Oksana Dutchak is a researcher based in Ukraine and an activist of E.A.S.T. – Essential Autonomous Struggles Transnational. She tells about the current ever-changing situation in Ukraine and local attempts of self-organization to cope with the war. The question of how to create a transnational politics of peace has no easy answer. Continuing to mobilize and communicate across the borders is crucial but it should go hand in hand with radically rethinking the transnational itself.

Oksana Dutchak is a researcher based in Ukraine and an activist of E.A.S.T. – Essential Autonomous Struggles Transnational. She tells about the current ever-changing situation in Ukraine and local attempts of self-organization to cope with the war. The question of how to create a transnational politics of peace has no easy answer. Continuing to mobilize and communicate across the borders is crucial but it should go hand in hand with radically rethinking the transnational itself.

What is the situation in Ukraine right now and what has been the reaction of the local population to the outbreak of the war?

The situation is very complicated. During the first days it seemed that Russian military forces were trying not to target civilians. They were trying to destroy the military infrastructure of the country supposing that the government and society would just give up but it didn’t work.

I’m wondering how stupid the intelligence was: their calculation was a total mistake.

It didn’t work because the army started to act and people on the ground started to act.

It gives some hope, but it changed their tactic definitely dramatically.

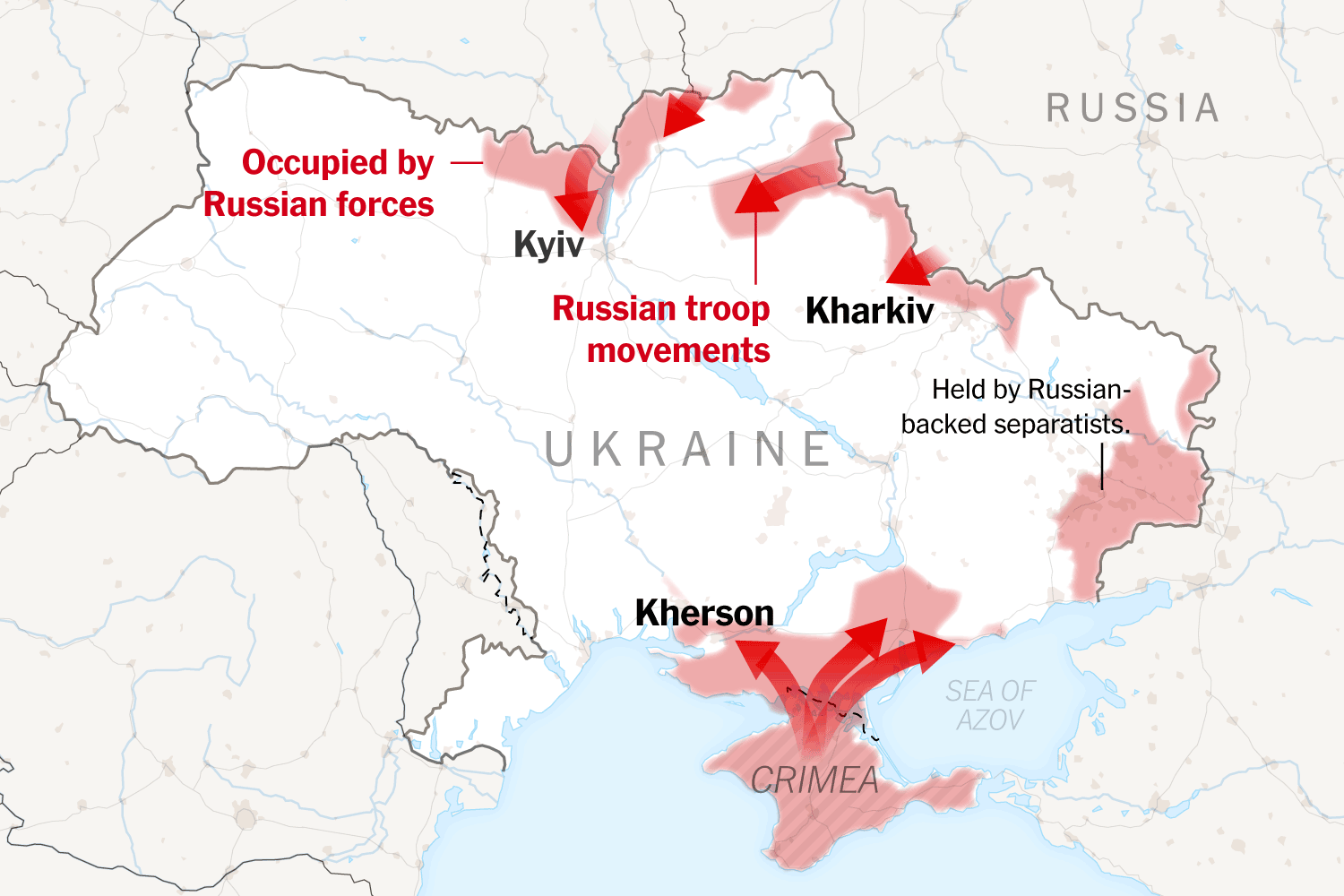

Now they are attacking civilians. Today [March 2nd 2022] the city of Kharkiv was heavily bombed, targeting specifically the residential districts, and the city center. We don’t know how it will go on from now.

This change in tactics means both that they feel like they made a huge mistake at the beginning with this calculation, and that it is very dangerous for civilians.

As for civil population, many Western leftists now blame NATO, but nobody did more for local population to support NATO and the idea of joining NATO than Russia is doing now. Just now there is a poll, according to which a record of 76% support the idea, mostly because of skyrocketing figures in usually oppositional (to NATO) Eastern and Southern Region. When all these warnings were issued by the US military and officials, that Russia was going to attack but not so many people believed that. I didn’t believe that until the last moment. Now it looks that Russia has been actively preparing full scale invasion at least for some months.

The population got very anti-Russian now. By trying to make Ukraine the country under their total influence, they are doing the opposite thing because the majority of people are now very against Russia.

There are people who are not radically anti-Russia. But it is hard when you see what is happening, the bombing in Kharkiv – which is one of the biggest cities in Ukraine and a predominantly Russian-speaking city. The level of hate is very high now. It is explainable. It is hard in these circumstances to perceive Russia differently.

Ukrainian left people were talking about it for a while already but usually it was in vain and nobody paid attention. Now we see how Russia is trying to restore its imperial power with very bad outcomes for us, Russians, world’s stability and all that.

I have friends who stayed in cities under attack and relatives who could not get out or did not want to. Many of them are preparing for guerrilla. That’s also a huge miscalculation on the side of the Russian government because – I don’t know if they really believed it or not – their message was: all people will greet us on the ground. Instead, we see footage of unarmed civilians just stopping tanks on their way. It is also probably one of the reasons why they changed tactics and they decided to start the air strikes on civilians to demoralize them, because you cannot stop airplanes by blocking the road without arms.

There are also cases when people attack tanks with Molotov cocktails etc. Kyiv is preparing for guerrilla and many other cities do so too. Even if their calculation would somehow work out and they would be able to install the puppet government here, the occupational government won’t last long because it would be a total spiral of escalation, involving civilian population. Not all people are doing that, but it is hard not to do it when such things are happening. I think that in many settlements people would try to resist also peacefully. If the airstrikes destroy towns, it will be hard to resist in any form.

The outbreak of a full-blown war in Ukraine has been prepared by weeks of war rhetoric on both the US and Russian side. How do feminist and workers organizations in Ukraine position themselves in the ongoing situation?

Different organizations reacted differently. People are trying to volunteer and organize some support for civilians. There is a lot of self-organization going underground to support evacuation of people, to help them reaching a safe place, but also to support people who are left in the cities, who cannot go or don’t want to go, but they are lacking medicine or food. Also some grassroots initiatives are preparing for guerrilla in organized but also in unorganized ways.

Many use their external connections with people abroad to help those who are crossing the border, because they need transfer, they need a place to stay in Poland, Romania, Moldova. This kind of networking is also intensively involved. This is what anarchists, feminists and left organizations are also doing. There is a lot of self-organization connected both to helping civilians and preparing for the upcoming invasions in the city.

We are seeing people stuck at the borders and often discriminated because of the color of their skin. Do you have any news on that side?

This problem exists – don’t know how systematic it may be though. Human rights activists are trying to rise this question and speak publicly about it. And just recently there was official reaction from the government with explicit statement that there must be no discrimination and with separate online form for foreign students distributed – to assist their route across the border.

I see how differently Europe reacts. Poland opened the borders for Ukrainian refugees – it was one of the first countries to do so. Compare it to their reaction when there was the Polish-Belarusian border crisis. I see it totally and perceive it from a critical perspective. This is racism, of course. It is not about these countries being too good to Ukrainians. It is about them being bad to other people. It tells a lot about racism and about how different countries are perceived.

Do you have any news from the border? Are there people you know who have been able to cross the borders?

There are huge, huge rows of people, crossing on cars and by foot and the situation is hard. A friend of mine was fleeing the country. She spent two days on the border. She and her three kids. Luckily, they have already crossed to the other side. The problem is that the amount of people who are trying to leave is huge and volunteers on both sides of the borders are trying to help somehow in a humanitarian way because people do not have enough clothes and the nights are cold. So they are trying to put them somewhere or at least try to help them. From the Polish side, Moldovan side, people are trying to organize transfers for Ukrainians, for free mostly, and take them to places where to stay, or to take them to cities where they have relatives.

Is it possible to build an opposition against this war without falling into the alternative between NATO and Russia? Is it possible to build a women’s, migrants’ and workers’ transnational initiative that escapes nationalistic logics and the geopolitical perspective?

I had discussions with leftist people from other countries and I am sometimes surprised of how they are afraid of putting too little blame on NATO and they are trying to put in every phrase that ‘It is also NATO to blame’. Sure, NATO can be blamed to some point in time, but when the bombs start falling from the sky – only Russia can be blamed for bombing. From here on the ground the situation looks differently because we see how Russian government behaves. They are not willing to give up their plans. We can hardly say let’s keep Russia and NATO away from here, because it is only Russia who invaded Ukraine. Because it is not NATO who is bombing the cities, it is very obvious here.

You cannot say: Let’s not take sides. You cannot avoid taking sides, especially when you are here. I don’t advise people from Western or Eastern European countries left to say that we are not taking sides. Not taking sides here would mean washing their hands.

A friend told me that it is also NATO’s guilt and after everything will be over we will have a very nationalism, xenophobic country and other problems. So I answered him: Sure, we probably will, but I will think about it later when there will be is no shelling of cities and when there will be no Russian army here. Now we cannot solve these problems. We can talk about them, but we cannot ignore the elephant in the room.

Some leftist people are saying that the way out is to negotiate and agree on the neutrality of Ukraine. It is hard for me to support this point at the moment. This position is a little bit colonial: denying also the sovereignty of a country. It is up to the people in the country to decide what they want to do and for them being able to decide, there should be no war. As I’ve said, this war made decisions for many Ukrainians. People say there is always a choice. But most Ukrainians don’t see a choice now.

We are not denying our agency. Some people on the Left – in Western Left – are denying our agency, telling us what Ukrainians should do.

It sounds very nice to say that Ukraine should not take any side, should not be in any block, should keep a neutral status. But we see from history that a neutral status is reserved for strong states, for rich states, for states who can defend themselves. Ukraine could not defend itself from the attack and now it is trying to do so but I don’t know how long we can continue.

After 2014’s Crimean annexation talking about a neutrality status for Ukraine is very hard. Ukraine gave up its nuclear weapons and it got guarantee of security, that its territory would be integral, it would not be attacked by any State and this guarantee was signed by several countries, like US, Britain and Russia. This security guarantee was violated in 2014 by Russia. After that I don’t think it would so easy for the society to trust guarantees any longer. We saw how the guarantee is not working. It doesn’t have any legal or any kind of consequences. It can be violated at any point.

So I don’t know how we can escape the alternative between Russia and NATO now. I don’t have an answer at the moment.

Probably you have seen the different statements against Russia’s invasion and in support of Ukrainian population. A Russian feminists’ call for standing against Putin’s regime and war. They say that this war is the continuation of everyday war waged against women, LGBTQI+ people and all those who are not supporting or rebelling against Putin’s regime. There have been several demonstrations and mobilizations against this war to denounce Putin’s responsibilities in different places in Europe and outside of Europe. What do you think about these initiatives? What can a transnational politics of peace do in this moment?

A lot of pressure should be put on Russia. There is no other way out. They went too far.

I am very grateful to all the mobilizations happening around the world. I have some hope on them because we see how the mobilizations are putting pressure on the governments of these countries. They are helping in humanitarian ways, not only in terms of military supplies, which are also important at this point. It is hard to keep the anti-militaristic position being in a country which was invaded by another country.

I am very grateful to people who mobilize in Russia. Some, who live there or abroad, are taking a very active part in organizing protests in Russia and also in supporting people who are fleeing Ukraine. In other countries also, mobilizing resources, providing information support, infrastructural support…

Now in Ukraine there is a lot of talks that one of the possible ways out is a rebellion inside Russia. I don’t believe it will happen. Unfortunately, because the civil society and self-organization in Russia and many countries of the post-Soviet state and possibly in Ukraine too, are quite weak and you cannot build them immediately in a situation like this. I don’t believe there will be something in Russian society which will stop Putin. Again, however sad it sounds, I would rather look for elite rebellion in Russia – this may change the situation substantially in short-term perspective.

What are the most urgent issues that women, workers and migrants, people in Ukraine as a whole, must face now?

The most urgent issue is the humanitarian support. Political pressure, even if it doesn’t make a big change, is still one of the things which could be definitely done. Unfortunately, not in Russia because they’re trying to block all the channels of information for people in Russia to see this, which is also a huge problem but we cannot do anything about it. Sometimes I have a feeling that there is some kind of wall built inside Europe.

I would like to raise also one thing which some leftist initiatives started to talk about. If we look in the future whatever it would be, one of the most important things is to give up on Ukrainian external debt because that’s an issue which is now discussed in some left initiatives, that IMF should give up on Ukrainian external debt in anyway because we will now need a lot of resources to rebuild the country. And there would be a possibility to make Ukrainian socio-economic policies more independent. This is also probably a demand which I hope – I know some people are already voicing it – will be more visible soon.

How to escape the geopolitical view according to which there are just states with their own interests at play while there are actually people who are suffering the direst consequences of political choices?

I totally agree that it would be good to escape this logic, but we cannot force people in government to escape it unfortunately. That’s where the choices are made, especially if you’re talking about autocratic states. It’s important, especially if we are reflecting about the situation, to see how differently it can be but it’s the logic which is imposed now. You cannot escape this level of analysis because it looks like that’s the level of analysis on which Putin is making decisions. His decisions and decisions of people around him are the most important factor in this situation now. This logic can be escaped when you have a society with quite a high level of civil society in general sense, like trade unions, but when you have a very hierarchical society where the power is built top-down and people have almost no influence on what is happening and which way they are moving and which decisions are taking, this level of analysis then it’s the only one which at least explains something. Unfortunately. I don’t feel comfortable with thinking in these terms, but I don’t know in which terms to think now. Some people now are trying to avoid this. They’re trying to get into some optimism regarding like how Ukrainians are self-organised, how they’re doing so much in recent days and building some networks of solidarity support. It’s very important, but I also understand that all this can be very easily destroyed because you deal with the country which is not trying to persuade anymore. Someone says that unlike Western hegemonies, the Russian state is not trying to build soft power. I don’t know whether they even tried but at this point it’s obvious they just don’t give a shit about it and they just rely on brute force very explicitly.

Apart from the solidarity in different humanitarian or different concrete ways to practise solidarity around the world with the refugees and sending food medicines and stuff, especially for refugees but not only: how do you see the role of transnational movements for peace or against this war? What can we do from a feminist, anti-exploitation, anti-racist point of view, apart from the concrete initiatives what can we do to grow a mobilisation that can overturn this situation?

Now it is a very hard time for this international grassroot or self-organised movement which is trying to build peace because it appeared suddenly – not suddenly for everybody but for many people suddenly – that the world has changed. Some of us, leftists, are too much used to live in one polar world and now it’s not like that. The best scenario is that the movement will need some time to rethink the conceptual framework of how we are thinking about this world, how we are thinking about the threats which are out there, that the threats are changing, they are developing, and the configuration of reality is already a little bit different. Without doing it there will be no move forward in this moment. If everything will be done correctly, if the lesson of the current moment will be understood correctly and if the movement will listen to the people on the ground, the movement will rethink this world and the threats to peace we have here because they are definitely changing. If this lesson will not be taken into account, then, unfortunately, the part of this movement that won’t take this into account, their rhetoric, actions and mobilizations, will not contribute meaningfully enough to the task which they want to achieve.

The transnational social strike platform wrote a statement against the war that was signed by many organizations in Europe at least. The perspective is to form a common transnational voice. Do you think that such attempts are going in the right direction?

This kind of attempt is already a part of that rethinking I was talking about. That’s why it’s important for the movement itself and for everything, for the vision of how to act in the nearest future. But there is also this danger of talking about peace at all costs. If we say we should restore peace at any costs, there is a dangerous trap: then let’s do whatever Russia is saying and they will stop the war, to save the lives of people.

This rhetoric is only a way out in a very short-term perspective, because if Russia comes here, they will put their government here – conservative, reactionary, oppressive, as it is now in Russia, or even worse. For example, for people like me and for many activists, feminists, leftists, LGBT activists, trade unionists, for journalists and opposition it would mean repressions, and it would also mean that, as I see it, from now, that the real partisan war would start. I’m afraid that the country will fall apart – with a lot of death and suffering. It’s not that Russia will come and stop doing everything that they have been doing in recent days in Ukraine and for many years in their own country, so that’s also very dangerous trap which some people also don’t understand.

We, the undersigned organizations, stand in solidarity with the people of Ukraine, but particularly Ukrainian journalists who now find themselves at the frontlines of a large-scale European war.

We, the undersigned organizations, stand in solidarity with the people of Ukraine, but particularly Ukrainian journalists who now find themselves at the frontlines of a large-scale European war.

“If leftists continue to blame NATO for the Russian invasion, they only show that they have not grasped the changed situation,” says Taras Bilous. The editor of the left-wing Ukrainian magazine Commons wrote a

“If leftists continue to blame NATO for the Russian invasion, they only show that they have not grasped the changed situation,” says Taras Bilous. The editor of the left-wing Ukrainian magazine Commons wrote a

This article, which originally appeared in Spanish in La Joven Cuba, the principal independent left-wing blog in Cuba, on Feb. 21, 2022, under the title “An Alternative for Cuba: political and economic democracy,” provides a critical perspective on the economic policies of the Cuban government and of some of its critics, and offers an alternative to both.

This article, which originally appeared in Spanish in La Joven Cuba, the principal independent left-wing blog in Cuba, on Feb. 21, 2022, under the title “An Alternative for Cuba: political and economic democracy,” provides a critical perspective on the economic policies of the Cuban government and of some of its critics, and offers an alternative to both.

The “Social Movement”’s appeal to Leftists around the world on how to help Ukraine stop Russian aggression and rebuild cities.

The “Social Movement”’s appeal to Leftists around the world on how to help Ukraine stop Russian aggression and rebuild cities.

The National Federation of Ports and Docks, CGT, calls all of the unions of Dock Workers and Port Workers to join together in solidarity for one hour and stop work between noon and 1:00 p.m. on Wednesday, March 16, “For PEACE and unity among all peoples.”

The National Federation of Ports and Docks, CGT, calls all of the unions of Dock Workers and Port Workers to join together in solidarity for one hour and stop work between noon and 1:00 p.m. on Wednesday, March 16, “For PEACE and unity among all peoples.”

The Unite executive council unreservedly condemns Putin’s invasion of Ukraine and stands in full solidarity with the millions of victims of the attack. Unite calls for an immediate cease-fire and a withdrawal of all Russian forces from Ukraine.

The Unite executive council unreservedly condemns Putin’s invasion of Ukraine and stands in full solidarity with the millions of victims of the attack. Unite calls for an immediate cease-fire and a withdrawal of all Russian forces from Ukraine.

This article from the Russian state propaganda publication RIA Novosti was to be published after the occupation of Ukraine but was accidentally published early and then removed. The Internet Archive web service, however, managed

This article from the Russian state propaganda publication RIA Novosti was to be published after the occupation of Ukraine but was accidentally published early and then removed. The Internet Archive web service, however, managed

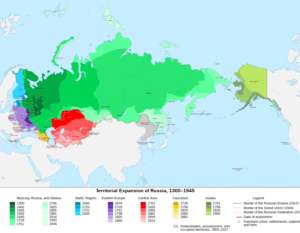

If someone suggested that we could understand the Black Lives Matter struggle without some knowledge of the historical background of slavery, lynchings, Jim Crow and so on, we would find it unconvincing, to put it mildly. But many on the left seem to think that they can comment on the crisis in Ukraine while being totally ignorant of that country’s history. I wish to argue, on the contrary, that it is impossible to understand what is happening in Ukraine today without some knowledge of its past, and to fill in some essential features of that past.

If someone suggested that we could understand the Black Lives Matter struggle without some knowledge of the historical background of slavery, lynchings, Jim Crow and so on, we would find it unconvincing, to put it mildly. But many on the left seem to think that they can comment on the crisis in Ukraine while being totally ignorant of that country’s history. I wish to argue, on the contrary, that it is impossible to understand what is happening in Ukraine today without some knowledge of its past, and to fill in some essential features of that past.

The International Trade Union Confederation and the European Trade Union Confederation condemn Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and demand that all Russian forces leave Ukraine immediately.

The International Trade Union Confederation and the European Trade Union Confederation condemn Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and demand that all Russian forces leave Ukraine immediately.

March 9, 2022

March 9, 2022