Ani White: Kia ora, hello comrades. Welcome to Where’s My Jetpack?!, a politics and pop culture podcast with sci-fi and socialist leanings. I’m Ani White and today we’re interviewing trade unionist, socialist and migrants’ rights advocate Gayaal Iddamalgoda. Earlier [in 2020] we interviewed Gayaal on migrant and refugee rights in the age of Covid and now we’re talking about the Tankie revival and how rubbish it is.

Welcome to the show.

Gayaal Iddamalgoda: Kia ora, thank you Ani.

Ani White: Good to have you. So, to start off a bit of historical context. Ten years ago you could argue Stalinists were irrelevant in the West.

Gayaal Iddamalgoda: Yes, absolutely. At the time I was in a third-camp International Socialist Organisation and you were in the multi-tendency Workers’ Party, and the leadership of my organisation, the ISO, took great delight in accusing the Workers’ Party and pretty much any radical socialist organisation of being Stalinists and it was very polemical. It was pretty much a mainstay of my experience of radical politics at least in the early times, and at the time of course it didn’t have much substance to it, and it was pretty much just a polemical device to denounce supposedly rival organisations.

Ani White: Yeah, we sort of had this Maoist lineage but honestly we were probably a lot more Trotskyist. But the two of us, along with a lot of the younger comrades of both organisations, we developed a stronger relationship in spite of the leadership of both organisations. You had this interesting generational split where the leadership were very polemical about each other but the younger comrades developed more of a relationship. At the time I argued Stalinism was irrelevant in the 21st century and that was a pretty common perspective in the Workers’ Party at the time, that Stalinism just wasn’t worth opposing. You know, it was bad but it didn’t really matter that much. But whether or not we were right at the time and I’m not sure about that, whether or not we were right at the time that has changed with this kind of strange neo-Tankie revival through the internet. So, there are a lot more Stalinists around in the movement now than there were about ten years ago. It used to be kind of Joe down the road and his one person Communist Party. That would be the Stalinists, whereas now there’s a lot more young people who actually believe in it. So I kind of joke that this is not the socialist revival we wanted but the socialist revival we deserved.

The new features of this Stalinist revival are – meme culture and a mingling with strange forms of identity politics, where people argue the only way to be anti-racist is to support states like Iran or what have you. In some ways this revival doesn’t sit well with the history of Stalinism which has been pretty gender normative and, as we’re going to argue, pretty racist. I know this is something the right likes to say but, honestly, a lot of Stalinists wouldn’t feel well in a Stalinist space. Neo-Tankism is just dismissed as just an internet phenomenon and it’s true, there are no mass Stalinist parties in the West, particularly in the Anglosphere. But then the Alt-right were previously just an internet phenomenon as well and internet politics are a part of real world politics and digital media have become the main context for communication. The concept of a Tankie, it’s not actually new, it’s seen as an internet meme but it actually goes back to the crushing of the Hungary and Prague democracy movements by literal Russian tanks. The term Tankie can be found in Communist Party of Great Britain, C.P.G.B., documents from decades ago so it’s not so much new as it’s been revived along with other zombies of the 20th century.

Tankie, just to define it, refers broadly to supporting so-called actually existing socialist states such as China and also so-called anti-imperialist states like Iran. It’s a kind of degeneration of socialist politics that prioritises solidarity with states over solidarity with people. And the central claim of Tankie politics is it’s the best way of defending socialism in the face of imperialism. It’s probably the most coherent theory or defence they have. In practice that empties out all of the radical content of socialism. So, as seen at the inception of Stalinist politics in the 1930s when Stalin purged, executed or exiled most remaining members of the 1917 Central Committee. So it sort of defends and wins while emptying out all of the radical content of socialism.

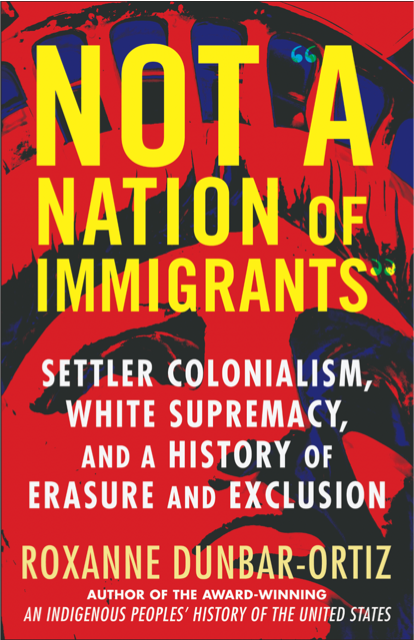

We’re going to be talking more about one of the central claims of contemporary Tankism, which is that it’s the politics of the third world, unlike anarchy or Trotskyism. We argue that’s actually erasing struggles of the majority world. So to go into one example Gayaal’s going to talk about the history of Trotskyism in Sri Lanka.

Gayaal Iddamalgoda: Yes. You made a very good point Ani. Many Tankies, many socialists, wouldn’t fare well in the so-called actually existing states or the anti-imperialist states that they support. And what I hope to convey through giving a very brief overview of the Lanka Sama Samaja Party, which is the first Trotskyist organisation in Sri Lanka – in fact it was the first political party in Sri Lanka – is that when you say things like that you’re implicitly accepting that people of colour, people who are not in the Anglosphere, their version of liberation or their version of human dignity or their version of workers’ struggle should be limited, should be abridged and essentially they should – and this is of course not explicitly stated – but essentially they should accept brutal regimes. They should accept torture. They should accept curtailment of their liberties and freedoms. And they should accept inequality because the best that they can hope for is a supposedly anti-imperialist regime to rule over them. I think hopefully at the end of this show people will be able to consider why that is obviously racist and why, as you said, it actually erases the vibrant struggle of people in the third world, or working class people in the third world I should say more explicitly, because they are every bit as capable of contesting their political, social and economic rights as working class people anywhere else in the world. They should not have to settle for any less than what people would expect in the Anglosphere.

Just getting into this history of Trotskyism in Sri Lanka – first of all I should say that it’s quite a personally significant history for me. because members of my family have been very conspicuous supporters of the Lanka Sama Samaja Party, or the Trotskyist party that was instrumental in the struggle for independence against Imperialist Britain in Sri Lanka. In fact I think I may have told you this Ani. but one of my relatives was a member of the Lanka Sama Samaja Party, very prominent, and some reactionaries took revenge upon the family by plastering my great grandparents’ tombs, or I should say tarring, my great grandparents tombs with the symbol of the hammer and sickle. So that tar has been chipped off but if you visit my great grandparents tombs even today you will see the outline of a hammer and sickle, and that is in my mind forever a testament to politically something to be proud of in my family history. With that personal anecdote I’ll get into some of the actual details of the Trotskyist movement in Sri Lanka.

As I said, Trotskyism in Sri Lanka started in the ’30s and in the ’40s and it had its formation during the anti-imperialist struggle of the Sri Lankan working class and the attempts of the Sri Lankan working class to rid themselves of colonial Britain. If you know anything about Sri Lankan politics today, what should stick out to anyone who studies the Lanka Sama Samaja Party, is the complete rejection, at least in the early days, of communal and ethnic chauvinism. This was an organisation of workers that was committed to uniting Tamil, Sinhalese and migrant Tamil workers in the struggle against imperialism. They really earned their stripes from the early ’30s onwards when they were organising the Lanka tea estate workers – the name of the union was the Lanka Estate Workers’ Union – in a series of mass strikes in the ’30s and ’40s that were designed to break the back of the colonial economy. The interesting thing about the workers in those tea plantations was they were overwhelmingly migrant origin Tamil workers, and the struggles that the Lanka Sama Samaja Party was leading them to were working class struggles that prioritised the interests of working class people, regardless of whether they were Sinhalese or Tamil. There was a famous strike in 1933, one of the first strikes that they organised. One of the largest spinning mills in Sri Lanka at the time, so mostly women, two-thirds of the workers, 1,500 workers, two-thirds of them were Tamils, one-third of them were Sinhalese. The Lanka Sama Samaja Party lead an extremely high-profile and successful strike, one of the earliest strikes. So this ethnic solidarity has always been a hallmark of genuine workers struggle in Sri Lanka.

Another hallmark of the struggle lead by the Lanka Sama Samaja Party was staunch anti-imperialism. The 1930s and 1940s was actually a time when many communist parties around the world were telling workers to prioritise the Allied struggle against Germany and the Axis Powers and to put aside the more immediate issues with the capitalist, imperialist regimes that they lived under. But the Sri Lankan Trotskyists made a very clear stance that they would not prioritise the interests of Britain over the interests of Sri Lankan workers, and as far as they were concerned Sri Lanka was an occupied state, was an occupied nation. The Sinhalese and Tamil workers were in no way going to put their struggle for independence on hold while Britain pursued its war. This was a very radical and very staunch anti-imperialist stance that they took. They of course stood very firmly against fascism but they were also very particular to say that the Sri Lankan workers were an oppressed people and they could not be called upon to shed blood for the benefit of their imperialist overlords.

So because of this Sri Lanka has a very interesting history during World War II. Sri Lanka was, I understand, the only part of the commonwealth where rationing wasn’t vigorously imposed, because the agitation of the Lanka Sama Samaja Party was such that the British imperialists were afraid to do anything to upset the Sri Lankan populous; the Sri Lankan working class. A beautiful illustration of the power that these Trotskyists were able to harness in the working class in Sri Lanka: the only troop mutiny on the Allied side during World War II were a group of Sri Lankan workers who were deployed – not workers, I should say soldiers. There was very little, there was no conscription during World War II and there was a small contingent of Sri Lankan soldiers sent to the Cocos Islands in Australia, and they mutinied and attempted to dubiously hand over the island to Japanese Imperialist powers. But it was certainly those soldiers who cited the Lanka Sama Samaja Party as the reason for their refusal to cooperate with the imperialist agendas. So I think that’s another hallmark of the Lanka Sama Samaja Party.

After the 1947 general election, so after Sri Lanka attained independence there was a general election, and the Lanka Sama Samaja Party was in fact the main opposition party and this was a tremendous political gain for the Sri Lankan working class, both Sinhalese and Tamil. Now the thing about Sri Lanka, as you might know, the British when they left the country they made sure that as much power remained in the hands of Anglicised Sinhalese and Tamil elites. These elites were desperately trying to appeal to ethnic Sinhalese elites, in particular desperately trying to appeal to ethnic chauvinism in order to relate to the people they were ruling. Like, ‘we’re wealthy and we run everything but at least we’re Sinhalese’ essentially. The tried and true strategy of using racism to divide the working class. But the Lanka Sama Samaja Party was a powerful and effective counter to that and in the ’50s and ’60s they continued with wave after wave of strike. Again very, very successfully organising Tamil workers and Sinhalese workers together. I think that’s essentially what the reactionary forces in Sri Lankan politics started to target; was this unity. Their game was to sow ethnic hatred and one of the main things they did was they passed the act of constitution in 1948. This ostensibly was to establish a constitution of an independent Sri Lanka, or Ceylon as it was called then. But the effect of it was to disenfranchise thousands and thousands of Tamil workers who had lived in Sri Lanka for generations, and who worked on those plantations that the Lanka Sama Samaja Party organised. It was an attempt to break the back of the working class struggle, or the most radical section of the working class, that was based on these colonial plantations. The other thing that happened was in 1956 the Sinhalese chauvinists in power, they passed the Sinhala Only Act which made Sinhalese the only official language in Sri Lanka and essentially targeted, at that time, 30% of the population that spoke Tamil and marginalised them. It was very much calculated to destroy that unity of the working class that the Lanka Sama Samaja Party was able to command. In fact they came out staunchly and strongly in opposition to that. There was a famous speech given by a Sri Lankan Trotskyist, [Colvin R. de Silva] – it’s quite a long speech, so I won’t read out the whole thing – but he said:

“Do we want one Ceylon or do we want two? And above all, do we want an independent Ceylon which must necessarily be united and single and single Ceylon, or two bleeding halves of Ceylon which can be gobbled up by every ravaging imperialist monster that may happen to range the Indian ocean?”

So, in no uncertain terms this organisation was able to call out communal politics and say that it was detrimental to the working class. I think this is the thing Tankies should understand – Brown people, people in the third world, they are able to figure out what’s best for them. Their political traditions are rich, they’re vibrant, their traditions of struggle are rich and vibrant, they are contested spaces, right? So I think it’s a huge mistake to look at them and say, ‘no, all that they’re fit for is repression, ethnic chauvinism and perhaps, say, a broadly anti-imperialist state to rule over them.’ I think that’s, at the very least, extremely very narrow minded. I think the Sri Lankan Trotskyists are an object lesson of how Stalinism and statism isn’t the organic choice of the working class in the third world. It doesn’t have to be. It isn’t. And, of course, these other traditions have been stifled, have been attacked and stifled. I think genuine solidarity with workers in the third world would mean that we should reach out to those other traditions, understand those traditions and understand the nuances instead of making assumptions about what’s good for workers in the third world.

For someone from my generation of Sri Lankan people, the idea that there was a time when that kind of solidarity between Sinhalese and Tamil workers existed just seems so foreign, so alien and so distant. But it did exist and it was destroyed by reactionary intervention. I think that’s something that is a real testament to the achievement of the Trotskyists in Sri Lanka and even today because of their struggle against British imperialism, Sri Lanka is officially called the Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka. That’s what it’s called on paper. Obviously it’s not a democratic socialist republic but because of the tremendous hand that Trotskyists had in founding independent Sri Lanka that’s what it’s called. Until this day Sri Lanka has free education all the way up to university, it has free healthcare, it has one of the highest literacy rates in the world. Because it was supposedly founded on democratic socialist values. That is owed to the Sri Lankan Trotskyists and something that Sri Lankan Trotskyists should be very proud of.

Ani White: Thanks for that Gayaal, that was very informative and interesting. I mean, I have read bits and pieces but that laid it out and covered a lot of stuff that I wasn’t aware of. I understand they made an electoral alliance that didn’t work out. Do you have any comments on that?

Gayaal Iddamalgoda: This is in the ’70s. They made an electoral alliance, I believe, with the S.L.F.P. (Sri Lanka Freedom Party) which had very strong reactionary elements. And also in the ’70s they had a lot of splits within the Trotskyist communist movement. Many of them became associated with Moscow and with Stalinism, right? And I think those splits were really detrimental. But of course, that’s not organic, that was an intervention from the outside. It wasn’t an organic development within the class politics of Sri Lanka. In the 1970s as a result of those splits, I would say, and also as a result of them trying to find an accommodation with some of these chauvinist bourgeois parties, they lost all their seats. So in the general election which I think was in 1974, they essentially lost all of their seats, and ever since they haven’t been able to regain because the communalist politics of the bourgeoisie gained greater and greater ascendancy.

Ani White: Yeah, and the ’70s was a pretty bad time for a lot of the left internationally. Also, I’ve had some interest in Fourth International which backed that party and part of their account is about the collapse of that alliance. But certainly, Stalinist parties made those sort of alliances very early on, like right from the ’30s. I mean, we can probably grant that Sri Lanka was a relatively unusual case in terms of the scale of the Trotskyist movement. In a lot of cases, either in the West or in the majority world, Stalinist parties were the largest, and the Trotskyist parties began as a breakaway from that. So it’s hard to re-establish the same kind of mass base that Stalinists had at that time which they ultimately squandered. But even if we acknowledge that Stalinist parties have generally been the largest historically, that certainly doesn’t mean they’re the only radical currents in the majority world and making that claim, as we’ve said, it homogenises majority world struggle. The way that it’s kind of “one socialism for us, the core countries, and another socialism for people in the majority world”, that forms of oppression we wouldn’t accept here ‘we’ can accept there. When I say ‘we’ I am referring to Tankies.

Another reason Trotskyists and anarchists couldn’t get a foothold is that Stalinists outright massacred them in a lot of cases. So it can be hard-

Gayaal Iddamalgoda: Absolutely. Like in Vietnam, for example.

Ani White: Yeah, yeah, absolutely. Also in parts of Latin America; Peru, and all of that.

Gayaal Iddamalgoda: Mmm.

Ani White: Another country whose radical history is erased by these kind of Stalinist claims is the Philippines, where really the international voice of the left for the Philippines is generally the Communist Party. Even though that’s far from the only current of radical, progressive, or socialist politics in the Philippines – and it’s certainly true that the Communist Party of the Philippines, the C.P.P., has had a significant impact on Filipino radical history – but to claim that Maoism is the radical current of the Philippines, sort of the only radical current, and that other currents are just Trotskyism or are just a foreign imposition, they actually erase the work of many Philippino activists and organisers. As I’m going to talk about, I paid a visit to the Philippines for a socialist seminar where I learnt about some amazing work that people were doing who were from a breakaway group from the C.P.P.. The C.P.P. has, as I said, a near-monopoly on recent accounts, Western Communist accounts of the Philippines, even though there are other groups which have broken with it, or challenged it, or were never aligned with it who are rarely acknowledged in English-language accounts.

This gets particularly problematic when you have something like the C.P.P. endorsing a fascist like Duterte and having their international mouthpieces echo that and then six months later claim it never happened. So, for a concrete account of the C.P.P.’s relationship with Duterte I’d recommend the work of Joseph Scalice. We’ll link a YouTube lecture by him in the description. One thing I’ve found is it’s pretty much gaslighting. So people will claim that they never supported Duterte, that it’s slander, and you can go back and find explicitly they’re campaigning for Duterte to be elected. They’re at rallies alongside him but now there reaches a point of denial where you do genuinely wonder if you’re crazy or you’re exaggerating. And the useful thing about Scalice’s work is he actually documents the atlliance. So it’s like, ‘oh yeah that did actually happen, they were actually supporting Duterte.’

One of the reasons that the anti-imperialists initially supported Duterte was because he made gestures towards opposing the U.S. Military, which don’t seem to have really followed through. But opposing the U.S. doesn’t have to mean supporting terrible figures like Duterte or Putin, Xi Jinping or Assad and there’s another aspect to it which I can understand, which is that the C.P.P. was in peace negotiations with Duterte. But, you know, you don’t actually have to campaign for the person you’re in peace negotiations with – that’s not really how that works. It was a decision they made to support him that goes beyond being in peace negotiations. There’s a lot of peace negotiations where the two sides will certainly not endorse the other side. But often when you point out the counter-revolutionary violence of these various strongman figures – so less so Duterte now because it’s been acknowledged that he’s terrible – but say with Xi Jinping or Assad, people respond that the U.S. does bad things. To which we kind of respond, ‘well, yeah, obviously the U.S. does bad things, U.S. imperialism is bad.’ So we have protested outside the Russian embassy, for example, and been asked ‘why aren’t you protesting outside the U.S. embassy’ and we have. So you can oppose the U.S. and also oppose Duterte when he makes moves towards challenging them and I think that’s a situation of whoever wins, we lose. So rather than supporting geopolitical camps, we support democracy movements regardless of what side of geopolitical line they’re on.

So getting back to the Philippines – that was a bit of a tangent – but in June 2019 I visited the Philippines for the Asia Pacific Regional Seminar of the International Institute for Research in Education, or IIRE, an organisation which is broadly affiliated with the [Fourth] International and the Revolutionary Worker’s Party of Mindanao, RPM-M. As I’ve mentioned on the podcast before, this seminar was easily the most stimulating socialist educational event I’ve ever attended, and I’ve attended quite a lot. With comrades from Fourth International sections or semi-affiliated organisations, because some are directly in the Fourth International and some are sort of at arms length. But with comrades from every continent but Antarctica really. So you had comrades from Brazil, from Pakistan, from Japan and sharing those experiences and ideas was very stimulating and the style of education was genuinely participatory. So, for example, you could have people discussing the different situations for gender and sexuality struggles in different countries where, for example, in the Philippines, and this does actually include the Communist Party but also other sections of the left have been pretty good in terms of LGBT struggles, so they were conducting gay marriages before the state was. Whereas Pakistan, there were comrades there who were saying, ‘we want to support these struggles but we don’t really know about them’.

Comrades in the Philippines seminar did emphasise generally in my experience, that for the RPM-M, the political is primary over the military struggle, whereas for the CPP, the military is primary over the political. So for the CPP it’s primarily a guerilla war and that is how they conceive of their strategy. Whereas for the Mindanao section, primary is the struggle around issues like peasants’ rights, workers’ rights, LGBT rights and their military section is only used for self-defence. So it’s only used to defend its section and not as their sort of primary, strategic orientation.

For the remainder I’m going to quote another piece in-full, outlining the history of the RPM-M and as usual you can find a link to the full article in the description:

“A country plundered of its natural resources, its tropical forests decimated: simmering armed conflicts: a corrupt state, carrying a debt of billions, incapable and unwilling to ease the daily suffering and hunger of its citizens: millions forced to work abroad…The Philippines is a textbook example of the effects of neoliberal globalization.

For years the Revolutionary Workers Party of Mindanao (RPM-M) and its predecessors have been trying to organise the poor and oppressed of Mindanao, the large island in the south of the Philippines archipelago, to struggle for change. The party, since 2003 a section of the Fourth International, has its roots in the Maoist Communist Party of the Philippines (CPP).

In the 1970s and 1980s the CPP and its allies in the National-Democratic movement had complete hegemony over the left in the Philippines. The fall of the corrupt regime of Ferdinand Marcos in 1986, however, turned out to be a defeat in victory for the CPP. The organisation that had made such great sacrifices to wear down the dictatorship found itself isolated from the mass movement because of its insistence on the primary role of armed struggle in the countryside and the boycott of elections.”

Ani White: Which by the way – a side note – [the CPP have] since reversed that position; they do participate in elections now without at any point saying they were wrong. So they purged people for advocating for a position and then have since adopted that perspective which is very typical Stalinist party stuff.

But returning to the article:

“Members of the CCP or “the old party”, as it is referred to by former members, still cling to the interpretation of Maoism it started out with in the 1960s. For them the current regime of president…”

Ani White: …okay, this is the previous president…

“…[Gloria Macapagal] Arroyo is not really different from that of Marcos. They see the country as still “semi-feudal and semi-colonial”.

Certainly the official democracy is a sham. Since 2001 more than 1,000 social justice and human rights activists have been murdered or “disappeared”. Nobody has been convicted for these crimes, even though it is an open secret that the murderers and torturers are to be found in the military, the police and the many private armies.

At least after the monopoly on power by Marcos and his cronies competition between factions of the ruling elite has opened up some political space, something the National-Democrats also implicitly admit by participating in the elections with their own electoral formations. Since the fall of Marcos, the Philippines has become more and more integrated into the global economy. Big landlords are still powerful but the export of raw materials and cheap labour have become more important and the role of capital in agriculture has increased. A growing part of the population lives in the cities.

The RPM-M and its predecessors had been in contact with the Fourth International since the 1990s, trying to orient themselves in the new situation. Harry Tubongbanwa, once a CPP leader in Mindanao and now a leading RPM-M activist, explains: ‘We consider our struggle to be a fight against imperialism that must be part of an international struggle of progressive and socialist organisations’. His party sees a need to fight for basic democratic fights and now gives more attention to legal mass campaigns…

For the RPM-M democracy and self-determination are integral parts of the struggle for revolutionary change. Mass movements are the key: arms are necessary to protect movements and activists but do not guarantee victory.

Members of the party’s armed wing, the Revolutionary Peoples’ Army, secure party gatherings in the mountains of Mindanao and protect villages sympathetic to the party from criminals and private armies. Other tasks involve training self-defence groups of indigenous people that resist the destruction of their native lands by mining companies, and also helping peasants with harvesting and planting.

In 2005 the RPM-M negotiated a ceasefire with the national government. In return the party demanded that the government install running water and electricity for dozens of isolated, impoverished villages in Mindanao. …

Tragically, the most recent clashes involving RPA fighters were with the New People’s Army of the CPP. The CPP has denounced every left group that does not follow the National-Democratic framework as traitors and counter-revolutionaries. Numerous left-wing activists, including several RPM-M members, have been murdered by the Maoists. …

Mindanao is a troubled part of the country. Since the 1970s, the national army has been fighting the CPP and also separatist Islamic movements, a conflict that sometimes became a full-scale civil war. Anti-war campaigning and relief work for the war-victims are priorities in for socialists in Mindanao. Their work shows a very practical interpretation of anti-imperialism and the struggle against poverty, and foreign and Filipino capital.

The RPM-M is now a growing organisation of some 2,500 members and for the first time is expanding its work beyond Mindanao, all the time undergoing deep changes. For example women’s liberation is an integral element in all the work and the party has organised a lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender group.”

Ani White: So, if you want to learn more about the Philippines section of the Fourth International we’ll link their English language website in the description. But again, groups like the RPM-M are erased when people claim that Maoism is the radical politics of the third world or that other currents are non-existent or somehow imposed. The irony is that the Fourth International is often treated as a joke because its Western sections are small, but their more significant sections in the majority world have been forgotten and ignored.

Gayaal Iddamalgoda: It’s really interesting, Ani, some of the things that you mentioned in your spiel about the Philippines. I think the issue with Tankism and with Stalinism is a rejection of genuine internationalism. and I think replacing genuine internationalism or international workers’ struggle with this dogmatic idea that every society or every country has a form of socialism that’s tailor-made for it or a form of anti-imperialism that’s tailor-made for it, for its organic qualities of the people who live there, which is all completely reductionist and essentialist nonsense. The way this plays out can be quite dangerous, that’s the thing. When you do see movements or people in the majority world contesting their rights and claiming that they don’t want to live under any form of oppression, functioning as the revolutionary class that they are, many Tankies, because of their dogmatic position about anti-imperialism or statism, they’ll actually aggressively oppose those movements. They will not see them for what they are; which is the natural resistance of the mass of the working class.

I think in Wellington we have had some issues with some Tankies or one Tankie in particular who was very, very pro-China and believed that that was the genuinely socialist position. In New Zealand this person would obviously support all sorts of progressive politics positions; on gender equality, on queer activism, all that kind of thing. But when it came to activists in China contesting a regime that denies them these things, they immediately took the side of the repressive regime because dogmatically China is an anti-imperialist so-called “existing socialist state”. This person, during the Hong Kong protests, actually surveilled, took pictures of, Hong Kong protesters, students from Hong Kong who are protesting in New Zealand and actually, presumably handed them over to the Chinese embassy here. This is not only completely misguided, it is actually dangerous. You have someone here who is so committed to this position that China is an actually-existing socialist state and that has to be protected at all costs, even from its own working class, that they’re actually willing to expose the families of these students who are protesting to danger.

Ani White: I saw people respond to this person as a LARPer and that was their response to this whole situation, and say that we shouldn’t care about it, which I think was pretty appalling. Because whether or not they were actually acting as a cop – in other words, whether or not they actually handed those pictures over – it was obviously an intimidation tactic and, as you say, playing on people’s fears of things happening to their family or being deported or what have you. This is behaving as a cop, essentially, so that’s the point where Tankism goes from LARPing into being a cop, really.

Gayaal Iddamalgoda: It’s not LARPing at all. If only it was that innocuous. It’s extremely dangerous and completely disconnected from a genuine perspective on class struggle. I think you mentioned also in what you were saying earlier about Assadism. Again I see a lot of parallels between what people say about Sri Lanka and the kind of society that Sri Lanka is; mired in ethnic conflict and in need of the strong man to keep all of these crazy people in the hot place together – people on the left say that about Assad. They say, ‘well, yes, there is sectarianism and yes, he does stoke some of the worst elements of sectarianism in society but you know, he’s all they have. That’s all that we have to principally support him at all costs.’ That is complete rubbish and is frankly insulting to the Syrian people who have expressed their desire for freedom in very unequivocal ways. They want to live in a society that is not a dictatorship. They want to live in a democracy where everyone is equal. These currents exist, but Tankies are incapable of actually recognising these currents for what they are because of their dogmatic stance. I think, also, this has always been a problem with Stalinism. As you said, the origin of the word Tankie – people who supported the crushing of pro-democracy activism in Hungary with tanks were call Tankies. Well nowadays you have Tankies doing such absurd, abhorrent things as denying the genocide and the ethnic cleansing of the Uighurs in East Turkmenistan by the Chinese state. This is surely in our generation one of the most tragic and despicable positions that the radical left could take. Ignoring the call for Uighur self-determination and actually completely denying what is actually happening to this group in China. We’re not going to be taken seriously on the radical left if this is the kind of thing that is expressed. I think the radical left has a strong duty to call it out and to actually acknowledge the oppression that’s going on and show solidarity with oppressed people everywhere.

Ani White: Yeah, with the Uighur struggle as well as outright denial, you also see arguments that would not be accepted when it comes to oppression in the West. So you see people saying, ‘this is radical Islamic terrorists’, and that makes it okay to police an entire community. Certainly for these people and correctly, it would not be accepted if it was the Australian or the U.S. state saying that, ‘well, because there are radical Muslims therefore criminalising an entire community is acceptable’. I like to say: ‘Fascists are consistently reactionary. Tankies are inconsistently reactionary’. They’re reactionary on some questions; usually when it comes to the third world or anything seen to oppose the U.S. and are not so reactionary when it comes to their own struggles essentially.

Tankies oppose prisons in the West but support them in China. They accuse people of being cops when they act like cops. They accuse people of racism while erasing the struggles of actual people of colour and one of the claims of Tankies is that criticism of the Chinese state is Orientalist or Sinophobic. Granted, there is a history of Sinophobia and Yellow Peril discourse in Australasia and elsewhere. We’ve recently seen this bizarre war between Australia and China, where my take on it is ‘whoever wins, we lose’. But the solution is a class line – so it’s not romanticising the Chinese state as a way of countering Sinophobia. So, in the case of China we back Chinese workers, not the Chinese state or capital – just as we would anywhere. So, tens of thousands of Chinese workers have gone on strike in recent years. According to China Labour Bulletin strikes increased 13 fold over five years – so that’s where our sympathy lies. It’s not Orientalist to support the same struggles internationally as we would support here.

Recently we’ve seen drum-beating from the Australia and U.S. governments against China. Neither side supports democracy or self-determination. So another way to put this is, neither Washington nor Beijing but international socialism.

I’m sure this line of criticism, as we’ve found often in New Zealand and you see it on social media, it’ll upset not just Tankies but those who are obsessed with left unity and say, ‘we disagree with the Tankies but you can’t criticise them’. But unity needs a principled basis, it needs a common goal and I’m not sure I share a common goal with those who support capital and state against workers. So with this critique in mind, what is to be done?

Gayaal Iddamalgoda: I’ll put it this way. It’s not Sinophobic to support workers in China who are joining trade unions or workers in China who are taking to the streets to demand the rights and freedoms that workers in Australia and New Zealand have and have fought for. That is not Sinophobia. It’s Sinophobic to say that these people need to accept anything less, because they live in China or because they’re of Chinese origin. That’s the issue, that’s where the racism lies. As you said very eloquently, we would not tolerate the kind of repression that the Chinese government metes out to people living in China if it were meted out against the working class in Australia or New Zealand or the U.K. or America. I think that’s the simple point and if you realise that, we can begin to built solidarity with genuine workers’ movements around the world. This is based on internationalism; the understanding that the workers’ struggle is an international struggle. It is a struggle of solidarity between workers in every state and every country. On that basis, every socialist on a principled political basis should support democracy movements everywhere, should support anti-racism everywhere and should celebrate it, and support and reach out to workers self-organisations, instead of fetishising states and leaders.

I think if you actually look at the history of class struggle in the third world without taking a reductionist and essentialist view – which is Orientalist, right? That is the Orientalist thing to do – if you actually look at them you will see that they are capable, they are more than capable of producing their own organic struggles and of pursuing their rights fully as working class people. Organic leaders may emerge from time to time, but as is always the case, leaders should be accountable to the class that elevates them. They should be accountable to the working class and the movement of the working class is what must always come first. This is true anywhere, this is true in the West, this is true in Russia, this is true in Australia, it’s true in New Zealand, it’s true in China, it’s true in Sri Lanka. And I think if anyone wants to delve into this a bit more; it’s fascinating. The history of the majority world struggles is truly fascinating. I’ve spoken a little bit about Sri Lanka, but on Sri Lanka alone there’s huge amounts of information out there about the Sri Lankan Trotskyists and Sri Lankan socialism in general. I would encourage anyone to do their own study into it. I promise you you won’t find it boring at all.

Ani White: A key recent example of this struggle for self-determination is the transnational uprising of 2011 across the Middle East and North Africa, and even inspiring the Occupy movement in the imperialist core, as well as obviously Indignados in Spain. The legacy of 2011 is a living legacy and it will keep reverberating the way 1917 or 1968 do. And again. the fight for democracy is fundamental and it’s an inspiring moment when it breaks out after decades of repression and passivity. Yet Tankies choose what struggles they’ll support based on geo-political camps, on what’s supposedly bad for the U.S. and good for Russia or China, rather than paying attention to struggles on the ground. So one way I put it is – solidarity with people, not with states. The Syrian revolution is a key example of this sort of betrayal. The Communist Party in Syria supported the dictator Assad, against the popular uprising and Tankies internationally have echoed that perspective. This was really a struggle for democracy and if you look into material on the outbreak of 2011, it was non-sectarian, it was democratic, it crossed different communities. Unfortunately, since then it’s kind of been polarised where it’s seen as a Sunni struggle and not as an Alawi struggle or a struggle of minorities or Christians or Shiites. But if you look at 2011 they had slogans like, ‘Sunis and Alawis are one’ and ‘Syria is One’. It was an anti-sectarian and democratic uprising, and one of the real victories of the Assad regime has been to essentially turn it into a sectarian struggle. So they released Salafists from prison at the same time as they were imprisoning democracy activists, for example. The fact that it’s now perceived as a struggle between Assad and ISIS, when ISIS only entered the struggle a few years later in 2014, as really an occupying force coming from Iraq, the fact that it’s now seen as a struggle between Assad and ISIS, I think in itself is a real victory for Assad. That the democratic nature of the 2011 uprising has been completely forgotten and erased, and I really think we need to bring up that history and remind people of it.

One claim we hear whenever that perspective is advanced – really whenever a non-Tankie perspective is advanced on these Christians – is that international politics shouldn’t matter for us in places like New Zealand. But this is messed up on many levels. In the case of the Syrian struggle, the Syrian diaspora is everywhere, it’s the largest refugee community in a generation, at least. So it affects everyone. The idea that we would say that the struggles of the largest refugee community in the world don’t really matter, because if we talk about them we might divide the left, I just think really shows poor priorities. We have Russian embassies on the soil of most countries, just like we have U.S. embassies. International politics are interconnected. There’s a claim some people make that ‘the left doesn’t matter so it has no international influence’. For one thing, that doesn’t mean we can’t show practical solidarity. For example, there’s a radio channel, Radio Fresh in Idlib. It’s a revolutionary radio station, it opposes the Assad regime, but they’ve also been attacked by some of the Islamists for having women as hosts. So they’re a principled democratic group and there was a fund raising campaign for that. You wouldn’t get support for that from a lot of the left groups because of the position on Syria. The point is, even when we’re small we can show practical solidarity with something like that, where you can donate or you can promote it. If we ever aim to be relevant, if we’re not aiming to just be a small milieu of students or what have you, then we’re kind of going to have to work these questions out. You have people who talk of developing a mass socialist party without taking any positions on international questions. which is kind of a nonsense. Ultimately this anti-internationalism, the line that ‘international questions don’t matter and don’t need to be debated’, it’s an unprincipled talking point masking either terrible politics, or fetish for unity for the sake of unity rather than unity for a common goal. And as we’ve said, it’s also just denying and erasing actual struggles in the majority world.

We can learn a lot from these recent, living revolutions. You see it once you delve into the history, that’s absolutely true but even just delving into what’s easily available on struggles in the last few years can be fascinating and you see a lot of leftists doing that, not learning about something like Syria. So we don’t just learn from Russia in 1917, we can learn from Syria 2011. Sure, not all of the lessons from the Syrian Revolution are positive. For example, we have to reckon with the sectarian hijacking, but that’s equally true of Russia 1917 or any other real revolution – there are positive lessons and negative lessons of any revolution. There are tensions and contradictions in any revolution. But in my view if you are a radical, progressive, leftist, whatever you want to call yourself, socialist, you should be reading the work of Syrian revolutionaries in particular in this context, because I think that’s some really important work.

So in that vein I’m just going to suggest a short reading list, so three essential texts on the Syrian revolution because obviously I barely scratched the surface and there’s really a lot that people should know about that struggle. There’s a book called Burning County: Syrians in Revolution and War by Leila Al-Shami and Robin Yassin-Kassab. This book is based on extensive interviews with Syrian revolutionaries and it offers a sort of useful, on-the-ground narrative of the various stages of the conflict.

Another one, The Impossible Revolution: Making Sense of the Syrian Tragedy, which is by Yassin Al-Haj Saleh. Whereas Burning Country operates at the ground-level with these interviews, The Impossible Revolution offers more of a macro level analysis. It’s a collection of essays by Yassin Al-Haj Saleh, starting in 2011 during the revolution and with essays through to 2014. Saleh is an intellectual who was imprisoned by the Assad regime for ten years, for his membership in a Communist Party breakaway which emphasised the struggle for democracy. Nowadays he’s known as the conscience of the revolution. These essays go into depth on the class character of Syrian society; they have a kind of breakdown of the classes in Syrian society, which is honestly much more perceptive than a lot of left writing I’ve read in some time, in terms of actually concretely trying to understand how class works in a given society. It talks about the basis of the revolution; so one of his arguments is that two of the key elements were the dispossessed Sunni majority but also the urban intellectuals. But he goes into various aspects of this. He also goes into the degeneration into sectarianism. The last chapter is about the most insightful thing I’ve read on sectarianism, where he talks about it as a kind of Islamic nihilism, and that as you come to see the world as essentially corrupted, this nihilism is a withdrawal from the world. It’s really something that’s happened in a lot of places that have just been demolished, whether it’s by U.S. bombs or in this case primarily by Assad and Russia’s bombs. In any case, there’s a kind of traumatised withdrawal from the world which is associated with this kind of Islamic nihilism. So, yeah that’s a book that’s very much worth reading and very insightful.

There’s a shorter article that was put up by Spectre magazine and also associated with the alliance of Middle Eastern and North African (MENA) socialists. This was written by Frieda Afary and Lara al-Kateb and it is called ‘What is Holding Back the Formation of a Global Prison Abolitionist Movement to Fight COVID-19 and Capitalism?’ So, quote:

“In the Middle East and North Africa region, Syria has the highest number of political prisoners with roughly 100,000 people. A letter signed by 43 human rights groups calls for the immediate release of all prisoners from detention centres and jails and prisons inside Syria. …

[T]here is a tendency among some on the global left to ignore or defend authoritarian rulers who claim to be against US imperialism. This selective anti-imperialism refuses to defend political prisoners in countries such as Syria, Iran, Russia, China, Venezuela, Cuba, Nicaragua even if they oppose all imperialist powers and religious fundamentalism. Of the over 100,000 political prisoners in the brutal Assad regime’s dungeons, the majority are not jihadists – they are youth, Kurdish, labour, and feminist activists who dared to participate in the uprising against the Assad regime in 2011 and after. The millions of Syrian refugees who are being bombed by the Assad regime and their Russia and Iranian allies suffer in refugee camps in the region.”

Ani White: So again, it’s this opposing prisons in the minority world or the West, and supporting or denying the existence of prisons in the majority world. As I say, I think there’s a lot to learn from the Syrian revolution,, and a lot that we’ll be learning for a long time, unless people shut their minds off on the basis that Assad is an opponent of U.S. imperialism. Which he really isn’t. One thing I found really funny was a Trotskyist who was saying, ‘I celebrate every time Assad’s soldiers kill U.S. soldiers’ and the only possible response was ‘they’re not doing that.’ Like, there is not a ground war between Assad and the U.S.. So this was a fiction that he had in mind. Maybe a slogan borrowed from Vietnam or something, and he’d obviously just not paid attention to the basics of the actual situation. So yeah, if you’ve got those kind of mental blockers you’re obviously not going to learn.

Are there any other points you want to make?

Gayaal Iddamalgoda: No, that’s a really brilliant reading list, Ani. I think we have, as you said, a lot to learn from the 2011 Arab Spring because it was an object lesson as to why the politics of Stalinists is wrong when it’s applied to the third world. It was an object lesson in how the working class in the Middle East, which has constantly been maligned in the West as being backward, sectarian, unable to understand democracy, when they came out en masse and said things like, ‘Sunnis and Alawis are one’, ‘Copts and Muslims are one’ in Egypt. These were the slogans that were coming organically from the working class, and I think it is really sad if people cannot see the class for what it is and for what it’s capable of. So I think socialists need to understand and need to keep their focus on class struggle and not give in to narrow-minded and racist dogmas.

Ani White: Yeah, ultimately it comes down to a lack of faith in the class and sort of giving up on that and saying, ‘states are the safeguard’. The two of us were involved in Syria solidarity organising in Whanganui-a-Tara, Wellington, and we organised, for example, a demonstration at the Russian embassy. You had the Syrian community coming out and young men took over the mic and were chanting Syrian Arabic chants and it was really nice to just let these young Syrian men take over the event and graffiti the Russian embassy and everything. We were criticised for protesting outside the Russian embassy and as mentioned earlier, it was like, ‘why don’t you protest outside the U.S. embassy?’ To which the response is, ‘we have, many times.’ It’s a matter of consistent solidarity, that we stand with oppressed and exploited people everywhere.

Thanks for coming on the show Gayaal.

Gayaal Iddamalgoda: Thank you, Ani. It’s been a real pleasure.

Ani White: And solidarity, comrades. Goodnight and good luck.

A review of Sylvia Pankhurst: Sexual Politics and Political Activism, Barbara Winslow, re-issued edition published by Verso Press, 2021.

A review of Sylvia Pankhurst: Sexual Politics and Political Activism, Barbara Winslow, re-issued edition published by Verso Press, 2021.

[We are re-posting this essay by Bill Fletcher because he offers a compelling response to an argument that has been circulating all too widely in left circles. We are using the version that appeared on

[We are re-posting this essay by Bill Fletcher because he offers a compelling response to an argument that has been circulating all too widely in left circles. We are using the version that appeared on

A

A

A Review of Worked Over: How Round-The-Clock Work is Killing the American Dream by Jamie K. McCallum (Basic Books, 2021); Work Won’t Love You Back: How Devotion to Our Jobs Keeps Us Exploited, Exhausted, and Alone, by Sarah Jaffe (Bold Type Books, 2021) and Dirty Work: Essential Jobs and The Hidden Toll of Inequality in America by Eyal Press (Farrar, Straus, and Giroux, 2021)

A Review of Worked Over: How Round-The-Clock Work is Killing the American Dream by Jamie K. McCallum (Basic Books, 2021); Work Won’t Love You Back: How Devotion to Our Jobs Keeps Us Exploited, Exhausted, and Alone, by Sarah Jaffe (Bold Type Books, 2021) and Dirty Work: Essential Jobs and The Hidden Toll of Inequality in America by Eyal Press (Farrar, Straus, and Giroux, 2021)

We welcome the opportunity to clarify misrepresentations of

We welcome the opportunity to clarify misrepresentations of

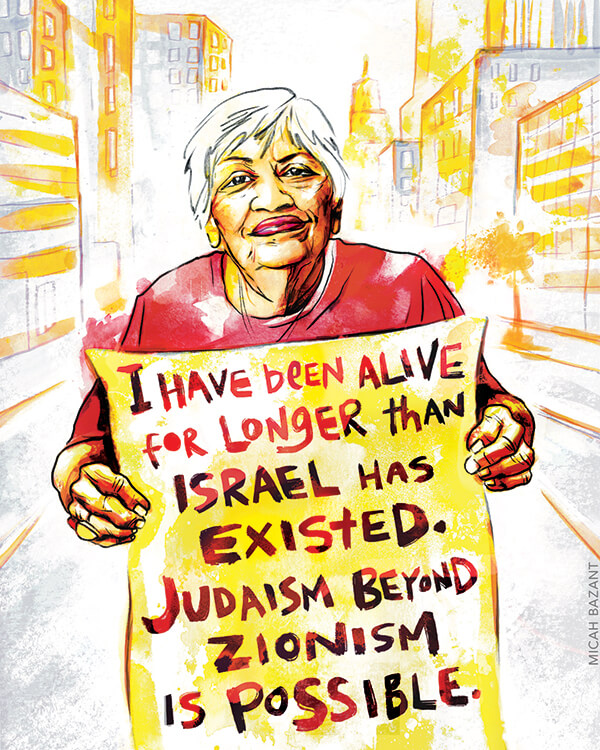

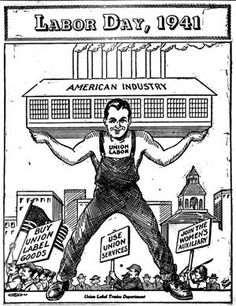

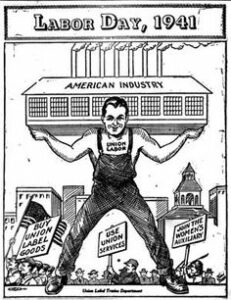

An Economic Policy Institute graph showing the relationship between union density and the concentration of wealth sends us an important message this Labor Day; however it does not, as one well-known writer argues,

An Economic Policy Institute graph showing the relationship between union density and the concentration of wealth sends us an important message this Labor Day; however it does not, as one well-known writer argues,

The September 11th attacks were the first major event I can remember. I was in Grade Eight at the time. We were all sent home where the news played scenes of the carnage over and over again like some kind of Sadean merry-go-round. Even in Canada there was panic that we might be next, with the center of Ottawa locked down and our leaders struggling to one up each other in expressions of remorse and stern concern.

The September 11th attacks were the first major event I can remember. I was in Grade Eight at the time. We were all sent home where the news played scenes of the carnage over and over again like some kind of Sadean merry-go-round. Even in Canada there was panic that we might be next, with the center of Ottawa locked down and our leaders struggling to one up each other in expressions of remorse and stern concern.