In early December of 2017 the Trump Administration officially withdrew the United States from the UN Global Pact on Migration, claiming the 2016 accord “undermine[s] the sovereign right of the United States to enforce our immigration laws and secure our borders.” The aligned governments of Israel, Hungary, Poland, Australia, Austria, and several other countries followed suit in withdrawing their support, or by publicly repudiating the agreement. Right-wing parties in Germany, France, Italy and Denmark also vocalized their opposition, pledging to withdraw once in power.

In early December of 2017 the Trump Administration officially withdrew the United States from the UN Global Pact on Migration, claiming the 2016 accord “undermine[s] the sovereign right of the United States to enforce our immigration laws and secure our borders.” The aligned governments of Israel, Hungary, Poland, Australia, Austria, and several other countries followed suit in withdrawing their support, or by publicly repudiating the agreement. Right-wing parties in Germany, France, Italy and Denmark also vocalized their opposition, pledging to withdraw once in power.

Given such choreographed denunciation, one might think that this pact contained unprecedented directives designed to override current immigration practices and policies. Quite the opposite.

Its 23 provisions primarily affirm national rights to police migration, control and close borders, and criminalize, detain, and deport migrants and refugees as they see fit. For instance, while claiming they are are entitled to rights, it states that “migrants and refugees are distinct groups governed by separate legal frameworks” according to each nation’s particular needs by “…taking into account different national realities, policies, priorities and requirements for entry, residence and work.”

The pact does contain platitudes about the need for international cooperation, standards, and orderly processes to regulate the flow of a growing stream of transnational and stateless people. It suggests that nations maintain some semblance of legal access to citizenship, to create transnational arrangements to prevent significant loss of life (such as what occurs along the US-México border or in the sea lanes between North Africa and Southern Europe), to provide basic services to migrants within national territories, and take steps to curtail racist and xenophobic hate crimes. To underline the purely suggestive nature of this pact, it is not binding for its signatories.

That this pact was previously signed by Barack Obama—whose administration championed it internationally—should give some pause and diminish its credibility as being inherently “pro-migrant and refugee.” The largest buildup and activation of the infrastructure of migrant repression in the world and in history, occurred during the eight years of the Obama Administration.

Destabilization and political crisis

Transnational migration has increased alongside widening social inequality within nations. These are both the result of over three decades of neoliberal capitalism. Internationally, neoliberal policies have economically destabilized and displaced whole populations in poor nations. This has occurred primarily through the coercive opening and colonization of smaller economies (through so-called “free trade” agreements), and the exposure of smaller producers within the subject nation to direct competition with exponentially larger multinational corporations and finance capital operating through investment banks and other instruments.[1]

With less resources to absorb internally displaced people in poor countries, out-migration has increased on a global scale. Within rich nations, these policies have also produced economic destabilization for the working classes, through the export of jobs, wage suppression, tax cuts, privatization, union-busting, and the slashing of social budgets. Since there are generally more resources available within the rich nations, there tends to be less out-migration, although it has been increasingamong some specific groups in the case of the US.

The economic instability generally afflicting the working classes in the rich nations has led to significant abandonment of traditional centrist, liberal, and social democratic parties, especially where those parties have directly administered their slide into precarity.

These factors have contributed to the decline and collapse of these parties. The decomposition of traditional centrism, liberalism, and social democracy on an international scale has allowed far-right groups in a growing list of countries to co-opt popular resentment against capitalism and re-direct it towards other victims. At the top of this list of targets are migrants, refugees, and other stateless people, who are also the victims of the global capitalist system.[2] This has proceeded with the criminalization of migration, fortification of borders, and exclusion from citizenship rights. This has now contributed to the demise of the pact.

The quick crack-up of even a modest agreement on international migration may reveal the inherent weaknesses of overlaying international law across an inherently divided, unequal, and increasingly unstable capitalist system. This is especially the case as we watch the unfolding of a new epoch of imperialist re-division of the world between the declining US and rising China, which is fracturing existing global arrangements from climate crisis to nuclear proliferation to trade. The death of the pact is another symptom of a deepening political crisis of legitimacy for the capitalist system, and how the political far-right is taking advantage of the moment.

The growing clamor to close borders and detain and deport migrant people is principally rooted in their class position as workers. As migrants, refugees, and other stateless people comprise significant and growing segments of the working classes in the receiving nations, the more they become a factor in the equation of the relations of production. The more their labor can be controlled, disenfranchised, made legally vulnerable—and therefore atomized—the more it can be exploited, leveraged against other workers, and the more profit extracted from all.

In the US, where the economy has been geared by migrant labor over several historical cycles, the apparatus of migrant repression has become most boundless, ubiquitous, and brutal. The most recent phase originates in the 1970s, as the ideologues and political stewards of the capitalist class began to look for means to increase the rate of labor exploitation amidst decline. This included numerous approaches, starting with the coordinated attack on unions. They also turned to immigration policy and citizenship restriction.

Since the 1980s, US capitalism has become increasingly dependent on the exploitation of migrant labor, which has increased in proportion to the imposition of international economic policies and debt-restructuring that have fueled displacement.

Over that period—and rapidly accelerating since the turn of the 21st century—both US capitalist parties have constructed a vast ideological and legal edifice for the criminalization and super-exploitation of migrant people. The scale of repression has reached new heights under Donald Trump. It is being replicated in other parts of the world as a reaction to its successful implementation in the US as a means of accumulation, because of the implications this carries for economic competition between centers of capital, and as a means to scapegoat migrants for political purposes.

Repression of migration is not a new phenomenon, but its character has qualitatively changed. It is and will likely continue being generalized as a response to the failures of capitalism in different parts of the world.

Migrant repression becomes a model

Wage suppression through the criminalization of migrant people has become a feature of capitalist accumulation in the rich capitalist countries as well as in rising capitalist economies, albeit in different forms. Furthermore, the expansion of the state repressive infrastructure under the semblance of stopping unlawful migration has become a secondary source of profit-making. While ostensibly targeting one population, it is leading to the militarization of society under the aegis of “securitization”.

This process can be observed in different ways. These include the proliferation of border wall construction and expansion, the growth and multiplication of special bodies of armed agents with unprecedented policing powers and operational impunity. It is seen in the rapid build-up of detention capacity, full-spectrum surveillance, and the use of military and technological instruments against civilian populations.

The calculated targeting of migrants, refugees, and other stateless people in the rich countries has legitimized the practice for other governments, who are utilizing the political construct of “citizenship” to repress and marginalize populations within their own states for their own purposes.

The architecture and ground forces of repression currently being tested and tuned against migrants and refugees is also being honed for use against wider sectors of the population, especially as indicators show rich and rising capitalist nations becoming more polarized and unstable. Social unrest, popular uprisings, and revolts across all continents have been intensifying since the alleged recovery from the Great Recession of 2008-2010.[3]

Even the United States, by far the richest nation, is becoming more politically polarized as the working class becomes more precarious. A 2017 US National Intelligence Council report concluded that over the next 5 years the US government would

[find] it harder to manage rising public demands for greater economic and social stability at a time when budget constraints and debts are limiting options. Public frustration is high throughout much of the region, because uncertainty about economic conditions and social changes is rising at the same time that trust in most governments is declining.

This provides the backdrop for the persecution of migrants within different national contexts. In response, many states are paring back democratic norms. A 2018 report that charts democratic practices on a global scale recorded the 13th consecutive year of decline in “global freedom,” including consistent declines in the US and in Europe overall.

The escalation of authoritarianism in nominally democratic societies and subsequent social militarization can be understood as a materialization of capitalist class consciousness. This is expressed in the form of a state-directed response to the social crisis that is rendering the working classes more volatile and oppositional. More specifically, it is the ramping up of state-repressive capacity in response to the growth of discontent of working class people internationally, and how episodes of unrest, resistance, and revolt are likely to intensify.

Most poor and working class people have not recovered from the last crisis. This reality is shared with that of economically displaced people internationally, who enter into the national workforce alongside other workers. Through criminalization and the denial of citizenship rights (freedom of movement, democratic participation, the right to petition for redress of grievances, union rights, etc.) capitalists have systematized the practice that they can exploit all workers more effectively by leveraging one against the other. Through the history of capitalism the maximization of exploitation has depended on the legal and social subdivision of workers based on an evolving set of factors administered through the state. The marginalization of migrants has become the most recent manifestation of this cyclical process.

Migrants have become a significant share of the labor force in many advanced capitalist economies. Simultaneously, we see the perpetuation of national and international neoliberal governance regimes that continue to systematically redistribute wealth from the majority of poor and working class people to the minority of rich. This produces the combustible mix of factors that characterize the different paths coming into focus in the current period: episodes of resistance and revolt on the one side, and the ratcheting up of state repression on the other.

Intensification of inequality, poverty, and displacement migration

Global capital has become so concentrated nationally and free to move across borders, that is creating unprecedented levels of inequality. In the United States, the top 1%

owns nearly $30 trillion of assets while the bottom half owns less than nothing, meaning they have more debts than they have assets… “Between 1989 and 2018, the top one percent increased its total net worth by $21 trillion…The bottom 50 percent actually saw its net worth decrease by $900 billion over the same period.”

This pattern is also playing out internationally, illustrated by a report showing that the wealth of the 26 richest people surpasses what is collectively held by 3.8 billion people, or half of the global population. Furthermore, the arc of inequality is increasing more rapidly each year, with one new billionaire created every two days between 2017 and 2018 alone.

Inequality and displacement are further exacerbated by war, climate change, lack of access to housing, medical care, clean drinking water, and other social factors that are not necessarily captured in abstract wealth statistics. There has been no “recovery,” only on-going economic crisis for working class, poor, and displaced people the world over.

Displacement as a result of economic policy, war, climate crisis (and other factors) is generating a growing transnational migrant and refugee population, estimated to be 272 million people in 2019, an increase of 51 million since 2010. In the US and Europe, two of the main global centers of capitalism, the migrant population has been growing each year since 1990. In Europe, North America, Australia, New Zealand, and Japan, 12 out of every 100 inhabitants are migrants, compared to only 2 per 100 in the Global South. Over half of all global migrants reside in the US and Europe alone. The number of global refugees, as a percentage of this population in the US and Europe has nearly doubled between 2009 and 2018.

Structures of inequality within nations also affect how finite resources are distributed within economies, with land, natural resources, state supports, and other important inputs disproportionately concentrated in the hands of large capitalist producers. This has occurred most starkly through the aegis of free trade agreements. These commonly remove tariffs and restrictions that allow highly capitalized multinational corporations and international investors with international production and distribution networks to permeate and operate within and across national markets to compete directly with local producers. This has contributed to the collapse of small businesses, family and subsistence farming, and other smaller-scale production and distribution operations in many countries.

Traditional social and economic measures do not account for the fact that there has been no recovery for significant sectors of populations within capitalist economies. As a measure of financial well-being, banks in the US and internationally have not only been restored to pre-recession profitability rates, but have dramatically increased their profits since the crisis. The global working classes, poor, and economically marginalized populations endure varying degrees of permanent economic crisis, afflicting populations within and across nation states.

Instead of examining the underlying and systemic causes of this crisis, poverty is instead criminalized. The narrative of the undeserving and unproductive poor allows the capitalist state to build social consensus for the downsizing of welfare. Migrant and refugee populations are then enmeshed as a secondary category of the “criminal” poor, further justifying cuts in public and social services for all people, regardless of citizenship.

Repression is profitable

Displacement migration not only results from the forces driving global inequality, but inequality also derives from the exploitation of disenfranchised migrant labor. As a report by the Economic Policy Institute explains:

Unauthorized immigrants, who make up nearly 5% of the U.S. labor force, contribute to the economy in vital industries and pay billions in taxes and contributions to the social safety net. But these eight million workers are not fully protected by U.S. labor laws because of their precarious immigration status: Unauthorized workers are often afraid to complain about unpaid wages and substandard working conditions because employers can retaliate against them by taking actions that can lead to their deportation. That also makes it difficult for unauthorized immigrants to join unions and help organize workers. This imbalanced relationship gives employers extraordinary power to exploit and underpay these workers, ultimately making it more difficult for similarly situated U.S. workers to improve their wages and working conditions.

Undocumented and other non-citizen workers experience widespread forms of wage suppression, including being denied the right to engage in collective bargaining and seek legal recourse, being paid less than minimum wage, not receiving overtime pay, being denied social benefits despite paying taxes, and myriad other ways and forms.

While this snapshot shows how repression of migration benefits capital currently, the incremental intensification of super-exploitation of transnational workers has risen in conjunction with the criminalization of migration over the last three decades. Labor repression for a segmented labor force has grown into a sprawling complex of laws, norms, customs, cultures, and practices that fragment the working class into various sections and subsections.

Whether migrants or refugees, the vast majority of these people enter the workforce as non-citizens. Their labor exploitation has become an important component of how capitalism now functions within these countries. Secondly—and growing out of the first—is the role that migrant-repression plays in the electoral sphere. Repression has become a lucrative industrial commodity allowing whole new industries to rise and flourish. It is also opening up portals for the re-emergence, reorganization, and reintegration of the fascist far-right into the mainstream of bourgeois political discourse.

The economic exploitation of migrants and refugees and the xenophobic exploitation of migration as a political issue at the level of the nation state are occurring in tandem internationally, although in different ways, forms, and speeds.

The global recession that produced the first significant post-war crisis of accumulation in the early 1970s set into motion the neoliberal turn. This refers to a period of reorganization of the state in which it became a more overt and unmasked instrument of class rule. More specifically, it signaled a period of direct repression and atomization of working class organization and the dismantling and smashing up of three decades of accumulated social reform and welfare provisions.

This is only possible through the aegis of the bourgeois governance structure as “the neoliberal state assumes the central role of both supporting and promulgating these practices, by way of its possessing a monopoly over violence and definitions of legality.”

Neoliberalism has also manifested internationally through growing capitalist expansion and corporate-led integration across national boundaries. This has been legally adjudicated through so-called free-trade agreements, IMF-facilitated debt-restructuring requirements, aid projects, and other means.

This radical redistribution of wealth from the working class to the bourgeoisie in order to restore and increase profitability reveals a novel solution to the crisis of the method of traditional capitalist accumulation, which has been typically achieved through “natural” expansion of markets and organic growth of exploitable labor. Yet the containment of migrants as a subjugated labor force remains predicated on at traditional capitalist social relation: the intensification of the exploitation of labor.

One important tactic for increasing the exploitation rate of migrants occurs through what Karl Marx described as the construction of a reserve army of labor. As he explained in Capital,

We have seen that the development of the capitalist mode of production and of the productive power of labor — at once the cause and effect of accumulation — enables the capitalist, with the same outlay of variable capital, to set in action more labor by greater exploitation (extensive or intensive) of each individual labor power. We have further seen that the capitalist buys with the same capital a greater mass of labor power, as he progressively replaces skilled laborers by less skilled, mature labor power by immature, male by female, that of adults by that of young persons or children.

On the one hand, therefore, with the progress of accumulation, a larger variable capital sets more labor in action without enlisting more laborers; on the other, a variable capital of the same magnitude sets in action more labor with the same mass of labor power; and, finally, a greater number of inferior labor powers by displacement of higher.

The politicization and manipulation of access to citizenship therefore becomes a lever used by the state to subjugate the legal and social status of migrants. The denial of citizenship has been coupled with an incessantly expanding apparatus of repression in the form of laws, swelling ranks of special bodies of armed agents, and the cultivation of xenophobia, racism, and anti-immigrant sentiment among segments of the population that can be mobilized as a political bulwark.

Agents of repression are situated across all nodes of social and economic interface to then police the presence of migrant people—without actually removing the whole of them. This diminishes their mobility, prevents participation in civic and political affairs, and forms spatial, social, and political divides between them and other concentrated populations of the working class. Over time, the totality of this this function of capitalism has led to the establishment a form of neo-segregation nationwide with similar features and functions as Jim Crow.

This landscape in turn creates the conditions that enable capitalists within a widening range of industries to intensify the rate of exploitation of non-citizen labor. Successful suppression of one segment of the working class then enables the leveraging downward of the threshold for all labor.

The political economy of migrant repression

Criminalization of migration and the demonization of migrants begins within the political sphere of the nation-state. While substantive changes in the political orientation of a state towards controlling migration may be the result of seismic events, such as an act of terrorism, they enable radical shifts and the release of accumulated and pent-up tensions already building up within the capitalist system itself. Reactionary impulses towards the repression of migrants are the portal through which a wider reorganization and of the political economy can proceed. Repression becomes a political and economic product. Securitization under neoliberalism allows for new markets to grow, such as surveillance and incarceration, while holding down wages for the whole working class.

This may explain why these labor suppression is increasing on an international scale along similar patterns. There are at least 77 border walls or fences around the world, with many being erected after the Sept. 11, 2001 attacks in the US. The Bush administration and a supportive bipartisan congress initiated a rapid wall expansion project, ushering in the current epoch of border militarization, immigrant persecution, and the reemergence of overt reactionary nationalism and racism in new configurations.

It also explains the branching off of the profitability of repression and incarceration as distinct growth industries. A recent study by the Transnational Institute documents the unchecked and towering growth of the immigrant repressive apparatus in the US.

[B]udgets have more than doubled in the last 13 years and increased by more than 6000% since 1980…This has created a seemingly limitless market for border-security corporations…[it is projected] that this will be a $52.95 billion market by 2022.

According to an estimate based on this data, the border security industry will more than double in value from approximately $305 billion in 2011 to $740 billion in 2023. This unchecked behemoth infrastructure with over 60,000 armed agents and support personnel now extends from the border into every corner of the country. These are also assisted by thousands of police officers from 89 police jurisdictions across 21 states that currently have 287(g) agreements allowing for their participation in ICE operations.

These forces hunt, retrieve, detain and deposit people into a sprawling complex of at least 637 known detention camps spread across the country, and an unknown number of black sites.

A report by the Economic Policy Institute concludes, “A comparative analysis of 2018 federal budget data reveals that detaining, deporting, and prosecuting migrants, and keeping them from entering the country, is the top law enforcement priority of the United States.”

Sharply implemented changes have produced an observable qualitative shift in national priority towards securitization resulting in authoritarian impulses, technological shifts towards social control, and enhanced capacities for repression—all under the rubric of “national security.” According to one comprehensive study,

Since 9/11, the United States has gradually moved away from nationality-based policies toward a redesigned immigration enforcement machinery that is conceived, driven, and funded with the central goal of advancing national security. It has resulted in the creation of a new Cabinet agency, the Department of Homeland Security; the creation or expansion of vast databases for the collection and analysis of information; new life for long-authorized but languishing initiatives; and the growth of a new generation of cooperative relationships between federal, state, and local law enforcement agencies.

In a relatively short period of time, we have seen exponential growth in armed state enforcement bodies, surveillance and monitoring systems, incarceration capacity, and laws criminalizing political activity. Anti-migration has allowed the state to build up an unprecedented apparatus that is being primed for the potential use against the whole population. While the current composition of the US state cannot be defined as fascist—in classical Marxist terms—there are transitory processes occurring that reveal a quantitative shift in that direction. These include: the specific violent targeting of racialized migrants within the context of profound social inequality, the growth and legal transcendence and impunity of special bodies of armed repressive agents, expanding capacity of fascist groups to carry out acts of mass violence and private repression, and state and private suppression of the political left.

While the processes of primeval emergence and organization of this next fascism are inchoate, contradictory, and subject to advances and retreats over the next years, they have been established. Nestled in the systemic, structural failures of capitalism and its ideological spew, these mutations will likely multiply, take deeper root in all levels of society, and offer only barbaric solutions to the unfolding crises yet to come.

Opening the door to neo-fascism

Like in previous historical periods, xenophobia, racism, and the repression of migrant and stateless people have been the harbinger of more sinister transformations that manifest in distinct ways within the state apparatus and society. While still in an incipient stage, elements of fascism are revealing themselves. This is happening simultaneously and in tandem within the state and in the social sphere. It is most apparent in the growing autonomy, open racism, violence, and impunity of state-repressive bodies such as ICE and CBP, fascist infiltration into the police and local Republican parties, the growth of violence-oriented extremist networks and their coordination through social media platforms.

Social militarization in the name of “securitization” against migrants and refugees is a trajectory towards authoritarianism, in proportion to an increasing level of class repression. This starts within the immigrant population, but creates the infrastructure and lays the groundwork for generalization. This is observable in the targeting of the political left, the monitoring and suppression of critical media, and most recently, the emergence of overtly fascist elements operating within the state bureaucracy. Furthermore, agencies like ICE have transcended the supposed “rule of law”, and are acting in an extra-legal manner targeting and disappearing people based on racial characteristics, including profiled citizens, and the parallel operation of violent groups and individuals that act as enforcers by targeting all people who appear Mexican and Central American, especially.

It also reveals how “anti-migration” has become the universal call to action for the international right, which is currently fusing elements of the petty and big bourgeoisies within nation states. Both of these otherwise contradictory elements, dependency on migrant labor alongside xenophobic reaction against it, now occupy much of the space of bourgeois political discourse amidst a growing crisis of functionality of capitalism and a crisis of legitimacy of capitalist ideology.

Trump took the initiative to publicly repudiate the Global Pact on Migration and has since dedicated much of his administration’s energy towards turning ever possible punitive and restrictive screw to inflict as much harm, pain, cruelty, and difficulty on migrants and refugees as possible within the existing repressive framework. But he did not create this framework.

Successive US administrations have been constructing the juggernaut of repression in harmonious succession since the administration of Jimmy Carter. Nevertheless, Trumpism constitutes both an impetus and reverberation of a new international political current that offers a defense of crisis capitalism by making a hard-right political turn against the world’s migrant and stateless people.

Racist xenophobia intertwined through an orchestrated criminalization of statelessness is the undercurrent of this phenomenon. It is currently expressing itself internationally in various capacity-building articulations. These include quasi- and certified fascist political movements and parties. In the United States, is also being expressed through the formation and evolution of migrant-specific institutions of repression such as Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE).

Like in past iterations of fascism, reactionary nationalism and the various ideological expressions of racism that are a by-product of imperialism are the twin driving forces behind the repression of migrants and refugees. This includes virulent and pervasive Islamophobia and anti-blackness embedded in the opposition to migration specifically from the Middle East and Africa, and the racialized, anti-indigenous, and anti-black content of opposition to immigration from south of the US border and the Caribbean.

Also, like in the past, this is occurring in the context of a prolonged crisis of capitalism, albeit in new forms. Lastly, it also occurs within the context of rising inequality and a surge in revolutionary energy and class struggle on an international scale.

As international capitalist integration increases, it simultaneously produces a heightened transnational sensitivity to class struggle elsewhere. This produces repressive impulses that then blow back within the centers of empire. Repression abroad extends to repression at the center, especially as inequality and class polarization widen and begin cleaving apart the efficacy of the ruling-class consensus that governs from the heart of empire. In regards to policing the working class, the functions of migrant repression and enforcement are evolving and transcending the boundaries of citizenship—affecting the class as a whole.

The trajectory of anti-migration politics now afflicts societies both at the center and at secondary concentric rings of the global capitalist system. The accumulation and consolidation of forces of the far right expresses itself with both general and specific features. The political center in bourgeois capitalist societies are sliding in unison from variations of conservatism towards degrees of authoritarianism. In some countries, there are more overt expressions of neo-fascism emerging.

These emerging forces of the Right are also militant stewards of unfettered capitalism on behalf of their own ruling classes. While they may align across borders against their ideological opponents, they are also in fierce competition with one another. The coalescing of the far-right and neo-fascist forces internationally is an ephemeral phase of international capacity-building that is fraught with many contradictions—and will ultimately unwind into an inevitable factionalization inherent in capitalist competition. In the meantime, it serves to temporarily align forces that are seeking to reorganize their own governance models, legal frameworks, and militarization projects in anticipation of a long and uncertain future of intensified inter-imperialists conflict, international class struggle, and cycles of revolution and counter-revolution.

The anti-migrant international

Trump and the anti-migrant edifice in the US wasn’t needed to create like-minded counterparts in other parts of the world. They each have their own organic composition and origin stories. But like the so-called “War on Terror”, the operations of US empire have had a resounding and reordering effect on the rest of the world, especially within the political topography of reactionary nationalism and the far right. Furthermore, anti-migration as an instrument of political mobilization has become an international phenomenon, articulating and activating along the concentric nodes of the global capitalist system.

As the principal center of the global capitalist system, ideological and programmatic shifts in the operations of US empire inspire replication internationally, especially when it serves other national capitalist groups in their processes of accumulation, class control, containment or elimination of oppositional forces.

Through imperialist relationships, where the US has the disproportionate power to impose or suffuse its own military operations or operational models, it has created a webbing of migrant control and suppression that span the globe. Agents with the International Operations Division of ICE, for instance, serve as “liaisons to governments and law enforcement agencies across the globe and work side-by-side with foreign law enforcement on HSI investigations overseas.” ICE has spread around the world, with jurisdictions closely aligned to military positions in over 70 countries and within every region. Agents operate out of military bases and infrastructure, and are stationed at international airports and other strategic locations.

In some cases, compliant regimes like those in Guatemala, Honduras, and El Salvador have allowed ICE and Customs and Border Patrol agents and operations to extend into their national territory to integrate into their police forces or train personnel directly. In Mexico, the government has agreed to act in conjunction as an auxiliary to US efforts to repress and control migration for its own purposes.

These arrangements are made possible and facilitated through unequal relations long-established by imperialist domination. For example, aid to these Central American nations were cut prior to this new set of agreements, as a means of heavy-handed insurance that restoration was contingent on compliance. For Mexico, the US had previously traded military aid to encourage compliance with its plans for regional security integration.

When Andres Lopez Manuel Obrador was elected, replacing the acquiescent regime of Enrique Peña Nieto, the Trump threaten to raise tariffs on Mexican-made goods as reprisal if US diktats on migration-control within that country were not followed. This successfully bullied the timorous Mexican capitalist class, which in turn cajoled the state to comply.

Other capitalist nations have also followed suit by initiating their own anti-migrant campaigns. In different corners of the globe, rightwing capitalist parties and far-right demagogues that have attained, held, or maintained some form of state power through anti-migrant campaigning in recent years.

In Europe, anti-migrant parties have taken the reins of government in Italy, Sweden, Austria, Hungary, Poland, and won regional elections in Germany and Spain. Support for anti-immigrant parties in general has doubled in 13 European countries from 12.5% in January 2013 to 25% in September 2018. In the most recent European Union election, far-right anti-migration parties won a mean average of 18.23% of the total combined vote across 17 nations.

Far-right and neo-fascist groupings have formed their own European-wide political party called Identity and Democracy (ID) consisting of far-right anti-migrant parties from nine countries led by Matteo Salvini’s League party (Lega) in Italy, Marine Le Pen’s National Rally in France, and the Alternative for Germany (AfD). In the last European Parliamentary election in June, this group won 10% (73 of 751) seats campaigning explicitly for “more restrictive refugee and asylum policies [and] more spending on EU external border controls[.]” The articulation of far-right forces is the fastest growing trend in European politics.[4]

The advance of the far-right by campaigning for migrant repression has ideologically disarmed centrist and center-left political rivals. Many of these same political parties are being pulled further to the right as migrant repression becomes more integral to the functioning of capitalist accumulation in the current period. A deep-seated and inextricable allegiance to the capitalist system pulls them in tow as the systemic poles shift.

These parties have generally led or played a supporting role in managing the state and economy in their respective countries over the last four decades. In power they have presided over or supported neoliberal restructuring domestically and abroad. As migrant repression has become a neoliberal growth industry—both as an instrument of wage suppression and a commodity for the prison, arms, tech, and surveillance sectors—they have been complicit as political actors.

The Democrats in the US, Liberals and most Social Democrats in Europe, and their ideological counterparts in other parts of the world, continue to stubbornly adhere to the model of neoliberal capitalism as the only conceivable path forward. This continues even as social inequality spirals towards unprecedented levels, and austerity undermines the social safety net, ravages the poor, and eats away at the stability for even the middle classes. Incapable of presenting an alternative, they have come to see and present themselves as the best-equipped stewards to navigate capitalism through the latest crisis. While they use different vocabularies and present themselves as more humane, centrist and center-left parties have been shifting to the right as part of the general terrain of bourgeois politics.

In late 2018 the international political heavyweights of centrism led by Hillary Clinton, Tony Blair, and Matteo Renzi, united to stake out and showcase their own positions as part of a tour across Europe. This uninspiring response to the far right amounted to a general accommodation to the right’s narrative. Twisting in the wind, they wrongfully concluding that if common people are accepting right-wing ideas, then so should the center and center left.

Former British Labor Party Tony Blair stated that “those on the center ground had to accept immigration was an issue of concern to large swathes of the electorate that cannot just be ignored.” Former Democratic Party Prime Minister of Italy critiqued the rise of the far-right in his own country, but played a major role in the crack-down on migrants in refugees during his term in office. A little over a year earlier, he led a campaign to reduce the number of refugees entering Italy, claiming “[w]e need to free ourselves from a sense of guilt. We do not have the moral duty to welcome into Italy people who are worse off than ourselves.” The anti-immigrant leader of the far-right Lega Party, Matteo Salvini responded: “Thanks for all the work. We will take it…They [the Democratic Party] chatter and get embarrassed about it, while we can’t wait to actually do it.” They were elected into power a year later.

For her part, Hillary Clinton used the tour to blast her counterparts for being too soft on migration and to take a harder line to co-opt the far-right’s messaging. “I think Europe needs to get a handle on migration because that is what lit the flame… [that they are] not going to be able to continue to provide refuge and support.” With this as the ideological leadership of the center and center-left, it becomes possible to understand how and why many of these parties are now shifting tack on the issue.

European liberals are increasingly calling for the adoption of restrictive policies as part of their efforts to remain viable in the slide to the right:

Those who, instead, have accepted the need for harder-line migration policies – such as Denmark’s Social Democrats, who this month sidelined their far-right challengers with a much harder line on integration, or Spain’s Socialists, who in April won the largest share of the vote by putting “safe, orderly” immigration at the heart of their platform – have found their way back to power.

The anti-migrant international movement has been successful in shifting policy and discourse on a global scale. This becomes especially apparent in the intensification of the scale of intra-national and generalized social violence against migrants and refugees over the last few years.

Intranational violence: states versus stateless people

As previously noted, the United States sets the standard in many ways for state violence against migrants and refugees. Successive US presidents since Bill Clinton have walled-off large sectors of the US-Mexico border since 1994, re-routing migration through vast and deadly mountainous and desert terrain has led to the death and disappearance of over 8,000 migrants and refugees.

Within his first two years in office, Trump’s administration implemented the notorious “zero-tolerance policy” of separating and incarcerating thousands of migrant families at the border. He then changed the rules for refugees, arresting all who applied for status between April and September 2019, corralling over 270,000 men, women, and children into Border Patrol stations, makeshift detention centers, and open-air prisons that have the characteristics of concentration camps.

Trump has since closed the door to asylum-seekers at the southern border, requiring them to stay in Mexico pending an intentionally prolonged review process. This has stranded thousands of people in squalid camps and tent-cities along the southern side of the border. Several people have recently died while desperately trying to cross to escape the extreme conditions. The list of atrocities goes on, not only in the US, but internationally.

Australia’s ruling rightwing Liberal Party has campaigned on opposing migration, closing access for refugees, and overt Islamophobia. More than 95,000 people have sought asylum in Australia by plain over the past five years, yet 84% had their claims rejected. Arrival by boat, the method for the poorest and most desperate refugees and migrants, has been forbidden since 2013.

More than 3,000 people who have arrived through this method have been sent to offshore detention centers in Nauru and Manus Island. According to UN High Commissioner for Human Rights Michelle Bachelet, refugees forced into these camps have been “subjected to prolonged, indefinite and effectively unreviewable confinement.” The deplorable conditions in these concentration camps have led to multiple cases of suicide and widespread psychological trauma.

The brutal state repression of migrants and refugees in Australia has pushed mainstream political discourse to the far-right, creating the conditions for a dramatic resurgence of white nationalist and neo-nazi activity. There has been a predictable surge in racially-motivated attacks and hate crimes in correlation with the toxic political environment, although the national police rarely prosecute such offenses or treat them as politically motivated.

In India, the far-right ruling Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) party has wielded the anti-migrant cudgel in an effort to ethnically-cleanse almost two million people in the far northeastern border state of Assam. As part of their 2019 re-election campaign, the Hindu-chauvinist party echoed Trump’s attack on Mexicans and Central Americas, claiming that Muslim “infiltrators” were crossing India’s borders as undocumented immigrants and refugees.

Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi has stated his intention create a National Registry of Citizens (NRC). Beginning in Assam, the BJP intends to revoke the citizenship of the Muslim population who cannot provide evidence family residence in the state going back 50 years. The ruling party has also begun construction of detention camps to roundup and incarcerate those declared “illegal.” To make the point clear, BJP President Amit Shah declared during election campaigning that “[t]hese infiltrators are eating away at our country like termites…The NRC is our means of removing them.” Amidst this unfolding human rights crisis, the Trump Administration invited Modi to the US and publicly regaled him for his efforts to “unite” India.

In other parts of Asia, ruling groups have also utilized and politicized the anti-migration concept of citizenship controls and exclusions, and the attendant xenophobia and racism, as an instrument of governance for their own purposes. This includes Myanmar’s ethnic-cleansing of the Rohingya, and China’s mass-detention of Uighur people.

The repression of migrants is not new in Italy, but it has taken a qualitatively more violent and deadly form with the victory of the neofascist Lega Party since June of 2018. As a junior partner of the centrist “Five Star Movement”, the Lega gained prominent positions within the government as part of a power-sharing agreement, including the Ministry of the Interior (which oversees migration policy). In their election, they enjoyed the direct backing and support of the Trump Administration, claiming their campaign was inspired by Trump’s crackdown in the US.

The Lega has set an aggressive agenda to close off Italian ports in the Mediterranean to migration and refugee access from Africa, deployed interception operations, and turned away thousands. Furthermore, they have criminalized humanitarian migrant rescue operations. This militarization of the sea has made crossing for migrants more desperate, precarious, and clandestine. The result has been catastrophic, contributing to the deaths of at least a thousand refugees since the beginning of 2019. Over 19,000 migrants and refugees have been reported dead or missing attempting to cross into Italy other points of entry since October 3, 2013.

The Lega has also shut down various migrant reception centers within the country and enacted a comprehensive package of decrees to repress the rights and free movement of migrants in the interior. These greatly reduce access to refugee protections, expedite deportations, and cut access to social programs and services. Predictably, these refugee bans have presaged a dramatic rise in racist attacks and hate-crimes.

Amidst a severe economic crisis in Turkey, the Erdogan government has publicly announced campaign to deport over a million undocumented Syrian refugees. This campaign has begun with the deportation of LGBTQ+ refugees and political radicals and dissidents. Over 3.5 million Syrian have crossed the border turkey since 2011, with most integrating into the low-wage sectors of working class and many without formal authorization. The government is now treating them as a scapegoat for the economic crisis, and pursuing a path of repression similar to the established US model beginning with criminalization and low-scale deportations:

Officials are cracking down on Syrians working illegally or without residence papers, fining employers and forcing factories and workshops to close. Pro-government media have grown more critical of Syrians, landlords are raising their rents, and social media is bursting with anti-Syrian comments…Syrian workers were being told to acquire work permits and pay social security, he said, but many say they cannot afford the extra costs, and even if they can, they fear more rules will be enforced, including one that demands five Turkish citizens have to be employed for every Syrian in a company.

While not an exhaustive list, there is a growing trend of state violence against stateless people carried out by far-right governments in different regions of the world. This has been enabled and facilitated by an ongoing crisis of extreme social inequality, displacement, and instability; the functionality of migrant repression as a pillar of capitalist accumulation in the global and regional centers of capitalism, and the qualitative rise of categorically far-right regimes who criminalize migrants to further exploit the issue for political gain.

The international criminalization of migrants and refugees, their capitalist exploitation as a marginalized sections of the global working classes, and the growth of the far-right and neo-fascism have not been met with a substantial opposition movement or alternative vision for alleviating the economic crisis driving migration and inequality. In a companion piece to follow this one, I will argue that a counter international needs be constructed on the basis of opposing border restrictions and supporting free movement of people, organizing unions and solidarity across national boundaries, and building an explicitly anti-capitalist political movement.

Notes:

[1] There are a variety of other economic factors driving out-migration, including (but not limited to) IMF-imposed austerity and structural adjustment policies downsizing the economy, the propensity for jobs to pay low-wages below the rate of sustenance, especially in foreign-owned sectors like the “maquiladoras” in Mexico and Central America.

[2] I will generally refer to these different categories of displaced people as “migrants” throughout the essay.

[3] Some examples include: The Arab Spring, the Movement of the Squares in Europe, Occupy Wall Street in the US, and other uprisings and revolts in Africa, Asia, and South America

[4] The only exception has been the experience of Golden Dawn, the violent neo-Nazi party that rose to become to third largest party in Greece until recently. See https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2019/07/neo-fascist-golden-dawn-party-crashes-greek-parliament-190708060921804.html

Originally posted at Punto Rojo.

Montpellier, France, Nov. 18, 2019

Montpellier, France, Nov. 18, 2019

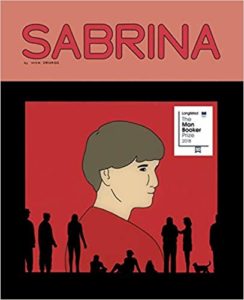

Sabrina, a graphic novel by Nick Drnaso, is the first graphic novel to be long listed for the Man Booker Prize in the award’s long history. It came as a surprise to many of the loyalists of the literary community (those who were also surprised by Bob Dylan’s Nobel Prize nomination) and opened up questions about authenticity of form and the role of literary jury.

Sabrina, a graphic novel by Nick Drnaso, is the first graphic novel to be long listed for the Man Booker Prize in the award’s long history. It came as a surprise to many of the loyalists of the literary community (those who were also surprised by Bob Dylan’s Nobel Prize nomination) and opened up questions about authenticity of form and the role of literary jury.

Resistance to the Indonesian government continues in West Papua, and it has a history.

Resistance to the Indonesian government continues in West Papua, and it has a history.

Remember when the Berlin Wall came down? I do.

Remember when the Berlin Wall came down? I do.

Over the past few days a popular uprising has broken out across Idlib against the hardline Islamist group HTS (formerly Al-Qaeda linked Nusra) which is militarily dominant in much of the province.

Over the past few days a popular uprising has broken out across Idlib against the hardline Islamist group HTS (formerly Al-Qaeda linked Nusra) which is militarily dominant in much of the province.

The coup d’état against Bolivian president Evo Morales has generated the kind of anguish that great defeats of revolutionary struggles evoke: Allende’s fall, Che’s death in combat, defeat in the Spanish Civil War. “

The coup d’état against Bolivian president Evo Morales has generated the kind of anguish that great defeats of revolutionary struggles evoke: Allende’s fall, Che’s death in combat, defeat in the Spanish Civil War. “

On Veterans Day this year, in a nation now reflexively thankful for military service of all kinds, nearly 500,000 former service members are not included in our official expressions of gratitude.

On Veterans Day this year, in a nation now reflexively thankful for military service of all kinds, nearly 500,000 former service members are not included in our official expressions of gratitude.

Most news sources are construing or minimizing the Lebanon uprising by claiming

Most news sources are construing or minimizing the Lebanon uprising by claiming

In early December of 2017 the Trump Administration officially withdrew the United States from the UN Global Pact on Migration,

In early December of 2017 the Trump Administration officially withdrew the United States from the UN Global Pact on Migration,

As Turkey starts a full-scale military invasion of northern Syria to crush the Kurdish struggle for self-determination and push Syrian refugees into a zone under its control, it has become clear that no global or regional power is interested in the emancipation of the Kurds or any other peoples of the region. The current ominous situation demands a new kind of dialogue between socialists in the Middle East and North Africa region. There are over 35 million Kurds in Turkey, Syria, Iraq and Iran. The Kurdish struggle for self-determination has been an integral part of the history of the Modern Middle East. Yet authoritarian capitalist and imperialist powers have always used racism, ethnic divisions, sexism and the pull of capital to prevent the creation of a united regional revolutionary and socialist emancipatory movement.

As Turkey starts a full-scale military invasion of northern Syria to crush the Kurdish struggle for self-determination and push Syrian refugees into a zone under its control, it has become clear that no global or regional power is interested in the emancipation of the Kurds or any other peoples of the region. The current ominous situation demands a new kind of dialogue between socialists in the Middle East and North Africa region. There are over 35 million Kurds in Turkey, Syria, Iraq and Iran. The Kurdish struggle for self-determination has been an integral part of the history of the Modern Middle East. Yet authoritarian capitalist and imperialist powers have always used racism, ethnic divisions, sexism and the pull of capital to prevent the creation of a united regional revolutionary and socialist emancipatory movement.

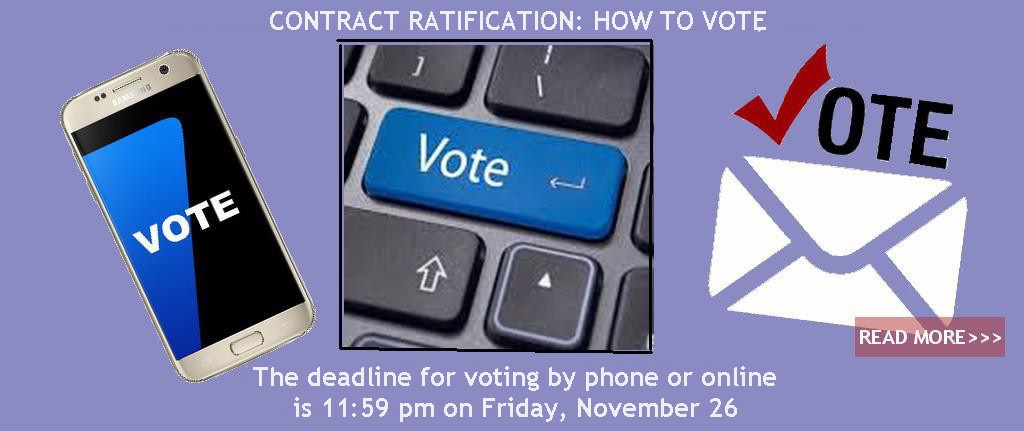

A harsh reality of teachers’ strikes is that they hit parents – moms especially, who still do most of the work of caring for kids and housework – the hardest. Parents are left frantically searching for childcare options, especially if they support their families in low-wage jobs that pay hourly. Missed work means exhausting stress and financial hardship. At the same time school workers, teachers and especially paraprofessionals, who earn poverty wages themselves, feel the pain of lost wages and the uncertainty of what awaits when they return from their struggle to defend conditions for students, as many refer to them, “their kids.”

A harsh reality of teachers’ strikes is that they hit parents – moms especially, who still do most of the work of caring for kids and housework – the hardest. Parents are left frantically searching for childcare options, especially if they support their families in low-wage jobs that pay hourly. Missed work means exhausting stress and financial hardship. At the same time school workers, teachers and especially paraprofessionals, who earn poverty wages themselves, feel the pain of lost wages and the uncertainty of what awaits when they return from their struggle to defend conditions for students, as many refer to them, “their kids.”

Greg Shupak and I, as he notes, differ on one key interpretation of U.S. intervention in Syria. For him, the U.S. intervention, as it shifted its focus to defeating ISIS, never meant a shift away from an anti-Assad stance; rather, it was another means to pursue it. In his analysis, the U.S. control over a vast swath of Eastern Syria, in coordination with the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF), would be used in the future as a means to toppling or weakening the Assad regime. He sees the continued presence of U.S. military bases in Syria, following the defeat of ISIS, as a signal of the Washington’s deep commitments to such a goal. Shupak’s specific ideas of how this might be achieved are not totally clear (not that this is required, considering how unpredictable turns of events in Syria can be). But many others who share a view that the U.S. intervention in Eastern Syria has an end goal of holding onto some control in the country assert that weakening the government would be achieved by some kind of support for an autonomous region in Eastern Syria, in coordination with the SDF.

Greg Shupak and I, as he notes, differ on one key interpretation of U.S. intervention in Syria. For him, the U.S. intervention, as it shifted its focus to defeating ISIS, never meant a shift away from an anti-Assad stance; rather, it was another means to pursue it. In his analysis, the U.S. control over a vast swath of Eastern Syria, in coordination with the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF), would be used in the future as a means to toppling or weakening the Assad regime. He sees the continued presence of U.S. military bases in Syria, following the defeat of ISIS, as a signal of the Washington’s deep commitments to such a goal. Shupak’s specific ideas of how this might be achieved are not totally clear (not that this is required, considering how unpredictable turns of events in Syria can be). But many others who share a view that the U.S. intervention in Eastern Syria has an end goal of holding onto some control in the country assert that weakening the government would be achieved by some kind of support for an autonomous region in Eastern Syria, in coordination with the SDF.

In “

In “