“The problem with Americans is they think something is better than nothing.”

“The problem with Americans is they think something is better than nothing.”

– Alfred Stieglitz

“Carbon capture is total bullshit.” – Michael Bloomberg

Capitalizing on D-Day to peddle U.S. oil (which he still thinks is his job), Rick Perry told the European Union:

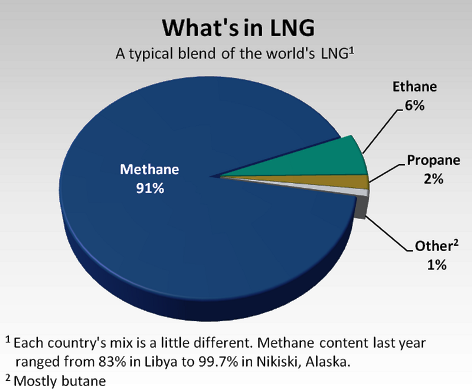

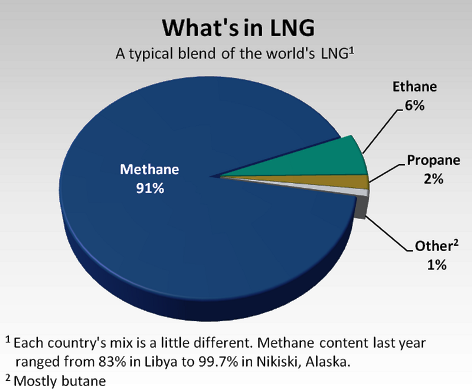

Seventy-five years after liberating Europe from Nazi Germany occupation, the United States is again delivering a form of freedom to the European continent. And rather than in the form of young American soldiers, it’s in the form of liquefied natural gas.[1]

Of course, it’s nonsense. U.S. CO2 emissions are 8X the EU’s highest producer, Germany, and 15X-150X the rest. Following our lead would increase pollution. And pollution takes freedom away.

But put that aside. Consider his analogy — if it’s analogy. Almost 75 years after Nazi Germany fell, and almost 30 after the Cold War there remain over 60,000 US troops in Europe, 170,000 abroad, and U.S. bases in over 150 countries. Not to mention we still have 30,000+ nuclear missiles aimed round the world.

I suspect remaining occupied took the shine off liberation. But if one needs convincing, since WWII we’ve toppled more than a dozen governments and tried in at least 50 other cases. That’s not counting how many times we’ve simply meddled (numbers might not go that high.)[2]

Still, America’s held fast to the title of “liberator.” At least enough to fool (if not everyone) a voting majority of Americans, and to keep a mostly straight face when talking to the rest of the world. Yet we can’t earnestly say we’ve helped, considering the outcomes. Nor even meant to, considering the means; ecocide in Vietnam, more bombs on Baghdad than on the Axis Powers, etc.

It’s boggling we all haven’t died of freedom, already. 75 more years would kill us for sure. Burning fossil fuels at our current rate would heat the Earth at least four degrees by 2100. 75% of us – about 8.4 billion people – would face 20 or more days of deadly heat per year.[3] In comparison, on average 12 million – 0.6% – died per year in WWII.

Looking back, gas may have “liberated’”America. At least it made U.S. industries exceedingly rich. Investors pumped post-war capital back into America, mainly through sprawl. Cars meant freedom from the crisis of our cities that their rigged market was busy inventing. But since it entailed guzzling a quarter of the world’s oil, we obviously didn’t -then- plan to free anyone else. On the contrary, some we produced, but the rest we got cheap by knocking over other oil-producing countries, starting with Iran in 1954. One recalls ‘the humanity’ with which we freed Iraq in 2002.

Of course, no country stays “great” forever. America’s social progress has declined 40% since the post-war heydays. If Perry’s goal is to export “freedom,” bear in mind we now rank 10th, according to the UN. Not the worst, but hardly a blueprint. And to unpack that, we rank 19th in mobility, 19th in happiness, 48th in press freedom, and 64th in life-expectancy. We have the 4th-highest income disparity, and the highest incarceration.

Free the world? We might finally be ready. Perry was in Europe to sign agreements that would double the amount of gas we sell them. But consider – before 2008 U.S. production was in decline. It’s nearly tripled since, thanks to a financial coup that poured capital -that otherwise wouldn’t have gathered – into fracking. JP Morgan, Citigroup, Wells Fargo (and others) each lent hundreds of millions of (our) dollars to the nascent industry, before it was proved either safe or profitable. So, besides indebting us, evicting us, killing our democracy, and other kicks to the gut, bailouts spurred global warming.[4]

Now that we’ve figured how to gut our own country our trips abroad are more to open markets than taps (though it still spills blood). Mind, fracking was sold to us as a path to energy independence, which implied cheaper costs, but also fewer fiascoes like the Iraq War. Now we are the world’s #1 oil producer, and the bulk of it gets exported. (And we still import.) NAFTA has made great strides addicting oil-rich Mexico to our gas, about 2/3 of all exports. The remaining 1/3 scatters to China, Russia, and 30 other countries.

Bolton unabashedly claims we want access to Venezuela’s oil. But, ironically, Chavez brought electricity to the poor of Caracas, and now they’re in need of fuel to power it. Violating the spirit of our own embargo, we’ve been selling oil to Venezuela since 2015. Not really violating. The embargo, as intended, has opened a hostage market. At the cost of more than a few lives.

Perry may be dim, even for a Trump swampling. He named his ranch “Niggerhead” and couldn’t count to five on TV (whoops!). And he took his Energy Secretary job without knowing what it was. (Hope no one’s squeamish; it’s managing our nuclear weapons.) But, like his boss, he’s just what the mostly liberal 1% needs. Someone to perform the terrors that secure their petrol-empire, yet won’t get caught winking at them afterwards.

As Perry’s words belie, global warming is a bigger political hurdle than a technological or economic one. Is there a political solution?

Well, history is rife with ruling classes that chose catastrophe over yielding a bit of their power. 2016 was plenty convincing; ours would prefer losing to the four horsemen than to even modest reformers. For a more current example, the mainstream version of the Green New Deal hardly seeks to abolish capitalism. On the contrary, it’s predicated on private green growth. Yet it gets stonewalled by entirely political accusations of socialism.

Ominously, the point was and remains to avoid a political crisis, to profit second, and our survival is tertiary, at best. But that’s not to protect the economy, if by economy you mean the common market. Because we know for sure global warming will hurt it more. Rather there’s the political economy, which right now is defined by the 1% and the .001% through tax structures and regulatory policies that privilege them, almost beyond measure.

Yes, almost. We estimate U.S. fossil fuel subsidies are between 20 and $50 billion per year. That does not include the social costs of pollution the industry avoids, which research out of Stanford University puts at $220 per ton, or $1.76 trillion, annually.[5] Subsidies, held-fast by a client-government. For measure, 22 of the 55 Congressmembers on the Committee assigned to address global warming hold stock in fossil fuels to the tune of at least $16 million.[6]

Together, business and government protect their hill with two lines of bullshit: Technology and Economics. And these turn into more world-eating boons.

For example, the alleged center-path between Trump’s nihilism and Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez’s so-called socialism draws heavy on carbon capture. Problem is, not a soul, including the industry lobby/ alleged authority, the Carbon Capture Coalition (CCC) believes carbon capture reduces emissions. In their words, carbon capture “extends domestic oil production” and “achieves significant CO2 emissions reductions from oil, natural gas, coal, and ethanol and from key industrial processes essential to modern society.”[7]

Significant? Direct air capture, despite its scale and expense (what attracts the industry) could reduce global emissions by at most 2%. And prior to that, carbon storage would require a nation-wide grid of pipelines to move the CO2 from the capture facilities to proper geological caverns. Then it would take several hundred years of constant vigilance to ensure it doesn’t escape.[8]

Moreover, large scale implementation would slow the transition to renewables. In fact, most captured CO2 is used for fracking. Compressed CO2 is injected into depleted reservoirs, inflating and pushing oil upward for extraction. In other words, its introducing new oil worth an estimated 90% of its own carbon back into the air, in a continuous cycle.[9]

Moreover, government funding for carbon capture is helping the fossil fuel industry build new infrastructure. Last year the CCC-authored 45Q Bill expanded tax credit for carbon capture. This year the Coalition gifted Senate the Use It Act, which, if passed, allots Federal and State Resources for building pipelines to transport carbon, again, most to oilfields.

Another policy think tank, the Carbon Capture & Storage Association (CCSA), an arm of BP, says its crucial for governments to fund carbon capture. However, BP says it will not undertake “material” projects without government funding.[10]

Spencer Dale, BP’s chief economist, just released a report warning us against relying on green options. Renewable energy would have to grow at twice its current rate just to offset our coal use. According to Dale, the same could be achieved by replacing a mere 10% of coal energy with natural gas.

Of course, replacing all coal plants with new gas plants will not cut emissions by nearly enough to keep temperatures under +2.5 degrees.[11] Not to mention, doubling our rate of transition to renewables is entirely within reach, and full transition isn’t far, cost-wise, beyond what we’d recover by ending fossil fuel subsidies. Reforming our upper tax bracket would supply the rest.

If we need further convincing, Perry just awarded $24 million in Federal Grants for carbon capture research, so clearly, it must not work. However, Trump just lifted Obama’s order that coal plants use it, which doesn’t bolster gas use at all. If he goes far too far, liberals might retake the Hill. Good thing we have Democrats to oppose him.

…Right?

Joe Biden’s environmental plan “could include fossil fuel options like natural gas and carbon capture technology, which limit emissions from coal plants and other industrial facilities.” However, Biden had to retract his first draft of said plan because it literally plagiarized the Carbon Capture Coalition!

Kirsten Gillibrand’s website brags of her and Chuck Schumer procuring $1.2 million for the Pall Corporation for Carbon Capture Research.

Cory Booker helped procure $800 million for Princeton Research on the matter.

Michael Bennet recently co-sponsored a bill, the Carbon Capture Improvement Act, that would allow businesses to use private activity bonds (PABs) issued by local or state governments to finance a carbon capture project. He quotes: “This is significant step to ensure we…keep our air clean as the threat of climate change continues to grow.”[12]

John Hickenlooper, who calls himself a scientist, will also begin “large-scale investment in government-funded climate technology research. …One of the pathways is to invest in carbon capture, utilization, and storage technology.” “The market,” he adds, “is the key, not the enemy.”

Beto O’Rourke’s plan isn’t crystal clear, but his website promises more than $1 trillion in tax incentives to “accelerate the scale up of nascent technologies enabling reductions in greenhouse gas emissions.”

Most deliriously, John Delaney “will make rural and heartland America the center of a massive new industry – carbon capture.” According to his website a “$15 (tax) per metric ton of CO2 with costs rising $10 per year will reduce carbon emissions by 90% by 2050 while virtually eliminating rural poverty.”

All seven received oil money for their campaigns.[13]

Carbon capture does have one high-ranking critic. “Carbon capture is total bullshit” according to Michael Bloomberg. Bloomberg just pledged $500 million (.00009% of his wealth) to carbon neutrality. The money will go to “influencers”, including personalities, think-tanks, etc. as well as politicians, active against fossil fuel.

Bloomberg also chairs the Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures (FSB) which urges companies to self-report their carbon emissions. The gist is (in a presumably greening market), disclosure warns investors of your long-term viability. Thus, discharging less CO2 increases your value. In his words, “Increasing transparency makes markets more efficient, and economies more stable and resilient.”

Maybe. A small aside, but does someone who funds “influencers” to the tune of $500 million seem faithful that transparency’ is a climate solution? Or think; Bloomberg’s partner, Diana Taylor is a board member of Citigroup. As we mentioned, Citigroup has poured hundreds of millions in taxpayers’ money into fracking with no market repercussions, and in fact, no disclosure from her or Michael Bloomberg.

And why should we place our fate in the hands of stockholders to police corporations? We are talking about the same group of people. 40% of all stocks belong to the top 1% and the top 10% hold almost 90%. Moreover, since Trump’s tax break, companies have spent most of their winnings buying back their own stock. Some are on their way to becoming their own majority shareholders.

More likely, since data is a hot commodity, and data is what they’re collecting, a little transparency should enhance their skill, not discourage it.[14] Fact is, we used more energy last year because it was hotter. Global warming may be growing the fossil fuel industry! A “stable and resilient” fossil fuel economy might kill us faster than coal’s last hurrah will under Trump.

In sum, it’s hard to overstate capitalism’s debt to fossil fuels. Only with large scale coal operations did free labor out-profit slavery. Only with oil was it able to manufacture at rates that reduced the cost of both goods and labor without killing the workers, as 19th century coal industries had. Only with the advent of cheap manufactures like plastic could the poor routinely consume beyond needs, opening new markets. Post-war atomization coerced more buying, but more buying takes either more income or lower prices. Since higher wages don’t easily translate to higher profits. Only by opening less-advanced markets -made possible by cheap global transportation- could they lower prices. And only with the petrol-dollar could the arch-capitalist U.S. maintain this hegemony after WWII reconstruction. And when it tottered, fossil fuel proved “too big to fail.”

Expect, the same next time, when it’s a life system, not just a financial one. In 2020, peddling a fake cure isn’t bullshit, it’s genocide. Calling genocide bullshit – when you have billions of dollars in your account – is genocide too.

Hell awaits them. They didn’t have to bring it here.

[1] https://www.euractiv.com/section/energy/news/freedom-gas-us-opens-lng-floodgates-to-europe/#link=%7B%22role%22:%22standard%22,%22href%22:%22https://www.euractiv.com/section/energy/news/freedom-gas-us-opens-lng-floodgates-to-europe/%22,%22target%22:%22%22,%22absolute%22:%22%22,%22linkText%22:%22according%20to%20EURACTV%22%7D

[2] https://williamblum.org/essays/read/overthrowing-other-peoples-governments-the-master-list

[3][3]https://www.nature.com/articles/nclimate3322.epdf?referrer_access_token=49vVZLvYYRvoLhM598ayH9RgN0jAjWel9jnR3ZoTv0P1ZmqVLxKfxqQX-KqJzVRLBBVboAWW8gu7iH3qRbNOyoSZixdvmecfrM29-bZ-9tEU1PEFzZfG3TQ61hdmfmv00c_K7lE3ReGyKmPOWLzD_HFhfaQmzAdL8H7tUQA_pxo_jSp_PXhN52wXbsIdFDBvbeWZlisFjktbszXDBkrvVQ%3D%3D&tracking_referrer=news.nationalgeographic.com

[4] https://newrepublic.com/article/151700/bank-bailout-hobbled-climate-fight

[5]https://www.yaleclimateconnections.org/2015/02/understanding-the-social-cost-of-carbon-and-connecting-it-to-our-lives/

[6] https://readsludge.com/2019/01/30/members-of-house-committee-overseeing-the-environment-have-millions-invested-in-fossil-fuels/

[7] https://carboncapturecoalition.org/about-carbon-capture/

[8] https://www.climateliabilitynews.org/2019/03/13/carbon-capture-fossil-fuels-ciel-report/

[9] ibid.

[10] https://www.theguardian.com/business/2019/jun/11/energy-industry-carbon-emissions-bp-report-fossil-fuels

[11] http://priceofoil.org/2019/05/30/new-report-debunks-gas-bridge-fuel-myth/

[12] https://www.bennet.senate.gov/public/index.cfm/2019/6/bennet-portman-reintroduce-bill-to-reduce-overall-carbon-emissions-and-boost-domestic-energy-production

[13] https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/ng-interactive/2019/jun/20/democrats-2020-fossil-fuel-donations

[14] https://newpol.org/microsofts-plan-ai-runs-on-gas/

As the Indian government resorts to annexation of the state of Jammu and Kashmir at gunpoint, detaining its political leaders and cutting off all means of communication, we extend our solidarity to the people of Jammu and Kashmir as they struggle for their most basic rights and freedoms.

As the Indian government resorts to annexation of the state of Jammu and Kashmir at gunpoint, detaining its political leaders and cutting off all means of communication, we extend our solidarity to the people of Jammu and Kashmir as they struggle for their most basic rights and freedoms.

Ecosocialists must stand in support of the millions of democracy protesters in Hong Kong and call on American trade unions and the left to join us. The Chinese Communist Party is on a suicide mission to destroy planet Earth in its all-out drive to maximize economic growth to save the party-state ruling class even if that growth produces CO2 emissions that precipitate planetary ecological collapse. China’s emissions are already more than twice as large as those of the U.S. and growing, with a GDP just 63 % the size of the U.S. The Communist Party cannot rein in those emissions in because cutting emissions means cutting growth and even the slightest economic slowdown threatens their grip on power. Xi Jinping already faces wide and growing opposition to his policies which is why he’s cracking down so brutally, jailing dissidents, democrats, trade union activists, Marxist students, feminists, locking up millions in “re-education” concentration camps in Xinjiang and Tibet, and openly threatening to massacre Hong Kong democracy activists as Deng Xiaoping did 30 years ago in Tiananmen.

Ecosocialists must stand in support of the millions of democracy protesters in Hong Kong and call on American trade unions and the left to join us. The Chinese Communist Party is on a suicide mission to destroy planet Earth in its all-out drive to maximize economic growth to save the party-state ruling class even if that growth produces CO2 emissions that precipitate planetary ecological collapse. China’s emissions are already more than twice as large as those of the U.S. and growing, with a GDP just 63 % the size of the U.S. The Communist Party cannot rein in those emissions in because cutting emissions means cutting growth and even the slightest economic slowdown threatens their grip on power. Xi Jinping already faces wide and growing opposition to his policies which is why he’s cracking down so brutally, jailing dissidents, democrats, trade union activists, Marxist students, feminists, locking up millions in “re-education” concentration camps in Xinjiang and Tibet, and openly threatening to massacre Hong Kong democracy activists as Deng Xiaoping did 30 years ago in Tiananmen.

The restriction of academic asylum in Greece under the new right-wing government has become – again – the epicenter of an intense debate. The debate over academic asylum has both a pretense and a rationale. The pretense is about “safety and order.” The reason is the ending of safe spaces for progressive ideas in Greek Universities, something that every reactionary government wishes to end to restrict democracy.

The restriction of academic asylum in Greece under the new right-wing government has become – again – the epicenter of an intense debate. The debate over academic asylum has both a pretense and a rationale. The pretense is about “safety and order.” The reason is the ending of safe spaces for progressive ideas in Greek Universities, something that every reactionary government wishes to end to restrict democracy.

The intense revulsion over the horrific slaughter in El Paso has shifted politics. But beware of ruling class solutions to crises caused by the ruling class.

The intense revulsion over the horrific slaughter in El Paso has shifted politics. But beware of ruling class solutions to crises caused by the ruling class.

The left and labour movement has always been the subject of state repression. The failure of the Peterloo massacre to silence working class dissent led to the foundation of the modern police force, intended to deliver non-lethal violence against unrest (Farrell, 1992). While perhaps their murder rate is lower than the yeomanry or the parachute regiment, the police have not kept their violence below lethal levels, as witnessed by

The left and labour movement has always been the subject of state repression. The failure of the Peterloo massacre to silence working class dissent led to the foundation of the modern police force, intended to deliver non-lethal violence against unrest (Farrell, 1992). While perhaps their murder rate is lower than the yeomanry or the parachute regiment, the police have not kept their violence below lethal levels, as witnessed by

Some 1,056 delegates to the Democratic Socialists of America convention, representing some 55,000 DSA members, met in Atlanta over the weekend and voted to adopt a series of resolutions that will continue to build a strong national organization capable of carrying out ambitious campaigns in labor and community organizing as well as electoral politics. The central division in the convention, largely driven by rival caucuses and fought out over a number of resolutions, was between those who wanted a stronger central organization capable of organizing strategic national campaigns and those who wanted a more decentralized organization that would encourage local organizing initiatives.

Some 1,056 delegates to the Democratic Socialists of America convention, representing some 55,000 DSA members, met in Atlanta over the weekend and voted to adopt a series of resolutions that will continue to build a strong national organization capable of carrying out ambitious campaigns in labor and community organizing as well as electoral politics. The central division in the convention, largely driven by rival caucuses and fought out over a number of resolutions, was between those who wanted a stronger central organization capable of organizing strategic national campaigns and those who wanted a more decentralized organization that would encourage local organizing initiatives.

“The problem with Americans is they think something is better than nothing.”

“The problem with Americans is they think something is better than nothing.”

The debate over socialist strategy that kicked off with Bernie Sanders’ 2016 campaign has now been going on for almost four years. Over that time parties to this debate have delved deeper into the history of socialism and Marxism in search of analogies and justifications to support their positions. Earlier this year there was an important discussion concerning the political legacy of Karl Kautsky on Jacobin involving James Muldoon,

The debate over socialist strategy that kicked off with Bernie Sanders’ 2016 campaign has now been going on for almost four years. Over that time parties to this debate have delved deeper into the history of socialism and Marxism in search of analogies and justifications to support their positions. Earlier this year there was an important discussion concerning the political legacy of Karl Kautsky on Jacobin involving James Muldoon,

It’s easy to be pessimistic. Since 1979 the key industrial battles have all been lost by the left, resulting in the imposition of the economic settlement we now groan under. And while it looked like social liberalism was all-conquering and irreversible, the appointment of Boris Johnson, the

It’s easy to be pessimistic. Since 1979 the key industrial battles have all been lost by the left, resulting in the imposition of the economic settlement we now groan under. And while it looked like social liberalism was all-conquering and irreversible, the appointment of Boris Johnson, the

Throughout the mid-20th century, discussions and theoretical debates concerning the nature of the capitalist state persisted within Marxist circles. Some names are tightly connected with these events, including Ralph Miliband, Nicos Poulantzas, and Fred Block. In the end, it appeared that a focus on the structural power of capitalism and its proponents won out, with its emphasis on the limitations that capitalism places on the policy decisions of lawmakers.

Throughout the mid-20th century, discussions and theoretical debates concerning the nature of the capitalist state persisted within Marxist circles. Some names are tightly connected with these events, including Ralph Miliband, Nicos Poulantzas, and Fred Block. In the end, it appeared that a focus on the structural power of capitalism and its proponents won out, with its emphasis on the limitations that capitalism places on the policy decisions of lawmakers.

Comrades, students and youth of Hong Kong and Mainland China:

Comrades, students and youth of Hong Kong and Mainland China:

“What Revolutionary Socialism Means to Me” by Sam Farber (on the Jacobin site) is a

“What Revolutionary Socialism Means to Me” by Sam Farber (on the Jacobin site) is a

Neither a policy paper nor a career guide, Gary Roth’s The Educated Underclass: Students and the Promise of Social Mobility (

Neither a policy paper nor a career guide, Gary Roth’s The Educated Underclass: Students and the Promise of Social Mobility (

We express our solidarity with the people of Puerto Rico in their struggle against the corrupt government of Governor Ricardo Rosselló. This Friday marks seven days of massive protests demanding the resignation of the governor and his followers. In spite of attacks with tear gas, rubber bullets and assaults and arrests by police these protests have grown in the capital San Juan and in all corners of the island. On Wednesday, July 17th more than 350 thousand people marched through the streets of the capital, a demonstration without precedent.

We express our solidarity with the people of Puerto Rico in their struggle against the corrupt government of Governor Ricardo Rosselló. This Friday marks seven days of massive protests demanding the resignation of the governor and his followers. In spite of attacks with tear gas, rubber bullets and assaults and arrests by police these protests have grown in the capital San Juan and in all corners of the island. On Wednesday, July 17th more than 350 thousand people marched through the streets of the capital, a demonstration without precedent.

Few films portray working people realistically. One thinks of rare movies such as Hollywood’s Norma Rae, the independent Salt of the Earth, Sergei Eisenstein’s Strike or the Italian classic, The Organizer. These films portray struggle mixed with joy, no matter the success or failure of the plotline. So the screening of At War, set to debut in New York at

Few films portray working people realistically. One thinks of rare movies such as Hollywood’s Norma Rae, the independent Salt of the Earth, Sergei Eisenstein’s Strike or the Italian classic, The Organizer. These films portray struggle mixed with joy, no matter the success or failure of the plotline. So the screening of At War, set to debut in New York at

I can only outline here the complex history of the Nicaraguan revolution and counter-revolution, but cannot do them justice in a short article. I have given a more detailed account in my article “Daniel Ortega, Nicaragua’s Nov. 6 Election, and the Betrayal of a Revolution,”

I can only outline here the complex history of the Nicaraguan revolution and counter-revolution, but cannot do them justice in a short article. I have given a more detailed account in my article “Daniel Ortega, Nicaragua’s Nov. 6 Election, and the Betrayal of a Revolution,”

P

P

Some months ago,

Some months ago,