terms of political optics. This discrepancy was nicely spoofed by Contrapoints in her early video “The

Jamie Margolin speaking to a crowd of youth climate activists. (Facebook/Zero Hour)

Jamie Margolin speaking to a crowd of youth climate activists. (Facebook/Zero Hour) Greta Thunberg (center) joined other climate striking youth in New York City last month. (Twitter/@GretaThunberg)

Greta Thunberg (center) joined other climate striking youth in New York City last month. (Twitter/@GretaThunberg)

In April, Sudan’s president, Omar al-Bashir, was ousted in a military coup. With the head of the regime cut off, a power struggle ensued between the military junta and the popular movement demanding civilian rule. In August, the main opposition coalition and the transitional military council formally signed a power-sharing agreement following nine months of nationwide protests and brutal repression by paramilitary forces. The massive struggle from below offers a powerful example of how to fight against authoritarianism and for democracy.

In April, Sudan’s president, Omar al-Bashir, was ousted in a military coup. With the head of the regime cut off, a power struggle ensued between the military junta and the popular movement demanding civilian rule. In August, the main opposition coalition and the transitional military council formally signed a power-sharing agreement following nine months of nationwide protests and brutal repression by paramilitary forces. The massive struggle from below offers a powerful example of how to fight against authoritarianism and for democracy.

On Friday, July 12, after almost two years of discussion, the Swedish minister of foreign affairs, Margot Wallström of the Social Democratic Party, announced that the government has decided to not sign the UN Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons. Wallström gave two reasons why she decided to not sign it: 1) the treaty in its current form is unclear on some definitions such as what kind of weapons are concerned and how the disarmament shall happen, and 2) if she would take the treaty to the parliament, the most likely outcome is that a majority would vote against signing it.

On Friday, July 12, after almost two years of discussion, the Swedish minister of foreign affairs, Margot Wallström of the Social Democratic Party, announced that the government has decided to not sign the UN Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons. Wallström gave two reasons why she decided to not sign it: 1) the treaty in its current form is unclear on some definitions such as what kind of weapons are concerned and how the disarmament shall happen, and 2) if she would take the treaty to the parliament, the most likely outcome is that a majority would vote against signing it.

Editors’ note: This is the second of three articles providing analysis of what’s happening now in China – and why.

Editors’ note: This is the second of three articles providing analysis of what’s happening now in China – and why.

Mitchell Abidor, ed. and trans. The Permanent Guillotine: Writings of the Sans-Culottes. Oakland: PM Press, 2018.

Mitchell Abidor, ed. and trans. The Permanent Guillotine: Writings of the Sans-Culottes. Oakland: PM Press, 2018.

The irony of India celebrating its 72nd year of national independence as it orchestrates a coup and military lock-down on the occupied territory of Kashmir was apparently lost on Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi.

The irony of India celebrating its 72nd year of national independence as it orchestrates a coup and military lock-down on the occupied territory of Kashmir was apparently lost on Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi.

Ceaseless shootings, extrajudicial executions, houses invaded both by the military police and by militias, schools closed, firearms being discharged from the sky, and a country burning: it could be a war scenario, but this has been the day-to-day experience of the poorest Black and Indigenous sections of the Brazilian working class under the Bolsonaro government. The blame – the president states – lies with the NGOs and human rights defenders.

Ceaseless shootings, extrajudicial executions, houses invaded both by the military police and by militias, schools closed, firearms being discharged from the sky, and a country burning: it could be a war scenario, but this has been the day-to-day experience of the poorest Black and Indigenous sections of the Brazilian working class under the Bolsonaro government. The blame – the president states – lies with the NGOs and human rights defenders.

The Bernie Sanders presidential campaign presents socialists with an unprecedented opening for explicitly socialist politics. And Sanders’ Workplace Democracy Plan (WDP) represents a coherent set of policies through which to examine that opportunity. In

The Bernie Sanders presidential campaign presents socialists with an unprecedented opening for explicitly socialist politics. And Sanders’ Workplace Democracy Plan (WDP) represents a coherent set of policies through which to examine that opportunity. In

Fifty years ago this fall, a campus upsurge turned opposition to the Vietnam War into a genuine mass movement.

Fifty years ago this fall, a campus upsurge turned opposition to the Vietnam War into a genuine mass movement.

The discredit attained by the dominant parties, by the legislature, by the “politicians” and even “politics” itself, defined inaccurately, but viscerally despised by many people, recalls the concept of “organic crisis” advanced by the Italian Marxist Antonio Gramsci. Authors such as Stathis Kouvelakis have used it to analyse the movement of the gilets jaunes in France. An organic crisis involves a breakdown of the ability of the ruling class to “maintain its leading role”. One of its “most visible symptoms” is the “collapse of support for traditional parties”.

The discredit attained by the dominant parties, by the legislature, by the “politicians” and even “politics” itself, defined inaccurately, but viscerally despised by many people, recalls the concept of “organic crisis” advanced by the Italian Marxist Antonio Gramsci. Authors such as Stathis Kouvelakis have used it to analyse the movement of the gilets jaunes in France. An organic crisis involves a breakdown of the ability of the ruling class to “maintain its leading role”. One of its “most visible symptoms” is the “collapse of support for traditional parties”.

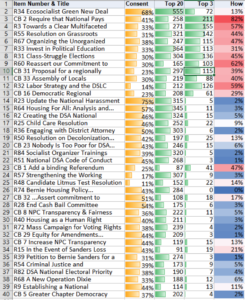

Earlier this month, the Democratic Socialists of America (DSA) held its 2019 National Convention. I

Earlier this month, the Democratic Socialists of America (DSA) held its 2019 National Convention. I