DSA Convention Primer: 2021 Edition

Here we are again: DSA convention time. As I did in 2019, I’ll go through the basics of the convention and then give an overview of the proposals and items for consideration.

Here we are again: DSA convention time. As I did in 2019, I’ll go through the basics of the convention and then give an overview of the proposals and items for consideration.

Every two years, the Democratic Socialists of America convene for a national convention. The convention will elect a new sixteen (16) person leadership, the National Political Committee (NPC). Delegates will also vote on resolutions, which form new campaigns or working groups and commit DSA to a projects, policies, or courses of action; bylaw and constitution changes, which are the rules and structure for how DSA works; and for the first time this year delegates will vote on a national platform, stating DSA’s positions on a range of topics in the short, medium, and long-term. NPC elections are for the leadership that will direct DSA for the next two years, resolutions are commitments to do something, bylaw changes are about changing how DSA works internally, and the platform lays out our positions.

Convention Logistics

DSA National allocated 1300 delegates for the 2021 Convention, at a ratio of 1 delegate per 70 members. (Last convention was approximately 1100 delegates at a ratio of 1 per 50.) The convention will be held online in light of COVID-19, spread out over roughly eight days – most voting is not scheduled to begin until Thursday, August 5th.

This year, thirty-eight (38) resolutions and eight (8) bylaw changes have been submitted in the preconvention period. This is down significantly from 2019, where there were eighty-five (85) resolutions and thirty-three (33) submitted bylaw changes. (When you consider that the organization has nearly doubled, that’s even more stark.) Any DSA member (you don’t have to be a delegate) can try to amend the submitted proposals through Tuesday, June 15th, provided they have collected 100 signatures from DSA members in good standing. Likewise, amendments to the draft DSA platform can be submitted through Tuesday, July 15th with 250 signatures.

This year’s rules stipulate that the convention will only debate twenty (20) proposals, at least five (5) must be constitution/bylaw amendments, not including items in a “consent agenda” . Elected delegates will have to pick which of the forty-eight proposals submitted will be heard and voted on. A priority poll will be emailed to all delegates in advance of the convention (by July 19th) to rank and vote to determine what should be heard at the convention. The poll is also used to construct a “consent agenda”* – proposals that are popular enough among delegates that rather than individually debate them, they’re rolled together to be voted on as a package.

Report on the state of DSA

In the 164-page compendium of proposals, the first 11 pages begin with an appeal from the staff. In so many words, we’re broke. “Our annual budget currently has a projected deficit of $7,000 for 2021. This means we have <-$7,000> to spend on new work. It would thus be impossible to enact any new proposals without cutting other work!…After the 2019 convention, the NPC had to make hard decisions between cutting existing staff work and reallocating that time, or not carrying out some resolutions even though they passed in 2019.” This makes three years in a row that DSA National has budgeted for a deficit.

DSA has grown from 148 to 240 local chapters and 130 YDSA chapters. Staff has expanded from sixteen (16) full-time and one part-time staff at this point in 2019, to twenty-nine (29) full-time and two (2) part-time staff now in 2021. Seven of these full-time staff are considered field organizers: two for YDSA (which makes them responsible for 65 chapters each) and five regional DSA organizers (supporting 48 chapters each on average). Field organizers are also attached to specific areas of work (Labor, Green New Deal, etc.)

Players in the game

Since the first convention of the “new” DSA in 2017, caucusing has played an important role in the organization. Caucuses generally have two purposes: 1) getting together with others who have similar politics or objectives; 2) organizing to win your proposals and preferred candidates to leadership positions.

There’s nothing that makes any grouping an “official” caucus in DSA – the bylaws don’t recognize caucuses as part of the structure of the organization, you don’t register anywhere, and you get no official privileges or expectations for being in a caucus. Caucus is as caucus does: if you’re meeting with a group your comrades to influence the organization, you’re caucusing.

Every caucus has different internal culture, politics, and structure. The practice has proliferated in DSA because caucusing helps those who aspire to leadership to have a structure that can whip votes, share member or officials’ contacts, and have access to information about how DSA works and how to get what you want. For the average member, DSA can be a bureaucratic maze and there’s too much information to figure out how to get involved or get something started, so caucuses have an advantage.

2021 looks somewhat different because there are still a few major national caucuses, but there’s been a kind of fracturing where now there are many smaller groupings and local caucuses that make it a little harder to explain easily.

- Bread and Roses (B&R): Probably the largest national caucus in DSA, B&R focuses on elections and labor activism. Their politics are distinguished by their takes on a “democratic road to socialism” (rather than revolution), dirty break theory, and a labor politics heavily influenced by Jane McAlevey.

- Socialist Majority (SMC): A second large caucus, SMC prizes “coalition work” and turning DSA into a genuinely multi-racial organization. Politically, they tend to be on the organization’s center-right as a more outright reformist grouping that historically argues for electing even mainstream Democrats.

- Collective Power Network (CPN): What would have been the third major national caucus, CPN recently succumbed to bitter internal conflict that crashed their organization. CPN’s signature positions are in favor of an electoral “party surrogate”, disciplined campaigns, and support of the union officialdom (explicitly against a “rank and file strategy”). They largely draw on the Popular Front-era Communist Party as inspiration.

- Libertarian Socialist Caucus (LSC): DSA’s libertarian socialists (including syndicalists, wobblies council communists, anarchists, cooperativists, and municipalists). They generally favor decentralization, localism, mutual aid, and direct action.

- Reform & Revolution (R&R): A right-split from Socialist Alternative, R&R joined DSA 2020 in order to more openly support Sanders and efforts at a dirty break. They tend to prioritize elections.

- Class Unity Caucus (CUC): Hard anti-identity politics, prioritizes a working class party.

- Communist Caucus (Commie caucus): National grouping of communists interested in base-building and movements.

- Marxist Unity: A group that runs the publication Cosmonaut, influenced by Kautsky and pre-war social democracy.

- Internationalism from Below: A network of anti-campist internationalists.

- Tempest: A revolutionary socialist collective, emphasizing struggle from below. Many are former members of the International Socialist Organization (ISO) or Solidarity.

- Local communist caucuses: Emerge (New York City): Red Caucus (Portland OR): Red Star (San Francisco).

Overview of Proposals

Of the thirty-eight (38) proposals, we can categorize them to see both what the priorities are and the political dynamics of the factions. If every proposal was passed with the pricing estimated by DSA national, it would cost $6.2 million, and add an additional 36 staff.

Just by the numbers, the hottest topics in DSA in 2021 are organizational/financial issues, electoral politics, and internationalism – together those make up 2/3’s of the submitted resolutions. This is similar to the interests in 2019, with some notable exceptions. Last convention, labor was a primary point of contention with seven (7) competing resolutions; this year there is only one labor proposal, authored by the sitting Democratic Socialist Labor Commission (DSLC) as a joint effort of B&R, CPN, and SMC. There’s an absence of resolutions on feminism/gender this year, and no proposals concerning fascism or the far right.

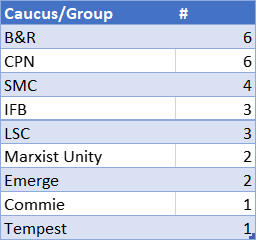

Internal caucuses or groups account for 27 of the 38 resolutions (71%), compared to 40% in 2019. B&R and CPN authored the most resolutions (6 each), followed by SMC. (Some resolutions are authored jointly by multiple caucuses, so the table numbers add up to more than 27.) Resolutions authored by national working groups account for most of the rest of the resolutions, so less than 10% of resolutions appear to be authored by unaffiliated rank and file members.

Only eight (8) constitution/bylaw changes were submitted in 2021, compared to thirty-three (33) in 2019. All of these are attached to caucuses or groups. These can be grouped into three categories: process issues (C1, C3, C7), structure changes (C2, C6), and transparency/accountability (C4, C5, C8).

Looking at the Proposals

Given how few proposals there are, and the limit on how many will even be heard, there’s not a whole lot to choose from. There are only four (4) so-called priority resolutions to focus on an area of work (electoral, labor, medicare for all, green new deal), which are the same as the previous two conventions. Proposals don’t offer choices of strategy for DSA, which is particularly striking considering that last year’s anti-racist protests after police murdered George Floyd brought millions into the streets in the largest demonstrations in US history.

There are only a few areas of contention: elections, internationalism, and organizational functioning and democracy.

Elections

The electoral resolutions come down to a basic question: keep doing the same thing, or time to change? They deal with what’s happened with DSA’s electoral work since 2019. How do members evaluate the “socialist slate” in New York, for instance? In Chicago, four city alders (including one backed by DSA) flipped and voted for Lori Lightfoot’s austerity budget, allowing it to pass. How does this inform DSA’s relationship to politicians we help elect?

Resolution #8 (“Toward a Mass Party in the United States”) is written by the National Electoral Committee (NEC), comprised largely of members from B&R and SMC, is the status quo: continue running as Democrats using the primary system, with no stipulations. The resolves are largely abstract (“Resolved that DSA commits to a strategy of using elections to win reforms that materially advance the interests of the working class and aim to democratize our economy and society”), but there isn’t a lot of meat to chew on in terms of defined positions or actions. The largest shift in in focusing on state legislatures.

Reform and Revolution (R&R) has three resolutions (R9, R10, R11) that generally agree with the existing practice but have specific ambitions: run ten independent partisan election campaigns in 2022 (R9); be open in distinguishing socialist candidates running as Democrats by expressly criticizing the Democratic Party when they run (R10); and take concrete steps towards establishing a “Democratic Socialist Party” in 2022 (R11).

Marxist Unity (MU) has two resolutions that focus more on the relationship between DSA and candidates the organization supports. “Tribunes of the People” (R6) proposes that candidates who want a DSA National endorsement must be a member of DSA, fight for DSA’s platform, meet with DSA leadership, and caucus and block together where there are concentrations in a legislature. MU’s second resolution (R7) proposes DSA run its own slate of candidates for the US House of Representatives.

Tempest (note: I’m a member and author of this resolution) proposed R38 (“A Socialist Horizon”), which takes language from 2019’s “Class Struggle Election” resolution but expands it with some specifics. It establishes that in order for a candidate to get a National endorsement, they would have to 1) openly identify as a socialist in their messaging and materials; 2) pledge to refuse to vote for any criminal or immigration law enforcement; 3) refuse support from fossil fuel, real estate, and law enforcement, among others; and 4) they have to get the endorsement from the DSA local chapter(s) they’d be representing before they could get a national endorsement. It adds teeth by saying that if they go back on their pledges, DSA would censure them and reserves the right to end their membership.

Internationalism

There are six (6) internationalist resolutions, and on the surface its not entirely clear what they mean. These are actually from two opposed groups on DSA’s International Committee (IC), disputing both policy and organizational form of the IC. In 2019, the IC was restructured.** The National Political Committee (NPC) appointed the leadership of the new IC, and membership to the IC was taken by application and selected by this appointed leadership.

The IC leadership politically aligned themselves with a politics of “anti-imperialist” geopolitical camps (such as the Latin American Pink Tide governments, Cuba, and even the Chinese state), while there were also volunteer members with an “anti-campist” or “international class solidarity” politics that oppose imperialism but do not specifically align with the governments or regimes of any country. The language here will be contentious, and either side view the other’s descriptions of each other pejoratively. (“Campists” call themselves “anti-imperialists” and call their opponents the “third camp” or hurl blanket accusations of racism; “anti-campists” call themselves “internationalists” and frequently accuse the other side of being Stalinists.)

Collective Power Network, Emerge, and Red Star tend to place themselves in the campist/anti-imperialist group; Bread & Roses, Internationalism from Below, and Tempest in the anti-campist/international solidarity group. Many DSA members aren’t particularly well versed in international politics, and international questions tend to get siloed off towards those most passionate about them. The difficulty for the convention will be going beyond surface attitudes (“They say they’re socialists, they must be good”) and straw man attacks.

You can already see how this is messy, but it is a central question of this convention: what is DSA’s international stance? R14 (“Committing to International Socialist Solidarity”) is written by the IC leadership (campist) – it specifies that DSA will 1) formalize relationships with “mass parties in other countries” (such as the MAS in Bolivia, the PSUV in Venezuela, and the PT in Brazil); 2) apply for membership in the São Paulo Forum (launched by the PT in Brazil); and 3) create exchange programs with said international parties. R18 (“International Committee and Mass Organizing”) is written by Emerge members also on the IC leadership, and generally focuses on the structure of the IC.

Internationalism from Below advanced three resolutions as anti-campists (R15, R16, and R17). R15 and R16 both concern the internal operation of the IC – they propose that the regional subcommittees (Africa, Latin America, Europe, Asia, etc.) would 1) elect their own co-chairs annually; and 2) have voting representatives on the IC Steering Committee. R17 articulates a political vision for DSA’s international work: in brief, critical support. “Critical support for left governments or other governments defending themselves from imperialism means conditional support, which implies being able to evaluate and analyze the dynamics on the ground.”

Organization

The last major area being debated in 2021 is DSA’s organization and democracy. Some of these are fairly innocuous: do more trainings; create communications and tech policy, etc. Some are questions that were taken up at last convention but haven’t seen movement: R35 (“Spanish Translation and Bilingual Organizing”) brings up that DSA should operate in English and Spanish – this was passed in 2019 but has not been accomplished. R32 deals with Young Democratic Socialists of America (YDSA): YDSA is subservient to DSA, and its structure has been neglected. R32 seeks to give YDSA more discretion over its own operations.

Constitution/bylaw changes are a mix of big and small changes. C1, C3, and C7 are process-related: striking regional requirements for national conventions set up long before DSA grew (C1); C3 adds NPC alternates in the event of an absence or resignation; C7 makes all elections held in DSA as only by single-transferrable vote.

C8 (“Defining the Role of DSA’s National Platform”) changes the definition of membership to be more specific, so that members must agree to fight for DSA’s adopted platform (as opposed to agreement with general principles). C4 (“Electing DSA’s National Director”) makes the National Director (it’s been Maria Svart for over a decade) into an elected position with a two-year term rather than a job hired by the NPC.

C6 creates a new body in DSA National called the “National Organizing Committee” (NOC), is a kind of “senate”. A version of this proposal was made in 2019 by the same authors, who are members of SMC. The NOC would be 100 members, proportional to number of members in a region (more members, more delegates). The proposal makes the NOC able to reverse NPC decisions, approve budgets, fill NPC vacancies, and change the bylaws of DSA.

C2 (“National Referendum”) and C5 (“For a National Leadership Elected by and Accountable to DSA members”) are democratic reforms to DSA proposed by Tempest (again, I am an author). C2 creates a binding referendum, which allows members to directly vote on questions to set policy, reverse NPC decisions, set a course of action, or vote on constitution/bylaw changes in between conventions. Any member would be able to submit a referendum, and if they meet the required signatures, it would be posed to the entire membership of DSA, one-person one-vote. The closest thing DSA has had to this was an advisory poll on whether to endorse Bernie Sanders, which was non-binding. C2 gives those votes teeth, and it allows the membership to vote on changes to DSA’s structure, where right now that can only be done at convention (and no structure changes have been made since at least 2015).

C5 handles a few different issues.

- Allows NPC members to be recalled by the membership

- Establishes that NPC vacancies will be filled by election done by popular vote, rather than NPC appointment.

- All NPC votes will be roll-called (meaning every NPC member has to report how they voted on each question they take up), including online “Loomio” votes

- All votes and minutes reported within three days of approval

Together you see that there are problems in DSA’s structure and that there are various proposals on what, if anything, to do. Some proposals create more intermediary bodies, others more direct governance mechanisms. It is a political question about who runs DSA and how.

Conclusions

There’s a whole lot of information, even in a summary. What’s noticeable is that there are few choices for delegates, and so it raises the issue that even if there are delegates with distinct politics, are they going to be able to express them if there aren’t proposals? Many of the questions of the last convention seem to be settled: there’s no more debate about centralization or decentralization; no question of “the rank-and-file strategy”; no immediate political questions DSA has to pick a side on.

Elections continue to be a central question, which makes sense because of the premium DSA puts on them. Internationalism is an unexpected conflict that is particularly sharp in 2021, though I think that this is serving as a proxy for a general vision of socialism in DSA: what’s the horizon? What do our opinions of other countries’ experiences relay about how we think the struggle for socialism will unfold?

A last, major question is about democracy. It should be a major red flag that the number of proposals has sunk compared to previous years, especially when we weight them by the size of the organization. A small minority of proposals are coming from rank-and-file members. Yes, as DSA grows it makes sense that more members will be plugged into caucuses or national working groups, but to have fallen to less than 10% of proposals is drastic. This suggests that many DSA members have withdrawn or simply stopped caring about what happens with national.

There’s good reason for this: in 2019, many proposals that “won” never ended up going anywhere. A priority campaign over immigration received overwhelming support from delegates, but never materialized. Spanish translation never happened. The anti-fascist working group only kind of got started at the beginning of 2021. The Democratic Socialist Labor Commission has been silent, and the two most visible labor efforts, the Emergency Workplace Organizing Committee (EWOC) and the PRO Act, came from the NPC rather than the DSA’s labor body.

This teaches members that the convention and the national organization doesn’t matter and isn’t worth the effort. Staff and the NPC may say they operated under constraints and couldn’t allocate staff to the things the convention mandated, but this falls flat when they invent campaigns while they ignore convention directives. For that reason, democracy in the organization becomes a central political question. If you don’t believe the organization will follow the will of the membership, you give up on organization.

Notes

* Convention rules originally stipulated that this would be ten resolutions and ten bylaw/constitution amendments. Only eight bylaw/constitution amendments were submitted, so they changed the interpretation to be a total of twenty with at least five bylaw changes. Per inquiry to convention committee, 6/9/21.

** The new IC followed a convention resolution. The particulars of how that was passed is a little shady, since it was bundled together with resolutions on Boycott, Divest, and Sanction, Decolonization, and Cuba work.