The new wave of large-scale popular uprisings across the Middle East, coming less than ten years after those of 2011, challenge journalistic and academic analyses that view them as a set of individual and largely unconnected cases—the Iraqi Intifada, the Egyptian Revolution, the Lebanese protests, and so on—save perhaps some “contagion effect” across the region. Many analyses examine each uprising within a nation-specific, protest life-cycle narrative—that is, each discrete case “begins” with a moment of mass mobilization within national boundaries, evolves along some trajectory, and then “ends” with either success (transition to democracy) or, most often, failure (civil war, counter-revolution). While this framework produces some insights, the focus on the nation-state level—a kind of methodological and epistemological nationalism–obscures other processes, dynamics and explanations that link or distinguish these uprisings across both time and space.[1]

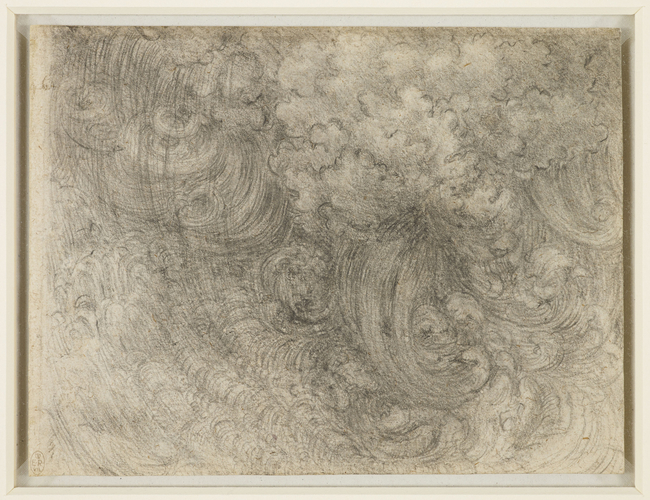

Sudanese holding Algerian and Sudanese flags protest at the Defense Ministry, Khartoum, Sudan, April 17, 2019. Umit Bektas/Reuters

Both the 2011 and 2019 protest waves highlight similar combinations of grievances across diverse geographies, suggesting not only shared regional but also global processes at play. Moreover, these mobilizations occur within a variety of dimensions of the past, present and future not reducible to any pre-determined national lifecycle, and protestors and regimes alike learn from other regional and even global uprisings. The diverse and transformational grievances expressed in these movements also indicates the necessity to go beyond structural determinism or overlooking complex forms of power that include the interweaving of political and economic spheres and to question the epistemological and methodological investments that analysts have and perform in explaining (and sometimes, explaining away) uprisings in the region.

In order to broaden our frameworks for thinking critically about the new round of uprisings, MERIP editorial committee member Jillian Schwedler asked a number of critical scholars for their perspectives on how we should be thinking about regional protests and what is often overlooked or misunderstood. Their responses have been edited and condensed for publication.

John Chalcraft teaches Middle East history and politics at the London School of Economics. He is secretary of the British Society for Middle Eastern Studies.

Since December 2018, mass mobilization has taken place in four countries where it was relatively absent during the Arab uprisings of 2011.[2] In Sudan, mass protests—dubbed the Sudanese Revolution—began on December 19, 2018, and demanded economic reform, the resignation of the long-standing president, representative institutions and an end to military rule. In Algeria, mass protests known as al-hirak, or movement, broke out on February 16, 2019, ten days after an incapacitated president announced his candidacy for a fifth presidential term.[3] In Iraq, the “intifada” began on October 1, 2019 with protests beginning around unemployment, corruption and poor public services; they quickly evolved into demanding the fall of the regime and the end of Iranian intervention into Iraq’s domestic politics. In Lebanon, subaltern and middle-class constituencies went into the streets in large numbers on the night of October 17, 2019. Triggered by a new tax, they began protesting more broadly against economic crisis, the failure of socioeconomic provision, corruption and sectarianism; they are calling for the fall of a ruling class entrenched since the civil war.[4]

Just as in 2011, many have been surprised by these mass protests, and explanations based on standard comparative politics methods seeking to isolate decisive variables based on the country-by-country analysis of sameness and difference have proven difficult to sustain. Many analysts (including myself) had maintained, for instance, that an important reason for the lack of mass political uprisings in Algeria, Iraq, Lebanon, Sudan and Algeria in 2011 had to do with recent histories of civil war, painful memories that deterred those worried about instability and violence from protest. But recent histories of civil war and violence are still present in these four countries, and negative views about the consequences of mass uprising have actually been reinforced in many quarters by civil war and violence in Libya, Syria and Yemen since 2011 and counter-revolution elsewhere.

Similarly, explanations based solely on political economy, social media or globalization can be overly deterministic. While it is undoubtedly true that all of these countries suffer from acute inequality, political corruption, economic crisis and drastic failures in social provision, these features were also present in all four countries in 2011. As for social media, the epoch of internet puffery is surely over: Increased government and security surveillance, use and manipulation of the internet has surely put paid to the idea of the internet as a privileged space of autonomy and freedom undergirding challenges to domination.

If these approaches have limits, the alternative is not a wholesale rejection of generalization in favor of particularism and contingency—the idea that each case is simply unique. We might think instead about alternate critical frameworks of action-embedded understanding. Antonio Gramsci, the communist revolutionary and philosopher of praxis—even as he studied 1917 and the revolutionary protests across Europe from 1918–1920—hewed away from comparative politics and socioeconomic determinism alike. Gramsci’s work, together with the mass uprisings of 2018–2019, confront us with the importance of maintaining a place in our analysis for leadership, historical protagonism and political initiative.

We might think instead about alternate critical frameworks of action-embedded understanding.

Gramsci’s writings on leadership, the crisis of authority, popular explosion, cultural transformation and the dangers in the situation are particularly suggestive. Algeria, Iraq, Lebanon and Sudan present many features of such a crisis of authority, a crisis in the hegemony of the state—for example, in the capacity of the dominant classes to maintain consent in the national social formation. These republics, for different reasons, have certainly failed in major undertakings—to deliver bread, dignity and freedom to their populations over the decades. Vast and diverse masses have become politically active and advanced major demands. But the demands—although revolutionary in their sweeping rejection of the established order, their transgressive mobilization and their many forms of what Gramsci called subversivism—are not organically formulated: They are not yet substantially developed as an alternative form of hegemony, fusing the economic-corporate with the ethico-political and capable of becoming universal nationally or regionally. The result is thus a crisis (of hegemony), an uprising, not a revolution.

Indeed, Gramsci’s concept of a popular or syncretic explosion, replete with anti-government sentiment, has considerable relevance for understanding the current uprisings. Such a syncretic explosion is not in Gramsci spontaneous, except in the sense that it is not under the organizational control of an established actor. Instead, it is a movement whose subaltern leaders are often unknown, the fruit of a much longer preparation. It also comprises repeated experiences of abuse, economic struggle and speechlessness among subaltern populations, as well as the persistent activism of alienated activists and intellectuals.

Even amid effervescence, there are great dangers in the crisis of authority, just as there are in the current uprisings. As Gramsci writes, anti-government sentiment can be fleeting, mass energies can dissipate and the ruling class can re-organize faster and more effectively than first-time protesters, who may lack organization, strategy and mental preparation. The protesters may, as in recent times, put their trust in the military, for instance, or cleave to an abstracted faith in the will of the national people.

Further, Gramsci’s writings weave together different kinds of temporality, reminding us to not confuse a short-term popular explosion with a long-term cultural change. The latter beats to a slower rhythm and involves a protracted cultural and organizational war of position in civil society, the molecular transformation of quantity into quality, the circulation of ideas and the re-working of conceptions of the world more broadly—including among subaltern groups. Gramscian optics suggest that we should pay attention to longer-term temporalities around cultural struggle, the role of organic intellectuals, civil society and subaltern cultural politics in our critical interpretation of these uprisings.

Finally, Gramsci’s embrace of leadership and democratic centralism—as against both spontaneism and vanguardism—and his appreciation of the importance of political society and the state alerts us in the present to the cultural, socioeconomic, political, organizational, and strategic weaknesses of horizontalism—the idea of popular organizing without any leadership. Many of these weaknesses shape the disappointing post-2011 trajectories, as a number of activists have learned.

More insightful than analyses of the uprisings based on cross-national variation or political economy are critical frameworks that eschew mechanical determinism and allow for historical protagonism, understood as transformative activity challenging subordination and hegemony. Such alternative frameworks can grasp processes of revolutionary learning, even across national borders. Protest organization crossing national borders is still only embryonic, and nationalist and statist imaginaries and practices remain all too directive in the insurgent imagination. Nonetheless, these uprisings have involved the transnational social life of ideas, strategies and tactics, a transnationalism which, beyond the methodological nationalism of academics and populist nationalism more generally, has been and could be an ever more significant feature of popular challenges to subordination in the region and beyond.

Adam Hanieh teaches development studies at SOAS, University of London.

I certainly agree that much analysis of the uprisings (and the Middle East in general) is marked by a kind of methodological nationalism, where the borders of the nation-state are assumed to be a natural, pre-given container of social relations. The 2011 uprisings (and those of today), however, not only confirm the striking commonalities that exist across different states in the region but also help highlight the crucial importance of moving beyond such state-centric frameworks to place regional developments within a broader transnational framework of understanding.

The profound cross-border flows of people, capital, ideas and resources mean that many of the social science categories we typically use to describe the region need to be re-considered. How do we fit, for example, the millions of people who have recently been displaced across borders in the Middle East—or the millions more who are temporary migrant workers lacking basic rights of citizenship—into our thinking about labor and working classes in the region? Likewise, does it make sense to speak of a national bourgeoisie (as parts of the Arab Left continue to do) when we see such significant levels of cross-border ownership and investments in the region, and where for many of the region’s largest businesses their national territory is often no longer the main space of their accumulation?

I also think the uprisings have confirmed the close interweaving of the political and economic spheres in a way that runs against the grain of much mainstream policy and theorizing around the Middle East—where free markets are said to promise greater political freedoms and the region’s problem is viewed as simply one of authoritarianism, corruption or nepotism. I think we can now clearly see that there is no essential contradiction between neoliberal economic policies and political authoritarianism—indeed, the opening up of markets and the steady creep of neoliberal policies throughout the region depended precisely upon authoritarian rulers (as it still does). This reliance is not an anomaly globally—indeed, the term authoritarian neoliberalism is increasingly used to describe this twinning of authoritarian and repressive states and free-market capitalism. The supposed authoritarian exceptionalism of the Middle East now seems like an anachronism given these global trends.

In this sense, I think we should understand the uprisings that swept the region throughout 2011 as targeting both the neoliberal economic policies that were so heavily promoted by Western financial institutions over the last few decades as well as the political structures with which they were twinned. Not all uprising participants thought about the protests in this manner, of course, but the demands that emerged through the uprisings—the focus on social justice, wealth inequalities and autocracy—make this fusion of the economic and political spheres quite evident. For these reasons, I think one of the clear lessons of the last decade is the necessity of reversing the extreme disparities in the control and distribution of wealth in the region. It’s not enough to focus solely on political demands such as new elections or governmental corruption without simultaneously addressing the question of socio-economic power. And as John observes, what has been interesting over the last few months is the ways in which key countries that were to a degree outside the protests of 2011 have now seen their own uprisings–Sudan, Algeria, Iraq, Lebanon and Morocco. In all these cases, the interweaving of the political and economic spheres has been an essential driver of the protests.

At the same time, it is important to think about these uprisings (those of today and years past) in a global frame. First, the 2011 uprisings were related to the effects of the 2008–2009 global economic collapse and the ways that this crisis was transmitted throughout the region. Today’s mobilizations are also occurring at a moment when global economic growth has slowed considerably, and many analysts are predicting a re-run of the global crash a decade ago. Second, the protests of 2011 were an integral part of—and helped to shape—other global struggles at the time. I’m not just talking here about the high-profile cases of Occupy, the Indignados in Spain and so on, but also about the less widely acknowledged protests, particularly throughout the African continent. Indeed, an overly restrictive geographical rendering of the 2011 Arab uprisings was the subject of an excellent book edited by Firoze Manji and Sokari Ekine in 2011, which drew attention to the protest movements in Benin, Gabon, Senegal, Swaziland, Ethiopia, Djibouti and Uganda that were contemporaneous with the uprisings in Tunisia and Egypt but largely ignored at the time.[5] Likewise, the Middle East today is part of a wider set of international mobilizations, be it in Chile, Hong Kong, Haiti, Colombia, Ecuador, Spain and elsewhere.

These protests are a global phenomenon, and for this reason, it’s important to situate the current uprisings in the Middle East within the complex transition of the world system that we are currently living through.

These protests are a global phenomenon, and for this reason, it’s important to situate the current uprisings in the Middle East within the complex transition of the world system that we are currently living through. Are we witnessing a relative decline of US power and the rise of new global challengers? If so, what does this mean for the Middle East and popular protest? The attempts by foreign powers to project and protect their influence in the Middle East are yet another confirmation of the strategic significance of the region to global politics.

Closely connected is the struggle for regional hegemony by local powers. My own work has particularly looked at the role of the various Gulf states, which has a political economy dimension related to the outcomes of neoliberal restructuring over the previous period—a process that accentuated the weight of the Gulf throughout many key economic sectors in the region.[6] One of the conspicuous features of the current protests is the prominence of slogans against Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates, something that was much less apparent in 2011. Obviously, we can also see these regional power struggles reflected in the various interventions of Turkey and Iran. In general, I think we need a much better understanding of how these regional and international dynamics intersect. We need to take local struggles seriously and avoid trying to explain everything through geopolitics.

It’s striking how the current protests closely echo the same concerns and demands of the 2011 uprisings. At the same time, I hope the anti-sectarian impulse that seems to be evident in today’s protests (at least for now!) speaks to an internalization of the experiences of the earlier uprisings. And we need to place these waves of protest in much longer time frames—we can’t understand the current moment without looking at the roll-out of neoliberal structural adjustment packages from the 1980s and 1990s, or the disastrous consequences of the decade-long US invasions and blockade of Iraq from 1991 onwards. Indeed, the current protests in Iraq are just as much about the constitutional system foisted on Iraq by the US occupation post-2003, as they are about Iran’s sectarian domination of the current political establishment.

Thinking about diverse time-frames, or temporality, Walter Benjamin spoke of the non-linear and discontinuous moments that occur at moments of rebellion—which recuperate and validate earlier periods of struggle—contrasting this to the kind of homogenous, empty time that we typically experience. He also emphasized the importance of seeing the traces of the past in the present. I’ve always liked these ideas, as they speak to the ways in which the effects of protest and rebellion persist in ways that may not be immediately obvious (even when these movements have been apparently unsuccessful). One of these effects, which I think is often underappreciated in our rush to talk about success or failure at the level of the state, are the profound personal changes that often occur in individuals during their participation in mass political action. People experience a kind of shaking-off of apathy and breaking down of the individualized and competitive ways in which we are accustomed to live our lives—the potential to get a small glimpse of a different future. This experience may only last a short period of time, but these moments live on in how people think and act and can thus help form the ground for future movements.

I agree with John that the work of Gramsci can really help in understanding these processes, particularly his critical assessment of the relationship between consciousness, social movements and political leadership. It has become fashionable in some circles to speak of leaderless movements or to counterpose horizontalism to vanguardism as forms of political organization. Gramsci helps us see that all social movements are about the contention of different leaderships. What matters is the politics of those leaderships and their ability to connect with, learn from and articulate the interests of particular subaltern classes. In this respect, I feel something often obscured in academic work on Gramsci is that his writing was primarily concerned with the category of class—what are the class interests represented in particular movements, which classes have leadership and how is this leadership maintained? As Maya points out, class is key to understanding the current uprisings. Looking at Iraq, for example, where we saw a general strike by oil workers in support of the demonstrations and also strikes by teachers’ unions in the south. In Lebanon, the demands around nationalizing banks similarly help to identify where actual power is held in Lebanese society and how capitalism works in the country.

But Maya is also absolutely right to stress that we can’t think of class simply in economic terms. In any concrete place, as anti-racist Marxist feminists such as Angela Davis have long noted, classes are simultaneously constituted through gender and other relations (including that of race). We need a much better understanding of how this works in the Middle East. It’s no accident that one of the features of the counter-revolution in places such as Egypt has been the violent reassertion of particular gender roles and norms of sexuality.

We also need to recognize the many smaller and less visible protests that have taken place over the last decade. Huge numbers of strikes, protests and other actions across the region barely register in media coverage, such as the recent women’s protests in Palestine. Even as the mass uprisings subsided, protest never disappeared despite war, mass displacement and the apparent restoration of authoritarian rule. When we rush to periodize uprisings we can overlook these continuities of mobilization and organization that are essential to the emergence of large demonstrations such as the ones we see today.

Maya Mikdashi teaches gender studies and Middle East studies at Rutgers University, New Brunswick.

Methodological nationalism and other intellectual blinders manifest themselves in several ways in analyses of the 2011 and 2019 popular, anti-regime uprisings in the Middle East. At the metatheoretical level, there is a particularly Euro-American academic nationalism about its own authoritative role in producing methods and knowledge related to the uprisings. On a different scale, the national frame obscures what Adam elaborates upon—that nation-states in the region are themselves already trans- and multi-national. Finally, these forms of contemporary analysis often privilege particular understandings of political difference and transition that circumscribe our ability to understand not only the content of protestor demands, but also the varied methods protestors are employing, and the knowledge they are producing across the region.

Scholars have devoted considerable attention to whether this or that uprising in the Middle East meets the definition of a revolution. This scholarly debate has not been value-neutral, but rather reveals the investments of the Euro-American academy in its authority to define the terms of the mass protests demanding political, economic and social change. If people are claiming the mantle of a revolution or an uprising, who are we to explain to them (most of the time from far away) why they are wrong?

Moreover, why must uprisings in the region (and in the global south more generally) be measured as successes or failures according to the dominant theoretical and epistemological frameworks in the Euro-American academy? Why not ground new theory or thinking about the meaning of political protest and revolution from the region? After all, our archive for the term “revolution” is partially produced through obscuring and silencing—in Michel Rolph Trouillout’s terms[7]—the enslaved-led Haitian revolution and other historical events that were not led—or theorized—by white men of all classes. The terms we use and the histories we draw on to understand and to measure mass protests in the Middle East are themselves produced through political, methodological, epistemological, economic and ideological power. This power amplifies particular histories as much as it silences others.

The limitations of the nation-state frame of analysis prevents us from recognizing how the 2019 uprisings—from Iran to Hong Kong—are all in some part against global neoliberal austerity and wealth concentration on the one hand, a hyper-connected international political and economic elite who are benefiting from this regime on the other hand, and an increasingly global, digital and highly personalized and efficient security apparatus on yet a third hand. If we take the examples of Iran, Iraq and Lebanon, important differences and similarities emerge. First is the role that the United States and international sanctions play (and did play in Iraq) in the economic crises felt most acutely by ordinary people in Lebanon and Iran. Iran has been in a long-running proxy war with the Saudi-American alliance that manifests in post-US invasion and occupation Iraq and in Lebanon. Both Iran and Iraq have resource-rich economies, while Lebanon is primarily a service-based economy in which the banking sector plays an oversize role.

Both the prime ministers of Iraq and Lebanon have resigned, although these resignations have different effects structurally and politically. The Lebanese state has yet to repress protesters with the scale and intensity of violence we are seeing in Iran and Iraq, partially because protesters themselves have not forced the armed forces to show their hand. In addition, the protests in Iraq and Lebanon share many demands, such as ending corruption, holding political elites accountable and rolling back political sectarianism. In addition, personal status law in both Iraq and Lebanon is an intensifier of sectarianism, with feminist and anti-sectarian protestors in Iraq drawing attention to the dangers of passing separate personal status laws for different religious and sectarian groups.

As John notes, Lebanon, Iraq, Algeria, Sudan and Iran are all post-war countries, and the wars of the past animate the uprisings and embolden them. Protesters acutely feel that they have suffered too much, and for far too long—and that many civil, regional and international interests prefer civil wars or violence to regime change. The Lebanese model was cited as an antecedent to American-imposed political sectarianism in Iraq. This model facilitates corruption, as leaders seek to control access to state services through cultivating sectarian-clientelist networks. It is important to note here that the “Lebanese model” is in fact a French imperial model of rule through difference, recalibrated decades later by American imperial power in Iraq. Comparative or regional analysis must pay close attention to historical difference and similarity, as well as to international and regional articulations of power and rivalry.

As Adam notes, the uprisings’ demands of 2019 are not only resonant with those of the 2011 uprisings: They bear the lessons and warnings of 2011. Protesters in Lebanon, for example, have learned from Egypt the unique threats that the army poses and the ways that sexual violence was weaponized by counter-revolutionary forces. They are likewise wary of the ways in which Syria’s uprising evolved into a protracted civil war marked by heavy foreign intervention. Protesters across the region also share tactical and strategic knowledge, such as how to deal with tear gas, how to effectively occupy public space and how to mobilize and distribute alternative legal, media and medical support.

If the regime in Lebanon is understood as neoliberal, patriarchal and constituted through political sectarianism—the logic and practices that make this regime cohere is what I have called “sextarianism.”

Methodological nationalism obscures not only connections across states but also complex dynamics within them. In Lebanon, unemployment and weak public services and institutions were endemic to post-civil war economic restructuring, which led to the hollowing out of the middle class and its spending power. The class and social interests of the professional and remaining middle- and upper-middle classes are closer to those of the elite than they are to the 30 percent of the country living in poverty. Elite universities and private K-12 schools are both containers and incubators of economic and social segregation. Economic segregation—and the resulting class alignments and polarizations between poor, working, middle and upper classes—has social and political consequences, some of which are beginning to be seen on the ground.

Furthermore, a third of Lebanon’s residents are not Lebanese citizens but migrant workers and refugees from wars in Syria, Iraq, Sudan and Palestine. The oft-repeated statistic that a third or even half of the Lebanese population is in the streets discursively erases a third of the population by not counting migrant workers and refugees as part of the population. In fact, 2019 saw not one but two uprisings in Lebanon. The first was a Palestinian uprising against a xenophobic and punitive labor law and against the conditions of neglect and corruption under which Palestinians live. The second and more widely recognized uprising began months later, in October 2019, and has yet to substantively address non-Lebanese concerns. The nation-state framework works to further obscure revolutionary and mass movements of peoples in the region for self-determination, including Kurdish-led movements that have also been invigorated in the region post-2011.

Life-cycle analysis, as Jillian put it, also limits our temporal understanding of political uprisings and transitions. The October 2019 protests in Lebanon are years in the making: They have important antecedents in the 2011 anti-regime Hirak and the 2015 YouStink Protests. Life-cycle analyses also generate the unwarranted confidence of scholars to declare each uprising either a success or a failure, based primarily on whether there has been regime change at the time of their writing. Yet regime change is not the only measure of whether or not an uprising has been successful, just as structural transition should not be the only measure of the effects of an uprising. An uprising is a temporal order in and of itself, and it causes a temporal break—there is a before and after 2011 Egypt, just as there will be a before and after 2019 in Iraq and Lebanon. Moreover, regimes are not only made of laws, policies, bureaucracies, constitutions and institutions. Regimes are also ideological and affective—they are the logic, relations and practices that course through and define the relationships between a government and a state and a body public.

Thus, if the regime in Lebanon is understood as neoliberal, patriarchal and constituted through political sectarianism—the logic and practices that make this regime cohere is what I have called “sextarianism.”[8] Simply put, sextarianism unpacks how the political technologies of the state articulate sectarian and sexual difference together legally, bureaucratically and ideologically. This co-constitutive nature of sectarian and sexual difference is self-evident to those who have studied the law and bureaucracy of Lebanon, but epistemological and methodological nationalisms and hierarchies are so strong that analysts can at once see and unsee that co-constitution. Political sectarianism is a system built on two poles: 1) Personal status law and the system of census registration to which it is tied, which produce the legal and bureaucratic architecture of separate and measurable “sects,” and 2) a power-sharing agreement between these bureaucratically and legally differentiated sects and citizens. Sects and citizens and sectarian-citizens are not naturally occurring phenomena. We must understand the ways that political difference is structurally reproduced in order to both analyze and mobilize effectively, a point that feminist and legal groups have stressed throughout.

Political sectarianism also has a temporal register—it claims to represent and channel pre-existing and discrete sectarian interests until the population is made ready by the state for liberal democracy. This forever temporary nature of political sectarianism should be understood as securing the liberal, redemptive and pedagogical work of the Lebanese nation-state, as well as its futurity. In short, the forever temporality actively reproduces the future tense of the nation-state precisely because it keeps citizens suspended within the temporality of the temporary, backed by a fear of the tyranny of the majority if political sectarianism is ended before national citizens have been successfully made out of sectarian citizens. According to such logic, political sectarianism should end only when citizens are no longer sectarian.

Thus far, protesters have made gains in putting these two aspects of the regime under stress—its sextarian nature and its temporal order. Protesters are refusing the temporality of the temporary, and they are drawing attention to the ways that sectarian difference is structurally produced through masculinist and patriarchal bureaucracies and policies. These seemingly small achievements stand outside conventional academic notions of structural change, yet they are crucial precisely because they strike at the affective and ideological edifice of the power regime in Lebanon.

In sum, sectarianism, neoliberalism, patriarchal power (authoritarian or not) and corruption are co-travelers in protestors’ minds across the region and should be in the forefront of our analyses as well. Comparative analysis is an invitation to develop new analytics as to how and why political uprisings take shape, and what the culture of neoliberalism has come to be associated with beyond economic and political policy and practice across different locations. The intifadas of 2019, and of 2011 before them, should inspire us to intellectual intifadas that refuse to naturalize the ways that our analysis of power and of uprisings in the Middle East are always already bound to the structural conditions and stakes of producing knowledge about the Middle East in the Euro-American academy.

ENDNOTES

[1] Schwedler develops this critique further in “Comparative Politics and the Arab Uprisings,” Middle East Law and Governance 7/1 (April): 141–152.

[2] Chalcraft analyses the 2011 uprisings in the context of more than a century of resistance in Popular Politics in the Making of the Modern Middle East (Cambridge University Press, 2016).

[3] See Robert P. Parks in this issue.

[4] See Rima Majed and Lana Salman in this issue.

[5] Sokari Ekine and Firoze Manji, eds., African Awakening: The Emerging Revolutions (Pambazuka Press, 2011).

[6] See Hanieh, Money, Markets, and Monarchies: The Gulf Cooperation Council and the Political Economy of the Contemporary Middle East (Cambridge University Press, 2018), winner of the 2019 British International Studies Association International Political Economy Group Book Prize.

[7]Michel-Rolph Trouillot, Silencing the Past: Power and the Production of History (Beacon Press, 1995).

[8] See Mikdashi, “Sextarianism: Notes on the Studying the Lebanese State,” in Amal Ghazal and Jens Hanssen, eds., The Oxford Handbook of Contemporary Middle-Eastern and North African History (Oxford University Press, 2018).

The demographic data collected and reported in the media for sickness and mortality rates due to COVID-19 has focused on age and to a certain extent gender. While mass hardship from unemployment has been widely reported, we have heard little about sickness or mortality rates by class or race for the coronavirus. There is nonetheless, clear evidence that class and race, and health and disease in general are closely linked. It is very likely therefore that sickness, recovery, and mortality rates for the Coronavirus pandemic will closely mirror class divides within countries and between rich and poor countries. Individual and household incomes, which reflects the class structure in a general way will be a key factor in how different classes experience the pandemic and its aftermath. Workers and the poor and people of color will likely suffer at greater rates than more privileged class and racial groups.

The demographic data collected and reported in the media for sickness and mortality rates due to COVID-19 has focused on age and to a certain extent gender. While mass hardship from unemployment has been widely reported, we have heard little about sickness or mortality rates by class or race for the coronavirus. There is nonetheless, clear evidence that class and race, and health and disease in general are closely linked. It is very likely therefore that sickness, recovery, and mortality rates for the Coronavirus pandemic will closely mirror class divides within countries and between rich and poor countries. Individual and household incomes, which reflects the class structure in a general way will be a key factor in how different classes experience the pandemic and its aftermath. Workers and the poor and people of color will likely suffer at greater rates than more privileged class and racial groups.

Grocery aisles stand devoid of toilet paper rolls, paper towels, meat, and canned products as panic-stricken urbanites stock their pantries and garages to avoid multiple trips to the supermarket, or maybe even to avoid doomsday scarcity. When people do visit such stores, they quickly part, skirt, and dart away from each other—social distancing is something we Americans are quite adept at, we have always liked our private spaces, we have always been studious about not encroaching physical and emotional spaces of our fellow humans leaving such “encroaching” behaviors to doctors and shrinks. We have preferred to live in the suburbs where more distant our homes are from our neighbors, the more valuable our property has been. As a civilization, we Americans have associated happiness and well-being with the accumulation of stuff, protection of private property, and the defense of our individuality. President Trump has applauded Americans for doing really well in taking social distancing seriously, and yet, more recently, under pressure from the ruling class, he also announced that America will be open for business soon. For the first time in recent history, the two key concepts of individual liberalism are in conflict with each other: individual freedom clashes with the pursuit of happiness.

Grocery aisles stand devoid of toilet paper rolls, paper towels, meat, and canned products as panic-stricken urbanites stock their pantries and garages to avoid multiple trips to the supermarket, or maybe even to avoid doomsday scarcity. When people do visit such stores, they quickly part, skirt, and dart away from each other—social distancing is something we Americans are quite adept at, we have always liked our private spaces, we have always been studious about not encroaching physical and emotional spaces of our fellow humans leaving such “encroaching” behaviors to doctors and shrinks. We have preferred to live in the suburbs where more distant our homes are from our neighbors, the more valuable our property has been. As a civilization, we Americans have associated happiness and well-being with the accumulation of stuff, protection of private property, and the defense of our individuality. President Trump has applauded Americans for doing really well in taking social distancing seriously, and yet, more recently, under pressure from the ruling class, he also announced that America will be open for business soon. For the first time in recent history, the two key concepts of individual liberalism are in conflict with each other: individual freedom clashes with the pursuit of happiness.

When I first wrote this article on Friday, March 27, the

When I first wrote this article on Friday, March 27, the

After over nine months of negotiations, on March 10, 2020 members of Saint Paul Federation of Educators (SPFE) took to the streets to fight for the schools our students deserve. Then, just one week later, we were back in our classrooms, packing up everything we would need to transition to distance learning, due to COVID-19.

After over nine months of negotiations, on March 10, 2020 members of Saint Paul Federation of Educators (SPFE) took to the streets to fight for the schools our students deserve. Then, just one week later, we were back in our classrooms, packing up everything we would need to transition to distance learning, due to COVID-19.

This article was written for L’Anticapitaliste, the weekly newspaper of the New Anticapitalist Party (NPA) of France.

This article was written for L’Anticapitaliste, the weekly newspaper of the New Anticapitalist Party (NPA) of France.

Although Venezuela is only reporting 153 coronavirus infections and seven Covid-19 deaths as of April 4, that is likely a radical underestimation of the contagion’s spread. Venezuela’s healthcare system has been pushed to the breaking point by years of U.S. sanctions and has meager means for mass testing. The collapse of world oil prices and the decision by Russia’s state oil firm

Although Venezuela is only reporting 153 coronavirus infections and seven Covid-19 deaths as of April 4, that is likely a radical underestimation of the contagion’s spread. Venezuela’s healthcare system has been pushed to the breaking point by years of U.S. sanctions and has meager means for mass testing. The collapse of world oil prices and the decision by Russia’s state oil firm

One of the most astounding statistics to emerge from the escalating coronavirus pandemic is how the death rate from the virus in Germany is markedly lower than other countries.

One of the most astounding statistics to emerge from the escalating coronavirus pandemic is how the death rate from the virus in Germany is markedly lower than other countries.

A newscast on SUR Peru Sunday showed residents of Lima at their windows clapping and thanking the masked sanitation workers loading bags of trash into a garbage truck. The screen read, “Coronavirus: Cleaning in Lima, Anonymous Heroes.” Residents knew whose labor they were counting on to stay safe from the pandemic and knew the risks the workers were taking.

A newscast on SUR Peru Sunday showed residents of Lima at their windows clapping and thanking the masked sanitation workers loading bags of trash into a garbage truck. The screen read, “Coronavirus: Cleaning in Lima, Anonymous Heroes.” Residents knew whose labor they were counting on to stay safe from the pandemic and knew the risks the workers were taking.

The global capitalist economy has quickly stumbled into recession, a process already unfolding before the COVID-19 pandemic came into full view. The effects of the spreading virus have led to rolling closures and shutdowns to large swathes of different international economies, inducing a full-blown crisis that is now breathlessly impacting people across the world.

The global capitalist economy has quickly stumbled into recession, a process already unfolding before the COVID-19 pandemic came into full view. The effects of the spreading virus have led to rolling closures and shutdowns to large swathes of different international economies, inducing a full-blown crisis that is now breathlessly impacting people across the world.

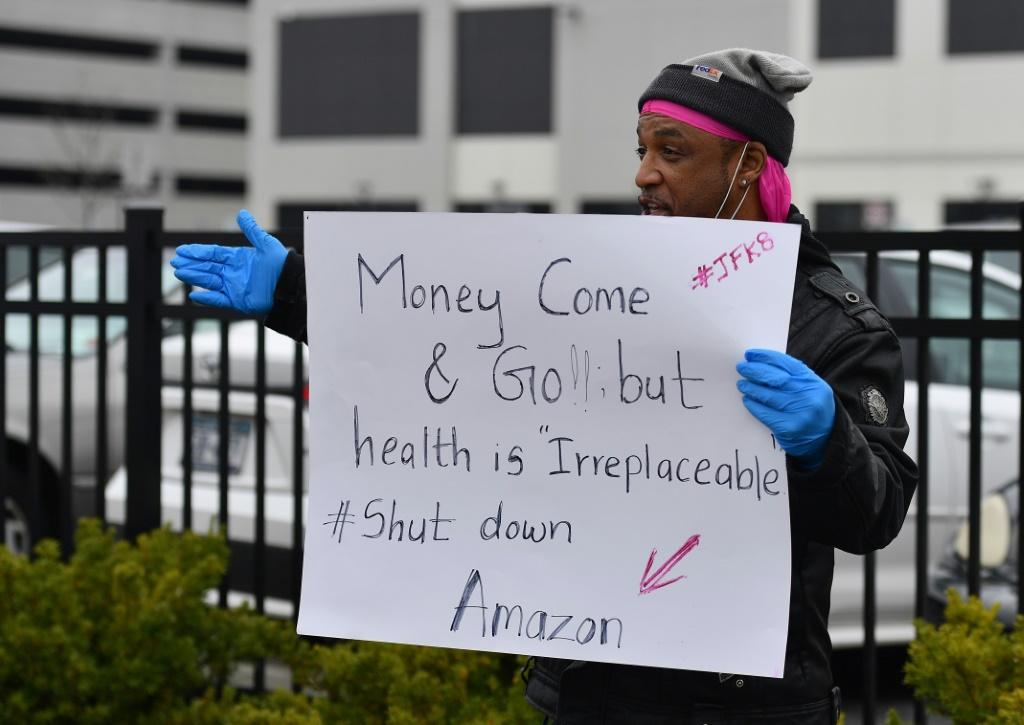

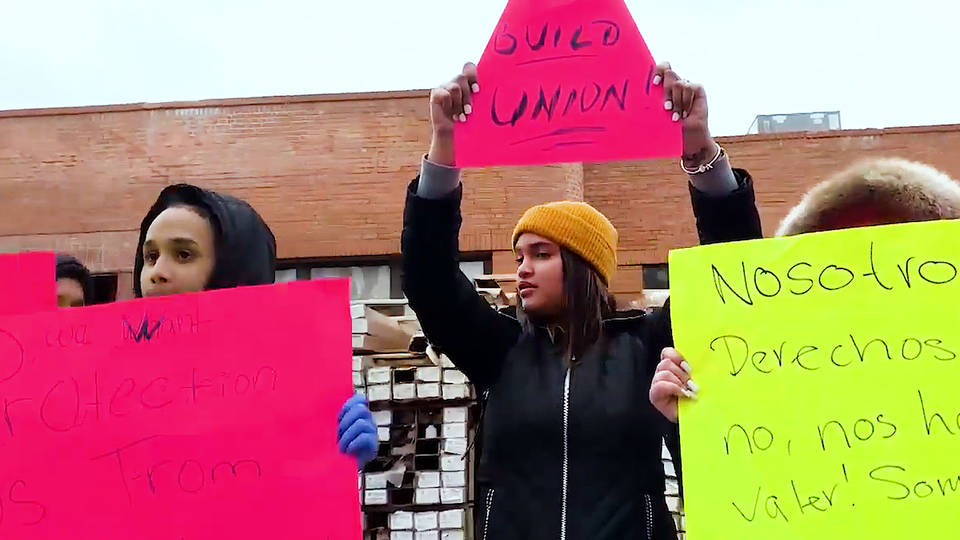

Across the United States we are seeing

Across the United States we are seeing

This article was written for L’Anticapitaliste, the weekly newspaper of the New Anticapitalist Party (NPA) of France.

This article was written for L’Anticapitaliste, the weekly newspaper of the New Anticapitalist Party (NPA) of France.

I believe that there is an ideological war going on right now and that the left needs to be prepared to do battle. In the very first days of this crisis, we saw moratoriums on evictions, expedited unemployment benefits, CA housing the homeless in hotels, and prisoners being released in OH. All of these measures showed that the market, profits and our repressive apparatus are not untouchable. This crisis has opened up questions of profit vs human need in fundamental ways.

I believe that there is an ideological war going on right now and that the left needs to be prepared to do battle. In the very first days of this crisis, we saw moratoriums on evictions, expedited unemployment benefits, CA housing the homeless in hotels, and prisoners being released in OH. All of these measures showed that the market, profits and our repressive apparatus are not untouchable. This crisis has opened up questions of profit vs human need in fundamental ways.

This article was written for L’Anticapitaliste, the weekly newspaper of the New Anticapitalist Party (NPA) of France.

This article was written for L’Anticapitaliste, the weekly newspaper of the New Anticapitalist Party (NPA) of France.

The global coronavirus outbreak is not (fortunately) the end of civilization, nor is it (unfortunately) the end of capitalism. It is, however, a very deep systemic crisis with interlocking public health, environmental and economic dimensions — and reveals the need for a profound social transformation both in the United States and internationally.

The global coronavirus outbreak is not (fortunately) the end of civilization, nor is it (unfortunately) the end of capitalism. It is, however, a very deep systemic crisis with interlocking public health, environmental and economic dimensions — and reveals the need for a profound social transformation both in the United States and internationally.