[This article, originally published in Spanish by

desInformémonos, was translated by

Global Justice Ecology Project. Steven Johnson coordinated the translation and wrote the following introduction for publication by

New Politics.]

The elections in Ecuador earlier this year continue to inspire international debate among competing left currents over lessons to be learned and may serve as a revealing window through which to analyze the class interests of Latin American progressive movements stemming from the “Pink Tide.” The article challenges a widely circulated interpretation of the events (see, e.g., this DSA-sponsored forum), and will inform ongoing debates in North America and elsewhere over the meaning of “solidarity” and with whom and how that should be expressed. While the narrated episode concerns the candidacy of the Indigenous leader Yaku Pérez, the article is not an assessment of that candidate’s merits or demerits (indeed, the article concludes by directing focus away from electoral politics), but uses the lens of these events, particularly, the progressives’ desperate attacks against Pérez between the first and second rounds of the elections, to shine penetrating light into the nature of the Correist movement and their progressive allies worldwide and their fateful actions in alienating and persecuting the Indigenous movements that first brought them to power.

It is striking the fury with which defenders of the South American progressive governments, from different countries, devoted themselves to biased criticism and mudslinging against an Indigenous presidential candidate during a critical moment of the Ecuadorian election process earlier this year. In the first round of the Ecuadorian elections that took place on February 7, 2021, Yaku Pérez, of the Quechua-Cañari people, with a long history in the defense of water against mining projects in his region, and a leader of the Confederation of Indigenous Nationalities of Ecuador (CONAIE) and of the Confederation of Peoples of Kichwa Nationality (ECUARUNARI), received 1,800,000 votes (exceeding 19%) and fell short of second place by just a few thousand votes. The result, which meant that the banker Guillermo Lasso, rather than Pérez, would face Andrés Arauz, the candidate of Rafael Correa, who is exiled in Belgium, in the runoff election of April 11, was contested without success in the courts.

This episode can be read as emblematic for understanding the limits and dilemmas of a politically weakened progressivism that needs to face up to the costs of the kind of politics it implemented.The social media campaigns against Yaku Pérez came into play while the vote count from the first round was being determined and for several days the Indigenous candidate remained in second place. When the count was concluded, the banker Guillermo Lasso, of the political party CREO, Creando Oportunidad (Creating Opportunity), reached second place. This was thought to be a more favorable result for the Correist candidate, Andrés Arauz, of the political party UNES, Unión por la Esperanza (Union for Hope), who had received the most votes, 32%, in the first round.Yaku Pérez is an attorney and has earned advanced degrees in the management of watershed basins, environmental law, Indigenous justice, and criminal law, and resigned his position as prefect of Azuay Province in order to run for president. He was also jailed several times in connection with water defense struggles, was kidnapped by a Chinese mining company, and suffered the expulsion of his partner, of foreign nationality, also an activist, after a mobilization during the time of Correa’s government.

Juan Carlos Monedero, a politician from the Spanish political party Podemos with political ties to Latin American progressivism, participated in the February 7th elections in Ecuador as an election observer. In an interview with teleSUR the day after the election, Monedero set the tone for what would be heard for several days. He considered Pérez’s candidacy to have been manufactured in a lab, financed from abroad. He spoke of a “false candidate” and “fake Indigenous people”, while he defended Arauz as the candidate who would enable Ecuador to “take its rightful place in the world again”. This distrust concerning Yaku Pérez’s Indigenous identity and his candidacy arises from Monedero’s notion that the adoption of an Indigenous name could only be intended to deceive, and out of ignorance of the Indigenous world he compares it to adopting a new name when entering a Catholic religious order. For an aggrieved Monedero the anti-mining struggle is not genuine either, and he denied that Yaku Pérez has any collective support or a plan for the country.

Monedero warned on TV of a plot to prevent the election of Andrés Arauz. This plot consisted of seeking to replace Guillermo Lasso with Yaku Pérez in the runoff election since the latter was thought to have greater possibilities of defeating Arauz, the candidate who replaced Correa, who could not run for either president or vice president due to his conviction on corruption charges. The operation would be supported by the United States and carried out by means of favorable coverage in the media. It is strange to see this analysis coming from one of the founders of Podemos, which became a phenomenon in Spanish politics exactly in this way, with extensive media coverage of a candidate who would create a space beyond the prevailing tradition of polarized politics. Within a few days progressive analysts and political actors would carry out a smear campaign against Yaku Pérez, which they only dropped once the banker Lasso came out ahead of the Indigenous candidate in the vote count, and there was no longer the threat of a difficult race against Pérez. Another Spaniard close to the South American progressive governments, Alfredo Serrano, of the Latin American Strategic Center of Geopolitics (CELAG), declared, “We can say that Yaku is a non-progressive candidate who managed to get part of the progressive and Indigenous vote“, and also denied that the votes really reflected support for Pérez himself. Downplaying Pérez’s own strength as a candidate, he wrote that these votes could have been for any other Indigenous leader who ran, while failing to apply the same line of reasoning to the Correist candidate.

For some days the goal was to to deconstruct Pérez’s candidacy, whether to prepare for a runoff race against him or to stop the electoral results from being questioned.The high number of votes for the Pachakutik Plurinational Unity Movement (MUPP), the political arm, founded in 1995, of the now-divided Confederation of Indigenous Nationalities of Ecuador (CONAIE), is explained by the growth of the Indigenous movement in the Amazon and mountain regions of the country, and undoubtedly reflects the political impact left by the eleven days of blockades and protests in October 2019. Begun in protest against an increase in fuel prices ordered by President Lenín Moreno, with a decisive role played by CONAIE, the protests voiced the concerns and discontent which was also manifested by a million spoiled ballots. In the October uprising CONAIE had made clear that its rejection of the government of Lenín Moreno would not mean a rapprochement with Correa, who during his time in office criminalized hundreds of Indigenous leaders, and that opposition which extends across the Correa/anti-Correa divide was expressed in its choice of Yaku Pérez.

These first-round election results were a defeat for President Lenín Moreno, who after breaking politically with Correa, to whom he was vice president and the successor candidate, ended up on the sidelines due to pressure from the streets. But it was also a disappointing result for the Correists, who had hoped to win in the first round, capitalizing on the disrepute of the current government. The traditional right, in a front headed by Lasso, was also weakened, affected by the mishandling of the pandemic in Guayaquil. For Pachakutik it was a victory which allowed them to take up the October 2019 anti-neoliberal struggle again, as well as advance its anti-extractivist agenda that seeks to give rise to a different model of development for the country.Alicia Castro, whose background is in the Peronist renewal union movement of the 1990s and who was formerly the Kirchnerist ambassador to Venezuela and the United Kingdom, joined the smear campaign against Yaku Pérez and asked, via Twitter, “Who is the candidate @yakuperez who wants to upset the elections in #Ecuador, allied with @Almagro_OEA2015; he can confuse some misinformed people as an ‘environmentalist’, ‘Indigenist’, or ‘New Left’. But he is a fraud. Nothing new under the sun, since La Malinche.”

Questioning people’s self-identification as Indigenous is a common part of the usual strategies of colonial dispossession. The argument of “fake Indians” is used to promote expansion of the agricultural frontier into Indigenous territories all over South America, and to defend development projects that threaten their water and ways of life. Allied with the power of agribusiness and large-scale mining interests, the Correists know that Yaku Pérez and CONAIE are an obstacle to the predatory model with which they govern. The election attacks, with charges of plots that proved to be groundless, should be understood, then, as a continuation of the strong repression and harassment against Indigenous organizations and territories that took place in the Correa years.

Persecution by progressive South American governments against leaders of Indigenous movements and environmental struggles is nothing new on the continent. Nor is the greater comfort that progressives feel in running against right-wing candidates, as they wage dirty campaigns against possible alternative candidates in the first round of a presidential election. But that an Indigenous candidate would challenge a progressive candidate from the left is a new phenomenon in Ecuador as well as in the rest of Latin America. The new parliamentary left that looks for institutional space in the region also participated in the campaign against Yaku Pérez. This kind of left which brings together dissidents, “critical support”, new leaders that run in presidential elections in Chile and Peru, typically stays under the wing of the political influence of progressives or leftists who were in or remain in government, thus reinforcing its political influence and resistance to change. Timid criticism of a dependent model that makes life unviable is only made behind closed doors and serves to portray the economic model and the consensus views of those in power as the only alternative.

The hope that Pachakutik would reach second place unified a divided Indigenous movement. Conflicting leaderships and visions were divided over to what degree class should be emphasized, openness to alliances with the mestizo sectors, willingness to engage in confrontation in the streets, and which individual leaders to support. At this juncture, however, they set out to mobilize in defense of the vote, while still maintaining their political differences. Facing a weak right wing, and a progressivism whose support had eroded and that is unable to raise a debate over the model of development in the whole region, the various tendencies of the Indigenous movement and of the critical non-developmentalist left display tendencies, contradictions, and agreements which truly matter as a possible step forward in South American politics. In these debates some proposals of Yaku Pérez are criticized by Leónidas Iza, who played a leading role in the October uprising, and other leaders. It is a necessary debate in which progressives did not take part, as they threw themselves into a campaign marked by a logic of electioneering and of polarization with the right that would leave no room for anything else.

The Pérez campaign challenged the election results with technical data, asking for a recount of 20,050 observed voting records (out of a total of 39,000). The Electoral Court only agreed to review 31 voting records, which was later reduced to 28, and with which the Pachakutik vote was increased by 612 votes, confirming that votes had been wrongly attributed in the initial count to candidates who were below third place. Based on this discrepancy there were mobilizations, and an appeal was presented which was not heard in the Court and was subsequently also denied by the Electoral Commission. Alarms were sounded among the progressives when, with the vote count undetermined, a meeting was held with Lasso to jointly request a recount in some provinces, a meeting which did not end up settling the matter. It was Lasso who abandoned the recount request once his slight advantage was established.

Yaku Pérez denounced fraud aimed at keeping him out of the runoff election, presenting indications of irregularities. Progressives considered this claim to be part of another fraud, one against Arauz, and that risked causing a constitutional crisis, discrediting Pérez once again, whose presence in the game would be merely a maneuver by the right and the United States to stop the Correists. As progressives from other countries also enter the fray, a certain short-circuiting manifests between legalistic, militant, and fake news lines of argument and state authoritarianism: First they used their own power to criminalize leaders or militarize Indigenous territories to impose mining projects, as in the Shuar and Sarayaku cases, and later we see them trying to raise public sympathy for themselves in South America as the victims of “lawfare”.

If, following the CLACSO researchers Adoración Guamán and Soledad Stoessel, we understand “lawfare” as “a widely used tool that combines media manipulation of public opinion, physical and legal repression, imprisonment and criminalization of the political opposition”, we see that this is exactly the situation that the Indigenous movement faced with Correa in the defense of their territories, and also Yaku Pérez in the smear campaign that denied his Indigenous identity and the legitimacy of his struggle and election to high office. But the researchers are applying the concept to the persecution of Correa and are even joining the wave of suspicion against Yaku Pérez by using another common argument in the media deconstruction that the candidate suffered, that depicts him as isolated from an Indigenous movement that the progressives imagine to be aligned with the Correists.

The dirty campaign also denied his environmentalism and linked him to the right and to imperialism, accusing him of being a channel of U.S. interventionism. In the days after the election, progressive militants prepared to denounce a coup, as they did in Bolivia in 2019 and in Brazil in 2016. Latin American progressives saw Yaku Pérez as an ally of Luis Almagro, the Secretary General of the Organization of American States (OAS), which played a part in tipping the scale toward the resignation of Evo Morales in 2019 when it recommended that the elections be held again after being invited by Morales himself to observe the elections. The philosopher Luciana Cadahia, a Correist sympathizer, denounced in a public Facebook post a pact between Yaku Pérez and the banker Lasso that would be a “little Hegelian trick” orchestrated by Almagro, and with the help of the press, in which the “supposed” Indigenous movement, acting out of an accord with the oligarchs, would find a sophisticated way to defeat Arauz by forming an alliance between the second and third place candidates in the election, while avoiding the “high price” that Almagro had to pay for his involvement in the Bolivian crisis.

Faced with the strength of the Yaku Pérez campaign, another approach would have been to open up a political dialogue about the model of development and the agenda of October 2019. In an about-face to the dirty campaign, and showing how unfair the questioning of Yaku Pérez’s left and Indigenous credentials was, after the election Andrés Arauz himself stressed on his Twitter account: “Progressivism + Plurinational Unity + Social Democracy = 70%. On February 7th, the Ecuadorian people already won”, adding together the Correist votes with those of Yaku Pérez and also those of the fourth-place candidate, Xavier Hervas of the Democratic Left Party. Far from denying the anti-neoliberal stance of his opponents, and even drawing near to them to gain their voters and presenting the banker Lasso as the principal opposition to Correism. But it is doubtful to what extent, beyond elections, anti-neoliberal and environmentalist agendas could be advanced by the progressives.

The ambiguous nature of this game stands out as different faces of progressivism are displayed, on different occasions, to achieve the objectives of what is, nevertheless, one and the same movement. Before the election the Correist movement was focused on defending against an attack that involved the Attorney General’s Office of Colombia, which claimed that evidence had been found on the cell phone of a captured soldier of the Army of National Liberation (ELN, by its initials in Spanish) showing that the Colombian guerrilla organization had funded the Arauz campaign. The damaging press coverage that followed incited the mobilization of institutional progressive networks in response. The Puebla Group, which brings together ex-presidents, academics, and legal experts (among others, Andrés Arauz and Rafael Correa) and participated as election observers, denounced an attack on democracy.

With the signatures of Axel Kicillof, Guilherme Boulos, Daniel Jadué, Gustavo Petro, Pablo Iglesias, and Verónika Mendoza, the “Espacio Futuro” (Future Space) forum, which forms the nucleus of a younger generation of progressive leaders, issued a declaration opposing any change in the dates of the elections, thus joining the campaign that dismissed, without knowledge, the charges of irregularities that the Indigenous candidate was bringing before the Ecuadorian Electoral Court and Commission. In a political game in which they appeal to the rule of law when it serves their purposes and cast themselves as observers of the elections to protect democracy, they did not pay the least attention to the evidence of irregularities that was presented. The tactic is to use academically prestigious cadres to broadcast talk of a coup, which has, in many cases, justly defended progressivism, but then maintain a partisan silence concerning similar practices within their own camp.

Against the Indigenous movement a very different face appears, involving criminalization, pursued not by democratic legal argumentation under the rule of law, but involving persecution by police and legal harassment, not to mention the very assaults on territories against which Yaku Pérez and CONAIE resisted. The campaign against Yaku Pérez, which is reminiscent of Correa’s defamatory TV broadcasts against the Indigenous leader and his partner, Manuela Picq, also an activist, spread over social media when Pérez appeared to be headed to the runoff election and the progressive movement imagined a new version of a “new kind of coup”. Fears already awakened by the machinations of the right (which indeed exist) mobilized a media machine that, arrogantly and rapidly ceased to distinguish its institutional mandate as a media organization from a project of power that, in the name of the people’s interests, and faithful to the style of the statist authoritarian left, is unable to cope with differences.

Correa’s Citizen Revolution carries tensions and ambiguities that are expressed, as in the MAS party in Bolivia and other places, by the international alliances that support them. In contrast to the claims of lawfare that unite Correa and Cristina Kirchner to the legalist defense with which the Workers Party (PT, by its initials in Portuguese) responded to the political trial of Dilma, the very different accusations against Yaku Pérez coming from media associated with Cuba, Nicaragua, and Venezuela tend to allege collaboration with imperialism or the right.

Against this narrative that painted Yaku Pérez as a supporter of South American coups, and as a potential instrument of a U.S.-backed coup against Correa, stands the fact that on June 12, 2019 Yaku Pérez declared his support for Lula da Silva as a representative of the Andean Coordination of Indigenous Organizations (CAOI, by its initials in Spanish). In the vigil held across from where the ex-president was detained pursuant to a warrant issued in connection with Operation “Lava Jato”, he declared, “I am here to support you, Lula. We are with you, and we will not rest, we will be in resistance.” Concerning international investment, Pérez complained about the aggressive attitude of China in connection with extractivism and human rights violations. Concerning the United States, however, he said that “the hawk is a hawk”, but spoke positively about some policies of Biden.

The automatic alignment of South American progressives against an Indigenous candidate is quite striking if we look at the positions that the Correists are defending, not only concerning socio-environmental issues. Three days before the elections, at the close of Correa’s campaigning efforts from exile, he appealed to conservative voters by criticizing Yaku Pérez for his position approving abortions up to three or four months of pregnancy, referring to the position in terms of “hedonistic abortion” and “because I carelessly dedicated myself to a frenzied sexual activity, I can just get rid of the child without meeting any requirement.” Rafael Correa went so far as to threaten to resign in 2013 if the legislature approved abortion, and proposed expelling the women who supported this position from the party. His conservatism goes beyond the war that was declared against Indigenous peoples for their natural resources and can also be seen in the push for the Family Plan, whose recommendation for sex education was “abstinence and values”.

A tweet by Yaku Pérez from November 2016, recirculated by Correa and others when Pérez was contending for second place, evidenced Pérez’s anti-corruption stance, saying: “#Corrupción is what brought down the governments of Dilma and Cristina; now what’s left is for @MashiRafael and Maduro to fall. It’s only a matter of time.” Naturally, those today who criticize the lawfare against Cristina Kirchner or against Correa himself, or who see the fall of Dilma and Evo as operations orchestrated from Washington to impose right-wing governments, will be inclined to distrust Peréz.

But anti-corruption stances, however liberal they may seem, are not just banners used by the right against progressives. It is almost mandatory for any new left, as it was for Podemos in Spain, which despite political ties stopped defending governments like those of Maduro and Ortega, or new lefts in Chile and Peru, when progressivism came to power. Nor is opposition to Dilma Rousseff unusual, given that she approved anti-terrorism laws, criminalized activists, and allied herself with conservative pastors, agribusiness leaders, banks, and large mining interests, even ceding government ministries to these sectors. Like the highway in TIPNIS in Bolivia, and the petroleum in Yasuní National Park in Ecuador, Dilma is paying the political cost of having authorized Belo Monte, a mammoth and badly conceived dam, whose incalculable harms are already being seen, which financed her campaign and is emblematic of the environmental and ethnocidal destruction that is taking place in the Amazon region. In a recent video, referring to the popular June 2013 protests in Brazil, Dilma Rousseff referred to talks with Putin and Erdogan in which her political downfall was interpreted as, more than a coup or lawfare, a hybrid war promoted by the North American power.

Only out of complete ignorance of the dynamics of Indigenous organizations of the last decades is it possible to characterize NGOs as being able to manipulate Indigenous peoples into mobilizing to oppose projects that, in fact, leave their territories polluted with cyanide or without water. A dirty campaign can be spoken of because its promoters are well aware of the history of the Indigenous organizations (with which progressives were allied) as well as the role of Yaku Pérez and CONAIE. The discourse about NGOs influencing Indigenous groups to attack national sovereignty is nothing more than a campaign to defend economic and political interests, favorable to large-scale mining and unrestrained oil exploration. It is exactly the same discourse used by Bolsonaro and the Peruvian or Colombian right wings to encroach on the Amazon.

On the other hand, tweets of little impact from years ago were recirculated in an effort to undermine a candidacy, denouncing a coup. But in reality, this shows how worried they were to face a more competitive candidate in the second round who knew how to put his finger in the wounds of progressivism’s shortcomings and who directly represented the social movements. What remains ignored is the political debate that has been taking place ever since the progressives made clear their developmentalist agenda and went on the offensive against the historic Indigenous organizations throughout the region. A more Bolivarian line of deconstruction of Pérez’s candidacy, even by movements aligned with the Chinese government, is seen through an article published in the website of the Landless Workers’ Movement (MST, by its initials in Portuguese) of Brazil, summarizing an article by the North American journalist Ben Norton, signed by the editors, with the title “The Ecosocialist Candidate of Ecuador: Indigenous and a Supporter of Coups d’état in Latin America”. From the Bonifacio Foundation, tied to Aldo Rebelo, ex-minister of Lula and Dilma from the Communist Party of Brazil (PCdoB, by its initials in Portuguese), it was affirmed that Yaku Pérez was a trojan horse of foreign powers. The article states that foreign interests are being defended under identity, environmentalist, and Indigenist banners, by means of contact with NGOs. In the Cubadebate portal, Atilio Borón would take the same approach, declaring that the Indigenous candidate’s Indigenous and left discourse was nothing more than a ploy to serve imperialist interests.

On Kawsachin News, an English-language news service of the federations of coca producers of Chapare, Ollie Vargas accused Yaku Pérez of using fake news to incite crimes against Venezuelan migrants in Ecuador. The Indigenous candidate had referred to allegations of intervention by “Venezuelan brothers” in a conversation that went viral, without us being able to know the context, in a short video which associates him with the anti-Venezuelan and xenophobic discourse of Lenín Moreno. The popular Brazilian YouTuber Jones Manoel associated Yaku Pérez with Ernesto Araújo, Bolsanaro’s Minister of Foreign Affairs, of the extreme conservative right wing, and other political figures in Brazil. The attacks, slanders, and fake news that circulated concerning Yaku Pérez reflect the position of the recent revisionist wave of Stalin. Accordingly, José Correa Leite has likened them to the Stalinist operations of “amalgam” in the 1950s. Progressives who are in government or who are struggling to return employ every kind of resource, with a wide spectrum of politics and discursive styles.

This line of accusation, which must be understood in the framework of a heated communications war in which imperialism, Communism, and Nazism are common currency, was based on the tendentious construction of Ben Norton, who in his blog criticizes postmodernism and anarchist, environmentalist, and primitivist currents, and depicted the Indigenous candidate as a coup supporter backed by the United States. A photo with the United States ambassador taken while carrying out official functions as Prefect of Azuay Province, the tweets concerning displaced South American leaders, and a curious combination of arguments about the Pachakutik Party and the Indigenous movement. It is striking how, on the one hand, Yaku Pérez is depicted as a leader who is isolated from the rest of the movement, while, on the other hand, funds of Third World aid from North American foundations sent to the Indigenous movement are presented as proof of his role in service to the United States, without specifying any details about these funds or showing any direct link to Yaku Pérez.

An open letter criticizing Norton’s article and another article from The Jacobin magazine, signed by academics and intellectuals such as Isabelle Stengers, Arturo Escobar, Miriam Lang, and Alberto Acosta, “Stop Racist and Misogynist Attacks on the Emergent Indigenous, Eco-Feminist Left in Latin America, and Address the Crisis in Today’s Ecuador”, led to the immediate removal of Ben Norton’s article by the North American left publication Monthly Review. The progressives’ double game short-circuits as their institutional behavior and rhetoric contradict: In the most recent electoral contests in Brazil, Argentina, Bolivia, and now Ecuador, in order to avoid problems with the justice system and opposing votes, they have chosen to back moderate and liberal candidates (Haddad, Fernández, Arce, and Arauz). But when it comes to these social media quarrels and not actual governing, they strike a more radical Bolivarian, Leninist, and nationalist tone.

The letter, signed by dozens seeking redress, rightly seeks to defend Yaku Pérez and his partner against the misleading attacks by framing the discussion in its real terms: state-developmentalist progressives, who combine populist and liberal faces, seeking to attack an anti-extractivist left that expresses the Indigenous position in the conflicts of the Correist years, as well as the position of other progressive banners such as women’s, plurinational, and LGBT rights which the Correists either did not know how to represent or abandoned. But for Ben Norton in his article, environmentalist criticisms against progressives are just marketing spin. With reports from Venezuela and Nicaragua, as well as Ecuador, the article depicts the United States as “desperate” to avoid the “socialist wave” that spread through Latin America in the first decade of the 21st Century, and found in Yaku Pérez a “perfect tool”.

In another letter, the Indigenous leader is presented as a candidate who “fights against the neoliberal offensive while breaking from the vices of caudillismo and the systemic corruption of the old authoritarian left, and challenges, in the name of life and land, the serious limitations of the extractivist development model”. This letter denounced the misleading and abusive social media campaign and was signed by Marina Silva, who experienced a severe dirty campaign herself when she ran against Dilma Rousseff in the 2010 and 2014 elections. Latin American intellectuals who suffered media lynchings for their criticism of the Bolivian and Venezuelan governments, such as Rita Segato and Maristella Svampa, also signed the letter.

In one of Yaku Pérez’s tweets quoted by his detractors, he compared the policy of intervention by Correa in CONAIE Indigenous organizations with Evo Morales’s treatment of CONAMAQ, the Confederation of Allyus and Marqas of Qullasuyo. In both cases organization headquarters were invaded, and efforts were made to create parallel organizations in favor of projects of territorial destruction, with co-optation or buying-off of leaders with state benefits. The tweet also compared the case of Yasuní in Ecuador with that of TIPNIS in Bolivia. In the case of the former, Correa opened up oil exploitation in the Yasuní National Park after a failed appeal to the world for money to protect the park from such exploitation, which Correa initially argued would be harmful. It was in this spirit that Article 71 of the Constitution approved in 2008 introduced the legal framework of the Rights of Nature, and although attempts are made to disguise the fact, Correa’s break with this agenda is undeniable.

TIPNIS was a turning point in Bolivia, in 2011, when the government of the MAS party pushed a campaign and political move to build a highway that would run through the largest national park and Indigenous territory of the country, with opposition from the historic Indigenous movement that was brutally repressed. In February 2021, as campaign manager for the regional elections, Evo Morales offered to continue the construction of the highway in exchange for votes for his candidate in the Department of Beni. In his tweet, Yaku Pérez compared Correa with Evo Morales with respect to several common characteristics: “Both ran for re-election, authoritarianism, machismo, extractivism, and populists.” These stances are consistent with the position of the Indigenous movement in the continent and are not a position taken with elections in mind.

In a similar dispute, García Linera spearheaded the Bolivian government’s criticism of the Indigenous movement and the NGOs that accompanied the Indigenous struggles that brought the MAS party to power and in which he himself had been an advisor. The line of argumentation that converges with that of the military and the Latin American conservative right, in saying that the Indigenous are playing for foreign interests, dishonestly mixed foundations tied to the North American power establishment with NGOs which provide militant and legal support to Indigenous people. As we see in the government of Bolsonaro, presenting Indigenous people in favor of agribusiness or creating pro-government Indigenous organizations, like in Bolivia. One of the accusations that Ben Norton made against Manuela Picq was precisely to mention that she denounced the ecocide of the Bolivian forest fires of 2019. According to Norton, she thereby helped to pave the way for the coup. In reality, she helped to denounce how, with decrees in favor of forest burning, obtained by powerful agribusiness interests allied with the MAS party, the government was incentivizing deforestation, just as it happened in Brazil where this was criticized by progressives.

On the one hand, the Puebla Group, Espacio Futuro, and the Progressive International, with social-democratic or progressive heads of state and other political actors, reject maneuvers like those of the Colombian attorney general, with sensitivity to the disputes that took place in the Electoral Court, and sought to prevent the recounting of votes. On the other hand, the campaign of character assassination against positions which in reality ought to be debated; media lynchings and personal attacks like those which the MAS party carried out against Gualberto Cusi, the Aymara judge who won the most votes in the 2011 direct election to the high courts and was dismissed under pressure from the government; as Rafael Correa routinely defended extractive exploitation, framing protests as a negative phenomenon by means of anti-terrorism laws, as did Bachelet with the Mapuche.

There is no way to correct or soften these maneuvers that are carried out frequently at different scales, and they are indispensable elements of a type of political construction that should raise concerns among their honest supporters. Against the eternal patience of the “critical left”, one wonders how many outrages are necessary to understand that the defense of extractivism is a top political priority, even though it involves violating rights and breaking with Indigenous peoples. In the end, the calculation that considers it strategic to maintain popular support through state policies that are detrimental to respect for Indigenous territories always prevails. It is also by this logic that the February 7th elections worried progressives. The rivers of oil money for public policies during the Correist years, and the marketing campaigns with much more money than the Indigenous movement, were not sufficient to allow electoral victory by an ample majority that would give legitimacy to the policies of this political project. It is there that the strength of an uprising such as that of October 2019 should be considered.

Raúl Zibechi is right when he says that “popular insurrections do not fit in the ballot box”, observing how, even as much as the October uprising was a watershed moment in recent history, expressing the resistance of rural communities and medium-sized cities, the ballot boxes do not change the balance of forces of a parliament dominated by support for extractivism and that does not question the neoliberal model. In her Facebook profile, Alejandra Santillana assesses after the elections that, “The streets and the construction of organized social fabric continue to be a determining path for what happens on the electoral plane. Imagining a feminist, popular, Plurinational, peasant project continues to be a pending matter that will not be resolved solely by dialogue with the state, our entry into it, or institutional reforms”.

Once the matter of the need to reject a dirty campaign is clear, it is pertinent to discuss the differences concerning Yaku Pérez’s proposals that generated internal opposition within the CONAIE Indigenous movement, and the different strategies of confrontation and dialogue that also created differences during the government of Lenín Moreno. The protests experienced in several Latin American countries before the pandemic remain latent and open up a debate that does not fit within the restricted parameters of the right vs. the progressives.

Criticism of the legal harassment of progressive leaders, and the advance of the right in the region, should not mean ignoring the contradictions and the conflicts of anti-neoliberal, Indigenous territorial, and class struggle that will mark the period that is emerging, beyond the limits of progressivism. The extreme right is growing in the region, in fact, because the progressive governments joined the political class which the majority see as disconnected power elites. Leftists of order, who fit comfortably in the realm of an authoritarian state, cannot propose another model of development even if, on some level, they understand the legitimacy of the Indigenous struggles.

As a supporter of the Correists, Valeria Coronel acknowledges that “Arauz would have to be much more emphatic that his agenda is that of the October protests, would have to get closer to the Indigenous movement and break down the barriers that were established at some point between Correa and the Indigenous movement”. This does not seem possible, and in the different countries there were many efforts on the part of the State to get closer to the Indigenous leaders. In the aforementioned text by Guamán and Stoessel it is stated that, “The Ecuador that today is expressed in the ballot boxes has shown its willingness to overcome said polarization [Lasso/Correa]. This reveals the urgency of renewing public agendas with a more progressive element in the area of rights (sexual, reproductive, associative, union, and citizen participation) and concerning the ecological question.” But is that really possible for the Correists who persecuted and imprisoned Indigenous leaders, and who seek to reach conservative and religious audiences with talk of hedonistic abortion just a few days before the election?

In an overview of current Latin American politics, Claudio Katz distinguishes between moderate and radical progressives, the moderates in the Brazil of the PT and in the “latecomer progressivisms” of Mexico and Argentina today, and the radicals in Bolivia and Venezuela, though there are questions concerning the successors of Chávez and Morales. Katz advocated voting for Arauz, as the only alternative that the Indigenous movement should get behind in the runoff election. He admits that the statements of Yaku Pérez in the 2017 elections, in which he declared, “I prefer a banker over a dictator,” and which from a binary logic is read as supporting neoliberalism, is a consequence of the “very intense conflict”, with the government insisting on expanding mining extraction, and that included more than 500 prosecutions against Indigenous leaders. But he returns to the lap of progressivism whose radical and moderate faces appear to be two moments of one and the same classic rhetorical game in the nationalisms of the 20th Century, always closing ranks with the defense of order of a single project of power. This position flows out of his characterization of the Indigenous movement in two aspects, one that is oriented to class, which could converge with the Correists, and the other that is “ethnicist”, of Yaku Pérez, with corporate demands, suspect links to NGOs, and echoes of neoliberal ideology. Katz also suggests that the ethnicist current could bring bloody ethnic conflicts like those of the Balkans, the Middle East, or Africa to Latin America, citing analysis along these lines by José Antonio Figueroa.

Together with progressives that use legalistic denunciation and make accusations of collaboration with imperialism, “critical” progressives close ranks under the impossible hope of a rapprochement with those actors whom they persecute and seek to destroy through media attacks. The solution of Katz and others points to Bolivia, where “the leaders of the MAS party introduced the plurinational State, respect for the languages and customs of the communities, and the proud recognition of the Indigenist tradition”. For them it is the incorporation of the Indigenous agenda in order to be able to continue with the agenda of development. When followed up with political actions, this incorporation can only mean intervention of the State in the Indigenous movement in order to divide it. It means clearing the path of elements of resistance and struggle against the extractivist model, while conceding merely cosmetic reforms, and continuing to pursue the model of private or state-run businesses exploiting natural resources, while lacking the strength and hegemonic legitimacy that progressives in Latin America today know they have lost.

In the end, the Correists’ strategy of mud-slinging and co-optation proved unable to return them to power, because the Indigenous movement resisted it, calling for voters to cast spoiled ballots in protest. Between the first and second rounds, the Correists engaged in a fierce campaign to divide the Indigenous movement and to win the support of what leaders it could. After the congress of CONAIE approved a call to cast spoiled ballots, its president issued a statement supporting the Correist candidate. The Indigenous movement was thus divided into two positions: spoil the ballots (the majority position, backed by the movement’s collective decisions), and vote for Arauz. Though falling short of the majority needed to legally invalidate the elections, the number of spoiled ballots was the highest in the nation’s history, 16%. This contributed significantly to the banker Lasso’s upset victory over the candidate of Correa on April 11, which, in turn, has inflamed renewed Correist resentment towards the Indigenous movement, which they blame, rather than their own long history of betrayal, co-optation, and persecution against the Indigenous movement, for their candidate’s defeat.

The Correist stances were echoed in social media by progressive militants throughout Latin America. The dirty campaign of the first round of the elections quickly gave way in the second round to traditional progressive rhetoric against neoliberalism, banks, imperialism, etc., framed in terms of the age-old struggle of Good vs. Evil. But the ferocious attacks against an indispensable critique of extractivism, carried out by “good” progressives, which were a root cause of the split between the Indigenous movement and Correism, should move us to think beyond the elections. When electoral representation and language are the dominant focus, it is hard to transcend the media wars that prevent substantive discussion of the social model’s functioning at its roots. The rebuilding of the Indigenous movement’s unity and strength in resisting assaults on territories will also need to take place beyond the electoral realm.

[Ed. — This article will be appearing in the Winter 2022 print issue of New Politics.]

[Ed. — This article will be appearing in the Winter 2022 print issue of New Politics.]

This article was written for L’Anticapitaliste, the weekly newspaper of the New Anticapitalist Party (NPA) of France.

This article was written for L’Anticapitaliste, the weekly newspaper of the New Anticapitalist Party (NPA) of France.

Nearly a year to the day before his untimely death, renowned anarchist anthropologist David Graeber wrote

Nearly a year to the day before his untimely death, renowned anarchist anthropologist David Graeber wrote

This article was written for L’Anticapitaliste, the weekly newspaper of the New Anticapitalist Party (NPA) of France.

This article was written for L’Anticapitaliste, the weekly newspaper of the New Anticapitalist Party (NPA) of France. The biggest result of the Great Resignation has been the rise in wages as employers try to entice workers. Wages reached an average of $31 an hour in August, a yearly 4.3% increase and an all-time high. For twenty-five years, employers would not raise wages, but now from McDonald’s to Bank of America they are.

The biggest result of the Great Resignation has been the rise in wages as employers try to entice workers. Wages reached an average of $31 an hour in August, a yearly 4.3% increase and an all-time high. For twenty-five years, employers would not raise wages, but now from McDonald’s to Bank of America they are.

The national day of strikes and demonstrations organized in France on 5 October, called by the unions CGT, FO, FSU and Solidaires, will not go down in history; it was not a failure, but the mobilization was average in terms of demonstrations and weak in terms of strikes. Part of the “trade union left” refers to “the widespread apathy of the trade union leaderships”. Apart from the point of discussion about the notion of “leadership” for a trade union organization, isn’t there a risk of simplifying a more complex situation? Does our problem really come from a supposed apathy of leaders Philippe Martinez, Yves Veyrier, Benoit Teste, Simon Duteil, Murielle Guilbert

The national day of strikes and demonstrations organized in France on 5 October, called by the unions CGT, FO, FSU and Solidaires, will not go down in history; it was not a failure, but the mobilization was average in terms of demonstrations and weak in terms of strikes. Part of the “trade union left” refers to “the widespread apathy of the trade union leaderships”. Apart from the point of discussion about the notion of “leadership” for a trade union organization, isn’t there a risk of simplifying a more complex situation? Does our problem really come from a supposed apathy of leaders Philippe Martinez, Yves Veyrier, Benoit Teste, Simon Duteil, Murielle Guilbert

Editor’s note: A constellation of events has thrown left wing memes into the mainstream, leading to a confirmation of the late Mark Fisher’s thesis that countercultural trends tend to be co-opted by capitalist media. The viral spread of AOCs ‘”Tax the rich” dress and of Grimes’ ostentatious public walkabout reading Marx’s Communist Manifesto have coincided with an explosion of memes featuring the late British theorist, Mark Fisher himself—subjecting one of our era’s most powerful critics of capitalism to the whims of internet algorithms. Eudald Espluga examines these trends in the light of the publication of

Editor’s note: A constellation of events has thrown left wing memes into the mainstream, leading to a confirmation of the late Mark Fisher’s thesis that countercultural trends tend to be co-opted by capitalist media. The viral spread of AOCs ‘”Tax the rich” dress and of Grimes’ ostentatious public walkabout reading Marx’s Communist Manifesto have coincided with an explosion of memes featuring the late British theorist, Mark Fisher himself—subjecting one of our era’s most powerful critics of capitalism to the whims of internet algorithms. Eudald Espluga examines these trends in the light of the publication of

The neoliberal university exploits intellectual labor under a veneer of liberal-humanist values — a false consciousness which the emerging working-class academics must overcome.

The neoliberal university exploits intellectual labor under a veneer of liberal-humanist values — a false consciousness which the emerging working-class academics must overcome.

The rising movement among contingent faculty has pushed bills onto CA Gov. Newsom’s desk and into the budget reconciliation process in Congress. California’s State Assembly Bill 375 would lift “the 67% law, affecting thousands of community college (CC) faculty, 70-75% of the total CC faculty workforce. The “67% law” limits faculty hired in this way to teaching no more than two thirds of a full load. Lifting it would only adjust one pressure point in the work-lives of these faculty, but it would allow the them to consolidate their assignments and perhaps teach at one or two different institutions instead of two, three or more. It’s a tweak, but it would help pay the bills. Not surprisingly, this low-wage tier of workers, mostly without benefits, hired as precarious workers without job security, is disproportionately women and people of color.

The rising movement among contingent faculty has pushed bills onto CA Gov. Newsom’s desk and into the budget reconciliation process in Congress. California’s State Assembly Bill 375 would lift “the 67% law, affecting thousands of community college (CC) faculty, 70-75% of the total CC faculty workforce. The “67% law” limits faculty hired in this way to teaching no more than two thirds of a full load. Lifting it would only adjust one pressure point in the work-lives of these faculty, but it would allow the them to consolidate their assignments and perhaps teach at one or two different institutions instead of two, three or more. It’s a tweak, but it would help pay the bills. Not surprisingly, this low-wage tier of workers, mostly without benefits, hired as precarious workers without job security, is disproportionately women and people of color.

This article was written for L’Anticapitaliste, the weekly newspaper of the New Anticapitalist Party (NPA) of France.

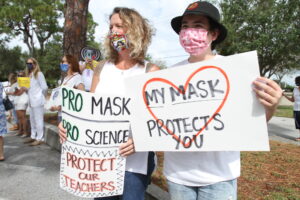

This article was written for L’Anticapitaliste, the weekly newspaper of the New Anticapitalist Party (NPA) of France. Sponsored by over 200 women’s rights and liberal organizations such as Planned Parenthood, the National Organization for Women, and the American Civil Liberties Union, but also mobilizing scores of smaller local groups, in big cities and small towns women of all ages and their male and other gender allies chanted, “My body, my choice.” Demonstrators displayed signs that with wit and sarcasm expressed their frustration. One sign read, “If men got pregnant, abortion would be legal everywhere.” Another said, “Mandatory vasectomies. Come on guys, let’s save lives.” And another mocking biblical language, “He who hath no vagina should just STFU [shut the fuck up].

Sponsored by over 200 women’s rights and liberal organizations such as Planned Parenthood, the National Organization for Women, and the American Civil Liberties Union, but also mobilizing scores of smaller local groups, in big cities and small towns women of all ages and their male and other gender allies chanted, “My body, my choice.” Demonstrators displayed signs that with wit and sarcasm expressed their frustration. One sign read, “If men got pregnant, abortion would be legal everywhere.” Another said, “Mandatory vasectomies. Come on guys, let’s save lives.” And another mocking biblical language, “He who hath no vagina should just STFU [shut the fuck up]. In New York City where my wife and I marched, the rally began with demonstrators chanting, “Black Lives Matter.” Rose Baseil Massa, an organizer for March for Abortion Justice, told the crowd, “We know that Brown and Black people, Hispanic and Latinx populations and indigenous populations, they are all disproportionately affected by abortion bans. So it’s really important for us to stand here in solidarity.” The notion of solidarity with people of color was a central theme, though the protest n New York City, where whites are a minority, was overwhelmingly white, with few Black women present.

In New York City where my wife and I marched, the rally began with demonstrators chanting, “Black Lives Matter.” Rose Baseil Massa, an organizer for March for Abortion Justice, told the crowd, “We know that Brown and Black people, Hispanic and Latinx populations and indigenous populations, they are all disproportionately affected by abortion bans. So it’s really important for us to stand here in solidarity.” The notion of solidarity with people of color was a central theme, though the protest n New York City, where whites are a minority, was overwhelmingly white, with few Black women present. Women made up 70 percent of the participants in New York City, some of them veterans of the women’s movement of the 1960s and 70s, but mostly younger women, some new to the movement. The politics of the march in NYC were progressive, with a strong presence of Democratic organizations, such as Indivisible and several independent Democratic clubs. Some women carried signs such as, “RBG sent me,” a reference to the recently deceased liberal Supreme Court justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg. There were a couple of leftist organizations present, Maoist and Trotskyist, but they represented a tiny minority. The Democratic Socialists of America, the country’s largest group, had no visible presence here.

Women made up 70 percent of the participants in New York City, some of them veterans of the women’s movement of the 1960s and 70s, but mostly younger women, some new to the movement. The politics of the march in NYC were progressive, with a strong presence of Democratic organizations, such as Indivisible and several independent Democratic clubs. Some women carried signs such as, “RBG sent me,” a reference to the recently deceased liberal Supreme Court justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg. There were a couple of leftist organizations present, Maoist and Trotskyist, but they represented a tiny minority. The Democratic Socialists of America, the country’s largest group, had no visible presence here. In Asheville, North Carolina Tessa Paul, local DSA co-chair, told a rally, “We are gathered here today because there is a war being waged. This is a war against women’s reproductive rights, against trans and nonbinary people, against Black and Brown people, against indigenous, queer, disabled, displaced and abused people.” There is a war, but women have begun to fight back and we stand with them.

In Asheville, North Carolina Tessa Paul, local DSA co-chair, told a rally, “We are gathered here today because there is a war being waged. This is a war against women’s reproductive rights, against trans and nonbinary people, against Black and Brown people, against indigenous, queer, disabled, displaced and abused people.” There is a war, but women have begun to fight back and we stand with them.