Israeli Jews and Palestinians protest apartheid in Tel Aviv. (Oren Ziv, +972 Mag)

More than six thousand Israeli Jews and Palestinians assemble in Tel Aviv, waving Palestinian flags and denouncing Israeli policy as apartheid. Thousands of young Ethiopian-Israelis march against police brutality, blocking highways, even throwing stones at police, and some chanting, “Free Palestine.” Mizrahi Jews petition Israel’s High Court to reject the Nation-State Law as anti-Arab and therefore both anti-Palestinian and anti-Mizrahi. An increase in draft-dodging leads Israel’s army to lament a “decreased motivation to serve” among the population.

Such incidents from the last couple years remain absent from Haymarket’s anthology Palestine: A Socialist Introduction, published in December 2020, and from Steve Leigh’s review published late last month in New Politics. The book’s section titled “Workers of the World Unite” does not invite masses of Israeli Jewish workers to join the Palestinian liberation struggle. In fact, one of the book’s contributors, Daphna Thier, even declares the Israeli working class “Not an Ally.” Likewise, Leigh insists that “the Israeli working class is not a potential revolutionary force.”

Thier, Leigh, and the Haymarket book’s editors Sumaya Awad and brian bean [spelled lower-case], all based in the United States like myself, come from a position I share, that of supporting the Boycott Divest Sanctions (BDS) movement as one component of democratizing the Middle East from below. Backed by 86% of Palestinians in the West Bank and Gaza Strip, BDS has been called a “strategic threat” by the Israeli establishment which has spent millions combating it. The anthology’s contributors, editors, and reviewer are right to insist that Israeli Jews’ present opposition to BDS is not sufficient reason for the world’s Left to stop supporting the movement and its demands for social equality. However, when they appear to altogether discount Israeli workers’ revolutionary potential, they overlook the importance of joint mass struggle between Palestinians and Israeli Jews.

Common Revolutionary Aims

Thier begins the chapter “Not an Ally” by summarizing the Marxist theorist Hal Draper’s argument that the working class generally has the “interest and ability to overthrow capitalism.” Nonetheless, Thier argues that the Israeli Jewish working class is “an exception to this rule” and is “incapable of solidarizing with Palestinians” due to “their material conditions.” It is unfortunate that the chapter does not mention what Draper wrote specifically about Israel. In 1954, Draper argued that Zionism went against ordinary Israeli Jews’ material self-interest and well-being.

A Zionist state “will be a hell for the Jews,” Draper argued, “as long as it insists on being a Jewish ghetto in an Arab world.” Therefore, Draper proposed that Jews and Arabs could engage in “joint struggle from below, cemented by common national-revolutionary aims and common social interests.” What Draper contended in 1954 is still true today; the reality is that the Zionist state has been a disaster for Israel’s Jews.

Zionism has enriched Israeli elites, but it has not liberated Israeli Jewry from financial precarity. Some 18% of Israeli Jews live below the poverty line. Despite the Israeli government’s frequent invocations of Holocaust history, even a quarter of Israel’s Holocaust survivors live in poverty. This impoverishment is connected to Israeli militarism. As Israeli refuseniks—who choose jail time over performing their mandatory military service—point out in their 2021 open letter, Israel’s high military and police spending takes away from funding on “welfare, education, and health.”

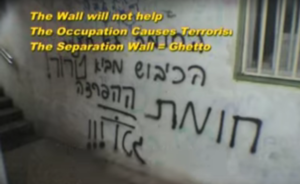

“The Occupation Causes Terrorism” graffiti (pictured in the documentary Anarchists Against the Wall of Israel by It’s All Lies Production)

Although Thier claims that Israel’s occupation of the West Bank and Gaza has been “beneficial to the Israeli capitalists, state, and workers,” the occupation has been the main cause of terrorist violence against ordinary Israelis. The West Bank settlements, consistently expanded throughout decades of Left and Right Zionist administrations alike, have been a common complaint in Hamas’s public statements. The repeated bombings of Gaza, also supported across Israel’s political establishment, have actually boosted popular Palestinian support for Hamas.

Overall, Zionism has failed to provide a situation of safety and well-being for Israeli Jews, creating instead what Draper called a “hell for the Jews.” The refuseniks’ letter declares that “Zionist policy” is “poisoning Israeli society–it is violent, militaristic, oppressive, and chauvinistic.” The endlessly militarized atmosphere has been a cause of major distress for Israeli teenagers, some 73% of whom report mental health problems. Increasing numbers of Israelis are discharged from the army due to mental illness. The age-adjusted suicide rate for Israeli Jews is 2.4 times higher than it is for Israeli-Palestinians.

Israel’s Mizrahi (ethnically Middle Eastern) Jews, who have faced persistent racism from Ashkenazi (ethnically European) Jews throughout Zionism’s history, have even more reason to support revolutionary change. Israeli Mizrahi scholar Smadar Lavie has gone so far as to describe “intra-Jewish apartheid” within Israel. Most infamously, Israeli authorities in the 1950s kidnapped Mizrahi children and gave at least some of them to Ashkenazi Jewish families to raise. As the New York Times reports, this horrific episode of Israeli history has been corroborated by DNA tests and acknowledged by an Israeli cabinet member.

Israeli Black Panthers hold a sign telling Prime Minister Golda Meir, “Fly away / We’ve had enough of you” (Electronic Intifada)

In downplaying Mizrahi Jews’ potential to turn against Zionism, Thier minimizes the powerful legacy of the Mizrahis’ 1970s group the Israeli Black Panthers. Thier writes that “they too subordinated the question of Zionism to the economic issues they faced.” In fact, as Jaclyn Ashly reports in Electronic Intifada, the Israeli Black Panthers “took a clear stand against Zionism.” Protesting the 1972 World Zionist Congress, the group believed that the “Zionist movement was the cause of their socioeconomic conditions in Israel.” They were the first Israelis to meet with the Palestine Liberation Organization.

“The Nature of a Settler Working Class”

In arguing that Israeli Jewish workers form a necessarily reactionary class, Thier and Leigh point out characteristics that also apply to U.S. non-Indigenous workers. Thier writes, “[I]t is the nature of a settler working class and its unique relationship to the state that distinguishes the Israeli proletariat from other working classes.” Leigh describes “the overwhelming privilege of the Israeli working class in relation to the Palestinians.” As these authors surely know, the U.S. working class is also settler-colonial and has overwhelming privilege in relation to Native Americans.

Sadly, despite the editors’ location in the United States, Native Americans are barely mentioned in Palestine: A Socialist Introduction and appear only twice in the index. One of these mentions correctly points out, “the Nakba [displacement of Palestinians] is reminiscent of the United States’ dispossession and erasure of indigenous Americans.” The United States has been more successful so far at eliminating the native population than Israel has, but does that somehow give U.S. workers more potential to be revolutionary?

Shrinking Indigenous lands in USA and Palestine (US Campaign for Palestinian Rights)

Leigh, Thier, Awad, and bean lack consistency when they deny the revolutionary potential of Israeli Jewish workers but advocate revolutionary class struggle here in the United States. In a previous New Politics article, Leigh wrote that Americans “need to stress both a united front approach and the need to build revolutionary organization.” Awad and bean title the book’s conclusion “Revolution Until Victory,” and they center U.S. workers in their proposed revolution. They even propose organizing American “workers involved directly or indirectly in the military industrial complex.” But when it comes to Israel, Thier writes, “Israeli workers are now rewarded through the arms economy.” If U.S. workers in the military-industrial complex can be revolutionaries, then why can’t Israeli Jewish workers in the military-industrial complex? And while Thier is right to criticize Israel’s 2011 tent protests for ignoring Palestinian rights, perhaps opposing it outright is a step too far. Didn’t our own Occupy Wall Street also fail, at least initially, to advance a decolonial platform? Didn’t the very name gloss over the fact that Wall Street existed on stolen Lenape territory? Living in somewhat of a glass house, U.S. leftists should be careful not to apply a standard to Israelis that we wouldn’t apply also to ourselves. Perhaps with a leftist intervention of critical support rather than dismissal, Israelis’ protests against elites could have developed robust demands for Palestinian freedom.

Draper wisely distinguished between anti-Zionism, which opposes a regime, and anti-Israelism, which opposes a country and its people. He compared being anti-Zionist to being anti-Soviet or anti-Nazi, whereas being anti-Israel is like being anti-Russia or anti-Germany. Unfortunately, some in the Palestine solidarity movement conflate anti-Zionism and anti-Israelism. Anti-Israelism is Roger Waters conjuring up a false story about Israeli concert attendees failing to applaud his call for regional peace. Anti-Israelism is the now-defunct Socialist Worker (then affiliated with Haymarket) declaring “unconditional” support for Hamas, a far-right group that intentionally kills Israeli civilians. Anti-Israelism is Judith Butler bizarrely remarking, “Yes, understanding Hamas, Hezbollah as social movements that are progressive, that are on the Left, that are part of a global Left, is extremely important.” Maybe more Israeli Jews would join the global Left if they felt as invited as their theocratic enemies are.

Joint Struggle Against False Consciousness

To be fair, the Haymarket anthology is correct that Israeli Jews presently exhibit shockingly high levels of anti-Arab racism. Polls report that about 90% of Israeli Jews would be disturbed if their child befriended an Arab of the opposite sex, and about 80% think Jews should get preferential treatment over non-Jews. In both the Israeli and U.S. cases, racist nationalism can be a powerful form of false consciousness. “Since we can remember, we have been brainwashed with hatred and fear of our Palestinian neighbors,” the Israeli group Anarchists Against the Wall declared in 2004. Similar mechanisms have taken place in the United States, with Indigenous people denigrated as “savages” and “red—ns” and demeaned through sports logos and mascots across the country. Although opinions are shifting, there continues to be widespread support among U.S. workers for celebrating Columbus Day and for building dirty energy projects that further encroach on Indigenous communities’ lands.

“Return Serve,” a photograph by Hamde Abu Rahma, from a 2013 art show benefiting Anarchists Against the Wall (Crimethinc)

Whether in the United States or Israel, the best way to break through false consciousness is, as Draper suggested, through “joint struggle from below.” During years of high-profile Indigenous-led joint direct action against the Keystone XL and Dakota Access pipelines, between 2012 and 2017, the percentage of Americans opposing these pipelines doubled, from 23 to 48 percent. Starting in 2003, there were militant joint Palestinian and Israeli direct actions blocking construction of the Separation Barrier. In the first three years of these protests, Israeli opposition to the wall in principle (not just to the wall’s route) also roughly doubled, from 7 to 13 percent. While that growth may not seem like much, it was large in proportion to the number of Israelis who took part in the protests, and it pointed a powerful strategic path forward. Joint struggle proved sufficiently impactful, Israeli activist Uri Gordon explains, that even more moderate Israeli peace groups began adopting the strategy and seeking out Palestinian partners.

If Thier is right that the anti-Zionist Israeli Black Panthers were “more brutally and violently suppressed than any other social justice movement in Israeli history,” then it demonstrates how much of a threat Israel considered joint struggle to be. Chicago’s Black Panthers also faced swift repression, including assassinations, after they tried building a Rainbow Coalition with Indigenous, Puerto Rican, and white radicals. By disrupting elites’ divide-and-conquer tactics, coalitions between the Israeli Panthers and the PLO, and between the U.S. Panthers and the American Indian Movement among other groups, posed a significant threat to the status quo.

Although the current number of Israeli Jewish BDS supporters is apparently only a couple hundred, and although Israeli Jewish support for a shared, democratic country is shrinking, down from 19% in 2018 to 10% in 2020, this could change. Anarchists Against the Wall activist Yossi Bartal explains that, “In such a blatantly racist atmosphere, the most radical act is to break this separation by demonstrating together with Palestinians, living together, talking to each other, loving and caring for each other–even making love with each other.” Jointly organized direct action helps tear down walls, physical and mental, between the two populations. By struggling together, the two groups can demonstrate—to each other, themselves, the world—a capacity to share a country.

Israel is not a hell for Jews.

The World Happiness Report 2020 ranks 156 countries by how happy their citizens perceive themselves to be, according to their evaluations of their own lives.

#The Top 20 happiest countries include:

Finland

Denmark

Switzerland

Iceland

Norway

The Netherlands

Sweden

New Zealand

Luxembourg

Austria

Canada

Australia

UK

Israel

Costa Rica

Ireland

Germany

US

Czech Republic

Belgium

There were maybe 60,000 Jews in Palestine in 1917 and there are over 6,000,000 today, with a high birth rate.

The fact that Jews were so unhappy elsewhere in the world, due to anti-semitism, is what drew them to Israel.

From 2006 to 2016, more Israelis left the country, long-term and permanently, than returned. Newsweek reported in 2018 on Israelis’ reasons for leaving Israel:

“Israel has one of the highest poverty rates and levels of income inequality in the Western world. Meanwhile, it also has one of the highest costs of living. Tel Aviv ranks ninth among the world’s most expensive cities, higher than New York and Los Angeles; five years ago, it ranked 34th. The situation is so dire that a 2013 survey by the financial newspaper Calcalist (the most recent Israeli study conducted on this topic) found that 87 percent of adults—many with children of their own—depend on substantial financial support from their parents.”

“Another reason many Israelis give for leaving is what they view as the country’s turn away from its origins as a secular Jewish democracy.”

“‘Half the kids in Israel are getting a Third World education,’ says Ben-David, citing data collected by his organization, the Shoresh Institution.”

Sources:

“Stats show more Israelis leave country than return,” YNet, 17 August 2018.

“More Israelis Are Moving to the U.S.—and Staying for Good,” Newsweek, 10 May 2018.

From Wikipedia: “Israel’s standard of living is significantly higher than that of most other countries in the region and is comparable to that of other highly developed countries. Israel was ranked 19th on the 2016 UN Human Development Index, indicating “very high” development. It is considered a high-income country by the World Bank.”

If Israel is hell for its Jews, what word would you to use to describe the condition of Palestinians in the occupied territories? Don’t be silly.

Further when and where have the Palestinians made a cogent appeal to the Israeli Jewish working class? Back in the 60s, the anti-Zionist semi-Trotskyist Matzpen made overtures to the Democratic Front for the Liberation of Palestine but failed to achieve its goals because the hands of the DFLP were bloody from attacking Israeli civilians.

Finally where in the Arab world have the national and religious rights of its non-Arab minorities been respected? No wonder that Israeli Mizrahi Jews, whose families were driven out of Arab lands as suspected Zionists, are hard to reach.

You ask, “where have the Palestinians made a cogent appeal to the Israeli Jewish working class?” In case you missed it, that’s kind of a central point of my article! We should make that appeal now!

You also ask, “Finally where in the Arab world have the national and religious rights of its non-Arab minorities been respected?” As Draper suggested, we should oppose Arab chauvinism along with Jewish chauvinism. I think Matzpen was right in 1969 when it supported self-determination (distinct from having a state) for Middle Eastern minorities including Kurds, Israeli Jews, and South Sudanese. See “The Middle East at the Crossroads.”

Great article, Dan. Bravo.

“We should make that appeal?” Who are you speaking for? The question is—what Palestinian organization is prepared to make this appeal? And will it include a recognition of national rights for Israeli Jews?

As I pointed out, Palestinians and Arab leaders have resisted this for decades–including bi-nationalism. In fact before 1967 or so, the PLO took the position that Jews who entered Palestine after the Balfour Declaration should all leave! At least until Oslo, the PLO took the position that Jews could at most live as a minority in a Palestinian Arab state. There are Palestinians today that still see Israel’s Jews are nothing more than Crusaders, foreigner invaders etc. Hamas circulates the Protocols of the Elders of Zion. Abbas minimized the Holocaust in his PhD dissertation and still denies that Jews have any roots in ancient Israel.

But We have digressed from my original argument. Israel is NOT hell for its Jews. For all of Israel’s flaws, Jews there are infinitely better off than they were in Europe (pre-during and post WW II), in the Soviet Union, in post-Soviet Russia and its successor states, in Arab and Muslim lands etc. There are seven million Jews living there. More than in the US in a country the size of New Jersey.

Do you really think Israeli Jewish workers will be won over by telling them that their homeland is “hell?”

I hope the BDS movement will take this approach of reaching out to Israeli Jewish workers! They already have to some degree, although you wouldn’t really know it from this book. I find it promising that unlike some of the other groups and individuals you’ve rightly criticized, BDS advocates “full equality” between Palestinians and Israeli Jews (2005 BDS call) and officially accepts Israeli Jews as members of the movement. For example, on 4 October 2016, the BDS website re-posted a statement from the Israeli group Boycott From Within. Interestingly, perhaps the Haymarket anthology’s only supportive mention of present-day Israeli Jewish activists comes from none other than BDS co-founder Omar Barghouti, on page 146.

To win more support from Israeli and world Jewry, supporters of a shared democratic country might also declare that the country would always welcome Jewish refugees alongside Palestinian refugees. Promisingly, Barghouti seems supportive of this position, as the NYT reports: “A democratic state could still provide asylum for Jewish refugees, showing ‘some sensitivity to the Jewish experience,’ he said, ‘but it cannot be a racist law that says only Jews benefit'” (“Is B.D.S. Anti-Semitic?,” NYT, 27 July 2019). Likewise, writings by Edward Said and Ali Abunimah support keeping a version of the Law of Return alongside a right of return for Palestinians (“The One-State Solution,” NYT, 10 January 1999; Ali Abunimah, One Country, 2007).

Okay, I will return to the original argument. I obviously use the word “hell” figuratively and would be open to your suggestion for a replacement. The point is, though, that Israeli Jews crave an escape from perpetual conflict with neighbors, from enduring internal inequality, and from the the government’s far-right turns. As Hannah Arendt warned in 1948, the success of political Zionism would mean that “Jews would live surrounded by an entirely hostile Arab population, secluded inside ever-threatened borders.” Surely, she was largely right, no? In a previous New Politics article, you have described life in southern Israel as often “unlivable” due to conflict between Israel and militants in Gaza. I think Israeli Jews would very much welcome a situation of peace and normality. I’m saying the BDS movement and one-democratic-state supporters should appeal to that sentiment and should try to convince Israeli Jews that they’ll make the country permanently “livable.”

Is there any Palestinian support for a bi-national state? Unless Israeli Jews are afforded recognition of their rights as a nation, there is no hope for peace. In fact, only after a long period of peaceful coexistence between two states would a bi-national state be conceivable. Israeli Jews will not give up their national identity and their right to self-determination.

Considering the arc of Jewish history, why would they? Life under Gentile control has too often proven disastrous. That is why they are generally happy living in a Jewish state. Most of the left and has been tone deaf to this reality.

How’s this? A 2007 poll by Near East Consulting found that 70% of Palestinians would support “a one-state solution in historic Palestine where Muslims, Christians and Jews have equal rights and responsibilities.”

http://www.neareastconsulting.com/surveys/ppp/p22/out_freq_q27.php/

https://electronicintifada.net/content/survey-70-percent-palestinians-support-one-state-solution/6773

As you know better than most, since you’ve written “Jewish Alternatives to Zionism,” there are a variety of ways that the Zionist state could be radically transformed/dismantled without Israeli Jews needing to give up their “national identity and their right to self-determination.”

I never said it would be easy, but I think if it’s possible at all then it’ll need the support of a significant number of Israeli Jews. That’s one of the reasons why I wrote this article.

And although I’m personally not convinced that a two-state solution is either desirable or realistic, I would still support BDS if I did. I think BDS is by far the best game in town in terms of peacefully pressuring Israel to end the occupation of the West Bank and Gaza Strip.

Here is the rub. Don’t you see how “Muslims, Christians and Jews” misses the point? This formulation limits “Jews” to a religious group only on par with “Muslims” and “Christians,” rather than a national group on par with Arabs. This “one state solution” favored by Palestinians would deny Jews their national rights.

So after all this remains the Palestinian position. Years ago, the PLO advocated a “democratic secular state” which sounded good, but was the same deception, because it posits that Palestinians Arabs are a nation, but Israeli Jews are not. This is not bi-nationalism by any stretch of the imagination.

Israeli Jews will never support this–and for good reason.

https://www.counterpunch.org/2019/01/03/what-kind-of-single-democratic-state-in-israel-palestine-do-we-want/

This article, I believe, will appeal to NP readers and, in fact, directly criticizes my point of view.

It supports the concept of one democratic state rather than a bi-national state.

In the interest of stimulating discussion, I provide the link.

Hi Bennett, thanks for sharing Alcott’s article. I am curious what you think of it. What specifically are the collective rights that you’re concerned Jews would lack under the secular democracy Alcott has proposed?

As I understood you above, you were concerned that Palestinian support for a “secular democratic state” and for “Muslims, Christians and Jews hav[ing] equal rights” really just meant supporting an Arab ethnostate. But doesn’t Alcott show that this is not necessarily the case? The One-Democratic-State movement’s solution would forbid “discrimination against…ethnic and religious groups” and “privileging…an ethno-religious group.”

In the same spirit of stimulating discussion, I would recommend checking out Palestinian writer Jonathan Kuttab’s bi-nationalist plan. I would be curious if you find it preferable to Alcott’s.

https://mondoweiss.net/2021/01/jonathan-kuttabs-one-state-vision/

“Kuttab provides his list of what those requirements might be for Jewish Israelis and for Palestinians. For the former, he suggests:

* A homeland with a Law of Return.

* Lasting security.

* A Jewish rhythm to public life.

* Official Hebrew language.

* Right to live anywhere in Israel/Palestine.

* Democracy, including individual and collective freedoms of speech, religion, peaceful assembly, free press, independent judiciary, representative government and rule of law.

For Palestinians:

* Democracy with political and legal equality — ironclad and constitutionally protected — similarly guaranteed to Jews if the demographic balance were to change in future years.

* Right of Return for Refugees, even if most are unlikely to ever move back.

* Right to freely move and live in all parts of Israel/Palestine, including Jerusalem. That would encompass the end of the siege of Gaza, the removal of the Wall and all the accoutrements of military occupation and government that comes with it.

* Official Arabic language and state recognition and respect for Palestinian Arab cultural identity.”

Kuttab’s vision is my own. Thanks for exposing me to it. I never heard of him before.

Alcott is not advocating a Palestinian ethnic state, but still appears to relegate Jews to the status of a religious group.

Back to Kuttab—I am not totally on board. Israeli Jews will never agree to a right to return of Palestinian refugees and their descendants on a massive scale. The face of Israel has changed dramatically since 1947-49. They have no place to return to. A solution to the refugee problem should be based on a combination of a limited return, of compensation and of resettlement in surrounding Arab nations that have shunned them for so many years.

Muskarin writes, “The face of Israel has changed dramatically since 1947-49. They have no place to return to.” I don’t agree. Palestinian geographer Salman abu-Sitta reported in 2008 that “well over 90% of the refugees could return to empty sites” and “77% of Jews live in 15% of Israel’s territory.”

Unless these stats have drastically changed in the past decade, there is plenty of room for refugees to return. In those cases where refugees’ former homes are currently occupied by Israelis, abu-Sitta suggests an example of a very reasonable compromise: Refugees “could retain the property rights and grant a 49-year lease to existing occupants, most of which are institutions. Meanwhile, they could rent or build housing for themselves in the vicinity.”

Dan’s article raises many excellent points. However I think the comparison of appealing to Israeli Jewish (colonial-settler) workers just as we try to appeal to U.S. (colonial-settler) workers is rather stretched. U.S. unions have been fully integrated for many decades, even construction. The Israeli Histadrut campaigned only for Jewish labor for its first 40 years of existence and picketed when employers would hire Palestinians. It let “Arabs” in 1959, but it was OK with Israeli Arabs being excluded from so-called “security industries”. It will represent Jewish workers in the West Bank, but not Palestinians. When Palestinians work inside of ’48 Israel they get a chunk of wages deducted for which the Histadrut gets a slice and for which these workers get virtually nothing. I don’t at all oppose approaching Israeli workers, but suggest it will be a difficult road to hoe.

I think a better comparison than with U.S. workers is with the anti-apartheid movement and South African white workers. I did some solidarity anti-apartheid work in the ’80’s. I don’t recall any solidarity coming from white South African organized (or unorganized) labor. There were some amazing white activists in the RSA, but I don’t recall them being active “as workers”. It would be great if we could get input from South Africans about this and not have to start from scratch.

Thanks for the critical comments, Stan. My starting point is support for decolonization, and I think it’s unlikely that goal will supported by establishment unions in either Israel or the United States. Here in the United States, the pro-capitalist unions might formally let in Native Americans (the closest analogue to Palestinians), but that doesn’t mean they are soon going to respect Indigenous demands for returning the land and ending destructive infrastructure. As you know, the AFL-CIO supported the Keystone XL and Dakota Access pipelines and opposes the Green New Deal on the grounds that it will hurt the fossil fuel industry.

In both the U.S. and Israeli cases, I think the joint struggle will not come from (mainstream) union leadership but will come from below, from the broadly-defined working class whether or not they are organizing “as workers.”

My article gave some reasons why Israeli Jewish workers might turn against Zionism and align with Palestinians. I think that reversing climate and ecological breakdown is one reason U.S. workers might turn against settler colonialism and align with Native Americans who are trying to protect their land from ecocide. I don’t see how decolonization can be achieved without mass Israeli Jewish and white American support, since those groups constitute the majority in their countries. By contrast, South African whites comprised only 15% of the population, so it wasn’t quite as critical to win them over.