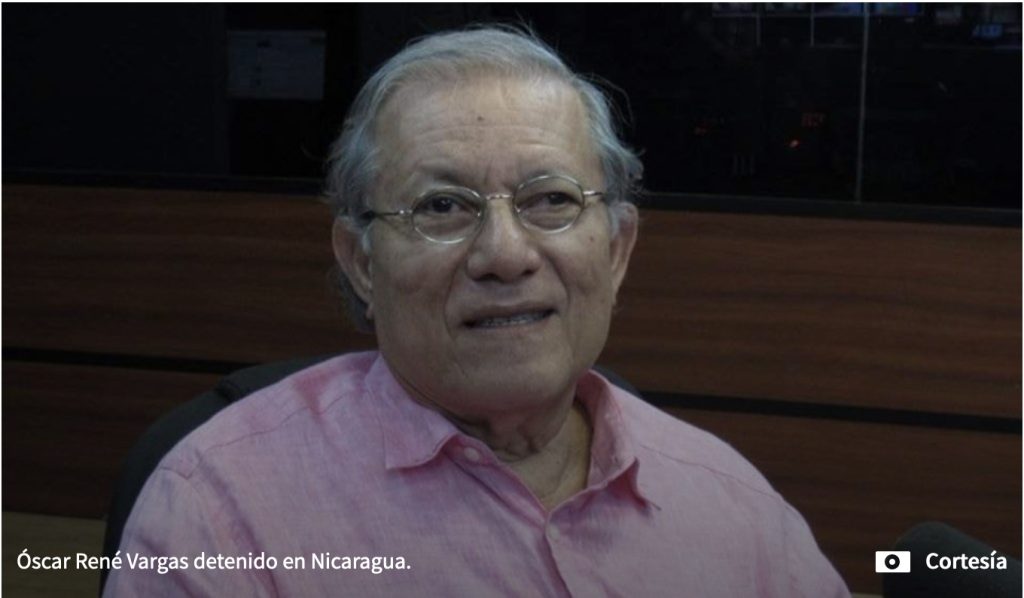

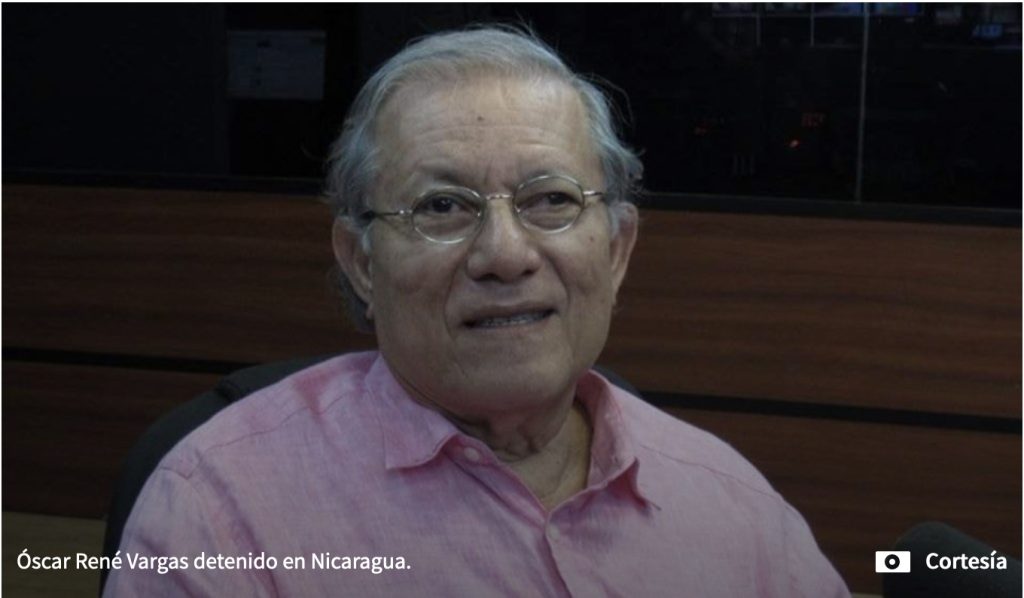

Oscar-René Vargas, a 77-year-old citizen of Nicaragua, is an economist, historian and current affairs analyst in Central America whose qualities are recognized in academic circles, especially by those who have constantly defended the social and democratic rights of the Nicaraguan people in the face of various authoritarian regimes.

Oscar-René Vargas, a 77-year-old citizen of Nicaragua, is an economist, historian and current affairs analyst in Central America whose qualities are recognized in academic circles, especially by those who have constantly defended the social and democratic rights of the Nicaraguan people in the face of various authoritarian regimes.

However, we learned of his “sequestration” –- his de facto arrest and imprisonment –- by the police of President Daniel Ortega’s regime on Tuesday, November 22, 2022. This arbitrary act shocks us deeply, especially since it prolongs a series of arrests of people critical, from various angles, of the current Nicaraguan regime.

Oscar-René Vargas is renowned for his numerous historical works -– more than 35 works -– on Nicaragua, as well as for his commitment, from the mid-1960s, against the Somoza dictatorship, his support for the initial government of the FSLN , and his support for the popular movement of demands that emerged in 2018. The commitments mentioned here reflect the ethical and political rectitude of Oscar-René Vargas, his attachment to democratic rights, and therefore to freedom of expression as well as that of of organization.

We ask the Nicaraguan authorities to fully respect the physical integrity of Oscar-René Vargas, all his rights of defense and his immediate release. Any possible future procedure must absolutely obey respect for human rights and international legal standards.

This requirement is in accordance with the Estatuto sobre derechos yguarantees de los Nicaraguenses, adopted by the Governing Board of National Reconstruction of the Republic of Nicaragua on August 21, 1979 and with the judgment passed in 1980 by the International Commission of Jurists (ICJ, Geneva ) which welcomed “the humanitarian concerns of the [new] government” (p. 6).

Our support for this call addressed to the present authorities of Nicaragua echoes these principles and values that Oscar-René Vargas defended then and still defends.” (November 23)

*****

First signatures gathered since November 23, closing on December 5

Central and South America

Mexico

Dr. Elena Lazos Chavero, Profesora-Investigadora Titular C, SNI III, Instituto de Investigaciones Sociales, Cd. Universitaria, Coyoacán, Ciudad de México

Manuel Aguilar Mora, escritor and professor, Universidad Autónoma de la Ciudad de México (UACM)

Rodrigo Díaz Cruz, professor-investigador Departamento de Antropología, UAM-I, México

Carmen de la Peza, professor-investigadora Universidad Autónoma Metropolitana, Departamento de Communication y Educación, UAM-X, México

Ana Lau Jaiven, professor-investigadora Universidad Autónoma Metropolitana, Departamento de Política y Cultura UAM-X, México

Ma. Eugenia Ruiz Velasco, professor-investigadora Universidad Autónoma Metropolitana, UAM, México

Gisela Espinosa Damián, professor-investigadora Universidad Autónoma Metropolitana, Departamento de Relaciones Sociales UAM. Directora de la revista Veredas , Mexico

Ángeles Eraña, professor-investigadora of the Instituto de Investigaciones Filosóficas, IIF, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, UNAM, México

Luis Bueno Rodríguez, professor-investigador Universidad Autónoma Metropolitana, UAM, CILAS, México

Gilberto López y Rivas, Profesor-investigador Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia, INAH, Morelos, México

Alicia Castellanos Guerrero, profesora-investigadora jubilada UAM-I, Mexico

Arturo Anguiano, professor-investigador Universidad Autónoma Metropolitana, UAM, México

Sonia Comboni Salinas, professor-investigadora Universidad Autónoma Metropolitana, UAM, México

Noemí Luján Ponce, professor-investigadora UAM, Mexico

Fernando Matamoros, professor of the Benemérita Universidad Autónoma de Puebla, BUAP, México

Araceli Mondragón, professor-investigadora Universidad Autónoma Metropolitana, UAM, México

Marcos Tonatiuh Águila Medina, professor-investigador Departamento de producción Económica, UAM-X, México

Mary Rosaria Goldsmith Connelly, professor-investigadora UAM-X, Mexico

Germán A. De la Reza, Profesor-investigador, UAM-X, Mexico

Telésforo Nava Vázquez, professor-investigador, UAM-I, Mexico

Adolfo Gilly, professor emerito, Facultad de Ciencias Políticas y Sociales, UNAM, Mexico

Gerardo Ávalos Tenorio, professor-investigador of UAM, Mexico

Margarita Zires, Profesora-investigadora of UAM, Mexico

Luis Hernández Navarro, Editorial Coordinator of La Jornada , Mexico

Mary Rosaria Goldsmith Connelly, professor-investigadora UAM-X, Mexico

Germán A. De la Reza, Profesor-investigador UAM-X, Mexico

Telésforo Nava Vázquez, Profesor-investigador UAM-I, Mexico

Julio Muñoz Rubio, Profesor Biólogo, Facultad de Ciencias, UNAM, México

Massimo Modonesi, Professor of Political and Social Sciences, UNAM, México

Dr. Gilberto Lopez y Rivas, professor investigator of INAH Morelos, Mexico

Carmen Aliaga, UAM Xochimilco, Mexico

Enrique Dussel Peters, Full Professor, Facultad de Economía de la Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México (UNAM), México

Alberto Arroyo Picard, Profesor Jubilado, Universidad autónoma metropolitana (UAM), México

Felipe Echenique March, investigator, Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia, México

José Manuel Juárez, professor-investigador of the Universidad autónoma metropolitana (UAM), México

Dr. Alejandro Valle Baeza, full professor, Facultad de Economía de la UNAM, Mexico

Arturo Taracena Arriola, Profesor Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México

Carlos Alberto Rios, Historian. Universidad Autonoma Metropolitana, Azcapotzalco, Mexico

Jérôme Baschet, historiador, Universidad Autonoma de Chiapas, México

Argentina

Maristella Svampa, investigator of CONICET, Argentina

Horacio Tarcus, Director of the Centro de Documentación e Investigación de la Cultura de Izquierda (CeDinci), Argentina

Rubén Lo Vuolo, Economist of the CIEEP, Argentina

Valeria Manzano, National University of San Martin, Argentina

Pablo Pozzi, Professor Consulto, University of Buenos Aires, Argentina

Pablo Bertinat, professor of the Universidad Tecnológica Nacional, Argentina

Mario Pecheny, Director del área de Ciencias Sociales y Humanidades del Consejo Nacional de Investigaciones Científicas y Técnicac (CONICET), Argentina

Julián Rebón, professor of the Universidad de Buenos Aires, Argentina

Roberto Gargarella, Professor University of Buenos Aires, Conicet, Argentina

Dra Ana Teresa Martinez, Instituto de Estudios para el Desarrollo Social (INDES), Universidad Nacional de Santiago del Estero/Consejo de Investigaciones Científicas y Tecnológicas (UNSE-CONICET), Argentina

Gabriel Puricelli, Professor, Facultad de Ciencias Sociales, University of Buenos Aires, Argentina

Eduardo Lucita, Economistas de Izquierda (EDI), Argentina

Sebastián Carassai, Investigador del CONICET, Regular Profesor, University of Buenos Aires (UBA), Argentina

Pablo Stefanoni, journalist, responsible for the review Nueva Sociedad , Argentina

Carlos Abel Suarez, Clasco, Buenos Aires, Argentina

Rolando Astarita, economist, Universidad Nacional de Quilmes and Universidad de Buenos Aires, Argentina

Brazil

Valério Arcary, professor titular aposentado do Instituto Federal de Educação, Ciência e Tecnologia de São Paulo, Brasil

Forrest Hylton, Visiting Professor of History, Universidade Federal da Bahia, Brasil

Ricardo Antunes, Full Professor, Universidade Estadual de Campinas (UNICAMP), Brasil

Breno Bringel, professor of the Universidad Estatal de Río de Janeiro, Brasil

José Mauricio Domínguez, professor of the Universidad Estatal de Río de Janeiro, Brasil

Pablo-Henrique Martins, Federal University of Pernambuco, Brasil

Paulo Nakatani, full professor at the Federal University of Espírito Santo, Brasil

Virgínia Fontes, historiadora, Universidade Federal Fluminense, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil

Ricardo Musse, Professor associado no departamento de sociologia da Universidade de São Paulo (USP), Brazil

Osvaldo Coggiola, professor titular, História contemporânea, Universidade de São Paulo (USP), Brazil

José Arbex, professor, Pontificia Universidade Catolica de São Paulo (PUC_SP), Brazil

Jorge Nóvoa, Full Professor, Universidade Federal da Bahia, Brazil

Nara HN Machado, Emeritus University Professor, Porto Alegre, Brazil

Robert Ponge, Professor, Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil

Luiz Renato Martins, professor, historiador, Universidade de São Paulo (USP), Brazil

Leda Paulani, full professor, Faculdade de Economia e Administração, Universidade de São Paulo (USP), Brazil

Rosa Maria Marques, Full Professor at the Pontifícia Universidade Católica de São Paulo , Brazil

Carlos Zacarias, Professor, historian of the Federal University of Bahia, Brazil

Bolivia

Mario Rodríguez, Fundacion Wayna Tambo, Bolivia

Elizabeth Peredo Beltran, Psicóloga e Investigadora, Observatorio de Cambio Climático y Desarrollo – OBCCD, Bolivia

Colombia

Muricio Archila, Professor Titular (pensionado), Universidad Nacional de Colombia

Daniel Libreros Caicedo, economist, professor, Universidad Nacional de Colombia, Bogotá

Alejandro Mantilla, professor of the Universidad Nacional de Colombia

Costa Rica

María Esther Montanaro Mena, cédula 1-0922-0124, Universidad de Costa Rica

Hans Nusselder, Consultor-investigador en desarrollo rural, San José, Costa Rica

Ecuador

Miriam Lang, professor at the Universidad Andina Simón Bolívar, Ecuador

Alberto Acosta, economist, former President of the Asamblea Constituyente de Ecuador

Chile

Dr. Haroldo Dilla Alfonso, Profesor Titular, Director of the Instituto de Estudios Internacionales (INTE), Universidad Arturo Prat, Chile

Guatemala

Ana Silvia Monzón, FLACSO, Guatemala

Dominican Republic

Virtudes de la Rosa, professor of the Univerrsidad Autónoma de Santo Domingo

Uruguay

Ramiro Chimuris, economist y abogado, Universidad de la República, Uruguay

Isabel Koifmann, trade unionist, Cooperativa Magisterial, Uruguay

Daniel Ceriotti, licenciado en Nutrición, Universidad de la República, Uruguay

Ernesto Herrera, periodista, Uruguay

Aldo Marchesi, Centro de Estudios Interdisciolinarios, Universidad de la República, Uruguay

Venezuela

Edgardo Lander, Central University of Venezuela

United States

Jeffrey L. Gould, Distinguished Visiting Professor of Modern History, School of Historical Studies, Institute for Advanced Study, Princeton, NJ, USA

Barbara Weinstein, Silver Professor of Latin American History, New York University, USA

Justin Wolfe, Associate Professor of History, Tulane University, USA

Jocelyn Olcott, Professor of History, Duke University, USA

Michel Gobat, Professor of History, University of Pittsburgh, USA

William I. Robinson Distinguished Professor of Sociology and Global and International Studies, Latin American and Iberian Studies, University of California-Santa Barbara, USA

Dan La Botz, Member of the Editorial Board of New Politics , New York, USA

Steven Volk, Professor of History Emeritus, Oberlin College, Ohio, USA

Dr. Julie A. Charlip, Professor Emerita, Latin American History, Whitman College, USA

Clara E Irazábal Zurita, JEDI Officer, ADVANCE Professor, School of Architecture, Planning and Preservation, University of Maryland, USA

John L. Hammond, Professor of sociology, City University of New York, former collaborator in the Casa del Gobierno, Estelí, 1985-86, United States

Rosalind Bresnahan, California State University San Bernardino (retired), USA

William Bollinger, Latin American Studies, California State University, Los Angeles, USA

Carlos Forment, professor, New School of Social Research, New York, USA

Greg Grandin, Chair Vann Woodward, Professor of History, Yale University, USA

Arturo Escobar, Prof. Emerito de Antropologia, U. of Carolina del Norte, Chapel Hill, USA

Amy C. Offner, Associate Professor of History, University of Pennsylvania, USA

William Aviles, Professor of Political Science, University of Nebraska at Kearney, USA

Howard Winant, Distinguished Professor Emeritus, Department of Sociology, University of California, Santa Barbara, USA

Stephen R. Shalom, emeritus professor, William Paterson University, New Jersey

Noam Chomsky, Institute Professor emeritus MIT, Laureate Professor U. of Arizona

Bill Fletcher, Jr., past president, TransAfrica Forum

Alan Wald, H. Chandler Davis Collegiate Professor Emeritus, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor

E. Ahmet Tonak, Professor of Economics, Hampshire College, USA

Canada

Jeffery R. Webber, Associate Professor, Department of Politics, York University, Toronto, Canada

Australia

Viviana Canibilo Ramírez, BA (Hons), Dip. Ed., Investigadora Independiente, Senior Teacher of Spanish & Home Economics (retired), NSW & Queensland Depts. of Education (1980-2016), Australia

Robert Austin Henry, Honorary Associate, School of Humanities, University of Sydney, Australia

France

Michael Löwy, Emeritus Research Director at CNRS, France

Eleni Varikas, Emeritus Professor at the University of Paris 8, France

Catherine Samary, economist, Paris Dauphine University

Gustave Massiah, former teacher at the Paris La Villette School of Architecture, France

Claude Serfati, economist, IRES, Paris

Franck Gaudichaud, university professor in Latin American history at Toulouse Jean Jaurès University, France

Christian Tutin, Emeritus University Professor, Paris-Est, France

Pierre Salama, Emeritus University Professor, Economist, Paris-Nord University, France

Jean Malifaud, lecturer at Paris Didedot University, mathematician, France

Alain Bihr, Honorary Professor of Sociology, University of Bourgogne-Franche-Comté (Besançon), France

Roland Pfefferkorn, Emeritus Professor of Sociology, University of Strasbourg, France

Bernard DREANO, economist, President of CEDETIM (Centre for studies and initiatives for international solidarity), France

Natacha Lillo, lecturer, Paris Cité University, France

Thomas Posado, doctor in political science at the University of Paris-8, France

Bruno Percevois, retired pediatrician, France

Olivier Compagnon, historian, Sorbonne Nouvelle University (Institute for Advanced Studies in Latin America), France

Hadrien Clouet, sociologist, deputy for Haute-Garonne

Hubert Krivine, Emeritus Professor of Physics, Pierre and Marie Curie University, France

Luc Quintin, MD, PhD, anesthesiologist (retired), senior investigator (retired), France

Claude Calame, Director of Studies, School of Advanced Studies in Social Sciences, France

Evelyne Perrin, sociologist, Stop Précarité and LDH 94 – French League for the Defense of Human Rights, France

Pierre Cours-Salies, professor emeritus Paris-8, France

John Barzman, Emeritus Professor of Contemporary History, University of Le Havre Normandy, France

Isabelle Garo, Philosopher, France

Christian Mahieux, Union Syndicale Solidaires, International Trade Union Network of Solidarity Aid Struggles, France

Carlos Agudelo, Sociologist, Associate Researcher URMIS, IRD – CNRS – University of Paris – University Côte d’Azur, France

Bruno Percevois, retired pediatrician, France

Natacha Lillo, lecturer, Paris Cité University, France

Laurent Faret, Professor of Geography at Paris-Diderot University, France

Janette Habel, Lecturer at the University of Marne-la-Vallée and at IHEAL, France

Ludivine Bantigny, Historian, Paris, France

Pierre Khalfa, Economist, Copernic Foundation, France

Nicole Abravanel, School of Advanced Studies in Social Sciences, France

Christiane Vollaire, Philosopher, Associate Researcher at CNAM, Paris, France

Esther Jeffers, Professor of Economics, University of Picardie Jules Verne, France

Gilles Bataillon, Sociologist, School of Advanced Studies in Social Sciences, Paris, France

Pierre ROLLE, sociologist, University of Paris-Nanterre, France

Pierre Dardot, philosopher, University of Paris Nanterre, France

Edgard Vidal–Martinez, Center for Research on Arts and Language (EHESS-Paris), France

Christian Laval, Emeritus Professor of Sociology, Paris-Nanterre University, Paris, France

Marc Perelman, Emeritus Professor of Universities, Paris Nanterre University, France

Michel Cahen, CNRS Emeritus Research Director at Sciences Po Bordeaux, France

Josette Trat, sociologist, former teacher-researcher at the University of Paris 8, France

Robert March, Emeritus Lecturer, Faculty of Architecture, Paris, France

Jacques Généreux, University lecturer at Sciences Po. Paris, France

Charlotte Guénard, economist, University Paris 1 Panthéon-Sorbonne-IEDES, Paris, France

Belgium

Bernard Duterme, Director CETRI – Tricontinental Center, Belgium

Mateo Alaluf, Honorary Professor Free University of Brussels, Belgium

Andrea Rea, professor at the Free University of Brussels, Belgium

Pierre Marage, Professor Emeritus of the Free University of Brussels, Belgium

Anne Morelli, Professor Emeritus of the Free University of Brussels, Belgium

Marcelle Stroobants, Emeritus Professor of the Free University of Brussels, Belgium

Jean Vogel, teacher Free University of Brussels, Belgium

Éric Toussaint, Doctor of Political Science from the Universities of Paris 8 and Liège, Belgium

Hugues Le Paige, journalist-director, Belgium

Isabelle Stengers, Emeritus Professor Free University of Brussels, Belgium

Francine Bolle, professor at the Free University of Brussels, Belgium

Esteban Martinez, professor Free University of Brussels, Belgium

Fréderic Louault, professor Free University of Brussels, Belgium

Margaux De Barros, Researcher at the Free University of Brussels, Belgium

Laurent Vogel, associate researcher at the European Trade Union Institute, Belgium

Christine Pagnoulle, Honorary Professor at the University of Liège, Belgium

Sylvie Carbonnelle, Assistant in charge of exercises, Institute of Sociology, Free University of Brussels, Belgium

Jean Vandewattyne, Professor, University of Mons, Belgium

Douglas Sepulchre, assistant at the Free University of Brussels, Belgium

Riccardo Petrella, Emeritus Professor of the Catholic University of Louvain (B), Political Economist, Belgium

Perrine Humblet, Professor Emeritus of the Free University of Brussels, Belgium

Corinne Gobin, Emeritus Professor of the Free University of Brussels, Belgium

Michel Caraël, Professor Emeritus of the Free University of Brussels, Belgium

Willy Estersohn, Journalist, Belgium

Jean Puissant, Emeritus Professor Free University of Brussels, Belgium

Ralph Coeckelberghs, former Secretary General of Socialist Solidarity-NGO active in Nicaragua, Belgium

Eric Corijn, Professor of Urban Studies, Vrije Universiteit Brussel (VUB), Belgium

Pierre Galand, Emeritus University Professor, ULB, Belgium

Alexis Deswaef, lawyer at the Brussels Bar and vice-president of the International Federation for Human Rights (FIDH), Belgium

Patricia Willson, Faculty of Philosophy and Letters, University of Liège, Belgium

Sixtine Van Outryve, doctoral student in law, Catholic University of Louvain, Belgium

Maria Cecilia Trionfetti, researcher, Faculty of Philosophy and Social Sciences, Free University of Brussels, Belgium

Louise de Brabandère, doctor affiliated with the Institute of Sociology of the Free University of Brussels (ULB), Belgium

Netherlands

Tatiana Roa, professor Center for Latin American Research and Documentation Cedla, Amsterdam University, Netherlands

Britain

Alex Callinicos, Emeritus Professor of European Studies, King’s College London

Gilbert Achcar, Professor, SOAS, University of London

Alfredo Saad Filho, Professor, King’s College London

Elisa Van Waeyenberge, Professor, SOAS, University of London

Chris Wickham, Chichele Professor of Medieval History emeritus, University of Oxford, Great Britain

Mike Gonzalez, Emeritus professor, Glasgow university, U.K.

Ken Loach, filmmaker

Spain

Jaime Pastor, Professor of Political Science at the National University of Distance Education (UNED), Madrid, Spain

Marcos Roitman, Professor of Sociology at the Complutense University of Madrid, Spain

Luisa Martín Rojo, Catedrática de Lingüística of the Universidad Autónoma de Madrid, Spain

María Trinidad Bretones, titular professor of Sociology at the Universidad de Barcelona, Spain

Antonio García-Santesmases, catedrático de Filosofía Política of the Universidad Nacional de Educación a Distancia , Spain

Roberto Montoya, writer and periodist, Spain

Carlos Prieto Rodriguez, Professor Emeritus of the Complutense University of Madrid, Spain

Ángeles Ramírez, full professor of social anthropology at the Universidad Autónoma de Madrid, Spain

Fernando Álvarez-Uría, Catedrático de Sociología of the Universidad Complutense de Madrid (UCM), Spain

Julia Varela, Catedrática de Sociología of the Universidad Complutense de Madrid (UCM), Spain

Álvaro Pazos Garciandia, professor of Social Antropology of the Universidad Autónoma Madrid, Spain

Carlos Giménez Romero, professor of Social Antropology of the Universidad Autónoma Madrid, Spain

Juan Carlos Gimeno Martín, professor of Social Antropology of the Universidad Autónoma Madrid, Spain

Marta Cabezas Fernandez, professor of Social Antropology of the Universidad Autónoma Madrid, Spain

Virtudes Téllez Delgado, secretaria académica, Universidad Autónoma, Madrid, Spain

Alba Valenciano i Mañé, professor of Social Antropology of the Universidad Autónoma Madrid, Spain

Alessandro Forina, professor of Social Antropology of the Universidad Autónoma Madrid, Spain

Fructuoso de Castro, professor of Social Antropology of the Universidad Autónoma Madrid, Spain

Pilar Monreal Requena, professor of Social Antropology of the Universidad Autónoma Madrid, Spain

Alicia Campos Serrano, professor of Social Antropology of the Universidad Autónoma Madrid, Spain

Juan Ignacio Robles Picón, professor of Social Antropology of the Universidad Autónoma Madrid, Spain

Paloma Gómez Crespo, professor of Social Antropology of the Universidad Autónoma Madrid, Spain

Héctor Grad, professor of Social Antropology of the Universidad Autónoma Madrid, Spain

Virginia Vaqueira, professor of Social Anthropology of the Universidad Autónoma Madrid, Spain

Carlos Taibo, professor of Ciencia Política de la Universidad Autónoma Madrid, Spain

Maria de la Válgoma, titular professor of Derecho Civil, Universidad Complutense de Madrid, España

Alberto Riesco, Professor Complutense University of Madrid, Spain

Julia Peregrin Caballero, Socióloga, Experta en Cooperación Internacional, Madrid, Spain

Italy

Luigi Ferrajoli, professor emerito di “Filosofia del diritto” presso the Università degli Studi Roma Tre, Doctor honoris causa of many universities: Buenos Aires (UBA), Universidad Nacional de La Plata, Universidad de la Repubblica del Uruguay, Academia Brasileira de Direito Constitucional (Curitiba, Brasil), etc.

Pietro Basso, Professore associato di Sociologia – Università Ca’ Foscari / Venezia, Italy

Riccardo Bellofiore, Economista, Italy

Michele Fatica, professor emerito di storia moderna e contemporanea at the Università “L’Orientale” di Napoli, Italy

Paolo Barcella, Professore associato, Dipartimento di Lingue, Letterature e culture straniere, University of the studi di Bergamo, Italy

Portugal

Alda Sousa, University of Porto, Biomedical Sciences, Portugal

Jorge Sequeiros, University of Porto, Medicine, Portugal

Ana Campos, New University of Lisbon, medicine, Portugal

Francisco Louçã, University of Lisbon, economy, Portugal

Boaventura de Sousa Santos, Director Emérito Centro de Estudos Sociais, Portugal

Switzerland

Jean Ziegler, emeritus professor of sociology at the University of Geneva, vice-president of the advisory committee of the United Nations Human Rights Council, Switzerland

Sébastien Guex, Honorary Professor University of Lausanne, Switzerland

Bernard Votat, Ordinary Professor, University of Lausanne, Switzerland

Sandra Bott, Assistant Professor, Faculty of Letters, University of Lausanne, Switzerland

Silvia Mancini, Honorary Professor, Faculty of Theology and Religious Studies, University of Lausanne, Switzerland

Malik Mazbouri, Lecturer and Researcher, Faculty of Letters, University of Lausanne, Switzerland

Jean Batou, Honorary Professor, Faculty of Social and Political Sciences, University of Lausanne, Switzerland

Joseph Daher, Visiting Professor, Faculty of Social and Political Sciences, University of Lausanne, Switzerland

Stéfanie Prezioso, Associate Professor, Faculty of Social and Political Sciences, University of Lausanne, Switzerland, Member of the Federal Parliament

Janick Marina Schaufelbuehl, Associate Professor, Faculty of Social and Political Sciences, University of Lausanne, Switzerland

Nils de Dardel, lawyer, former federal parliamentarian, Geneva, Switzerland

Romolo Molo, lawyer, Geneva, Switzerland

Hans Leuenberger, retired ICRC delegate, Switzerland

Nelly Valsangiacomo, Full Professor, Faculty of Letters, University of Lausanne, Switzerland

Charles-André Udry, economist, Editions Page 2, Switzerland

Nicolas Bancel, Full Professor, Faculty of Social and Political Sciences, University of Lausanne, Switzerland

Pierre Eichenberger, Lecturer and Researcher, Faculty of Social and Political Sciences, University of Lausanne, Switzerland

Pierre Frey, Honorary Professor Federal Polytechnic School, Lausanne, Switzerland

Caroline RENOLD, lawyer, Geneva, Switzerland

Pierre STASTNY, lawyer, Geneva, Switzerland

Maurizio LOCCIOLA, lawyer, Geneva, Switzerland

Christian Dandres, Lawyer, Member of the Federal Parliament, Geneva, Switzerland

Emmanuel Amoos, Member of the Federal Parliament, Valais, Switzerland

Laurence Fehlmann Rielle, Member of the Federal Parliament, Geneva, Switzerland

Nicolas Walder, Member of the Federal Parliament, Geneva, Switzerland

Dr Martine Rais, physician, Switzerland

Cédric Wermuth, Member of the Federal Parliament, Aargau, Switzerland

Pierre-Yves Maillard, Member of the Federal Parliament, Vaud, Switzerland

Sébastien Chauvin, Associate Professor, Faculty of Social and Political Sciences, University of Lausanne, Switzerland

Michel Ducraux, retired ICRC delegate, Switzerland

Cécile Péchu, Lecturer and Researcher, University of Lausanne, Switzerland

Matthieu Leimgruber, Ausserordentlicher Professor Forschungsstelle für Sozial- und Wirtschaftsgeschichte, Universität Zürich, Switzerland

Mounia Bennani-Chraïbi, Full Professor, Faculty of Social and Political Sciences, University of Lausanne, Switzerland

Katharina Prelicz-Huber, Member of Federal Parliament, Zurich, Switzerland

Lisa Mazzone, Member of the Federal Parliament, Geneva, Switzerland

Brigitte Crottaz, Member of the Federal Parliament, Vaud, Switzerland

Léonore Porchet, Member of the Federal Parliament, Vaud, Switzerland

Christophe Clivaz, Member of the Federal Parliament, Valais, Switzerland

Delphine Klopfenstein-Broggini, Member of the Federal Parliament, Geneva, Switzerland

Natalie Imboden, Member of Federal Parliament, Bern, Switzerland

Balthasar Glättli, Member of the Federal Parliament, Zurich, Switzerland

Hans-Peter Renk, retired librarian, Le Locle, Switzerland

Sergio Rossi, Full Professor, Faculty of Economics and Social Sciences and Management, University of Fribourg, Switzerland

Christian Marazzi, Professor, La Scuola universitaria professionale della Svizzera italiana, Lugano-Tessin, Switzerland

Spartaco Greppi, Professor, Dipartimento di economia aziendale, sanità e sociale, SUPSI, Lugano-Tessin, Switzerland

Austria

Dr. Leo Gabriel, Periodista y Antropólogo, Austria

Christian Zeller, Professor für Wirtschaftsgeographie an der Universität Salzburg, Austria

Germany

Dr. Manfred Liebel, Prof. em. Technische University Berlin, Germany

Dr. Betina Kern, Ambassador of the Federal Republic of Germany from 2008 to 2012 in Nicaragua, Germany

For the latest signatories, see here.

Faced with the invasion of Ukraine by the regime of Vladimir Putin, the antiwar movement has seen the development of very contrasting positions. They all have in common that they all claim peace, a word behind which very diverse, even opposing attitudes can be placed.

Faced with the invasion of Ukraine by the regime of Vladimir Putin, the antiwar movement has seen the development of very contrasting positions. They all have in common that they all claim peace, a word behind which very diverse, even opposing attitudes can be placed.

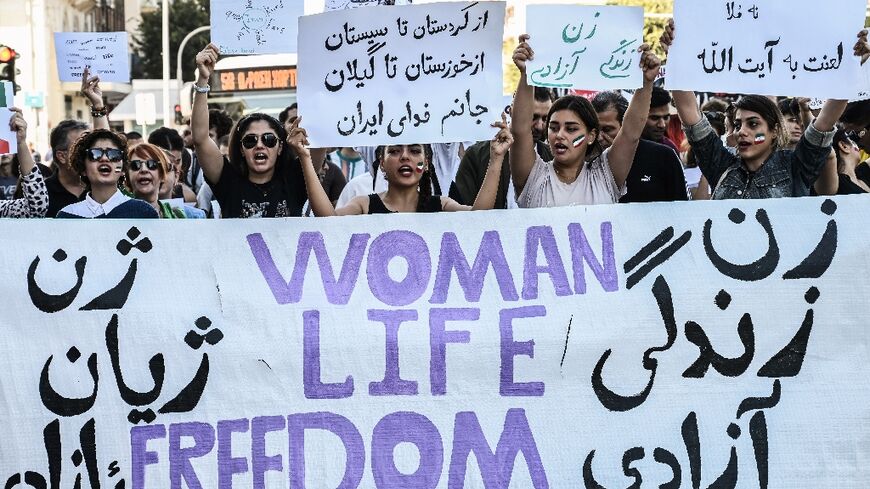

We, Ukrainian feminists, express our solidarity with Iranian uprising, triggered by the

We, Ukrainian feminists, express our solidarity with Iranian uprising, triggered by the

Oscar-René Vargas, a 77-year-old citizen of Nicaragua, is an economist, historian and current affairs analyst in Central America whose qualities are recognized in academic circles, especially by those who have constantly defended the social and democratic rights of the Nicaraguan people in the face of various authoritarian regimes.

Oscar-René Vargas, a 77-year-old citizen of Nicaragua, is an economist, historian and current affairs analyst in Central America whose qualities are recognized in academic circles, especially by those who have constantly defended the social and democratic rights of the Nicaraguan people in the face of various authoritarian regimes.

Since July 11, 2021, when there were many street protests throughout the nation’s territory, Cuba has been in a state of persistent agitation. According to the Cuban blog El Toque, between September 28 and October 12, ninety-two protests took place in thirty-six municipalities, twelve of them located in Havana’s metropolitan area. These were due to a large extent to the damages caused by hurricane Ian, including a nation-wide blackout. Many Cubans went out to protest in the streets, helped by the darkness that made more difficult their identification by the repressive organs of the state. Although this blackout was very extensive and long-lasting, it has not been the only one in recent times caused by the lack of maintenance, official negligence, and energy shortages due to a significant degree to the reduction of oil shipments from Venezuela. The long blackout resulted in thousands of Cubans losing their refrigerated food, worsening the already critical food situation.

Since July 11, 2021, when there were many street protests throughout the nation’s territory, Cuba has been in a state of persistent agitation. According to the Cuban blog El Toque, between September 28 and October 12, ninety-two protests took place in thirty-six municipalities, twelve of them located in Havana’s metropolitan area. These were due to a large extent to the damages caused by hurricane Ian, including a nation-wide blackout. Many Cubans went out to protest in the streets, helped by the darkness that made more difficult their identification by the repressive organs of the state. Although this blackout was very extensive and long-lasting, it has not been the only one in recent times caused by the lack of maintenance, official negligence, and energy shortages due to a significant degree to the reduction of oil shipments from Venezuela. The long blackout resulted in thousands of Cubans losing their refrigerated food, worsening the already critical food situation.

[Prague] Anna Ŝabatová knows what it is to fight Russian imperialism. In the 1970s she and her husband Peter Uhl, who died last year, were active in Czechoslovakia in the movement for democracy, human rights, and national sovereignty. Both served time in prison for their opposition to the government. Today Ŝabatová has joined a group of women who are fellow veterans of the fight against the Czech Communist government and the Soviet Union’s domination of their country in a network called Grandmothers with Ukraine.

[Prague] Anna Ŝabatová knows what it is to fight Russian imperialism. In the 1970s she and her husband Peter Uhl, who died last year, were active in Czechoslovakia in the movement for democracy, human rights, and national sovereignty. Both served time in prison for their opposition to the government. Today Ŝabatová has joined a group of women who are fellow veterans of the fight against the Czech Communist government and the Soviet Union’s domination of their country in a network called Grandmothers with Ukraine.

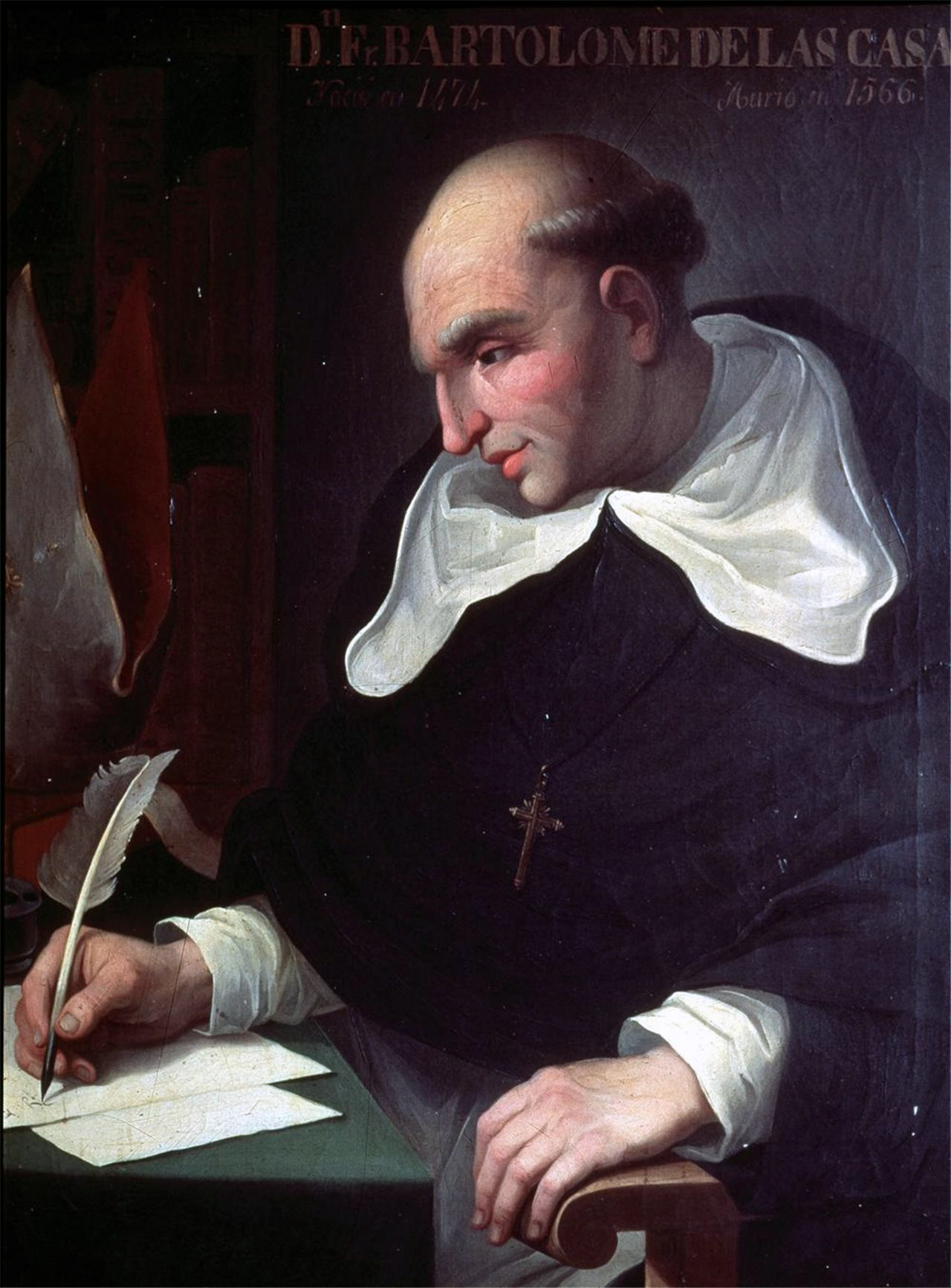

Over 400 years ago, long before Woodrow Wilson or Vladimir Lenin, the Christian humanist Bartolomé de Las Casas, known as the “Defender of the Indians,” developed a theory of the right of nations to self-determination that can be applied to many other countries today, including Ukraine.

Over 400 years ago, long before Woodrow Wilson or Vladimir Lenin, the Christian humanist Bartolomé de Las Casas, known as the “Defender of the Indians,” developed a theory of the right of nations to self-determination that can be applied to many other countries today, including Ukraine.

As usual, given the kingdom’s dominant weight in the global oil market, the Saudi role was decisive in the decision taken a week ago by OPEC+, i.e. the expanded OPEC that includes a number of non-OPEC oil-exporting countries, most notably Russia. This decision, which called for the reduction of oil production in order to maintain the level of prices, caused a major international uproar, especially in the United States, not because of its actual impact on the oil market as much as for its significance regarding the US-Saudi relationship. This is because OPEC production during the months preceding the meeting was already below the previously set ceiling due to the inability of many countries to increase their production for technical reasons, while other countries, including the United Arab Emirates, want to increase their production after having invested in strengthening their extractive capabilities.

As usual, given the kingdom’s dominant weight in the global oil market, the Saudi role was decisive in the decision taken a week ago by OPEC+, i.e. the expanded OPEC that includes a number of non-OPEC oil-exporting countries, most notably Russia. This decision, which called for the reduction of oil production in order to maintain the level of prices, caused a major international uproar, especially in the United States, not because of its actual impact on the oil market as much as for its significance regarding the US-Saudi relationship. This is because OPEC production during the months preceding the meeting was already below the previously set ceiling due to the inability of many countries to increase their production for technical reasons, while other countries, including the United Arab Emirates, want to increase their production after having invested in strengthening their extractive capabilities.

21st Century Revolution: through higher love, racial justice and democratic cooperation, Ted Glick, Bloomfield, NJ: Future Hope Publications, 2021, 114 pp. $10,

21st Century Revolution: through higher love, racial justice and democratic cooperation, Ted Glick, Bloomfield, NJ: Future Hope Publications, 2021, 114 pp. $10,

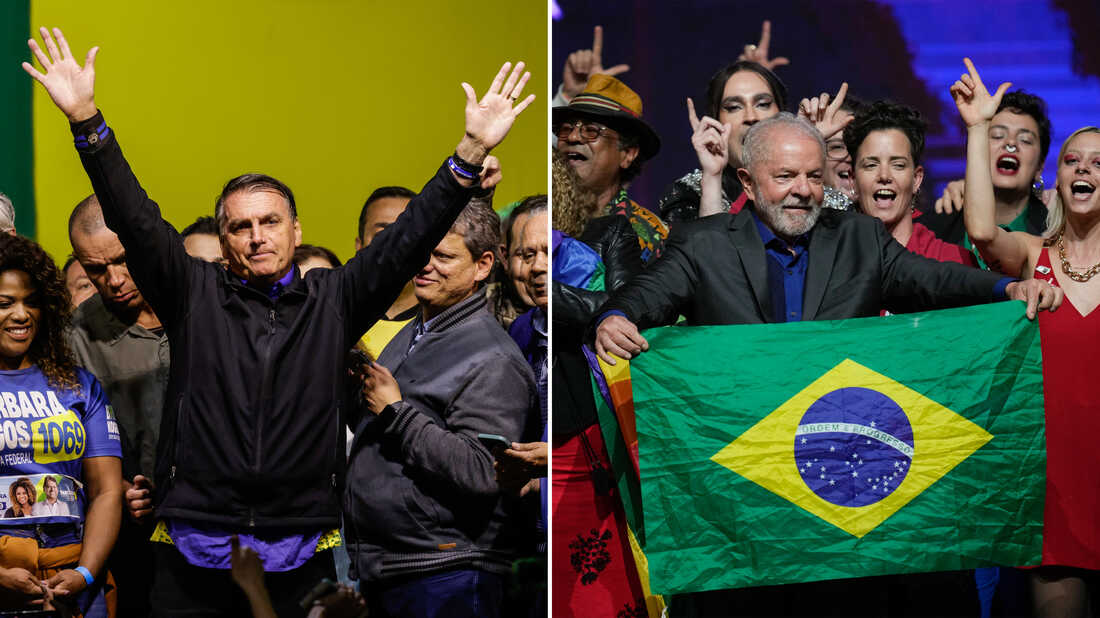

The United States has long dominated Latin America, but today—in fact for the last twenty years—it is being challenged by China, which has invested billions and established political and some military relationships with many governments in the region. The U.S. took control of Latin America first through wars and later through economic investment, China has begun with economic investment, but as we know from history, defending such investments often requires war. One can foresee a sharpening of U.S.-Chinese inter-imperialist competition in Latin America today.

The United States has long dominated Latin America, but today—in fact for the last twenty years—it is being challenged by China, which has invested billions and established political and some military relationships with many governments in the region. The U.S. took control of Latin America first through wars and later through economic investment, China has begun with economic investment, but as we know from history, defending such investments often requires war. One can foresee a sharpening of U.S.-Chinese inter-imperialist competition in Latin America today.

A review of Fighting Times: Organizing on the Front Lines of the Class War (PM Press, 2022) by Jon Melrod and Troublemaker: Saying No to Power by Frank Emspak (available at Amazon books).

A review of Fighting Times: Organizing on the Front Lines of the Class War (PM Press, 2022) by Jon Melrod and Troublemaker: Saying No to Power by Frank Emspak (available at Amazon books). At the time, they and their closest comrades were not exactly the best of friends or workplace allies. As Emspak reports in his memoir, Troublemaker, he came from a distinguished old left labor family. His father Julius, was a key organizer and longtime national officer of the United Electric Workers (UE), a union built with the help of Communist Party (CP) members or sympathizers in the 1930s. Melrod made his personal post-graduate turn toward industry as part of a group affiliated with the Revolutionary Union (RU), a Bay Area formation that later morphed into the Revolutionary Communist Party (RCP). RCP cadre considered the CP to be a case study in Marxist-Leninist “revisionism” and were not fond of its labor work either. Both authors are trying to reach an audience of 21st century socialists who are, in some cases, young enough to be their grand-children. To most (but not all) in that new generational cohort, differences between the CP, the RCP, and other “alphabet soup” groups from the sectarian left of five decades ago will be of minimal interest. What will hopefully draw readers to Troublemaker and Fighting Times are their granular lessons about building left-led union reform caucuses, which can actually oust old guard officials and replace them with rank-and-file militants more committed to membership mobilization and strike activity.

At the time, they and their closest comrades were not exactly the best of friends or workplace allies. As Emspak reports in his memoir, Troublemaker, he came from a distinguished old left labor family. His father Julius, was a key organizer and longtime national officer of the United Electric Workers (UE), a union built with the help of Communist Party (CP) members or sympathizers in the 1930s. Melrod made his personal post-graduate turn toward industry as part of a group affiliated with the Revolutionary Union (RU), a Bay Area formation that later morphed into the Revolutionary Communist Party (RCP). RCP cadre considered the CP to be a case study in Marxist-Leninist “revisionism” and were not fond of its labor work either. Both authors are trying to reach an audience of 21st century socialists who are, in some cases, young enough to be their grand-children. To most (but not all) in that new generational cohort, differences between the CP, the RCP, and other “alphabet soup” groups from the sectarian left of five decades ago will be of minimal interest. What will hopefully draw readers to Troublemaker and Fighting Times are their granular lessons about building left-led union reform caucuses, which can actually oust old guard officials and replace them with rank-and-file militants more committed to membership mobilization and strike activity.