By now you will have read about the strikes of 2021. For one thing, there are more of them, some in industries where we haven’t seen many strikes for a while like retail, entertainment, or major manufacturing firms; others in areas that became more strike prone in recent years like health care and education: almost all where workers were affected by the COVID-19 pandemic. For the more cautious commentators this has been an “uptick” in walkouts, while former Labor Secretary Robert Reich has imaginatively suggested it was “in its own disorganized way” a general strike.”[1] Most accounts of this visible surge in strike activity place it in the context of the recent economic conjuncture.

By now you will have read about the strikes of 2021. For one thing, there are more of them, some in industries where we haven’t seen many strikes for a while like retail, entertainment, or major manufacturing firms; others in areas that became more strike prone in recent years like health care and education: almost all where workers were affected by the COVID-19 pandemic. For the more cautious commentators this has been an “uptick” in walkouts, while former Labor Secretary Robert Reich has imaginatively suggested it was “in its own disorganized way” a general strike.”[1] Most accounts of this visible surge in strike activity place it in the context of the recent economic conjuncture.

The immediate conditions encouraging strike action are mostly sought in the unique labor “shortages” in which (aside even from those down with the virus) workers have voluntarily left their jobs in search of better pay and conditions in record numbers. The Bureau of Labor Statistics calls these “quits” and records an unprecedented 4.3 million of them by August of this year. Those in trade, transportation, and utilities and leisure and hospitality alone accounted for almost half of these.[2] On the other hand, private sector layoffs are down from a year earlier and job openings up by over two-thirds to 9.6 million, while hirings are nearly flat.[3] Bosses need more workers and workers have gotten more choosey and assertive.

While some call it “The Great Resignation” due to all the “quits”, others have labelled it the “Great Discontent” for the underlying anger that leads to action whether a quit or a strike.[4] For one thing, the quit rate had been growing more or less steadily since the first signs of recovery after the 2008-2010 Great Recession. For another, a Gallup poll in March 2021 found that 48 percent of “America’s working population is actively job searching or watching for opportunities,” far more than the 2.9 percent actually quitting.[5] So, job dissatisfaction has reigned throughout the work force for some time before reaching its all-time high in August 2021. For this reason, I believe it is more helpful to see the “quit” rate as a measure of job dissatisfaction, on the one hand, and the confidence to act, on the other, rather than a direct cause of strikes

At the same time, millions of under-paid workers have discovered, if they didn’t already know, that they were “essential” to society’s functioning—even as their bosses continued to abuse, overwork, and underpay them. This, too, contributed to the willingness to strike. On top of that, after falling during the spread of the pandemic in the spring of 2020, domestic nonfinancial corporate profits soared by 70 percent to a record $.1.8 trillion by the second quarter of 2021 so the employers have a harder time claiming poverty should their workers take notice and take a stand.[6] Matters were certainly helped by the 450 union contracts, many covering over 1,000 workers that expired in 2021.[7] Altogether it’s been a good time to strike.

But there is more to this apparent trend in militancy than a favorable labor market. To look a little deeper into this we need to examine what came before. The strikes of 2021 did not come out of nowhere. Table I shows the total number of strikes, those considered “major” by the BLS with 1,000 or more strikers, and the total number of strikers for the past six years.

Digression of Strike Statistics

Before analyzing these and related numbers, however, a discussion of strike figures is necessary. Since the Reagan administration discontinued the BLS count of all work stoppages after 1981, there is no official count of all strikes and lockouts. The BLS counts only strikes of 1,000 or more workers. Until 2021, the Federal Mediation and Conciliation Service (FMCS) counted all work stoppages directly involved in mostly private sector collective bargaining. So strikes such as those of the West Virginia teachers and others in in 2018 and 2019 were not included since they were in effect strikes against the West Virginia legislature. Neither were most public sector strikes unless the union or employer appealed to the FMCS for mediation. So, even combining the BLS major strikes with the FMCS figures would not necessarily produce a totally accurate count. The Biden Administration has let the FMCS count lapse and it is no longer available on the FMCS website, making matters worse. Strikes by railroad and airline workers are counted by the National Mediation Board under the terms of the Railway Labor Act. There have been none of these, however, in the years we are looking at.

This year, on the other hand, the Cornell University Industrial and Labor Relations program has begun tracking of all strikes via Google and social media. Even more recently, Jonah Furman of Labor Notes began recording strikes and organizing efforts in his “Who Gets the Dog” weekly online report. I have used all of these sources to produce the most accurate count of strikes possible with the existing materials, but it is likely some have been missed. It is these figures used in Table I and throughout this article which will differ at times from and are more accurate than the available BLS or FMCS counts alone. They are cited under Tables I and II and won’t be cited each time they are used subsequently.

_________________________________________________________________________

Table I

Strikes 2016-2021

Year Total #Strikes* #Major Strikes #Strikers

2021** 194 16 73,320

2020 66 9 41,747

2019 89 24 432,484

2018 76 26 533,328

2017 98 10 45,941

2016 99*** 20 115,050

*ILR Labor Action Tracker counts individual locations that are clearly part of a larger strike by the same union, as for example at John Deere, as separate work stoppages. I count them together as a single strike.

**Jan-Oct.

*** FMCS counts 2016 SEIU Florida nursing home strikes 15 separate strikes, as they were simultaneous I count them as one.

Sources: ; Cornell ILR “Labor Action Tracker” , https://striketracker.ilr.cornell.edu/; BLS, “Major Work Stoppage” Monthly, https://www.bls.gov/web/wkstp/monthly-listing.htm ; Federal Mediation and Conciliation Service, “Ongoing and Ending Work Stoppages, “ Monthly, 2017-2019; Federal Mediation and Conciliation Service Annual Report 2009-2017; Jonah Furman, “Who Gets the Bird”, Weekly, September and October 2021, whogetsthebird@substack.com; National Mediation Board (airlines and railroads), “Strikes”, https://nmb.gov/NMB_Application/index.php/page/7/?s=strikes

Three things stand out from these figures. First, the total number of strikes in the first ten months of 2021 is far greater than those of the previous five years. On the other hand, the number of strikers is not larger than for all previous years. In general, the number of strikes has been declining since 1980 and fell even further after the great Recession of 2008, hitting a low of 76 in 2018. 2021 is, thus, the first year of a significant uptick in the total number of strikes. But as Table I shows, the number of strikers in 2021 does not even come close to match those of 2018 and 2019, which saw massive teacher strikes sweep the country. In fact, prior to 2021, the bulk of strikes have come from public school education and mostly private health care workers. These are workers who are less affected by economic ups and downs than most, although their quit rates also rose indicating significant job dissatisfaction. Of course, they are workers facing conditions common to much of the working class and their strikes count in the bigger class struggle as much as those of other more “industrial” workers.

Second, however, is a dramatic slump in both the number of strikes and strikers in 2020 as a result of the initial impact of the pandemic in general and the deep if brief recession it produced in the spring of that year. It should be noted, however, that many of the strikes that did occur in 2020 were those by non-union workers at outfits like Amazon, McDonald’s, and Instacart protesting unsafe conditions in the face of the rising pandemic.[8] The increase in strikes resumed, however, in 2021. Third, what makes 2021 in particular unique is not only the increase in numbers, but the increase in non-teacher, non-health care, mostly private sector strikes. There were 124 strikes by these workers across industries in 2021, far more than in any of the earlier post-Great Recession years. Table II show all those strikes by 500 or more workers This doesn’t include the 60,00 IATSE entertainment workers who reached a tentative agreement in October, but who have expressed dissatisfaction with the settlement. Or others, like the 37,000 Kaiser Permanente health care workers who may strike later in the year. Or, indeed, the many others facing contract expirations in the coming year. So, there is a broader “uptick” in strike activity following the dislocating impact of the pandemic.

Strikes of 500 or more workers in 2021 through October

Employer Union # Strikers

Hunts Point IBT 1,400

Columbia U. GWC-UAW 3,000

Allegheny Technologies USW 1,300

Warrior Met Coal UMWA 1,100

Volvo Trucks UAW 2,900

John Deere UAW 10,000

NYU GSOC 2,200

Chicago local gov’t SEIU 73 2,000

Belleville Schools NEA 1,400

Nabisco BCTW&GMU 21,000

Kellogg’s BCTW&GMU 1,400

WA General Contractors UBCJ 22,000

Mercy Hosp. Buffalo CWA 2,200

Frontier Communications CWA 2,000

Puerto Rico Police Bureau 1,500

Keck Medical Center USC CNA 1,400

Cook County Health Care NNU 1,200

Oakland University AAUP 880

St. Vincent’s Hospital MA Nurses 800

New Car Dealers, IL. IAM 800

Kaiser Permanente IUOE 700

San. Francisco Maintenance SEIU 700

Frito-Lay BCT&GMU 600

National Aerospace Metal Trades Council 600

Peoria Schools, AZ Teachers’ Union 600

- Baton Rouge Schools NEA 600

ArcelorMittal USW 500

Totals 24 (13% of Total) 60,280 (82% of 2021 Total)

Sources: Cornell ILR Labor Action Tracker, , https://striketracker.ilr.cornell.edu/; BLS,” Major Strikes” Monthly Listing, Jan-Oct, https://www.bls.gov/web/wkstp/monthly-listing.htm; Jonah Furman, “Who Gets the Bird,” Sept-Oct, 2021.

A slightly broader way to see this trend is as a long term “recovery” from the deep dislocation of the Great Recession of 2008-2010. The number of strikes recorded by the FMCS and the BLS had been falling for decades. In the late 1990s those recorded by the FMCS ran at an average close to 400 a year, falling to about 300 annually from 2000 to 2005 and slumping to a low of 103 in 2009. Major strikes measured by the BLS fell from 39 in 2000 to an all-time low of 5 in 2009. The number of strikes in this BLS account fell from 394,000 in 2000 to an incredible low of 12,500 in 2009. So, while none of the pre-recession figures represent historically high levels of strikes comparable to the 1930s, 1940s, or 1970s, the Great Recession did represent a fairly sharp downturn in strike activity. Seen in this way, the figures from 2018 to 2021 taken together and averaged can be interpreted as a return to pre-recession levels of strikes and strikers.

Seen in another way, however, workers learn from the victories of other workers and from the perception that their own conditions are shared by others across society. The education workers of 2018 and 2019 were, indeed, teaching others that when the conditions are right, the time to strike and win has come. Along with the many health care strikers taking on corporate giants they were also showing workers across industries that the experience of years of stagnant income and the stresses of lean, just-in-time work were the maladies of an entire class. If they could fight back, so could you.

The Accumulation of Grievances v. the Accumulation of Capital

There is, therefore, reason to believe that strike action and militancy in general will continue if we understand the “uptick” of 2018-2021 as the result not only of pandemic and conjunctural conditions, but of the accumulation of grievances over a long period. A period that is the result of capital’s desperate efforts to increase profits and off-set falling profit rates that returned soon after the recovery from the collapse of 2008-2010.[9] As British labor historian Eric Hobsbawm put it in his study of worker upsurges, “explosive situations” are the result of “accumulations of inflammable material which only ignite periodically, as it were, under compression.” [10] The inflammable materials are the declining conditions of pay, work, and life and the accumulated grievances from these over many years. While such worker “explosions” are impossible to predict with any accuracy, they are always preceded by rising protests, strikes, and sometimes new or expanded organization often accompanied by other active social movements. Well-known examples include the strike waves before and after World War One, that during and after World War Two, and the strike wave that lasted from the mid-1960s through the 1970s during the Vietnam War era.

Each of these strike waves was not only disrupted and then driven by the social and economic impact of a war but accompanied by and interrelated with other major social movements in addition to that of unionized and unionizing workers. In the years around World War One these were the movement of women’s suffrage and the rise of civil rights activity mainly through the NAACP and of Black Nationalism. In the years following World War Two it was not only the massive strike wave of 1943-to 1946, but the less visible yet important stirrings of civil rights activity often led by black veterans. The Vietnam war era saw the anti-war movement, the rebirth of feminism and the mass women’s movement along with Black Power and the LGBTQ rights movement. Today’s “uptick” occurs, of course, in the wake of a renewed women’s movement, the immigrant workers’ movement, the movement to halt climate change, and the rise of Black Lives Matter and its various off-springs. It is already a period of considerable social activism. The strike “uptick” is possibly the precursor to a more substantial “explosion.”

While many of the declining conditions of working-class life and the grievances they have spawned are well-known, it is worth looking into them and how they might interact to produce a continued upswing in working class militancy and activism. Perhaps the most obvious and grating issue is that in real terms despite some recent wage increases due to the labor “shortage,” in September of this year the average private sector production and nonsupervisory worker was making the same $9.73 an hour she would have made in the spring of 1989, while labor productivity rose by 88 percent over those years, including even significantly during the pandemic. [11] You might not know the official figures, but you surely knew the situation by now.

As the pandemic hit in early 2020, some two-thirds of the lowest-paid workers and only about half of those at the bottom 25 percent of the wage scale, or about 13 million production and nonsupervisory workers had no paid sick leave at all, while over 31 million persons under 65 had no health insurance.[12] Not surprisingly, the impact of the pandemic was not socially neutral. A study by the Journal of the American Medial Association Network published in May 2021 revealed that the incidence of COVID-19 infections and deaths was greater in those US counties with relatively high-income inequality.[13]

Alongside this gruesome economic reality, years of lean just-in-time work intensification, standardization, and quantification have taken their toll in stress. Looking at the US and Canada during the pandemic in 2020, a Gallup poll found that 57 percent of workers experienced stress, 48 percent worried, and 22 percent felt anger all of them “a lot of the day.”[14] Stress, worry, and anger, moreover, were on the rise well before the pandemic hit. The percentage of Americans who said they had experienced these “a lot of the day,” rose over the post-Great Recession period from 44 percent in 2008 to 55 percent for stress in 2018, 34 percent to 45 percent for worry, and 16 percent to 22 percent for anger over those years.[15] An earlier poll taken in 2006 showed that 72 percent of the stress experienced in the US came from work-related causes.[16]

Stress, however, was not the only source of emotional distress and discontent. Years of increasingly visible income and wealth inequality exploded during the pandemic revealing a picture of obscene net worth of the nation’s growing cohort of billionaires. According to a study by the Institute for Policy Studies, the number of US billionaires grew from 614 in March 2020 to 745 in October 2021 as the pandemic surged, while their accumulated wealth soared from $2,947.5 billion to $5,019.4 billion over that period. The well-publicized antics of many of these titans of exploitation have made it all but impossible for the working-class public not to notice how these high-profile individuals have profited off the overwork, underpay, stress, infection, and even death of the majority. In fact, even before the pandemic took hold a majority of 61 percent said there was “too much economic inequality in the U.S.” On average only 42 percent of those questioned thought tackling this inequality was a “top priority”, but among these with lower-incomes 52 percent thought it a top priority.[17] For many at least, this astronomical growth of inequality was one more reason to strike and one more building block in class consciousness.

At the same time, even before the pandemic was sighted, 70 percent of Americans felt that “big corporations and the wealthy have too much power and influence in today’s economy, according to a poll taken by the Pew Research Center in late September 2019. Not surprisingly, perhaps, they also thought politicians had too much power. The feeling that powerful “interests” have too much economic power and political influence is, of course, also grist for right wing Trump-style populist mills as well as a potential source of class consciousness. In any case, watching the Democrats in Congress fight each other as much as the Republicans and corporate lobbyists as they whittle down even the initially inadequate programs that might help working class people is likely to kill whatever hope some might have had that help would come from that quarter. On the other hand, only 31 percent said labor unions had too much power and most of those identified as or leaned Republican.[18] In fact, approval rating of unions have been climbing in the post-Great Recession era from a low of 48 percent in 2009 to 68 percent in August 2021.[19] This, too, indicates both increased discontent and class awareness—and the immediate means by which to fight effectively.

Given the accumulation of grievances and the poor contracts union workers have seen for decades now, it is not surprising that the pressure for strikes and better contracts has come largely from the ranks. Rob Eafen, President of the BCT&GMU local at the Kellogg’s plant in Memphis told Time “The movement to strike was a groundswell, from the people.”[20] The groundswell was visible across many of the unions whose contracts expired in 2021 as members voted by huge majorities to strike. In October, members of the United Auto Workers (UAW) at John Deere rejected a contract offer by 90 percent and voted to strike by 98 percent, as did UAW members at Volvo truck plants who rejected inadequate offers twice by 90 percent and struck. Communications Workers (CWA) at Frontier Communications in California voted by 93 percent and then struck for a day on October 5. [21] Members of IATSE, the union of workers behind the production of movie and TV shows, voted by 98 percent to strike in early October. A tentative agreement was subsequently reached, but many IATSE members expressed dissatisfaction with the offer.[22] 21,000 nurses and other health care workers at Kaiser Permanente in California voted by 96 percent for strike action if necessary, with thousands more Kaiser worker in 20 more unions set to vote as well. [23] There is little reason to believe that this sort of pressure from below will disappear.

Crises such as wars, depressions, and pandemics expose all kinds of fissures in the economic system. The COVID 19 pandemic has simply magnified and broadcast the accumulated inequities of society and the grievances they spawn, but also the vulnerability of capital. The recent collapse of global just-in-time supply chains, for example, is the proximate cause of a crisis long in the making. Ports are clogged up in part because container ship capacity has out-paced container port capacity 63 percent to 42 percent from 2010 to 2020, followed by a sharp increase in container shipping demand in 2021. This was due to the switch of consumers from services to goods during the pandemic.[24] There were also pre-existing shortages of railroad cars, engines, and workers, as well as local and long-haul truck drivers and warehouse workers; that is all along the supply chains.[25] The impact of these sources of congestion and bottlenecks in the world’s supply chains were intensified by the combination of the pressures and vulnerabilities of just-in-time delivery. There is no mystery about either of these problems. Speed increases the impact of any supply chain disruption,[26] while years of low wages and benefits, combined with the results of work intensification mentioned above have kept workers away from the stressful and dangerous jobs involved in moving the worlds goods, as they have from other areas of work such as health care as well.

At the same time, this is a reminder of the power of labor to disrupt the accumulation of capital. A study of the impact of “disruptive events” on the supply chains of 397 US firms between 2005 and 2014 showed that for three-months after the disruption an average impact on sales of only -4.85 percent produced an operating income decrease of -26.5 percent and decline in return on assets of -16.1 percent. [27] This impact was before the pandemic brought an increase in the rise of goods consumption compared to services along with even tighter inventories and, hence, increased dependence on supply chains and logistics that are not likely to end for some time.[28] Clearly, labor-produced disruptions such as strikes or work-to-rule actions can have a significant impact on the accumulation of capital of any given employer. An upsurge can force retreat on the entire capitalist class. And that could be a starting point for a new working-class movement in the US.

[1]Alex Press, “US Workers Are in a Militant Mood”, Jacobin, October 15, 2021, https://www.jacobinmag.com/2021/10/american-workers-labor-militancy-covid-19-strike-unions ; Robert Reich, “Is America Experiencing an Unofficial General Strike?”, The Guardian, October 13, 2021, https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2021/oct/13/american-workers-general-strike-robert-reich

[2] Bureau of Labor Statistics, “Quits rate of 2.9 percent in August 2021 an all-time high”, TED: The Economic Daily, October 18, 2021.

[3] Bureau of Labor Statistics, “Job Openings and Labor Turnover-August 2021,” News Release, USDL-21-1830, October 12, 20210, Tables 1-6.

[4] Vipula Gandhi and Jennifer Robison, “The ‘Great Resignation’ Is Really the ‘Great Discontent,’” Gallup, July 22, 2021, https://www.gallup.com/workplace/351545/great-resignation-really-great-discontent.aspx

[5] Gandhi and Robison; Bureau of Labor Statistics, “Quit rate”.

[6] Bureau of Economic Analysis, “Table 6.16D. Corporate Profits by industry,” September 30, 2021, https://apps.bea.gov/iTable/iTable.cfm?reqid=19&step=3&isuri=1&1921=survey&1903=239#reqid=19&step=3&isuri=1&1921=survey&

[7] Rand Wilson and Peter Olney, “Swarming Solidarity: How Contract Negotiations in 2021 Could Be Flashpoints in the U.S. Class Struggle,” Labor Notes, January 14, 2021, https://www.labornotes.org/2021/01/swarming-solidarity-how-contract-negotiations-2021-could-be-flashpoints-us-class-struggle.

[8] Bridget Read, “Every Food and Delivery Strike Happening Ovoer Coronavirus,” The Cut, May 27, 2020, https://www.thecut.com/2020/05/whole-foods-amazon-mcdonalds-among-coronavirus-strikes.html; Celine McNicholas and Margaret Poydock, “Workers are striking during the coronavirus,” Working Economics Bog, Economic Policy institute, June 22, 2020, https://www.epi.org/blog/thousands-of-workers-have-gone-on-strike-during-the-coronavirus-labor-law-must-be-reformed-to-strengthen-this-fundamental-right/.

[9] For profit rates see Michael Roberts Blog, “Profits call the tune,” June 17, 2021, https://thenextrecession.wordpress.com/2021/06/17/profits-call-the-tune-2/

[10] Eric Hobsbawm, “Economic Fluctuations and Some Social Movements since 1800,” in Eric Hobsbawm, Labouring Men: Studies in the History of Labour (London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1964), 139.

[11] Bureau of Labor Statistics, “Real Earnings – September 20201, Real Earnings New Release, USDL-21-1832, October 13, 2021, Table A-2; Bureau of Labor Statistics, “Average hourly earnings of production and nonsupervisory employees, Total private, seasonally adjusted,” 1972 to 2021, Databases, Tables & Calculators by Subject, extracted on October 25, 2021; Bureau of Labor Statistics, Economic New Release, Table 1Business Sector Labor Productivity, September 2, 2021, https://www.bls.gov/news.release/prod2.t01.htm; Bureau of Labor Statistics, “Nonfarm Business Annual Series” All Employed Persons, Index 2012 = 100, 1947-2020, xlxs, https://www.bls.gov/lpc/#tables.

[12] Elsie Gould, “Two-thirds of low-wage workers still lack access to paid sick days during an ongoing pandemic,” Economic Policy Institute, September 24, 20201, https://www.epi.org/blog/two-thirds-of-low-wage-workers-still-lack-access-to-paid-sick-days-during-an-ongoing-pandemic/; National Center for Health Statistics, “Health Insurance Coverage,” FastStats, October 19,2021, https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/fastats/health-insurance.htm.

[13] Annabel X. Tan, MPH; Jessica A. Hinman, MS; Hoda S. Abdel Magid, PhD; Porene M. Nelson, PhD, MS; and Michelle C. Odden, PhD, “Association Between Income Inequality and County-Level COVID-19 Cases and Deaths in the US,” JAMA Network OPEN. May 3, 2021, https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamanetworkopen/fullarticle/2779417.

[14] Gallup, State of the Global Workplace: 2021 Report, (Washington DC: Gallup, 2021), 28-30.

[15] Julie Ray, Americans’ Stress, Worry and Anger Intensified in 2018,” Gallup, April 25, 2019, https://news.gallup.com/poll/249098/americans-stress-worry-anger-intensified-2018.aspx.

[16] The American Institute of Stress, “Main Causes of Stress, “ 2006 StressPulse Survey, 2020, https://www.stress.org/workplace-stress.

[17] Pew Research Center, January 2020, “Most Americans Say There Is Too Much Economic Inequality in the U.S., but Fewer Than Half Call it a Top Priority,”https://www.pewresearch.org/social-trends/2020/01/09/most-americans-say-there-is-too-much-economic-inequality-in-the-u-s-but-fewer-than-half-call-it-a-top-priority/

[18] Pew Research Center, “70% of Americans say U.S. economic system unfairly favors the powerful,” January 9, 2020, https://www.oewresearch.org/fact-tank/2020/01/09/70-of-americans-say-u-s-economic-system-unfairly-favors-the-powerful/

[19] Gallup, “Approval of Labor Unions at Highest Point Since 1965”, September 2, 2021, https://news.gallup.com/poll/354455/approval-labor-unions-highest-point-1965.aspex

[20] Abby Vesoulis and Julia Zorthian, “Workers Are Furious. Their Unions Are Scrambling to Catch Up, “ Time, October 25, 2021, https://time.com/6110014/worker-anger-unions.

[21] Jonah Furman, “John Deere Workers Are Ready to Strike on Wednesday,” Jacobin, October 12, 2021, https://www,jacobinmag.ocom/2021/10/john-deere-workers-uaw-contract-vote-strike; Jonah Furman, “Deere Strikers Mean Business,” Labor Notes 512 November 20201, 1, 3, 15..

[22] Jonah Furman and Gabriel Winany, “The Strike Wave Shows the Tight Labor Market Is Ready to Pop,” Labor Notes, October 18, 2021, https://www.labornotes.org/2021/10/strike-wave-shows-tight-labor-market-ready-pop; .

[23] Suhauna Hussain, “Kaiser Permanente workers vote to authorize strike, citing staffing and safety concerns,” Los Angeles Times, October 11, 2021, https://www.msn.com/en-us/news/us/kaiser-permanente-workers-vote-to-authorize-strike-citing-staffing-and-safety-concerns/ar-AAPojIZ?ocid=BingNewsSearch

[24] Statisa, “Capacity of container ships in seaborne trade from 1980 to 2020 (in million dead weight tons)” and “Container capacity at ports worldwide from 2002 to 2019 with a forecast for 2020 until 2024 (in million TEUs),” 2021, https://www.statista.com/search/?q=global+port+capacity&Search=&qKat=search; Peter Sand, “Container Shipping: Records Keep Falling As Industry Enjoys Best Markets Efver,” Bimco, June 21, 2021, https://www.bimco.org/news/Market_anaysis/20210602_container_shipping.aspx; Paul Krugman, “The Revolt of the American Worker,” New York Times, October 14, 2021, .

[25] Jared Faker and Rich Austin, Jr., “Dockworkers are available 24/7—others in supply chain should be, too,” The Seattle Times, October 25, 2021, https://www.seatlletimes.com/opinion/dockworkers-are-available-24-7-others-in-supply-chain-should-be-too/; Abba Bhattariai, “Warehouse jobs—recently thought of as jobs of the future—are suddenly jobs few workers want,” Washington Post, October 11, 2021, https://www.washingtonpost.com/business/2021/10/11/warehouse-jobs-holidays-seasonal-hiring/

[26] Kim Moody, “Labour and the Contradictory Logic of Logistics” Work Organisation, Labour & Globalisaton 13(1) (Spring 2019): 79-95.

[27] Milad Baghersad and Christopher W. Zobel, “Assessing the extended impacts of supply chain disruptions on firms: An empirical study,” International Journal of Production Economics 231, January, 2021: 8.

[28] Peter S, Goodman, “How the Supply Chain Broke, and Why It Won’t Be Fixed Anytime Soon,” New York Times, October 22, 2021, https://www.nytimes.com/2021/10/22/business/shortages-supply-chain.html; Krugman, 2021..

[Editor’s note: An archived version of the event can be seen here:

[Editor’s note: An archived version of the event can be seen here:

In October and November of 2019, clashes over the validity of presidential elections in Bolivia led to protests and the eventual ouster of the leftist Indigenous president Evo Morales, in what most observers characterized as a coup. In the year that followed, the interim regime, led by Jeanine Añez, oversaw a deeply repressive regime that confronted protests on two occasions with large-scale killing by the military. The year of de facto rule was further compounded by COVID and by corruption, with widespread theft and graft. When new elections were finally held in October of 2020, the ousted party returned to power with a new president, Luís Arce. Evo Morales came back from exile in Argentina, and the resurgent MAS party – the ‘Movement Toward Socialism’ – took back the state. Now a year later, President Luís Arce continues to grapple with an extremist right-wing opposition and the challenges of governing in a post-coup scenario amidst an ongoing pandemic. Against ongoing efforts by the right-wing to destabilize the new president, the country’s robust peasant and worker social movements, in large part rural and Indigenous, continue to turn out in the streets to offer their ongoing support – both for Arce and for the democratic mandate he won in the polls.

In October and November of 2019, clashes over the validity of presidential elections in Bolivia led to protests and the eventual ouster of the leftist Indigenous president Evo Morales, in what most observers characterized as a coup. In the year that followed, the interim regime, led by Jeanine Añez, oversaw a deeply repressive regime that confronted protests on two occasions with large-scale killing by the military. The year of de facto rule was further compounded by COVID and by corruption, with widespread theft and graft. When new elections were finally held in October of 2020, the ousted party returned to power with a new president, Luís Arce. Evo Morales came back from exile in Argentina, and the resurgent MAS party – the ‘Movement Toward Socialism’ – took back the state. Now a year later, President Luís Arce continues to grapple with an extremist right-wing opposition and the challenges of governing in a post-coup scenario amidst an ongoing pandemic. Against ongoing efforts by the right-wing to destabilize the new president, the country’s robust peasant and worker social movements, in large part rural and Indigenous, continue to turn out in the streets to offer their ongoing support – both for Arce and for the democratic mandate he won in the polls.

[Editor’s note: The original posting invited readers to join us for a roundtable Jan. 20, 2022, 7:30 pm (EST) as Lois Weiner and a panel of teacher union activists discuss the first chapter of her book, appearing here and in the Winter 2022 print issue.

[Editor’s note: The original posting invited readers to join us for a roundtable Jan. 20, 2022, 7:30 pm (EST) as Lois Weiner and a panel of teacher union activists discuss the first chapter of her book, appearing here and in the Winter 2022 print issue.

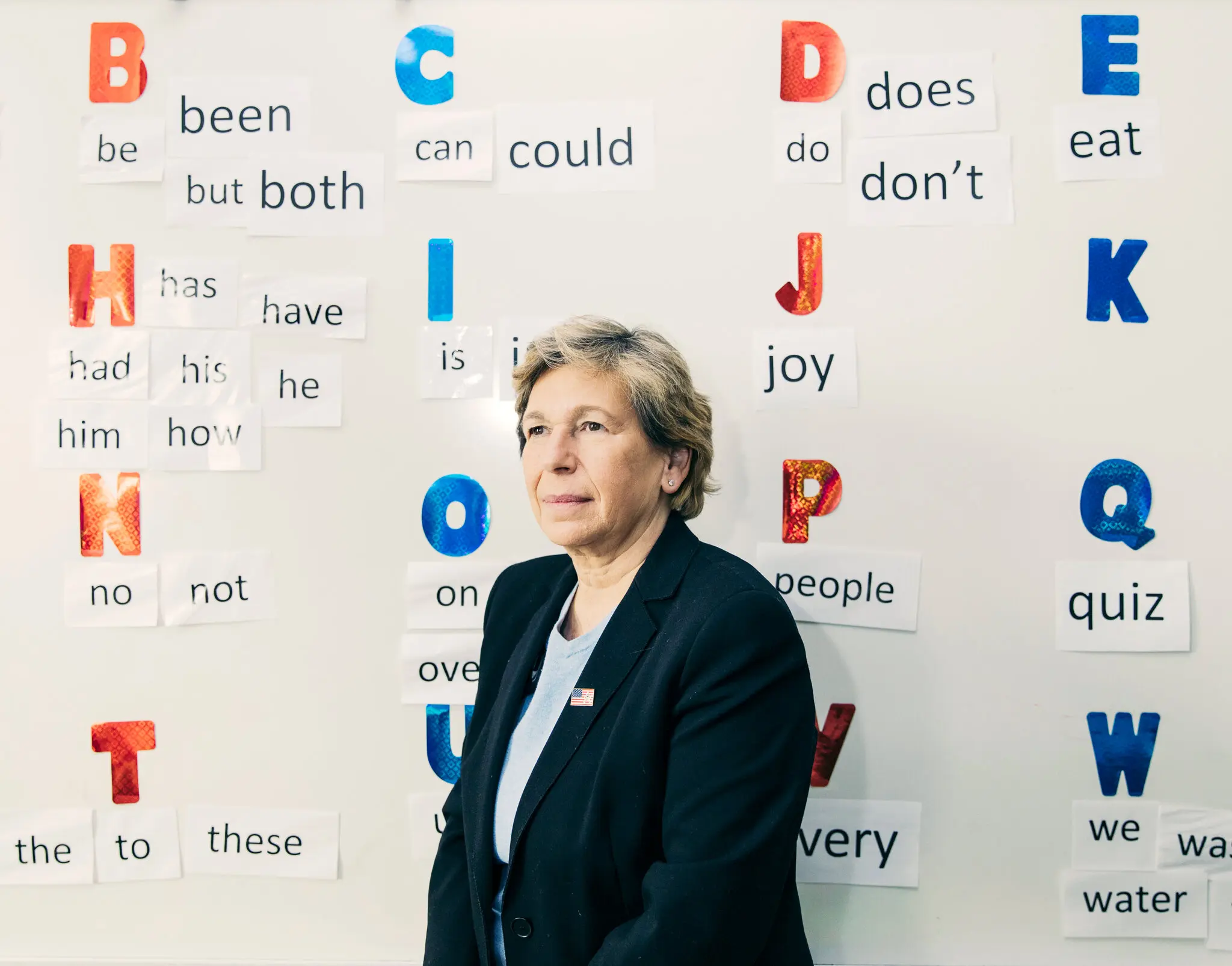

It’s revealing the only idea Randi Weingarten, President of the American Federation of Teachers (AFT), gets right in the

It’s revealing the only idea Randi Weingarten, President of the American Federation of Teachers (AFT), gets right in the

Frieda Afary conducted this interview with a representative of the Revolutionary Association of the Women of Afghanistan (RAWA) via the internet.

Frieda Afary conducted this interview with a representative of the Revolutionary Association of the Women of Afghanistan (RAWA) via the internet.

By now you will have read about the strikes of 2021. For one thing, there are more of them, some in industries where we haven’t seen many strikes for a while like retail, entertainment, or major manufacturing firms; others in areas that became more strike prone in recent years like health care and education: almost all where workers were affected by the COVID-19 pandemic. For the more cautious commentators this has been an “uptick” in walkouts, while former Labor Secretary Robert Reich has imaginatively suggested it was “in its own disorganized way” a general strike.”

By now you will have read about the strikes of 2021. For one thing, there are more of them, some in industries where we haven’t seen many strikes for a while like retail, entertainment, or major manufacturing firms; others in areas that became more strike prone in recent years like health care and education: almost all where workers were affected by the COVID-19 pandemic. For the more cautious commentators this has been an “uptick” in walkouts, while former Labor Secretary Robert Reich has imaginatively suggested it was “in its own disorganized way” a general strike.”

A rising fight that focuses on tenure

A rising fight that focuses on tenure

The Freedom in the World 2021

The Freedom in the World 2021