Baltimore is a category 5 hyper-segregated city or what Public Health scholar Lawrence Brown called “an apartheid city due to 105 years of racist policies and practices.” Brown wrote,

Baltimore’s hypersegregated neighborhoods experience radically different realities. Due to this dynamic, the White neighborhoods on the map that form the shape of an ‘L’ accumulate structured advantages, while Black neighborhoods, shaped in the form of a butterfly, accumulate structured disadvantages. Baltimore’s hypersegregation is the root cause of racial inequity, crime, health inequities/disparities, and civil unrest1” (2016a).

Following Brown’s observations, many scholars and journalists have gone so far as to describe the White L and Black Butterfly as two separate Baltimores: one of hyper-investment and capital accumulation and the other of hyper-disinvestment and decay. Perhaps this is why, while there has been a lot of scholarship written about East and West Baltimore (the “wings” of the black butterfly), the southern part of the city (majority Black and of color yet not a part of Brown’s “butterfly”) often gets left out of the historiography. Included in the forgotten south, is the neighborhood of Cherry Hill2 and included in Cherry Hill, is the Black Yield Institute (BYI). In what follows, we provide a brief history of the founding and evolution of Cherry Hill, before describing Black Yield Institute as the Black-led grassroots organization leading the fight against food apartheid, and the importance of the Green New Deal.

Cherry Hill History

Cherry Hill was a result of one of the “ugliest episodes of white rage in Baltimore’s history.3” (Noor 2019) This “toxic” and peripheral land was chosen by the city for the placement of a housing project at a moment when there was a housing shortage for industrial workers. Many Black people had migrated to Baltimore during the 1940s in search of decent industrial jobs. The Cherry Hill community was developed in an act of legislation known as the Servicemen Readjustment Act of 1944, also known as the GI BILL, which assisted returning vets with employment, education, and housing. Baltimore City officials were compelled by political mandate, overpopulation, and a public health crisis to make the land and housing available for Black families. The Housing Authority of Baltimore City (HABC) chose this site because of its isolation from the rest of the city given white opposition to integrated neighborhoods4 (Winbush et al 2015). The NAACP protested this location for the placement of public housing projects due to “unsuitable environmental conditions.” There were several industrial plants, the city’s Reedbird Incinerator, a landfill site, and many other environmental hazards already in the region. Despite the protests, however Cherry Hill was selected as the site of the first planned Negro Suburb, labelled by The Baltimore Sun, “The model Negro Village” (Winbush et al, 2015). In October of 1943, HBAC announced they would build 600 housing units for African American workers. And shortly after the war, all 600 units were converted into low-income housing.

The city–while demolishing public housing–found land that was “acceptable” for poor Black folks in the most isolated and toxic area of Baltimore. In 1950, the Baltimore City Council approved an urban renewal project which included the demolition of public housing and displacement of Blacks. The following year, in 1951, the HABC once again found reasons to continue building in the Cherry Hill area, rejecting 39 alternate locations seeing Cherry Hill as the “only politically acceptable vacant land site for Negro housing” (Winbush et al 2015). This was not an isolated event, but rather a policy designed to intentionally segregate, isolate Black people from white spaces. This was an environmentally “toxic community” built on toxic lands to house Black people; unlike other parts of the city where white flight led to segregated housing, this was “intentional segregation by design.”

In 2010, 94.7 percent of Cherry Hill residents were American African. 28.2 were unemployed (compared to 11.1 percent of Baltimoreans). 45.1 percent of families in Cherry Hill were living in poverty compared to 15.2 of families throughout Baltimore City. Cherry Hill has a life expectancy of 69 years and a Healthy Food Index score of 7.9, which is extremely low, compared to Mt. Washington/Coldspring at 28.5 (BNIA, 2018), a community with a Whole Foods Market in its borders. Over 50% of the community are renters (BNIA, 2018); most members do not control or own land in the community. There are 13 food stores in the neighborhood—two convenience stores, nine fast food/takeout vendors, one specialty food store, and one liquor store (Jackson 2019). While the Cherry Hill Town Center previously housed several supermarkets and grocery stores, today there is no full-service grocery store; there has not been a grocery store in 15 years. The space once occupied by several grocery stores is currently operated by a Family Dollar. The closest supermarket is about two miles away. Logistically, it is difficult to access transportation to these healthy foods, with relatively low car ownership and limited public transportation (Jackson 2019) and healthy food availability is very poor. Almost all of the food available in Cherry Hill is low in nutrients and high in preservatives, salt and fats . Food carry outs, corner stores and convenience stores provide most of this food5 (Jackson 2019). Structural barriers like zoning codes, transportation, and traditional economic development trends also impact food apartheid. These numbers make obvious decades of the city’s divestment from the neighborhood. As a result of this systematic disinvestment Cherry Hill is considered a food apartheid region.

Perpetual Land Insecurity and Placemaking in Cherry Hill

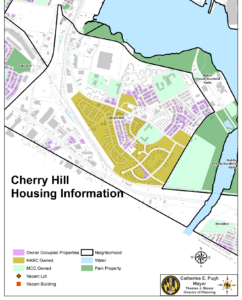

Cherry Hill’s very existence is characterized by external control and discriminatory city policies. From the founding of the community, the destiny of the residents was largely determined by elected officials, public servants, and private corporations. Anecdotes from descendants of previous occupants reveal that Black people, along with white folks, were displaced in order to create the community we know as Cherry Hill. The community, through various federal public housing projects, was developed along with a large number of Housing Authority of Baltimore City (HABC)-managed properties. This translates into over half of the housing stock and land being owned by the federal government. Since the 1990s, families living in public housing have been displaced; toxic soils (as a result of the city incinerator and landfill mentioned above) and the oversaturation of public housing have been communicated to community leaders by federal agencies as the reasoning for such actions. In addition to the city, private corporations own and manage a significant portion of the housing stock in Cherry Hill Hill (see the map).

Owner-occupied and renter-occupied housing, along with unoccupied and vacant units, make up the remaining portion of housing in Cherry Hill.

The Cherry Hill peninsula is home to a robust history of Black placemaking. In spite of the limited self-determination and control of the food economy, Black families have created social, political, and economic opportunities historically and contemporarily. The resilience, resistance, and revolutionary action displayed throughout the past eight decades marks this space as home to some of the most radical social movements in the city. The 50s and 60s ushered in the development of social and political groups for the purposes of securing and protecting community amenities prohibited merely because of race. Churches, civil rights organizations, and community associations were established as centers of community strength, mutual aid, and community organizing6 (Breihan 2003). The 1970s and 80s included community reorganization amidst demographic shifts due to policy and social changes. Environmental justice organizing took the form of a group called Interested Citizens for Equality, or INCITE, and they were aligned with the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE). The Cherry Hill Coordinating Council disavowed the upstart organizations almost immediately, claiming they were “politically motivated.” The militant politics expressed by CORE, INCITE, and other Black Power organizations threatened to burst open the city’s typically staid municipal proceedings.

Madeline Murphy authored a weekly column in the Afro American weekly newspaper, and for years defended Cherry Hill in the press, while holding city officials accountable for their promises to rid the community of the Reedbird Incinerator7 (Cummings 2021). Organizations like the Cherry Hill Development Corporation were established in order to address the increasing issues facing the community. Schools, faith institutions, youth development centers and other groups continued to support families, children, and adults in various aspects of community life. In the 1990s and 2000s, organizing efforts converged in the establishment of new housing developments, inviting current, new, and alum residents of Cherry Hill as renters and owners. Many organizations continue operations and new ones emerged to address specific needs or social problems in the community. The Cherry Hill Community Coalition was established in an effort to coalesce the efforts of all of the community organizations doing work in the community and to execute the plans formed in the Cherry Hill Master Plan. Today, Cherry Hill is one of the most organized communities in the city of Baltimore. One organization working in Cherry Hill that emerged in the 2010s was the Black Yield Institute.

Black Yield Institute Forging a New Path

“Black Yield Institute (BYI) is a Pan-African power institution in Baltimore, Maryland.” The work and mission of BYI is two-fold: 1) combat food apartheid and 2) build movement toward Black Land and Food Sovereignty. BYI’s work to combat food apartheid includes urban agriculture and food cooperative development. The movement building work of BYI includes political education, research and knowledge creation, and action network building.

According to BYI, Food Apartheid denies people the relationships with the producers of the food that they consume and the traditions that their ancestors have birthed and perfected through practice. Black people live in a state of separation and alienation from land stewardship. This type of food inequality is certainly the result of capitalism and white supremacy, which has denied closeness to many of the living systems that Black and Brown people in Baltimore and in Cherry Hill need to experience. Through the insidious human experiences within a food apartheid system, Black and Brown families are largely relegated to estranged relationships with other people and from the food and land that their ancestors intimately cultivated and stewarded. Black Land and Food Sovereignty organizing is necessary to restore these relationships and thus engage in radical intimacy. Additionally, organizing allows people to disinvest from oppressive systems that continue to disconnect us from our food sources, the land, and from ourselves. The primary goals are restoring and reclaiming relationships for the purpose of building power and establishing control of our food environments, food systems, and our own destinies.

The direct response to food apartheid is through building and maintaining power. Black Land & Food Sovereignty, which comes from La Via Campesina’s definition of food sovereignty—the right of people to healthy, affordable food and centering people’s food and land desires over that of corporations—seeks to reconnect the generational impacts of food apartheid to the land. Black Yield has taken this general concept and adapted it to include a hyper-focus on Black, African peoples and the use of ideological and practice frameworks throughout the African Diaspora and leads to power building and greater control of food and land in urban and rural contexts. The ultimate work that Black Yield Institute is doing and aims to do is to denormalize food apartheid through a humanization process that connects the people to land, cultural traditions, and foodways. BYI’s emergent praxis is restoring the intimacy between people, food, the land, and culture.

Black Yield works towards normalizing the practice of sovereignty by practicing and highlighting the significance of insourcing solutions to our problems created by imperialist practices rather than emphasizing the prioritization of outside sources of so-called help. An overall awareness of the role of self-determination in creating sustainable and healthy communities points us to the reality that waging struggle is the only way to bring about necessary shifts in the control of food, land, culture, and people.

Freedom Dreams and Policy Implications

Much of Black Yield’s political education (whether through Sankara Hamer Academy8) or the Black Food Research & Knowledge Creation scales up to influence and shape city-wide policies on land use and food access. In Cherry Hill, BYI and the larger community are organizing to create, what Ed Whitfield calls, liberated zones9 where the community can imagine and build the futures we want to see. Whitfield calls for us to “create freedom a little at a time” (Whitefield 2018). BYI is leading the charge to reimagine the use of land and the availability of culturally appropriate food for the purpose of freedom. The pursuit of Black Liberation through food sovereignty and land reparations is only possible through the activities and space that the organizers and the people create to practice freedom.

BYI is working directly on establishing liberated zones. expanding upon the food economy-work already being done in Cherry Hill. BYI’s multi-tiered approach includes investments in infrastructure for food production, retail and distribution in Cherry Hill and South Baltimore. BYI currently stewards the Cherry Hill Urban Community Garden, a 1.25 acre farm located on HABC land, and anchors the organizing for the Cherry Hill Food Co-op. By 2022, BYI plans to expand the farming operations to a six- to ten-acre plot of land, including a nursery, cultural center, aquaculture, and agrotourism. This expansion will allow BYI to create worker-ownership opportunities for workers in South Baltimore. Cherry Hill Food Co-op, a cooperative grocery store project at the development phase, will be erected and operational by January 2024, based on the project trajectory and projections. The project is currently engaged in community political education and outreach throughout South Baltimore. BYI is also engaging in community-based business planning and mapping. The next major step in 2021 is to begin a major capital campaign to fund construction, inventory, hiring, marketing, and other major aspects of the cooperative grocery store effort. The significance of this project is rooted in the fact that the community will have a grocery store after fifteen years and community members-owners of the co-op will build community wealth, while lessening the impacts of extractive economic ventures.

In terms of distribution, there are two major channels. BYI Marketplace is a community bi-monthly “pop-up” farmer’s and public market. Currently, the Marketplace is operable on the first and second Saturdays of every month. The initiative provides produce from our farm and others, while featuring other goods and services rendered by other local entrepreneurs. BYI will increase the frequency of the Marketplace as a permanent occupant of a newly renovated public market in late 2021. BYI will be able to increase their sales and access to more families as we expand the frequency of programmatic offerings and goods and services from Black microenterprises. POP Produce (pre-ordered produce) is a delivery service model that fashions logistics on a standard Community-supported Agriculture (CSA) framework. Within our model, elders and other community members can order produce from our list of available items on a weekly basis. BYI anticipates expansion of the initiative to the entire community in January 2022. BYI plans to reach over 200 unique households annually through the POP market.

Over the next three to five years, BYI is undertaking the expansion and development of enterprises that build power, provide food and ownership opportunities, and create a model of Black Land and Food Sovereignty at the hyper-local, community level. BYI’s plans are demonstrative of how community-controlled movement institutions can serve as liberated zones created to hold freedom dreams.

Black Yield has experimented with community-based participatory action research to develop targeted interventions. Their recent report, “Community Control of Land: The People’s Demand for Land Reparations in the City of Baltimore,” came out of a year and ½ of community dialogue, “listening sessions,” conversations, focus groups and a teach-in. What came out of this is: most community members believe that access to land is a human right, and that their current state of access is a violation of said right. In addition, participants across focus groups believed that access to a plot of communally owned land would create significant economic, public health, safety, and quality of life improvement potentials for their neighborhood10 (BYI 2021) In order to make Black neighborhoods matter, it became clear that city-wide investments in land reparations and tools, materials and resources for agro-ecology could drastically improve quality of life. It is also the role of government to protect residents from land speculators and predatory forms of development. Every neighborhood in Baltimore should have access to 1-2 acres of land: The city should be responsible for testing soils to determine the extent of the lots’ safety for community agricultural use, the city agencies should render no-cost land acquisition to Black communities as a form of reparations for the residual effects of redlining, and this should all be done with no strings attached (see Land Report, BYI 2020)

Instead of working against grassroots interests, this report highlights how the city could utilize its power to protect Black communities and Black people from predatory developers and land speculators and ensure long-term community ownership of land and means of production.

However, In 2021 BYI experienced an imminent threat to land security, as the farm they steward will be displaced by HABC in December of 2021. The decision to displace has been publicly communicated as a matter of compliance for The Department of Housing and Urban Development. Many community organizations have fought this and many other political debacles that have had adverse effects on community life, health, and wealth.

BYI’s land reparations report and their Black food sovereignty work resemble larger policy pushes for a Green New Deal, especially a Black and Red New Deal. Legislators like Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (D-NY) push for a Green New Deal—which is a comprehensive plan for utilizing federal dollars to transition us away from fossil fuel industry and build urban and rural landscapes of renewable energy, guaranteeing climate-friendly work, no carbon housing and free transit. Ocasio-Cortez has suggested we need a Green New Deal for public housing which includes retrofitting all ailing and environmentally unhealthy infrastructure to provide social housing for the poor. Moreover, in July 2021 Rep. Jamal Bowman (D-NY) introduced legislation for a Green New Deal for Public Schools which includes some of the same proposals for ailing schools. This would put $1.4 trillion of federal dollars, redirecting $446 billion of grant funds, over 10 years toward decarbonizing and retrofitting the nation’s K-12 schools, particularly in high-need and socially vulnerable areas where schools represent another social and environmental hazard especially in poor communities of color. Bowman’s three impact areas are health and environmental equity, educational equity, and economic equity. The jobs will be given to local residents from construction to retrofitting to educating. These retrofits will turn schools into neighborhood resiliency hubs, making them key nodes of overall green community infrastructure, and of zero waste infrastructure.11 It is within this climate of progressive “squad” members proposing a Green New Deal that perhaps youth movements like Free Your Voice (an environmental justice youth movement in South Baltimore) can serve as a kind of model for how to do this engaged learning tied to environment and climate policy work.

What is clear from all these policy pushes is that the ideas and the vision for change must emanate from Black and Brown communities and from the grassroots. The policy at the city, state and federal level must be defined, shaped and even implemented by Black and Brown organizers—As Indigenous scholar and activist Nick Estes writes, “Red Deal, focusing on Indigenous treaty rights, land restoration, sovereignty, self-determination, decolonization, and liberation. We don’t envision it as a counter program to the GND but rather going beyond it—‘Red’ because it prioritizes Indigenous liberation, on one hand, and a revolutionary left position on the other12.” (Estes 2019) The Red & Black New Deal13 is an initiative that takes action to mitigate the impact of the global climate crisis on Black and Indigenous Lives. The fight for climate justice must be a vision emanating out from Black and Native visions of liberation to claim rights to water, energy, land, labor, economy and democracy.

The Green New Deal has the potential to connect every social justice struggle—free housing, free health care, free education, access to land and to healthy foods, green jobs—to climate change. However, if it is not guided by and coming out of the distinct historic experiences of Black and Brown communities, then, it will simply be co-opted by larger white NGO’s and white-led environmental organizations. Black Yield Institute and other Black-led organizations fighting for land reparations and food justice can be a model as we push for policy changes at state and federal level. For we are in a moment of climactic crisis, it is clear from the most recent IPCC report that we need action now. Instead of a top-down vision, we propose a bottom-up solution where federal funds support already-existing visions of freedom dreams, agro-ecology, land reparations, investments in education, and solidarity economics. The time is now and never has it been more urgent for Black and Brown communities to own the land, produce their own food, and create wealth that circulates back into their communities.

1 Lawrence Brown, Two Baltimores: The White L versus the Black Butterfly, June 28, 2016

2 Cherry Hill is a community located in the southern section of Baltimore, Maryland. The area is generally bounded to the North by Waterview Avenue/Hanover Street, Southeast by the Patapsco River, Southwest by the City boundary and West by Baltimore and Ohio Railroad. The area is composed of census tracts 2502.03, 2502.04 and 2502.07. The community is located south of the Inner Harbor/central business district of Baltimore City (Morgan State Report)

3 Jaisol Noor, et al, Battleground Baltimore The Fight for Green Spaces, July 2, 2021.

4 Raymond Winbush et al, A Comprehensive Demographic Profile of Cherry Hill Community in Baltimore City, Morgan State July 2015.

5 Eric Jackson, Cherry Hill Food Co-op Readiness Report, 2019.

6 See John R. Breinham, Cherry Hill a Community History, Loyola College in Maryland 2003.

7 See Daniel Cumming, All That’s solid melts into Air: A Suburban Crisis, Toxic Incineration and the Wastelanding of South Baltimore 1943-1983, Dissertation, NYU 2021.

8 The Sankara Hamer academy is Black Yield’s school of political education with a focus on Black land and food sovereignty. The Academy entails monthly educational gatherings; community and organization-requested workshops; and a 15-week leadership development course.

9 Ed Whitefield, What must we do to be free? On the building of Liberated Zones, Journal of Social Equity 2(1): 45-58, 2018.

10 BYI, Community Control of Land The People’s Demand for Land Reparations in Baltimore City, March 2021.

11 Jamal Bowman, A Green New Deal for Public Schools, 2021 https://bowman.house.gov/_cache/files/2/9/297d4603-cabd-43bd-9ab0-044c21be7f7a/F58C35F28FBC115F0D531D7D185C9E01.gnd-for-public-schools-act-final.pdf

12 Nick Estes, A Red Deal, August 8, 2019.

13 For more on the Red, Black and Green New Deal, See https://redblackgreennewdeal.org/

Leave a Reply