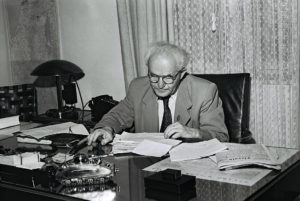

David Ben-Gurion (1886–1973) was a key figure in the creation and building of the State of Israel, second in importance only to the founder of modern Zionism, Theodore Herzl, and central to the establishment of Zionism as the hegemonic politics and ideology of Jews everywhere. He was Israel’s first prime minister from its foundation in 1948 until he retired from political life in 1963 (with a brief hiatus from 1953 to 1955.)The Ben-Gurion that emerges from Tom Segev’s A State at Any Cost is a single-minded figure obsessively dedicated to the creation of the Jewish State in Palestine. He was not, Segev notes, a man of ideas interested in the development of Zionist theory, but a ruthless political and organization man willing to risk everything to accomplish his state-building goal.

He pursued this even if it meant sacrificing the lives of Jews, let alone those of the Palestinians. Segev cites him telling members of his MAPAI party in the late thirties: “If I knew that it was possible to save all the [Jewish] children in Germany by transporting them to England, but only half by transporting them to Palestine, I would choose the second.”

Richly and comprehensively portrayed by Tom Segev, one of the “new historians” challenging Israel’s founding myths, this new biography of David Ben-Gurion presents the history of Zionism and the shaping of the state of Israel through the life and times of its most important founder and political leader. Segev’s critical biography exposes many of the most fundamental problems of Zionism from its beginning. The foundation of the Zionist state is tied up with Ben-Gurion; through examining his life, we see in stark relief how the creation of Israel was from its beginnings incompatible with the creation of a democratic binational state composed of Jews and Palestinians, and the project of Israeli state-building was always doomed to turn Israel into an oppressor nation.

Ben-Gurion’s Zionist Politics and Practice

According to Segev, Ben-Gurion (born David Yosef Gruen) was a Zionist since childhood. Born in Plonsk, a Polish town of 8,000 people with a strong Jewish presence, he grew up in a Jewish middle-class family. His father, a self-employed legal aide, was an early activist in the budding Zionist movement in Poland.

Ben-Gurion left for Palestine in 1906 at age twenty, but unwilling to devote himself to working the land, he left. First, to study at the University of Istanbul — although he never acquired a university degree there or anywhere else, a source of a profound sense of personal inferiority throughout his life — periodically visiting Poland, and then ending, with the onset of World War I, in the United States. Always and everywhere, he was involved in political organization work on behalf of the creation of the Jewish State, and he finally settled in Palestine in the early 1920s where he emerged as a preeminent leader of the Histadrut, a Zionist union that would also become a huge Zionist economic enterprise.

Within the Zionist context, Segev writes, Ben-Gurion considered himself a socialist of sorts, in the sense of aiming to construct a welfare state that assured a minimum standard of living for Jews. Like many of his Jewish contemporaries, he had been impacted by the Russian Revolution. Segev describes him as referring often to his attendance at the sixth anniversary of the Russian Revolution celebrated in Moscow’s Red Square on November 7, 1923 as a representative of the Histadrut.

Echoing the revolutionaries in early twentieth-century Russia who thought the Russian bourgeoisie unable to lead in the struggle to overthrow tsarism and establish a democratic republic, Ben-Gurion’s socialism held, along with many Zionist pioneers, that the Jewish bourgeoisie, driven by their individual, private interests, could not be trusted to build the strong Jewish state he was pursuing in Palestine. However, as Zeev Sternhell argues in his Founding Myths of Israel, Ben-Gurion was most of all a nationalist for whom socialism was a strategy for mobilization and nation-building. His admiration for Lenin did not stem from a substantive revolutionary politics but rather from his determination and iron will in pursuit of his political goals. (He also admired Churchill.)

As a committed “centrist” in the Zionist movement, Ben-Gurion ruthlessly fought against the Bund, the secular Jewish socialist labor movement, while in Poland, and against Communists and left-wing Zionists as well as against Jabotinsky’s and Begin’s right-wing Revisionists in Palestine. And he fought them, writes Segev, as the relentless ferocious political operator he was, ready to eliminate whoever he considered politically undesirable, leading Segev to brand him a “non-Communist Zionist Bolshevik.”

Ben-Gurion was combatively intolerant of disagreement with his own political associates, sometimes out of calculation and sometimes due to the loss of his self-control. “His manner of speech is simply inhuman.” Segev cites Moshe Sharett, a one-time Israeli prime minister and leading member of Ben-Gurion’s government, “If you agree with him eighty percent and differ twenty percent, or agree with his main point and argue a minor part, or agree in general but differ on a specific detail — he immediately focuses all his fervor on that twenty percent, that minor point, or that detail, and the altercation is so powerful that it is as if the dispute were over one hundred percent.” Sharett added that “you never manage to get out a complete sentence with him. He immediately interrupts, latches onto a word he doesn’t like, confronts and rages.”

Like all Zionists, Ben-Gurion’s Zionism was premised on the belief that antisemitism was a permanent and inevitable feature of the human condition, and that the only solution to this problem was to create a Jewish State in Palestine. He held on to this conception throughout his life, allowing only for one exemption: the United States. It is worth noting, though Segev does not explore this issue, that Ben-Gurion held on to this view — notwithstanding the fact that especially before World War II, antisemitism was rife within the United States.

And when American antisemitism substantially diminished after the end of the war, Ben-Gurion seems to have also ignored that fact, which would have forced him to consider the role that the postwar changes in the socioeconomic conditions of the American Jewry played in it. His disregard for these historically bound conditions was consistent with his Zionist view of antisemitism as an inevitable part of the human condition.

What Segev does note, however, is that for Ben-Gurion, as it had been for Herzl, antisemitism was perversely a great ally to Zionism, with every manifestation of antisemitism becoming a “boost” to Zionism. This did not mean that Zionist leaders actively encouraged antisemitism, but it did mean a certain degree of resignation to it as inevitable and a repeated willingness to make deals with antisemites, if Ben-Gurion and other Zionist leaders saw it as beneficial to the Zionist project.

As the hard Zionist he was, Ben-Gurion stood for the territorial expansion of a Jewish state. At the 1937 Zionist congress in Zurich, he declared that “our right to Palestine, all of it, is unassailable and eternal” and that he was “an enthusiastic advocate of a Jewish state within the historical boundaries of the Land of Israel.” Thus, as Segev notes, the proposal for the territorial extension of Israel beyond the Green Line (demarcating Israel’s boundaries before the 1967 War) was not the monopoly of the right-wing Revisionists, but was shared by both “right” and “left” Zionists, Ben-Gurion included. Thus, Ben-Gurion’s reputation as a “liberal” Zionist rests on his greater pragmatism than the more hawkish right wing led by Jabotinsky and Begin, the welfare state created under his rule, and his secularism, which however did not prevent him from making major concessions to the religious Jews at a time when they were far weaker than today.

Regarding Ben-Gurion’s expansionist views, Segev presents a detailed narrative of how in 1954, under the rule of Ben-Gurion’s Mapai (an earlier version of the Labor Party), the IDF General Staff’s Planning Department produced a study titled “Nevo,” upholding the need to expand Israel’s Green Line borders for various economic, social, and demographic reasons and presenting several alternatives for such expansion. The most ambitious proposal involved setting back Egypt’s border to the far end of the Sinai Desert, preferably on the bank of the Suez Canal; taking parts of Saudi Arabia in the South, and if possible allow Israel to control the Arabian oil fields; taking over Syrian lands; and setting the border with Jordan far east of the Jordan River, a proposal which, incidentally, would have covered a territory substantially larger than the one currently controlled by Israel.

Thus, “Nevo” demonstrates that while Israeli governments always attempted, with varying degrees of success, to justify territorial expansion in the context of grave moments of crisis, such plans had been prepared by the Isareli government long before the crises erupted.

No Future for Coexistence

At the same time, Segev notes, Ben-Gurion was a tough-minded realist well aware that, like the Zionist Jews, the Palestinians wanted their nation in Palestine too, and that they would not simply fold their hands and agree to give up their land to the Jews. From Ben-Gurion’s point of view, there could be no future for Arab-Israeli coexistence within the same territory. So, his plans sought to expand Israeli territory into areas populated by a minimum of Arabs in it.

This explains his initial opposition to Israel going to war in 1967, because it would mean ruling over lands entirely populated by Arabs and what he knew would be Arab hostility to the Zionist project. But as Segev indicates, Ben-Gurion was soon “swept up by that ecstasy produced by the victory and conquests” and began to advocate a clearly expansionist program, particularly when it argued for Israeli control of the Gaza Strip with its inhabitants being moved to the West Bank with Israeli assistance and supposedly with their consent, and negotiations with inhabitants of the West Bank to establish an autonomous entity tied to Israel economically, with an outlet to the sea through Israeli ports although with the presence of Israeli troops to “guarantee the West Bank’s independence from Jordan.”

His same notion of minimizing the Arab Palestinian presence also explains the central role he played, according to Segev, in the expulsion of Palestinian Arabs from their land in the 1948 war. It was the work of Segev and other Israeli “new historians” that exploded the Zionist myth, although Palestinians were of course already well aware of it, that on the eve of the declaration of the state of Israel Palestinian Arabs, had abandoned their homes, towns, and villages of their own free will heeding the calls and exhortations of their leaders.

In fact, as Segev has shown, most Palestinians were forcefully expelled by the Haganah (Jewish Israeli Army) or ran away terrorized and in fear for their lives due to the threats and actions of the Jewish forces. That included, in Segev’s long and detailed list of examples, the Palestinian neighborhoods in the lower part of the city of Haifa, where the Haganah “was bombarding them from the upper slope of Mount Carmel with mortar fire.” It also included the forceful expulsion by the Israeli Army of the Palestinians from their conquered town of Lod; the expulsion of Palestinians from the Christian village of Iqrit.

Segev shows that Ben-Gurion generally approved these actions, and that he also insisted, during a truce in the 1948 war, on restarting the hostilities as an opportunity to “clean” the Galilee of the 100,000 Palestinians who had sought refuge there.

In spite of its tendency to altogether avoid dealing with the existence of the Palestinians in Palestine, the Zionist movement had on occasion discussed the possibility of removing or “transferring” them out of the boundaries of the Jewish state. As early as June 1895, Herzl, in line with his diplomatic and “realpolitik” outlook, had come out in support of transferring, “discreetly and circumspectly,” the Arabs out of Palestine. Zionist leaders such as Aharon Zizling advocated in 1937 a transfer based on a “real population exchange” of Palestinians for the Jews of Iraq and other Arab countries.

Such proposals never considered why Palestinian Arabs would want or need to leave their land, even voluntarily. Prominent Zionist figures like Golda Meir and Berl Katznelson did not object in principle to the transfer notion but considered it unfeasible.

Whether Zionist leaders considered the transfer of Arabs practical or not, few considered the possibility of its leading to an Israeli-style apartheid system that we see today in Israel-Palestine. One exception was Zionist leader Menachem Ussishkin who in 1941 explicitly argued that any attempt to create a Jewish state before there was a Jewish majority in Palestine would result in a Zionist apartheid.

Pointing out that in South Africa whites were only 20 percent of the population and that the remaining 80 percent were blacks who had no rights at all, he questioned whether the Zionist movement should stand for having the Jewish 20 percent of the total population ruling the whole of Palestine. He confronted Ben-Gurion’s call for the creation of a Jewish state as the first priority, and conferring equal rights to the Arabs, and transferring those voluntarily agreeing to it, arguing it was contradictory and unrealistic. As he put it, “it is impossible.”

Ussishkin insisted that Zionist goals in the proximate future had to focus on large-scale Jewish immigration to Palestine instead of creating the Jewish state (Ussishkin was so fixated in avoiding the possibility of a South African–type apartheid system in Palestine that he never considered his own proposal could have led to an oppressor Zionist state close to the US model of white/black and particularly white / Native American power relations.)

Segev also documents how Ben-Gurion’s Zionism clearly and unambiguously precluded any possibility of turning Israel into a binational state, a free and independent state of Palestine/Israel or of Israel/Palestine, based on the coexistence of two equal peoples, with national and cultural rights and autonomy safeguarded for both. As in the case of the multinational state of Canada (comprising the indigenous nations, immigrants of various national origins, and the far more numerous French- and English-speaking Canadians), such a state would require a long process of struggle to ensure that the rights of the oppressed national groups are vindicated in deed as well as in the laws of the country.

Ben-Gurion concentrated his vitriol on the German Jewish liberals who supported binationalism, such as Martin Buber, whom he attacked by questioning his loyalty to Judaism and accusing him of having the psychology of a servant. Branding binationalism as treasonous, Ben-Gurion warned its advocates that by reaching “an agreement with the Arabs, you will be in Hitler’s camp.”

The binationalist proposals were intended to create a bridge to the Palestinian Arabs violently resisting a Zionist emigration to Palestine characterized, among other things, by the Jewish settlers’ poor treatment of Arab labor, the purchase of land that led to the ejection of Arab tenant farmers from their land (who Segev claims sometimes were paid compensation and sometimes not), the marginalization if not exclusion of Arab labor from the labor market in agriculture and industry through Zionist labor policies seeking to hire Jewish labor only, and the barring of those Arabs able to get work from joining the Histadrut, the Israeli labor federation, until 1959, and from voting in its elections until several years later.

To combat the Palestinian Arab resistance, Ben-Gurion had been advocating since the 1930s a policy of “aggressive self-defense” that included driving Arabs out of Palestine. Although at some point, in his position as defense minister, which he held simultaneously with his being prime minister, he stated that in pursuit of the goal of peace, the Israeli government had to “gain the hearts of the Arabs.” But he insisted that “there is only one way that we can teach them to respect us. If we don’t blow up Cairo, they will think that they can blow up Tel Aviv.”

Ben-Gurion’s Pragmatism

However, when it came to dealing with international forces, Ben-Gurion’s tough, uncompromising Zionist stance morphed into a totally pragmatic, nonconfrontational position aimed at wresting and negotiating whatever he could from the powers that be. It was this pragmatism, writes Segev, which led Ben-Gurion to take the long view and accept the relatively small piece of land that the United Nations had assigned to Israel in the 1947 Partition Plan.

From Ben-Gurion’s perspective, this was the “half a loaf” that could be made to rise and grow as future circumstances allowed. Thus, when Israel’s “Declaration of Independence” was drafted in 1948, he insisted and prevailed by a vote to five to four in the committee preparing the statement that the Declaration omit any reference to the country’s borders thus leaving the possibility of future expansion open without having to confront major foreign powers and international opinion.

His tactics worked: when in 1948 Israel conquered and annexed a much larger territory than what the United Nations had originally granted to the new Jewish state, the international powers accepted that expansion as an outcome of war — something they would not have been able to do so easily had Israel announced explicitly and in advance its expansionist intentions.

Ben-Gurion, observes Segev, kept his ear to the ground and followed very closely the international relations of forces, especially those involving Washington. He ended up paying a high price in those occasions when he mistakenly ignored or downplayed the pressures coming from those powers, as in 1956, when the Eisenhower administration forced Israel and its senior partners England and France to beat a retreat from their military adventure against Egypt to punish Nasser for nationalizing the Suez Canal.

His pragmatism explains much of the hypocritical dissembling he showed when questioned about delicate political issues that could cost international support for Zionism. At a dinner with Supreme Court Justice Felix Frankfurter and the American diplomat William Bullitt, he piously responded to the diplomat’s 1942 proposal to expel all Arabs from Palestine in order to establish a Jewish state that there was no need to deport the Arabs, because Palestine was economically capable of supporting both Arabs and Jews.

While Segev does not elaborate on this exchange, Ben-Gurion must have known that to have publicly agreed to a plan to expel Arabs from Palestine in 1942 would have been a political and public relations disaster. It was precisely this cautious, diplomatic, and even virtuous discourse that characterized mainstream Zionist pronouncements for foreign consumption, particularly before the foundation of Israel and during the early years of its existence.

That is also what I believe motivated Ben-Gurion’s response, in 1931, to the small group of well-known professionals and intellectuals of Brit Shalom advocating for a binational state and critical of Ben-Gurion’s policies aimed at creating a Jewish majority, emphasizing his supposed concern about the Palestinians: “according to my moral outlook, we do not have the right to discriminate against even one Arab child, even if such discrimination would obtain for us all that we seek.”

Racial and Ethnic Horizons of Ben-Gurion’s European Zionism

Situated in a European context that regarded the Palestinian Arabs as socially and culturally alien, Zionist thought not only avoided discussing them, but even tended to negate their existence by talking about Palestine as an empty land, along the lines of Israel Zangwill’s 1901 motto “Palestine is a country without a people and the Jews are a people without a country,” an example of what social psychologist Leon Festinger called “cognitive dissonance” (an attempt to seek internal consistency by negating or distorting a reality that may create dissonance).

Far from trying to integrate itself in the Arab world, the Jewish state, according to Theodor Herzl, the founder of Zionism, was to be “a rampart of Europe against Asia, an outpost of civilization as opposed to barbarism.” As Segev describes it, Ben-Gurion fully shared in Herzel’s racially charged Orientalism. The 1929 Arab revolt that, according to official figures, resulted in the death of 130 Jews and 100 Arabs, and in over 200 Arabs and 300 Jews wounded, reinforced his Orientalist tendencies leading him to state that the Arabs were “primitive” and that the Jews were facing “an outbreak of the worst instincts of savage masses — inflamed religious extremism, a compulsion for robbery and looting, and a thirst for blood.” For the Arab “son of the desert” looking at the Jew from his “shack,” warned Ben-Gurion, “even the Jews’ barn looked to him like a royal mansion.”

Ben-Gurion looked at the Oriental Jews through the same Orientalist, Eurocentric lens. His reaction to the 1959 riots of the Jews in Israel that had earlier arrived from Arab countries was not very different from his reaction to the Arab revolt of 1929. In a letter to the chairman of the commission of enquiry set up to investigate the events, he wrote “an Ashkenazi thug, thief, pimp or murderer would not be able to gain the sympathy of the Ashkenazi community (if there is indeed such a community), nor would such an idea come into his head. But in a primitive community [such as that of the Mizrahi or Oriental Jews] it can happen.” A few days later, he privately repeated his concern with the growing influence that the Jews from the Islamic world were having on Israeli society.

Like his view of antisemitism as an inherent part of the human condition, Ben-Gurion’s Orientalism made him view economic and sociocultural characteristics of ethnic and racial groups as stemming from their own “nature” instead of stemming from historically caused socioeconomic conditions. That is why he not only regarded as foreign and alien the poor, uneducated, immigrant Jews from the Arab world, but also the destitute and brutalized Holocaust survivors arriving in Israel. They were Jews, Ben-Gurion affirmed, “only in the sense that they were not non-Jews.”

In fact, Ben-Gurion had a Social Darwinist approach to European Jews, only a minority of whom were Zionists during the years preceding the Holocaust. Ben-Gurion made it clear that if it came to choosing between ten thousand Jews who would be beneficial to Palestine and the “rebirth” of Israel and a million Jews who would be a burden, the ten thousand should be saved. As Segev points out, Ben-Gurion conducted the rescue plans “as a realist of narrow horizons and little faith,” adding that the Zionist leader saw the awful significance of the Nazi slaughter not in terms of the enormous number of Jews who were massacred, but instead because that select part of the nation that alone was capable and equipped to build the state had been exterminated.

From Settlers to Oppressor Nation

In the end, Ben-Gurion did succeed in realizing his lifelong goal of creating a Zionist state based both on the exclusion and expulsion of Palestinian Arabs, and on the success of the international Zionist movement he led.

It is impossible to overstate the political hegemony that Zionism achieved over world Jewry in the wake of the Holocaust. It emerged from the political field where it had competed with other political ideologies in the pre-WWII Jewish Europe — principally Bundism and the religious parties — as the unchallengeable political “answer” to antisemitism, and reached its peak with the 1967 war, after which it became the pervasive ideology, politically and culturally, of world Jewry.

Of course, the great majority of Jews, especially in the United States, did not seriously consider emigrating to Israel. But chronic East European Jewish pessimism that often expressed itself as “insurance policy” Zionism (the idea essentially being “it is good to have Israel in case there is trouble and we have a place to go”) had substantial support among Jews outside the United States and Canada. In the 1940s and 1950s, most of the international left also supported Zionism and paid little if any attention to the fate of Palestinian Arabs.

The Bundist and other socialist perspectives that in certain periods such as the late 1930s had been the dominant political tendency of the Jewish community in Poland were thoroughly defeated by the tragic fate of the East European Jews, which dealt a crushing blow to Bundism and more generally to non-Zionist socialism for their position of staying and fighting for one’s rights wherever one lived instead of leaving. The Nazi ideology and its extermination practice won that political battle for Zionism, which could then turn and tell the Bundists and other Jewish internationalists “We told you so.” Political defeats have consequences, particularly for the Bund, whose social base had been wiped out by the Nazis, and to a lesser extent for the religious political parties.

And in fact, the Jewish community in Palestine, and later the Jewish state established by the triumphant Zionist movement led by Ben-Gurion, succeeded in creating a nation, Israel. It was a Jewish nation forged on the basis of a modernized Hebrew language that united Jews coming from many different parts of the world, the effective and thorough socialization of the Israeli Jews into Zionist values, the almost universal participation of Jewish women and men in the IDF (Israel Defense Forces), and a sense of national superiority resulting from the several victorious clashes with the Palestinian and Arab enemies. These forces proved far stronger than the many that could have pulled apart Jews of widely different origins, cultures, and history, in addition to their class differences and ethnic and racial divisions. This was an entirely new Jewish nation. With the exception of the Yiddish-speaking Jews within the Pale of Settlement in the tsarist empire, Jews throughout the world had never constituted a nation before.

The Process of Building an Oppressor Nation

This reality and consciousness of nationhood developed in the course of a historic process that began with the first three (and especially the second and third) waves of ideologically driven settlers who, although relatively small in number, became the intellectual and political leaders of the Yishuv (the Jewish community in Palestine before the Israeli state was created in 1948), and later the state of Israel as it grew substantially through the influx of large numbers of Jewish immigrants and refugees. Only a minority of the latter could be properly considered settlers when they arrived in Palestine, either in ideological or sociological terms. But the great majority of this mass of Jewish immigrants and refugees sooner or later adopted the settler political ideology and followed the leadership of the founding settlers.

But it is important to recognize that, in contrast with the first three migratory waves, they arrived in Palestine (and then Israel) because they had nowhere else to go, not because of the settler-colonial ideological pull that distinguished the previous immigration. This newly formed nation, with its systematic oppression of Palestinian Arabs, became an oppressor nation, very much along the lines followed by the United States in its subordination of its Native American, African American and — after 1848 — Mexican population. The main difference is that the oppressed Palestinians have been better able to place into doubt the legitimacy of Zionist domination than were the Native Americans, black slaves and their oppressed descendants, and the conquered Mexicans with respect to white Anglo-Saxon domination in the North American continent.

Among the most important reasons for this difference has been the Palestinians’ existence within the broad Arab world, which has been the source of large-scale popular support for the Palestinians (as well as betrayals by the Arab ruling classes and government leaders), the Palestinian leaders’ limited but real success in using the Cold War to place their cause in the world’s agenda, and the foundation of Israel with United States and Western support (and also Soviet support in its first few years) in the postwar period as the colonial revolution opposing Western dominance, and its sympathy for the Palestinian cause, was rapidly rising in the Middle East, Asia, and Africa.

As Ben-Gurion himself recognized, by the turn of the twentieth century, only a minority of Jews in Poland and Eastern Europe considered themselves Zionists. Only a tiny minority of East European Jews, who then constituted by far the largest Jewish population in the world, had immigrated to Palestine by the early 1920s. As Zachary Lockman points out in his Comrades and Enemies: Arab and Jewish Workers in Palestine 1906–1948, of the approximately 2.4 million Jews who left tsarist Russia and Eastern Europe between 1881 and 1914, 85 percent went to the United States, 12 percent went to other Western Hemisphere countries (mostly Canada and Argentina) to Western Europe and to South Africa. Less than 3 percent went to Palestine, and for a high proportion of these, it was a temporary stop on their road westward.

The Zionist movement — and it was a social and political movement with a differentiated left, right, and center, notwithstanding the top-down political orientation of the main Zionist leaders like Theodore Herzl to engage the ruling imperial powers in deal-making to achieve their nationalist goals — organized several migratory waves of Jews to Palestine, called aliyot (the plural of aliya, “ascend” in Hebrew, and also “pilgrimage,” according to the Jewish religious tradition commanding Jews to visit the Temple in Jerusalem three times a year). The First Aliyah took place between 1881 and 1903, consisting of some 25,000 to 35,000 Jews from Eastern Europe and Yemen.

As scholars Gershon Shafir in his book Land, Labor and the Origin of the Israeli-Palestinian Conflict, 1882–1914 and Yoav Peled and Horit Herman Peled in The Religionization of Israeli Society have pointed out, the goal of this First Aliyah was to settle the land through privately owned, self-sustaining farms that hired experienced and cheap Palestinian agricultural labor. But this model failed because, at the time, the Zionist movement did not have the financial resources to acquire land for the newly arriving settlers, especially as the price of land skyrocketed due to Zionist demand, and because even the land already owned by the Zionists could have been legally sold to non-Jews.

The Second Aliyah took place between 1904 and 1914, with some 35,000 Eastern European Jews organizing collectives — the kibutz and the moshav — to work the land. Many of them left the land; according to Gershon Shafir, only around 10,000 of those Second Aliyah immigrants remained as agricultural workers. Yet this Aliyah left an important historical legacy by providing the elements of a solution to the quandary faced by the First Aliyah based on the notion of self-employing cooperative settlements on non-alienable, nationally owned land financed by public funds.

It was this new approach that also led to the “conquest of land” from the Palestinians, their exclusion from Jewish-owned and -controlled land. It also established the foundation for the “conquest of Jewish labor,” which minimized and downgraded when it could not totally eliminate the participation of Palestinians in the economy at large, a situation similar to the treatment of Native Americans in the United States. Such “conquests” were the source of the many ensuing frictions, conflicts, and hostilities it produced with Palestinians, a process that has been laid out in great detail in the earlier cited work by Zachary Lockman.

The Third Aliyah took place between 1919 and 1923, with some 40,000 Jews who settled the land following the collectivist approach of the Second Aliyah. This took place at a time when the Zionist leadership, encouraged by the United Kingdom’s Balfour Declaration in 1917, was much more committed to the purchase of land and settlement activity in Palestine, which made it possible for the overwhelming majority of the participants of the Third Aliyah to stay in the agricultural colonies and in Palestine.

These first three Aliyahs fit the classical model of settler colonies, with numerous difficulties mostly deriving from the urban background of the immigrants and the higher standard of living they had had in the countries of origin compared to the local Palestinian population in the predominant rural areas. It was from the Second and Third Aliyot that the main leaders of the Yishuv and later of the State of Israel came, like Ben-Gurion, who came in the Second Aliyah, and Golda Meier, who came with the Third Aliyah. They shaped the principal institutions of the budding nation.

Those three first aliyot were ideological: they were the result of a conscious choice to “solve” the “Jewish problem” of antisemitism in Europe by immigrating and settling in Palestine at a time when other alternatives existed, like emigrating to the United States – which was possible until the 1921 and 1924 legislation that sharply restricted immigration from Eastern Europe — or staying and fighting antisemitism in Europe itself by joining socialist organizations such as the Jewish Bund. The choice to settle in Palestine included Zionists who considered themselves socialists but who, in contrast with the Bund, decided not take on the fight for socialist society in Europe that would grant Jews full civil and political rights and cultural and political autonomy in the context of an emancipated Jewish and non-Jewish working class.

The situation of the subsequent so-called aliyot was different. For one thing, most of those later migrations did not involve a majority of ideologically driven settlers. And by the time they took place, the range of migration alternatives had substantively diminished and eventually disappeared, to the point that a very large number of Jewish survivors of World War II in Europe had to be relocated into the Displaced Persons camps after 1945, since no country wanted to allow them in.

From 1924 to 1965, US immigration was regulated by a quota system sharply limiting the number of immigrants from Eastern Europe. Eastern European Jews emigrated to many different countries outside of the United States. Not surprisingly, a substantial number of them — almost 50,000 — also emigrated to Palestine between 1924 and 1925, constituting the Fourth Aliyah, an aliyah of primarily nonideological immigrants rather than of Zionist colonial settlers. The Fifth Aliyah, between 1929 and 1939, had even less in common with the first three aliyot, as it took place in the context of the coming of Nazism to power and the continued closing of the United States to the emigration of Eastern European Jews (or anybody else for that matter).

It was an act of desperation, not ideological or political choice, with 35,000 Jewish refugees arriving in Palestine in 1933 (about three times as many as the previous year), over 45,000 arriving in 1934, and over 65, 000 arriving in 1935, according to Segev. This immigration to Palestine surpassed, for just those three years, the combined numbers of the first three ideological aliyot.

Ben-Gurion was strongly pragmatic, bordering on opportunistic, in the case of the German Jews wanting to leave Nazi Germany. The Yishuv leadership reached the Haavara agreement with the Nazi government in August 1933, allowing Jews to leave for Palestine. This agreement materially benefited Germany since it greatly facilitated the takeover of Jewish commercial and residential property, although German Jewish emigrants were allowed to take some of their property with them. It was also justifiably opposed by large number of Jews, including the right-wing Zionists led by Zeev Jabotinsky, as a violation of the international boycott of Germany. Nevertheless, approximately 60,000 German Jews emigrated to Palestine from 1933 to 1939.

Most important was the immigration to Palestine of the Jewish refugees that survived the Nazi onslaught, be it the several hundred thousand Polish Jews that survived the Holocaust, mostly in the USSR and Soviet-controlled territories, and those that made it to the Displaced Persons camps. For these survivors, it was inconceivable to think of returning to Poland, especially due to the wave of antisemitism and pogroms taking place there, whether during the war as in the case of Jedbwane in 1941 or after the war, as in the cases of Krakow on August 11, 1945, and of Rzeszow and especially Kielce in 1946. There was no other place that wanted them, so arriving in Palestine (or Israel after 1948) may have relieved them.

But as the Zionist leaders themselves knew, based on the reports they must have received from their agents promoting and organizing the emigration to Israel of Jewish refugees in the Displaced Persons camps, the great majority of those refugees would have much rather emigrated to the developed capitalist countries, especially the United States, had they been allowed to do so by the American and Western governments. (According to Segev, from the summer of 1945 to the British evacuation of Palestine in 1948, more than 70,000 of these Jewish refugees set out for Palestine on sixty-five crossings, although how many actually made it to Palestine is unknown as most of them were intercepted and sent to Cyprus. Nevertheless, in the course of 1948 more than 120,000 Jewish immigrants arrived in Palestine.

Ben-Gurion’s negative view of these new immigrants and refugees constituted a great paradox, as he depended on these Jews for the success of his Zionist nationalist enterprise. Without them, and without the Holocaust that they had managed to survive, there would not have been a state of Israel to begin with. Without it, the British 1917 Balfour Declaration promising the establishment of a national home for the Jewish people, would have remained a useless document by an already declining world power. After all, Great Britain had been all too willing to backtrack on the Balfour’s Declaration’s promises, as seen in its 1939 White Paper that sharply restricted Jewish immigration to Palestine.

In terms of the massive emigration of Jews from Arab countries such as Morocco and Yemen of the 1950s, the bulk of it occurred after the establishment and consolidation of the state of Israel. This emigration generally had more to do with the “pull” forces organized by the Israeli state than the “push” factors in the Arab world, such as the anti-Jewish hostility that may have been fanned by Arab nationalist reaction to the Palestinian Nakba.

Lastly, it is important to note that the colonial settler component of Israeli nationhood has been reinforced by the new type of Jewish ideology and practice that developed after the Israeli victory in the 1967 war and its subsequent territorial expansion, particularly in the West Bank. But by the time that came into being, the Israeli nation had already crystallized, following a path not too different from the United States that started with a Puritan settler colony and evolved into a nation state pursuing a racist policy of expulsion of Native Americans.

Zionism Versus Democracy

The continued expansion and consolidation of Israeli rule as an oppressor nation in the West Bank has clearly made the “two-state solution” inoperable. The putative Palestinian state would have to be established in small, discontinuous parts of the West Bank — quite aside from the fact that this Palestinian “state” was never meant to be truly sovereign, since it would have no armed forces of its own and would be supervised by Israel. Last but not least, at present, any agreement with Israel to establish a Palestinian state would not recognize the right of Palestinian refugees to return to what is now Israel if they chose.

The current military control of the West Bank and Gaza has sharpened the perennial contradiction between democracy and Zionism, in Zionism’s efforts to maintain the ethnic and religious definition of Israel and thus to limit the number of Arabs — a desire explicitly manifested by David Ben-Gurion. In light of the practical demise of the two-state solution at the hands of Israel, the Zionist oppressor state by definition cannot accept the only remaining desirable alternative: a fully democratic and secular binational state comprising Green line Israel, the West Bank, and Gaza with full equality for Palestinian Arabs and Jews. Such a state could not be both democratic and Jewish, particularly when Palestinian Arabs are already or will soon become the majority inside that territory.

Such a binational state would recognize the equality of all existing national cultures and, while secular, also recognize the equality of all religions. The binational democratic state would also have a nondiscriminatory immigration policy hopefully giving preference to the victims of persecution, whether these are Arabs or Jews.

Although such a binational and secular democratic state would constitute huge progress from the current situation, it would be plagued by severe problems such as the major differences in economic development and living standards between Arabs and Jews that even the most generous reparations and compensation programs would have difficulty eliminating at least in the short term. Of course, any socialist development in that part of the world would considerably ease such difficulties.

Segev’s biography of David Ben-Gurion elicits a final reflection on the fate of Zionism. The movement that promised to solve the “Jewish Question” did succeed in creating an increasingly undemocratic modern Sparta in close alliance with the strongest imperialist power. But in fact, antisemitism is disturbingly growing again in Europe and the United States, and there is nothing that Israel has done to effectively combat it. In fact, it has even bolstered it as in the case of its government’s open sympathy for Viktor Orbán, the antisemitic leader of Hungary’s government. You cannot build an enlightened and democratic polity for all people under Israeli rule on the basis of the oppression of a Palestinian nation that has been made to pay the price of a Jewish Holocaust for which they bear no responsibility or involvement.

Reposted from Jacobin.

There were no Arab advocates to speak of for a bi-national state when Israel was established. All of the binationalists were on the Jewish side. The Palestinian Arab leadership offered nothing to the Jews living in Palestine. They wanted an Arab state with no provision for Jewish national or cultural rights. Therefore the Zionists could honestly say that a Jewish state was the only alternative to an Arab state. Who could blame the Jews of Palestine for choosing the former over the latter.