As Bashar al-Assad brutally crushes the last areas not under his control, Joseph Daher, Syrian socialist activist, gave this wide-ranging interview to the UK-based journal Socialist Resistance.

As Bashar al-Assad brutally crushes the last areas not under his control, Joseph Daher, Syrian socialist activist, gave this wide-ranging interview to the UK-based journal Socialist Resistance.

Socialist Resistance — The movement for democracy which erupted in 2011 in Syria, alongside others in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA), gave hope that the Syrian people could overthrow the Assad dictatorship. After nine years, there are over 5 million refugees and 500,000 dead. Assad now seems to be on the verge of winning, but what will be left of the country? Can the regime survive?

JOSEPH DAHER – The country has suffered vast damage and widespread destruction, because of Damascus’ war machine, backed by its allies Russia and Iran. Of course other foreign actors contributed to the displacement of the populations and destruction in the country — particularly the military interventions of the US and Turkey and, to a lesser extent, the armed opposition as well as hardline Islamist and jihadist militias.

Additionally, six million Syrians are internally displaced. Around 90 percent of the population live under the poverty line, and more than 11 million people are in need of humanitarian aid inside the country. The cost of reconstruction has been estimated at around$400 billion.

The regime can however survive in the short and mid term with the assistance of Moscow and Teheran. Its resilience does not mean however the end of its contradictions or of dissent, especially in areas held by opposition forces. Despite engaging in repression, the regime still faces challenges, as the reasons that led to the uprising are more than ever present. These include the absence of democracy, and profound socio-economic injustice and inequalities.

These conditions do not necessarily directly translate into political opportunities. No viable organized opposition has appeared. The failures of the opposition in exile and armed opposition groups have left many people who had sympathized with the uprising feeling frustrated and bitter. The absence of a structured, independent, democratic, and inclusive Syrian political opposition, which would have appealed to the poorer classes and social activists, has made it difficult for various sectors of the population to unite and challenge the regime on a national scale.

The latest demonstrations in Sweida against the economic situation and difficult living conditions, an often repeated criticism in many other areas of the country, and the continued protests and clashes in Daraa against the regime’s forces, demonstrate this situation: regional protests without coordination between them.

SR – How did Assad win? For a while he only controlled a small part of the country, the rest being controlled by the democratic forces and ISIS/Daesh. What remains of these democratic forces and of any left progressive movements? What discussion has there been amongst these forces about the course they adopted since 2011?

JD – It was first of all the foreign assistance provided by Iran and Russia (in addition to Hezbollah and other foreign sectarian militias) that has enabled Assad to survive. Then the regime prioritized violence and prevented any opening up to include sections of the opposition or meet demands of the protest movement. In tandem with repression, it mobilized its popular base through sectarian, tribal, regional, and clientelist connections; while portraying the protesters as extremist terrorists or armed gangs seeking to destabilize the country to scare sectors of the society.

Peaceful, non-sectarian, and democratic activists were the main targets of the regime. At the same time, the regime freed significant numbers of Islamic fundamentalist and jihadist personalities with previous military experience from Iraq and other countries, and let them proliferate to realize its own characterization of an uprising led by religious extremists.

The regime also adapted its strategies and tools of repression according to regional variations in sectarian and ethnic composition. The aim of the regime’s high officials was nevertheless consistent: to suppress the protests, divide people according to primordial identities, and instil fear and distrust among them to break the inclusive spirit of the movement. In this perspective, the instrumentalization of sectarian and ethnic differences by the regime was used to divide the popular movement.

The financial assistance given by the regime’s allies, Iran and Russia, allowed it to maintain state institutions and provisions. The state remained the leading employee and provider of resources and services throughout the war. The catastrophic humanitarian and socio-economic situation in Syria, therefore, reinforced the role of the state.

Similarly, the opposition in exile, first represented by the Syrian National Council (SNC) and then by the Coalition, failed to constitute a credible alternative. In both cases, the Muslim Brotherhood (MB), other religious fundamentalists, and sectarian groups and personalities dominated. The players within the SNC and the Coalition believed that the end justified the means, but the end is determined by the means used. This resulted in the absence of an organized democratic or progressive pole on a national level within or outside the country during these years, while letting reactionary Islamic groups occupy the political and military space. This led to a situation where the rhetorical commitments of the opposition in exile to inclusive democracy were not credible enough to persuade large sections of the population to abandon the regime and join the uprising. Further, they were not able to develop any solid and inclusive alternative institutions to the state.

The growth of reactionary Islamic fundamentalist and jihadist forces further reduced the capacities of the protest movement to provide an inclusive and democratic message, including to those who were not involved directly in the events but who sympathized with the uprising’s initial goals. The rise of those Islamic movements had various causes, including the regime’s initial facilitation of their expansion, the repression of the protest movement leading to radicalization among some elements, better organization and discipline, and finally support from foreign countries.

These reactionary forces constituted the second wing of the counterrevolution after the Assad regime. They did not have the same destructive capacities as Assad’s state apparatus, but their outlook on society and the future of Syria stood in complete opposition to the initial objectives of the uprising and its inclusive message for democracy, social justice, and equality. Their policies were equally repulsive to the most conscious sections of the protest movement and threatened religious minorities, women, and many Sunnis who feared their ascension to power because they did not share their view of society and religion. Their ideology, political program, and practices proved to be violent not only against the regime’s forces, but also against democratic and progressive groups, both civilian and armed, and ethnic and religious minorities.

The democratic and progressive forces have been repressed severely in Syria. With the exception of the PYD (Democratic Union Party – Kurdish democratic confederalist political party),which still remains in Syria, most of the groups and activists have been pushed into exile, if not killed and imprisoned.

There has been some discussion looking back at the protest movement among democratic and progressive forces, but it is limited.

One factor that could play a role in shaping future events is the unprecedented documentation of the uprising, including video recordings, testimonials, and other evidence. In the 1970s, Syria saw strong popular and democratic resistance, with significant strikes and demonstrations throughout the country, but this history was not well known by the new generation of protesters in 2011. The revolutionary uprising of 2011, however, with its vast documentary archive, will remain in the popular memory and be a crucial resource for those who resist in the future.

SR – Despite the public knowledge that the people of Syria were confronted with the barbarisms of Assad and ISIS, why was so little, if any, practical support given to the democratic forces?

JD – Indeed, much more could have been done in terms of international solidarity, and the reasons it wasn’t is due to a generalized crisis of the Left. If it used to raise its internationalist flag very high, but you now have sections that are much more nationalistic, taking sides with this or that camp. That’s a direct result of the weakening of class consciousness. And yet all our destinies are linked. Yet the Occupy movement came out of Tahrir Square. And look at the refugee issue and how it is influencing European states — including through the rise of authoritarian and even fascistic parties.

At the same time, you have sections of the Left focusing only on Western imperialism, without trying to learn from popular struggles from the Middle East. They point to their limitations alone, without noticing that these uprisings have shaken the world. In addition to this, some sections of the left refuse to denounce some regional despotic regimes

I however think among small sections of the left, internationalism is still important. Not only in a rhetorical sense, but as a means to learn from certain experiences abroad. This is without forgetting the large participation of progressive and democratic groups and individuals initially in the Syrian uprising, especially in its first years.

SR – What has been the role of the intervention of various foreign countries: Russia and Iran, but also western imperialism? Many on the left opposed western imperialist intervention but were silent on the military support of Russia to Assad. Some even supported him. Why?

JD – The main dynamics of international imperialist and regional interventions were initially motivated by geopolitical considerations rather than economic objectives. Syria was at the centre of many geopolitical games in the region, and its overthrow could change the balance of forces in significant ways. Assad’s regime benefited from these divisions and the assistance given by its allies to This was undoubtedly the most important factor in the resilience of the regime.

Without Russian and Iranian assistance — including Hezbollah and other sectarian militias — the regime would not have been able to sustain itself politically, militarily, and economically. This intervention was key. Even though Russia’s official massive intervention started in 2015, it had troops on the ground before that were aiding the security services. Iranian-backed forces — Hezbollah and others — played a role from 2012.

Today, both countries are interested in benefiting from the spoils of war. Russian companies have been the most successful in this regard.

Iranian and Russian possibilities in Syria were also related to the weakening of US imperialism in the region, especially following its defeat in Iraq, the international financial crisis in 2008, and the uprisings which started at the end of 2010 and beginning of 2011.

Western imperialism, did not want to see a radical change in the status quo vis-à-vis the Syrian regime. This was reflected by the absence of any kind of large, organized, and decisive military assistance by the United States, Western states or both, to the Syrian armed opposition groups. Western governments provided only “nonlethal” support and humanitarian assistance while resisting pleas to arm opposition forces or establish safe zones or no-fly zones.

In addition, the United States opposed supplying various FSA forces with antiaircraft missiles (Manpads) capable of taking down warplanes, which would have curtailed to some extent the murderous and destructive air strikes, particularly at low altitudes. In July 2012, the United States halted the provision of at least 18 Manpads sourced from Libya

The rise of ISIS (Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant) and the establishment of its caliphate in June 2014 following the conquest of Mosul in Iraq pushed Washington to re-engage its forces more deeply in the region. In September 2014, President Obama announced the establishment of a broad international coalition composed of nearly 60 states at its peak, to defeat the jihadist group. However, only a few participated effectively in the campaign in Syria (five states) and Iraq (eight), as the United States conducted approximately 85 percent of its total combat missions in Syria and Iraq in 2015. Washington developed a strategy of “IS first,” with the objective of defeating the group.

This is when in the framework of the strategy of “IS first,” and following the complete failure to assist FSA forces in northern areas, the United States increasingly supported the YPG (People’s Protection Units – Kurdish militia) forces through the coalition known as the SDF (Syrian Democratic Forces), in which the PYD played the leading and dominant role. Washington considered the SDF the most effective fighting force in Syria against IS, although it was not ready to support Kurdish national rights in Syria and elsewhere.

The election of Trump did not change the strategic positioning of Washington over Syria (the priority was still the war on terror and maintaining the structures of the regime), despite a more aggressive and firm policy toward the Assad regime to make it respect the boundaries set by the US administration. Iran’s influence in some regions of Syria was also checked. Washington did not hesitate to bomb the Syrian regime’s military bases or forces on several occasions

Despite the confusion over Trump’s strategy in Syria, US policy did not radically change towards the Assad regime throughout Obama’s and Trump’s early mandates, focusing on a political transition favouring stability and the maintenance of the regime’s structures, as well as the war on terror. The major difference was Trump’s focus on opposition to Iran and seeing its influence diminished in Syria.

Gulf monarchies, led by Saudi Arabia and Qatar on one side, and Turkey on the other, adopted a more hostile position toward the Assad regime at the end of the summer 2011 after seeking a form of understanding with Damascus and some superficial reforms. Saudi Arabia, Qatar, and private networks from the Gulf monarchies funded and backed military and political groups, particularly Islamic fundamentalist and some jihadist movements, as a means of promoting forces on the ground that served their interests.

Riyadh’s main objective was to weaken Iran, seen as its main enemy in the region. Overthrowing the Assad regime, the main ally of Tehran in the region, was in Riyadh’s interest to strengthen a Sunni axis led by Saudi Arabia against Iran. On its side, Qatar saw the uprising as an opportunity to increase its own regional influence, notably through the MB and other Islamic fundamentalist actors. The Gulf monarchies feared the establishment of a form of democracy in Syria, which would threaten their own interests if democratic ideas and activities expanded in the MENA region. From this perspective, they preferred a sectarian war and encouraged a sectarian narrative through their media and funding.

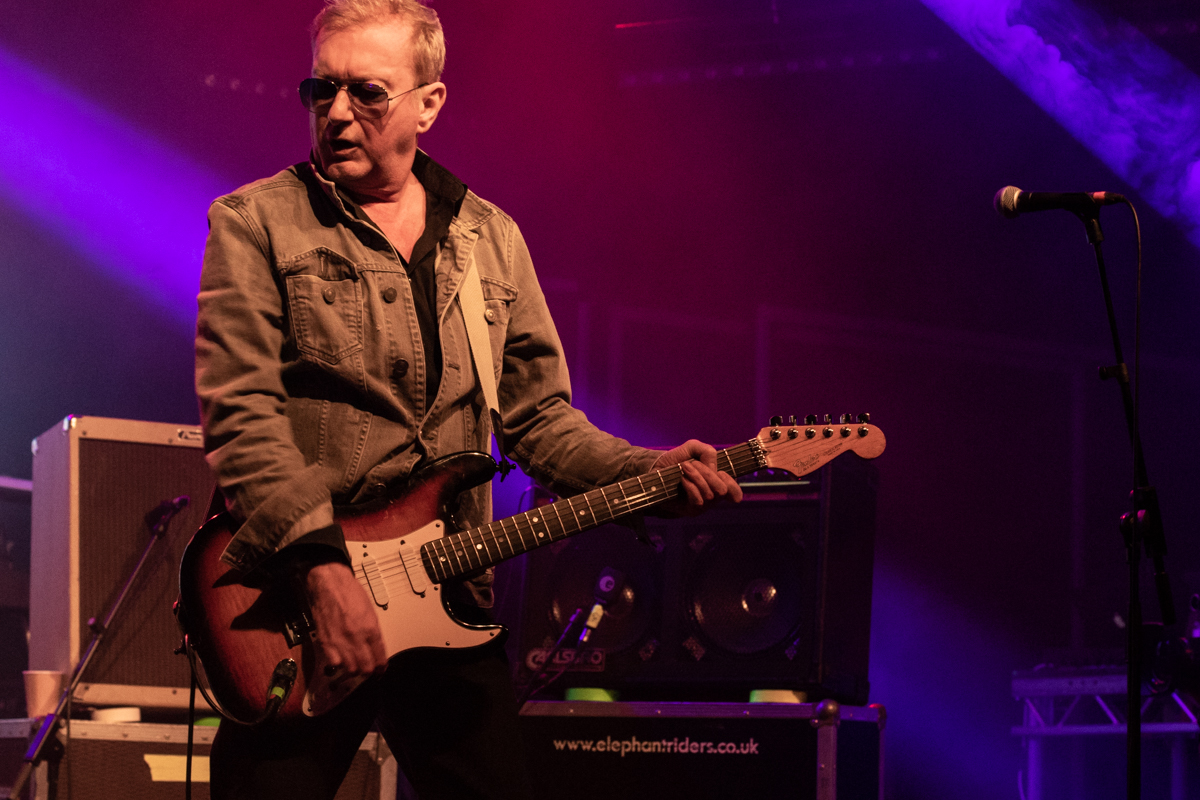

Similarly, Turkey initially supported the overthrow of Assad’s regime after failing to convince Damascus in the first months of the conflict to accept the integration of opposition forces close to Ankara in a unity government and superficial reforms. This objective was progressively abandoned, however, and the Turkish priority increasingly became the defeat of the Kurdish PYD and the cleansing of its forces at the borders. Free Syrian Army (FSA) groups and Islamic fundamentalist groups under Turkish influence were used as proxies in Ankara’s war against the Kurds. The policies of Gulf monarchies and Turkey promoted jihadist forces while dividing the FSA units through selective sponsoring. This situation amplified the sectarian effects of Iranian and Hezbollah interventions. This contributed to the Islamization of the armed opposition and the deepening of sectarian and Kurdish-Arab tensions. Demonstration, London, 28 December 2019 (photo: Steve Eason)

Many left-wing figures and groups, often from Stalinist, third worldist and campist frameworks, have analyzed the Syrian revolutionary process using a “top-down” approach or a war of blocs of countries, in which people need to choose a side. They characterize the popular Syrian uprising in Manichean terms as an opposition between two camps: the Western states, the Gulf monarchies, and Turkey (the “aggressors”) on one side, and Iran, Russia, and Hezbollah (the “resistance”) on the other. In doing so, they ignored the popular political and socio-economic dynamics at the grassroots . Moreover, they often focus disproportionately on the dangers of ISIS and other salafists and jihadist organizations while ignoring the role the Assad regime played in their rise. These discrepancies must be addressed within leftist circles and movements.

ISIS’s expansion is a fundamental element of the counter-revolution in the Middle East that emerged as the result of authoritarian regimes crushing popular movements linked to the 2011 Arab Spring. The interventions of regional and international states have contributed to ISIS’s development as well. Finally, neoliberal policies that have impoverished the popular class, together with the repression of democratic and trade union forces, have been key in helping ISIS and Islamic fundamentalist forces grow.

Only by ridding the region of the conditions that allowed them to develop can we resolve the crisis. Empowering those on the ground who are fighting to overthrow authoritarian regime and face reactionary groups is part and parcel of this approach.

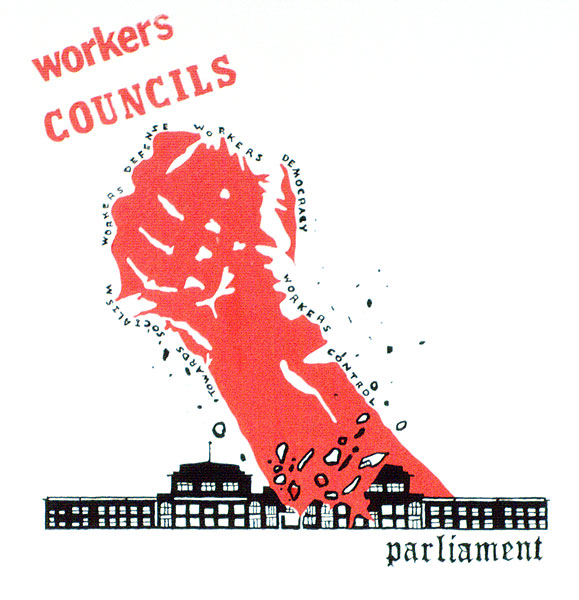

The initial popular resistance and self organization from below has also been the most neglected aspect of the Syrian uprising. Since the revolution began, some sections of the left and anti-war movements, especially in the UK and the United States, have refused to act in solidarity with the Syrian uprising under the pretext that “the main enemy is at home.” In other words, it is more important to defeat the imperialists and bourgeoisie in our own societies, even if that means implicitly supporting the Assad regime or Russian state.

These sections of the left frequently cite communist thinker Karl Liebknecht He is famous for his 1915 declaration that “the enemy is at home,” a statement made in condemnation of imperialist aggression against Russia led by his native Austria–Germany. In quoting him, many have decontextualized his views. From his perspective, fighting against the enemy at home did not mean ignoring foreign regimes repressing their own people or failing to show solidarity with the oppressed. Indeed, Liebknecht believed we must oppose our own ruling class’s push for war by “cooperating with the proletariat of other countries whose struggle is against their own imperialists.”

As leftists, our support must go to the revolutionary people struggling for freedom and emancipation. As Liebknecht said: “Ally yourselves to the international class struggle against the conspiracies of secret diplomacy, against imperialism, against war, for peace within the socialist spirit.” We can exclude none of these elements from our struggle to build a progressive leftist platform on Syria and everywhere else.

In the face of geopolitical tensions instrumentalized by the imperialist power of the US and regional powers such as Iran, the struggling popular classes should remain the lodestar of progressives and internationalists around the world

SR – What has been the relationship of the Kurds in Northern Syria with the Assad regime?

JD – Historically speaking, the Assad regime continued the discriminatory policies of previous Syrian governments toward the Kurds and maintained an institutionalized racist system against Kurdish populations in Syria. Between 1972 -1977, a policy of colonization was implemented in predominantly Kurdish regions of Syria as part of the Arab Belt plan. Around 25,000 “Arab” peasants, whose lands were flooded by the construction of the Tabqa Dam, were sent to the High Jazirah, where the Syrian regime established “modern villages” adjacent to Kurdish villages.

Meanwhile, the regime developed a policy of co-opting certain segments of Kurdish society — especially with the mounting opposition in the country at the end of the 1970s and the beginning of the 1980s, and to serve foreign policy objectives. Some Kurdish elites participated in the regime’s system, such as Kurdish leaders from the religious brotherhoods like Muhammad Sa’id Ramadan al-Buti and official sheikhs such as Ahmad Kuftaro, mufti of the republic between 1964 and 2004. Several Kurds held positions of local authority, while others reached high-ranking ones, such as Prime Minister Mahmud Ayyubi (1972–76), or Hikmat Shikaki, chief of military intelligence (1970– 74) and chief of staff (1974–98). However, this was on the condition that they not demonstrate any particular Kurdish ethnic consciousness in their rhetoric or political strategy. Some Kurds were also absorbed at the end of the 1970s and into the 1980s into elite divisions of the army or linked to specific military groups serving the regime. Another form of co-optation was the complicity of local security services with certain families of active Kurdish smugglers in the Jazirah on the Syria/Turkey and Syria/Iraq frontiers.

This policy of co-optation included some Kurdish political parties as well. The Assad regime established a sort of alliance with the PKK, and the Kurdish PKK leader Abdullah Öcalan became an official guest of the regime at the beginning of the 1980s as Syrian and Turkish tensions flared up. The PKK was authorized to recruit members and fighters, reaching between 5,000 and 10,000 persons in the 1990s and launching military operations from Syria against the Turkish army. The PKK had offices in Damascus and several northern cities. PKK militants took de facto control over small portions of Syrian territory, particularly in Afrin. Other Kurdish political parties also collaborated with the Syrian regime. Among these were the Patriotic Union of Kurdistan (PUK)led by Jalal Talabani, who had been in Syria since 1972, and later in 1979, the Kurdish Democratic Party (KDP), affiliated with the Kurdish leader Masoud Barzani.

The condition sine qua non of support from the Syrian regime was the abstention of the Kurdish movements of Iraq and Turkey from any attempt at mobilizing Syrian Kurds against Assad. Damascus was able to instrumentalize these Kurdish groups by using them as a foreign policy tool to achieve some regional ambitions and, at the national level, by diverting the Kurdish issue away from Syria and toward Iraq and Turkey.

Relations between the Kurdish political parties and the Syrian regime increasingly worsened through the late 1990s and into the early 2000s. An improvement in Turkish/Syrian relations prompted Syrian security forces to launch several waves of repression against the remaining PKK elements in Syria. Following the exile of Öcalan in 1998 and the imprisonment of many PKK members, the party’s activists tried to establish new parties, with the double objective of evading state repression and providing social support for its thousands of members and sympathizers. The PYD was created in 2003 as a successor to the PKK in Syria, part of the party’s regional strategy to establish local branches in neighbouring countries. Relations were similarly weakening with KDP and PUK from 2000 as Damascus was trying to normalize relations with Baghdad, which meant an end to its interference in Iraqi Kurdish affairs.

In 2004, the Kurdish uprising began in the town of Qamishli and spread through the predominantly Kurdish-inhabited regions of the country — Jazirah, Afrin, but also in Aleppo and Damascus, where demonstrations were severely repressed by the security forces. The regime appealed for the collaboration of some Arab tribes of the northeast that had historical ties to the regime. Around 2,000 protesters were arrested and 36 killed, while others were forced to leave the country. The Kurdish Intifada, as well as developments in Iraqi Kurdistan that saw increased autonomy and the raising of Kurdish flags and symbols, boosted Syrian Kurdish people’s morale and confidence in mobilizing for their rights and strengthened the nationalist consciousness of the youth and their will for change.

The Kurdish Youth Movement in Syria (known by its Kurdish acronym, TCK) was clandestinely established in March 2005, the year after the repression of the Kurdish uprising, and became the largest of the political youth groups after 2004. It would go on to be one of the key actors in the 2011 protests in Kurdish-majority areas.

Kurds continued to assert themselves by organizing events celebrating their ethnic identity and protesting against anti-Kurdish policies of the regime. Kurdish students of various political groups were also very active throughout the years on university campuses, particularly in Damascus and Aleppo.

Today, Bashar al-Assad and other officials have accused the PYD of being a “US stooge” and “tool” and have said they will “crush it,” considering Raqqa (former Da’esh capital, now PYD-held) to be occupied territory. In Afrin, for instance, the Russians pushed the PYD to make a deal with the regime, saying “if you remove all your heavy weapons and give in to the regime, Turkey will not come in and invade this area.” The PYD refused, and the result was the Turkish occupation of Afrin in 2018.

Even if there are now negotiations, the regime has refused any kind of conditions put by the PYD for federalism or decentralization. It’s wrong to say therefore has claimed that they’re allies, even if at some points there have been understandings between them.

SR – For a while Rojava was a source of hope with its local self-organisation and the positive role played by women. After Turkey’s invasion of the area, where is this movement now?

JD – Faced with regional and international pressures on the one hand, more especially of Turkey, and by the regime’s increasing willingness to reconquer all of Syria on the other, PYD officials more and more sought a form of reconciliation with Damascus to maintain its institutions and preserve its organizational structure within the country. Having seen the situation change in favour of the regime, some PYD officials had already declared their readiness to dialogue with the regime by the end of 2017. However, as SDF officials themselves recognized, major challenges stand in the way of future talks — notably the continuous absence of recognition of Kurdish rights and a federal political system.

Despite continuing talks, regime officials did not accept any of the conditions of the PYD, while state officials and the media continue to attack the Kurdish Party. The PYD has been seeking Russian mediation for talks with Damascus in order to prevent any invasion of Turkish forces against the regions they controlled, without much success. Russia has declared on numerous occasions that the Syrian regime must take control of the country’s northern provinces, notably to regain control of Syria’s oil reserves.

As I have said on many occasions, just as the rise of the uprising in Syria had pushed the regime to seek occasional and temporal agreements with the PYD, this threat was increasingly disappearing as its position strengthened and it recovered new territories with the assistance of its allies. The regime, therefore, could once more turn its forces against Kurdish inhabited regions or increasingly undermine its autonomy, especially with international actors, Russia and the United States, progressively abandoning the Kurdish group as their objectives differed from the latter after periods of collaborations. Turkey’s latest invasion in October 2019 reduced even more the PYD’s control.

As we have seen, the destiny of the Kurdish people in Syria was inextricably linked to the causes and conditions of the Syrian uprising. Therefore, their future is in danger and facing multiple threats, similar to the rest of the protest movement.

SR – Paradoxically, as Assad is about to win, new movements for democracy and against corruption erupt around Syria in Lebanon, Iraq and even Iran. What are the dynamics of these movements and what hope do they give?

JD – In Lebanon and Iraq, popular protest movements have been radically challenging the sectarian and neoliberal system, explicitly denouncing all the political parties ruling both countries as responsible for the deterioration of socio-economic conditions, corruption and sectarian tensions. Sectarianism in these two countries is, in fact, one of the main instruments used by the ruling parties to strengthen control over the working classes. Sectarianism must be understood as a tool of the Lebanese and Iraqi political elites to intervene ideologically in the class struggle, strengthen their control over the popular classes and keep them in a position of subordination in relation to their sectarian leaders. In the past, the ruling elites have succeeded in stopping or crushing protest movements not only by repression but by playing on sectarian and ethnic divisions. While large segments of the population sank into poverty, the dominant sectarian parties and various groups of the economic elite took advantage of the privatization processes, neoliberal policies, and the control of public prosecutors to develop powerful networks of patronage, patronage and corruption. Sectarianism must be seen as a constitutive and active element of current forms of state and class power in Lebanon and Iraq.

The demonstrators in Iraq also protested against Iran’s role in the country, chanting “Iran, Iran, outside, outside”. Tehran has had massive political and economic influence in Iraq since the US occupation in 2003, through its support for Islamic Shia fundamentalist movements and its armed militias.

In Iran, new mass demonstrations have taken place since the Iranian government acknowledged and initially denied responsibility for the crash of a Ukrainian plane over Tehran. Demonstrators in Tehran and many cities across the country expressed solidarity with the grieving families of the passengers and crew, and also launched hostile slogans against the leaders of the Islamic Republic of Iran and the Revolutionary Guard Corps (Pasdaran), including Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei, to the cries of “Death to the Dictator”.

Faced with the demonstrations against the regime, Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei, responded with a strong speech against the United States and European states, and against the popular protest, while praising the role of the Iranian Revolutionary Guards and General Soleimani in maintaining security in the region and the country.

In Iraq, Iran and its allies in the country are still trying to hijack the popular protest movement by limiting their demand to the departure of US troops, without any change in the Iraqi confessional and neo-liberal political system. In particular, the Shia Islamic fundamentalist leader Moqtada Sadr has called for a massive demonstration to denounce the US presence in Iraq.

In Lebanon, the popular revolt against the confessional and neo-liberal ruling class has entered its fourth month of struggle, with a clear tendency towards radicalization, as evidenced by the almost daily attacks against the headquarters of the Bank of Lebanon and other private banks, and the increasingly violent altercations with the forces of law and order.

I believe some lessons can learned from the experiences of Sudan and Tunisia, which are both in a less bad situation in comparison with other countries that witnessed popular uprising in the region. The main characteristic of the popular protest movement in Sudan and in Tunisia is the presence of democratic and progressive political and social actors with capacities of mobilisations and organisation, and more especially rooted in two pillars which until today play a central role in these two countries:

– A mass organized labour movement. The Sudanese Professional Associations, and UGTT trade union in Tunisia.

– Mass organized women’s and feminist movements. Women have played an essential role in the protest in Sudan and Tunisia. They also play a key role in workers’ organizations, including the Sudanese Professionals Association and the UGTT.

In the face of geopolitical tensions instrumentalized by the imperialist power of the US and regional powers such as Iran, the struggling popular classes remain the lodestar of progressives and internationalists around the world.

Reposted from No Borders News.

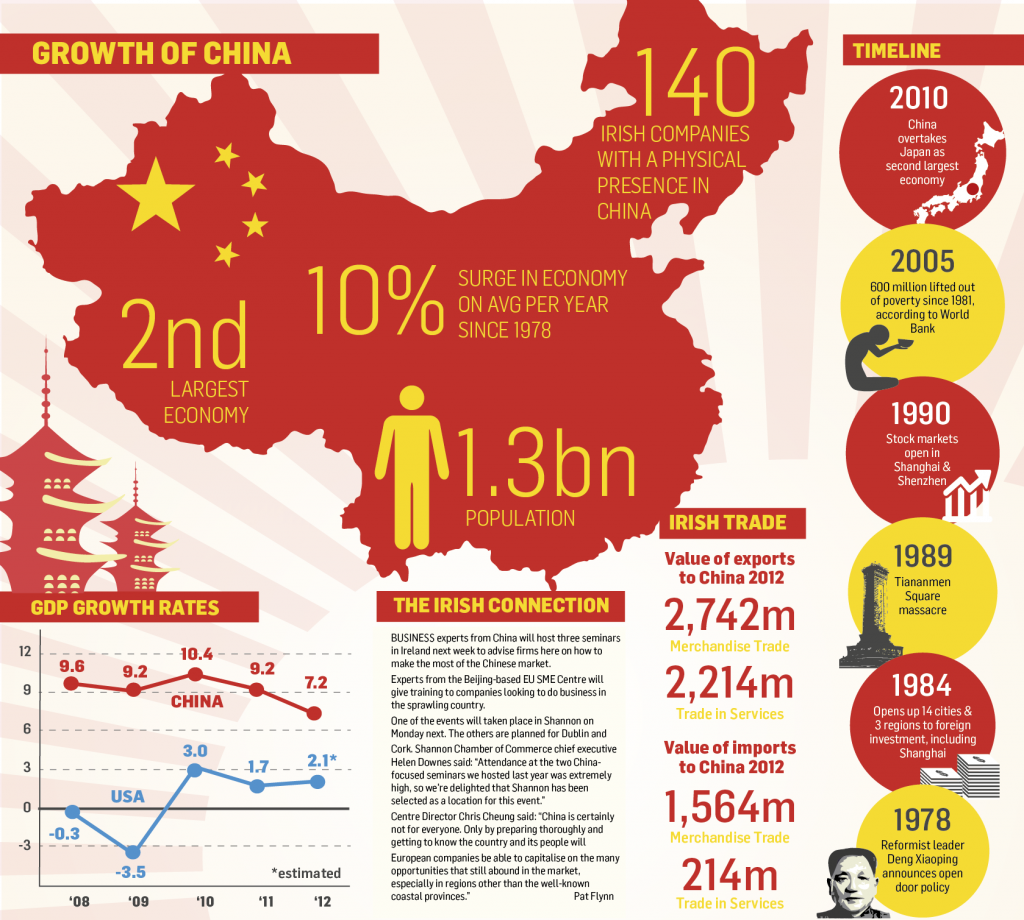

‘[T]here is a growing consensus,’ two Obama-era officials wrote recently in Foreign Affairs, ‘that the era of engagement with China has come to an unceremonious close.’ American intelligence chiefs now talk of the ‘existential threat’ that China poses to the US, while Secretary of State Mike Pompeo has been touring the globe lecturing nations on the risks of doing business with Beijing. There are, of course, the usual Trumpian contradictions. With his trade war arriving at an inconclusive phase-1 armistice, Donald Trump proclaimed in his State of the Union address that ‘we have the best relationship we’ve ever had with China.’ But the signs of brewing conflict across the Pacific are becoming more evident by the day.

‘[T]here is a growing consensus,’ two Obama-era officials wrote recently in Foreign Affairs, ‘that the era of engagement with China has come to an unceremonious close.’ American intelligence chiefs now talk of the ‘existential threat’ that China poses to the US, while Secretary of State Mike Pompeo has been touring the globe lecturing nations on the risks of doing business with Beijing. There are, of course, the usual Trumpian contradictions. With his trade war arriving at an inconclusive phase-1 armistice, Donald Trump proclaimed in his State of the Union address that ‘we have the best relationship we’ve ever had with China.’ But the signs of brewing conflict across the Pacific are becoming more evident by the day.

The western mainstream media tends to depict the situation of HK merely in a one dimensional manner, presenting Hong Kong a victim of Beijing’s tyranny while the US and the UK as supporters of Hong Kong’s autonomy and democracy. On the other hand, Beijing claims that it remains committed to Hong Kong’s autonomy and democracy but the latter is now under threat from “foreign intervention”. The two sides mirror each other in terms of their argument. The real picture is actually much more complicated.

The western mainstream media tends to depict the situation of HK merely in a one dimensional manner, presenting Hong Kong a victim of Beijing’s tyranny while the US and the UK as supporters of Hong Kong’s autonomy and democracy. On the other hand, Beijing claims that it remains committed to Hong Kong’s autonomy and democracy but the latter is now under threat from “foreign intervention”. The two sides mirror each other in terms of their argument. The real picture is actually much more complicated.

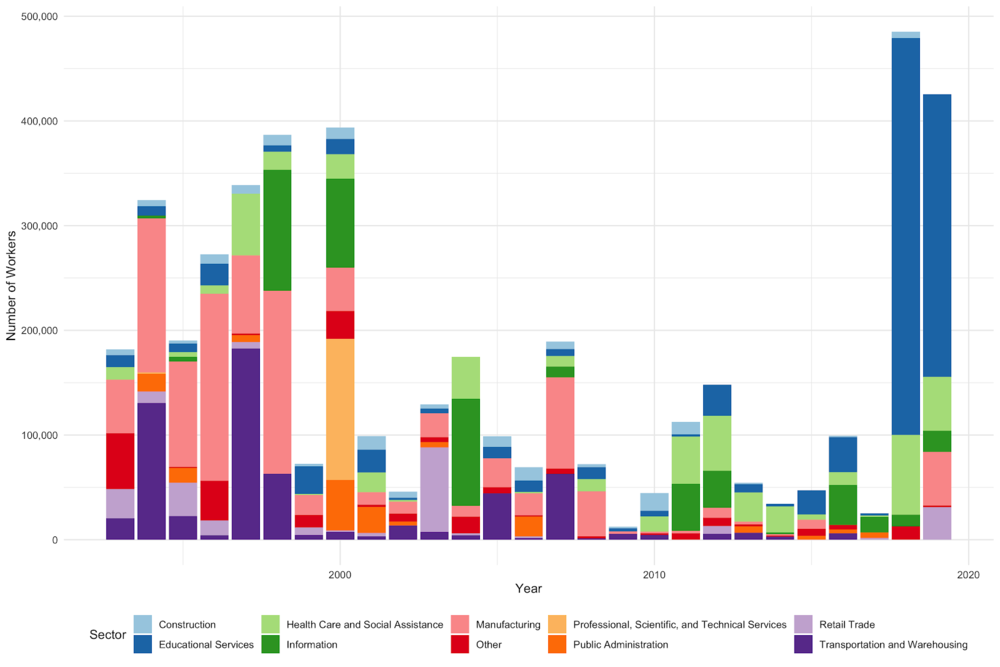

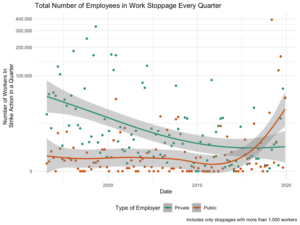

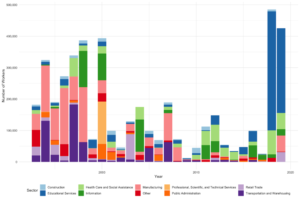

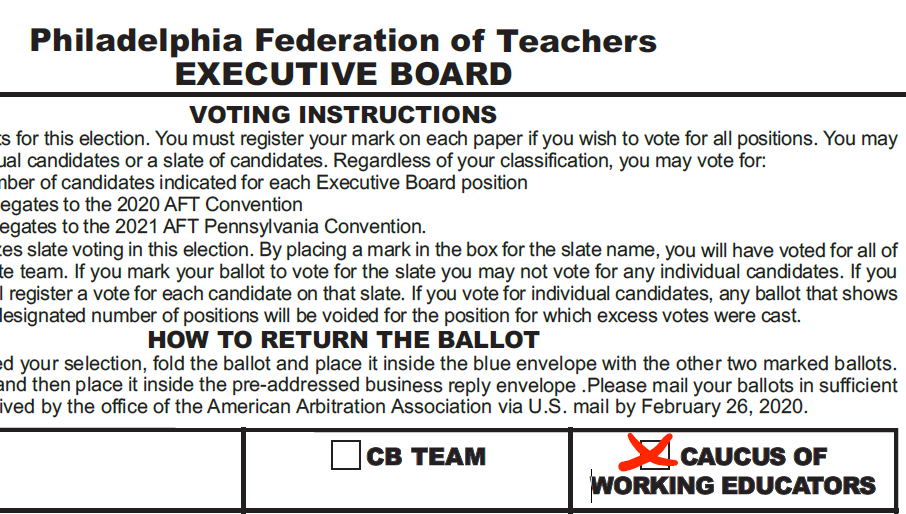

The 2012 Chicago teachers’ strike and the 2016 Verizon strike—the largest public sector and the largest private sector strikes in years, respectively—were warning shots.

The 2012 Chicago teachers’ strike and the 2016 Verizon strike—the largest public sector and the largest private sector strikes in years, respectively—were warning shots.

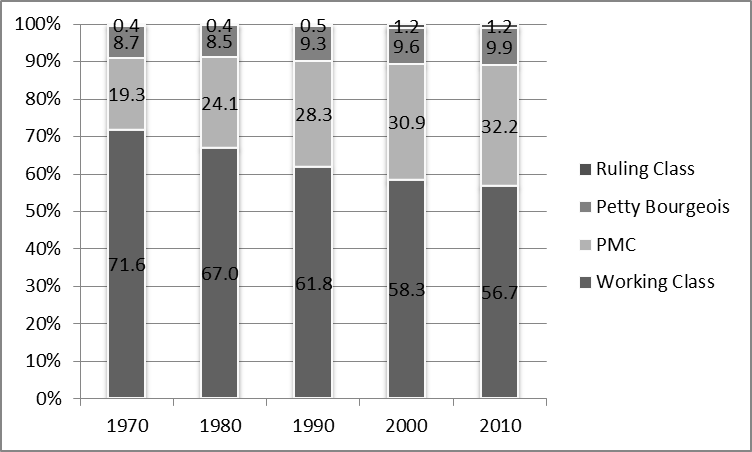

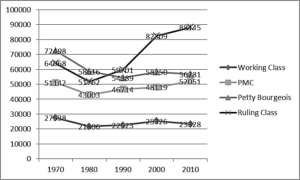

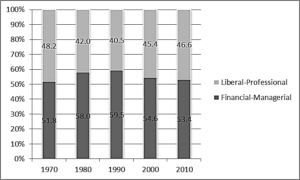

The annual

The annual

Joshua Kurlantzick, State Capitalism: How the Return of Statism Transformed the World. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2016.

Joshua Kurlantzick, State Capitalism: How the Return of Statism Transformed the World. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2016.

As Bashar al-Assad brutally crushes the last areas not under his control, Joseph Daher, Syrian socialist activist, gave this wide-ranging interview to the UK-based journal Socialist Resistance.

As Bashar al-Assad brutally crushes the last areas not under his control, Joseph Daher, Syrian socialist activist, gave this wide-ranging interview to the UK-based journal Socialist Resistance.

Dear Friends,

Dear Friends,

There have been many articles attempting to explain the crushing defeat of the Labour Party in the UK election of 12 December 2019. Some of them are very insightful, and list reasons that undoubtedly played a part in that defeat. However, I have not come across any which highlight two factors that are important, namely insufficient internationalism and a failure to uphold democracy strongly enough. Let me explain – but first, a brief summary of other viewpoints.

There have been many articles attempting to explain the crushing defeat of the Labour Party in the UK election of 12 December 2019. Some of them are very insightful, and list reasons that undoubtedly played a part in that defeat. However, I have not come across any which highlight two factors that are important, namely insufficient internationalism and a failure to uphold democracy strongly enough. Let me explain – but first, a brief summary of other viewpoints.

I. The ecological crisis is already the most important social and political question of the 21st century, and will become even more so in the coming months and years. The future of the planet, and thus of humanity, will be determined in the coming decades. Calculations by certain scientists as to scenarios for the year 2100 aren’t very useful for two reasons: a) scientific: considering all the retroactive effects impossible to calculate, it is very risky to make projections over a century. B) political: at the end of the century, all of us, our children and grandchildren will be gone, so who cares?

I. The ecological crisis is already the most important social and political question of the 21st century, and will become even more so in the coming months and years. The future of the planet, and thus of humanity, will be determined in the coming decades. Calculations by certain scientists as to scenarios for the year 2100 aren’t very useful for two reasons: a) scientific: considering all the retroactive effects impossible to calculate, it is very risky to make projections over a century. B) political: at the end of the century, all of us, our children and grandchildren will be gone, so who cares?

Andy Sernatinger’s New Politics article

Andy Sernatinger’s New Politics article

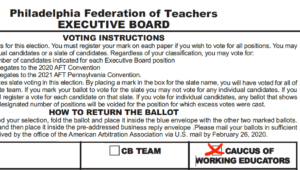

For people of a certain age — Generation X, they used to call us — it’s something of a cliche that if you loved punk rock and had leftist leanings you’d find your way to hearing a Gang of Four album. That album was probably their debut LP Entertainment! — sorry, I meant the “

For people of a certain age — Generation X, they used to call us — it’s something of a cliche that if you loved punk rock and had leftist leanings you’d find your way to hearing a Gang of Four album. That album was probably their debut LP Entertainment! — sorry, I meant the “

The Global Ecosocialist Network (GEN) is being launched at a moment of extreme danger for humanity. The intensity of the crisis and the scale of the danger is hard to grasp or express adequately because, unless you are in one of the parts of the world currently experiencing extreme weather, it cannot yet literally be seen. And even where the danger is actually being experienced there are very powerful forces at work to obscure its real causes.

The Global Ecosocialist Network (GEN) is being launched at a moment of extreme danger for humanity. The intensity of the crisis and the scale of the danger is hard to grasp or express adequately because, unless you are in one of the parts of the world currently experiencing extreme weather, it cannot yet literally be seen. And even where the danger is actually being experienced there are very powerful forces at work to obscure its real causes.

While I found

While I found

More than 100,000 metal workers in Turkey are getting prepared to launch a strike, a sizable section on the 5th of February, 2020. This comes after

More than 100,000 metal workers in Turkey are getting prepared to launch a strike, a sizable section on the 5th of February, 2020. This comes after

In March of 2019, the Democratic Socialists of America (DSA) endorsed Bernie Sanders’ bid for President of the United States. DSA members voted on an advisory referendum that simply asked if the Democratic Socialists of America should endorse Bernie Sanders for President. 76% of the 13,324 members who participated (24% of the membership) voted YES. NO votes cited the particulars of the endorsement: the referendum only had members vote on whether to endorse, not whether to adopt the plan for an

In March of 2019, the Democratic Socialists of America (DSA) endorsed Bernie Sanders’ bid for President of the United States. DSA members voted on an advisory referendum that simply asked if the Democratic Socialists of America should endorse Bernie Sanders for President. 76% of the 13,324 members who participated (24% of the membership) voted YES. NO votes cited the particulars of the endorsement: the referendum only had members vote on whether to endorse, not whether to adopt the plan for an

The US military’s assassination of Qasem Soleimani, one of the top military commanders of the Islamic Republic of Iran’s expansionist regional policies and its proxy wars in the Middle East, can lead to retaliation by the Islamist regime. Such retaliation, the threat of further US retaliation and a chain reaction could further destabilize the region and endanger the lives of thousands of Iraqis, Iranians and other ordinary people in the Middle East. IASWI strongly condemns the Trump administration’s military adventurism in Iraq, which is a continuation of the catastrophic US invasion of this country. Furthermore, we denounce IRI’s bloody interventions in Iraq and its participation in repression of the Iraqi protesters. We support the demands of many Iranians and Iraqis, particularly during the recent uprisings, calling on both American and Iranian military and paramilitary forces to leave Iraq immediately and refrain from further endangering the lives of Iraqis and other people in the region.

The US military’s assassination of Qasem Soleimani, one of the top military commanders of the Islamic Republic of Iran’s expansionist regional policies and its proxy wars in the Middle East, can lead to retaliation by the Islamist regime. Such retaliation, the threat of further US retaliation and a chain reaction could further destabilize the region and endanger the lives of thousands of Iraqis, Iranians and other ordinary people in the Middle East. IASWI strongly condemns the Trump administration’s military adventurism in Iraq, which is a continuation of the catastrophic US invasion of this country. Furthermore, we denounce IRI’s bloody interventions in Iraq and its participation in repression of the Iraqi protesters. We support the demands of many Iranians and Iraqis, particularly during the recent uprisings, calling on both American and Iranian military and paramilitary forces to leave Iraq immediately and refrain from further endangering the lives of Iraqis and other people in the region.

In

In

Brazil dominates Latin America’s economy. And although the coup in Bolivia, uprisings in Chile, Ecuador, and Columbia, Trump’s threats against Iran, Australian megafires, mass strikes in India and France, anti-government protests in Lebanon, and the British elections have pushed Brazil off the front of the international pages, what happens in Brazil will go a long way to determining the social and politic balance of power in Latin America in the coming period. In just one year, far-right Brazilian president

Brazil dominates Latin America’s economy. And although the coup in Bolivia, uprisings in Chile, Ecuador, and Columbia, Trump’s threats against Iran, Australian megafires, mass strikes in India and France, anti-government protests in Lebanon, and the British elections have pushed Brazil off the front of the international pages, what happens in Brazil will go a long way to determining the social and politic balance of power in Latin America in the coming period. In just one year, far-right Brazilian president