Disreputable writers and outlets, often operating under the aegis of “independent journalism” with purportedly “leftwing” views, are spreading corrosive propaganda and disinformation that aims to strip Syrians of political agency

Disreputable writers and outlets, often operating under the aegis of “independent journalism” with purportedly “leftwing” views, are spreading corrosive propaganda and disinformation that aims to strip Syrians of political agency

[The following Open Letter was a collaborative effort of a group of Syrian writers and intellectuals and others who stand in solidarity with them. It is signed by activists, writers, artists, and academics from Syria and more than forty other countries in Africa, Asia, Europe, the Middle East, North America, Oceania, and South America, and appears in multiple languages: English, Arabic, French, Spanish, Greek, Italian, Russian, and Portuguese.]

Since the beginning of the Syrian uprising ten years ago, and especially since Russia intervened in Syria on behalf of Bashar al-Assad, there has been a curious and malign development: the emergence of pro-Assad allegiances in the name of “anti-imperialism” among some who otherwise generally identify as progressive or “left,” and the consequent spread of manipulative disinformation that routinely deflects attention away from the well-documented abuses of Assad and his allies. Portraying themselves as “opponents” of imperialism, they routinely exhibit a highly selective attention to matters of “intervention” and human rights violations that often aligns with the governments of Russia and China; those who disagree with their highly-policed views are frequently (and falsely) branded as “regime change enthusiasts” or dupes of western political interests.

The divisive and sectarianizing role played by this group is unmistakable: in their simplistic view, all pro-democracy and pro-dignity movements that go against Russian or Chinese state interests are routinely portrayed as the top-down work of Western interference: none are autochthonous, none are of a piece with decades of independent domestic struggle against brutal dictatorship (as in Syria), and none truly represent the desires of people demanding the right to lives of dignity rather than oppression and abuse. What unites them is a refusal to contend with the crimes of the Assad regime, or even to acknowledge that a brutally repressed popular uprising against Assad took place.

These writers and outlets have mushroomed in recent years, and have often positioned Syria at the forefront of their criticisms of imperialism and interventionism, which they characteristically restrict to the west; Russian and Iranian involvement is generally ignored. In doing so, they have sought to align themselves with a long and venerable tradition of internal domestic opposition to the abuses of imperial power abroad, not only but quite often issuing from the left.

But they do not rightfully belong in that company. No one who explicitly or implicitly aligns themselves with the malignant Assad government does. No one who selectively and opportunistically deploys charges of “imperialism” for reasons of their particular version of “left” politics rather than opposing it consistently in principle across the globe — thereby acknowledging the imperialist interventionism of Russia, Iran, and China — does.

Often under the guise of practicing “independent journalism,” these various writers and outlets have functioned as chief sources of misinformation and propaganda about the ongoing global disaster that Syria has become. Their reactionary, inverted Realpolitik is as fixated on top-down, anti-democratic “power politics” as that of Henry Kissinger or Samuel Huntington, just with the valence reversed. But this maddeningly oversimplifying rhetorical move (“flipping the script” as one of them once put it), as appealing as it might be to those eager to identify who the “good guys” and “bad guys” are at any given place on the planet, is really an instrument of tailored flattery for their audiences about the “true workings of power” that serves to reinforce a dysfunctional status quo and impede the development of a truly progressive and international approach to global politics, one that we so desperately need, given the planetary challenges of responding to global warming.

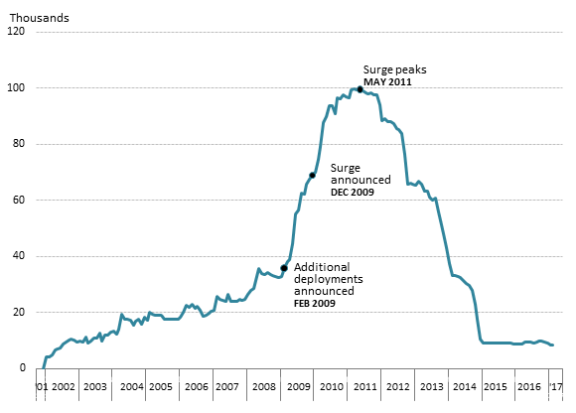

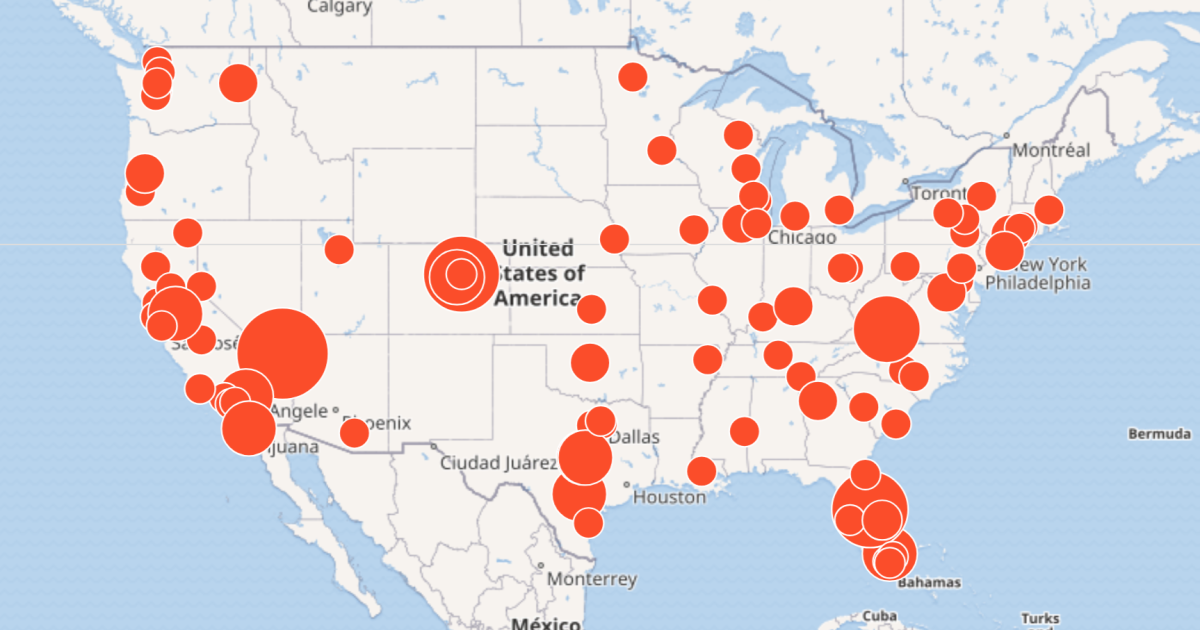

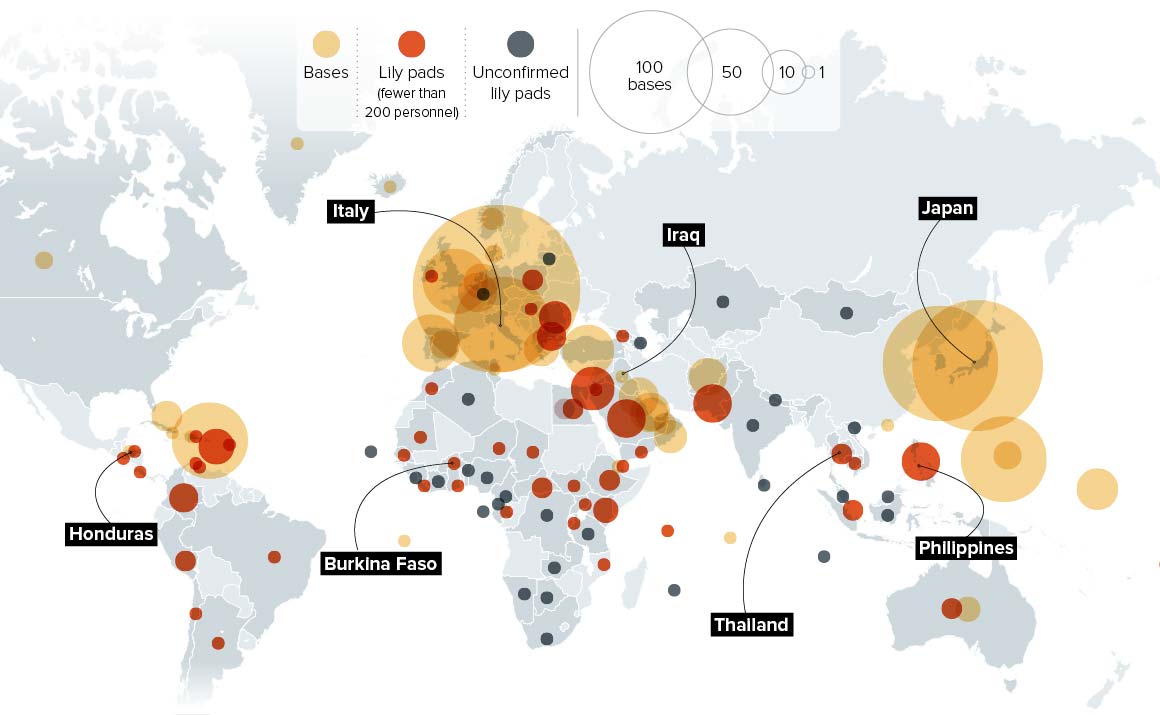

The evidence that US power has itself been appallingly destructive, especially during the Cold War, is overwhelming: all across the globe, from Vietnam to Indonesia to Iran to Congo to South and Central America and beyond, the record of massive human rights abuses accumulated in the name of fighting Communism is clear. And in the post-Cold War period of the so-called “War on Terror,” American interventions in Afghanistan and Iraq have done nothing to suggest a fundamental national change of heart.

But, America is not central to what has happened in Syria, despite what these people claim. The idea that it somehow is, all evidence to the contrary notwithstanding, is a by-product of a provincial political culture which insists on both the centrality of US power globally as well as the imperialist right to identify who the “good guys” and the “bad guys” are in any given context.

The ideological alignment of rightwing admirers of Assad with this kind of authoritarian-friendly “leftism” is symptomatic of this, and indicates that the very real and very serious problem lies elsewhere: what to do when a people is as abused by their government as the Syrian people have been, held captive by those who think nothing of torturing, disappearing, and murdering people for even the slightest hint of political opposition to their authority? As many countries move closer and closer to authoritarianism and away from democracy, this seems to us a profoundly urgent political question to which there is yet no answer; and because there is no answer, all across the globe there is growing impunity on the part of the powerful, and growing vulnerability for the powerless.

About this, these “anti-imperialists” have no helpful words. About the profound political violence visited upon the Syrian people by the Assads, the Iranians, the Russians? No words. Forgive us for pointing out that such erasure of Syrian lives and experiences embodies the very essence of imperialist (and racist) privilege. These writers and bloggers have shown no awareness of the Syrians, including signatories to this letter, who risked their lives opposing the regime, who have been incarcerated in the Assads’ torture prisons (some for many years), lost loved ones, had friends and family forcibly disappeared, fled their country – even though many Syrians have been writing and speaking about these experiences for many years.

Collectively, Syrian experiences from the Revolution to the present pose a fundamental challenge to the world as it appears to these people. Syrians who directly opposed the Assad regime, often at great cost, did not do so because of some Western imperialist plot, but because decades of abuse, brutality, and corruption were and remain intolerable. To insist otherwise, and support Assad, is to attempt to strip Syrians of all political agency and endorse the Assads’ longstanding policy of domestic politicide, which has deprived Syrians of any meaningful say in their government and circumstances.

We Syrians and supporters of the Syrian people’s struggle for democracy and human rights take these attempts to “disappear” Syrians from the world of politics, solidarity, and partnership as quite consistent with the character of the regimes these people so evidently admire. This is the “anti-imperialism” and “leftism” of the unprincipled, of the lazy, and of fools, and only reinforces the dysfunctional international gridlock exhibited in the UN Security Council. We hope that readers of this piece will join us in opposing it.

Signatories [Affiliations for identification purposes only]

Syrians

Ahmad Aisha, journalist and translator (Turkey)

Ali Akil, Founder & Spokesperson, Syrian Solidarity New Zealand (Aotearoa/New Zealand)

Amina Masri, Activist/Educator (USA)

Amr al-Azam, Professor of Middle East History and Anthropology, Shawnee State University (USA)

Asmae Dachan, Syrian-Italian Journalist (Italy)

Ayaat Yassin-Kassab, Student, University of Oxford (UK)

Aziz Al-Azmeh, University Professor Emeritus, Central European University (Austria)

Bakr Sidki, translator and columnist (Turkey)

Banah el Ghadbanah, University of California, San Diego (USA)

Bisher Ghazal-Aswad, Doctor, NHS (UK)

Bushra A., Syria Solidarity New York City (USA)

Dellair Yousef, writer and director, Berlin (Germany)

Dr. Mohammed Zaher Sahloul, President, MedGlobal & Founder, American Relief Coalition for Syria (USA)

Faraj Bayrakdar, poet (Sweden)

Farouk Mardam-Bey, publisher and writer, Paris (France)

Fouad M. Fouad, Professor, American University of Beirut (Lebanon)

Fouad Roueiha, Activist (Italy)

Ghayath Almadhoun, poet (Germany)

Haian Dukhan, Associate Research Fellow, Centre for Syrian Studies, University of St. Andrews (UK)

Haid Haid, Senior Research Fellow, Chatham House (UK)

Hala Alabdalla, Filmmaker (France)

Hassan Nifi, writer (Turkey)

Irène Labeyrie Chaya, Architect & Former Teacher at the Faculty of Architecture, University of Qalamun, Deir Atiya, Syria

Joseph Daher, Syrian/Swiss Academic, University of Lausanne/European University Institute (Switzerland)

Karam Nachar, academic and writer

Karam Shaar, Senior Analyst, New Zealand Treasury (New Zealand)

Karim Al-Afnan, Journalist (UK)

Lara el Kateb, Member of the Alliance of Middle Eastern and North African Socialists

Leila Al-Shami, Writer/Activist (Scotland)

Lubayed Aljundi, PhD Candidate, SOAS, University of London (UK)

Mahmoud el Wahb, writer (Turkey)

Marcelle Shehwaro, New York NY (USA)

Marcus Halaby, British-Syrian Writer and Labour Party Member (UK)

Marwa Daoudy, Associate Professor, Georgetown University (USA)

Mayson Almisri, Syria Civil Defence – White Helmets, co-winner of the Gandhi Peace Award 2021 (Canada)

Miream Salameh, Syrian Artist (Australia)

Mohamed Al Rashi, Actor (France)

Mohamed Samawi, Homs, PR

Mohamed T. Khairullah, Mayor, Borough of Prospect Park, New Jersey (USA)

Mohammad Al Attar, Writer, Playwright, Berlin (Germany)

Mohja Kahf, Professor (USA)

Najwa Affash, President of the Hani Association, Paris (France)

Nidal Betare, Journalist (USA)

Nisrine Al Zahre, academic and writer (France)

Noor Ghazal Aswad, Doctoral Candidate, University of Memphis (USA)

Odai Al Zoubi, Writer (Sweden)

Omar Abbas, University of California Riverside (USA)

Omar Qaddour, novelist and journalist (France)

Orwa Khalifa, writer (Turkey)

Osama Alomar, Writer (USA)

Rahaf Aldoughli, Lecturer in Middle East and North Africa Studies, Lancaster University (UK)

Ramah Kudaimi, organizer, Washington (USA)

Ramzi Choukair, Actor and Director, Kawalisse Theatre Company (France)

Sadek Abd Alrahman, writer (Turkey)

Salam Abbara, Doctor and Activist, Paris (France)

Salam Said, Academic (Germany)

Saleem Albeik, Writer/Journalist, Palestinian/Syrian (France)

Samar Yazbek, novelist (France)

Sami Haddad, Activist (Italy)

Sherifa Zuhur

Shiyam Galyon, War Resisters League (USA)

Taha Bali, physician and writer (USA)

Touhama Ma’roof, dentist (Turkey)

Victorios Bayan Shams, Journalist (Brazil)

Wael Khouli, Physician Executive – B E Smith, Michigan (USA)

Yasmine Merei, Writer & Journalist and Head of Women for Common Space, Berlin (Germany)

Yasser Khanger, Poet from the occupied Golan

Yasser Munif, Emerson College (USA)

Yassin al-Haj Saleh, Writer, Former Political Prisoner (Germany)

Yassin Swehat, Journalist and Editor (Germany-Spain)

Yazan Badran, PhD student, Vrije Universiteit and SyriaUntold (Belgium)

Others

A Hak (UK)

Abdelrahman Elbanna, Lyndhurst, NJ (USA)

Abdullsh Hayed, Paris (France)

Abdulrahman Hallak, Kuwait (Kuwait)

Abdul-Wahab Kayyali, Researcher, Princeton University (Canada)

abraham Weizfeld PhD, Direct Democracy Movement

Adam Sabra, Professor of History, University of California, Santa Barbara (USA)

Adam Shatz, Writer, Brooklyn (USA)

Aditya Sarkar, University of Warwick (UK)

Adnan Salim, Idoo Madrid (Spain)

Agnes Favier, Part Time Professor, European University Institute

Agostino Soldini, trade union secretary (Switzerland)

Ahlam Zeineddine, Beirut (Lebanon)

Ahmad Matar, chef (Palestinian, Germany)

Ahmed Sakkal, Baltimore, MD (USA)

Aidan Geboers, Financial Professional (UK)

Akram Aboud, Riyadh (Saudi Arabia)

Al Hammood, Centreville, VA (USA)

Alan Wald, H. Chandler Davis Collegiate Professor Emeritus, University of Michigan (USA)

Alberto Savioli, archaeologist and writer

Aldo Cordeiro Sauda, Editora Contrabando, São Paulo (Brazil)

Aldo Garzia, journalist (Italy)

Alessandra Mezzadri, Senior Lecturer, SOAS, University of London (UK)

Alessia Bleve, Social Space Zei Aps – Circolo arci Lecce (Italy)

Alex De Jong, Co-Director, International Institute for Research and Education (Netherlands)

Alex Johnson, Syria Solidarity Australia (Australia)

Ali Bakeer, Senior Researcher, Ibn Khaldun Center (Turkey)

Ali Fathollah-Nejad, Freie Universität Berlin (Germany)

Ali Moravej, Manchester, CT (USA)

Ali Samadi Ahadi, Filmmaker (Germany)

Aliaa Tabbaa,, Hellin ((Spain)

Alicia Fdez Gómez, Oviedo (Spain)

Al-Sheik Hussein, Helsinki (Finland)

Amahl Bishara, Tufts University (USA)

Amal Mouhamad, Berlin (Germany)

Amal Sakkal, Charleston, WV (USA)

Aman Doughan, Beirut (Lebanon)

Amina A., Syria Solidarity New York City (USA)

Ammar Al-Ghabban, Independent educator (UK)

Anahita Razmi, Visual Artist (Germany)

Andrea Love, Educator (USA)

Andrew Berman, Committee in Solidarity with the People of Syria — CISPOS (USA)

Andy Heintz, Ames, IA (USA)

Anette Laszkiewitz (Germany)

Angelica Lepori, member of the cantonal parliament

Ani White, Melbourne (Australia)

Anis Mansouri, Special Education Teacher & Coordinator, Tunisian Internationalists in Switzerland (Switzerland)

Anja Matar, travel agent (Germany)

Ann Eveleth, Anti-War Activist, Washington DC (USA)

Ann Morgen, Dundas (Canada)

Anna Alboth, Civil March For Aleppo (Germany/Poland)

Anna Ferris, Philadelphia, PA (USA)

Anna Sailer, University of Goettingen (Germany)

Anne Michel, feminist and trade unionist (Switzerland)

Anne-Kathryn Bathe, Berlin (Germany)

Anne-Marie McManus, Berlin (Germany)

Ansar Jasim, political researcher, Berlin (Germany)

Anthony Ratcliff, California State University, Los Angeles (USA)

Antonio Moscato, former professor at the University of Salento (Italy)

Anya Briy, PhD student, Binghamton University (USA)

Arash Azizi, PhD Candidate, New York University (USA)

Arianna Parisato (Italy)

Ariel Dorfman, Writer & former advisor to the government of Salvador Allende (Chile/USA)

Art Young, solidarity activist (Canada)

Arthur Esparza, Everett, WA (USA)

Ashley Smith, Member of DSA and the Tempest Collective (USA)

Athena Moss, Journalist (Greece)

Au Loong-Yu, global justice and labour campaigner (Hong Kong)

Austin G Mackell (Australia)

Avanzata Proletaria – http://www.avanzataproletaria.it (Italy)

Barbara Blaudzun, MA Student, Humboldt University of Berlin (Germany)

Barbara Epstein, Professor Emerita, University of California, Santa Cruz (USA)

Basem Kan, Göteborg (Sweden)

Bashir Abu-Manneh, Reader, University of Kent (UK)

Becky Carroll, Co-Founder, Stand With Aleppo Campaign (USA)

Ben Manski, Assistant Professor of Sociology, George Mason University (USA)

Bernard Dreano, Activist (France)

Bilal Ansari, Faculty Associate & Director of the Islamic Chaplaincy Program, Hartford Seminary (USA)

Bill Fletcher, Jr., Past President of the TransAfrica Forum (USA)

Bill Mullen, West Lafayette, IN (USA)

Bill Weinberg, Journalist and Author (USA)

Birgitte Jensen, Vejle (Denmark)

Boris Thiolay Paris (France)

Brett Ogaard, Seattle, WA (USA)

Brian Aboud, Montréal, Quebec (Canada)

brian bean, organizer/journalist, Rampant Magazine, Tempest Socialist Collective (USA)

Brigitte Herremans, Gentbrugge (Belgium)

Bruno Buonomo, researcher, ecosocialist activist (Italy)

Camila Pastor, Research Professor, History Dept., Center for Research and Teaching in Economics (Mexico)

Carol Akhras, Bridgeview, IL (USA)

Carol Murchie, Newport, RI (USA)

Caroline Gilbert, Retired HELP Center Counselor, University of Minnesota (USA)

Caterina Coppola, Activist (Italy)

Catherine Coquio (France)

Catherine Estrade, Singer (France)

Catherine Samary, Economist, Member of the Scientific Council of ATTAC (France)

Cedric Beidatsch, Retired Cook (Australia)

Cesare Quinto, photographer (Italy)

Charles Post, Brooklyn, NY (USA)

Charles-André Udry, Economist, Editor, alencontre.org (Switzerland)

Chaza Charafeddine, Beirut (Lebanon)

Cheryl Zuur, former President, AFSCME Local 444 (USA)

Chris Keulemans, writer and journalist (Netherlands)

Christian Dandrès, Member of Parliament (Conseil National) (Switzerland)

Christian Shaughnessy, Democratic Socialists of America, Inland Empire Chapter (USA)

Christian Varin, Civil Servant & Member of the International Commission of the Nouveau Parti Anticapitaliste (France)

Christin Lüttich, Expert on Syria, German–Syrian Solidarity Initiative “Adopt a Revolution” (Germany)

Christoph Reuter, journalist and author, Berlin (Germany)

Cinzia Nachira, Researcher, University of Florence (Italy)

Claire Martenot, feminist and trade unionist (Switzerland)

Claire Nolan, Dublin (Ireland)

Claude Marill, Retired Educator & Trade Unionist, Syndicat National des personnels de l’éducation et du social (France)

Claude Szatan, activist (France)

Clay Claiborne, Director, Vietnam: American Holocaust, Linux Beach Productions (USA)

Colette Morrow, Professor of English, Purdue University Northwest (USA)

Colleen Keyes, Adjunct Faculty, Hartford Seminary (USA)

Cory Strachan, Manistee, MI (USA)

Craig Larkin, Senior Lecturer, King’s College London (UK)

Cristèle Jonnart, Ohain (Belgium)

Cristina Cardeño, Mexico City (Mexico)

Dan Buckley, International Marxist-Humanist Organization (USA)

Dan Cahill, Local Union 18, IUPAT, New Jersey (USA)

Dan La Botz, New Politics Journal (USA)

Dana Mohseni, Göteborg (Sweden)

Daniel Fischer, Food Not Bombs (USA)

Daniel Ford, Denver, CO (USA)

Daniela Vitkova, Sofia (Bulgaria)

Daniele Rugo, London, England (UK)

Danilo Milinin, Beograd, Beograd (Serbia)

Danny Postel, Writer, Member, Internationalism from Below (USA)

Dario Brandi, documenter (Italy)

Dario Lopreno, Geographer (Switzerland)

Darren Fenwick, Silver Spring MD (USA)

David Bedggood, Syria Solidarity Discussion and Strategy Group (Aotearoa/New Zealand)

David Brophy, Senior Lecturer in History, University of Sydney (Australia)

David L. William, Peregrine Forum of Wisconsin (USA)

David Letwin, South Orange, NJ (USA)

David McNally, Cullen Distinguished Professor of History, University of Houston (USA)

David N. Smith, Professor of Sociology, University of Kansas (USA)

David Turpin, Anti-War Activist (USA)

David Wearing, Senior Teaching Fellow, SOAS, University of London (UK)

David Westman, Communist Voice Organization, USA

Diane Michellini, Dallas, TX (USA)

Diego Giachetti, retired teacher (Italy)

Dilip Simeon, Teacher (India)

Dina Matar, Reader, SOAS, University of London (UK)

Donya Alinejad, Lecturer & Postdoctoral Researcher, Universities of Amsterdam & Utrecht (Netherlands)

Dora Manna, Activist (Italy)

Dylan Connor, singer-songwriter and human rights activist, Connecticut (USA)

Dylan Terpstra, Randolph, NJ (USA)

Ed Sutton, Media Activist and Mutual Aid Organizer (USA)

Edin Hajdarpasic, Associate Professor of History, Loyola University Chicago (USA)

Eileen Boyle, Dublin (Ireland)

Elena De Piccoli, Activist (Italy)

Eleni Varikas, Emerita Professor of Political Science, Université de Paris 8 (France)

Elias Khoury, novelist (Lebanon)

Elizabeth Bard, Little Rock AR (USA)

Elizabeth Lalasz, Chicago, IL (USA)

Elsa Wiehe, Boston University (USA)

ELza Mardirossian Matouk, Dollard-Des Ormeaux (Canada)

Emma Wilde Botta, New Politics Journal (USA)

Emran Feroz, Journalist (Germany)

Enrico De Angelis, independent researcher, Berlin (Germany)

Enrico Pulieri MPhil / PhD SOAS University of London (UK)

Enrico Semprini, Sicobas activist (Italy)

Enzo Traverso, Historian, Cornell University (USA)

Eric G., Seattle, WA (USA)

Eric Toussaint, Member of the International Council of the World Social Forum (Belgium)

Estella Carpi, University College London, Istanbul (Turkey)

Eugene Zaikonnikov, Nesttun (Norway)

Eylaf Bader Eddin, Philipps-Universität Marburg \ Post-doc (Germany)

Fabio Alberti, Rome (Italy)

Fabio Bosco, CSP-Conlutas (Brazil)

Fabrizio Gigliani, Trade Union Delegate USB Public Employment (Italy)

Fadi Dayoub, Castelnau Le Lez (France)

Farah Baba, Feminist activist (Lebanon)

Farhad Mirza, Berlin (Germany)

Farizah JAHJAH, Reims (France)

Fatemeh Masjedi, Research Associate, Centre Marc Bloch, Berlin (Germany)

Fatma Alhaji, Helsingborg (Sweden)

Fazlur Rahmat (Indonesia)

Fiorella Sarti, Activist and Translator (Italy)

Firas Aljanadi Leeds (UK)

Firoze Manji, Publisher, Daraja Press (Canada)

Francesca Burns, New York, NY (USA)

Francesca Giura, Activist (Italy)

Francesca Scalinci, Translator and Writer (Italy)

Francis Sitel, Member of the National Animation Team of ENSEMBLE! (France)

Franco Casagrande (Italy)

Franco Turigliatto, former Senator, Anticapitalist Left (Italy)

Françoise Clement, Chatou ((France)

Frankie Hill, Self-Employed (New Zealand)

Frieda Afary, Producer of Iranian Progressives in Translation (USA)

Gabriel Huland, PhD candidate & teaching assistant, SOAS, University of London (UK)

Gail Vignola, South Orange NJ (USA)

Gareth Kenny, Dublin (Ireland)

Gaya Nagahawatta, Translator, (Sri Lanka)

Gennaro Gervasio, Associate Professor in History and Politics of the Middle East, Roma Tre University (Italy)

George De Stefano, Brooklyn NY (USA)

George Monbiot, Author, Journalist & Environmental Activist (UK)

George Wilmers, mathematician, University of Manchester, (retired) (UK)

Gerard Lauton, academic, member of association For a Free and Democratic Syria (France)

Germano Monti, internationalist activist (Italy)

Ghaith Almahayni, Istanbul (Turkey)

Gilbert Achcar, Professor, SOAS, University of London (UK)

Gilberto Conde, Research Professor, El Colegio de México (Mexico)

Giovanna De Luca, Translator-Activist (Italy)

Giovanna Vertova, economist at the University of Bergamo (Italy)

Giuseppe Cossuto, Historian (Italy)

Giuseppe Visconti, Salerno (Italy)

Golineh Atai, TV Journalist (Germany)

Graciela Monteagudo, University of Massachusetts Amherst (USA)

Grant Padgham, Ashford, England (UK)

Günther Orth, Translator (Germany)

Gustavo Gozzi, professor at the University of Bologna (Italy)

Habib Nassar, activist/lawyer (Netherlands)

Hadrien Buclin, Academic & Deputy Ensemble à Gauche in the Parliament of the Governorate of Vaud (Switzerland)

Haideh Moghissi, Emerita Professor, York University (Canada)

Haley Wilson, Westerville, OH (USA)

Halimah El Azem, Berlin (Germany)

Hannu Reime, Helsinki (Finland)

Harald Etzbach, Journalist (Germany)

Harout Akdedian, Senior Fellow, Striking from the Margins Project, Central European University (USA)

Harsh Kapoor, Independent researcher and editor, (India/France)

Hassan KRAYEM, Amman (Jordan)

Hayfaa Tahan, Milton (Canada)

Hazar Tahan, Beirut (Lebanon)

Heather A. Brown, Associate Professor of Sociology, Westfield State University (USA)

Helen Lackner, Research Associate, SOAS, University of London (UK)

Helen Scott, Burlington, VT (USA)

Hilary Austin, Chicago, IL (USA)

Hilary Oxley, Palmerston North (New Zealand)

Hiroki Okazaki, University lecturer (Japan)

Howard Brick, Louis Evans Professor of History, University of Michigan, USA

Howie Hawkins, 2020 Green Party Candidate for President (USA)

Huda Tahan, Beirut (Lebanon)

Hussam Alshabi, Dubai (UAE)

Ibrahim Chahoud, Berlin (Germany)

Idrees Ahmad, Lecturer in Digital Journalism, University of Stirling (UK)

Ikram Abdelfattah, Beirut (Lebanon)

iris aulbach (Germany)

Isabelle Peillen-Debs Beirut (Lebanon)

Isabelle THIEULEUX, PARIS (France)

Ismail ElAchkar, Khobar, (Saudi Arabia)

Ivan Handler, Retired CIO from Illinois Medicaid & the Health Information Exchange (USA)

Izzat Darwazeh, Professor, University College London (UK)

Jack McGinn, London (UK)

jacob Miller Brampton (Canada)

Jacques Raillane, Paris (France)

Jaime Pastor, Professor of Political Science, Universidad Nacional de Educación a Distancia (Spain)

Jairus Banaji, SOAS, University of London (UK)

James Dickert, Retired Computer Engineer (USA)

James Dickins, Prof. of Arabic, University of Leeds (UK)

James Hamill Leicester (UK)

James Mullally, Human Rights Activist, British Columbia (Canada)

James Smith, Dallas, TX (USA)

Jamie Mayerfeld, Professor of Political Science, University of Washington, Seattle (USA)

Jan Malewski, Editor, Inprecor (France)

Jan Toporowski, SOAS University of London (UK)

Jane England, Writer (Aotearoa/New Zealand)

Janet Afary, Mellichamp Chair in Global Religion and Modernity, University of California, Santa Barbara (USA)

Janet Robin Bogle, Grandmother (Aotearoa/New Zealand)

Janette Corcelius, Lorton, VA (USA)

Janick Schaufelbuehl, Associate Professor, University of Lausanne (Switzerland)

Jason Schulman, Lehman College, City University of New York (USA)

Javier Sethness, Los Angeles CA (USA)

Jean Batou, Historian and Deputy in the Parliament of the Governorate of Geneva (Switzerland)

Jean-Michel Dolivo, Lawyer & Former Deputy, Ensemble à Gauche, Parliament of the Governorate of Vaud (Switzerland)

Jeff Weintraub, Bryn Mawr College, PA (USA)

Jen MacLennan, Independent Media, Syria Solidarity Activist, London (UK)

Jenna Mushin, Coventry, CT (USA)

Jenny Morgan, film-maker (UK)

Jens Hanssen, University of Toronto (Canada)

Jens Lerche, Reader, SOAS, University of London (UK)

Jens-Matin Rode, Berlin (Germany)

Jessy Nassar, PhD candidate, King’s College London (Lebanon)

Joachim Haberlen, University of Warwick, (UK)

Joan Connelly, Secretary, Retired USA

Joanne Demchok, Bethesda, MD (USA)

Joanne Roberts (Australia)

Joel Beinin, Professor of Middle East History, Emeritus, Stanford University (USA)

Joël Jovet, Paris (France)

Joey Ayoub, Assoc. Doctoral Researcher, Univ. of Zurich, founder of ‘The Fire These Times’, writer/journalist (Switzerland)

John A Imani (USA)

John Clarke, Packer Visitor in Social Justice, York University, Toronto (Canada)

John Dunn, former striking coal miner & branch committee member, National Miners Union, Darbyshire Branch (UK)

John Feffer, Director, Foreign Policy In Focus, Institute for Policy Studies (USA)

John Kahler, MD, FAAP (Fellow of the American Academy of Pediatrics) (USA)

John Reimann, former recording secretary, Carpenters Union Local 713, Editor, Oakland Socialist (USA)

John Treat, New York NY (USA)

Jonas Ecke, Berlin (Germany)

Joseph Green, Communist Voice Organization (USA)

Joseph Halevi, Macquarie University, Sydney; International University College of Turin

Josepha Ivanka (Joshka) Wessels, Senior Lecturer, Malmö University (Sweden)

Joshua Cohen, Editor, Boston Review; Distinguished Senior Fellow, UC Berkeley; faculty, Apple Univ. (USA)

Joshua Evangelista, journalist (Italy)

Judith Deutsch, psychoanalyst, Toronto (Canada)

Julia Bar-Tal, farmer, Berlin (Germany)

Julien Salingue, Director of the newspaper and website l’Anticapitaliste, Nouveau Parti Anticapitaliste (France)

Juliette Harkin, Writer (UK)

Julnar Tahan, Halba north (Lebanon)

Kaori Hizume, TV producer, Tokyo (Japan)

kawabata erkin (Japan)

Kay Brainerd, Belleville, MI (USA)

Kelly Grotke, PhD, writer, greater Boston (USA)

Ken Hiebert, Palestine Solidarity Activist (Canada)

Kevin B. Anderson, Professor of Sociology, University of California, Santa Barbara (USA)

Kevork Assadourian, Yerevan (Armenia)

Khaled Ghannam Warehouse Manager (Australia)

Khaled Mansour, writer (Egypt)

Khaled Saghieh, journalist and writer, Beirut (Lebanon)

Konstantin Rintelmann, PhD candidate, University of Edinburgh (UK)

kris Juhl, Mckinleyville, CA (USA)

L R, Bern (Switzerland)

Lauren Langman, Professor of Sociology, Loyola University of Chicago (USA)

laurent soubise, Lyon (France)

Laurie King, Associate Professor of Teaching, Department of Anthropology, Georgetown University (USA)

Leah Wild, Cheltenham, England (UK)

Lee Wengraf, Queens, NY (USA)

Leonie O. Dowd, Dublin (Ireland)

Leyla Dakhli, Researcher, CNRS (France)

Lilia Marsali, Paris (France)

linda mattes, Jbail (Lebanon)

Lisa Albrecht, Retired University of Minnesota Professor, Social Justice (USA)

Lisa Morton, Newton, NJ (USA)

Lisa Perrine (France)

Lisa Wedeen, Mary R. Morton Professor of Political Science and the College, University of Chicago (USA)

Lisbeth Gouin (France)

Livia Wick, Associate Professor, American University of Beirut (Lebanon)

Liz Elkind, Edinburgh (UK)

Lois Weiner, Professor Emerita, New Jersey City University (USA)

Lorenzo Declich, Islamologist

Loretta Facchinetti, Activist (Italy)

Louay Ojjeh, Neuilly-sur-seine (France)

Lucia Sorbera, Sydney (Australia)

Luciano Nuzzo, Professor of Sociology of Law, Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro (Brazil)

Luke Alexander, Leumeah (Australia)

Lydia Beattie, Committee in Solidarity with the People of Syria – CISPOS (USA)

Mahdi Ghodsi, Economist, Vienna Institute for International Economic Studies (Austria)

Maher Barotchi, Sheffield (UK)

Mahvish Ahmad, Assistant Professor in Human Rights and Politics, London School of Economics (LSE) (UK)

Mai Taha, Goldsmiths, University of London (UK)

Maire Kelly, Activist, Berlin (Germany)

Majd A Bukit, Mertajam (Malaysia)

Mamoun DIB, Avrillé (France)

Marese Hegarty, Community Development Worker, Irish Syria Solidarity Movement (Ireland)

Margo Harkin Derry (UK)

Maria Van innis, Namur (Belgium)

Mariana Morena, Buenos Aires (Argentina)

Mariluz Secilla Souto (Spain)

marina caruso, paris (France)

Marina Centonze, Activist (Italy)

Mark Boothroyd, London (UK)

Mark Goudkamp, ESL and History Teacher, Syria Solidarity Australia (Australia)

Mark LeVine, Irvine, CA (USA)

Markus Bickel, Tel Aviv (Israel)

Marta Tawil-Kuri, Research Professor, El Colegio de México (Mexico)

Martti Koskenniemi, Prof. of International Law, University of Helsinki (Finland)

Mary Ellen Davis, Montréal, Quebec (Canada)

Mary Killian, Pianist/Music Teacher, Berlin (Germany)

Mary Lynn Murphy, Committee in Solidarity with the People of Syria — CISPOS (USA)

Mary Rizzo, Translator-Activist (Italy)

Matilde Bei Clementi, activist (Italy)

Matteo Pronzini, member of the cantonal parliament (Switzerland)

Max Weiss, Associate Professor of History and Near Eastern Studies, Princeton University (USA)

Mayssoun Sukarieh, Senior Lecturer, King’s College London (UK)

Mazen Halabi, Activist (USA)

Meghan Keane, Co-Director of Emergent Horizons (USA)

Meredith Tax, New York, NY (USA)

Michael Albert, ZNet (USA)

Michael Fuller, Mapper, Social Scientist, British Columbia (Canada)

Michael Hirsch, NYC Democratic Socialists of America (USA)

Michael Karadjis, Western Sydney University, Syria Solidarity Australia (Australia)

Michael Kulbat, Lisbon, Santarém (Portugal)

Michael Letwin, Brooklyn, NY (USA)

Michael Löwy, Emeritus Research Director, French National Centre for Scientific Research (CNRS) (France)

Michael Pröbsting, Author, Editor of www.thecommunists.net (Austria)

Michael Santos, Antiwar Activist (USA)

Michel Morziere, activist, member of association For a Free and Democratic Syria (France)

Michelle Cantat, Paris (France)

Michelle Dean, Bristol (UK)

Miguel Urbán, Member of the European Parliament (GUE/NGL) (Spain)

Mike Kurpinski, Tomice (Poland)

Minnie Berman, New York, NY (USA)

Miriam Pickens, Southfield, MI (USA)

Mirko Medenica, Beograd (Serbia)

Miro Sandev, Sydney (Australia)

Mitchell Plitnick, President, ReThinking Foreign Policy, Maryland (USA)

Mo Tabba, Brossard (Canada)

Mohamad Khouli, Committee in Solidarity with the People of Syria — CISPOS (USA)

Mohamed Abdi Nour, General Secretary, Somali Public Trade Union (Somalia)

Molly Crabapple, Artist and Writer (USA)

Mouhab Ibraheem, (Germany)

Mounzer Itani, Berlin (Germany)

Mudassir Nadeem (India)

Muhammed Abbas, Antalya (Turkey)

Mustafa Aljarf, (France)

Myriam Kendsi, Grenoble (France)

Na’eem Jeenah, Executive Director, Afro–Middle East Centre (South Africa)

Nader Hashemi, Director, Center for Middle East Studies, University of Denver (USA/Canada)

Nadia Leïla Aïssaoui, Sociologist (Algeria/France)

Nadia NAFFAKH, Malakoff (France)

Nadia Salam, Troyes (France)

Nadia Samour, Lawyer, Berlin (Germany)

Nadje Al-Ali, Professor of Anthropology and Middle East Studies, Brown University (USA)

Nael Georges, Annemasse (France)

Nagao Koh, Ichikawa (Japan)

Nancy Holmstrom, Professor Emerita, Rutgers University (USA)

Nancy Ko, PhD Student, Columbia University, New York (USA)

Nassim Mehran, Berlin (Germany)

Natasha Hazrati, San Carlos (Nicaragua)

Nathalie Robisco, Bastia (France)

nathan Hutchinson, Boulder, CO (USA)

Navtej Purewal, Professor, SOAS, University of London (UK)

Nazan Üstündağ, Independent Scholar (Germany)

Nick Riemer, University of Sydney (Australia)

Nicola Gandolfi (Spain)

Nicolas Walder, Member of the Federal Parliament, Green Party (Switzerland)

Nigel Gibson, Emerson College (USA)

Nils de Dardel, Lawyer, Former Member of Parliament (Switzerland)

Nizar Flihsn (Kuwait)

noah zweig, (Ecuador)

Noam Chomsky, University of Arizona (USA)

nurlana khalilova (Italy)

Odile Brunet, Lauris (France)

Ofer Neiman, Student, Jerusalem

Olfa Lamloum,, Tunis (Tunisia)

Olivia Hudis, Boulder, CO (USA)

Omar Dewachi, Anthropologist, Rutgers University (USA)

Osama Alhomse, Jeddah (Saudi Arabia)

Ozlem Goner, Brooklyn, NY (USA)

Pam Bromley, independent member, Rossendale Borough City Council (UK)

Paola Rivetti, Dublin (Ireland)

Paolo Gilardi, anti-militarist and historian (Switzerland)

Parvathi Menon, Researcher/Adjunct Lecturer, University of Helsinki (Finland)

Pascale TENANT, Mouettes (France)

Patrick Bond, Professor, University of the Western Cape (South Africa)

Patrick J. O’Dea, Electrician & Trade Unionist (New Zealand)

Paul Fletcher, Crawley, England (UK)

Paula Manthey (Germany)

Payam Ghalehdar, University of Göttingen (Germany)

Penelope Duggan, Editor, International Viewpoint (France)

Pete Brown, Communist Voice Organization (USA)

Pete Klosterman, Human Rights Activist, New York City (USA)

Peter Bohmer, Faculty Emeritus, Evergreen State College (USA)

Peter Chambers, Castle Donington, England (UK)

Peter Hudis, Professor of Philosophy, Oakton Community College (USA)

Peter McLaren, Distinguished Professor in Critical Studies, Chapman University (USA)

Peter Saxtrup Nielsen, Aarhus C, (Denmark)

Phil Gasper, Professor Emeritus, Notre Dame de Namur University (USA)

Piero Maestri, Activist, Milan (Italy)

Pierre Conscience, Communal Deputy, City Council of Lausanne, Ensemble à Gauche – solidaritéS Vaud (Switzerland)

Pierre Vandevoorde (France)

Pina Piccolo, San Jose (Italy)

Polly Kellogg, Retired Professor of Human Relations, St. Cloud State University, Minnesota (USA)

Prabhu Mohapatra, University of Delhi (India)

Pritam Singh, Oxford Brookes University (UK)

Qutaiba Alhusein, Kirke-hyllinge Denmark

Raghu Krishnan, translator and interpreter, Toronto (Canada)

Rahim Laban, Cardiff (UK)

Rajan Hoole, Writer and human rights defender (Sri Lanka)

Rana Issa, American University of Beirut (AUB) (Lebanon/Norway)

Rana Kabbani, Fulham (UK)

Raouia Ben abd El ouahab Casablanca (Morocco)

Rasha Anayah, Baltimore, MD (USA)

Rashad Ali, Resident Senior Fellow, Institute for Strategic Dialogue (UK)

Rashmi Varma, University of Warwick (UK)

Rebecca Lesses, Ithaca, NY (USA)

Rebekka Rexhausen, Project Assistant, Alsharq Reise (Germany)

Rev. Dr. Rachael Keefe, Clergy, Living Table United Church of Christ (USA)

Rev. Gregory Seal Livingston, Syria Faith Initiative, NYC (USA)

Riccardo Bella, Theater Technician, Milan (Italy)

Riccardo Bellofiore, former professor of political economy, University of Bergamo (Italy)

Riccardo Cristiano, President of the Association of Journalists, friends of Father Dall’Oglio (Italy)

Richard Atkinson Chester (UK)

Richard Greeman, Victor Serge Foundation (France)

Richard Kuper, activist/educator, London (UK)

Richard Wood, Retired Chair, Sociology Department, DeAnza College (USA)

Rima Anabtawi, M.A. Groves, TX (USA)

Rima Majed, Assistant Professor, American University of Beirut (Lebanon)

Roane Carey, Senior Editor, The Nation (USA)

Robert Brenner, Center for Social Theory and Comparative History, UCLA (USA)

Robert Day, Southfield, MI (USA)

Robert Evans, Erie, PA (USA)

Robert Green, Hackney (UK)

Robert J. Pechacek, Woodstock, IL (USA)

Roberto Andervill, Social Worker & Activist (Italy)

Roger Silverman, former candidate, British Labour Party National Executive Committee (UK)

Rohini Hensman, Writer and Independent Scholar (India)

Roland Merieux, Member of the National Animation Team of ENSEMBLE! (France)

Romolo Molo, Lawyer (Switzerland)

Ronald Souza, Dallas, US (USA)

Ronnie Herbolzheimer, Leibnitz (Austria)

Rosanne S, Durban (South Africa)

Roseline Vachetta, former European MEP, New Anti-Capitalist Party (France)

Rosita Di Peri, professor at the University of Turin (Italy)

Ruairi Nolan, Exeter (UK)

Rupert Read, Philosopher, University of East Anglia (UK)

Ruth Riegler Glasgow (UK)

S Ghazal, Baildon (UK)

Saajeda Bayat, Businesswoman (South Africa)

Sadri Khiari, designer (Tunisia)

Saeb Shoufi, Fort Worth TX (USA)

Saffo Papantonopoulou, Tucson, AZ (USA)

sagawa toshiaki, Japan

Salim Sendiane, Angers (France)

Salima Bey, Paris (France)

Salwa Ismail, Professor of Politics, SOAS, University of London (UK)

Sam Friedman, Poet and AIDS researcher (USA)

Sam Hamad, Writer & Researcher, University of Glasgow (Scotland)

Samantha Falciatori, Web Author (Italy)

Samia Akkad, Rome (Italy)

Samuel Farber, Professor Emeritus of Political Science, Brooklyn College of CUNY (USA)

Sandra Bender, researcher & human rights activist (USA)

Sandra Hetzl, Translator and Curator (Germany)

Sara Abbas, PhD Candidate, Freie Universität, Berlin (Germany)

Sara Lucaroni, journalist (Italy)

Sascha Ruppert-Karakas, Munich (Germany)

Saskia Sassen, Professor, Columbia University, New York City (USA)

Scott Lucas, Editor, EA WorldView & Emeritus Professor, University of Birmingham (UK)

Scott Tokaryk, Berlin (Germany)

Sébastien Guex, Professor, University of Lausanne & Former Member, City Council of Lausanne (Switzerland)

Seda Altuğ, Academic, Istanbul (Turkey)

Sergio Bellavita, trade unionist (Italy)

Sergio Viña, Valencia (Spain)

Sevgi Dogan, Professor, Scuola Normale Superiore (Italy)

Seyla Benhabib, Eugene Meyer Professor of Political Science & Philosophy Emerita, Yale University (USA)

Shafie Chkair, Kuwait (Kuwait)

Shakuntala Banaji, LSE, University of London, (UK)

Shayna Silverstein, Chicago, IL (USA)

Sheriff Tabba, Montréal (Canada)

Sherry Wolf, author/trade unionist, member, Tempest Collective, New York City (USA)

Shintaro Mori, translator (Japan)

Shireen Akram-Boshar, Democratic Socialists of America (USA)

Shirin Hakim, PhD Candidate at Imperial College London (UK)

Silvia Carenzi, PhD Candidate, Scuola Normale Superiore (Italy)

silvia carneiro Garcia, Lima (Peru)

Simon Assaf, Editor, al-Manshour, London/Beirut (UK/Lebanon)

Simon Pearson, Anti*Capitalist Resistance (UK)

Simona Arigoni, member of the cantonal parliament (Switzerland)

Simone Jeger (Switzerland)

Sina Zekavat, Global Prison Abolition Coalition (USA)

Siobhan O’Brien, Dublin (Ireland)

Sonali Kolhatkar, Multimedia Journalist (USA)

Songül Deniz (Germany)

Soraya Misleh, Journalist (Brazil)

Souad Labbize,, Toulouse ((France)

Stacy Brown, Director, Refugees Forward (USA)

Staffan Olofsson (Sweden)

Stanley Heller, Host, The Struggle Video News (USA)

Stefan Zgliczyński, Author and Publisher (Poland)

Stéfanie Prezioso, Academic, University of Lausanne & Member of the Swiss Parliament, Ensemble à Gauche (Switzerland)

Stephen Donahue, Toronto (Canada)

Stephen Hastings-King, PhD, writer, greater Boston (USA)

Stephen R. Shalom, William Paterson University, New Jersey (USA)

Stephen Soldz, Coalition for an Ethical Psychology (USA)

Stephen Zunes, Professor of Politics and International Studies, University of San Francisco (USA)

Steven Heydemann, Director, Program in Middle East Studies, Smith College (USA)

Subir Sinha, Senior Lecturer, SOAS, University of London (UK)

Sue Dalot, Bronx, NY (USA)

Sue Sparks, Unite (UK)

suha sibany, Paris (France)

Sukla Sen, Peace activist, (India)

Sumit Sarkar, Historian, (India)

Susan Nussbaum, Writer (USA)

Susan Smith, Muslim Peace Fellowship, Stony Point, NY (USA)

Susanna Sillanpää, Helsinki (Finland)

Suzi Weissman, Professor of Politics, Saint Mary’s College of California (USA)

Swati Birla, University of Massachusetts Amherst (USA)

Sylvia Arnstein, Champaign, IL (USA)

Tachibana Sara, Osaka-shi (Japan)

Talib Al Ali, Mississauga (Canada)

Tanika Sarkar, Historian, (India)

Tanya Monforte, DCL Candidate, McGill University (Canada)

Tasnim Sammak,, Palestinian, PhD Candidate, Melbourne ((Australia))

Tassos Anastassiadis, Journalist (Greece)

Terry Burke, Committee in Solidarity with the People of Syria — CISPOS (USA)

The Rev. David W. Good, Minister Emeritus, The First Congregational Church of Old Lyme, Connecticut (USA)

Theo Horesh, author and freelance journalist (USA)

Therese Rickman Bull, Independent Human Rights Upholder/Defender (USA)

Thomas Harrison, editorial board member, New Politics (USA)

Thomas Mansheim, Associate Professor Emeritus, St. Peter’s University (USA)

Tim Bates, Vinton, VA (USA)

Tim Hall, Communist Voice Organization USA)

Tim Leadbeater, Teacher (Aotearoa/New Zealand)

Timothy Gibran, Stockholm (Sweden)

Tory Whall, Salt Lake City, UT (USA)

Toufic Haddad, Academic and Author (Palestine)

Tristan Sloughter, Democratic Socialists of America, Larkspur, Colorado (USA)

Trond Revheim, Asker (Norway)

Vahid Yücesoy, PhD Candidate, University of Montreal (Canada)

Valerio Mattei, researcher and journalist (Italy)

Valerio Torre, lawyer, Revolutionary Marxist Collective “Assalto al cielo” (Italy)

Vicken Cheterian, University Lecturer in History & IR, University of Geneva, Webster University Geneva (Switzerland)

Vincent Bircher, trade union activist (Switzerland)

Vincent Commaret, Songwriter (France)

Vivek Sundara, Social activist, (India)

Vivian O’Dell, Research Scientist, University of Wisconsin Particle Astrophysics Center (USA)

Viviana Ferreras Lohe, Zamora (Spain)

W. J. T. Mitchell, Senior Editor, Critical Inquiry, Chicago (USA)

Walter Baldo C., Rproject.it (Italy)

Wasim Khalili Göteborg (Sweden)

Wayne Heimbach, Evanston, IL (USA)

Wendy Pearlman, Professor, Northwestern University (USA)

William Flesch, Waltham, MA (USA)

Yamazaki Hideki, Tokyo, Japan

Yasmin Fedda, filmmaker and artist (UK)

Yossi Bartal, Writer (Germany)

Younes Ajarrai, Caen (Morocco)

Zeenat Adam, International Relations Strategist, Stop the Bombing Campaign (South Africa)

Zhaleh Sahand, Houston, TX (USA)

Ziad Elmarsafy, Professor of Comparative Literature, King’s College London (UK)

Ziad Majed, Associate Professor, the American University of Paris (Lebanon/France)

Zulekha Dinath, Author (South Africa)

[list updated 19 April 2021]

To add your signature, send name, affiliation (for identification purposes only), country, and whether you are Syrian, with the subject line “Add name” here.

The logic of “the enemy of my enemy is my friend” is a recipe for empty cynicism.

The logic of “the enemy of my enemy is my friend” is a recipe for empty cynicism.

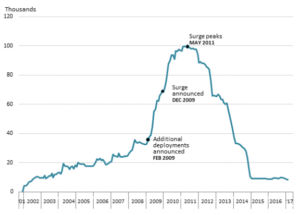

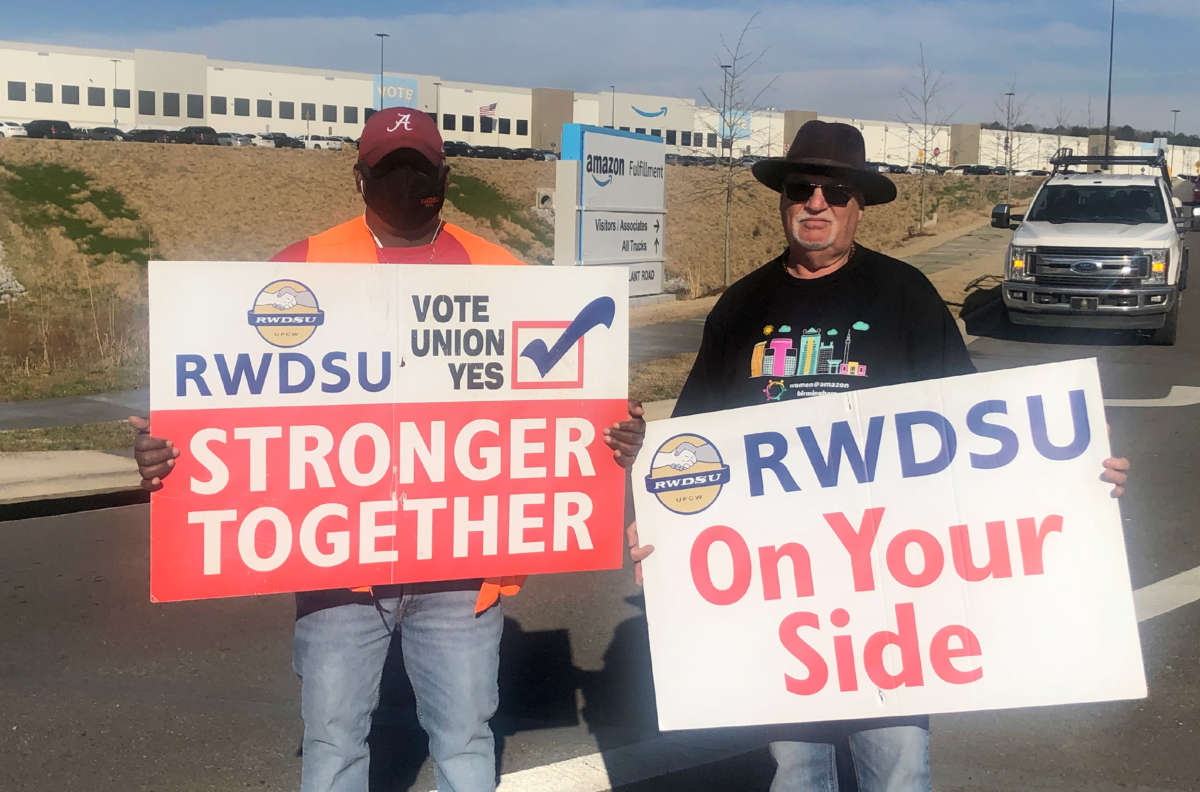

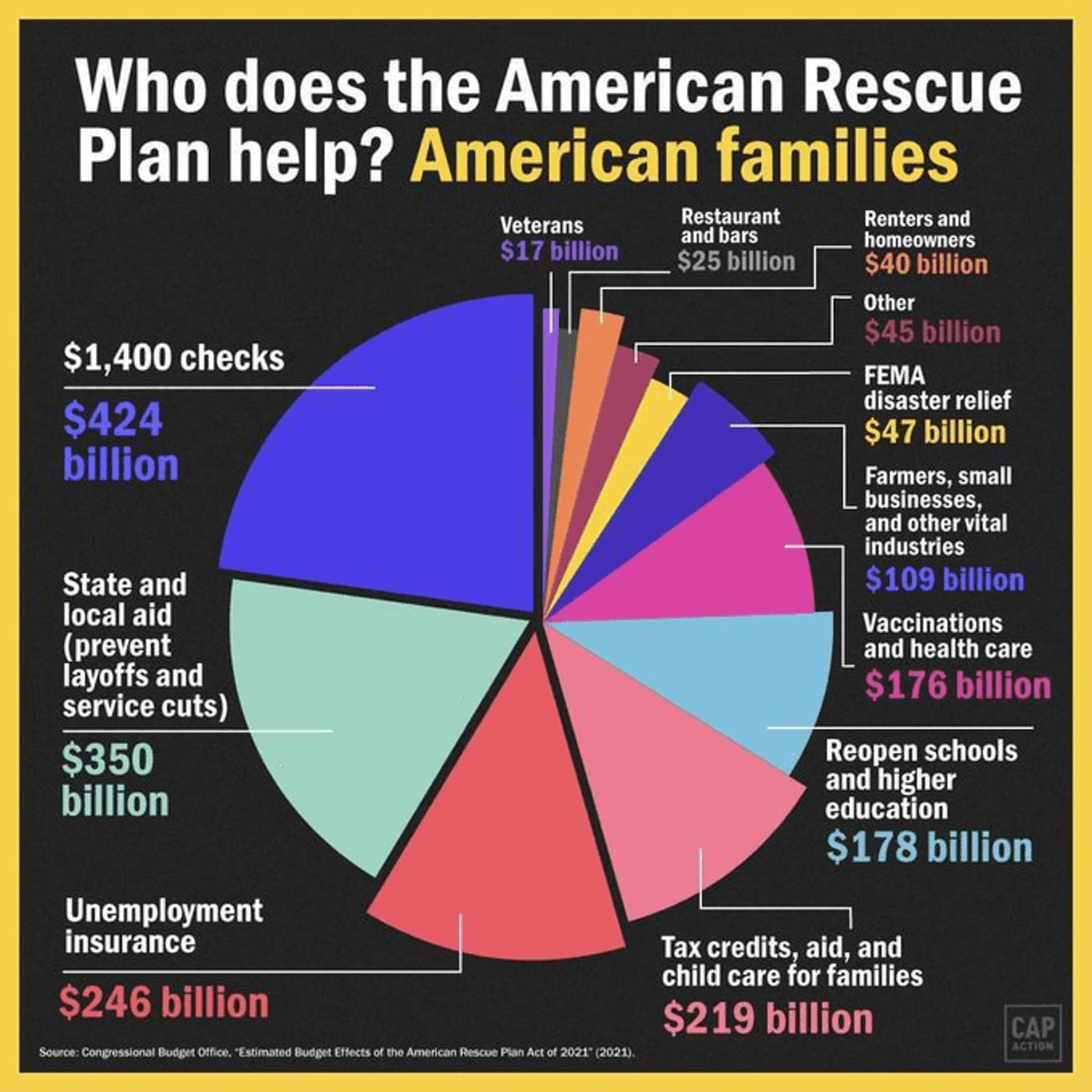

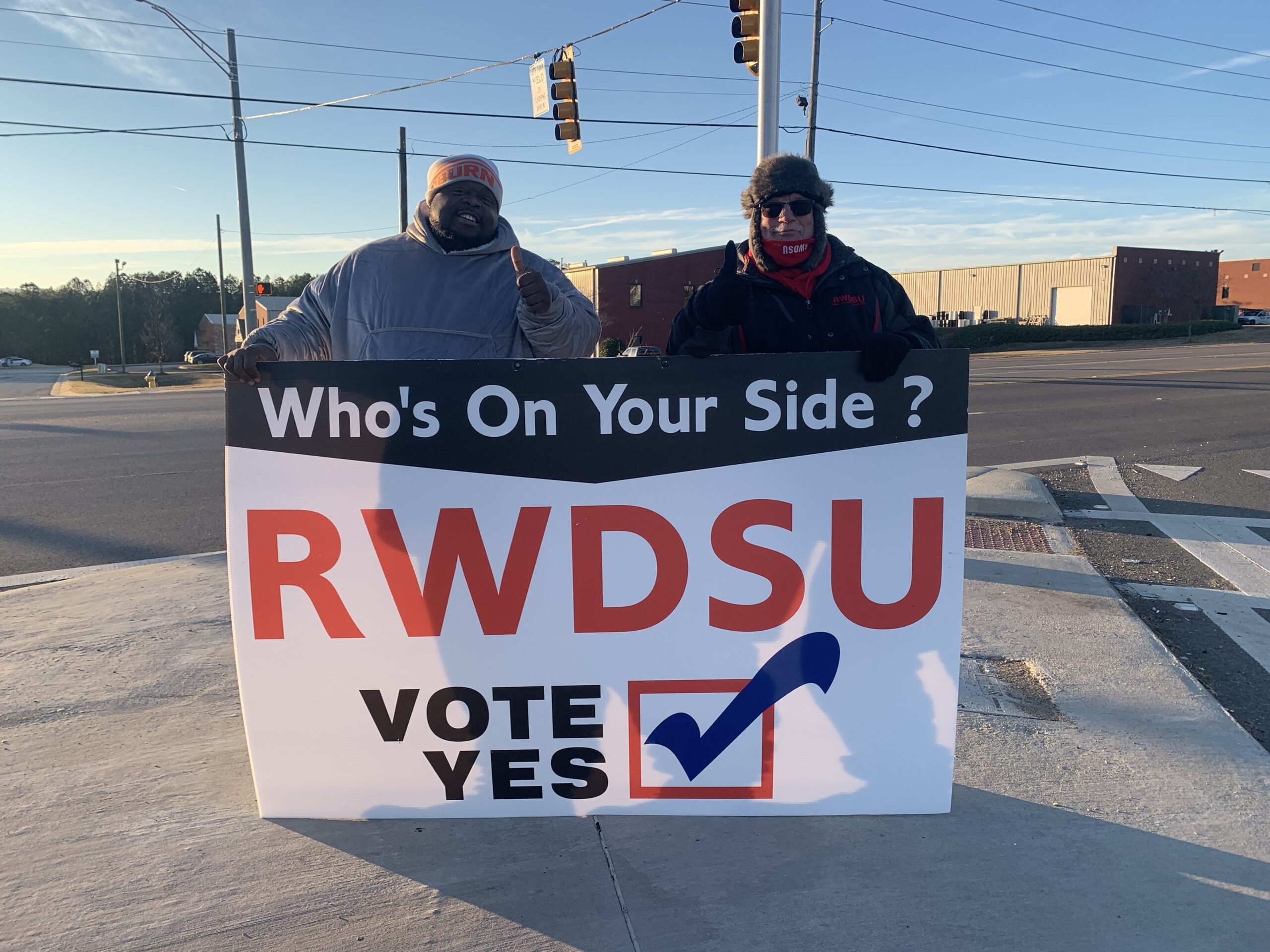

First, we must recognize that the overwhelming vote against the union in Bessemer marks a decisive defeat, not to be under estimated. It will undoubtedly have a dampening effect on other workers, especially given its broad media attention, and the high expectations of many.

First, we must recognize that the overwhelming vote against the union in Bessemer marks a decisive defeat, not to be under estimated. It will undoubtedly have a dampening effect on other workers, especially given its broad media attention, and the high expectations of many. The logistics industry, however, is doing well, especially during the pandemic. It is central, not just to retail (as with Amazon and Walmart), but also more importantly to global, just in time, manufacturing. So, it is an important arena where workers, if they organized on a broad scale, could potentially have, a great deal of leverage, what I call in my recent book (

The logistics industry, however, is doing well, especially during the pandemic. It is central, not just to retail (as with Amazon and Walmart), but also more importantly to global, just in time, manufacturing. So, it is an important arena where workers, if they organized on a broad scale, could potentially have, a great deal of leverage, what I call in my recent book (

This article was written for L’Anticapitaliste, the weekly newspaper of the New Anticapitalist Party (NPA) of France.

This article was written for L’Anticapitaliste, the weekly newspaper of the New Anticapitalist Party (NPA) of France.

[Editors’ note: This posting is adapted from invited remarks at the American Educational Research Association, April 11, 2021 joint session of the Special Interest Groups on Freire and Marxism.]

[Editors’ note: This posting is adapted from invited remarks at the American Educational Research Association, April 11, 2021 joint session of the Special Interest Groups on Freire and Marxism.]

“My biggest weakness was not finding the mettle to remain alone… without any connections, attachments, relationships at all. That is the source of all the misery.” —Nora Bossong, Gramsci’s Fall.

“My biggest weakness was not finding the mettle to remain alone… without any connections, attachments, relationships at all. That is the source of all the misery.” —Nora Bossong, Gramsci’s Fall.

Author’s Note – This article originally appeared in Spanish in La Joven Cuba (Young Cuba), one of the most important critical blogs in the island, where the Internet remains the principal vehicle for critical opinion because the government has not yet succeeded in controlling it. The article elicited some strong reactions including that of a former government minister who called it a provocation.

Author’s Note – This article originally appeared in Spanish in La Joven Cuba (Young Cuba), one of the most important critical blogs in the island, where the Internet remains the principal vehicle for critical opinion because the government has not yet succeeded in controlling it. The article elicited some strong reactions including that of a former government minister who called it a provocation.

This article was written for L’Anticapitaliste, the weekly newspaper of the New Anticapitalist Party (NPA) of France.

This article was written for L’Anticapitaliste, the weekly newspaper of the New Anticapitalist Party (NPA) of France.

The new US president Joe Biden recently announced his intention to convene a “Summit for Democracy” with the aim of reuniting the West—this time, above all against China. The European Commission, for its part, already classified China as a “systemic rival” in 2019. These moves represent active efforts to re-establish the fundamental liberal anti-communist consensus as the West’s common creed. This anti-communism constitutes the core of the West’s hubris, as was recently

The new US president Joe Biden recently announced his intention to convene a “Summit for Democracy” with the aim of reuniting the West—this time, above all against China. The European Commission, for its part, already classified China as a “systemic rival” in 2019. These moves represent active efforts to re-establish the fundamental liberal anti-communist consensus as the West’s common creed. This anti-communism constitutes the core of the West’s hubris, as was recently

Disreputable writers and outlets, often operating under the aegis of “independent journalism” with purportedly “leftwing” views, are spreading corrosive propaganda and disinformation that aims to strip Syrians of political agency

Disreputable writers and outlets, often operating under the aegis of “independent journalism” with purportedly “leftwing” views, are spreading corrosive propaganda and disinformation that aims to strip Syrians of political agency

Lois Weiner

Lois Weiner

In a world based on exploitation and oppression, resistance is ever present. Most of the time it simmers below the surface but sometimes it takes the form of huge social explosions. It would seem natural for those on the left to wish for such mass resistance to occur on a truly global scale. There is, however, a complicating factor. A section of the left has embraced a ‘campist’ view, in some ways a hangover from the Cold War period, that sees global politics primarily in terms of a conflict between a US led predatory group of countries and another

In a world based on exploitation and oppression, resistance is ever present. Most of the time it simmers below the surface but sometimes it takes the form of huge social explosions. It would seem natural for those on the left to wish for such mass resistance to occur on a truly global scale. There is, however, a complicating factor. A section of the left has embraced a ‘campist’ view, in some ways a hangover from the Cold War period, that sees global politics primarily in terms of a conflict between a US led predatory group of countries and another

This article was written for L’Anticapitaliste, the weekly newspaper of the New Anticapitalist Party (NPA) of France.

This article was written for L’Anticapitaliste, the weekly newspaper of the New Anticapitalist Party (NPA) of France.

In his book Capital in the Twenty-First Century,

In his book Capital in the Twenty-First Century,

This article was written for L’Anticapitaliste, the weekly newspaper of the New Anticapitalist Party (NPA) of France.

This article was written for L’Anticapitaliste, the weekly newspaper of the New Anticapitalist Party (NPA) of France.

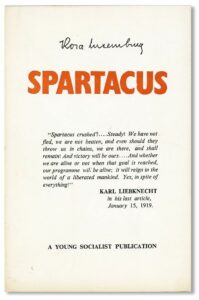

Rosa Luxemburg, the Polish-born revolutionary of Jewish heritage who was born 150 years ago on March 5th this year, had no reason in her frenetic political, intellectual and literary activism to attend to an inconsequential island in the Indian Ocean.

Rosa Luxemburg, the Polish-born revolutionary of Jewish heritage who was born 150 years ago on March 5th this year, had no reason in her frenetic political, intellectual and literary activism to attend to an inconsequential island in the Indian Ocean.