Refusal Music

It is truly remarkable that, after everything this world has seen over the past year, we still hear so much about “the power of positivity.” A pandemic continues to kill thousands each day, government after government bungling the roll-out of the vaccine. The Arctic melts, wildfires destroy whole countries. Heroes and friends are dead, enemies are in power.

It is truly remarkable that, after everything this world has seen over the past year, we still hear so much about “the power of positivity.” A pandemic continues to kill thousands each day, government after government bungling the roll-out of the vaccine. The Arctic melts, wildfires destroy whole countries. Heroes and friends are dead, enemies are in power.

And yet, to hear the speeches of self-help gurus and chipper morning show hosts, we needn’t fret. Movies and television shows present us with neat and symmetrical narratives, teaching us to ignore messiness and ambiguity. Well-meaning liberals proclaim the chaos over.

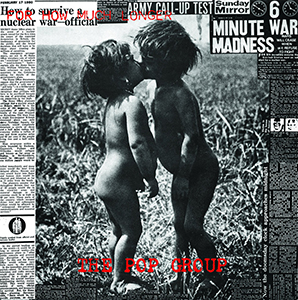

Four years ago, not long before Donald Trump’s inauguration, and a few days after hearing the much-mourned cultural critic Mark Fisher had died, I re-read an article he wrote in 2016 about the reissue of the Pop Group’s 1980 album For How Much Longer Do We Tolerate Mass Murder? Fisher’s description of this magnificent piece of industrial punk-funk is prescient:

While dominant ideology sought to naturalise and neutralise drudgery, atrocities and exploitation, The Pop Group aimed to do the opposite: to bring suffering and systemic violence to the screaming forefront of consciousness. This wasn’t simply a matter of reciting facts, but of emotional engineering, a jolting out of the ideological trance that accepts injustice as inevitable. Mark Stewart’s vocals perform this maladjustment, this refusal to treat the excesses of global capitalism as anything but insane.

These were the earliest years of neoliberalism’s dominance. Thatcher had been elected the previous spring, and Reagan was well on his way to victory in the US. On top of their outward viciousness toward anything smacking of unions, social movements, or social welfare, their politics sought to atomize, isolate, to emotionally content working people with misery.

Music such as the Pop Group’s could never, as Fisher points out, simply recite facts. People knew the facts. The trick was to force the audience to psychologically come to grips with the possibility of refusal. “[T]he album is best seen,” he wrote, “as part of a struggle against the new ‘common sense’ that capital was seeking to impose in the early 1980s using techniques of reality- and libidinal-engineering (PR, branding and advertising).”

The Pop Group were far from the first in the punk milieu (including the “post” and “proto” varieties) to tap into this mode of expression. Contemporaries such as Gang of Four, Delta 5, Au Pairs each sought to struggle against the straitjacket of late capitalism in their own way. In fact, a simple map of associations and collaborations reveals “refusal” as not just a theme but a thorough structure of feeling for the era’s most original music.

After the Pop Group’s initial demise, Mark Stewart went onto several collaborations with producer Adrian Sherwood. The end results were a kind of dub music for the middle apocalypse: dark, manic, thick and jagged, like rebar in concrete. Sherwood’s own work with the tragically underrated TACK>>HEAD point to these experiments as not only seminal to what would come to be known as “industrial music” but its neglected cousin of “industrial hip-hop.” Groups like Consolidated, Beatnigs and Disposable Heroes of Hiphoprisy came to claim the mantle, mixing militant lyrics with razor-on-metal production. For a brief time, before the slowed-down R&B-influenced “west coast sound” became so hegemonic, artists toying with the sounds of industrial destruction – think Terminator X era Public Enemy – were at the vanguard of hip-hop.

Then there were the sound’s more obviously danceable iterations, taking over abandoned warehouses for all-night raves in Detroit, Chicago, Berlin, London and beyond. This act of reclamation was naturally rejected by the forces of the neoliberal city. When British ravers fought back against Thatcher’s attempts to quash their subculture, they weren’t just doing to because of their love of beats but because their vision of space was one that felt freer, saner, more equitable.

This is different than what we might blandly refer to as “protest music,” the use of song to decry this or that specific issue. There were plenty of those too, including from the artists above. But even those who focused on the single issue did so in a way that used it as synecdoche, one cog of many on a carriage careening off a cliff. In both content and form, these genres, artists, and songs sought to expose the deep-seated malfunction at society’s core. They sounded like the madness that was gripping daily life underneath its saccharine shell, centering decay while defiantly refusing to take the blame for it. Crossovers between punk and hip-hop, noise and dance, were not epiphenomenal to collective refusal. On the contrary, they were drawn together by a common utopian negation.

It would be glib to say that this kind of music was “revived” during the Trump years. What can be said is that the fact of apocalypse is now undeniable. In this context, music that seizes the madness is more prescient than it has been for some time. The noisier sides of hip-hop and spoken word – artists like clipping, Death Grips and Moor Mother – have gained critical acclaim. Electronic and indie artists are also, in their own way, tapping into the extreme unpredictability and isolation, evidenced in songs like Parquet Courts’ “Violence,” Squid’s “Houseplants.” Even the overdone aesthetics of vaporwave offer a refusal of sorts, tongue-in-cheek though they may be.

What remains to be seen is whether these genres and artists will recognize themselves in each other. For it’s this kind of polyvalent cultural expression – one that rejects isolation, alienation, and anodyne notions of artistic convention – that is needed to push back against the madness. Refusal, in the sense we mean it here, must be more than a collection of incidents. It needs to grow and flourish and morph into an unstoppable idea around which people can reimagine their lives. We likely won’t know what shape this can take until it is safe to go outside again, safe to gather in mass numbers for any kind of cultural expression. But the raw materials are there.

This article originally appeared in the German publication Melodie & Rhythmus.