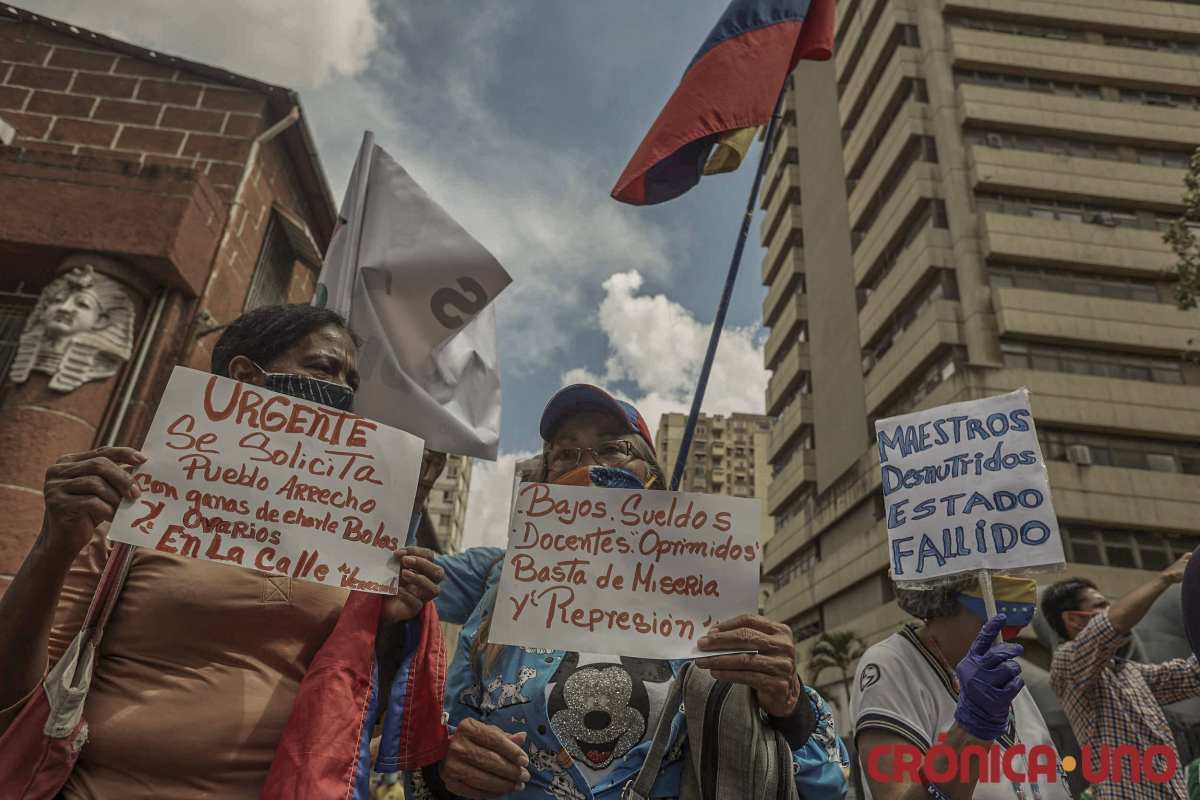

Iraqi security forces firing tear gas and live rounds into a crowd of demonstrators during the 2019 Tishreen (October) uprising

The last decade has seen historic political upheavals across the Middle East and North Africa: a tsunami of popular uprisings that have brought down several dictators and led to momentous transformations in political consciousness, if not always to democratic outcomes. But the last decade has also seen a concomitant counter-revolutionary roll-back across the region: authoritarian regimes, entrenched elites, ruling classes, deep states, and reactionary forces have marshalled considerable resources to torpedo these movements from below.[1]

Saudi Arabia’s role as a counter-revolutionary force in the Middle East is widely understood and thoroughly documented. Historian Rosie Bsheer calls the Saudi kingdom “a counter-revolutionary state par excellence,” indeed one that was “consolidated as such.”[2] The Saudi monarchy has gone into counter-revolutionary overdrive since the onset of the Arab uprisings, scrambling to thwart popular movements and keep the region’s dictators in power — from Egypt and Bahrain to Yemen and Sudan (and beyond).[3]

What is less understood is the counter-revolutionary role that Iran plays in the region’s politics. This is poorly understood and under-examined because it flies in the face of the dominant narrative, that of Iran as a “revolutionary” state in the vanguard of a regional “Axis of Resistance” to US imperialism and its allies. This view is shared across the ideological spectrum, from neoconservatives and US foreign policy hawks (for whom Iran’s “revolutionary” policies are dangerous and must be contained/confronted) to large swaths of the “anti-imperialist” Left and antiwar movement (for whom Iran is merely defending itself and “resisting” US/Israeli/Saudi belligerence). While the two camps disagree about whether Iran’s “revolutionary” agenda is a good thing, they agree that it is “revolutionary.” This is also the official line of the Islamic Republic itself, whose self-image as a “revolutionary” state in the vanguard of an “Axis of Resistance” is central to its identity — and legitimacy.[4]

Here we have a classic instance of what the sociologist Ulrich Beck calls a zombie category. Zombie categories, he argues, “are dead but somehow go on living, making us blind to the realities” of the world.[5] The view of Iran as a “revolutionary” state has been dead for quite some time yet somehow stumbles along and blinds us to what is actually happening on the ground in the Middle East. A brief look at the role Iran has played over the last decade in three countries — Lebanon, Iraq, and Syria — reveals a very different picture: not one of a revolutionary but rather of a counter-revolutionary force.

Lebanon’s “October Revolution”

In October 2019, hundreds of thousands of people took to the streets across Lebanon in “the most comprehensive anti-government protests the country has seen at least since the civil war ended in 1990, in terms of numbers, geographic spread, and diversity of sects and class.”[6] While the proximate causes were the government’s inept response to the wildfires that engulfed the country and its announcement of a tax on WhatsApp voice calls, the uprising — which came to be known as Lebanon’s “October Revolution” — had deeper roots and gave expression to grievances that had been simmering for several years. The 2015 “You Stink” protests against the disfunction and mismanagement that led to a crisis of uncollected garbage, for instance, in many ways prefigured the 2019 uprising.[7] But the 2019 demonstrations were more far-reaching: people throughout the country — “not only in Beirut but in all major coastal cities and smaller inland ones” — took to the streets “in a show of solidarity never before seen.”[8] They were “rebelling against the socioeconomic violence…produced by the sectarian order” with its “rampant clientelism and corruption,” notes Lebanese political scientist Bassel Salloukh.[9] Along similar lines, Lebanese sociologist Rima Majed characterizes it as a revolt against “sectarian neoliberalism.”[10]

Mass demonstration in Beirut during Lebanon’s 2019 “October Revolution”

There were three distinct “streams” within the uprising, according to Majed. What she calls the “radical” stream “has been thinking intersectionally, centering class inequality, gender inequality…questions of citizenship, race, and refugees. It is mobilizing around all these issues and making links between them, and demanding an overhaul of the neoliberal economic system as well as the sectarian political system.”[11] Majed and Lana Salman note the centrality of a feminist politics in the uprising, one that aims to “dismantle interlinked manifestations of patriarchy, capitalism and sectarianism.”[12] Majed characterizes the second stream as essentially “liberal” and the third stream as “more ad hoc,” lacking a “clear political project or vision.” A spectrum of orientations was thus present in the Lebanese uprising, with a decidedly progressive center of gravity.

Close to a million people — a critical mass in a country of less than 7 million — participated in the demonstrations. An embodiment of what Yasser Munif calls “the politics of life”[13] or what Asef Bayat calls “the politics of fun,”[14] Jade Saab and Joey Ayoub describe the “carnival atmosphere” in Lebanon’s public squares, “with music, dancing, DJs and fireworks at night” and a vibrant intellectual scene with “daily public lectures on the economy, the constitution, history,” and other themes.[15]

“In these ‘classes’ you could see attempts at the creation of a new Lebanese identity,” Saab and Ayoub observe — one that rejects and transcends the “myths of sectarianism.” In the same vein, Salloukh sees Lebanon’s “October Revolution” as a “truly foundational moment” in which “people are redefining their subjectivity.”[16] The uprising, he notes, “has allowed for a reimagining of the Lebanese nation beyond top-down imposed narrow sectarian affiliations.” He detects

a shift in how people define themselves as agents: not as sectarian subjects in a political order cut along sectarian and religious lines, but rather as anti- and trans-sectarian citizens operating in a polyphonic and democratic civic space.…[17]

Counter-revolution

Where does Hezbollah, Iran’s key ally in Lebanon, figure in this picture?

The defining slogan of Lebanon’s uprising — “all of them means all of them” (kellon yani kellon) — called out the country’s entire ruling class, which includes Hezbollah. One pointed variation on the slogan was “All of them means all of them, and Nasrallah is one of them.”[18] Protesters chanting “the people want the downfall of the regime” (the defining slogan of the 2011 Arab uprisings) gathered outside the office of Mohammed Raad, the head of Hezbollah’s parliamentary bloc.

Hezbollah returned the favor: after some initial hedging, the “Party of God” unleashed a mob on Beirut’s main protest site, beating unarmed activists at a peaceful sit-in and burning down their tents.[19] In the southern Lebanese town of Nabatiyeh, according to Human Rights Watch, several hundred Hezbollah supporters “attacked peaceful protesters, with sticks and sharp metal objects, including beating women, children, and older people indiscriminately.”[20] In response to that assault, protesters declared a “day of solidarity with Nabatiyeh” on October 24.[21] “Those who oppress Beirut don’t liberate Palestine,” read graffiti scrawled in downtown Beirut in a poignant critique of Hezbollah.[22]

A Hezbollah supporter (right) attacks a protester at Beirut’s main protest site amid Lebanon’s 2019 uprising. “Party of God” supporters burned down the tents at the encampment and attacked protesters in other Lebanese cities.

Hezbollah’s attacks on the demonstrators were not only physical but rhetorical, framing the popular revolt as part of a foreign plot against Hezbollah and its regional allies in the “Axis of Resistance” — accusations that were “met with ridicule, especially since it was being spearheaded by a party that openly flouts the fact that it is almost exclusively funded by Iran.”[23] Activists fired back with satire, “distributing free sandwiches with ‘funded by [name of foreign government]’ written on them.”[24] Nasrallah is “coming up with conspiracy theories just to get people to stop revolting,” a university student active in the protests, Ahmad Bshennaty, told Al Jazeera.[25] Tehran amplified this line, blaming the protests on “America and Western intelligence services” and warning of the “insecurity and turmoil” they portended.[26] Supreme leader Ali Khamenei invoked a highly revealing domestic comparison: in an apparent reference to the mass protests that rocked the Islamic Republic in late 2017 and early 2018, he said that foreign powers “had similar plans” for Iran, but “the armed forces were ready and that plot was neutralized.”[27]

This “campaign against the protests,” Salloukh notes, “backfired among the public, even inside the Shi‘a community, for it portrayed Hezbollah as the main defender of the sectarian system with all its corruption and distortions.”[28] Hezbollah is “now viewed by many demonstrators as part of the corrupt and morally bankrupt political establishment that must be replaced,” as Joseph Haboush observes.[29] Lebanese activist and podcaster Nizar Hassan characterizes Hezbollah’s role in the uprising as that of a “counter revolutionary guard.”[30]

Hezbollah’s aim was to “end the protest movement by proposing solutions that maintain the Lebanese sectarian and neoliberal framework, while continuing to use intimidation and sometimes violence against protesters,” writes Joseph Daher, author of a book on Hezbollah.[31] Although Hezbollah has been firmly entrenched in Lebanon’s power structure for over a decade — Lebanese author Elias Khoury calls it “the system’s staunchest supporter”[32] — the 2019 upheaval brought what Daher calls “the contradiction between Hezbollah’s proclaimed support for the ‘oppressed’ and its orientation favourable to Lebanese neoliberalism and the country’s elite class” into ever sharper focus.

The Lebanese writer and podcaster Joey Ayoub captures the Orwellian upside-down-ness of this ideological sleight of hand in his formulation “Hezbollah’s Resistance™ against resistance.”[33] Hezbollah, he shows, tries to have it both ways: on the one hand, defending the status quo and maintaining Lebanon’s “sectarian-capitalist structures,” while at the same time banking on its membership in the so-called “Axis of Resistance.” That is, posturing as a force for “resistance” — a zombie category amid Lebanon’s current political landscape — while attacking people engaged in actual resistance to the ruling system and undermining progressive social movements.

Iraq’s Tishreen uprising

The parallels between the Iraqi and Lebanese revolts are manifold, starting with their timing: mass protests engulfed both countries starting in October 2019. Iraqi and Lebanese protesters were conscious of the connections between their struggles: “in the different protest squares people are shouting: ‘One revolution, from Baghdad to Beirut,’” notes Sami Adnan, an activist in Baghdad with the group Workers Against Sectarianism.[34] It’s also important to see the two upheavals in their wider regional context, as part of the “second wave” of Arab uprisings that also included momentous popular movements in Algeria and Sudan — or, as some argue, the uprisings that have been ongoing across the Middle East and North Africa since December 2010.[35] Moreover, all four of these cases were part of a global wave of simultaneous mass protests in late 2019 — in Chile, Hong Kong, India, France, Ecuador, Guinea, Haiti, Colombia, Iran, Argentina, and beyond — which could be “the largest wave of nonviolent mass movements in world history.”[36]

The protests that erupted in Iraq in October 2019 were arguably the “biggest grassroots socio-political mobilization” in the country’s history.[37] At root, that mobilization was “about the poor, the disempowered and the marginalized demanding a new system,” notes the Iraqi sociologist Zahra Ali.[38] The Tishreen (October) uprising, as it came to be known, quickly spread to “cities and towns across central and southern Iraq”[39] and eventually “engulfed virtually the whole country (though they were most concentrated in Baghdad and the Shia-dominated southern governorates).”[40]

By no means did this upheaval come out of nowhere: Iraq has seen a steady stream of protests in recent years — in 2009, 2011, 2015, and 2018.[41] But the 2019 protests represented “the most serious challenge yet to the post-2003 political order,” the Iraq scholar Fanar Haddad observes.[42] The 2019 rebellion was “backboned” by those previous protests — it was the “culmination of a decade of mobilization”[43] — “but its identity was more radical and firmer,” notes Zeidon Alkinani.[44] “People were no longer asking for better job opportunities, electricity or water. They were calling to overhaul the system.”

Alkinani underscores that the movement “classified itself as a ‘revolution’ in terms of discourse, demands, and objectives.” “[E]ven if the current movement fails to achieve a political revolution,” Haddad argues, “and even if it is not a revolution, it is undoubtedly a revolutionary movement that has already achieved a cultural revolution.”[45]

An Iraqi activist being blanket-tossed into the air by fellow demonstrators in Baghdad’s Tahrir Square, the site of what Fanar Haddad calls an “explosion of cultural, political and intellectual expression and creativity” (December 2019)

What were the protesters calling for? First and foremost, “eradicating the Muhasasa system,” Alkinani notes, referring to the ethno-sectarian scheme in which political representation and power are based on sub-national identities (Shi‘a/Sunni/Kurd).[46] This system — established under the US occupation following the 2003 invasion and sustained by both American and Iranian influence in the years since — became “the target of popular rage,” Haddad notes: “rage at the systemic failures, dysfunction and criminality that have marked the post-2003 order.” That order has created a massive chasm, Haddad observes, between “the ruling few and those with connections to them” on one hand and “the vast majority of impoverished and excluded Iraqis” on the other.[47] In 2019, those impoverished and excluded Iraqis rose up “demanding a whole new system,” Zahra Ali and Safaa Khalaf write.[48]

As in Lebanon, Asef Bayat’s “politics of fun” was on full display in Iraq, especially in the epicenter of the 2019 protest movement, Baghdad’s Tahrir Square, home to an “explosion of cultural, political and intellectual expression and creativity,” writes Haddad.

Amidst a forest of tents blaring everything from hip hop to poetry to Shia mourning recitations, reminders of why Iraqis have taken to the streets, and at what cost, abound in the form of pictures, murals, memorials, prayer meetings and other forms of commemoration dedicated to the young men who lost their lives over the course of the past two months of mass mobilisation.[49]

And like Lebanon, the uprising involved an intellectual component. “Tahrir Square in Baghdad today is a revolutionary zone,” says the aforementioned Baghdad-based activist Sami Adnan.

There are places for reading books in one tent, and a medical tent. Some tents represent specific regions of Iraq, or retired people, or professional groups, like unions of engineers, etc. … [People] discuss day-to-day things about what to do, but also questions of leadership, writing a new constitution, or putting on seminars about different political topics.[50]

“A new political awareness and culture have been formed” through the protests, Haddad writes.[51] Indeed, Alkinani argues, the uprising has “opened a new chapter in Iraq’s modern history.”[52] The Tishreen uprising has “opened the door to a new Iraqi identity and national consciousness,” proclaim the editors of Tuk Tuk, a newspaper that grew out of the revolt, on the front page of its second issue.[53]

Counter-revolution

As Berman, Clarke, and Majed note:

A movement demanding wholesale political change represented a real threat to the system of cronyism and rapaciousness that has enriched Iraq’s politicians over the last two decades, and these elites quickly mobilized an array of state and non-state security agents in an attempt to quash this challenge.[54]

Mohammad al Basri, a figure affiliated with Iraq’s paramilitary Popular Mobilization Units, expressed this mindset with rare bluntness: “Do they really think that we would hand over a state, an economy, one that we have built over 15 years? That they can just casually come and take it? Impossible! This is a state that was built with blood.”[55]

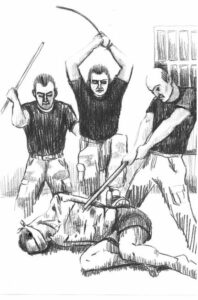

Those forces wasted no time in launching a “war against unarmed protesters” that left several hundred dead and several thousand wounded.[56] Amnesty International documented the use of “military-grade tear gas grenades, live ammunition and deadly sniper attacks”[57] in what the organization calls a “lethal campaign of repression against protesters” and an “ongoing wave of intimidation, arrests and torture” of Iraqi activists.[58] Whereas this bloodbath of repression against crowds of protesters has been perpetrated in broad daylight, an ominous chain of assassinations targeting activists connected to the uprising has been happening in the shadows, creating what protesters call “an atmosphere of terror.”[59]

Protest art in Baghdad depicting a demonstrator hit by a tear gas canister during the 2019 Tishreen (October) uprising. A striking array of murals, graffiti, and public art has sprung up within Iraq’s protest movement.

The uprising has been “profoundly shaped by the Iraqi security forces’ violent repression,” Ali and Khalaf observe.[60] Indeed, Haddad notes, the demands of the protesters were “only hardened by the violence that has been unleashed on them.”[61] “The more the political establishment cracked down on protests, the more outrage it triggered, resulting in fresh rounds of mobilization,” write Chantal Berman, Killian Clarke, and Rima Majed.[62]

Iran is deeply implicated in this counter-revolutionary repression — both indirectly, as the chief political ally and patron of the Iraqi government over the last 15 years, and directly, through the web of militias and paramilitary forces coordinated by the Quds Force of the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC), which have opened fire on protesters.[63] Those militias “committed bloody massacres against peaceful protesters” in multiple Iraqi cities, including Baghdad, Nasriyah, Basra and Najaf.”[64] “The authorities, paramilitary forces and militias connected to the political elite, backed by Iran, are those primarily responsible for killing, beating, threatening and intimidating demonstrators, civil society activists and journalists,” Zahra Ali notes.[65]

Tehran also intervened politically, maneuvering to keep Iraqi Prime Minister Abdel Abdul Mahdi in power in the face of demands from protesters that he step down.[66] (Mahdi eventually did resign, in late November 2019 — a major victory for the protest movement that Tehran endeavored to circumvent.)

Iraqi protesters weren’t just rebelling against Iran’s local allies, but against Iran itself. Protesters in Baghdad’s Tahrir Square smashed banners of Khamenei with their shoes.[67] Others put up a white banner with red Xs drawn through photographs of Khamenei and Quds Force commander Qasem Soleimani, the architect of Iran’s regional policy.[68] “Images of Ayatollah Khomeini were removed from cities like Najaf, and pro-Iran political parties with prominent militias that were involved in the violence against the protesters had their branch offices attacked and burned,” Alkinani notes.[69] Most spectacularly, protesters set fire to the Iranian consulate in Karbala and Najaf amid chants of “Iran out of Iraq”.[70]

Among the demands of the protesters, Adnan notes, are “an end to the rule of militias, and an end to corruption and foreign rule — especially Iranian rule, but also US rule.”[71] “Most Iraqis are increasingly outraged at the way their national sovereignty is constantly infringed” by both Washington and Tehran, notes Middle East scholar Gilbert Achcar.[72] Vividly illustrating this point, Haddad observes that in Baghdad’s Tahrir Square,

while gazing at a mural proclaiming ‘America go out of Iraq’ complete with a depiction of an American dagger bleeding Iraq dry, a looped recording of a voice chanting ‘Iraq is under Iranian occupation’ can be heard.[73]

The Associated Press reported that the very day after the protests began in Iraq in October 2019, Soleimani flew to Baghdad in a helicopter for an emergency meeting with high-ranking Iraqi security officials. According to two of those officials, Soleimani said to them in that meeting: “We in Iran know how to deal with protests. This happened in Iran and we got it under control.”[74]

Despite the many parallels between the Lebanese and Iraqi uprisings, there are two key differences: (1) the protests in Iraq were met with a staggering level of violence, in contrast to the largely nonviolent Lebanese case; (2) Iran played a much more direct role in the Iraqi counter-revolution than it did in Lebanon, where its key ally, Hezbollah, represents and reflects the stance of the Islamic Republic. But what both cases illuminate is this: in the face of popular uprisings expressing emancipatory demands, Iran sides not with the protesters but with the ruling establishments they’re protesting against. And the story is far from over: while the COVID pandemic dampened protests, the issues that gave rise to the uprisings remain unresolved, and activism in both countries continues.[75]

Syria’s forgotten revolution

Moving in reverse chronological order, I’ll now briefly examine Iran’s response to the Syrian uprising in 2011. I will not examine Iran’s role in the Syrian conflict writ large; rather, my focus will be on Iran’s response to the initial, nonviolent phase of the Syrian uprising, from the spring to the autumn of 2011.

With the colossal violence that has engulfed Syria over the last decade, it is often forgotten that it all began with peaceful protests expressing democratic demands. In March 2011, mass demonstrations broke out across the country — in provincial villages and urban areas alike. Syrians representing a cross-section of the country (Sunnis, Alawites, Christians, Druze, Ismailis, Kurds, and others) took to the streets chanting slogans that echoed those of their counterparts in Tunisia, Egypt, and elsewhere across the region, and expressing the same aspirations — for freedom, dignity, social justice, democratic rights, and an end to dictatorship. Because this history has been largely obscured by the calamity that befell Syria, buried under the rubble of the tragedy — in some cases it has been actively erased in the war of narratives over the conflict[76] — it’s critically important to take stock of the emancipatory, visionary, pluralistic, and radically democratic goals of the Syrian uprising. This is not the place for an in-depth discussion of that story, but I want to point to the rich literature on the subject, and to the vital archival and storytelling work of websites like SyriaUntold, Creative Memory of the Syrian Revolution, and 100 Faces of the Syrian Revolution.[77]

Iran’s official narrative is that its role in Syria is all about fighting terrorism — specifically Al Qaeda and ISIS. But this is a classic case of reading history backwards. In fact, Iran rushed to the defense of the Assad regime as soon as the uprising began — when there was no Al Qaeda or ISIS presence whatsoever (the only jihadists were the ones the regime intentionally let out of its prisons as part of its jihadization strategy).[78] “From the very moment Assad faced popular protests, the Quds Force and Tehran were ready to do all they could to save the rule of the Baath Party,” notes Arash Azizi. Indeed, the Islamic Republic’s emissaries “were pushing on Assad to suppress the uprising mercilessly.”[79] And that is precisely what the regime did. As I wrote in 2016:

The Assad regime’s response to those peaceful demonstrations across Syria in 2011 can be summed up in two words: live ammunition. The regime’s security forces fired on crowds of unarmed protestors for upward of six months. The Islamic Republic defended its staunch ally in Damascus, as the latter unleashed a bloodbath of repression against a popular and nonviolent democratic uprising.[80]

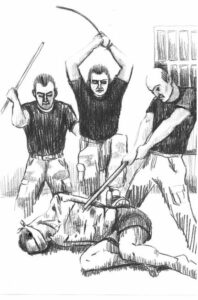

Sketch of one of many torture techniques used in the Assad regime’s dungeons (from the Human Rights Watch report Torture Archipelago: Arbitrary Arrests, Torture and Enforced Disappearances in Syria’s Underground Prisons since March 2011)

In his book The Battle for Syria, Christopher Phillips reports that Ali Akbar Salehi, Iran’s foreign minister at the time, “made numerous trips to Damascus to reassure Assad.” Tehran, Phillips notes, provided riot equipment to the Assad regime and dispatched hundreds of Quds Force operatives “to offer security advice.”[81] Jubin Goodarzi, author of Syria and Iran: Diplomatic Alliance and Power Politics in the Middle East, adds:

Iran provided technical support and expertise to neutralise the opposition; advice and equipment to the Syrian security forces to help them contain and disperse protests; and guidance and technical assistance on how to monitor and curtail the use of the internet and mobile phone networks by the opposition. Iran’s security forces had learned valuable lessons in these areas during the violent crackdown against the opponents of President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad that followed the disputed presidential elections of June 2009.[82]

Iran expert Reza Marashi offers a similar analysis. The Islamic Republic’s “first reaction” to the demonstrations in Syria “was to open its own playbook and show Assad pages from the post-election protests in 2009,” he observes. “Decision-makers appear to have hoped that Assad would use enough brute force — arrests, beatings, and a limited amount of killings — to spread fear and quickly re-establish control.”[83]

This “security advice” was augmented by a narrative strategy: Iran helped flip the script and present the Syrian protests not as part of the wave of Arab uprisings — which it decidedly was — but as a foreign-inspired terrorist plot. This rhetorical framing was awkward for the Islamic Republic, which had voiced support for other Arab uprisings — those in Tunisia, Egypt, Bahrain, and Libya. This put Tehran in a bind, praising the people of the region for rising up against the dictators that oppressed them but siding with the dictator in Syria.[84] Amin Saikal characterizes this Syrian exception as “an intervention that ran counter to Tehran’s declared rhetoric of supporting the downtrodden masses.”[85]

Ewan Stein notes that Iran (and its ally Hezbollah) committed to “denying the democratic aspects of the [Syrian] revolution and instead casting it as a terrorist insurgency.” “In so doing,” Stein observes, “they appropriated the discourse of the [Global War on Terror].”[86] This framing allowed Iran to present itself as being on the “right” side of the Syrian conflict: fighting extremists. The militarization and sectarianization of the conflict[87] — processes of which the Assad regime was the principal (though not exclusive) driver — were a godsend for Iran’s war on terror framing: a self-fulfilling prophesy that was very much by design.

Iran has projected this framing backwards, as if fighting terrorists had always been its mission in Syria. But this sleight of hand leaves a fundamental question unanswered: why was the Islamic Republic on the side of the Assad regime when it was shooting, detaining, torturing, and disappearing peaceful demonstrators[88] whose demands and vision were decidedly democratic and emancipatory, well before any jihadist groups were present? And let’s be clear: the Islamic Republic intensified its support for the Assad regime in 2011 but its stalwart support for the dynastic dictatorship in Damascus goes back several decades — and while the Assad regime exponentially heightened its level of repression in 2011, violence has been at the very core of its rule throughout.[89]

The answer is that Iran’s rhetorical posturing aside, its response to the popular uprising in Syria revealed its increasingly counter-revolutionary role in the region — a development that would come into sharper focus with the Lebanese and Iraqi uprisings of 2019-2020.

Paradigms Lost: Time to Dispense with Zombie Categories

Azizi characterizes the contours of Iran’s post-2011 regional policy as follows:

Iran would orient itself to the Arab Spring not in the spirit of revolutionary fraternity but with cold calculation worthy of a scheming monarch. Despite the words that came out of his mouth, Khamenei was now more of a sultan than a revolutionary.[90]

The Islamic Republic is out “not to foster revolutions against dictators,” Azizi notes, but “to preserve its own regime and spread its influence by any means necessary.”[91] Along these lines, Borzou Daragahi observes, “[t]he ‘revolutionary’ slogans of Iran’s ‘resistance’ are empty rhetoric that merely back whatever policies benefit the corrupt ruling elite in Tehran.”[92] In the same vein, Stein argues that the so-called Axis of Resistance, “ostensibly dedicated to furthering the emancipatory aspirations of the Arab and Muslim masses,” has in reality “played a critical role in containing regional revolution and preventing the emergence of a more democratically oriented regional order.”[93]

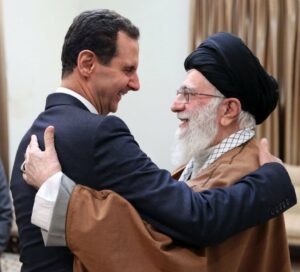

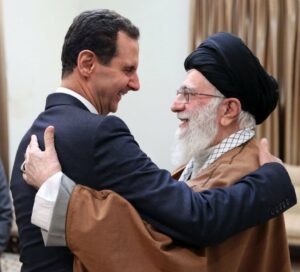

Syria’s dictator Bashar al-Assad and Iran’s Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei

Indeed, for all the talk of Iran’s “disruptive” role in the region, what the cases of Syria, Iraq, and Lebanon reveal is instead an Islamic Republic hell-bent on keeping entrenched political establishments and ruling classes in power while helping them quell popular movements for social justice, democratic rights, and human dignity. In an insightful essay, Rami Khouri notes this growing disconnect between ideological rhetoric and political reality, in which “‘resistance’ troops try to beat down ‘revolutionary’ protests” across the Middle East.[94]

This development has yet to be properly theorized, but it has not gone unnoticed. Saikal, for example, notes “Iran’s growing shift towards being a middle power supportive of the status quo.”[95] The Islamic Republic “sounds more and more like those same sclerotic rulers it once railed against,” Daragahi observes — “suspicious of any new development that threatens the status quo it dominates.”[96] Even Edward Wastnidge, in a highly sympathetic account of the Islamic Republic’s regional policies, acknowledges that Tehran “is trying to maintain the post-2003 status quo, which has seen its influence in the region grow.”[97]

We need to revise our lexicon to reflect that post-2003 status quo. We need to retire zombie categories — like that of Iran as a “revolutionary” force in the Middle East, and the fiction of the “Axis of Resistance” (a term that should always appear in quotes or be qualified by “so-called,” if not dropped altogether) — that function as distorting mirrors and mystifications.

The idea that Iran is a revolutionary power while Saudi Arabia is a counter-revolutionary power in the region is a stale binary. Both the Islamic Republic and the Saudi Kingdom play counter-revolutionary roles in the Middle East. They are competing counter-revolutionary powers, each pursuing its counter-revolutionary agenda in its respective sphere of influence within the region.

Christopher Davidson speaks to this dynamic when he observes that “Saudi Arabia and Iran’s respective forms of authoritarian theocracy continue to serve as brakes on any prospects for meaningful reform in the wider Middle East.” Both the Saudi Kingdom and the Islamic Republic, Davidson argues, “have an equally vested interest in maintaining the counter-revolutionary status quo in the territories they now contest.”[98]

The counter-revolution confronting the Middle East today in this period of dramatic upheaval is not headquartered in a single capital. Riyadh and Tehran form what we might think of as a regional counter-revolutionary hydra. (Abu Dhabi also belongs in the regional counter-revolutionary discussion — a development worthy of more research than it has yet generated.) With signs now pointing to some sort of rapprochement between the Saudi Kingdom and the Islamic Republic,[99] Davidson’s argument about the counter-revolutionary roles of both states might become less counter-intuitive: the rivalry between the regional hegemons has obscured what the two states share in common.

Danny Postel is Assistant Director of the Center for International and Area Studies at Northwestern University and a member of Internationalism from Below. He is the author of Reading Legitimation Crisis in Tehran (2006) and co-editor of The People Reloaded: The Green Movement and the Struggle for Iran’s Future (2010), The Syria Dilemma (2013), and Sectarianization: Mapping the New Politics of the Middle East (2017). Formerly Senior Editor of openDemocracy, his work has appeared in Boston Review, The Cairo Review of Global Affairs, Democracy: A Journal of Ideas, Democratic Left, Dissent, The Guardian, In These Times, Middle East Report (MERIP), The Nation, New Politics, and The Progressive, among other publications.

This essay also appears in the Occasional Paper series published by the Center for Middle East Studies at the University of Denver. The pdf is here.

Notes

[1] See Jean-Pierre Filiu, From Deep State to Islamic State: The Arab Counter-Revolution and its Jihadi Legacy (Hurst, 2015). Also see the interview with Filiu about the updated and expanded French edition of the book (Généraux, Gangsters et Jihadistes: Histoire de la Contre-Révolution Arabe), “Their Dirty Business,” Diwan, 21 May 2018.

[2] Rosie Bsheer, “A Counter-Revolutionary State: Popular Movements and the Making of Saudi Arabia,” Past & Present, Volume 238, Issue 1 (Feb. 2018), p. 240.

[3] See Toby Matthiesen, Sectarian Gulf: Bahrain, Saudi Arabia, and the Arab Spring That Wasn’t (Stanford University Press, 2013); John M. Willis, “Operation Decisive Storm and the Expanding Counter-Revolution,” Middle East Report Online (MERIP), 30 Mar. 2015; and Madawi Al-Rasheed, “Sectarianism as Counter-Revolution: Saudi Responses to the Arab Spring,” in Nader Hashemi and Danny Postel (eds.), Sectarianization: Mapping the New Politics of the Middle East (Hurst, 2017).

[4] See Shabnam J. Holliday, Defining Iran: Politics of Resistance (Routledge, 2011) and Ali Fathollah-Nejad, Iran in an Emerging New World Order: From Ahmadinejad to Rouhani (Palgrave Macmillan, 2021), especially chap. 3 (“Iranian Geopolitical Imaginations: A Critical Account”).

[5] Ulrich Beck, “Goodbye to all that wage slavery,” New Statesman, 5 Mar. 1999. Also see Jonathan Rutherford’s interview with Beck, “Zombie Categories,” in Jonathan Rutherford (ed.), The Art of Life (Lawrence & Wishart, 2000).

[6] Kareem Chehayeb and Abby Sewell, “Why Protesters in Lebanon Are Taking to the Streets,” Foreign Policy, 2 Nov. 2019.

[7] See Bassel F. Salloukh, “Lebanese protesters united against garbage… and sectarianism,” Monkey Cage (Washington Post), 14 Sept. 2015.

[8] Jade Saab and Joey Ayoub, “The Revolutionizing Nature of the Lebanese Uprising,” in Jade Saab (ed.), A Region in Revolt: Mapping the Recent Uprisings in North Africa and West Asia (Daraja Press, 2020), p. 119.

[9] Bassel F. Salloukh, “Here’s What the Protests in Lebanon and Iraq are Really About,” Monkey Cage (Washington Post), 19 Oct. 2019. For an elaboration of Salloukh’s analysis of Lebanon’s ruling system, see his co-authored volume The Politics of Sectarianism in Postwar Lebanon (Pluto Press, 2015) and his chapter “The Architecture of Sectarianization in Lebanon” in Hashemi and Postel (eds.), Sectarianization.

[10] Rima Majed, “Sectarian Neoliberalism and the Uprising,” in Jeffrey G. Karam and Rima Majed (eds.), The Lebanon Uprising of 2019: Voices from the Revolution (I.B. Tauris/Bloomsbury Academic, forthcoming).

[11] Shireen Akram-Boshar, “The Lebanese Uprising Continues: An Interview with Rima Majed,” Jacobin, 17 Feb. 2020.

[12] Rima Majed and Lana Salman, “Lebanon’s Thawra,” Middle East Report (MERIP) 292/3 (Fall/Winter 2019).

[13] Yasser Munif, The Syrian Revolution: Between the Politics of Life and the Geopolitics of Death (Pluto Press, 2020).

[14] Asef Bayat, “The Politics of Fun,” chap. 6 of his book Life as Politics: How Ordinary People Change the Middle East (Stanford University Press, Second Edition, 2013). Also see Bayat, “Iran: torch of fire, politics of fun,” openDemocracy, 24 Mar. 2010.

[15] Saab and Ayoub, “The Revolutionizing Nature of the Lebanese Uprising,” p. 122.

[16] Interview with Salloukh on the podcast of the Sectarianism, Proxies and De-sectarianisation (SEPAD) project, Richardson Institute, Lancaster University, 22 Oct. 2019.

[17] Bassel F. Salloukh, “Reimagining an alternative Lebanon,” Lebanese Center for Policy Studies, 8 Nov. 2019.

[18] Bassem Mroue and Mariam Fam, “Lebanese protests test Hezbollah’s role as Shiites’ champion,” Associated Press, 18 Nov. 2019.

[19] “Hezbollah, Amal supporters attack main Beirut protest camp,” The New Arab, 29 Oct. 2019.

[20] Human Rights Watch, “Lebanon: Protect Protesters from Attacks,” 8 Nov. 2019.

[21] Joey Ayoub, “Lebanon: A Revolution against Sectarianism,” CrimethInc., 13 Nov. 2019.

[22] Nassim Badani, “Nasrallah’s Gallows Humor Comes Back to Haunt Lebanon,” Newlines Magazine, 18 June 2021.

[23] Saab and Ayoub, “The Revolutionizing Nature of the Lebanese Uprising,” p. 122.

[24] Joey Ayoub, “Hezbollah’s Resistance™ against resistance,” Discontent Issue 1 – 2021.

[25] Mersiha Gadzo, “‘All of them’: Lebanon protesters dig in after Nasrallah’s speech,” Al Jazeera, 25 Oct. 2019.

[26] “Khamenei says US stoking ‘chaos’ amid Iraq, Lebanon protests,” Al Jazeera, 30 Oct. 2019; Alaa Shahine, “Khamenei Signals Iran Opposition to Uprisings in Lebanon, Iraq,” Bloomberg, 30 Oct. 2019.

[27] “Pointing to Iraq, Lebanon, Khamenei recalls how Iran put down unrest,” Reuters, 30 Oct. 2019. On the 2017-2018 protests in Iran and the state’s brutal response to them, see Kaveh Ehsani and Arang Keshavarzian, “The Moral Economy of the Iranian Protests,” Jacobin, 11 Jan. 2018 and Amnesty International, “Iran: Stop increasingly ruthless crackdown and investigate deaths of protesters,” 4 Jan. 2018.

[28] Bassel F. Salloukh, “The Sectarian Image Reversed: The Role of Geopolitics in Hezbollah’s Domestic Politics,” in POMEPS Studies 38: Sectarianism and International Relations (Project on Middle East Political Science), Mar. 2020.

[29] Joseph Haboush, “Hezbollah and Amal change tactics and ratchet up violence amid ongoing protests,” Middle East Institute, 5 Dec. 2019.

[30] Julia Neumann, “Beirut’s ruling elite may be down, but they are not yet out: Interview with Lebanese activist Nizar Hassan,” Qantara, 11 Dec. 2019.

[31] Joseph Daher, “Hezbollah and the Lebanese Popular Movement,” IEMed Focus 162, European Institute of the Mediterranean, Feb. 2020. For a trenchant leftist critique of Hezbollah, see Daher’s book Hezbollah: The Political Economy of Lebanon’s Party of God (Pluto Press, 2016).

[32] Lena Bopp, “Beirut’s ruling class – ‘The stupidest mafia there is’: Interview with Lebanese author Elias Khoury,” Qantara (originally published in German in the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung), 5 Aug. 2020.

[33] Ayoub, “Hezbollah’s Resistance™ against resistance.”

[34] Schluwa Sama, “‘We Do Not Want These Criminals to Rule Us’: An Interview with Sami Adnan,” Jacobin, 23 Nov. 2019. Also see Rima Majed, “Understanding the October Uprisings in Iraq and Lebanon,” Global Dialogue: Magazine of the International Sociological Association, Volume 11, Issue 1 (Apr. 2021) and Nur Turkmani and Zeidon Alkinani, “From Iraq to Lebanon and back: the people want the fall of the regime,” openDemocracy, 7 Nov. 2019.

[35] “The emergence of the 2019 wave of the uprisings in Algeria, Sudan, Lebanon and Iraq showed that the Arab Spring did not die,” Asef Bayat observes. “It continued in other countries in the region with somewhat similar repertoires of collective action.” (Quoted in Hashem Osseiran, “‘The Arab Spring did not die’: A second wave of Mideast protests,” AFP, 29 Nov. 2020.) Also on this point, see Jillian Schwedler, “Thinking Critically About Regional Uprisings,” Middle East Report (MERIP) 292/3 (Fall/Winter 2019) and “The Arab Spring, a Decade Later” (interview with Gilbert Achcar, conducted by Jeff Goodwin), Catalyst Vol 4 No 3 (Fall 2020).

[36] Erica Chenoweth, Sirianne Dahlum, Sooyeon Kang, Zoe Marks, Christopher Wiley Shay and Tore Wig, “This may be the largest wave of nonviolent mass movements in world history. What comes next?” Monkey Cage (Washington Post), 16 Nov. 2019. The globality of the 2019-2020 protests is also examined in “The Global Wave of Mass Protests,” a panel discussion hosted by the Center for International and Area Studies at Northwestern University on 20 Jan. 2020.

[37] Ranj Alaaldin, “The irresistible resiliency of Iraq’s protesters,” Brookings Institution, 31 Jan. 2020.

[38] Zahra Ali, “Iraqis Demand a Country,” Middle East Report (MERIP) 292/3 (Fall/Winter 2019).

[39] Omar Sirri, “Revolutionary Protests Spread Across Central and Southern Iraq and Are Ongoing,” Jadaliyya, 26 Oct. 2019.

[40] Chantal Berman, Killian Clarke, and Rima Majed, “Patterns of Mobilization and Repression in Iraq’s Tishreen Uprising,” POMEPS Studies 42: MENA’s Frozen Conflicts (Project on Middle East Political Science), Nov. 2020.

[41] On those earlier protests, see Ali Issa, Against All Odds: Voices of Popular Struggle in Iraq (Tadween Publishing, 2015); Renad Mansour, “Protests Reveal Iraq’s New Fault Line: The People vs. the Ruling Class,” World Politics Review, 20 July 2018; and Zahra Ali, “From Recognition to Redistribution? Protest Movements in Iraq in the Age of ‘New Civil Society,’” Journal of Intervention and Statebuilding (2021).

[42] Fanar Haddad, “Iraq protests: There is no going back to the status quo ante,” Middle East Eye, 6 Nov. 2019.

[43] Berman, Clarke, and Majed, “Patterns of Mobilization and Repression in Iraq’s Tishreen Uprising.”

[44] Zeidon Alkinani, “Iraq’s October uprising: Historical context, triggers, discourse, challenges and possibilities,” in Saab (ed.), A Region in Revolt, p. 87.

[45] Fanar Haddad, “Hip hop, poetry and Shia iconography: How Tahrir Square gave birth to a new Iraq,” Middle East Eye, 9 Dec. 2019 (emphasis mine).

[46] Alkinani, “Iraq’s October uprising,” p. 93. Also see Arwa Ibrahim, “Muhasasa, the political system reviled by Iraqi protesters,” Al Jazeera, 4 Dec. 2019.

[47] Haddad, “Iraq protests: There is no going back to the status quo ante.”

[48] Zahra Ali and Safaa Khalaf, “In Iraq, demonstrators demand change — and the government fights back,” Monkey Cage (Washington Post), 9 Oct. 2019.

[49] Haddad, “Hip hop, poetry and Shia iconography.”

[50] Sama, “‘We Do Not Want These Criminals to Rule Us’.”

[51] Haddad, “Hip hop, poetry and Shia iconography.”

[52] Alkinani, “Iraq’s October uprising,” p. 100.

[53] Taif Alkhudary, “‘No to America…No to Iran’: Iraq’s Protest Movement in the Shadow of Geopolitics,” LSE Middle East Centre Blog, 20 Jan. 2020.

[54] Berman, Clarke, and Majed, “Patterns of Mobilization and Repression in Iraq’s Tishreen Uprising.”

[55] Quoted in Haddad, “Iraq protests: There is no going back to the status quo ante”. On recent shifts in Iran’s coordination of Iraq’s militias, see John Davison and Ahmed Rasheed, “Exclusive: In tactical shift, Iran grows new, loyal elite from among Iraqi militias,” Reuters, 21 May 2021; and “IntelBrief: Iran-Backed Militias Continue to Roil Iraq,” Soufan Center, 7 June 2021. Also see the investigation by James Risen, Tim Arango, Farnaz Fassihi, Murtaza Hussain, and Ronen Bergman, “A Spy Complex Revealed: Leaked Iranian Intelligence Reports Expose Tehran’s Vast Web of Influence in Iraq,” The Intercept (published in partnership with the New York Times), 17 Nov. 2019.

[56] Ali and Khalaf, “In Iraq, demonstrators demand change — and the government fights back.” Amnesty International was reporting in January 2020 that the death toll had exceeded 600 and that “[t]housands of Iraqis have been unlawfully killed, injured or arbitrarily detained over the past four months.” See “Iraq: Protest death toll surges as security forces resume brutal repression,” 23 Jan. 2020.

[57] Amnesty International, “Iraq: Eyewitness describes ‘street filled with blood’ as at least 25 protesters killed in security force onslaught,” 28 Nov. 2019.

[58] Amnesty International, “Iraq: Protest death toll surges as security forces resume brutal repression.”

[59] See Amnesty International, “Iraq: End ‘campaign of terror’ targeting protesters,”13 Dec. 2019; Iraq’s Assassins, PBS Frontline documentary produced by Ramita Navai and Mais al-Bayaa, Season 2021: Episode 11, 9 Feb. 2021; Sune Haugbolle, Henrik Andersen, “Political Assassinations and the Revolutionary Impasse in Lebanon and Iraq,” Middle East Report (MERIP), 11 May 2021; Nabil Salih, “Iraq: assassinations, repression, and the struggles of daily life,” openDemocracy, 12 May 2021; and Thanassis Cambanis, “Iraq’s Militias Continue Their Deadly Campaign Against Dissent,” World Politics Review, 7 June 2021.

[60] Ali and Khalaf, “In Iraq, demonstrators demand change — and the government fights back.”

[61] Haddad, “Iraq protests: There is no going back to the status quo ante”. Also see “More Iraqi students join anti-government protests despite deadly crackdown,” The New Arab, 28 Oct. 2019.

[62] Berman, Clarke, and Majed, “Patterns of Mobilization and Repression in Iraq’s Tishreen Uprising.”

[63] “Exclusive: Iran-backed militias deployed snipers in Iraq protests – sources,” Reuters, 16 Oct. 2019.

[64] Zeidon Alkinani, “Iran and Muqtada al-Sadr’s alliance against the revolution in Iraq,” openDemocracy, 10 Feb. 2020.

[65] Zahra Ali, “Iraqis Demand a Country” (emphasis mine).

[66] “Exclusive: Iran intervenes to prevent ousting of Iraqi prime minister – sources,” Reuters, 31 Oct. 2019.

[67] Qassim Abdul-Zahra and Joseph Krauss, “Protests in Iraq reveal a long-simmering anger at Iran,” Associated Press, 6 Nov. 2019.

[68] Alissa J. Rubin, “Iraqis Rise Against a Reviled Occupier: Iran,” New York Times, 4 Nov. 2019.

[69] Alkinani, “Iraq’s October uprising,” p. 94.

[70] Qassim Abdul-Zahra and Joseph Krauss, “Iraqi protesters attack Iran consulate in Karbala,” Associated Press, 3 Nov. 2019; “Iraq unrest: Protesters set fire to Iranian consulate in Najaf,” BBC, 28 Nov. 2019.

[71] Sama, “‘We Do Not Want These Criminals to Rule Us’.”

[72] Gilbert Achcar, “Iraqis want both countries out,” Le Monde diplomatique (English edition), Feb. 2020. Also see Alkhudary, “’No to America…No to Iran’.”

[73] Haddad, “Hip hop, poetry and Shia iconography.”

[74] Qassim Abdul-Zahra and Joseph Krauss, “Protests in Iraq and Lebanon pose a challenge to Iran,” Associated Press, 30 Oct. 2019.

[75] See Zeina Karam, “‘We are hungry’: Lebanese protest worsening economic crisis,” Associated Press, 16 Mar. 2021 and “Iraqi protesters take to streets, decry targeted killings,” The Independent, 25 May 2021.

[76] See the open letter “Erasing people through disinformation: Syria and the ‘anti-imperialism’ of fools,” Al-Jumhuriya, 27 Mar. 2021.

[77] See, for example: Afra Jalabi, “Anxiously Anticipating a New Dawn: Voices of Syrian Activists,” in Nader Hashemi and Danny Postel (eds.), The Syria Dilemma (MIT Press, 2013); Tamara al-Om, “Don’t ignore Syria’s nonviolent movement,” The Guardian, 7 June 2014; Malu Halasa, Nawara Mahfoud, and Zaher Omareen (eds.), Syria Speaks: Art and Culture from the Frontline (Saqi Books, 2014); “Syria’s good guys — Inside a forgotten revolution,” special issue of the New Internationalist (Sept. 2015, Issue 485); Robin Yassin-Kassab and Leila Al-Shami, Burning Country: Syrians in Revolution and War (Pluto Press, 2016), especially chaps. 3 (“Revolution From Below”), 4 (“The Grassroots”), and 8 (“Culture Revolutionised”); Yassin al-Haj Saleh, The Impossible Revolution: Making Sense of the Syrian Tragedy (Hurst, 2017), especially chap. 1 (“Revolution of the Common People”); Leila Al-Shami, “The Legacy of Omar Aziz: Building autonomous, self-governing communes in Syria,” Fifth Estate # 397, Winter, 2017; Estella Carpi and Andrea Glioti, “Toward an Alternative ‘Time of the Revolution’? Beyond State Contestation in the struggle for a new Syrian Everyday,” Middle East Critique Volume 27, Issue 3 (2018); Anand Gopal, “Syria’s Last Bastion of Freedom,” The New Yorker, 10 Dec. 2018; Wendy Pearlman, “Civil Action in the Syrian Conflict,” in Deborah Avant, Marie Berry, Erica Chenoweth, Rachel Epstein, Cullen Hendrix, Oliver Kaplan, and Timothy Sisk (eds.), Civil Action and the Dynamics of Violence (Oxford University Press, 2019); Wendy Pearlman, “How the Syrian uprising began and why it matters,” The Conversation, 14 Mar. 2019; Yasser Munif, The Syrian Revolution: Between the Politics of Life and the Geopolitics of Death (Pluto Press, 2020); Leila Al-Shami, “Building Alternative Futures in the Present: The Case of Syria’s Communes,” The Funambulist, Issue 34 (Mar.-Apr. 2021); Lewis Sanders IV, Birgitta Schülke-Gill, Wafaa Albadry, Julia Bayer, “Razan Zeitouneh – the missing face of Syria’s revolution,” Deutsche Welle (DW), 15 Mar. 2021; Charlotte Al-Khalili, “Rethinking the concept of revolution through the Syrian experience,” Al-Jumhuriya, 5 May 2021. Also see “The Syrian Revolution: A History from Below,” a series of webinars convened over the summer and fall of 2020.

[78] Rania Abouzeid, “The Jihad Next Door,” POLITICO, 23 June 2014 and Maria Abi-Habib, “Assad Policies Aided Rise of Islamic State Militant Group,” Wall Street Journal, 22 Aug. 2014.

[79] Arash Azizi, The Shadow Commander: Soleimani, the US, and Iran’s Global Ambitions (Oneworld, 2020), p. 215.

[80] Danny Postel, “Theaters of Coercion,” Democracy: A Journal of Ideas, Fall 2016, No. 42. On the extreme brutality of the regime’s repression in response to peaceful demonstrations in 2011, see the Human Rights Watch report “By All Means Necessary!” Individual and Command Responsibility for Crimes against Humanity in Syria, 15 Dec. 2011.

[81] Christopher Phillips, The Battle for Syria: International Rivalry in the New Middle East (Yale University Press, 2016; revised and updated edition, 2020), p.68. Also see Joby Warrick, “Iran reportedly aiding Syrian crackdown,” Washington Post, 27 May 2011 and Robert Booth, Mona Mahmood and Luke Harding, “Exclusive: secret Assad emails lift lid on life of leader’s inner circle,” The Guardian, 14 Mar. 2012.

[82] Jubin Goodarzi, “Syria: the view from Iran,” European Council on Foreign Relations (ECFR), 15 June 2013.

[83] Quoted in Roland Elliott Brown, “Syria, Iran’s ‘Strategic Province,’” IranWire, 16 July 2014.

[84] Saeed Kamali Dehghan, “Tehran supports the Arab spring … but not in Syria,” The Guardian, 18 Apr. 2011.

[85] Amin Saikal, “Iran: Aspirations and Constraints,” in Adham Saouli (ed.), Unfulfilled Aspirations: Middle Power Politics in the Middle East (Oxford University Press, 2020), p. 117.

[86] Ewan Stein, International Relations in the Middle East: Hegemonic Strategies and Regional Order (Cambridge University Press, 2021), p. 196. On this point, also see Edward Wastnidge, “Iran’s Own ‘War on Terror’: Iranian Foreign Policy Towards Syria and Iraq During the Rouhani Era,” in Luciano Zaccara (ed.), Foreign Policy of Iran under President Hassan Rouhani’s First Term (2013–2017) (Palgrave Macmillan, 2020), pp. 107-129.

[87] See Yassin-Kassab and Al-Shami, Burning Country, chaps. 5 (“Militarisation and Liberation”) and 6 (“Scorched Earth: The Rise of the Islamisms”); Charles R. Lister, The Syrian Jihad: The Evolution of an Insurgency, revised and updated edition (Hurst, 2017); and Paulo Gabriel Hilu Pinto, “The Shattered Nation: The Sectarianization of the Syrian Conflict,” in Hashemi and Postel (eds.), Sectarianization.

[88] See the Human Rights Watch report Torture Archipelago: Arbitrary Arrests, Torture, and Enforced Disappearances in Syria’s Underground Prisons since March 2011, 3 July 2012; Ian Black, “Syrian regime document trove shows evidence of ‘industrial scale’ killing of detainees,” The Guardian, 21 Jan. 2014; Budour Hassan, “Syria’s Desaparecidos,” The New Inquiry, 18 Nov. 2016; and the 2017 documentary film Syria’s Disappeared, directed by Sara Afshar and co-produced by Afshar and Nicola Cutcher (available on Amazon Prime Video in the US and UK).

[89] See Salwa Ismail, The Rule of Violence: Subjectivity, Memory and Government in Syria (Cambridge University Press, 2018), especially chaps. 1 (“Violence as a Modality of Government in Syria”) and 2 (“Authoritarian Government, the Shadow State and Political Subjectivities”); and Yassin al-Haj Saleh, The Impossible Revolution, especially chaps. 2 (“The Shabiha and their State”) and 5 (“The Roots of Syrian Fascism”).

[90] Azizi, The Shadow Commander, p. 207.

[91] Azizi, The Shadow Commander, p. 213.

[92] Borzou Daragahi, “Iran’s revolutionary bluster masks its role as oppressor in the Middle East,” Iran Source (Atlantic Council), 5 Nov. 2019.

[93] Stein, International Relations in the Middle East, p. 195 (emphasis mine).

[94] Rami G. Khouri, “The battle of ‘resistance’ vs ‘revolution’ in the Middle East,” Al Jazeera, 14 Jan. 2020. Also see Khouri, The Decade of Defiance & Resistance: Reflections on Arab Revolutionary Uprisings and Responses from 2010 – 2020, a report published by the Soufan Center, May 25, 2021.

[95] Saikal, “Iran: Aspirations and Constraints,” p. 124.

[96] Daragahi, “Iran’s revolutionary bluster masks its role as oppressor in the Middle East.”

[97] Wastnidge, “Iran’s Own ‘War on Terror,’” p. 111.

[98] Christopher Davidson, Shadow Wars: The Secret Struggle for the Middle East (Oneworld, 2016), p. 514 (emphasis mine).

[99] Ben Hubbard, Farnaz Fassihi, and Jane Arraf, “Fierce Foes, Iran and Saudi Arabia Secretly Explore Defusing Tensions,” New York Times, 1 May 2021; Ali Harb, “Saudi Arabia-Iran rapprochement: What is driving push for diplomacy?” Middle East Eye, 5 May 2021.

Despite recent organizing gains among some contingent faculty members, the adjunctification of higher education has left hundreds of thousands of college and university teachers with low pay, spotty benefit coverage, and little job security. As former adjuncts Joe Berry and Helena Worthen report in their new book,

Despite recent organizing gains among some contingent faculty members, the adjunctification of higher education has left hundreds of thousands of college and university teachers with low pay, spotty benefit coverage, and little job security. As former adjuncts Joe Berry and Helena Worthen report in their new book,

This article was written for L’Anticapitaliste, the weekly newspaper of the New Anticapitalist Party (NPA) of France.

This article was written for L’Anticapitaliste, the weekly newspaper of the New Anticapitalist Party (NPA) of France.

July 11, 2021

July 11, 2021

Yesterday, July 11, 2021, Cubans in several cities took to the streets to protest lack of health care, lack of food, and to demand freedom. Where should socialists stand on these protests and the Cuban government?

Yesterday, July 11, 2021, Cubans in several cities took to the streets to protest lack of health care, lack of food, and to demand freedom. Where should socialists stand on these protests and the Cuban government?

This article was written for L’Anticapitaliste, the weekly newspaper of the New Anticapitalist Party (NPA) of France.

This article was written for L’Anticapitaliste, the weekly newspaper of the New Anticapitalist Party (NPA) of France.

Professional politicians are a relatively recent historical phenomenon and their lies are to a great extent a response to social structural imperatives that did not exist in precapitalist societies. Surely liberal capitalist democracy did not invent political lies. Neither did capitalism invent exploitation and oppression. However, as in the case of exploitation and oppression, political lies acquired new content and form under liberal democratic capitalism.

Professional politicians are a relatively recent historical phenomenon and their lies are to a great extent a response to social structural imperatives that did not exist in precapitalist societies. Surely liberal capitalist democracy did not invent political lies. Neither did capitalism invent exploitation and oppression. However, as in the case of exploitation and oppression, political lies acquired new content and form under liberal democratic capitalism.

During the pandemic, hate crimes against Asian Americans have

During the pandemic, hate crimes against Asian Americans have

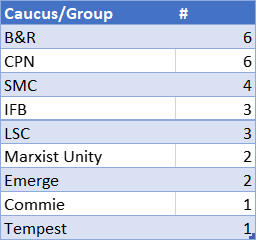

Here we are again: DSA convention time. As I did

Here we are again: DSA convention time. As I did

OPEN LETTER BY

OPEN LETTER BY

As I write, the government of the Hong Kong Special Autonomous Region (SAR) has banned the annual candlelight vigil to remember the 1989 democracy movement in China for the second consecutive year. Every June 4th since 1990 a vigil has been held in Hong Kong, and each year hundreds of thousands of people have poured into the city’s Victoria Park to remember the victims of the bloody crackdown in Tiananmen Square and keep alive the hope for a democratic China.

As I write, the government of the Hong Kong Special Autonomous Region (SAR) has banned the annual candlelight vigil to remember the 1989 democracy movement in China for the second consecutive year. Every June 4th since 1990 a vigil has been held in Hong Kong, and each year hundreds of thousands of people have poured into the city’s Victoria Park to remember the victims of the bloody crackdown in Tiananmen Square and keep alive the hope for a democratic China.

This article was written for L’Anticapitaliste, the weekly newspaper of the New Anticapitalist Party (NPA) of France.

This article was written for L’Anticapitaliste, the weekly newspaper of the New Anticapitalist Party (NPA) of France.