Rosa Luxemburg and the ‘Young Socialist’ of Ceylon (Sri Lanka)

Rosa Luxemburg, the Polish-born revolutionary of Jewish heritage who was born 150 years ago on March 5th this year, had no reason in her frenetic political, intellectual and literary activism to attend to an inconsequential island in the Indian Ocean.

Rosa Luxemburg, the Polish-born revolutionary of Jewish heritage who was born 150 years ago on March 5th this year, had no reason in her frenetic political, intellectual and literary activism to attend to an inconsequential island in the Indian Ocean.

However, decades after her murder in Berlin on 15th January 1919, Ceylon (renamed Sri Lanka in 1972) would become “a chief outlet, for a little while, of Luxemburg’s pamphlets in the English language”, as Paul Buhle observes in his Afterword to Kate Evans’ marvelous graphic biography Red Rosa.

Rosa Luxemburg’s polemics on socialist transformation in conditions of capitalist development, militarism and imperialism, and the institutionalization of trade unions and political parties of the working class – in debate with leading personalities of the European socialist movement including Eduard Bernstein, Karl Kautsky and V. I. Lenin – were originally written in German between 1898 and 1918.

As Norman Geras commented: “The diagnosis of the tendencies of capitalist development and the articulation to it of a strategy for socialism; the nature of revolutions outside the advanced capitalist countries and the relationship of democratic to socialist tasks; the place of extra-parliamentary, mass struggle in the battle for socialism; the nature of socialist democracy …” are questions she opened.

After her tragic death at 47 years of age, the authority of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU), victorious unlike its German comrades in the overthrow of the old order and endowed with state power, contributed to the suppression of the circulation of her writings, particularly where critical of Bolshevik viewpoints.

Later, Joseph Stalin’s pronouncement in 1931 that Rosa Luxemburg was a co-author of the “utopian … schema of the permanent revolution” – diametrically opposed to his perspective of constructing socialism in one country, beginning with the Soviet Union – signaled to Communists everywhere that she was an implacable foe.

It was up to independent Marxists and dissident Communists, who did not enjoy the resources and patronage extended to the Moscow-based Progress Publishers and Foreign Languages Publishing House that published Marx and Engels, Lenin and Stalin, in many languages, to translate, print and distribute her writings in constrained circumstances.

The Russian revolutionary Leon Trotsky admired Rosa Luxemburg, and defended her against political slander by Stalin. His supporters in New York began carrying translations of her articles in their journals, the New International succeeded by The Fourth International. These publications traveled, sometimes as contraband during the Second World War, wherever there were contacts with other Trotskyists.

Odd corners

One of the “oddest” of the “odd corners”, as Buhle justifiably remarks, which publicized Rosa Luxemburg to Anglophone Marxists in the 1960s and 1970s, was Ceylon.

In the mid-1930s in a British imperial possession, a group of young radical men and women formed the Lanka Sama Samaja Party (LSSP), subsequently an affiliate of Trotsky’s ‘World Party of Socialist Revolution’, the Fourth International.

It campaigned for workers and peasants’ rights and against colonialism and imperialism, amidst repression and imprisonment by the colonial state, investing a small party with societal respect and trade union support disproportionate to size (never more than 1000 before 1970).

From 1950 onwards, the LSSP had an active publications program printing pamphlets and short books by Leon Trotsky; in contest with the Ceylon Communist Party (CCP) for hegemony on the Left in the workers’ movement and electoral politics.

However, all the quotes from Trotsky were no defense to the LSSP’s embrace of reformism. To borrow from Luxemburg (writing in 1904 with reference to the German Social Democratic Party—SPD): the “…tendency in the party to regard parliamentary tactics as the immutable and specific tactics of socialist activity” became pre-eminent.

The LSSP adapted to the long-standing perspective of the CCP on the need for an alliance between the Left and the ‘progressive national capitalist’ Sri Lanka Freedom Party (SLFP) against the ‘reactionary comprador capitalist’ United National Party and imperialism (symbolized by the presence of British military bases and US oil companies). In 1960, the LSSP and the CP separately entered into no-contest and mutual support pacts with the SLFP. Four years later, both Left Parties joined a popular front government led by the SLFP. Once described as a tactic by the leadership of the ‘Old Left’, it is to the present day their staunch strategy, except now only as pitiful leftovers from the past.

By 1961, some on the LSSP Left began publishing a non-party journal called Young Socialist, its name inspired no doubt by the newly formed youth organizations of the US Socialist Workers Party and the British Labour Party (in which the Trotskyist Socialist Labour League was active). They assumed their audience to be the Youth Leagues of the LSSP, which is how sympathizers and candidate members of the Party were organized.

Its first editorial explained that there was much talk of socialism in Ceylon but no clarity on what it meant. “ … what are the essential foundations and features of such a [socialist] society and how can they be laid and developed? Indeed, what precisely is the nature and organization of the society in which we live and which we seek to change?”

The co-editors were May Wickremasuriya and Sydney Wanasinghe, occasionally joined by Osmund Jayaratne, R. S. Baghavan and Wilfred Pereira. The journal folded in 1970 as its supporters went their separate ways. A revival in 1980 only managed to put out two issues. Rosa Luxemburg’s essay on The Progress and Stagnation of Marxism (1903), translated by Eden and Cedar Paul, was to appear in its pages in 1967.

The animator of the Young Socialist was the indefatigable Sydney Wanasinghe. In addition to the magazine, he issued pamphlets by Trotsky including the out-of-print English translation of The War and The International (1915/1971). Wanasinghe was also the local distributor of Pioneer Press, Monthly Review Press and Merlin Press books. He founded the Suriya Bookshop in 1964, which he ran until near his death in 2007, mostly out of his home.

Among the titles sold by him was Rosa Luxemburg’s The Accumulation of Capital (1913/1951), subtitled ‘A Contribution to an Economic Explanation of Imperialism’ and translated by Agnes Schwarzschild; with an introduction by the British left-wing economist Joan Robinson who visited Ceylon in 1958 to advise the government’s Planning Secretariat.

Dissemination

However, Wanasinghe’s main involvement in the dissemination of Rosa Luxemburg’s writing outside of Sri Lanka, was to publish what remain her best-known writings in the portable pamphlet form.

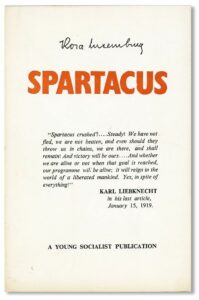

Socialism and the Churches (1905) was issued in 1964, based on the translation by Socialist Review (Birmingham, England). The Mass Strike, The Political Party and The Trade Unions (1906) appeared in 1964, as translated by Patrick Lavin. Social Reform or Revolution (1900) was released in 1966, from the translation by the anonymous Integer. Spartacus (1918) appeared in 1966, as translated by Eden and Cedar Paul. ‘The Crisis in the German Social Democracy’ better known as ‘The Junius Pamphlet’ (1915) followed in 1967, based on the translation by the New York-based Socialist Publication Society. What is Economics? (1954) was released in 1968, as translated by Theodore Edwards (pseudonym of Edmond Kovacs).

What is missing from this list are two of her important contributions to revolutionary theory: Organizational Question of Social Democracy (1904) and The Russian Revolution (1918). Neither of these texts were published by the US Trotskyists who were the primary source of the English-language translations relied upon by Sydney Wanasinghe, until 1970. Both articles were under copyright having been published by the University of Michigan Press in 1961, as The Russian Revolution and Leninism or Marxism?, based on Bertram D. Wolfe’s 1940 translation in the Workers Age newspaper.

Nevertheless, both in the US and Ceylon, there must have been discomfort in Luxemburg’s critique of the Bolshevik organizational model valorized by Trotskyists; and on the first steps of the Russian Revolution under Lenin’s leadership. In her estimation, and affected by the 1905 revolution in Russia, it was not the leaders and leading bodies of socialist parties, but the “great, creative acts of the often spontaneous class struggle seeking its way forward” that rightly shaped the policy of the socialist movement.

Her prescient warning to the Bolsheviks on the dangers of an ultra-centralized party (conditioned of course by illegality and tsarist persecution), which she argued concentrated power in the ‘intellectuals’ staffing its highest administrative structures haunt us still. “Historically, the errors committed by a truly revolutionary movement are infinitely more fruitful than the infallibility of the cleverest Central Committee”.

Years later in 1918, writing from a German prison cell, Luxemburg hailed the party of Lenin as the only one which by its demand – ‘All power in the hands of the proletariat and peasantry’ – took the Russian revolutionary movement forward towards socialism. Welcoming the October 1917 uprising, she nonetheless cautioned the Bolsheviks against counter-posing the ‘dictatorship of the proletariat’ with ‘democracy’.

Socialist democracy

“Socialist democracy begins simultaneously with the beginnings of the destruction of class rule and of the construction of socialism. It begins at the very moment of the seizure of power by the socialist party. It is the same thing as the dictatorship of the proletariat”.

She insisted that, “Freedom only for the supporters of the government, only for the members of one party—however numerous they may be—is no freedom at all. Freedom is always and exclusively freedom for the one who thinks differently … Without general elections, without unrestricted freedom of press and assembly, without a free struggle of opinion, life dies out in every public institution, and becomes a mere semblance of life in which only the bureaucracy remains as the active element.”

The intention here is not to disown Lenin in order to deify Luxemburg. It is instead, as she demonstrated by example, to have a critical appreciation of socialist theory and praxis. Any renewal of the socialist project in the 21st century must assimilate her insights on democracy and freedom as both means and end.

Through her experiences in the class struggle and socialist movement, her theorization explain why and how the individual event or isolated fact must be interpreted in relation to the social whole of (capitalist) development. We learn from her that to be opposed to reformism, is not the same as being opposed to social and democratic reforms. She explained that the economic crises of capitalism are no guarantee that the alternative will not be an even more horrific barbarism, without the conscious actions of the exploited and oppressed for a better world.

So much for the role of the Young Socialist in the production and dissemination of Rosa Luxemburg’s writings in English, in a genuinely internationalist undertaking. What of their reception in Ceylon/Sri Lanka? That tale must wait another time. For now, on this 150th anniversary of her birth, it is enough to apply her epitaph on the lost revolution in Germany to herself: “I was, I am, I shall be!”