We have never seen so many upheavals in so few years in France.

We have never seen so many upheavals in so few years in France.

Society has been turned completely upside down in a way that is totally unprecedented. The social programs won after the Second World War have been savaged and democratic rights won even earlier have been shattered. The executive branch abuses the legislative and judicial branches, thus interfering with governmental checks and balances, and it stifles the role of the media, and dominates society through violent police repression, attacks on freedom of expression, and restricts the right to protest or even to criticize. The radical or extreme right is fully engaged in taking advantage of the openings of the current upheaval and it is the far right that tries to shake things up even more, something that in the past we expected from the far left.

On the other hand, the old leftwing trade union and political organizations are sinking on their own, and many militant trade unionists and even those on the far left are struggling to navigate and to react.

The upheaval is not just French and doesn’t just have to do with Emmanuel Macron, there are also Donald Trump and Prime Minister Boris Johnson in England, Minister of Justice Matteo Salvini in Italy, and others elsewhere. The old Western world is shaking rapidly in ways that work to the advantage of the powerful.

The social movement itself, however, does not remain sluggish or silent, quite the contrary.

The tremendous uprising of the Yellow Vests takes up the glove, reinvents in a thunderclap the class struggle, and by its “uprising,” it invites us to put revolution and the construction of a better world back on the agenda.

We have seldom seen such a mass politicization in so short a time.

In fact, alongside the Yellow Vests, who have been fighting for the last ten months and who are drawing hundreds of thousands of people into the struggle, popular resistance has become massive and diverse, with protests by environmentalists, migrants, women, and the traditional trade union demands. In the wake of the Yellow Vest uprising of the most exploited classes, these other movements are led to ask themselves the question of pushing further their determination and their demands. The bridges between the different sectors in struggle are built, moreover, under the impetus of Yellow Vests. Many understand that there will be no turning back and that it is no longer possible to defend achievements here and there in disparate struggles. Many fighters are slowly gaining confidence in themselves to ask the global question about the society we want and the means to achieve it.

The uprising of the Yellow Vests politicizes large marginal groups and re-initiates the class struggle, its methods, its solutions and develops the class consciousness that has always been built in the most determined struggle. Class consciousness is not something that one finds ready-made or that is transmitted as a treasure from generation to generation. It happens, unfolds, becomes stronger in the course of many varied events, in conflicts that oppose different interests, in the storm, amidst shouts, insults, blows and tumults. It never “defines itself” in an isolated, abstract way but in the concrete struggles by some of its “figures,” by its environment, its edges, its evolution, the people and the organizations that it involves as allies or that it fights.

Class-consciousness can be read in the tactical intelligence of the Yellow Vest movement that aggravates the growing the crisis at the political summit. And this permanent crisis at the top drives the movement as Macron fuels and strengthens class-consciousness and the current uprising. The class-consciousness that is built up through combat and practical experiences is not given as a whole but is lived. It can be first through a sense of class, then a stammering consciousness and finally a consciousness to the end. Moreover, this class consciousness as it becomes fully developed does not invent everything from scratch but is heir to a past common consciousness, the meaning of which we will try to decipher by situating the current movement in the history of the workers’ and popular struggles in recent years in France and describing the consciousness born from it.

Different from the 1930s

The historical scale of the current social and political counter-revolution, led by the bourgeoisie, creates the principal characteristics of today’s social resistance.

Since Macron, we have experienced the destruction of the world in which we have lived since the gains of the popular uprisings that followed the Second World War from 1944 to 1948 and later the events of 1968. There is, of course, continuity between Macron and what began with former French presidents Nicolas Sarkozy and François Hollande as well as their predecessors, but there is also a break. What Macron wants to do—and which is a process underway in the entire Western world—is not quantitative but qualitative.

Macron’s objective isn’t only a question of the legal order, but he wants to change the laws of life itself, to bring about a change in working class mentality, justifying it in all aspects of everyday life even in one’s most personal, intimate experiences.

Nothing says that such a qualitative leap backward is possible or feasible in France, or in the Western world as a whole without major conflicts. We have been living for more than 70 years a daily life based everywhere—in manners, customs, habits, feelings and traditions—on the “social welfare state,” an arrangement that is unique in history. We can hardly imagine a setback of the sort that Macron, Salvini, Johnson and other Trumps would like to inflict upon us without major explosions far beyond what we know today. The struggles of the Yellow Vests give us a little taste.

In fact, we have never known in history such a conjuncture, such a unique moment, or such a brutal calling into question of a way life developed over a very long time. And up until now where there has been such a questioning—one thinks of the 1930s—this only happened when there was a major event, such as an economic crisis or a war, which have enabled the wealthy to justify all their savagery to a fraction of the popular classes themselves plunged into misery and distress. Today, as the entire sovereign state has moved to the right and become more brutal, still we do not see the appearance of mass fascist militias even if small fascist groups are more active and aspire to greater power.

It is hard to imagine the forces state repression alone being able to overcome major social crises of any scale.

The fear of a massive Yellow Vest movement and an explosive social anger can of course push the bourgeois classes to choose the fascist solution. We see this moreover in France since it appears obvious since the demonstrations of September 21, 2019 that the uprising of the Yellow Vests will not stop but on the contrary they bring in their wake other movements, so that the bourgeois press openly gives voice to fascists. But their problem is that it takes men for that and they do not have them in quantity; the small fascist groups can not play that role today. Whenever they tried to go to the streets to oppose the migrants, they mobilized more counter-demonstrators who were more determined than themselves and they had to back down and then give up.

Faced with the rising social unrest, the bourgeois classes are left for the moment with only their police forces and the trade union leaderships. But will they remain reliable if the determination, radicalism and consciousness of the popular classes increase?

Without catastrophic events, like some crisis that would allow a nationalistic or racist deluge to prevail over reason, Macron’s policy seems all the more a “cold-hearted” policy with no real apparent reason…if not that of enriching the richest and perpetuating their capitalist system to the detriment of human beings and the planet. Because, with the destruction of the social and democratic gains, it is also the future of the planet that is at stake. The historical stakes then are double.

Economic disasters can happen, alas, very quickly—and the current warnings about the crisis that is coming are worrisome—but, for now, this is not the case. One can clearly see the chauvinistic and anti-parliamentary attempts to appeal to Johnson’s people with Brexit or Salvini’s racist attacks on the migrants. But we also see their difficulties in realizing their projects “cold,” without justifications of greater scope. The current struggle, therefore, takes place in this time, which gives rise to many resistances and from which in turn there are many awakenings of consciousness.

On the other hand, it is no longer a question, as in the 1930s, of the parties and unions that lead the resistance; there are none today of that type, but rather of the whole social body, infinitely more cultivated and “organized” than in the 1930s, that resists and fights. The social body is very organized by its multiple communication networks, its free time, its means of transport, its general culture, its social protections, all of which makes it terribly effective. Seventy years of the welfare state with protection against sickness, unemployment and retirement—which is certainly not perfect—but which grants between 15 and 20 years of free time at the end of life—that is something which has never been seen before and has effects.

There is no organization, there are no leaders, just a multitude of individuals, small groups and multiple networks—not just on the Internet—that resist and advance. The representatives of power have chained the union leaders to their chariot, but those leaders have lost their authority. The owners would like leaders they could negotiate with, could bribe, or convince to stop, but in the Yellow Vests there are none.

The current uprising eludes them. The water of the movement goes everywhere. This may be a weakness in certain circumstances, as we have seen in Egypt or Tunisia, but it is safe to say that when necessary the uprising will find people within it who are fit for another type of organization. We must also prepare for that.

The Collapse of the Big Business Ideology

The duration of the Yellow Vest uprising, 10 months to date, is explained by the magnitude of what Macron wants to take away from us; the resistances are proportional to what’s at stake.

But the movement’s longevity is also explained by its consciousness, its ability to spot a number of false friends, its ability to avoid the pitfalls and to disbelieve the lies of the powerful, and finally the willingness to understand its own weaknesses. This explains the fierce refusal of the Yellow Vests to build a centralized organization or to have national leaders, in order to prevent such potential leaders from changing sides and turning the movement around. In the same way, their discussions about the Citizens’ Referendum Initiative (RIC) continue, even though most people know very well that no power will permit this, but it is a way of constantly reminding everyone that they no longer believe in the current representative electoral system and its representatives.

What is at the base of this understanding of the collapse of the big business ideology inherited from the preceding period? The big business ideology was founded on three ideological elements that dominated the 1980s and worked against whatever emancipation the workers had won earlier, but they have progressively lost their effectiveness. They are: the fear of a depression, the superiority of the private over public enterprises, and the effectiveness of social dialogue.1

After 1968, the big bosses began to develop a body of thought around the “crisis” and indoctrinated the minds of journalists, thinkers, economists and left- and right-wing politicians, thereby generating a fear that made them accept everything.

Thanks to this fear, big business was able to lay out in a very broad way the solution, namely the importance of the “private sector,” which was supposed to be much more effective than all that is “public” because of its supposed spirit of innovation, its so-called “work ethic,” and its rather hazy “entrepreneurial spirit.” Finally, to attract the employees and chain them to this conception, big business gave a central place to the “social dialogue” and role of union officials to “improve the situation” to the point that business erased the statistics of labor disputes to replace them with the quantification of the employer-worker agreements. According to the employers, labor struggles were no longer necessary, but there was even more! The union leadership to justify this practice of “social dialogue,” let it be said given the supposed absence of struggles they no longer need to report strikes.

As time passed and the attacks got worse, everyone saw from their own experience that this was not a better way, but rather that big business approach brought about a continuous destruction of all the social gains of the past while the business leaders, the bankers, the rich got rich as ever. At the same time, profits and dividends exploded while employers carried out mass layoffs in the name of the “crisis.” At the same time, CEOs received huge salaries and the rich escaped taxes through the growth of tax evasion. The state provided billions in financing for big business while it squeezed the population and destroyed public services.

The crisis was obviously not for everyone. As a result, the crisis served as a mask used to shift the increased exploitation of large numbers of people to the benefit of a minority. In the same way, the so-called superiority of the private sector over the public sector that has been plaguing people’s minds since the 1980s has emerged more and more as the mask of corporate selfishness. The glory of the personal success of the private entrepreneur is now becoming replaced in peoples’ consciousness by the praise of the solidarity that has still been maintained even in a distorted way through the public services and especially by the spirit of public service, a step towards another sort of society. There is an increasing defense of public services—local hospitals, maternity hospitals, emergency services, schools, railway stations, transportation, universities—by employees and by the users as such services are scuttled because of this myth of the superiority of the private sector. Large private entrepreneurs are now seen more as gangsters than as saviors of humanity in a crisis.

In the wake of this realization, the so-called social dialogue between employers, government and trade unions has fizzled out. As a result, the union leaderships appear as complicity with the employers in organizing the decline and paralysis of the employees.

Moreover, while the rigged statistics found a so-called absence of struggles and thus an alleged acceptance of the situation by the exploited, though there had never been as many conflicts breaking out during these years, though they remained invisible to most people. Those struggles brought about a discrepancy in perception between those who experienced them, including many activists, and the commentators or analysts who no longer saw them in the press or the union reports.

Thus, little by little, a spirit of class warfare emerged at the base displacing the reliance on class dialogue at the top. The fear of the crisis was replaced by the hatred of profiteers and the “private.”

Conflicts multiplied in the public services that had been particularly attacked by the governments of Sarkozy and Hollande. The defense of the public services conceived as solidarity and responsibility became the flag of another society, more benevolent and supportive especially toward the weaker and the older, the sick and the homeless, the disabled and the young. The image of the lazy and ineffective public servant gradually gives way to that of the devoted nurse, the brave fireman, the helpful house cleaner …

The ideology of personal success took a hit with the growing sense that future generations will live less well than past generations.

At the same time, a fourth dogma of the ideological system of employers collapsed, that which separated politics from the social, where the first had to do with elections and the second referred to strikes, suggesting that the vote was a best political outlet for social movements. The policies of Sarkozy, Hollande and Macron showed that both the left and the right, in fact, put forward the same policy in the service of the rich. Abstention has become by far the first party in working class and poor neighborhoods, far ahead of all others, including that of Marine Le Pen, head of the right-wing and anti-immigrant National Party. And today, beyond abstention, the idea has developed that the representative bourgeois system is not really democratic and that the movement will require a different electoral system.

The Yellow Vests have inherited this discovery of the bankruptcy of the employers’ ideology. This explains the peculiarity that the Yellow Vest movement began as a protest against rising taxes. Many, seeing this anti-tax movement, which was joined by some employers’ organizations road and right-wing activists, there was the repetition of the earlier Poujadiste. [Pierre Poujade organized an anti-tax movement in France in the 1950s that became politically significant. The Poujadist movement, which hailed the common man, was a rightwing movement that also opposed the decolonization of Algeria and exhibited anti-Semitism. – DL.]

But if some bosses and extreme right groups engaged in this adventure and thought to use it for their own benefit, they quickly turned around and deserted the movement because for the Yellow Vests it was not so much about not paying taxes but about whether or not the taxes would benefit the richest or the poorest people. And besides that, the Yellow Vests carried out an incessant denunciation of those who do not pay their taxes to the detriment of hospitals and schools and hide their money in tax havens.

From 2017 to 2019: The Independence of the Movement and Its Confidence in Struggle

Two major social movement experiences prevailed before the Yellow Vests. First, in the old days, the unions played leapfrog without a global plan of struggle. Then more recently we’ve seen a multitude of struggles that crumbled but within which there developed an awareness of the need for one big struggle, “all together,” though without yet achieving that.

The national agenda of social struggles was dominated by the trade union leaderships and by their days of action. This disjointed agenda was accompanied by its justification: according to the union leadership, the workers would not want to fight.

But the second movement of dispersed struggles proved that that was false, but that could not be heard and could not express itself.

I did my own count and found that more than 4,000 hospitals experienced conflicts and strikes in the year 2017-18. More generally, in all sectors, I recorded 270 struggles and strikes per day in the first half of 2017. This is considerable … but remained invisible in the face of the union steamroller, the media’s silence and the false strike statistics.

In early 2018, a major change took place that would gradually revive the perception of workers’ struggles and the confidence that comes along with them.

In February 2016 the social movement as a whole awakened and took on a new dimension through struggles that have continued until now. But already in 2014, 2015 there had been rank-and-file rebellions in the unions. In their wake there emerged in the spring 2017 the Social Front, an alliance regrouping 200 radical union organizations. During the elections of the spring of 2017 the Front organized events involving up to 20,000 people that targeted candidate for president Macron and the beautiful neighborhoods in which he campaigned, shouting after his election, “One day is enough, Macron must resign.” Against this revolt, the officials of the General Confederation of Workers (CGT), the largest labor federation, and other unions and political parties organized in the fall of 2017 a multitude of scattered, competing, chaotic action days without any plan in order to let off steam. After a few months, activists became discouraged and in November 2017 the CGT called an end to the mobilization, announcing that Macron had definitely won … blaming workers who would not fight. Macron was triumphant, the activists were beaten.

At the end of January 2018, however, against all odds, a new popular mobilization arose. It came from one of the most exploited groups of wage workers and unpaid workers, the most invisible, the least organized, the most feminine and of immigrant origin.

In January 2018, the “zadistes” or squatters occupied a protected nature zone near the airport to force Macron “the invincible” to back down. In that same month, a strike by prison guards broke out, and then there were struggles of high school students and others students across the country; demonstrations by retirees were well attended. and next a growing, angry movement against taxes and the proposed speed limit of 80 kilometers per hour (50 miles per hour) arose in small towns in the provinces among bikers, pensioners, employees of small businesses, independent workers, small craftsmen, the self-employed…

This “angry” movement (which had some 90,000 followers on Facebook) brought together those who opposed the increase in the Contribution Sociale Généralisée (CSG), an income tax, the destruction of pensions, rising prices … and from the many events from February to May. Most of the “angry” group, later came to form the core of Yellow Vests. Already, they had begun to block roundabouts and supermarkets on Saturdays and some were already wearing the yellow safety vests that all French drivers are required to carry in their cars. They brought together some 250 000 people in the most important of their demonstrations. The leadership of the unions of the old workers’ movement began organizing a counter attack by declaring that the angry ones were “fascists”…

In this context, it was the strike of the retirement home workers of Ehpad2 that effectively unified all of the strikes and precipitated the awakening. It began in November 2017, at first invisible to the media, but then activists burst into the open in late January 2018 with more than 2,000 Ehpad workers on strike at the same time. The Ehpad sector was particularly sensitive. It is made of low-wage women workers, precarious, very often provincial, over exploited, often women of color who work in small broken-down structures. Because of its size, it brought to light an important change in the structure of the work in France.

The female proletariat has exploded in number in various sectors—health, cleaning, personal service, fast food or hospitality—bringing together more than 500,000 women at work in the worst conditions, experiencing “Macronian” super-exploitation before it had a name. Although invisible and scorned, it is this sector of women workers whose struggles and victories characterized the period, proving the falsity of the union leadership’s claim that working class was demoralized and demonstrating that those who are at the bottom of the ladder, who are the most exploited, are also often the most determined in the struggle.

This sector is also significant because it imports the struggles of other countries of the world to France (especially from Africa) and adopts and modifies the experience of migrant workers. This is very scary to the authorities who live from their super-exploitation and who assert their political domination through racist demagogy against them. It is significant as well because this is the same super-exploited female working class that will play a key role in organizing the many of the groups and assemblies of the Yellow Vests.

The Ehpad retirement home sector is significant too because of its residents, the seniors. It involves an emotional terrain that affects a large part of the population and also represents a social problem: the inhuman way in which old people are treated in this society. Also, when the Ehpad strike broke out on January 31, it enjoyed a huge boost of popular sympathy and received coverage by local media, which through multiple interviews and testimonies combined the questions of the working conditions of the employees in the sector with the question of the kind of society we want.

Based on this public sympathy, the organizers of the Ehpad strike called for a big national protest on March 15, the day when retirees had already planned to demonstrate. It was a first step towards the convergence of struggles, awakening a new impulse towards a sense of all of us being in this together that could regroup all the angers of the moment and it was beyond the control of the union officials. Immediately, the union leaders put out an alternative call for a mobilization of public services on March 22, while conducting a strong and violent campaign against the March 15 of the Ehpad senior home care workers, even accusing its organizers of sowing division and serving Macron!

The irruption on the social and political scene of the poorest workers took place in a torrential and subversive way from November 17 to December 8, 2018. Faced with this sudden, massive and massive popular surge, the power of Macron wavered and he nearly fell. But he held on. And the uprising of the Yellow Vests held on too. This created an unprecedented situation.

The uprising of the Yellow Vests never regained the strength of its first outburst, but it has lasted a long time and still continues even if it has slowly declined. Having kept its original subversive character, and thanks to that, it continues to have an impact on all of French society by attracting little by little the base of the entire traditional labor movement but also of the activists in the environmental movement and feminists and leads them all to take more radical positions. However, the uprising of the Yellow Vests had no party, no organization or even activists to give a conscious expression of what it was and what it might become. The organizations and most activists of the old workers’ movement—even revolutionary ones—did not join it at first. Hampered by their very defeatist conceptions of the situation, they took a long time to understand what was happening and only finally joined the movement cautiously and belatedly.

Like most Yellow Vests, their spokespeople had never campaigned before. As much as their class instinct was right, they often spoke haltingly in the face of a society whose complexity they had only just discovered. To affect the situation, they had only their momentum, their spontaneity, and their radicalism. They maintained the struggle week after week with stormy demonstrations every Saturday, which earned them fierce police repression. More than 1,000 of them have been sentenced to prison, 400 are still in prison, dozens have lost an eye or a hand, and thousands have been injured in clashes with the police.

Faced with this insurgent “party” in the making—but a party without leaders—the bourgeoisie, in addition to the repression, tried to buy and corrupt the “spokespersons” as soon as they sprouted up or even used its own media to create Yellow Vest “leaders.” To keep its subversive spontaneity, without any help from the old labor movement, the uprising of the Yellow Vests defended themselves by refusing any centralized organization, any national leader, any spokespeople, and authorized keeping a strictly horizontal organization.

The rank-and-file activists of the old workers’ movement became hopeful again. However, the vast majority of them—even those most critical of the trade union leaderships—belong to the most skilled sectors of the working class and have a certain contempt for the less qualified and less organized sectors. Moreover, they do not yet perceive the new global and political dimension of the situation that is taking shape then, as Yellow Vests will express it a little later. And even if the most advanced among them are campaigning for a general strike, they only see it as a classic generalized economic strike. They do not see it as a period when partial economic strikes, the denunciation of a scandalous social situation like that of the elderly, the struggles for a less inhumane prison system, the demonstrations of the students for a better future, or the demonstrations of the retirees in defense of their retirement will altogether form a whole called a general political strike because its logic and its outcome are political and not simply for the obtaining of partial economic demands. They do not see that such a general strike would be about the question of power.

So, instead of supporting both the Yellow Vests’ March 15 demonstration and the labor unions March 22 protest as part of the same movement, the union activists just came out for the March 22 behind the union bureaucracy.

It is also these old social habits and this misunderstanding of the situation that will made these workers accept the slander of the trade union bureaucrats who called the uprising of Yellow Vests a Fascist movement during its emergence, a slander intended to prevent the coming together of the union rank-and-file with the fighting popular uprising during its insurrectional phase from November 17 to December 8, 2018 when the power of Macron wavered (Macron had planned to flee by helicopter from his palace of the Elysée).

At that moment, in March 2018, in the wake of the spirit expressed by the Social Front of 2017, there was a strong desire for a general movement to overturn Macron “and his world” that affected all mobilizations of the moment. Railroad workers, students, electricians, postal workers and leftist activists then went on strike in the spring of 2018, with hope, but without having sufficiently digested the totality of the attacks and the duplicity of the devices they faced. In a few months, the union leaders succeeded in dividing the movement into multiple narrow union struggles carried out through separate strikes, drowning the aspiration to overturn Macron. In early July, the momentum given by the Ehpad retiree home care workers had been dispersed.

Activists were again discouraged and once again the union leaders sang their little song about “the workers not wanting to fight.”

For its part the “angry” movement continued on a parallel path, erased by trade union mobilizations but proposed with the summer holidays to resume its mobilization in October with a new impetus having particularly integrated and matured, the base prepared to overturn Macron and to block the economy, resist the treachery of the union leadership, overcome the inefficiency of leapfrog actions, scattered struggles and negotiations with the government.

The Yellow Vests pull the whole working class forward by raising general class awareness

On the basis of the loss of influence of the business ideology and the awareness gained in the struggles of 2017 and 2018, the uprising of the Yellow Vests added to the loss of confidence in the representative democracy, its police, its system of justice, its elections, and its press and contributed to a growing confidence in the autonomy and capabilities of the working class.

Police violence such as we had not seen in a long time, grew; judicial injustice and its “double standards” depending on whether one is rich or poor, honest-demonstrator or ugly boss; its rigged elections where a president like Macron is elected by only 18% of the registered voters; a press that lies as it always breathes for the benefit of the powerful; all this is no longer written in the underground press of the far left but was seen by millions in the Yellow Vests social media and above all experienced in the street by hundreds of thousands of people engaged in class struggle. Thus we moved from traditional “movements” to an “uprising” to overthrow Macron and his world.

Still, many “protected” social categories still tried to play the old game of “every man for himself” within the system. For example, in the ongoing struggle of hospital emergency physicians, despite having a leadership that escaped the union bureaucracy, they did not try to extend their fight to the rest of the hospital services in struggle. On the contrary, they maintained the hope that the government could give a few billions that would save the service of the emergency physicians. The firefighters’ current struggles are not immune to this approach, nor are those of tax officials and teachers. Employees who have a stable job, a salary and a status, are still trying to save the latter in the general decline.

The Yellow Vests themselves, however, without being deluded, continue to seek an overall convergence. Many Yellow Vests lend their support to the struggles of hospital or firefighters despite the frequent reluctance of the latter and even more often of the trade unions.

Under this influence, these social movements are evolving.

All these movements have the capacity to last a long time, between six months and a year for teachers, hospital agents, tax agents, or firefighters even if the strikes are scattered, fragmented. But this duration translates something and it has effects.

The duration shows that those involved in these struggles are not discouraged. This is one of the striking elements of the situation.

These struggles make one think of long and determined fights against plant closures. But it is the entire public services that are threatened with closure so that there is a displacement of the local struggle to the national struggle but with a “corporatist” character.

At the same time, with the closure of this or that public service, everyone understands that in fact it is a whole type of society that is shut down. This means that the idea is gradually spreading that it is no longer a question of fighting to limit the setbacks while trying to return to the past, but that it is a question of fighting for the future, in short, for another world in which social solidarity would first assert itself and not “the icy waters of selfish calculation.”

This means that the idea is gradually spreading that it is no longer a question of fighting to limit the setbacks while trying to return to the past, but that it is a question of fighting for the future, in short, for another world in which social solidarity would first assert itself and not “the icy waters of selfish calculation.”

Thus after the movement of local struggles was pulverized by “global consciousness,” there appeared a moment of national corporate struggles with the same spirit: we save what we can while waiting to be stronger. These categorical “corporatist” struggles, with the same background of global consciousness, encouraged each other and the whole thing in turn weighed on other sectors trained to do the same, while the duration of the uprising of the Yellow Vests came to affect all of them. And the defense of retirement that began could further amplify this character.

Thus, before others the inter-emergency collective called the entire hospital profession to the common struggle of September 26, at the same time there were a number of joint actions between emergency doctors, Ehpad retirement home care workers, and firefighters, perhaps most notably the national protest on October 15th, always with the presence of: the Yellow Vests.

Teachers’ struggles had also started to emancipate themselves from the union leaderships through the formation of various collectives. Their fight, on October 3 in honor of a teacher who committed suicide at her workplace, took on a general character of a workers’ political response to the government tribute mourning deceased former president of the French Republic Jacques Chirac.

In this context, the tactic of total dispersion of the response by the trade union leaderships during several days of action in September and October had an unprecedented effect and brought new sectors into the process of convergence.

This is what we saw with the strike for retirement at the RATP, the state-owned Parisian public transport system, on September 13 with a rare participation rate of almost 100% and the desire to put defend the retirement benefits by an unlimited strike that began on December 5, 2019.

In addition, on September 13, the public finance workers’ strike in defense of public services reached historic rates of mobilization. The same day, the mobilization of lawyers, pilots, nurses, physiotherapists and liberal health professionals in defense of pensions was massive; same thing again on September 19, with the mobilization of the electricians. The same thing is still happening on the September 21, when the Yellow Vests and ecologists for the climate made that date the first major convergence of struggles; and finally on September 28, the Sound Systems to get justice for Steve Caniço, killed by the police on the night of the Music Festival, brought together 300,000 people in Paris alone, opening the politicization to new environments. And it continues in October, retirees, firefighters, hospital workers …

And then, especially, under the pressure of the rank-and-file, the RATP unions called for an indefinite strike from December 5, followed by sectors of railroad workers, road transport, aviation workers, education … and of course the Yellow Vests supporting this initiative by stating that the defense of retirement or other claims are legitimate … but that to win, we will have to overthrow Macron.

By making the social movement itself push to the end its own political horizons, the Yellow Vests imperceptibly move the social question and raise the larger question of who has the power. By doing so, they aggravate the crisis of classical political representation at the top. They are intensifying the crisis of traditional trade unionism, which has no political perspective, leaving it only a more and more residual place alongside the powers that be. Overall, they are gradually integrating all struggles into this awareness of the need for a general struggle that raises the question of power.

Gradually the laid off workers, the employees of the public services that have been contracted out, the young people without a future, those who have only a small job to survive, the more and more numerous precarious workers, the rejected students, all of these form an immense social soil which, with the Yellow Vests, has become a formidable campaigning ground far exceeding all the organizations.

For the moment, this environment needs a horizontal structure to take control of its destiny, because of its distrust of the union and political machines. But just as for the emergence of the uprising of the Yellow Vests, the massive participation of millions of people in taking control of their own life, any party is useless or even harmful; so too in the final stages of confrontation with power, the regrouping of the initiative and the organization of the forces are vital.

But it is only in the course of the first phase that the party, in the sense of “partisans of one and the same cause,” can understand the situation and the common task that flow from it, at the moment the economic strike, the ecological mobilization, and indignation at the political scandals.

The general strike: the revolution precedes the strike

What is remarkable in this period is that we have had two experiences, one social and the other political. The social experience has gone on since February 2016 when the struggles against the challenges to the labor laws protecting workers began and has been continuous. And the political experience began in November 2018 when the Yellow Vests marched to protest at the presidential palace of the Elysée and that movement has continued for more than 10 months to pose the question of power.

The current uprising is not prepared to end, whether it continues in the form of Yellow Vests or in some other form. Awareness of time is no longer measured in weeks but in months or perhaps years. This duration of the social movement and its growing consciousness become in this situation a deadly element for the Macron regime, a threat which risks dividing the administration on the solutions to be offered.

There is a rise to “something,” to the construction of means for a global response. This is how we can speak of a General Strike in the sense of a period such as Rosa Luxemburg described and as the Yellow Vests and the most conscious militants of this period have understood it. In this General Strike one sees the alteration of failed economic strikes, general or local demonstrations, political struggles, emotions related to scandals, riots, broader strikes, etc. In this period, the politicization of our entire class gives common sense to all the events so far separated, a general march towards a culmination, the seizure of power for a better life. These elements form a whole and this consciousness, pushed to its end, slowly becomes class-consciousness. The current general strike gradually defines its program by integrating the particular battles into a general fight, the dispersed militants adopt general objectives. The strike trains and groups its activists based on its experiences, using all the tools at at its disposal, defeating illusions and the peddlers of illusions along the way, marginalizing trade union leaderships, dissolving their influence on their bases and defining itself and thus forging its own “party.”

In this context, to accelerate the organizational shaping of what historical struggles have brought them, we must call to regroup in the construction of a party all those who have this general awareness of the situation, in order to be, even in the most intense moments, able to give the ultimate power to the current dynamic, to pose the question of power concretely in the most efficient and democratic way.

Jacques Chastaing, September 30, 2019

The French text of this article can be found on Mediapart.

Translation by Dan La Botz

1 “Social dialogue” which might also be translated as “social negotiation” refers to the practice in France of holding high level talks and agreements between the government, the employers and the labor unions, or sometimes just the bosses and the unions. These negotiations often set the terms of wages and conditions, though if the government is also involved, they may also determine the requirements and benefits of social programs. – DL

2 Ehpad = Établissement d’hébergement pour personnes âgées

Much of the world at this moment is a laboratory searching for the cure for capitalism, and the social scientists running the experiments are in the streets.

Much of the world at this moment is a laboratory searching for the cure for capitalism, and the social scientists running the experiments are in the streets.

China moved towards creating a business-friendly environment for private enterprises in the reform and opening up period in the late 1970s. Companies shifted operations and supply chains to China and foreign direct investment poured into the country. However, China’s “unprecedented economic growth” has come predominantly from the exploitation of workers.

China moved towards creating a business-friendly environment for private enterprises in the reform and opening up period in the late 1970s. Companies shifted operations and supply chains to China and foreign direct investment poured into the country. However, China’s “unprecedented economic growth” has come predominantly from the exploitation of workers.

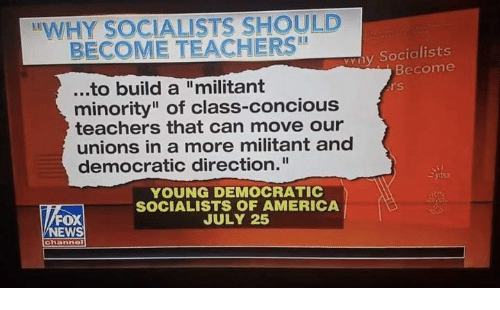

With a new generation of militant radical organizers looking to industrialize into union jobs and kick-start a new militant minority in the U.S. labor movement, their effort is receiving both wide support and wary when not damning criticism. Among the critics is Richard Steier, editor of New York’s weekly the Chief-Leader, whose “Meet the New Left, Just as Daft as the Old Left,” (September 6, 2019,

With a new generation of militant radical organizers looking to industrialize into union jobs and kick-start a new militant minority in the U.S. labor movement, their effort is receiving both wide support and wary when not damning criticism. Among the critics is Richard Steier, editor of New York’s weekly the Chief-Leader, whose “Meet the New Left, Just as Daft as the Old Left,” (September 6, 2019,

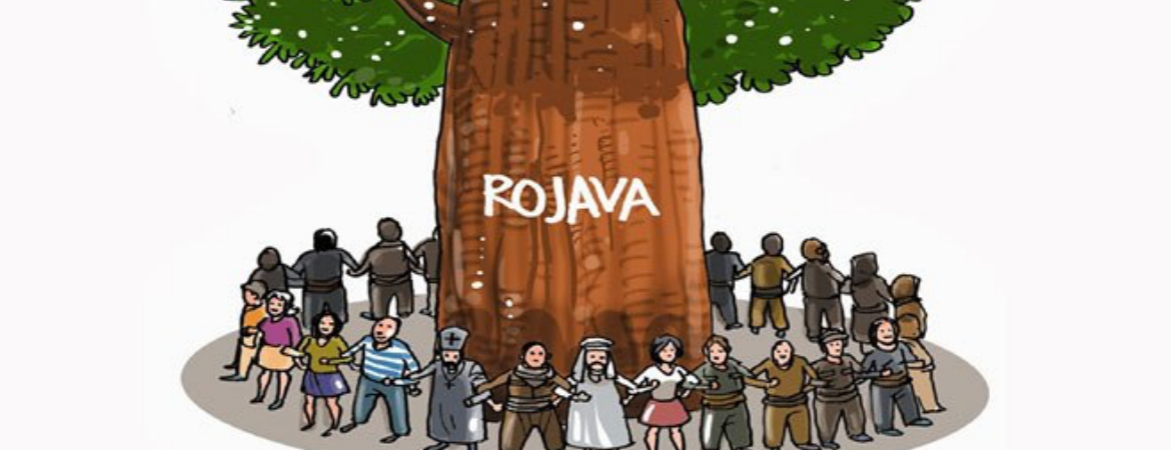

In response to the U.S. troop withdrawal from Syria, decided by the President Donald Trump and his Turkish counterpart Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, and in anticipation of the impending military attack of the free people in Rojava that this deal enables, we consider it urgent and necessary to state the following:

In response to the U.S. troop withdrawal from Syria, decided by the President Donald Trump and his Turkish counterpart Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, and in anticipation of the impending military attack of the free people in Rojava that this deal enables, we consider it urgent and necessary to state the following:

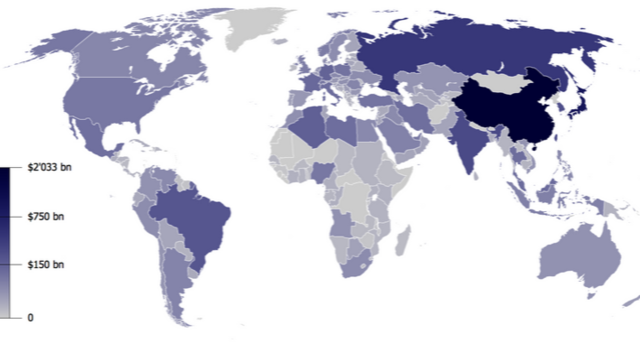

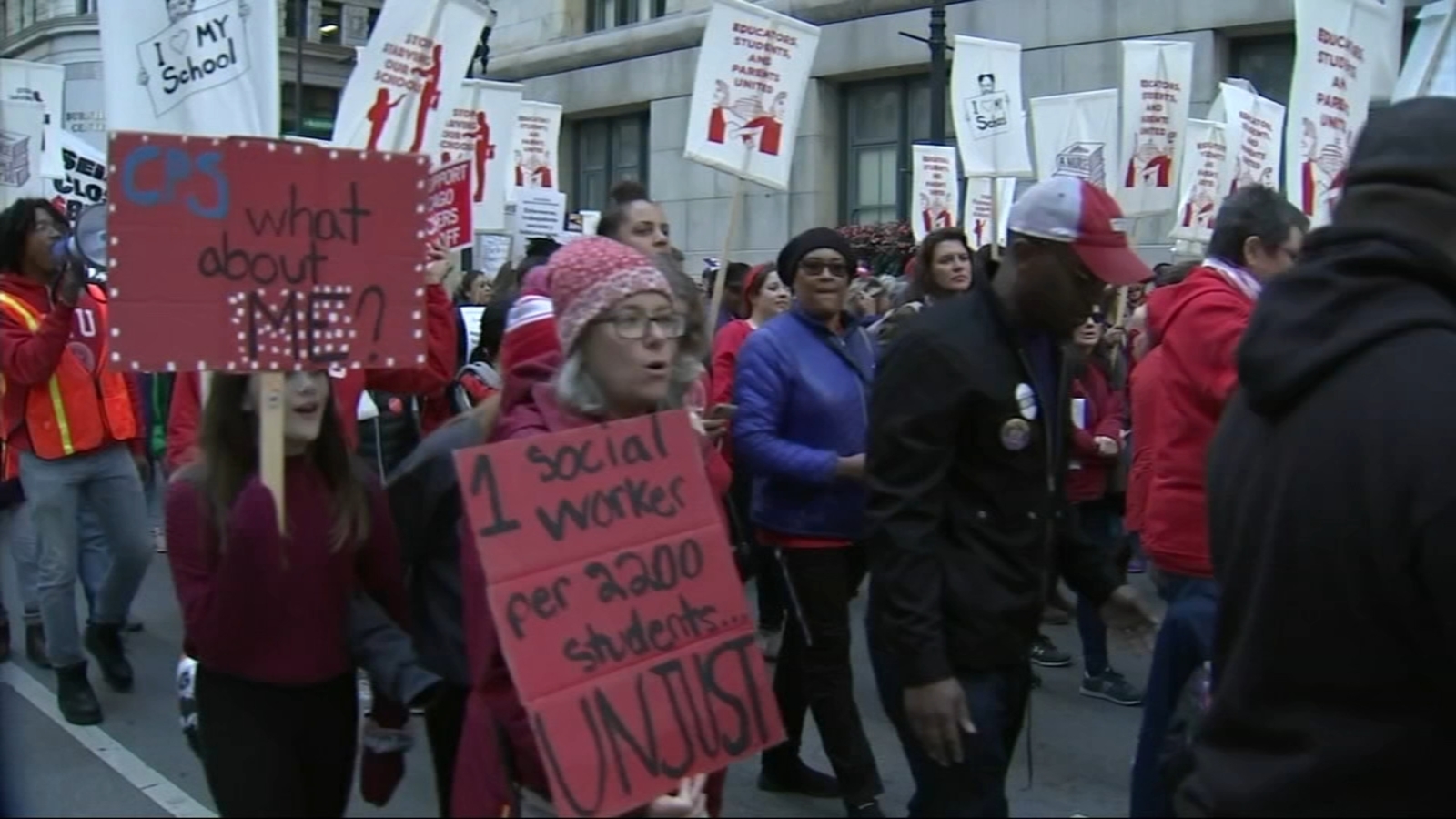

Trade and currency wars, financial volatility and economic turbulence are now the most important features of the world economy.

Trade and currency wars, financial volatility and economic turbulence are now the most important features of the world economy.

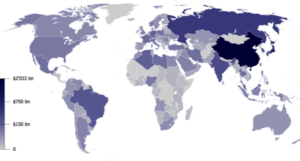

Though the media is casting the strike of education workers in the Chicago Public Schools as (just) another episode in the wave of teachers’ strikes, and the press in Chicago is doing its best to defeat the union, this contract campaign has already set a new bar for resistance to policies on education and the economy in place for decades.

Though the media is casting the strike of education workers in the Chicago Public Schools as (just) another episode in the wave of teachers’ strikes, and the press in Chicago is doing its best to defeat the union, this contract campaign has already set a new bar for resistance to policies on education and the economy in place for decades.

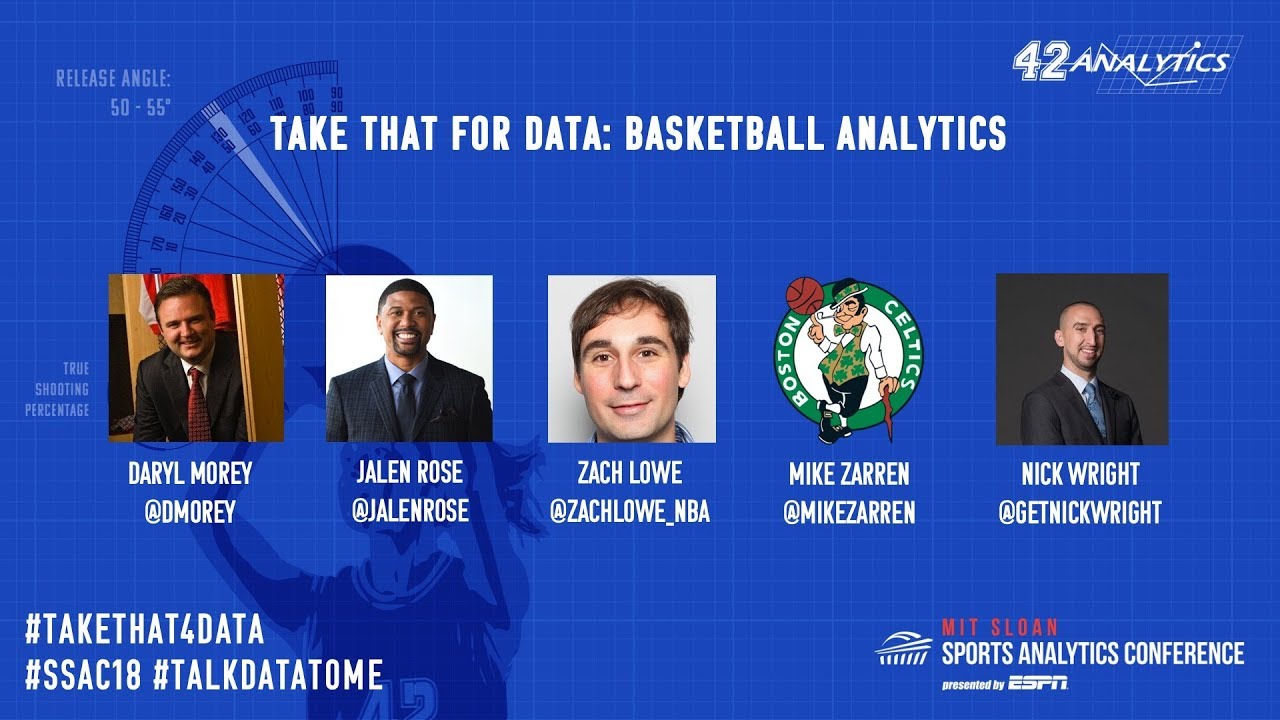

In an interview with the New Yorker this past June, former National Basketball Association (“NBA”) player Jalen Rose criticized the NBA’s ‘data analytics movement’ for how it incentivizes organizations to “funnel jobs” to people with advanced technical degrees, but without basketball experience. Bomani Jones and Pablo Torre subsequently devoted

In an interview with the New Yorker this past June, former National Basketball Association (“NBA”) player Jalen Rose criticized the NBA’s ‘data analytics movement’ for how it incentivizes organizations to “funnel jobs” to people with advanced technical degrees, but without basketball experience. Bomani Jones and Pablo Torre subsequently devoted

When I was working with the Teamster reform movement forty years ago, truck drivers concerned about union corruption had to proceed warily.

When I was working with the Teamster reform movement forty years ago, truck drivers concerned about union corruption had to proceed warily.

On October 9, Turkish armed forces began bombarding Rojava, the autonomous self-governing Kurdish enclave in northern Syria and are poised to cross over with ground troops as well. This attempt to wipe Rojava off the map is the product of a dirty deal between Turkey’s Recep Tayyip Erdogan and Donald Trump. In giving the green light to Erdogan, Trump has pulled the rug out from under the very forces that have done to most to defeat and contain the Islamic State.

On October 9, Turkish armed forces began bombarding Rojava, the autonomous self-governing Kurdish enclave in northern Syria and are poised to cross over with ground troops as well. This attempt to wipe Rojava off the map is the product of a dirty deal between Turkey’s Recep Tayyip Erdogan and Donald Trump. In giving the green light to Erdogan, Trump has pulled the rug out from under the very forces that have done to most to defeat and contain the Islamic State.

Gutter journalism is unfortunately not the preserve of openly right-wing tabloids. There has existed since the advent of Stalinism a “left-wing” strand of public mudslinging: Zhdanov was the counterpart of Goebbels. The Stalinist slander apparatus originally targeted the USSR’s left-wing critics, who were labelled “Hitlerists” in the 1930s-40s and “CIA agents” thereafter. This tradition did not vanish, alas, with the demise of the Soviet Union, although it has much less impact nowadays than it used to have when the Stalinist state’s propaganda machine was behind it at full blast.

Gutter journalism is unfortunately not the preserve of openly right-wing tabloids. There has existed since the advent of Stalinism a “left-wing” strand of public mudslinging: Zhdanov was the counterpart of Goebbels. The Stalinist slander apparatus originally targeted the USSR’s left-wing critics, who were labelled “Hitlerists” in the 1930s-40s and “CIA agents” thereafter. This tradition did not vanish, alas, with the demise of the Soviet Union, although it has much less impact nowadays than it used to have when the Stalinist state’s propaganda machine was behind it at full blast.

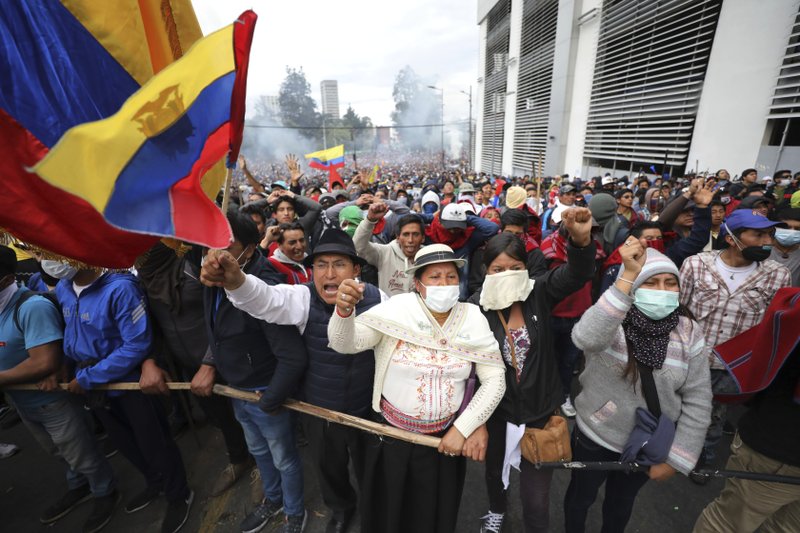

We, the women who resist – in the streets, in our territories, from our spaces and communities – we are the feminist sisters from Abya Yala, those who combat with our bodies, and sustain life; We sympathize with the criminalized, detained, repressed and persecuted in these days of protest against the neoliberal economic measures (paquetazo) of Lenin Moreno´s government. Since the announcement on Tuesday, of the structural adjustment measures in Ecuador, the different organizations and popular movements, indigenous and social, called for an indefinite strike against the economic violence exerted by the Government / International Monetary Fund / Business Partnership, that fundamentally affects the popular sectors, the most impoverished and the middle classes.

We, the women who resist – in the streets, in our territories, from our spaces and communities – we are the feminist sisters from Abya Yala, those who combat with our bodies, and sustain life; We sympathize with the criminalized, detained, repressed and persecuted in these days of protest against the neoliberal economic measures (paquetazo) of Lenin Moreno´s government. Since the announcement on Tuesday, of the structural adjustment measures in Ecuador, the different organizations and popular movements, indigenous and social, called for an indefinite strike against the economic violence exerted by the Government / International Monetary Fund / Business Partnership, that fundamentally affects the popular sectors, the most impoverished and the middle classes.

We have never seen so many upheavals in so few years in France.

We have never seen so many upheavals in so few years in France.

Much has been made of a supposed leftward shift in the Democratic Party over the last three years. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, Ilhan Omar, Ayanna Pressley, and Rashida Tlaib, four new Democratic congresswomen known as “the Squad,” began capturing widespread media attention, many treated the 2018 midterm elections where Democrats won the House as a turning point for the party, where the left wing of the party was on the rise, leaving the Third Way era behind. A new strategy began to be promoted and championed by groups like the Justice Democrats, that of challenging incumbent Democrats in safe-blue districts with volunteer armies from a group we’ll call progressive activists, borrowing a term from

Much has been made of a supposed leftward shift in the Democratic Party over the last three years. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, Ilhan Omar, Ayanna Pressley, and Rashida Tlaib, four new Democratic congresswomen known as “the Squad,” began capturing widespread media attention, many treated the 2018 midterm elections where Democrats won the House as a turning point for the party, where the left wing of the party was on the rise, leaving the Third Way era behind. A new strategy began to be promoted and championed by groups like the Justice Democrats, that of challenging incumbent Democrats in safe-blue districts with volunteer armies from a group we’ll call progressive activists, borrowing a term from

When 16-year-old climate activist Greta Thunberg ascended to the helm of climate politics, the American right naturally assumed that her words were leveraged at them. And who could blame them? As the only major group of people on the planet still in denial about the impending ecological crisis, American conservatives are paranoid that every mention of climate change is a rhetorical assault on conservatism itself. Fox News and the like responded by comparing this 16-year-old girl to the Children of the Corn and by calling her “mentally ill” in a not-so-surprising display of tasteless insults and ad hominem attacks.

When 16-year-old climate activist Greta Thunberg ascended to the helm of climate politics, the American right naturally assumed that her words were leveraged at them. And who could blame them? As the only major group of people on the planet still in denial about the impending ecological crisis, American conservatives are paranoid that every mention of climate change is a rhetorical assault on conservatism itself. Fox News and the like responded by comparing this 16-year-old girl to the Children of the Corn and by calling her “mentally ill” in a not-so-surprising display of tasteless insults and ad hominem attacks.

With Democratic primary campaigns in full-swing and the 2020 election just over a year away, I thought I’d take a look at some of the reports on available data that could shed light on the motives and actions of the American electorate in 2016. In particular, I wanted to consider which observed trends seemed to play a role in the unlikely victory of Donald Trump in 2016 to think about which candidate (or candidates) would have the best shot of beating him in 2020. Of course, just because there was an observable voter trend in one election does not mean it will repeat four years later. Also, it’s certainly possible that unforeseen developments or turnout (or lack thereof) from some un-predicted composite of voters could affect things in unforeseeable ways in 2020. So, in short, one never knows for sure. The outcome of the 2016 election is itself an indication of this. This is not an attempt to exhaustively flesh out substance from numbers or a consideration of every possible theoretical contingency. Rather, it’s simply a little dip into some data and a bit of reflection.

With Democratic primary campaigns in full-swing and the 2020 election just over a year away, I thought I’d take a look at some of the reports on available data that could shed light on the motives and actions of the American electorate in 2016. In particular, I wanted to consider which observed trends seemed to play a role in the unlikely victory of Donald Trump in 2016 to think about which candidate (or candidates) would have the best shot of beating him in 2020. Of course, just because there was an observable voter trend in one election does not mean it will repeat four years later. Also, it’s certainly possible that unforeseen developments or turnout (or lack thereof) from some un-predicted composite of voters could affect things in unforeseeable ways in 2020. So, in short, one never knows for sure. The outcome of the 2016 election is itself an indication of this. This is not an attempt to exhaustively flesh out substance from numbers or a consideration of every possible theoretical contingency. Rather, it’s simply a little dip into some data and a bit of reflection.

In

In

Who could have missed Ayman Odeh’s eloquent op-ed piece in the New York Times, where he rightly asserted that “Arab-Palestinian citizens have chosen to reject Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, his politics of fear and hate, and the inequality and division he advanced for the past decade”? Or his explanation of why he and the coalition he leads chose to nominate Benny Gantz—an IDF chief accused of war crimes against fellow Palestinians—for prime minister. It was on this promise, and with the full knowledge that the Joint List will never be part of the emerging future ruling coalition, that sixty percent of Israel’s’ Arab citizens voted, making the Joint List coalition of Palestinian-Arab-led parties the third-largest list in the Knesset and the leading oppositional force in Israel.

Who could have missed Ayman Odeh’s eloquent op-ed piece in the New York Times, where he rightly asserted that “Arab-Palestinian citizens have chosen to reject Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, his politics of fear and hate, and the inequality and division he advanced for the past decade”? Or his explanation of why he and the coalition he leads chose to nominate Benny Gantz—an IDF chief accused of war crimes against fellow Palestinians—for prime minister. It was on this promise, and with the full knowledge that the Joint List will never be part of the emerging future ruling coalition, that sixty percent of Israel’s’ Arab citizens voted, making the Joint List coalition of Palestinian-Arab-led parties the third-largest list in the Knesset and the leading oppositional force in Israel.