Gilbert Achcar is a Professor of Development Studies and International Relations at SOAS University of London. He is the author of numerous books on the Middle East, including The People Want: A Radical Exploration of the Arab Uprising and Morbid Symptoms: Relapse in the Arab Uprising. He was interviewed for the Marxist Left Review by Darren Roso.

Gilbert Achcar is a Professor of Development Studies and International Relations at SOAS University of London. He is the author of numerous books on the Middle East, including The People Want: A Radical Exploration of the Arab Uprising and Morbid Symptoms: Relapse in the Arab Uprising. He was interviewed for the Marxist Left Review by Darren Roso.

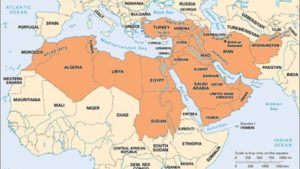

Let’s start by returning to what now seems to be a distant memory: the revolutionary shockwave that swept the Arab world in 2011. You argued in your book, The People Want: A Radical Exploration of the Arab Uprising, that these events were only the beginning of a protracted revolutionary process owing to the specific nature of capitalism in the Middle East. Could you explain these dynamics of political economy in the Arab world and their relationship to forms of authoritarian rule?

To begin with a general consideration, it is obvious now that we are witnessing a severe global crisis of the neoliberal stage of capitalism. Neoliberalism developed as a full-fledged capitalist stage since the enforcement of its economic paradigm in the 1980s. This stage has gone into crisis since the Great Recession a decade ago. The crisis is unfolding under our eyes, resulting in ever increasing social upheavals. If you look today at what is occurring in Chile, Ecuador, Lebanon, Iraq, Iran, Hong Kong and several other countries, it looks like the boiling point is reached by more and more countries.

The events in the Arab region fit into that general global crisis, to be sure. But there is something specific about that regional upheaval. There, the neoliberal reforms were carried out in a context dominated by a specific type of capitalism – a type determined by the specific nature of the regional state system that is characterised by a combination in various proportions of rentierism and patrimonialism, or neopatrimonialism. What is mostly specific to the region is the high concentration of fully patrimonial states, a concentration unequalled in any other part of the world. Patrimonialism means that ruling families own the state, whether they own it by law under absolutist conditions or just in fact. These families regard the state as their private property, and the armed forces – especially the elite armed apparatuses – as their private guard. These features explain why the neoliberal reforms got their worst economic results in the Arab region of all parts of the world. Neoliberal-inspired changes achieved in the region resulted in the slowest rates of economic growth of any part of the developing world and, consequently, the highest rates of unemployment in the world – specifically youth unemployment.

The reason for this is not difficult to understand: the neoliberal dogma is based on the primacy of the private sector, the idea that the private sector should be the driving force of development, while the state’s social and economic functions must be curtailed. The dogma says in a nutshell: introduce austerity measures, trim the state down, cut social expenditure, privatise state enterprises and leave the door wide open to private enterprise and free trade, and miracles will happen.

Now, in a context lacking the prerequisites of ideal-typical capitalism, starting with the rule of law and predictability (without which long-term developmental private investment cannot happen), what you end up getting is most of private investment going into quick profit and speculation, especially in real estate along with construction, but not in manufacturing or agriculture, not in the key productive sectors.

This created a structural blockage of development. Thus, the general crisis of the global neoliberal order goes in the Arab region beyond a crisis of neoliberalism into a structural crisis of the type of capitalism prevailing there. There is therefore no way out of the crisis in the region by a mere change of economic policies within the continued framework of the existing kind of states. A radical mutation of the whole social and political structure is indispensable, short of which there will be no end in sight to the acute social-economic crisis and destabilisation that affects the whole region.

That’s why such an impressive revolutionary shockwave rocked the whole region in 2011, rather than just mass protests. The prospect was truly insurrectionary, with people chanting “The people want to overthrow the regime!” – the slogan that has become ubiquitous in the region since 2011. The first revolutionary shockwave of that year forcefully shook the regional system of states, revealing that it had entered a terminal crisis. The old system is irreversibly dying but the new cannot be born yet – I’m referring here, of course, to Gramsci’s famous sentence – and that’s when “morbid symptoms” start appearing. I used that phrase in the title of the 2016 sequel to my 2013 The People Want.

Is it true to say that neoliberal measures in the Arab world have accelerated despite the revolutionary surge? Egypt’s food prices are rising along with electricity and fuel prices, and the conservative estimates of the World Bank say about 60 percent of Egyptians were “either poor or vulnerable”, all this while the regime has renewed its crackdown on street protesters. Can you talk about the relationship between counter-revolution and accelerated neoliberalism?

Egypt provides a very good example of this, indeed. When the Great Recession hit in 2008, many believed that it heralded the end of neoliberalism and that the pendulum would swing back towards the Keynesian paradigm. That was a huge illusion, however, for the simple reason that economic policies are not determined by intellectual and empirical considerations; they are determined instead and above all by the balance of class forces.

The neoliberal turn has been steered since the 1980s by fractions of the capitalist class, those with a vested interest in financialisation. In order to bring a new shift away from that, there needs to be a change in the social balance of forces, impacting the balance between fractions of the capitalist class itself, a change equivalent at least to that which took place in the 1970s and 1980s.

This did not happen yet, and the progressive forces opposed to neoliberalism have not yet proved strong enough to impose change. The neoliberals are still running the show: they claim that the reason of the global crisis is not neoliberalism but the lack of a thorough implementation of its recipes. Although they resorted massively in 2008-9 to measures contradicting their own dogma, such as the huge bailout of the financial sector by means of state funds, they quickly reverted to more and more of the same neoliberal policies pushed further and further.

That’s exactly what we’ve got in the Arab region, despite the gigantic revolutionary shockwave that shook the whole region in 2011. Almost every single Arabic-speaking country saw a massive rise of social protest in 2011. Six of the region’s countries – that is more than a quarter of them – witnessed massive uprisings. And yet, the “lesson” according to the IMF, the World Bank, those guardians of the neoliberal order, is that all this happened because their neoliberal recipes hadn’t been implemented thoroughly enough! The crisis, they claimed, was due to insufficient dismantling of remnants of yesterday’s state-capitalist economies. They asserted that the solution is to end all forms of social subsidies, even more radically than what had already occurred.

However, the reason that governments of the region did not do more of that indeed was because they were afraid to do so. This isn’t Eastern Europe after the fall of the Berlin Wall, when people swallowed the very bitter pill of massive neoliberal changes in the hope that it would bring them capitalist prosperity. In the Arab world, people are not willing to pay the price for that because they have no illusions that their countries will turn out like Western Europe as the Eastern Europeans were brought to believe. Therefore, in order to impose further neoliberal measures on the people, brutal force is required. Egypt is hence a very clear illustration of the fact that the implementation of neoliberalism does not go hand in hand with democracy as Fukuyama’s “end of history” fantasy claimed thirty years ago.

Egypt clearly shows that in order to implement thoroughly the neoliberal program in the Global South, dictatorships are needed. The first such implementation was in Pinochet’s Chile, of course. In Egypt, it is now the post-2013 dictatorship led by Field Marshal Sisi – the most brutally repressive regime that the Egyptians have endured in many decades. It has gone the furthest in implementing the full neoliberal program advocated by the IMF, at a huge cost to the population, with a steep rise in the cost of living, food prices, transport prices, everything. People have been completely devastated. The reason why their anger did not explode in the streets on a massive scale is that they are deterred by state terror. But the full implementation of the IMF’s neoliberal recipes has not and will not produce an economic miracle. Tensions are thus building up and sooner or later the country will erupt again. There was already some limited explosion of popular anger last September; sooner or later, there will be a much bigger one.

Though contexts differ, and specificity is always important, why did barbarism maintain its head start over the workers’ and democratic movements throughout the Arab world? What, and why, were the turning points of defeat in the region since 2011? What is the state of the Egyptian left and the workers’ movement in the face of Sisi’s ultra-neoliberalism and his authoritarian brutality?

Unfortunately, both the left and the workers’ movement in Egypt are in bad shape. They have suffered a painful defeat – not only due to the brutal comeback of the repressive state, but also because of their own contradictions and illusions. The major part of the Egyptian left has pursued a politically erratic trajectory, switching from one misconceived alliance to another: from the Muslim Brotherhood to the military. In 2013, most of the left and the independent workers’ movement supported Sisi’s coup very short-sightedly, subscribing to the illusion that the army would put the democratic process back on track. They thought that getting rid of Morsi and the Muslim Brotherhood, after their year in power, would reopen the way to furthering the revolutionary process even though it was brought about by the military.

It sounds rather silly, but they did genuinely hold this illusion, which the military fostered in the initial post-coup phase. The military even co-opted the head of the independent workers’ movement into their first post-coup government. This terrible blunder discredited the left as well as the independent workers’ movement. As a result, the left-wing opposition is much weakened and marginalised in today’s Egypt.

I’m not speaking here of the Marxist radical left, which has always been marginal, although it played a disproportionate role at times during the revolutionary upheaval of 2011-13. I’m speaking of the broader left, the one that used to appeal to large masses. This broader left has lost much of its credibility after 2013. This is actually one crucial reason why people have not mobilised massively against the new neoliberal onslaught. When there is no credible alternative, people tend to assimilate the regime’s discourse that says: “It’s us or chaos, us or a Syria-like tragedy. You must accept our iron heel. It will be tough, but at the end of the day you will find prosperity”. The Egyptians do not really buy the last promise – prosperity – but they are still paralysed by the fear of falling into a situation much worse still than what they are enduring.

Linked to all that is another specificity of the regional revolutionary process, of which Syria is the most tragic illustration. We already discussed a first specificity – the structural crisis that is peculiar to the Arab world in the context of the general crisis of neoliberalism. The other specificity is that this region has experienced the development over several decades of a reactionary oppositional current, which was promoted for many years by the United States alongside its oldest ally in the region, the Saudi kingdom. I mean Islamic fundamentalism, of course – the whole spectrum of this current, whose most prominent component is the Muslim Brotherhood and whose most radical fringe includes al-Qaeda and the so-called Islamic State (aka ISIS).

Islamic fundamentalism was sponsored by Washington as a main antidote to communism and left-wing nationalism in the Muslim world during the Cold War. During the 1970s, Islamic fundamentalists were green-lighted by almost all Arab governments as a counterweight to left-wing youth radicalisation. With the subsequent ebb of the left-wing wave, they became the most prominent opposition forces tolerated in some countries, such as Egypt or Jordan, and crushed in others such as Syria or Tunisia. They were, however, present everywhere.

When the 2011 uprisings started, Muslim Brotherhood’s branches jumped on the revolutionary bandwagon and tried to hijack it to serve their own political purposes. They were much stronger than whatever left-wing forces remained in the region, very much weakened by the collapse of the USSR, while the fundamentalists enjoyed financial and media backing from Gulf oil monarchies.

As a result, what evolved in the region was not the classical binary opposition of revolution and counter-revolution. It was a triangular situation in which you had, on the one hand, a progressive pole – those groups, parties and networks who initiated the uprisings and represented their dominant aspirations. This pole was organisationally weak, except for Tunisia where a powerful workers’ movement compensated for the weakness of the political left and allowed the uprising in this country to score the first victory in bringing down a president, thus setting off the regional shockwave. On the other hand, there were two counter-revolutionary, deeply reactionary poles: the old regimes, classically representing the main counter-revolutionary force, but also Islamic fundamentalist forces competing with the old regimes and striving to seize power. In this triangular contest, the progressive pole, the revolutionary current, was soon marginalised – not or not only due to organisational and material weakness, but also and primarily because of political weakness, of the lack of strategic vision.

The situation became dominated therefore by the clash between the two counter-revolutionary poles, which escalated into a “clash of barbarisms”, as I call it, of which Syria is the most tragic illustration, with a most barbaric Syrian regime confronting barbaric Islamic fundamentalist forces. The huge progressive potential that was represented by the young people who initiated the uprising in Syria in March 2011 got completely crushed.

Many of these young people left the country, because they couldn’t survive either in regime-held territories or in territories held by Islamic fundamentalist forces. Much of the Syrian progressive potential was thus scattered in Europe, Turkey, Lebanon and Jordan. Some of it survives inside the country but, as long as the war situation lingers on, it will be difficult for it to re-emerge.

The Kurdish situation in Syria is a different story. The Kurdish PYD/YPG in North-East Syria is undoubtedly the most progressive of all the armed forces active on the ground in Syria, if not the only progressive force. They managed to develop and extend the territory under their control with US backing, because Washington under Obama saw them as efficient foot soldiers in the fight against ISIS. They had their own stake in fighting ISIS, of course, since it is a deadly enemy for them. Their first direct cooperation with the US was indeed in the battle of Kobane in 2014, when US air support including airdrops of weapons was decisive in allowing the Kurdish fighters to roll back ISIS’s offensive. There was thus a convergence of interests between the US, providing air support as well as other means and resources, and the YPG, providing troops on the ground.

That is what Donald Trump has let down, stabbing the Kurds in the back and opening the way to Turkey’s colonial-nationalist and racist onslaught against them. Their situation has become extremely precarious as they are now caught between Turkey’s hammer and the Syrian regime’s anvil, between Turkish chauvinism and Arab chauvinism – two projects of ethnic cleansing, converging on the project to replace Kurds with Arabs in Syria’s border areas with Turkey. Moscow is helping both in this endeavour.

But the PYD/YPG failed to join up consistently with the rest of the struggle against Assad’s murderous regime…

I wouldn’t put the main blame on them: none of the Syrian armed opposition forces was open to a true recognition of the Kurds’ democratic and national rights. To be sure, the PYD/YPG are not some reiteration of the Paris Commune as some tend to portray them quite naively. And yet, with all their limitations and without fostering illusions about them, they represent the most progressive significant organised force on the ground in Syria. If we take the status of women as our main criterion – and it should always be a crucial criterion for progressives – there is no match for the PYD/YPG. Add to this that their co-thinkers in Turkey lead the Peoples’ Democratic Party (HPD), the only progressive and feminist major political force in that country.

What were the most significant theoretical and political lessons to draw out of the previous cycle of revolutionary struggle for Marxists? We often hear the argument that Marxism is “Orientalist” and is thus unsuited to non-Western societies. Michel Foucault’s attitude towards the Iranian revolution (1979) was an example of the attempt to find salvation in a non-Western religious Otherness, declaring an end to universal visions of human emancipation, class politics and Marxian theoretical instruments to understand the world.

So why do you believe that Marxist theory is better equipped to make sense of the revolutions and counter-revolutions throughout the Middle East and North Africa? What are the prospects for a new generation of Arabic-speaking Marxist activists to develop since 2011, and to what extent has this started taking place?

The Orientalist vision of the region is that it is doomed to be eternally stuck in religion as part of its cultural essence, and that religion explains everything and has always been the key motivation of the region’s populations. That is a completely flawed vision, of course, which is also very impressionistic in that it ignores the past and believes that the present is going to last forever.

Looking at the Middle East and North Africa in recent years, one may get indeed the impression that Islamic fundamentalist forces are prominent everywhere. However, that wasn’t the case a few decades ago, especially in the 1950s and 1960s, when these forces were marginalised by much stronger left-wing forces. I was asked to write a preface to the re-edition of Maxime Rodinson’s Marxism and the Muslim World a few years ago. This collection of articles, most of which were written in the 1960s, discusses a part of the world where left-wing currents were dominant. I had therefore to inform or remind the readers of this historical fact, lest they be bewildered in reading the book.

Few realise today that in the 1950s and 1960s, it was widely assumed that the Arab region was under communist ideological hegemony. A Moroccan author published in 1967, in French, a book entitled Contemporary Arab Ideology, where he discussed what he called “objective Marxism” as an ideology that was diffuse in the region. By this phrase, he meant that people used Marxist categories and ideas, most of them without even being aware of their origin.

Or take a country like Iraq – a good example. Today, clerics and mullahs dominate the political scene, especially among the Shiites. But if you fast backward to the late 1950s, you’ll find that the major struggle in the country opposed Communists to Baathists, the latter subscribing to a nationalist ideology that described itself as socialist. The Communists were particularly influential among the Shiites and were able to mobilise hundreds of thousands of people in demonstrations. So, think of that Iraq and of today’s Iraq: a wide gulf is separating them. But it proves that there is nothing in the genes of the region’s populations that dooms them to abide by the political guidance of religious forces.

The most popular political leader in modern Arab history was indisputably Gamal Abdel-Nasser – Egypt’s president between 1956 and his untimely death in 1970. He went as far to the left as possible within the boundaries of bourgeois nationalism, implementing a sweeping nationalisation of the economy along with successive agrarian reforms, promoting state-led industrial development, and bringing a substantial improvement in labour conditions, all this on an anti-imperialist and anti-Zionist backdrop.

Although it occurred under harsh dictatorial conditions, this was a very progressive phase in Egypt’s history, and it was emulated in several Arab countries. When you contemplate that history, you realise that the role of Islamic fundamentalism in recent decades is not rooted in some cultural essence, as the Orientalist view would have it. It is rather the product of specific historical developments. As we discussed already, it is partly the product of Washington’s protracted and intensive use of Islamic fundamentalism in cahoots with the most reactionary state on earth, the Saudi kingdom, in fighting Nasser and the USSR’s influence in the Arab region and the Muslim world.

When the Arab Spring (as the uprisings were called in 2011) blossomed, a new generation entered the struggle on a mass scale. The bulk of this new generation aspires to a radical progressive transformation. They aspire to better social conditions, freedom, democracy, social justice, equality, including gender emancipation. They reject neoliberal policies and dream of a society in sharp contrast with the programmatic views of those Islamic fundamentalist forces that hijacked or tried to hijack the uprisings and lead them towards their own goals.

There is a huge progressive potential in the region, and we have seen it coming back to the fore in the second revolutionary shockwave that is presently unfolding. It started in December 2018 with the Sudanese uprising, followed since last February by the Algerian uprising, and since October by massive social and political protests in Iraq and in Lebanon. Sudan, Algeria, Iraq and Lebanon are boiling, and all other countries of the region are on the brink of explosion.

What about the role of Stalinism in the Arab world?

The Soviet Union and the communist parties under its leadership have represented the dominant form of “Marxism” in the region for decades. There have been several important communist parties in the region, all narrowly linked to Moscow. This meant that the self-described Marxist literature was heavily dominated by Stalinism in the region in the 1950s and 1960s. With the global emergence of the New Left in the late 1960s and the 1970s, new translations allowed access to critical Marxist and anti-Stalinist Marxist authors in Arabic.

The rise of a New Left in the Arab region was boosted by the June 1967 defeat of the Arab armies in the so-called Six-Day War, which dealt a major blow to Nasser and his regime. A large section of the youth got radicalised beyond both Nasserism and Stalinism, into what often was radical nationalism in a “Marxist” garb rather than plain Marxism. The Arab New Left grew significantly in the late 1960s and early 1970s, but it failed in building an alternative to the old left, let alone an alternative to the powers that be.

That is the period when the regimes used Islamic fundamentalism to nip the New Left in the bud. Most, if not all, Arab governments unleashed and helped Islamic fundamentalist groups in the 1970s, especially in the universities, as an antidote to the new left-wing radicalisation. They thus contributed significantly to the failure of the radical left.

Of course, the latter bears the main responsibility for its own defeat. It lacked political maturity and strategic acumen. The new radicalisation did not go far beyond previously dominant superficial and dogmatic “Marxism”, heavily influenced by Stalinism. Marxism was generally reduced to a few clichés. There were exceptions, of course, but overall original Marxist intellectual production in Arabic remained very limited – leaving aside contributions by Marxist thinkers from the region who lived abroad and wrote in European languages, such as the late Samir Amin. The most prominent exception was Hassan Hamdan, know under the pen name of Mahdi Amel. He was the most sophisticated intellectual of the Lebanese Communist Party and was assassinated by Hezbollah in 1987. An anthology of his writings will come out soon in English translation.

Let’s return to the present: the Algerian uprising and Sudan’s revolution reignited hope, as have the courageous protests in Egyptian streets and Lebanon’s assemblies in Riad al-Solh square calling to topple the current regime. At the risk of asking an impossible question, to what extent have ordinary people in the region learnt political lessons from the earlier wave of struggle? What kind of mass dynamic is involved here? How have the oppressed and exploited learnt through the experience of mass struggle? Have they learnt?

They have definitely learnt. Protracted revolutionary processes are cumulative in terms of experience and know-how. They are learning curves. The peoples learn, the mass movements learn, the revolutionaries learn, and the reactionaries learn as well, of course, everybody learns. A long-term revolutionary process is a succession of waves of upsurges and counter-revolutionary backlashes – but they are not mere repetitions of similar patterns. The process is not circular, it has to move forward or else it degenerates.

People grasp the lessons of previous experiences and do their best not to repeat the same errors or fall into the same traps. This is very clear in the case of Sudan, but also for Algeria and now for Iraq and Lebanon too. Sudan and Algeria, along with Egypt, are the three countries of the region where the armed forces constitute the central institution of political rule. Of course, armed apparatuses are the backbones of states in general, but it is direct military rule that is peculiar to these three countries in the Arab region.

Their regimes are not patrimonial. No family owns the state to the point of making whatever they wish of it. The state is rather dominated collegially by the armed forces’ command. These are “neo-patrimonial” regimes: this means that they are characterised by nepotism, cronyism and corruption, but no single family is in full control of the state, which remains institutionally separate from the persons of the rulers. That explains why in the three countries the military ended up getting rid of the president and his entourage in order to safeguard the military regime.

That’s what happened in Egypt in 2011 with the dismissal of Mubarak, and this year in Algeria with the termination of Bouteflika’s presidency, followed by the overthrow of Bashir in Sudan, all three carried out by the military. However, when it happened in Egypt, there were huge popular illusions in the military, which were renewed in 2013 when the military deposed Muslim Brotherhood president Morsi.

These illusions were not reiterated in Sudan or Algeria in 2019. On the contrary, the popular movement in the two countries has been acutely aware that the military constitute the central pillar of the regime that they wish to get rid of. The movement in both countries understands very well that when they chant “The people want to overthrow the regime”, they mean military rule as a whole – not the presidential tip of the iceberg alone. They grasp this very clearly in both Algeria and Sudan, unlike what happened in Egypt previously.

But in Sudan there is more than that difference. There is a leadership that embodies the awareness of the lessons drawn from all previous regional experiences. This is mainly due to the foundation of the Sudanese Professionals Association (SPA), which started in 2016 with teachers, journalists, doctors and other professionals organising an underground network. As the uprising that started in December 2018 unfolded, the association developed into a much larger network involving workers’ unions of all key sectors of the working class. It has been playing the central role in the events on the side of the popular movement. The SPA was also instrumental in the constitution of a broad political coalition involving several parties and groups. They are presently engaged in a political tug of war with the military. They agreed temporarily on a compromise that instituted what can be described as a situation of dual power. The country is ruled by a council in which the leadership of the people’s movement is represented alongside the military command. This is an uneasy transitional period that can’t last very long. Sooner or later, one of the two powers will have to prevail over the other.

But the key point here is that the Sudanese experience represents a massive step forward compared with everything we have seen since 2011, and this is thanks to the existence of a politically astute leadership. The SPA didn’t foster any illusions about the military. They are as radically opposed to military rule as they are to Islamic fundamentalism, especially that both were represented in the regime under Omar al-Bashir. They uphold a very progressive program, including a remarkable feminist dimension. This is a very important experience which is very closely observed all over the region.

The popular movement in Algeria is amazing for having been staging huge mass demonstrations every week for several months now. But it has no recognised and legitimate leadership. Nobody can claim to speak in its name. This is an obvious weakness, in stark contrast with Sudan. The forms of leadership naturally change over time, but we haven’t entered some postmodern age of “leaderless revolutions” as some want us to believe. The lack of leadership is a crucial impediment: a recognised leadership is crucial in order to channel the strength of the mass movement towards a political goal. This they have in Sudan, but not in Algeria, and not yet in Iraq or Lebanon.

In both Iraq and Lebanon, however, people inspired by the Sudanese example are trying to set up something like the SPA. There are beginnings in that direction, involving university teachers along with various professionals. In Lebanon, they created an Association of Professional Women and Men, clearly inspired by the Sudanese model. That clearly shows how learning from experience functions at the regional level.

Could you further elaborate about the most significant aspects of the mass movements in Iraq and Lebanon?

Both movements share a remarkable particularity in that both countries, Iraq and Lebanon, are characterised by a sectarian political system.

In Lebanon, it has been institutionalised by French colonialism after World War I in a form close to the country’s present political system. In Iraq, it was established by the US occupation, much more recently. Such sectarian political regimes thrive off sectarian divisions, naturally. In their context, religious sectarian divisions become the defining feature of political life and government. Sectarianism is a very pernicious and effective tool in diverting class struggle into religious strife. It’s an old recipe, a version of “divide and rule”: thwart any horizontal solidarity of class versus class by turning it into a vertical clash between sects. Bourgeois-sectarian nepotistic leaderships secure the allegiance of members of the popular classes belonging to their sectarian community by stoking sectarian divisions and rivalries.

In both Iraq and Lebanon, the accumulation of social grievances resulting from a very wild form of capitalism that crushes ordinary people and deteriorates their standard of living has created a huge resentment. The social explosion was triggered by a political measure in Iraq – the dismissal of a popular military figure – and an economic one in Lebanon – a projected tax on VoIP communications. These measures provoked a formidable outburst of popular anger. In Lebanon, to everybody’s surprise, the outburst covered the whole country and involved people belonging to all sects. In Iraq, it has been mostly confined to the Arab Shiite majority, but this is equally significant since the ruling clique itself is Shiite. The movement in both countries has thus strongly repudiated sectarianism in favour of a renewed sense of popular-national belonging.

In Lebanon, sectarianism was so entrenched historically that it appeared as a very difficult barrier to break. It was therefore very amazing to see people belonging to all religious communities participate in an uprising whose key slogan has become the Arabic equivalent of the Spanish-language “Que se vayan todos!” (All of them must go!), which was the key slogan of the December 2001 popular revolt in Argentina. The Lebanese version says “All of them means all of them” – a way of insisting on the repudiation of all ruling class members, with no exceptions. “Us vs. them” shifted from sect vs. sect to a revolt of the people from below against all members of the ruling caste at the top, whichever religious-political sect they belong to, whether Shiite, Sunni, Christian or Druze.

Hezbollah was not spared – and that is even more striking since a sort of taboo regarding the party, and particularly its leader, had been enforced until then. It was astounding to see that people went into the streets in the regions under Hezbollah’s control despite the party’s clear stance against the popular movement. Since then, there have been successive attempts to intimidate the popular movement by thugs belonging to Hezbollah and its close ally Amal, the two Shiite sectarian groups.

In Iraq, parties and militias linked to the Iranian regime engaged in repressing the popular revolt at a much higher scale, with much killing. That is because Tehran’s tutelage over Iraq’s government is a major target of the popular revolt. The recent explosion of anger within Iran itself was likewise met with brutal repression. Iran’s theocratic regime thus confirms that it is one of the main reactionary forces in the region on a par with its regional rival, the Saudi kingdom. This was already clear from its brutal repression of the democratic popular movement within Iran in 2009 as well as from its massive contribution to the Syrian regime’s counter-revolutionary drive starting in 2013 and from its heavy-handed repression of the social protests that flared up again in Iran at the end of 2017 and early 2018.

The role of women in the second wave of the revolutionary process in the Arab region is another very important feature, and a further indication of the higher degree of maturity achieved by the popular movements. In Sudan, Algeria and Lebanon, women have participated massively and very visibly in the demonstrations and mass rallies as well as in heading them. In the three countries, feminists have been a crucial component of the groups involved in the uprisings. Even in Iraq, where women were hardly visible in the initial stage of the protests, they are getting increasingly involved, especially since the students joined the mobilisation.

The big question now is: will the popular movements in Algeria, Iraq and Lebanon succeed in finding ways to organise, like their Sudanese brothers and sisters did, in order to amplify their struggles’ impact and achieve major steps towards the fulfilment of their goals, or will the ruling classes manage to quell each of these three uprisings and defuse it? Without being optimistic due the very vicious nature of the regimes that govern this part of the world, I have a lot of hope. My hope, however, is based on the knowledge that a huge progressive potential exists, while I am perfectly aware that in order to be realised, a lot of struggle, organisation and political acumen are needed.

This interview originally appeared on Marxist Left Review

After a much contested election process, the largest union of journalists in North America has chosen a 32-year old reporter at the Los Angeles Times to be its new leader, in the U.S. and Canada.

After a much contested election process, the largest union of journalists in North America has chosen a 32-year old reporter at the Los Angeles Times to be its new leader, in the U.S. and Canada.

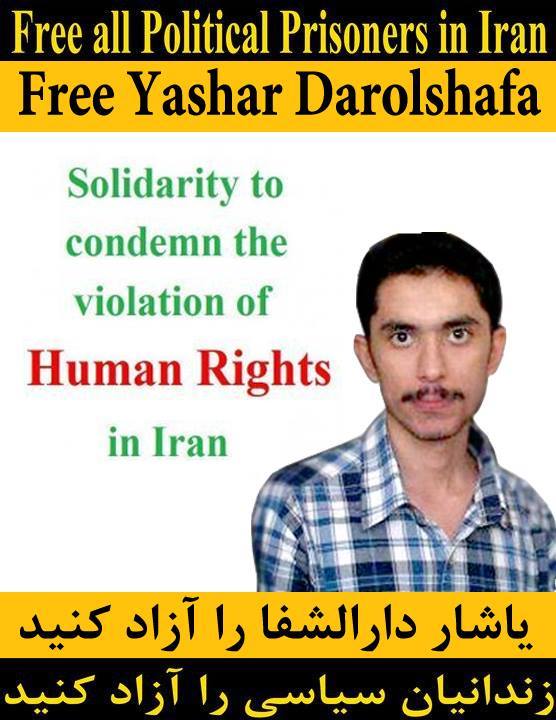

On Thursday November 21, five days after the outbreak of a popular uprising against the Islamic Republic of Iran, Yashar Darolshafa was violently arrested by government authorities at a friend’s home and taken away. Since then, family and friends have not heard from him. Subsequent efforts by family members inquiring about his status, have not led to any results.

On Thursday November 21, five days after the outbreak of a popular uprising against the Islamic Republic of Iran, Yashar Darolshafa was violently arrested by government authorities at a friend’s home and taken away. Since then, family and friends have not heard from him. Subsequent efforts by family members inquiring about his status, have not led to any results.

This is a critical moment in the Middle East and North Africa. In 2019, uprisings have emerged in Sudan, Algeria, Iraq, Lebanon and Iran. All have opposed authoritarianism, neoliberalism, poverty, corruption, religious fundamentalism and sectarianism. Women have been active participants and often in the forefront. The participants are mostly working-class and unemployed youth. They are not content with the ouster of individual ruling figures but want to change the socioeconomic and political system. For all these reasons, the revolts could mark the beginning of a new progressive and revolutionary chapter for the region as a whole.

This is a critical moment in the Middle East and North Africa. In 2019, uprisings have emerged in Sudan, Algeria, Iraq, Lebanon and Iran. All have opposed authoritarianism, neoliberalism, poverty, corruption, religious fundamentalism and sectarianism. Women have been active participants and often in the forefront. The participants are mostly working-class and unemployed youth. They are not content with the ouster of individual ruling figures but want to change the socioeconomic and political system. For all these reasons, the revolts could mark the beginning of a new progressive and revolutionary chapter for the region as a whole.

We in DSA, the Democratic Socialists of America, will have to be able to understand and explain this: Boris Johnson and the Conservative Party won the British general election by a landslide, defeating Labour’s Jeremy Corbyn largely because they broke the “Red Wall” of working class votes in northern Britain’s old industrial region. The region, sometimes compared to the American “rust belt” in the Northeast and Midwest, has seen employment, labor unions, and the standard of living all decline, together with morale. The working class in Britain rejected Corbyn, Labour, and socialism. What does this mean for DSA’s support for Democratic Party candidate Bernie Sanders?

We in DSA, the Democratic Socialists of America, will have to be able to understand and explain this: Boris Johnson and the Conservative Party won the British general election by a landslide, defeating Labour’s Jeremy Corbyn largely because they broke the “Red Wall” of working class votes in northern Britain’s old industrial region. The region, sometimes compared to the American “rust belt” in the Northeast and Midwest, has seen employment, labor unions, and the standard of living all decline, together with morale. The working class in Britain rejected Corbyn, Labour, and socialism. What does this mean for DSA’s support for Democratic Party candidate Bernie Sanders?

The Teamsters for a Democratic Union (TDU) held its 44th annual convention in Chicago in early November, where it

The Teamsters for a Democratic Union (TDU) held its 44th annual convention in Chicago in early November, where it

Noel Ignatiev, the author of the following essay on Frederick Douglass, died on November 9th of this year. Although he had been ill, he wasn’t expecting death in the immediate future. In fact, he was looking forward to the publication of the essay in The Brooklyn Rail. The brief period of time since his death has witnessed a good number of formal obituaries and less formal reminiscences in The New Yorker, Commune, and The New York Times, which provide both biographical facts and descriptions of his impact and influence on students, friends and political comrades. I will try not to repeat too much of what has already been written.

Noel Ignatiev, the author of the following essay on Frederick Douglass, died on November 9th of this year. Although he had been ill, he wasn’t expecting death in the immediate future. In fact, he was looking forward to the publication of the essay in The Brooklyn Rail. The brief period of time since his death has witnessed a good number of formal obituaries and less formal reminiscences in The New Yorker, Commune, and The New York Times, which provide both biographical facts and descriptions of his impact and influence on students, friends and political comrades. I will try not to repeat too much of what has already been written.

Gilbert Achcar is a Professor of Development Studies and International Relations at SOAS University of London. He is the author of numerous books on the Middle East, including The People Want: A Radical Exploration of the Arab Uprising and Morbid Symptoms: Relapse in the Arab Uprising. He was interviewed for the Marxist Left Review by Darren Roso.

Gilbert Achcar is a Professor of Development Studies and International Relations at SOAS University of London. He is the author of numerous books on the Middle East, including The People Want: A Radical Exploration of the Arab Uprising and Morbid Symptoms: Relapse in the Arab Uprising. He was interviewed for the Marxist Left Review by Darren Roso.

The roots of the current social explosion in Chile can be found in the 17-year dictatorship headed by General Augusto Pinochet (1973-1990), who took power after a bloody military coup backed by Washington. The armed forces overthrew the democratic socialist government of Salvador Allende and imposed brutal repression and wrenching neoliberal restructuring. Pinochet and the so-called Chicago Boys privatized pensions, healthcare, education, even the water. The state used violence and terror to subdue and traumatize society, and there was a total absence of justice.

The roots of the current social explosion in Chile can be found in the 17-year dictatorship headed by General Augusto Pinochet (1973-1990), who took power after a bloody military coup backed by Washington. The armed forces overthrew the democratic socialist government of Salvador Allende and imposed brutal repression and wrenching neoliberal restructuring. Pinochet and the so-called Chicago Boys privatized pensions, healthcare, education, even the water. The state used violence and terror to subdue and traumatize society, and there was a total absence of justice.

A

A  Teresa Wright, Popular Protest in China, Polity Press, Cambridge, UK, 2018

Teresa Wright, Popular Protest in China, Polity Press, Cambridge, UK, 2018 Shedding particular light on state management of nationalist protests is Jessica Chen Weiss’ Powerful Patriots, published four years earlier. Such protests have sometimes been a “diplomatic asset” to the regime, providing moral authority in demands on foreign powers. But any upsurge of protest poses an inherent threat in a closed society. The student pro-democracy protests of 1986 and ‘87 that presaged the Tiananmen Square movement were themselves presaged by a wave of anti-Japan protests in 1985—which actually saw students marching on Tiananmen in September of that year. So it isn’t surprising that a new wave of protests over the Diaoyu/Senkaku islands in 1996 was repressed. On the other hand, the 2012 protests over the question were tolerated, as they assisted Beijing in opposing Tokyo’s “nationalization” of the disputed islands. The risk remains, however, that any autonomous mass action could morph from a “tactical asset to strategic liability.”

Shedding particular light on state management of nationalist protests is Jessica Chen Weiss’ Powerful Patriots, published four years earlier. Such protests have sometimes been a “diplomatic asset” to the regime, providing moral authority in demands on foreign powers. But any upsurge of protest poses an inherent threat in a closed society. The student pro-democracy protests of 1986 and ‘87 that presaged the Tiananmen Square movement were themselves presaged by a wave of anti-Japan protests in 1985—which actually saw students marching on Tiananmen in September of that year. So it isn’t surprising that a new wave of protests over the Diaoyu/Senkaku islands in 1996 was repressed. On the other hand, the 2012 protests over the question were tolerated, as they assisted Beijing in opposing Tokyo’s “nationalization” of the disputed islands. The risk remains, however, that any autonomous mass action could morph from a “tactical asset to strategic liability.”

Latin America is experiencing an abrupt change generated by enormous confrontations between the dispossessed and the privileged. This confrontation includes both revolts by the people and reactions by the oppressors.

Latin America is experiencing an abrupt change generated by enormous confrontations between the dispossessed and the privileged. This confrontation includes both revolts by the people and reactions by the oppressors.

“We are protesting against problems in the whole system in general. We reached a crisis where we noticed that the system cannot handle it anymore.”

“We are protesting against problems in the whole system in general. We reached a crisis where we noticed that the system cannot handle it anymore.”

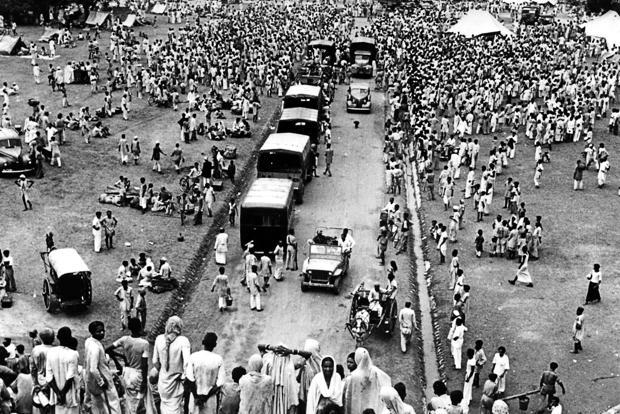

Human beings have been repeatedly subjected to mass displacement and migration due to war, strife and conflict originating on the grounds of religion, race or ethnicity. If a “sneak peak” is taken into the pages of documented human history of mass migration, we will come across scores of refugee crises like World War Two, the Partition of India, the Bangladesh Liberation War, the Venezuelan refugee crisis and notably the current refugee situation in Syria. The quantification of refugees run into millions and embedded within the quantification lies the horror of it.

Human beings have been repeatedly subjected to mass displacement and migration due to war, strife and conflict originating on the grounds of religion, race or ethnicity. If a “sneak peak” is taken into the pages of documented human history of mass migration, we will come across scores of refugee crises like World War Two, the Partition of India, the Bangladesh Liberation War, the Venezuelan refugee crisis and notably the current refugee situation in Syria. The quantification of refugees run into millions and embedded within the quantification lies the horror of it.

(Montpellier, France) On the eve of an “unlimited” (open-ended) General Strike called for Dec. 5, more and more unions and protest groups are pledging join in.

(Montpellier, France) On the eve of an “unlimited” (open-ended) General Strike called for Dec. 5, more and more unions and protest groups are pledging join in.

The

The

Last week, Senator Elizabeth Warren released her

Last week, Senator Elizabeth Warren released her

The idea of the Batman franchise being associated with expressions of popular discontent is something which has already become familiar to us, thanks to Christopher Nolan’s The Dark Knight Rises and the responses it generated, including a much-read

The idea of the Batman franchise being associated with expressions of popular discontent is something which has already become familiar to us, thanks to Christopher Nolan’s The Dark Knight Rises and the responses it generated, including a much-read