I have written at some length about my experience as a member of Workers World Party, which I left due to the organization’s flawed political practice. What I’ve said less about is my psychological and ideological state during this time. If “Where’s the Winter Palace?” was a critique of the concrete practices of modern Marxism-Leninism, then this piece will be an account of the political, ideological, and psychological mindset I adopted within this milieu. I lost sight of my original thirst for truth and justice that radicalized me in the first place, instead internalizing a dogmatic and sectarian, even cultic, closed worldview.

I have written at some length about my experience as a member of Workers World Party, which I left due to the organization’s flawed political practice. What I’ve said less about is my psychological and ideological state during this time. If “Where’s the Winter Palace?” was a critique of the concrete practices of modern Marxism-Leninism, then this piece will be an account of the political, ideological, and psychological mindset I adopted within this milieu. I lost sight of my original thirst for truth and justice that radicalized me in the first place, instead internalizing a dogmatic and sectarian, even cultic, closed worldview.

In my original resignation letter from the party, I made what I still feel are insightful critiques of WWP’s practices, but within a broader argument that WWP’s problems stemmed from it not being sufficiently Leninist, from failing to properly practice “democratic centralism.” The only tools I had at the time were to critique WWP by measuring it up against its own proclaimed orthodoxy.1

It is also worth noting that my time spent in the Stalinist milieu was consumed mostly by “leftbook,” which I participated in for several years, which dwarfs my short five-month stint in WWP (although I regularly worked with WWP for the majority of those three years). Many who are reading this blogpost are familiar with the toxic group dynamics in leftist cliques on Facebook and Twitter. I don’t think I have anything interesting to say about these cultic parasocial groupings, and I believe it’s readily apparent that these group dynamics function independently of ideology. Similar trends of bullying, browbeating, and infighting have been reported across ideological tendencies.

However, I also believe it can be said that Stalinism’s unique characteristics of authoritarianism and apologism make it a particularly potent ideology for online sects. I spent hundreds or even thousands of hours in a state of anxiety, arguing online about the USSR, North Korea, etc. I believed I was fighting the good fight by cyberbullying. I cannot fathom how much time and energy I wasted on this fruitless endeavor; I often wonder how many times I caused an interlocutor to have an anxiety attack. During my time as an internet Stalinist, I became withdrawn from essentially all non-political activity. I alienated my friends through my abrasive argumentation and denunciations; I consciously built my social surrounding into an echochamber. I began to see everyone in my life as either potential recruits or sworn enemies.

When I first became disillusioned with “leftbook” and its unhealthy dynamics, which happened far in advance of my break from Stalinism, I at least believed that I may have educated some people, despite the negative aspects. Now I don’t even believe in the gospel I was spreading.

It was only later that I began to question the actual theoretical and historical suppositions of “Marxism-Leninism,” and in the process start to reconstruct my politics. Upon deconstructing the mythologies of modern “Marxism-Leninism” and its hodgepodge of ideologies and movements (some of which are in direct contradiction), I was confronted with that bugbear of the twentieth-century, the thorn in the side of every modern-day Marxist: Stalinism.

Confronting Stalinism was not an easy mountain to climb, as I had for years internalized the dogma that “Stalinism isn’t real, it’s just Marxism-Leninism.” Mass executions, routine party purges, ethnic deportations, brutal collectivization campaigns: if Stalinism is not real, what was all this? Indeed, perhaps the reverse is slightly closer to the truth: Marxism-Leninism isn’t real, it’s just Stalinism. (Of course, Khrushchev’s partial de-Stalinization and Maoism’s internal critique of Stalinism are worth noting.) I began to accept that Stalinism was something real, something to come to terms with, through reading various dissident and ex-Stalinist Communists, including Italo Calvino, Victor Serge, Isaac Deutscher, Russell Jacoby, Leon Trotsky, and Herbert Marcuse. Alongside them I read revisionist Soviet historians, chiefly Moshe Lewin and Sheila Fitzpatrick.

While the most heinous crimes of Stalinism are firmly buried in the twentieth-century, its echoes are still heard today, else I never would have taken up such an abhorrent ideology. In the post-2008 world of rising student debt, looming climate catastrophe, endless war in the Middle East, and the rise of a new populist Right, young people are increasingly dissatisfied with a world in which we feel that we have no future. Some have turned to democratic socialism, nihilism, social media humor, or some combination of the three. A small set have turned backwards towards the late Eastern Bloc, mourning the collapse of a possible socialist future. Indeed, “the tradition of all dead generations weighs like a nightmare on the brains of the living.”2

The most devoted adherents of modern Marxism-Leninism have turned additionally towards modern China, the last remaining bastion of Communist officialdom with a sizable role in global politics. Lacking a coherent alternative, these young “Dengists” see brutal Chinese capitalism as precisely its opposite, a thriving (if complex) socialist society. I am only grateful that I broke from Stalinism when I did, else no doubt at this very moment I would be ardently defending the atrocities in Xinjiang committed against Uyghur Muslims in the name of “anti-terrorism.”3

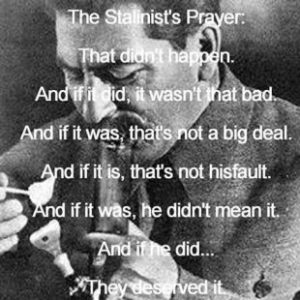

The incredible thing about Stalinist ideology is that I was amongst very sharp, critical thinkers who could build sophisticated analyses of capitalism, imperialism, etc. But when it came to any critical inquiry into state socialism, it was as if our brains switched off. Many a time I ardently defended for example the deportation of the entire Crimean Tatar people during WWII as necessary, if unfortunate. I argued that Trotsky, Bukharin, Zinoviev, all deserved to die for their alleged transgressions. If I’d known about the hundreds of KPD members that Stalin handed over to the Gestapo,4 I would have figured out a way to defend that too. I actually believed that by arguing as such, I was on the side of freedom and justice. The novelist and former PCI member Italo Calvino aptly described this mindset required to defend Stalin’s crimes:

We Italian Communists were schizophrenic. Yes, I really think that that is the correct term. One side of our minds was and wanted to be a witness to the truth, avenging the wrongs suffered by the weak and oppressed, and defending justice against every abuse. The other side justified those wrongs, the abuses, the tyrannies of the party, Stalin, all in the name of the Cause.5

We built simplistic narratives around a deceptive interpretation of certain scattered facts. Our arguments were built almost completely on official Soviet propaganda and the works of Grover Furr, a thoroughly discredited non-historian who takes confessions extracted via torture at face value. When we actually read reputable revisionist Soviet historians like Sheila Fitzpatrick or J. Arch Getty, it was only to extract isolated facts from their research, discarding their actual arguments and biting criticisms of Soviet bureaucracy. “Totalitarian narrative is flawed? Good enough for me, I knew Stalin was great,” so the logic went.

We argued that the Hungarian Revolution of 1956 was primarily fascist in character, without even bothering to cite any sources other than Soviet government statements. In one of our most impressive acts of mental gymnastics, we cited Stalin’s statement condemning antisemitism as evidence that antisemitism did not exist in the USSR, or at least was not sanctioned by the government. The doctor’s plot and the campaign against “rootless cosmopolitanism” were of course chalked up to Western propaganda.

We dismissed the Holodomor famine as Nazi propaganda, using the research of Tauger and Wheatcroft to essentially argue that the Soviet government had no complicity whatsoever in the famines. But even if the famines were not a Ukranian genocide (after all, they did hit the Kazakhs just as hard), it does not mean that the famine could be fully explained by bad weather, kulak subversion, and imperialist pressure. If we could so incisively argue that a hurricane devastating Houston, Texas could not be called a “natural disaster,” why were we so resistant to say the same thing of hunger on the Eurasian steppe in the early 1930s?

A lot of my writings from this time are innocuous enough, if a bit naive. But I want to turn specifically towards a few pieces which I believe most reveal the ugly flaws of my old views.

Towards the end of my time as a Stalinist, I started churning out pieces in defense of the basic orientation of the Communist Party of China. Again I am all too happy that I ceased this practice before getting the chance to write something about Xinjiang or Hong Kong. I wrote two naive articles in defense of the PRC’s environmental policy, “Disaster Relief: Capitalism and Socialism,” and “Socialism is the future: China leads the way on the environment.” More substantially, I wrote a sprawling blog post in defense of Deng Xiaoping and the “capitalist roaders,” against the Great Leap Forward and the Cultural Revolution. While I am still critical of Mao’s regime, especially the horrific consequences of the GLF, such a critique in no way vindicates the leaders and factions that ushered in the integration of China into global capitalism, with the simultaneous progress and suffering that entails.

I also wrote several articles on the war in Syria. While I remain critical of most of the militarized opposition forces, my writings on the topic amounted to apologism for the crimes of the Syrian government, mostly by way of omission. Anti-interventionism and a broad anti-imperialist outlook are vital for any sort of socialist movement in the United States, the principal global military power on the planet. Nonetheless, that is no excuse to downplay, deny, or justify the atrocities committed by the Assad regime. The logic of such apologism is nearly identical to defenses of Stalin.

My most regretful article is “Russophobia and the Logic of Imperialism.” In the piece, I draw on the scholarship of Domenico Losurdo contra Hannah Arendt and the “totalitarian” school of Soviet history. All that is fine enough, and I still side with the critique of the “double genocide” theory of WWII, but the article is deeply flawed. First, I make bold claims about the racialization of Russians and Slavs that were based on little to no research or historical evidence. I can only imagine I accepted this narrative through internalizing the ambient Great Russian chauvinism of Stalinist mythos.

Second, and this was the most crucial mistake, I equated any sort of critique of Stalinism (or, Christ, even the Russian Federation under Putin) with Orientalism. In my mind, any critique of Stalin was by necessity racist and anti-communist. Given that many of Stalin’s victims were oppressed minorities such as Chechens, Crimean Tatars, and Kazakhs, this claim hardly holds weight and carries a regretful irony. Of course, there are Russophobic critiques of the Soviet Union, but to lump all critiques under this umbrella is cynicism and bad-faith argumentation of the highest order. Ironically enough, I now quite enjoy the writings of Raya Dunayevskaya and Hillel Ticktin, both of whom I chastise in the piece.

Coming to terms with and eventually abandoning Stalinism was a long process involving numerous stages of research and self-reflection. It did not happen overnight. My old views grow more incomprehensible by the day, and while my politics are still evolving as always, I hope now I’m moving in the right direction, towards a more rigorous and consistent socialist outlook.

What do I mean by “Stalinism”?

What follows is my broad strokes understanding of Stalinism. It is not meant to be a comprehensive historical account of the Stalin period, nor is it much of a rigorous analysis. Rather, it is a gesture towards understanding some of the key features of Stalinism, which is primarily defined by, but not limited to, the Stalin era itself (~1928-1953). The phenomenon includes not just the actions of Stalin but also those of figures such as Beria and Yezhov, and more importantly the institutions and practices characteristic of the period. The ‘Further Reading’ section at the end of this piece enumerates the most important sources from which I derived my understanding of Stalinism.

Substitutionism

A major hallmark of Stalinism, which continues to this day, is the uncritical accepting of State propaganda, and more broadly siding with the State against the workers, if it’s a state deemed “good,” either due to its ostensible socialism or its ostensible anti-imperialism (or mere anti-Americanism). But the basic defense of the existence of a state (whether it be the socialists defending the USSR or liberals defending the United States) does not have to entail the defense of every action taken by said state, nor does it have to entail the defense of the state against internal rebellion. For Victor Serge, the elevation of Marxism to State ideology undermined its critical character:

All the same, I cannot help considering as a positive disaster the fact that a Marxist orthodoxy should, in a great country in the throes of social transformation, have taken over the apparatus of power. Whatever may be the scientific value of a doctrine, from the moment that it becomes governmental, interests of State will cease to allow it the possibility of impartial inquiry.6

Thus, the basis was laid for a “Marxist” justification of Stalinism’s state violence. This ‘statism’ is tied with a warped view of class. In Stalinist, as in much traditional Marxist thought, “the proletariat” is defined as a coherent political category with its own interests, cohesion, and even psyche. We can see how the heroic belief in the proletariat as a revolutionary subject devolved into authoritarianism. If the proletariat is the vanguard of humanity, of progress, and the Party is the vanguard of the proletariat, then the Party’s ruling clique can justify the most heinous crimes as being “objectively” in the interests of humanity.

This understanding of class often vacillates between basing itself on relations of production and on political outlook.7 Thus not only were the former bourgeoisie, expropriated kulaks, and their respective social circles politically suppressed, but so too were “objective agents” of the old ruling class, “counter-revolutionaries,” and “Trotskyites.” These dubious political categories were extended to eventually engulf the majority of the delegates to the 1934 Party Congress, 1,108 of whom were arrested and 848 shot during the Great Terror.8

The interests of the class are defined by the Party Line, and thus the Party substitutes itself for the class, “acting out its deepest desires.”9 Once the Bolshevik Party was in power, the interests of the proletariat were defined by the interests of the State, and thus “the cruelest and most repressive forms of the primitive accumulation of capital [were] carried out against the empirical proletariat, in the name of a metaphysical proletariat.”10 This subtle substitutionism was even explicitly argued by Stalin himself when he spoke about how the Moscow Trials should be written about:

…Stalin and the other leaders are not isolated individuals but the personification of all the victories of socialism in the USSR, the personification of collectivization, industrialization, and the blossoming of culture in the USSR, consequently, the personification of the efforts of workers, peasants, and the working intelligentsia for the defeat of capitalism and the triumph of socialism.11

In other words, to disagree with Stalin is to betray the Party, and hence socialism and the proletariat. Stalin’s words send shivers down my spine.

Productivism and Carceralism

The repressive and statist aspects of Stalinism were only one side of the coin: the other was primitive accumulation, in a nakedly brutal form. To be absolutely clear, Soviet industrialization was not uniquely violent. One only has to consider European wars of conquest, the genocide of Indigenous Americans, slavery, and the never-ending death toll of capitalist modernity. But neither was it uniquely peaceful and painless. The collectivization campaign, driving millions of peasants from the land, was proletarianization on an unprecedented scale and pace (only to be surpassed later by post-Mao China). Laws against absenteeism, internal passports, colonial relations with nomadic peoples (notably Kazakhs and Roma), and a general regime of labor discipline and modernization marked the political economy of Stalinism, its own mirror image of “the rosy dawn of the era of capitalist production.”12

Perhaps this is one of the most important lessons of Stalinism: that certain institutions and economic imperatives command their own logic, relatively autonomous from political ideology or “class” (itself a fraught and culturally/historically contingent category). In this sense, there’s no “class character” to labor camps, industrialization, mass execution, secret police, and the like. No matter who is in charge, these institutions will likely operate on similar lines. I believe this is especially true of the economic necessities of industrialization, which by necessity squeeze the peasantry and discipline a laboring class, whether or not this process of primitive accumulation is led by the State or by market forces. This, to me, is a more compelling critique of Stalinism than the anti-revisionist accounts of socialist collapse: it is not the danger of a new or reconstituted bourgeoisie, but rather the institutions themselves and the dynamics they engender.

Stalinism may be appealing because it appears to be a radical break from the neoliberal consensus, but in fact its mechanisms of population control, mass incarceration, and labor discipline were endemic features in its contemporary counterparts, both liberal and fascist. For example, concentration camps, a hallmark of Stalinist political repression, were first pioneered by the British in India and South Africa. Similarly today, camps in Xinjiang and El Paso are both manifestations of the policing and disciplining paradigms of modern global capitalism. We don’t have to accept the now discredited totalitarian paradigm to recognize the authoritarian and violent nature of Stalinism’s core political and legal institutions. The Great Terror (which claimed the lives of at least 600,000 people) was in many ways a unique historical event, but its carceral backdrop was not unlike those of other nation-states of capitalist modernity.

The Question of Liberalism

On a broader point, I think the legacy of 20th century state socialism proves that Marxism in fact never really squared the circle in terms of its relationship with political liberalism and democracy. Some argue that Marxism is a negation of political liberalism; others its culmination. I think it’s a bit of both. But one thing is clear, the profound strides in positive and material rights (housing, food, education, healthcare, etc.) made under state socialism were unfortunately not paired with an equal increase (or in some cases, even maintenance) of democratic rights in the tradition of the French Revolution’s liberalism and the Declaration of the Rights of Man. It is too simplistic to denounce political liberalism as “bourgeois”, for it is readily apparent that workers themselves did not enjoy certain freedoms under Stalin. For example the right to an attorney and a fair trial was not awarded until Khrushchev’s de-Stalinization campaign.13

At stake here is the question of universal principle. Are we to organize to abolish the death penalty under capitalism only to reinstate it under a socialist regime?14 Stalinism answers this question by rejecting universal principles, making allowance for various mechanisms of violence as long as they serve the “class interests” of a mystified proletariat. However, I believe Marxists should hold onto at least some notion of universal principles. The ends do not necessarily justify the means: “Alright, I can see the broken eggs. Where’s this omelette of yours?”15 Not only do repressive measures such as torture and mass execution likely warp the psychology of their purveyors, but additionally, plenty of innocent workers, peasants, and revolutionaries got caught up in the dragnet of a carceral system ostensibly functioning on their behalf.

Czechoslovak dissident Jiri Pelikan wrote in an open letter to Angela Davis, urging her to support Czechoslovak political prisoners:

… [my Western friends] reply that of course it’s a disagreeable situation but that one mustn’t say so too openly so as not to “play into the hands of socialism’s enemies,” and that one must start from “a class position.” But what “class” can benefit if people are arrested without trial, if trade unions are enslaved, if all free discussion is suppressed, if socialist countries accuse each other of imperialism, betrayal, revisionism, and invade each other by turn?16

Tragically, Angela Davis’s response was not sympathetic. According to the London Times, “a close friend of Angela Davis, who claimed that she spoke on her behalf, said that Angela Davis held the view that those who were jailed in Eastern Europe were trying to undermine their governments and that those who went into political exile were attacking their own countries and therefore undeserving of her support.”17 This sadly mirrors the logic used to vilify political dissidents in capitalist regimes. Even if one by-and-large supported the political systems of the Eastern Bloc, it’s difficult to imagine that support extending to such repressive measures.

On “Necessity”

If it is simplistic to dismiss democratic rights as bourgeois, is equally simplistic to apologize for Stalinism’s crimes and the limitations on democratic rights just because they were “historically necessary.” As Calvino said:

Stalinism relied on necessity, things could not happen any other way from the way they happened, even though the face of that history had nothing pleasant about it. Only when I managed to understand that even inside the most iron necessity there is a point where choices are possible, and Stalin’s choices had been largely disastrous, did any justification of Stalinism become unthinkable.18 (emphasis original)

When we investigate the specifics of the Stalin era, it becomes apparent that few if any of the worst excesses could be explained away as “necessities.” But the point of this essay is not to argue that Stalin’s crimes were indeed abhorrent and unnecessary. Only the most hardened apologists would deny as such; I used to be one of them, and one thing I believe is that they can only change their minds by their own accord. Lord knows no person, fact, or book could have changed my mind about Stalin when I was so dead set on defending his every action.

While there are many lessons to learn from 20th century state socialism, positive and negative, a critical appraisal of our past is only possible by shedding the apologist mindset of modern Stalinism. My hope is that a critical distance from past and present State doctrines will allow us to reinvigorate Marxism’s spirit of “ruthless critique” and a robust commitment to intellectual honesty.

Further Reading

- Italo Calvino, Hermit in Paris

- Isaac Deutscher, The Prophet

- Arch Getty and Oleg G. Naumov, The Road to Terror: Stalin and the Self-Destruction of the Bolsheviks

- Vivian Gornick, The Romance of American Communism

- Sheila Fitzpatrick, Cultural Revolution in Russia, 1928-1931

- Sheila Fitzpatrick, Everyday Stalinism: Ordinary Life in Extraordinary Times

- Sheila Fitzpatrick, Stalinism: New Directions

- Russell Jacoby, The Dialectic of Defeat: Contours of Western Marxism

- Russell Jacoby, “Stalin, Marxism-Leninism and the Left”

- Moshe Lewin, The Soviet Century

- Herbert Marcuse, A Critique of Soviet Marxism

- Raphael Samuel, The Lost World of British Communism

- Victor Serge, Memoirs of a Revolutionary

- Leon Trotsky, The Revolution Betrayed

- Slavoj Zizek, “Stalinism”

Notes

- Although WWP had Trotskyist origins, Marcyist ideology trends towards a certain Stalinist logic especially around international politics and “defending” anti-American regimes. My problem with Marcyism, initially, was precisely that it was not Stalinist enough. But none of what I discuss below is characteristic of Trotskyism as such.

- Marx, The Eighteenth Brumaire.

- See Adam Hunerven, “Spirit Breaking: Capitalism and Terror in Northwest China” in Chuang 2: Frontiers.

- ‘September 1939. Hitler and Stalin have just carved up Poland. At the border bridge of Brest-Litovsk, several hundred members of the KPD, refugees in the USSR subsequently arrested as “counter-revolutionaries”, are taken from Stalinist prisons and handed over to the Gestapo. Years later, one of them would explain the scars on her back — “GPU did it” — and her torn fingernails — “and that’s the Gestapo”. A fair account of the first half of this century.’ Gilles Dauvé, “When Insurrections Die,” Endnotes 1.

- Italo Calvino, “The Summer of ‘56” in Hermit in Paris 203.

- Victor Serge, Memoirs of a Revolutionary 441.

- The latter case was taken to its extreme with the Maoist concept of “two-line struggle” and the identification of individuals with classes based on their views.

- Moshe Lewin, The Soviet Century 105.

- Raphael Samuel, “The Lost World of British Communism, Part III” New Left Review 57.

- Robert Kurz, “The German war economy and state socialism.”

- Stalin to Kaganovich and Molotov.

- Karl Marx, Capital Volume I, “Chapter 31: The Genesis of the Industrial Capitalist.”

- Moshe Lewin, The Soviet Century.

- It is worth noting that the Paris Commune abolished the guillotine, that timeless symbol of Jacobin radicalism. See Crimethinc, “Against the Logic of the Guillotine.”

- Panait Istrati, quoted in Victor Serge, Memoirs of a Revolutionary 323.

- Jiri Pelikan, “An Open Letter to Angela Davis.”

- Ibid.

- Italo Calvino, “Was I a Stalinist Too?” in Hermit in Paris 195.

Originally posted at The Left Wind.

The criminal negligence of the Iranian regime and military — shooting down a passenger airliner that had just taken off from their own Tehran airport — should immediately remind us of the dozens, if not hundreds of occasions when United States forces have caused the same kind of civilian collateral carnage.

The criminal negligence of the Iranian regime and military — shooting down a passenger airliner that had just taken off from their own Tehran airport — should immediately remind us of the dozens, if not hundreds of occasions when United States forces have caused the same kind of civilian collateral carnage.

The nationwide general strike in France, now in its record seventh week, seems to be approaching its crisis point. Despite savage police repression, about a million people are in the streets protesting President Macron’s proposed neoliberal “reform” of France’s retirement system, established at the end of World War II and considered one of the best in the world. At bottom, what is at stake is a whole vision of what kind of society people want to live in – one based on cold market calculation or one based on human solidarity – and neither side shows any sign of willingness to compromise.

The nationwide general strike in France, now in its record seventh week, seems to be approaching its crisis point. Despite savage police repression, about a million people are in the streets protesting President Macron’s proposed neoliberal “reform” of France’s retirement system, established at the end of World War II and considered one of the best in the world. At bottom, what is at stake is a whole vision of what kind of society people want to live in – one based on cold market calculation or one based on human solidarity – and neither side shows any sign of willingness to compromise.

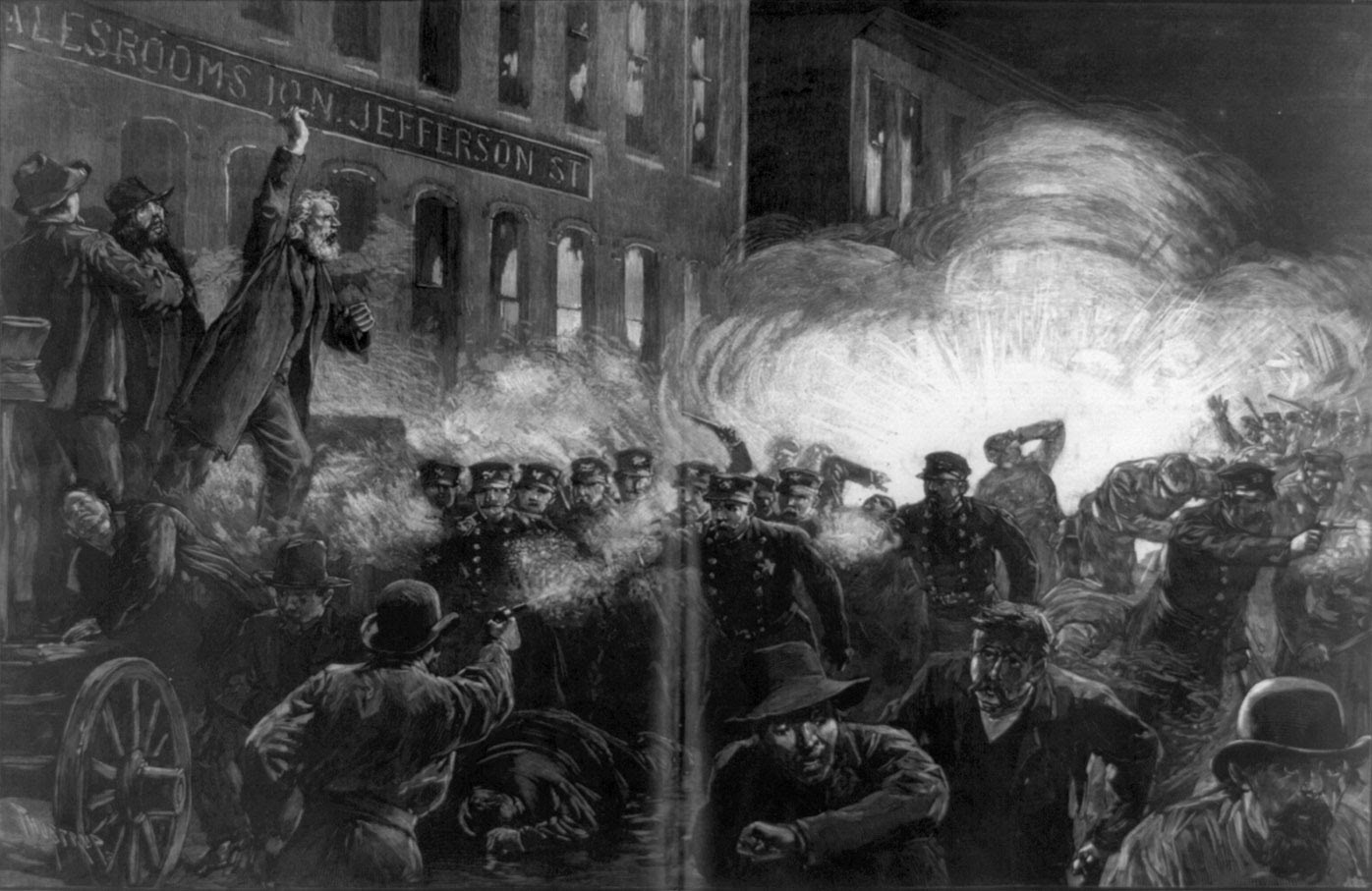

Kim Moody, Tramps and Trade Union Travelers: Internal Migration and Organized Labor in Gilded Age America, 1870–1900. Chicago: Haymarket Books, 2019.

Kim Moody, Tramps and Trade Union Travelers: Internal Migration and Organized Labor in Gilded Age America, 1870–1900. Chicago: Haymarket Books, 2019.

The saying that politics makes for strange bedfellows is a statement that speaks to the many allegiances, alliances and compromises that one must make when engaging in electoral politics. One might think that there could be no more stranger bedfellows in politics than Jackson’s self-proclaimed “radical” mayor Chokwe Antar Lumumba and billionaire and former New York City mayor Michael Bloomberg. However, the alignment of Lumumba and Bloomberg is not so strange at all. State power, as a crossroads of ethnic patronage politics, is not very weird unless we believe that black power means nothing without power to the common people even after people of color retain coveted positions above society. How many of us believe in that today?

The saying that politics makes for strange bedfellows is a statement that speaks to the many allegiances, alliances and compromises that one must make when engaging in electoral politics. One might think that there could be no more stranger bedfellows in politics than Jackson’s self-proclaimed “radical” mayor Chokwe Antar Lumumba and billionaire and former New York City mayor Michael Bloomberg. However, the alignment of Lumumba and Bloomberg is not so strange at all. State power, as a crossroads of ethnic patronage politics, is not very weird unless we believe that black power means nothing without power to the common people even after people of color retain coveted positions above society. How many of us believe in that today?

Doug Henwood, who often has so many intelligent and useful things to say about economics and politics, has it wrong this time. A few days ago on his Facebook page he commented on

Doug Henwood, who often has so many intelligent and useful things to say about economics and politics, has it wrong this time. A few days ago on his Facebook page he commented on

The Boeing Company, a huge global, high tech aerospace corporation has stumbled badly with enormous adverse financial consequences. The Boeing Max 8 tragedy and other corporate tech blunders should encourage us, especially those of us in the labor movement, to develop alternative perspectives and identify important strategic choices.

The Boeing Company, a huge global, high tech aerospace corporation has stumbled badly with enormous adverse financial consequences. The Boeing Max 8 tragedy and other corporate tech blunders should encourage us, especially those of us in the labor movement, to develop alternative perspectives and identify important strategic choices.

2019 was the year when “PMC” entered the vocabulary of many radicals in the U.S. and, to a lesser extent, the rest of the Anglosophere. As

2019 was the year when “PMC” entered the vocabulary of many radicals in the U.S. and, to a lesser extent, the rest of the Anglosophere. As

Word War Two as the death-knell for colonial empires is a well-trodden and essentially erroneous narrative. Empires’ relationships with their colonies were uprooted, modified and given the gloss of ‘independence’ but retained injustice and exploitation at their core. In Central Africa, neo-colonialism is abundant in its forms. This article will explore a particular system of neo-imperial economic exploitation known as the CEMAC zone.

Word War Two as the death-knell for colonial empires is a well-trodden and essentially erroneous narrative. Empires’ relationships with their colonies were uprooted, modified and given the gloss of ‘independence’ but retained injustice and exploitation at their core. In Central Africa, neo-colonialism is abundant in its forms. This article will explore a particular system of neo-imperial economic exploitation known as the CEMAC zone.

President Donald Trump has

President Donald Trump has

Cal Winslow, Radical Seattle: The General Strike of 1919. Monthly Review Press, 2020. 220 pp.

Cal Winslow, Radical Seattle: The General Strike of 1919. Monthly Review Press, 2020. 220 pp.

The Middle East and the world woke up on the morning of Friday, January 3 to the shocking news that U.S. missiles had struck the Baghdad Airport, in a targeted assassination of Iran’s General Qassem Soleimani.

The Middle East and the world woke up on the morning of Friday, January 3 to the shocking news that U.S. missiles had struck the Baghdad Airport, in a targeted assassination of Iran’s General Qassem Soleimani.

The New York Times obituary of neocon historian

The New York Times obituary of neocon historian

I have written at some length about my experience as a member of Workers World Party, which I left due to the organization’s flawed political practice. What I’ve said less about is my psychological and ideological state during this time. If “

I have written at some length about my experience as a member of Workers World Party, which I left due to the organization’s flawed political practice. What I’ve said less about is my psychological and ideological state during this time. If “

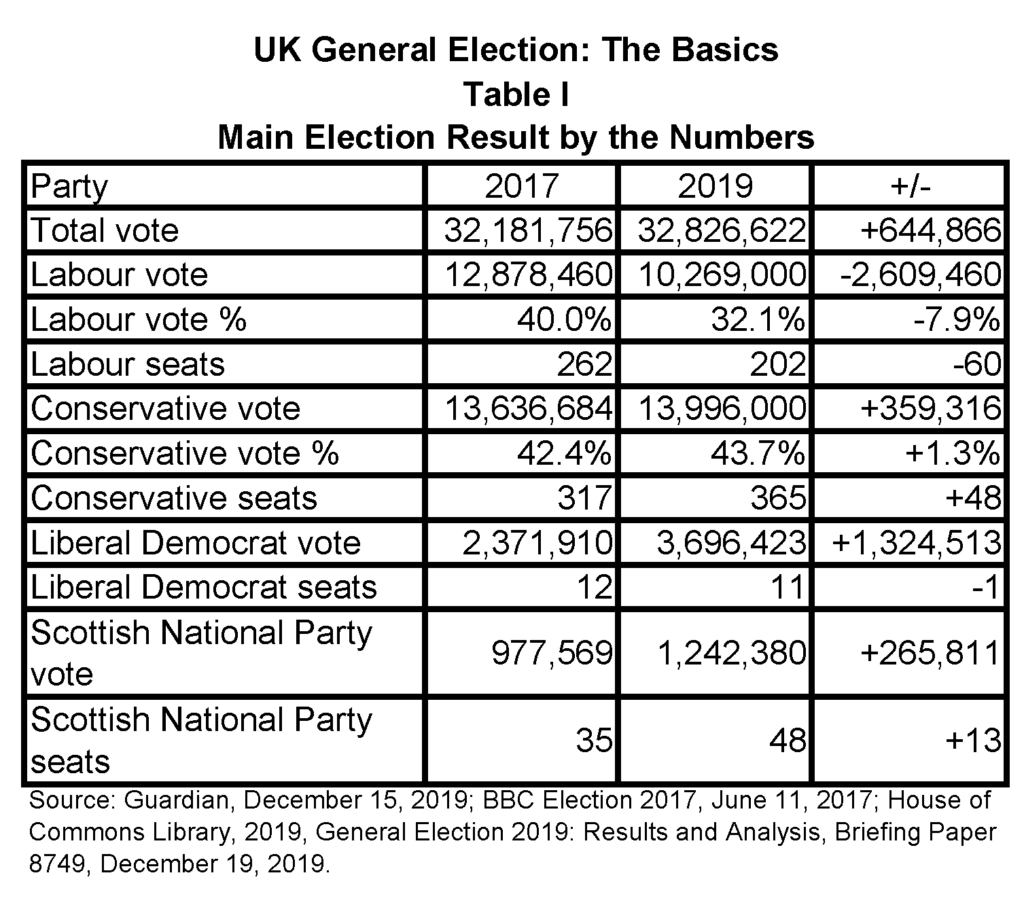

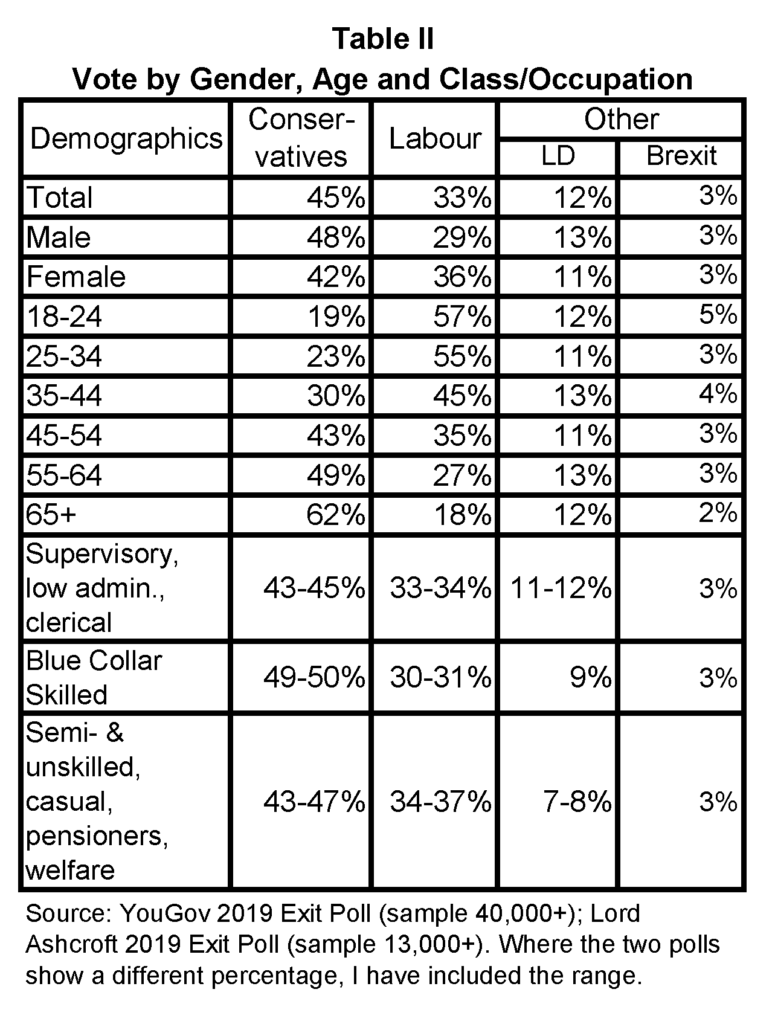

It was probably no surprise that Joe Biden announced that the huge victory for Boris Johnson and the Conservatives and the mauling defeat of Labour under Jeremy Corbyn’s radical leadership was a warning to fellow Democrats to shun the leftism of Sanders and Warren and seek safety in the political center if they hoped to beat Trump in 2020. In fact, in this nasty slugfest between the now seriously right-wing Tory party and left social democratic Labour there was little space for centrists. Despite gathering in a slice of the remain vote, the high hopes of the Liberal Democrats collapsed, their leader lost her seat to the (social democratic) Scottish Nationalists, while all the “moderate” defectors from both main parties who ran as Lib Dems, the Independent Group for Change or as independents lost badly.

It was probably no surprise that Joe Biden announced that the huge victory for Boris Johnson and the Conservatives and the mauling defeat of Labour under Jeremy Corbyn’s radical leadership was a warning to fellow Democrats to shun the leftism of Sanders and Warren and seek safety in the political center if they hoped to beat Trump in 2020. In fact, in this nasty slugfest between the now seriously right-wing Tory party and left social democratic Labour there was little space for centrists. Despite gathering in a slice of the remain vote, the high hopes of the Liberal Democrats collapsed, their leader lost her seat to the (social democratic) Scottish Nationalists, while all the “moderate” defectors from both main parties who ran as Lib Dems, the Independent Group for Change or as independents lost badly.

So, Trump has finally been impeached—or at least sort of. The House voted two articles of impeachment—one for abuse of power for withholding military aid to Ukraine unless it provided Trump with dirt on Joe Biden, the other for trying to undermine Congress’s investigation (it did not however charge Trump with the much more serious crime of obstruction of justice). However, House Speaker Nancy Pelosi has deferred for now sending the articles of impeachment to the Senate because of a dispute with Majority Leader Mitch McConnell over the terms and procedures of the trial to be held there. That suits McConnell and the Republicans just fine, since they don’t want a trial in the first place—even though it is perfectly clear that if one is held they will acquit him on all counts.

So, Trump has finally been impeached—or at least sort of. The House voted two articles of impeachment—one for abuse of power for withholding military aid to Ukraine unless it provided Trump with dirt on Joe Biden, the other for trying to undermine Congress’s investigation (it did not however charge Trump with the much more serious crime of obstruction of justice). However, House Speaker Nancy Pelosi has deferred for now sending the articles of impeachment to the Senate because of a dispute with Majority Leader Mitch McConnell over the terms and procedures of the trial to be held there. That suits McConnell and the Republicans just fine, since they don’t want a trial in the first place—even though it is perfectly clear that if one is held they will acquit him on all counts.

As temperatures dip near or below freezing, scores of Mexican refugees huddle in their makeshift tents of layered plastic sheeting at the foot of the Santa Fe Bridge that connects Ciudad Juarez, Chihuahua, with El Paso, Texas. Many small children form part of the group. No colorfully wrapped packages wait below a Christmas tree. No heart warming lyrics from mariachi singers enliven the site, though a small figurine of the Virgin of Guadalupe watches over the people who wait and wait and wait for their chance to argue a case for political asylum in the United States.

As temperatures dip near or below freezing, scores of Mexican refugees huddle in their makeshift tents of layered plastic sheeting at the foot of the Santa Fe Bridge that connects Ciudad Juarez, Chihuahua, with El Paso, Texas. Many small children form part of the group. No colorfully wrapped packages wait below a Christmas tree. No heart warming lyrics from mariachi singers enliven the site, though a small figurine of the Virgin of Guadalupe watches over the people who wait and wait and wait for their chance to argue a case for political asylum in the United States.

You can’t get the right answers if you don’t ask the right questions.

You can’t get the right answers if you don’t ask the right questions.

This piece is the text of a talk given to the Democratic Socialists of America Lower Manhattan Branch’s Political Education Working Group on December 4, 2019, serving as introduction to “Bernie and Labor” part of its series “Why Bernie?”

This piece is the text of a talk given to the Democratic Socialists of America Lower Manhattan Branch’s Political Education Working Group on December 4, 2019, serving as introduction to “Bernie and Labor” part of its series “Why Bernie?”