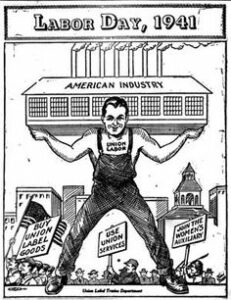

An Economic Policy Institute graph showing the relationship between union density and the concentration of wealth sends us an important message this Labor Day; however it does not, as one well-known writer argues, say it all for socialists, or those who want a revitalized labor movement, or activists who are fighting social oppression. In fact, it recapitulates the problem with the graphic for this article, a historically inaccurate nostalgia for a white, male cisgender working class.

An Economic Policy Institute graph showing the relationship between union density and the concentration of wealth sends us an important message this Labor Day; however it does not, as one well-known writer argues, say it all for socialists, or those who want a revitalized labor movement, or activists who are fighting social oppression. In fact, it recapitulates the problem with the graphic for this article, a historically inaccurate nostalgia for a white, male cisgender working class.

Seeing gender (and its intersectionality with race) in labor reveals much we need to recall this Labor Day. Black women have historically worked for pay outside the home (in addition to caring for their own families) when they could. Women worked at the start of the industrial revolution in textile mills. When urban school systems were created, women were hired as teachers, in Chicago forming Local 1 of what became the American Federation of Teachers, under the leadership of Margaret Haley. More recently teachers and nurses have often displayed a resilience and militancy defending their own working conditions and protecting those who are most vulnerable in our society that’s a model for the rest of the labor movement.

The pandemic has confronted unions with a historic challenge. COVID-19 and the response to it have simultaneously illuminated and intensified the ways “women’s work,” labor traditionally done by women in and for social reproduction, is both essential and devalued. The pandemic has exposed our dependence on people who are paid to provide physical and emotional care, along with our society’s inability and unwillingness to support and protect these workers as they risk their lives for us. From nurses, therapists, teachers, and flight attendants, to workers in jobs viewed (incorrectly) as unskilled with lower status and pay, like aides in hospitals and nursing homes, restaurant workers, and workers in hotels, it’s clear the less respect (and money) workers receive, the more disproportionately the job is done by Black, Latinx, and Indigenous people, often women. The poor pay and working conditions of much caregiving work reflect not only who is doing the care but for whom it is being done. Low-income people of color get the short end of both sides of the stick.

Social movements for equality and social justice have exposed disparities at the workplace, giving unions an opening to support workers who most need the protection collective representation brings. We see employers, from nonprofits to transnational corporations, giving verbal homage to correcting inequalities while failing to disrupt underlying inequalities in how work is organized, classified and paid. Outrage at the hyper-exploitation of food delivery services forced some of the most exploitative businesses to modify practices, stating clearly that delivery fees weren’t going to workers and providing ways for customers to tip. We should be fighting for the “gig economy” workers in food services, many of them immigrants, to earn a living wage and have stable hours. Still even among these hyper-exploited workers there’s a gender divide. The apps and websites allow customers to tip the workers who do deliveries (mostly young males of color) while the workers who prepare, pick and package food (traditionally women’s work) remain invisible and subject to whims of employers about wages.

Labor Day invites us to commemorate significant contributions unions have made for working people, recognizing courageous sacrifices of workers who lost their jobs and sometimes their lives fighting for the right for us to have collective voice at the workplace and to force both political parties to pass legislation limiting employers’ exploitation. At the same time, we confront sobering realities of how many advances have been undercut, as labor’s economic and political power and its numbers waned, due in part to widespread acceptance of “business unionism,” which makes workers clients served by a union apparatus, rather than “owners” of their unions. The pandemic has created a global opportunity for disaster capitalism to mask policies that increase exploitation – and profits — in rhetoric about addressing longstanding social inequality. One ominous change is the chilling intensification, development and application of information technology to control workplace conditions; provide social, health and educational services; increase surveillance and data mining; and replace workers with AI.

Employers applaud themselves for boosting the prominence and authority of individuals from historically marginalized groups, substituting this shared power at the top in dominating workers, instead of supporting workers’ voice and empowerment through unionization. In contrast, when workers organize collectively, independent of the employer, they challenge the employer’s unilateral control over life at work, from pay and hours to the air they breathe, which in the pandemic is literally a matter of life and death. Collective organization brings potential power, which depends on the extent to which workers control what unions do in their name. Unions are only as strong as workers’ understanding that they, not union staff or officials, “own” their organizations.

It’s important not to romanticize workers and diminish the enormity of what we ask. Given the harsh conditions for work, expecting working people to do the jobs for which they are paid and also help organize their workplaces is a huge ask. One invaluable asset we have is seeing the inseparability of struggles for social justice and workplace democracy. We don’t dilute our power to improve economic conditions when we fight for demands to make our society and workplace more equitable, just and humane. On the contrary, we benefit from the synergy of increased resources and networks, often missed even when unions organize and defend workers who do “women’s work,” missing the gendered nature of work. UNITE HERE’s campaign opposing Hilton Hotel’s elimination of the daily requirement for cleaning rooms, putting housekeepers’ jobs in jeopardy, rightly highlights how this harms communities of color and low-wage women workers. Still it misses how housekeeping can be eliminated so easily: “women’s work,” cleaning the home, is taken for granted. What’s assumed is that no one will miss the work that’s done or the people doing it.

When Liz Shuler, the newly elected president of the AFL-CIO, who proudly claims the mantle as first woman to hold this position, tweets “I am humbled, honored and ready to guide this federation forward. I believe in my bones the labor movement is the single greatest organized force for progress,” she expresses what should be our hope and vision. Yet labor officialdom’s actions often undercut our chances of success in making that vision a reality. For example, the AFL-CIO has focused almost all of its energy on passing the PRO Act, and while the legislation is important, we can’t assume its passage will solve labor’s problems. Labor can’t rely on Biden and the Democrats’ promises of legislation to substitute for workers fighting for what they want and need, for themselves and the society.

What is it we should expect and demand of unions? When a hospital starts to hire “replacements” for striking nurses in Worcester, Massachusetts, who have been on the line for months, insisting on conditions that protect patients, the state and national AFL-CIO need to speak up for a state-wide one-day walkout – and provide resources to organize it. When teachers and staff demand school districts change policies to help keep schools safe, reflecting new dangers brought on by the Delta variant, they deserve to have the state and national teachers unions show up with resources for organizing one-day statewide walkouts and protests. One teacher union activist, who like others is organizing to make his district and state spend their federal pandemic funding on what students really need, observed the national teacher unions have the most influence over the White House than we’ve had in a generation, and yet both national unions, AFT and NEA are “working as mouthpieces for the administration instead of pushing the envelope.”

Movements fighting for social justice, from “#MeToo” to BLM to “AbolishIce” need a massively reinvigorated labor movement, just as much as labor unions need them. We need new understandings and enactments of solidarity that recognize how social oppression affects us all. Unions are stronger when they acknowledge the political tensions that exist among union members and provide democratic spaces to hammer out differences, in the process of deciding on specifics for fighting back. When we use our power on the job to force those who exploit us to hear, value, respect our humanity, we are demanding a new world. The challenge workers and their organizations face is not so different from what women must accomplish when they go into labor: arduous work that requires courage, confidence and hope, the work essential for birthing a new society, which we need and deserve.

A version of this article appeared in Truthout.

Editor’s note: Labor Day 2021 marks the start of the New Politics special fund appeal. This year we have an especially ambitious goal, raising $10,000 for updating our website, making the entire archive of back issues available on our site, purchasing software to manage the growing number of subscriptions and donations, and improve communication among the editorial board, NP’s supporters, and our generous writers. We are counting on our readers to help us. You can donate here.

Leave a Reply