The Soul of the Bund: A Review of Yiddish Revolutionaries in Migration

Yiddish Revolutionaries in Migration: The Transnational History of the Jewish Labour Bund by Frank Wolff, translated by Loren Balhorn and Jan-Peter Herrmann, Haymarket Books, Chicago, 2022, paperback, 532 pp.

Frank Wolff begins his book, Yiddish Revolutionaries in Migration: The Transnational History of the Jewish Labour Bund, with the following quote from Daniel Cohn-Bendit (Moscow 2005):

Given that I’m in Russia now, I just happened to go through my bookshelf last night–because naturally I want to learn something about Russia. By coincidence, I came across this book. It’s the story if Marek Edelman, the last survivor of the Warsaw Ghetto struggle. And he in turn tells the story of the Bund. [With emphatic emphasis:] After all, who still knows the history of the Bund? (Laughter among the audience. We know, we know it…). It’s not a laughing matter. Because the memory of these people was destroyed by the Stalinists, the Zionists, by everyone. No one remembers this history…this first history…this attempt by workers to organize….They were all Jewish and spoke Yiddish, they didn’t want to go to Israel, they fought here in Russia, they fought in Lithuania, they fought in Poland, and their history has been totally erased by the traditional histories of the Zionists and the Stalinists.

Books and monographs have been published about the Bund, in Yiddish and English, German and Polish, and in other languages. Nevertheless, Cohn-Bendit’s remarks remain relevant. To fill the still-existing broad gap in knowledge of the Bund, before describing Frank Wolff’s book about the Bund, here are some facts that will give some notion of the “forgotten history” of the Bund.

The Bund was the first modern Jewish political party in the Russian Empire, as well as the largest social democratic movement in the entire empire. On the eve of the Second World War, it was also the strongest Jewish party in Poland.

In its early years (it was founded in 1897) the Bund achieved considerable success, attracting 40,000 supporters by 1906, making it the largest socialist group in the Russian Empire. From mid-1903 to mid-1904 the Bund held 429 political meetings, 45 demonstrations, and 41 political strikes; it issued 305 pamphlets, of which 23 dealt with the pogroms and self-defense. In 1904 the number of Bundist political prisoners reached 4,500.

In the 1930s, one hundred thousand Jewish workers belonged to Bundist unions, meaning that one-quarter of all unionized workers in Poland were led by the Bund, giving them enormous power. The Bund held the overwhelming majority in the national council of Jewish Trade Unions, which, at the end of 1921, comprised seven unions with 205 branches, and 46,000 members, and, in 1939, 14 unions with 498 branches and approximately 99,000 members.

Together with the left Labor Zionists, the Bund administered a network of secular Yiddish schools. At its peak, in the late 1920s, its TSYSHO (Tsentrale Yidishe Shul Organizatsye or Central Yiddish School Organization) maintained 219 institutions with 24,000 students, spread across 100 locations, including 467 kindergartens, 114 elementary schools, 6 high schools, 52 evening schools, and a pedagogical institute in Vilnius.

The Bund also maintained a youth organization, Tsukunft, which numbered 15,000 members on the eve of WW II, and a children’s organization, SKIF, blending scout activities, sports events, and politics; a women’s organization, YAF; and a sports organization, Morgnshtern, the largest such organization in all of Poland, Jewish or Polish.

In 1938, in the municipal elections in 89 Polish cities and towns, the Bund won 55% of the votes cast, more than all the other Jewish parties put together. The Bund thus became communal spokesmen and aggressive advocates of financial aid to all Jewish institutions, including yeshivas and religious institutions.

Most importantly, and as it relates to Frank Wolff’s book, being a member of the Bund meant you lived your life through the Bund—it was your union, your education, your church.

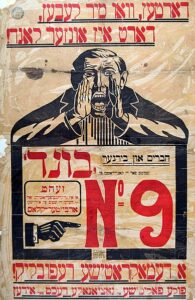

Bund election campaign poster. The Yiddish reads: “Wherever we live, that is our country. Comrades and citizens, vote for the candidates on Ticket No. 9. Ensure that at the founding assembly, the voice of the Jewish working class is heard. A democratic republic! Full political and national rights for Jews.”

During the years of the Holocaust, the Bund was in the forefront of Jewish resistance. Its years of illegal underground work under Tsarism, and then under the semi-fascist oppression in independent Poland between the wars, stood it in good stead. In every ghetto uprising, the Bundist youth movement stood shoulder to shoulder with the Zionist and communist youth to fight the Nazi murderers. Bundist annals of resistance are well-documented as arms smugglers, weapons makers, couriers, and suppliers of material and moral support to beleaguered Jews. They died fighting for Jewish honor.

As for their relation to the other political parties, as social democrats the Bund remained firmly anti-Communist. The Bund struggled with the Zionist movement for the hearts and minds of the Polish Jews. Looking back, one wonders how the Bund could have maintained that “There where we live (and have lived for hundreds of years), that is our country.” One forgets how chimerical the Zionist dream of a Jewish state in Palestine was. Herzl’s dictum that Palestine was “A land without people for a people without a land” was simply not true. Palestine was peopled by over 1 million Palestinians. In 1914, for example, Palestine’s non-Jews outnumbered Jews by 8 to 1.

The Bund argued that 3.2 million Polish Jews, and the other millions in Eastern Europe, would not pull up and move to Palestine. In any case, the Turks, and later the British, were not permitting Jews to enter. The practical and immediate thing to do was for the Jews in their millions to fight for their civil rights and for social democracy in the lands in which they were living, not dream of emigrating to Palestine.

It is tragically true that annihilation was the fate that befell the Polish and other East European Jews, but that same fate would have befallen the Jews of Palestine if the British army had not stopped the advance eastward of the German army with the British victory at El Alamein, Egypt. The Yishuv in Palestine would have been exterminated and with it would have perished the dream of a Jewish state in Palestine.

But all that history aside, why should anyone today, including of course primarily American Jews, care about a history of the Bund? Why should anyone care about the Bund at all for that matter? Frank Wolff provides some illuminating remarks about that question:

During Bernie Sanders’s first run for the Democratic presidential nomination, historian Daniel Katz pointed out that the key to understanding Sanders was not socialism as such but rather its specific Yiddish current….his fight against…oppression was informed by his experiences of Yiddish socialism….In this sense, the history of Yiddish socialism’s development as a transnational lifeworld presented in this book sheds light on a milieu that only a few years ago appeared anachronistic, but which in fact provided a recent presidential hopeful with profound appeal among young American voters. The history of the Bund as a party may have come to an end, but the effects of it cultural and political work and their unifying humanitarian yet activist spirit described here continue to matter today.

Frank Wolff’s book was first published in German in 2014 and now (2021) has been translated into English (Brill, Leiden & Boston). Wolff says the following in his Preface to the English translation: “Many surviving Bundists migrated overseas; few of them and their descendants read German. I am especially grateful that this translation makes my book available to them–it is, after all, their story.” It is also, I might add, a story for all of us.

Wolff’s well-documented book is not a traditional “history of the Bund.” These already exist in various books and monographs. These earlier, traditional histories are of the kind that tell of meetings, conventions, resolutions, party platforms, struggles with political opponents of the left and with Jewish nationalism. They are of the kind of traditional history that relates how one thing happened, then another happened, then this intraparty debate took place, that this wing or the other prevailed, and how a resolution was passed.

Wolff’s book, on the other hand, is what is these days called a “social, as well as a cultural, history.” What does that mean exactly? It means that, instead of focusing on events in the party’s history and on its politics or on what positions its intellectual leadership formulated for the party membership, Wolff focuses on that membership itself. What did its activism consist of? What did the Bund mean to them? How did they identify as Bundists? How did it change their lives? What did they then do about their lives, their livelihoods, their world?

The activism of the Bund consisted of strikes, demonstrations, Bundist militias fighting off antisemitic hooligans, protecting small Jewish shop-owners from fascist thugs, fighting gangsterism, fighting against communist attempts to control and dominate Jewish trade unions, reaching out to their fellow Polish social democrats to support each other’s candidates and to help in street battles.

Being a Bundist meant leaving the stultifying medieval world of supernatural piety and entering the enlightened, modern world. It meant acquiring a pride in their scorned mother tongue and its burgeoning literary culture. It meant, “straightening one’s back.”

It changed their lives. They were now part of a special, national culture. They were no longer victims. They fought back. They attended lectures and read. They acquired a new socialist lens through which to look at the world. They joined Bundist cultural circles where ideas, books, and philosophies were discussed. They joined the Bund’s athletic organization, Morgenstern. They had a home, a family, a circle of comrades, a hope for a better life. They never abandoned any of this, even when they migrated to America, Argentina, or even, yes, Israel.

Frank Wolff explains the essence of the Bundist ethos. The Bund, he reminds us, went into the gasn, tsu di masn (into the streets, to the masses). To be a Bundist meant to be a khaver (comrade), part of a mishpokhe (family), wedded to a secular Jewishness embodied in the Yiddish language and culture.

Wolff follows the Bundists as they migrate to New York and Buenos Aires, going to these places himself, interviewing surviving Bundists, digging into New York and Argentine archives for Bundist publications. He explores the question of how, why Bundists remained Bundists in their migration.

One cannot help but be impressed by the labor Frank Wolff expended to create this work. He did his research in five languages, including, of course, Yiddish. He read responses to over 500 autobiographical questionnaires put out by the YIVO and the Bund. He read books, journals, newspapers, and conducted interviews. His bibliography is over 80 pages long.

The book came out in an affordable paperback version this past December 2021. It is a masterful, scholarly, and insightful account of a powerful and important movement in modern Jewish history.

If one wants to understand the spirit, the culture, the soul of the Bund, one should read this book.