The uneasiness and disorientation that can seize the observer in the face of the various crises (economic, political, cultural, social and moral) that Italian society has been going through for the last thirty years are multiplied tenfold by the feeling that the horizon is moving away, while there no longer seems to be any shore to cling to. The image of a ship adrift, or of a boat without a paddle, is one of the most telling in a period where there no longer seems to be any vision of the future. We are on the eve of the Italian election–and the black tide of fascism is still rising.

The uneasiness and disorientation that can seize the observer in the face of the various crises (economic, political, cultural, social and moral) that Italian society has been going through for the last thirty years are multiplied tenfold by the feeling that the horizon is moving away, while there no longer seems to be any shore to cling to. The image of a ship adrift, or of a boat without a paddle, is one of the most telling in a period where there no longer seems to be any vision of the future. We are on the eve of the Italian election–and the black tide of fascism is still rising.

On September 25 Italy will hold elections following the resignation of Prime Minister Mario Draghi and the concern is palpable. The Economist wrote that they could hardly come at a less opportune time, in the midst of at least three interconnected crises: the invasion of Ukraine, the energy crisis and inflation, which in late August reached 8.4% in Italy, its highest level since 1986. In addition, Italy’s debt is currently 150% of its GDP, which is “the largest proportion of debt held by residents of any large eurozone country.”[1] Finally, as the Financial Times pointed out, governments and investors are wondering what impact Mario Draghi’s departure will have on the EU’s 800 billion Covid stimulus fund, of which Italy is the main beneficiary.[2] Economic market fears are also focused on the rise in the spread, i.e. the difference between the yield on Italian government securities and German ten-year bonds, which reached a two-year high in June, a true “political thermometer.”

The outgoing President of the Council announced on August 5 that he wanted to go to New York to “reassure investors,” a step that could pave the way for a new “technical” government in the unlikely event that there is not a sufficient majority to form an executive after the elections; an option favored not only abroad but also in Italy by a significant part of the bourgeoisie, who stress to anyone who will listen that the economic policy agenda set by Mario Draghi remains the yardstick by which the next government must be measured: “Yet any significant disruption or deviation from the reform and investment programme, laid out in a 664-page annex to Rome’s deal with the commission, would jeopardise Italy’s full access to the funds,” writes Amy Kazmin in Financial Times.[3] An agenda he had already set in 2011 when he was head of the ECB. An agenda based on massive cuts in the system of social insurance and protection for the unemployed, wage earners and pensioners in a country that has brought about a massive increase in poverty in recent years, reaching an all-time high of some 5.6 million people in absolute poverty by 2021.[4]

The concern is all the more palpable because the coalition of the right and the extreme right has a strong probability of gaining the majority this time: the polls give it more than 45%; with the electoral law, this coalition could obtain 70% of the seats in parliament. The announced victory of Giorgia Meloni, leader of the Fratelli d’Italia (FdI) party, and her possible arrival at the head of the government is a serious threat for a party in whose arteries fascism still circulates and whose logo proudly displays the symbol of the tricolor flame in the center representing the still living spirit of fascism.[5] FdI has its roots in post-war neo-fascism, a direct heir, both in terms of militant personnel and political traditions and cultures, to the fascist experience, such as that of Giorgio Almirante, an enthusiastic fascist, editor in the 1930s of the anti-Semitic magazine La Difesa della razza, who joined the ranks of the Salò Republic in 1943, and after the war founded the Italian Social Movement (MSI), whose legacy Meloni proudly claims. FdI’s support has steadily increased, from 1.96% of the vote in 2013 to 4.35% in 2018 [6] ; today some 25% of voters say they would vote for it. As the centenary of Mussolini’s March on Rome approaches, post-fascism seems to be at the gates of power in Italy. A counter-revolution without a concomitant revolutionary process, a phenomenon described in his time by Antonio Gramsci as “passive revolution.”

Now, beyond the snapshot offered every day by a wide range of political scientists, philosophers, activists, sociologists, it is important to try to understand how we arrived at this disaster, in order to grasp the contours of a “change of era,” to go back to the source and see where the (ir)resistible rise of the worst possible outcome—embodied by a nationalist, racist, reactionary, patriarchal right—begins.

More than thirty years of the black tide

The fear of a “return of fascism” occurs at regular intervals in the country that saw its birth a century ago. The international press has been focusing for some weeks on Giorgia Meloni and her movement, forgetting in passing that she is not a newcomer to the coalition of Silvio Berlusconi, who appointed her Minister of Youth in 2008, and reinforcing the idea that she is the only newcomer in the relatively large field of parties that call themselves “anti-systems;” also failing to highlight the enduring ties of Matteo Salvini’s Lega with the neo-fascists, their “captain,” of the 2018 elections. At the time, the presence of Matteo Salvini in the ranks of the right-wing coalition, together with Silvio Berlusconi’s party, Forza Italia, and Giorgia Meloni’s Fratelli d’Italia, reactivated the same fears; all the more so as the 80% of Italians polled then affirmed the need for a “strong man” to emerge from the crisis and those who thought that democracy was the best possible form of government reached their lowest level since 2008 (62%, or minus 10 percentage points in ten years).[7] A proportion that has slightly increased today to about 70%, although the demand for a strong leader remains in the majority (some 59% of Italians surveyed).[8]

Silvio Berlusconi’s party, which had been the driving force of the right-wing coalition before 2018 has been slowly disappearing. But the change in the balance of power within it is a change in the degree, not the nature, of the coalition invented by Silvio Berlusconi more than a quarter of a century ago, uniting the conservative and reactionary right, the “new” far right and neo- or post-fascist organizations. After all, hadn’t Berlusconi himself been “compared” to Benito Mussolini during his various terms as Italian Prime Minister (1994, 2001, 2008)? The arrival in his first government in 1994 of five ministers from the Italian Social Movement was only one of the steps leading to a broadening of the horizon of political legitimacy of a party that was the direct heir of fascism.

Silvio Berlusconi has been the victorious paladin of a black tide in a country where fascism has never disappeared and because it has been inscribed little by little on the social, political, cultural, mental territory of Italy, so that it has “inserted itself in the brutally selfish entrails” of its society. A miasmatic fascism, in a way, exhaling the stale air (la mal aria) of a culture that survived the regime set up by Mussolini.[9] Dr. Frankenstein-Berlusconi succeeded in bringing together in 1994 Gianfranco Fini’s Italian Social Movement (MSI), the oldest neo-fascist organization in Europe, and Umberto Bossi’s Lega Nord, a movement with a heightened identity-based regionalism that has been growing in influence since the early 1980s; in 2000, to unite all the right-wing parties in the Casa delle Libertà (House of Liberties), and then for a time in 2009 to merge the heirs of the MSI and the conservative right in a single Popolo della libertà (People of Liberty).

Berlusconi’s style was a successful form of “hybridization” that combined “old traditions with the new modernizing thrusts of the previous decade.”[10] Based on both the search for “active popular consent” and coercion (the subsequent restriction and repression of collective freedoms), berlusconism mobilized a strong cultural apparatus of ideological legitimization that succeeded in imposing its political hegemony. It relied on a particularly effective network of public (the three RAI channels) and private (the three channels owned by Silvio Berlusconi, Canale 5, Rete 4, Italia Uno) television channels, daily newspapers (such as Il Giornale, Il Foglio, Libero) and magazines. These increasingly important instruments were combined with the crisis of legitimacy of traditional political organizations caught up in the turmoil of Tangentopoli bribery scandals, process that was going to accelerate the phenomena of distancing from the social and cultural traditions to which the population was attached until then, but also from the social bonds to which it could lean and refer to.

Historical revisionism accompanied the Berlusconi regrouping ever more surely. So much so that in 2003, Fabrizio Cicchitto, a former deputy of the Socialist Party, maintained that La Casa delle libertà was “placed in the current of historical revisionism.” Anti-Communism and with it anti-antifascism constituted the ideological cement, but also what Francesco Biscione defined that same year as the “sommerso della Repubblica“, that is, the persistence of a reactionary anti-democratic culture, the real breeding ground of the Berlusconi coalition. To this historiographical offensive were added the repertoires of political action mobilized by the right to erase from memory and history “the misdeeds and infamies of fascism.” In Silvio Berlusconi’s country, the public and political use of history has never been so “unscrupulous/” Constantly seeking to oppose anti-fascism and democracy; where democracy becomes synonymous with liberalism and where the boundaries of anti-democracy extend to everything that cannot be associated with the liberal vision of the world. Thus, as the historian Pier Paolo Poggi pointed out, the “point of connection between revisionism and the dominant political cultures […] is precisely in the judgment on capitalism” and the depoliticization necessary for “the enslavement of billions of human beings.”[11]

The discourse of this right was and remains poor, but effective. It values civil society as a whole, as the only filter for “protecting the national community,” which it places above and beyond class divisions and, above all, the “defects” imputed to representative democracy.[12] This political culture was consistent with its own objectives: to overcome the legacy of the Welfare State, to impose anti-social policies, but also to make any prospect of social emancipation infinitely more difficult.[13] The apparent “victory” of this new right cannot be understood without the rift opened by the crisis of the left and the effective support of a part of it to Berlusconi.[14] The reorganization of the political field on the left began the presentation of a governmental “alternative,” at first social-democratic (of the Democratic Party of the Left, from 1991, of the Democrats of the Left, from 1998), and then purely democratic (of the Democratic Party – DP, from 2007, born of the merger of former members of the Democrats of the Left and Romano Prodi’s Catholics). After 2014, Matteo Renzi’s DP closed the cycle; the demolisher embodied in Italy at that moment the “capitalist realism” of which Mark Fisher spoke, that realism that presented neoliberal capitalism as the only possible option.[15]

Pretending to get rid of the “scoriae,” the dross, of the totalitarianisms of the 20th century, the post-communist intellectuals abandoned to the general condemnation what they considered from now on, at best as “the past of an illusion” (François Furet), at worst as a too cumbersome heritage. This process was accompanied by the blacklisting of Marxist historians. The parliamentary left has thus shown itself to be open to a rereading of the past, in particular of the period of resistance and anti-fascism, calling for the creation of a “shared memory,” which was the basis of the legitimacy of the alternation of governments of the two political poles that competed for power between 1994 and 2018.

But the so-called radical left too has at least in part, followed these interpretations. Fausto Bertinotti, leader of Rifondazione comunista (Communist Refoundation), the only party of the radical left to have a national audience in the early 2000s, also gave in to this “post-antifascist” ideology in his own way, valuing, in a letter to the editor of Corriere della Sera, “non-violence” as “an essential condition for bringing to life to the end all the radicality of this process of social transformation that we call communism.”[16] The Resistance as well as the revolution were thus returned to a “useful experience in order not to repeat the past mistakes”. The great cultural revision of the plural right has been deeply inscribed in the Italian subsoil, all the more surely because it has been at least partly accompanied by the renunciation of the left to its history. Berlusconism has integrated all spheres of society, even without Berlusconi himself or his party. “I am not afraid of Berlusconi in himself, but of Berlusconi in me,” the singer, composer, actor and playwright Giorgio Gaber summed up in his own way shortly before his death.

The suicide of the Republic, a daily practice?

This sense of the crisis of Italian politics is hardly new. It has been repeated at regular intervals since the early 1990s and the collapse of the Italian political system, caught up in the turmoil of the “clean hands” [Mani pulite] judicial machine, against the backdrop of an economic and social crisis. This tsunami gave rise to several new forces, or those presented as such, all of which collaborated, each in their own way, in the deepening of inequalities and the destruction of fundamental social rights. Their legitimacy has been eroded by alternating political administrations, marked by an inability to respond to the most pressing needs and by an almost assumed corruption which, as the Italian Communist Antonio Gramsci wrote, is “characteristic of certain situations in which the exercise of the hegemonic function [the necessary balance to be struck between consent and force] is difficult, the use of force presenting too many dangers;”[17] this is particularly the case for Forza Italia and the PD, the two forces that the ex-communist and former Democratic Council President Massimo D’Alema referred to, on April 10, 2018, as the “pillars of Italian bipolarism” “expression of the two great European political families.”[18]

This irresistible erosion of the new deal of the early 1990s, the time of a generation, has been coupled with the more general failure of politics, which in Italy has taken radical forms unknown elsewhere.[19] Consider the fact that since the beginning of the 21st centurye, the executive branch has been managed five times by highhanded “Princes”, as the French say, in this case by the two successive Presidents of the Republic (Giorgio Napolitano and Sergio Mattarella): Mario Monti’s “technical” government in November 2011, replacing a resigned Silvio Berlusconi; Enrico Letta’s, in April 2013, after the February elections in which no clear majority had emerged from the polls; Matteo Renzi, in February 2014, after the latter, who had become secretary of the Democratic Party, had pushed out Enrico Letta; Paolo Gentiloni, replacing Matteo Renzi, on the evening of December 4, 2016, after the resounding failure of the referendum for the revision of the Italian Constitution, for which he had worked hard; and finally Mario Draghi in February 2021. In particular, it is the “technical” governments of Mario Monti and Mario Draghi that have substituted the deliberative function of parliament for that of the choices of their executive, presented as “above” the parties. Parliaments in a state of war which, under the guise of a “financial” and/or “health” emergency, have agreed to abandon most of their prerogatives and to impose real structural shocks on the population.

As journalist Carlo Formenti notes, the economic and social crisis that had begun in 2008 was becoming an “instrument of capital aimed at disarticulating the subaltern classes and destroying their capacity for resistance.”[20] In 2012, a balanced budget was enshrined in the Italian Constitution (art. 81) with the support of the Democratic Party; Spain had done the same a few months earlier. Stefano Rodotà, professor emeritus of law, ironically stated at the time that this decision sanctioned “Keynes’ unconstitutionality.[21] The working classes bore the brunt of the austerity programs, with cuts to pensions, welfare, health, culture, education and so on. Not to mention the quality of life related to climate change and the demonstrated inability to deal with it with real public catastrophes (fires, floods, earthquakes) as more than 40 million people, two thirds of the total population, now live in dangerous areas.

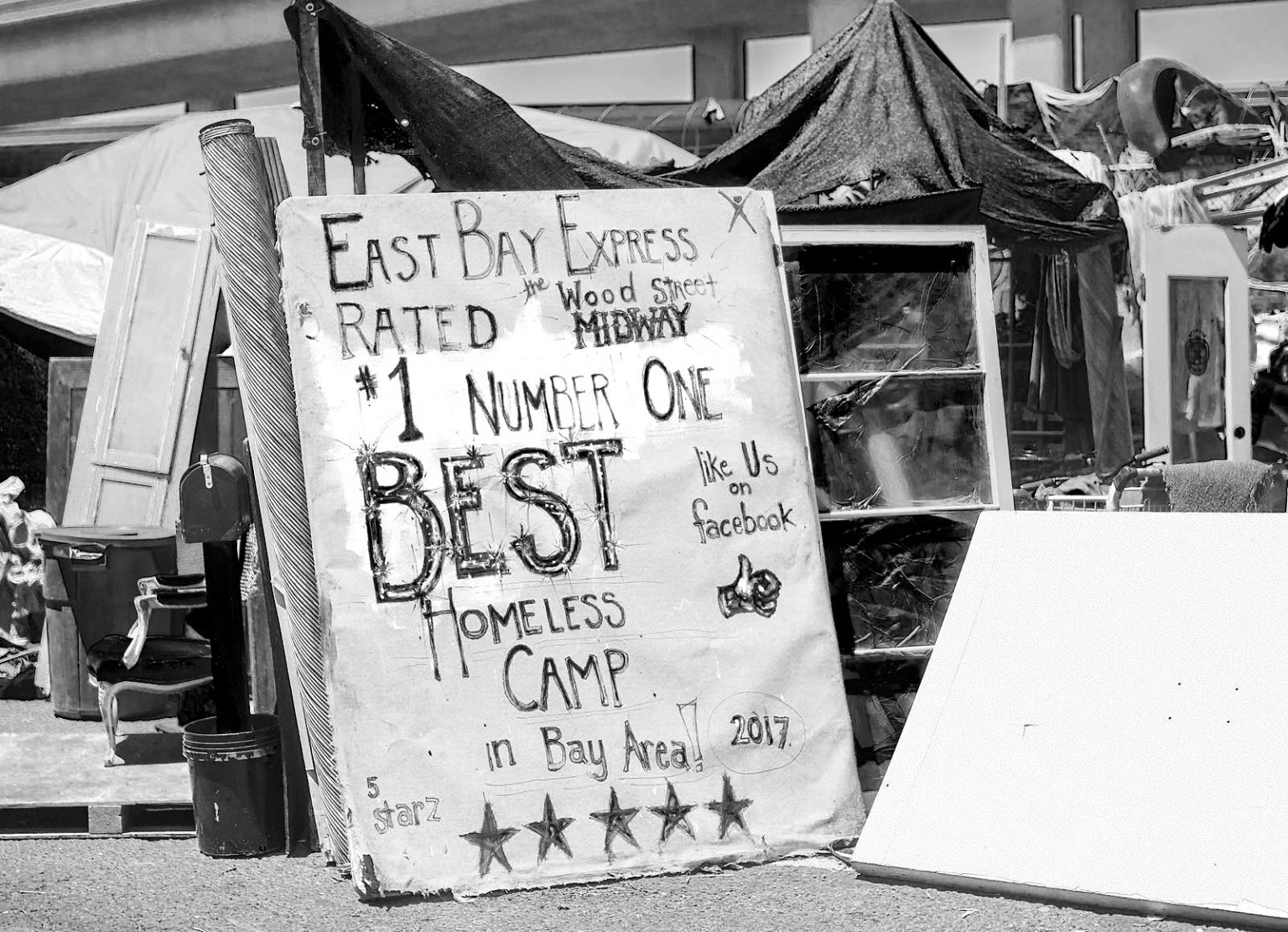

The “withdrawal of the working classes from the political exchange” has become an objective in order to impose a “reaggregated bourgeois bloc.”[22] And the increasing abstention is the most convincing indication of this. The number of voters has fallen by 3.7 million in ten years. Abstention rose from 19.5% in 2008, to 24.8% in 2013 and 27.1% in 2018, higher in the South than in the North (in Naples, 60.51% don’t vote).[23] It is estimated that in the next elections only about two of eligible voters will cast a ballot.[24]

The chain of economic crises has relentlessly worsened the living and working conditions of wage earners, transforming little by little, but no less surely, the political horizon and the social legitimacy of the struggle. The backlash against the simple idea that one can organize to fight injustice, seems all the more essential because it has been accompanied by “a dynamic of constant adaptation to the worst,” linked as much to a kind of “trivialization of injustice” as to a form of deterioration of the relationship of Italians to the state. At the mercy of alienation and exploitation, workers have gone from being a class capable of thinking of themselves as the engine of social change to a “phantom class,” singled out by the Italian political sphere.[25] To paraphrase Princeton political scientist Wendy Brown, neoliberalism has masked and depoliticized the reproduction of inequality, the “deproletarianization” of wage earners to “get them to embrace the ways of thinking and behaving of entrepreneurs;” the concomitant stigmatization of “foreigners” and the unemployed serving as a diversion from the rising anger. [26]

This dark framework has produced resentment and anger. The Italian population’s relationship of trust with its own political institutions (state, parliament, parties) has been severely shaken. Distrust of politics has been coupled with a crisis of confidence in the state and in the instruments of mediation. Consider the fact that, according to a survey published in La Repubblica in December 2011, trust in the state stood at 29.6%, in the parties at about 3.9% and in parliament at 8.5%.[27] Today, after two years of the pandemic these figures have increased significantly but remain relatively low (State, + 7%; parties + 9%; parliament + 14%).[28] Popular contempt for the “political class” is certainly linked to the latter’s powerlessness to confront the crisis. But it must also, and perhaps above all, be linked to the growing feeling of “disempowerment” and a loss of control by the population over decisions on which it no longer seems able to act, while the parties represented in parliament seem to have been content to raise the white flag by admitting their total incompetence. A clown provided the alternative.

Que se vayan todos! Away with all of them!

Beppe Grillo and his 5-Star Movement (M5) will for a time ride this Trojan horse and fill the void of representation in Italy by permanently drying up the potentialities of a left to be rebuilt. The movement that took shape in 2009 under the name of the 5-Star Movement (M5S) was initially built on the extraordinary popularity of the Genoa-based comedian. The son of a small businessman from Genoa was discovered by the star presenter, Pippo Baudo, at the end of the 1970s, who opened the doors of the flagship RAI program, Fantastico. But it was the collaboration with Antonio Ricci that made Grillo popular with the show Te la do io l’America [I’ll give you some of America], broadcast on RAI in 1983. The same Ricci would soon frequent the court of Silvio Berlusconi and create, in 1988, the Berlusconian show par excellence, Striscia la notizia (still on the air), a comedy news show with naked women and a deus ex machina embodied by a large red stuffed animal named Gabibbo, the standard-bearer of what he called “popular feelings” and whom he compared in December 2018 to Matteo Salvini.[29] Antonio Ricci invented the television language of Berlusconism. His objective: to conquer the audience, which he did for more than thirty years with empty phrases: “I don’t give a damn,” he said, “about satire, whether or not it pleases people like me, the intelligent and the cultured. What interests me is to capture the attention of Mrs. Pina at 08:30 PM.”[30]

Beppe Grillo knew how to surround himself with personalities with a strong cultural capital of sympathy from Michele Serra (journalist and columnist of the Repubblica) to Giorgio Gaber, through Antonio Ricci and Dario Fo; he recovered fragments of collective identity that he rearranged as needed.

The Genovese comedian turned his satire into a major political lever. In 2005, Time defined him as “seriously funny” and listed him among the 37 “European Heroes” who are “changing the world for the better.” Time noted in particular his role in exposing the Italian food giant Parmalat, the largest bankruptcy in Europe before the 2008 earthquake. Grillo entered hundreds of thousands of Italian homes through Striscia la notizia. The role of “comic vigilante” was made all the easier by the fact that he had constructed and disseminated a deceptive narrative of his own life, evoking a supposed banishment by the media after denouncing, in November 1986, on Fantastico, the corruption of the Socialist Party and of Bettino Craxi as head of the government. In 1988 he was back on RAI and in 1993 he had his own show in two parts, the Beppe Grillo show. In front of an audience disoriented by the Tangentopoli corruption scandals, he would pronounce his catchphrase: “I don’t know what’s happening, reality exceeds fiction”: his audience was the same one that, a few months later, would vote for Silvio Berlusconi for the first time.

Beppe Grillo can be considered a perfect product of Berlusconism. In the early 2000s, he became the spokesman for the anti-political protest that Silvio Berlusconi had embodied a decade earlier. What changed was his embodiment of the rupture, of a newness that was thought of here and now, without any future or distant horizon of reference. And just like his best enemy, the discourse he carried associated the disarticulation of the social link and expressed the absolute novelty in the Italian political field. He called for an end to professional politicians and all forms of social mediation (as unions), at a time when Sergio Rizzo and Gian Antonio Stella, two journalists from the Corriere della sera, that is, the daily newspaper par excellence of Italian entrepreneurship, were sending back to the whole of Italy the image of a political class that was no longer at the service of the national community and the common good, but of its own interests. Their book, entitled La Casta, would be a landmark; the subtitle is quite telling: “This is how the political class became untouchable”[31]

The book was published on May 2, 2007; four months later, on September 8, Beppe Grillo launched the first V[affanculo] Day [Fuck off-Day], where he announced the death of political parties. Exacerbating the image of the sublimated relationship of the leader with his people, he proposed himself as the “only possibility of reality,” in a period in which the DP was completing its transformation, at the service of “virtuous” economic policies of public debt reduction, becoming the party of the “right-wing,” the other right-wing, the party of the modernist bourgeoisie. The abandonment of its electoral base, especially public sector employees and students, was coupled with a deeper renunciation of the very ideas of justice and equality. This adaptation to the existing order ended up permanently blurring the classic political categorizations in which the new generations no longer recognized themselves. The left has been reduced more and more to the group of those who thought they belonged to it, but without necessarily sharing its fundamental values. Certainly, at about the same time, the metamorphosis affecting the DP was taking place among other parties throughout Europe. However, its precursory status was accompanied here by an unparalleled extremism, the impact of which was particularly devastating, including for the radical left, which has also become disjointed, frayed, decomposed, “evaporated,”, swept away by the ebb tide.

Faced with the disaster of a left that was incapable of shaping a horizon for the anger that was rising, Beppe Grillo and his movement were to impose themselves as the only “alternative subject.” In fact, the appearance on the Italian political scene of the Genoese comedian has, at the same time, captured to his advantage the social sphere of indignation in the immense void left by the left and blocked the experiences of the type that were to spread all over the world (Indignados, Occupy, Fearless Cities, etc.) and their political incarnations (Podemos, Syriza, etc.).[32] The political, social, economic and moral crises that the Peninsula went through in the 2000s gave the movement the oxygen it needed. In Italy, the formula of the Argentinean demonstrators “que se vayan todos” was stripped of its insurrectionary force.

The chalice of death

Umberto Bossi’s Lega had succeeded in disarticulating Christian Democracy, in difficulty in its main strongholds, gaining a lasting foothold in the so-called “white zone” or Catholic and conservative areas of the peninsula, where the Christian Democracy vote was, until the 1980s, a vote “for the Church and against Communism.”[33] In this sense, it played a key role in consolidating the right-wing constellation that emerged in the early 1990s. This is the same path that Beppe Grillo and his movement took. After all, wasn’t it precisely Umberto Bossi’s party that Gianroberto Casaleggio, Grillo’s mentor and creator of the BeppeGrillo.it blog in 2005, had decided to emulate? This time, however, it was the so-called red zones, the former bastions of the Communist Party, that were their favorite terrain, dislocating, dispossessing and finally dismissing what was left of the values, history and memory of the left, in particular that of anti-fascism.

Thus Beppe Grillo chose September 8, 2007 to launch his first “Vaffanculo Day,” a date with a high symbolic value in the Italian history of the 20th century and in particular in the history of fascism. Indeed, on September 8, 1943, Marshal Pietro Badoglio announced the signing of the armistice with the Allies. On that date, the king and the government fled the capital, leaving behind a disoriented population at the mercy of the German troops that had poured into the country since the dismissal of Benito Mussolini 45 days earlier. “Tutti a casa” [everyone home] seemed to be the confused motto of that day, well rendered by Luigi Comencini’s eponymous film. This Vaffanculo Day (V-Day) is the culmination of the thousands of “Vaffanculo” (Fuck you!) that Grillo had shouted on all the stages, big and small, of Italy. Like the one at the Smeraldo theater in Milan, where in 1992 he announced the birth of “gentocracy”, invoking the seizure of power by the mood of the people and their anger; people who “are no longer afraid to say what they think […]”.[34] “La gente“, a singular subject in Italian, whose plural declension in English (the people) renders well the idea of an entity that disintegrates into an “ego-governing” multitude of individuals.[35] “Gentism”, thought of as the “ultimate evolution of the old notion of people” referred to the indistinct and interchangeable public, which in the language of the future M5S will become “one is one,” a horizontality that leads precisely to the opposite of the declared objectives of direct democracy, that is to say, to the denial of the collective through the fragmentation of opinions and to the place ultimately left to the broad prerogatives of the “leader.”

While the V-Day mobilizations took place in more than 180 Italian cities, including outside the country, it was in Bologna, in the heart of the so-called red zone, that Beppe Grillo chose to take the floor, challenging the left, or better, seeking to erase its memory. In front of tens of thousands of people, Beppe Grillo was going to tell the politicians to go home with a unique cry: “Vaffa…” [Screw you…] to “the caste”: “Italians, September 8 has arrived, the day of our defeat; this September 8 will be the day of their defeat. V-Day, as in Vaffanculo Day.” By making September 8, the day of the defeat of Mussolini’s war, the day of the defeat of the public he was addressing, Beppe Grillo reappropriated the revisionist re-readings of Italian fascism of the 1990s, including the concept of “death of the nation,” applied by revisionism precisely to September 8, 1943, that rendered illegitimate the parties that had emerged from the War of Resistance.

On that occasion, the comedian announced that he wanted to “take back the country” by organizing a movement of the “bourgeois” and the “conservatives.”[36] A year later, Beppe Grillo was to take over the 25th of April, the high place of memory of the Italian Resistance, organizing new rallies in more than 400 cities, shouting “we are the real partisans.” And it was in Turin, the flagship city of the workers’ movement, the “Italian Petrograd,” the city of Antonio Gramsci and the Factory Councils, the epicenter of the 1917 and 1945 insurrection, that he decided to speak. This time, it was to promote a referendum on the abolition of public funding for the press; a hard blow in particular for the non-aligned media, those of the radical left, and a welcome boost to those who, like Gianroberto Casaleggio, were making their money on the Web.

Beppe Grillo has actively sought to erase the memory of the struggles of the oppressed by confiscating space on the left, a left that he defines as “much worse” than the right, while claiming to be “neither left nor right, but on the side of the citizens.”[37] The movement set in motion at the time, which two years later was to become the 5-Star Movement (M5S), was not configured as a movement that promoted awareness of oneself, of others and of the group formed with others through battles fought collectively. For during the V-Days, it was not the square “place of protest and conflict” that was at the center, but Beppe Grillo, and in Bologna as in Turin and other Italian cities, it was not demonstrators who gathered, but spectators. The participation was limited to the “Vaffa…” repeated in chorus accompanied by the gestures of a “multitude” that, instead of the raised fist, symbolizing the collective struggles for human emancipation, raised the middle finger. An unbearable nose-thumbing to this idea, in the heart of the mobilizations of the years 1968, sung in 1972 by Giorgio Gaber: “The freedom, it is not to remain on a tree, it is not either the flight of a fly, the freedom it is not an empty space, the freedom it is the participation.”[38]

The “Vaffa” will function as a connector that seeks both to arouse emotion and to play on a set of confused feelings, a tangible link between these “diverse elements” in the same way as the graphic of the V of MoVimento, borrowed from the film by James McTeigue, V for Vendetta, with its composite cultural character, or the “courage” of M5S in choosing the color yellow, a color “carefully avoided in the political world” because it is that of “lies, hypocrisy, betrayal.”[39] With the crisis of 2008, Grillo became the spokesperson for a new form of political organization, “light and powerful.”[40] A movement that combined the energy of the Web to mobilize, which could compare with the political parties of the Golden Years of Capitalism, and the channel of dissemination of the small screen, an instrument favored by Silvio Berlusconi and on which Grillo made his debut. The Web was the major card of this device.[41] In 2009, the blog BeppeGrillo.it was ranked seventh among the twenty-five most popular in the world by Forbes and, in the same period, it was among the ten most influential on the planet according to The Guardian. At that time, 53% of households in Italy had access to the Internet (compared to 66% at the European level), a rate that would only increase over time to reach 84% ten years later. The success of the blog and the following of it were linked to the almost total monopolization of the television channels by Silvio Berlusconi, who was in government at the time. The blog was meant to be “an alternative to the ‘classic’ information.”[42] “Beppe does a real journalistic job of synthesis,” said one of his followers, “it would be so tiring to go and look for all the information he gives us”[43] .

The blog became the vector of what Robert Proctor called a “culturally produced ignorance,” using doubt as the privileged weapon of his “agnotology,” that is, his agnosticism, and the construction of parallel realities.[44] Grillo claimed, for example, that AIDS was the “greatest intoxicant of the century” or that cancer prevention campaigns were dangerous. In 2019, he even announced his participation in the congress of those who believe that the earth is flat.[45] The blog made use of fakes (users with false identities who directed the discussion), trolls (users who intervened to provoke the interlocutors) and influencers (users who influenced others).”[46] A practice adopted by groups of the M5S or close to the M5S, some of which promoted campaigns of “media lynching” and threats. Grillo’s blog also spread the themes dear to the Greens, in the wave of the huge mobilization against the privatization of water, by “putting environmental issues at the heart of the indictment against capitalist companies,” while publicizing, for example, the use of Biowashball, a ball produced in Switzerland that would supposedly make detergents superfluous.[47]

Very quickly, journalists, all journalists, became the object of invective, going so far as to ban them from the meetings of the movement, including that of Piazza San Giovanni in Rome, at the end of the “Tsunami tour” for the national elections of February 2013. In 2017, Beppe Grillo even went so far as to call for the establishment of a “people’s jury” against newspapers and TV newscasts that publish fakenews, in a country that at that time was in 77th place in terms of press freedom.[48]

Refusing the left-right divide, in the same way as Umberto Bossi before him, Beppe Grillo has been able to constitute a sort of appeal for a growing fringe of the population. He initially drew on the broad opposition to Berlusconi, capturing, rearranging, disarticulating, and emptying a vocabulary proper to the left, attracting to him some of the leading figures of its intellectuals (Erri de Luca, Dario Fo…), and then enlarging his mass base, taking advantage of the decomposition of the Italian political field and blood-sucking of Berlusconism, “an unprecedented form of destruction of democracy.”[49] “We have managed,” Beppe Grillo said during the closing meeting of the national elections of March 2018, “to accelerate and annihilate all the parties, which have dissolved into a kind of nauseating surface […] the only real party that exists today in Italy is ours.” Parties that he described as “zombies,” “the living dead,” and “walking coffins,” to which the M5S was to become, according to Gianroberto Casaleggio, “the amanita phalloides” poison mushroom.

Winter is coming

The M5S has long simmered in the bowels of the country, as demonstrated by its rapid electoral victories, inserting itself into the territories and organizing itself at the local level. It has its roots in the depths of the Italian subsoil, in the “sovversivismo” that Antonio Gramsci wrote about, “the ‘subversive’ character [sovversivismo] of these layers has two faces: one turned to the left, the other to the right, but the left figure is just a feint; they always go to the right in decisive moments and their desperate ‘courage’ always prefers to have the carabinieri as allies.” And it is indeed the right and the extreme right (the Lega, Casapound, the southern extreme right) that appeared as the shore to which this ideology of non-ideology had attached itself durably, while actively feeding the lure of an alternative “left” formation. Thus the M5S has on occasion presented itself as a bulwark against the far right. On July 10, 2013, after being received by the President of the Republic Giorgio Napolitano, Beppe Grillo also let it be known in his own way: “[…] I went to the territories, and I’m angry because I’ve gathered the anger of those I met. […] I always try to moderate the spirits, I said it to the President of the Republic, what I say is something I experienced […]; we must moderate the spirits, the spirits of the people who want to arm themselves with guns, with sticks and who say that the revolution is done only like that and I say to them, calm down, let’s try again with the democratic methods […].”[50] But behind the invoked revolution, the suggested eversion and the distant echo of the “Bergamo guns” that the Lega Nord waved in the 1990s with the same rhetoric of an Umberto Bossi who then also claimed to have mastered the ardors of the base.[51] The M5S took also part in the common culture of the right based on the “cult of the leader, the disarticulation of intermediate organizations and an ideological eclecticism” what the historian Paul Ginsborg once called a mixture of charismatic, plebiscitary and traditionalist elements.

The M5S proved itself adept at “intercepting and interpreting every type of protest and uneasiness” and keeping them together. It has presented itself as a megaphone that gave strength and voice to the “feeling” (or resentment), to the “anger” of a population that, for more than thirty years, has suffered both the consequences of the economic, social and political crises experienced by the whole of Europe and the inversism (radical inversion of values) to which the great cultural revision of Berlusconism and the plural right has led. An inversism that can be seen, for example, in the positioning of the M5S spokespersons on fascism: “an ideology of the past” according to Beppe Grillo, who limited himself to saying that he is not a fascist; Luigi di Maio affirmed that, within the M5S, “there are those who refer to [Enrico] Berlinguer [an italian communist leader in the 1980s], the Christian Democratic Party or Almirante”. He defended the idea that “the categories of fascism and anti-fascism were only used to ‘instrumentalize’ [the debates], because no one deserves to be demonized, and it is possible that mistakes were made on both sides, but also that choices were made in good faith”. Another young leader at the time of the M5S, Alessandro di Battista, sententiously announced that “it is more important to be honest than anti-fascist.” A position that resonates with that of a growing part of the population. Beppe Grillo opened a dialogue with the neo-fascist movement CasaPound, or at least with its activists, and attracted to him men socialized in the Italian Social Movement, such as Luigi di Maio and Alessandro Di Battista, both sons of MSI militants. The father of the current Minister of Foreign Affairs, now outside the M5S, proudly admitted to having worked with Giorgio Almirante and Gianfranco Fini and said he found in the M5S the “values of the old right.”[52]

The rhetoric used by Beppe Grillo, under cover of humor, is that of the extreme right. The shift of the electoral base of the movement towards the positions of the Lega, in dialogue with the general orientations of the M5S embodied by Beppe Grillo, seems to confirm this. In 2008, didn’t he declare, “I’m not a politician…I could do it only in a small dictatorship where I would have the possibility of using a stadium to put the 80,000-100,000 people who are hurting Italy.” And in 2013, after the February elections, did he not say, “Let those who do not want to adhere to our rules say so immediately. Then we can stone them.”[53] In January 2017, when the European far right, on the rebound of the arrival of Donald Trump to the presidency of the United States, met in Koblenz, announced “the dawn of a New World” (Marine Le Pen) and the dream of a “new Europe” (Geert Wilders) hegemonized by their parties, Beppe Grillo announced in the French Journal du Dimanche: “International politics needs strong statesmen like them [Vladimir Putin and Donald Trump]. I see them as a benefit to humanity.”[54] Steve Bannon’s Alt-right site, Breitbart, was sure to welcome these words. Between 2012 and 2016, the propensity of M5S voters to vote for the right gradually increased. Thus, according to Delia Baldassari and Paolo Segatti, at the exit polls in March 2018, the preferred party of M5S voters after their own was Matteo Salvini’s.[55]

Beppe Grillo’s repeated attacks on the “self-righteous and angelic left” (buonista) concerning immigration policy or anti-racism was only one of the declensions of a new syncretism mixing indifferently the fight against migrants and the fight against corruption and mafias (“the illegal immigrant is useful,” he wrote, “to criminality”.)[56] Grillo and his M5S became the standard-bearers of the battle against a non-existent foreign invasion, supposedly endangering the security and wages of Italians, riding the racist Trojan horse without hesitation. The “gentism” that Grillo has championed since the distant 1990s referred to an “ethnic” people, as one of the leaders of Podemos, Íñigo Errejón, very ably pointed out,[57] and the M5S voters were not mistaken. Consider the fact that among those who voted for the M5S, the majority believed that “immigration is a threat to Italian cultural identity.”[58] Didn’t Grillo say that the Roma were a “time bomb” adding “before the borders of the Fatherland were sacred, the politicians desecrated them”? The Nation, Italy, the defense of the Homeland and Italians against migrants, occult powers or Europe, have been on the agenda since the structuring of the movement and this rhetoric has not changed since then, at most it has undergone tactical adaptations.

The M5S-Lega government from June 2018 to August 2019 attests to this. A government that sociologist Domenico Masi defined as the most right-wing in the history of republican Italy, that analyst Ezio Mauro called the “realized right,” and that journalist Claudio Tito described as a “practical laboratory of a new right” based on a “new social block.”[59] This executive passed a number of measures, including the citizenship income, today the “social” flagship of the M5S, which is attacked from all sides, but which is in fact a workfare, putting the most precarious people to work with the prohibition of refusing more than three jobs offered in two years; jobs that could be found within a 100 km radius for the first, 250 for the second and in the whole country for the third. The citizenship income was further restricted to Italians and immigrants with a long-term residence permit who have lived in Italy for more than ten years, leaving at the side of the road all those who arrived in Italy after 2012, at a time when the number of immigrants in Italy has increased by more than 43% compared to 2008, and who constitute the most vulnerable, precarious and poor segment of the population.[60]

The same government passed the “Decree on Security and Immigration,” defined today as a mistake by Giuseppe Conte, the new leader of the M5S and at the time nevertheless President of the Council, one of the most authoritarian and reactionary provisions in the entire history of republican Italy, amended in 2020. It provided for the abolition of the residence permit for humanitarian reasons, the doubling of the number of days of detention in the administrative centers set up for this purpose (Permanent Return Center (Cpr), the impossibility for asylum seekers to be registered in the civil registry and therefore to have access to the right of residence. In terms of “security”, the decree authorized the use of tasers in municipalities with more than 100,000 inhabitants and heavier penalties, up to two years in prison, for those who promote the occupation of land or buildings. The government led by Matteo Salvini and Luigi di Maio has made the fight against the poor and migrants its political priority. While racially motivated violence has continued to increase throughout the peninsula (an increase that Luigi di Maio loudly denied), the Lega-5-Star government has chosen to criminalize solidarity and facilitate the legal possession of firearms, including Kalashnikovs.

This governmental experiment lasted 14 months. In August 2019, Matteo Salvini opened a crisis within the government calling for immediate elections; frightened by this prospect after the Lega’s victory in the European elections in May, the 5-Star Movement and the Democratic Party established a new alliance, headed by… the same Giuseppe Conte. Moreover, there was no difference in nature with the neo-liberal policies pursued until then by the DP and the right wing allied with the extreme right, only the degree of difference in terms of job insecurity and restrictions on migration. The establishment of the M5S-PD government in September 2019 and the support of the M5S to the government headed by Mario Draghi in February 2021, in the midst of a health crisis, is the masterful confirmation of this.

The French sociologist Éric Fassin proposed to interpret what he called the “populist moment” not as a reaction to neoliberalism, but as a way of guaranteeing its popular success.[61] The M5S was a product of neoliberalism, but also of the internalized neoliberal subjectivity that its practice implies. “Users” who asserted their individual “human capital” through a digitized “mass self-communication” that seems to be able to dispense with traditional mediations, while blurring the asymmetry of actors[62] . Where the Web and its tools were not considered as means to reach a digital direct democracy to be built and thought according to the potentialities that Internet effectively opened up, but as a political form already completed. This techno-utopia was based on the economic and cultural determinants of a neo-liberalism integrated by the subjectivity of the subjects, where horizontality and claimed participation are in contradiction with the necessary extreme centralization of a composite movement, on pain of implosion, as the last departures of the movement and the vertiginous losses in the voting intentions for the M5S seem to show.[63]

The neither “right or left” slogan about the M5S has functioned as a mantra that has prevented serious reflection on this unprecedented political phenomenon that has served as a conveyor belt for the political lexicon of the ultra-right. Grillo and his M5S have played on what Wendy Brown calls “class resentment without class consciousness.”[64] This resentment feeds back into the modalities of action and discourse of the M5S, which has blurred the mechanisms that reproduce, intensify and depoliticize inequalities, and thus has removed the capacity to react. Grillo and his M5S have advocated the disappearance of the instances that existed before to combat the forms of hatred, humiliation and subordination that the oppressed face, without proposing others. Using a novlanguage modelled on the Wikipedian npov (neutral point of view), emptying words of their content, inventing others, inverting or “obliterating their meaning [….] preventing us from thinking in different terms” and minimizing the attacks on the subalterns (the austerity cuts being restricted in Grillo’s language to frattaglie, slaughter/waste), reducing to nothing all possibilities of raising the level of class consciousness, which is the only way to counter them.[65] The M5S would be, in this perspective, a (post)modern right that comes from the war against the elites, from the permanent polemic against the State, from the refusal of political correctness.[66]

Not only did the M5S and its leaders agitate signifiers that are now hollow (direct democracy, freedom…), but also what the historian Furio Jesi, inspired by Oswald Spengler, called “ideas without words” characteristic of the culture of the right, or to be more precise, “spiritualized words” “that pretend to be able to really say and therefore to say and at the same time to hide in the secret sphere of the symbol”; terms that are supposed to conceal a shared “secret”, but that do not need to be explained and that, through their use, become a vector of ideas without words and thus found the present and future solidity of the community to which they intend to address.[67] The vote for the M5S had no “social roots”; it was carried by “ideas without words.” It wasa base that comes close to what Luigi Salvatorelli, a liberal antifascist, called in 1922, the fifth state, indicating a new category that “does not coincide with the socially and politically defined proletariat”, the fodder of a new form of revolt that seeks ways out.[68]

The M5S could be identified with a chemical catalyst. Beppe Grillo vouched for the biodegradable nature of his movement, indicating that it could be converted into a simple molecule that could be used by the new politics that it would have helped to create by producing the decomposition of the old[69] .

The eternal “return” of fascism

It is not uncommon in recent weeks to see references to a speech given by Umberto Eco at Columbia University on 25 April 1995. Entitled “Eternal Fascism,” it was given in the aftermath of the right-wing bombing that struck Oklahoma City, leaving several hundred people injured and dozens dead. Reflecting afresh on the persistence of fascism, its forms and its evolution over time, it seemed beyond the celebration of the fiftieth anniversary of the Italian liberation, to be an urgent necessity. The text emphasized the still very real risks that the (re)birth of fascism posed to the world: “It would be so much easier, for us,” wrote Umberto Eco, “if there appeared on the world scene somebody saying: ‘I want to reopen Auschwitz, I want the Black Shirts to parade again in the Italian squares’. Life is not that simple. Ur fascism [eternal fascism] can come bac under the most innocent of disguise. Our duty is to uncover it and to point our finger at any of its new instances – every day, in every part of the world.”[70] This same lecture was republished just a few months before the March 2018 elections when the threatening presence of Matteo Salvini in the ranks of the right-wing coalition reactivated fears of a return of fascism. Giorgia Meloni and her party now seem to be closing the cycle of this creeping counter-revolution started some 30 years ago and in the political and cultural acceleration of which the M5S played a crucial role. n the meantime, Italy has been at the forefront of a global health crisis, counting its tens of thousands of deaths; an exsanguinated, politically unstable, socially torn Italy. One of the most fragile economies of the Eurozone, hit in the heart, where the containment measures have generated a global recession, unprecedented in historical magnitude and spread.

Fascist? Many terms are used to describe the right wing facing the doors of power today, hypnotizing the public debate, looking for words “to designate the family of dangerous demagogues.”[71] Their very overabundance refers to the difficulty of determining its new contours: fascist or post-fascist, to point out the continuity in its transformation; populist, to mark the novelty of a phenomenon born in the second part of the 20th century, designating (or not) a link of continuity with the fascism of the interwar period.[72] There is no doubt that FdI is the real thing, whatever the international press may have thought after the release of a video in three languages where Giorgia Meloni would have “abjured” fascism, but where however she addressed the problem of the legacy of fascism in one sentence and targeted mainly antifascism, communism and the left. And yet, those who wave the danger of fascism today fail to be heard by the majority of Italians, because it has too often been used to push the population to vote for the “lesser evil”, even while holding their noses, according to the formula used by Matteo Renzi during the 2018 election campaign. Serious mistakes have been made by anti-fascists, who thinking that calling anyone a fascist (Bossi, Salvini, Berlusconi, Grillo himself, etc.) was enough to disqualify them in front of the electorate. While they failed to grasp the new dimensions of fascism and the need to fight them as such.But also because the destruction of the past, that is to say, of the ties that bind contemporaries to previous generations has been here, more than elsewhere, brought forward with special diligence in the last thirty years.

It is a country that recently saw a journalist from the daily newspaper La Stampa threatened because of a report dedicated to the nostalgia for fascism. A country where on October 9, 2021, the national headquarters of the largest Italian trade union was attacked and devastated by so-called No Vax groups. A country where a daily newspaper like Il Giornale was able to distribute Mein Kampf in the 1938 Italian translation as a gift to its readers.[73] A country that for decades has criminalized anti-fascism, that eternal “troublemaker” of a repressive political and social order, singled out as the only “real danger to Italian democracy.” Ernesto Galli della Loggia, an editorial writer for the daily Corriere della Sera, who often begins his editorials with “those who have read a few books”, which is supposed to give him unquestionable legitimacy, sums up this political position in one sentence: “If fascism is violence, illegality and the suppression of liberty, its antithesis is not anti-fascism, but democracy.”[74] And yet “where the dikes of anti-fascism have broken, racial hatred spreads.”[75] As on February 3, 2018 in Macerata (Marche), Luca Traini, former unsuccessful candidate of the Lega and former member of the order service of its leader, shot six people from sub-Saharan Africa; when, two hours later, the police arrested him, Luca Traini, wrapped in the Italian flag, shouted, “Long live Italy!” while making the fascist salute. After this attack everyone, from the FDI to the DP, accused the migrants of being responsible for this violence.

“Italy is a circular country,” wrote Pier Paolo Pasolini in his privateer writings, “like the Leopard of Lampedusa, in which everything changes in order to remain as it was before,” because, he continued, “it is a country without memory which, if it had any care for its history, would know that ‘regimes carry ancient poisons, invincible metastases.” [76] This country mired in a complex of economic, political, social, ecological and moral crises, which add up and combine, seems to be living at the time of the return of one of those interregnum in which “arise the most varied morbid phenomena” (Gramsci). All the more so because it has forgotten the meaning of history, of the oppressed and their struggles, because it sinks into a culturally produced ignorance for decades and because it seems to have exhausted all forms of discernment. The irrationality of capitalism has ended up undermining its traditional formations; the elementary democratic principles are eroded and the escape from freedom (Erich Fromm) seems to impose itself. The splintering of the social being is then masked by the appeal to the “people” against the “powerful”, tending to neutralize the capacity to become conscious of oneself, of the others and of the multiple collective dimensions of our humanity, and to reject the phenomena of contestation in a pre-political universe in the manner of what Gramsci defined as apolitism, which is expressed in “phrases of rebellion [ribellismo], of subversivism [sovversivismo], of primitive and elementary anti-statism”[77] Something like the “late fascism” pointed out by the philosopher Alberto Toscano.[78] Whatever the outcome of the next elections, a change of era is underway. Italy year zero…

Notes:

[1] Nikou Asgari and Ian Johnston, “Italy long-term borrowing costs stuck near eight-years high”, Financial Times, 28 July 2022.

[2] Amy Kazmin, “Doubts over Italy’s access to €800bn EU Covid fund after Mario Draghi’s exit”, FT, 6 August 2022

[3] Amy Kazmin, “Doubts over Italy’s access to €800bn EU Covid fund after Mario Draghi’s exit”, FT, 6 August 2022

[4] ISTAT, Le statistiche dell’ISTAT sulla povertà. Anno 2021, June 2022 (https://www.istat.it/it/files/2022/06/Report_Povertà_2021_14-06.pdf).

[5] Lobby nera, Fanpage, September 30, 2021 (https://youmedia.fanpage.it/video/al/YVXPpOSwUXALhewA).

[6] For 2018 results, Il Sole 24 ore, March 23, 2018; for 2013 results, http://elezionistorico.interno.gov.it/

[7] Ilvo Diamanti, Gli Italiani e lo Stato. Rapporto 2017 (demos.it).

[8] Ilvo Diamanti, Rapporto gli Italiani e lo Stato 2021 (demos.it).

[9] Giovanni Valenti, “Un “Cavaliere nero” per gli orfani del regime”, La Repubblica, 24 November 1993.

[10] Rino Genovese, Che cos’è il berlusconismo, Rome, Manifestolibri, 2011.

[11] Pier Paolo Poggi, Nazismo e revisionismo storico, Rome, Manifesto libri, 1997, p. 112.

[12] Carlo Ruzza, “Italy: the political right and concepts of civil society,” Journal of Political Ideologies, No. 15, 2010, p. 264.

[13] Geoff, Eley, “Legacies of Antifascism: constructing democracy in Postwar Europe,” New German Critique, No. 67, Winter 1996, pp. 73-100.

[14] Perry Anderson, “An invertebrate left. Italy’s Squandered Heritage,” London Review of Books, vol. 13, N°5, March 2009.

[15] Mark Fisher, “How to kill a Zombie: strategizing the end of neoliberalism,” Opendemocracy.net, July 18, 2013.

[16] Fausto Bertinotti, “Rigettiamo il determinismo, pensiamo ad un processo aperto”, Corriere della Sera, 1e December 2003.

[17] Antonio Gramsci, “Note sulla vita nazionale francese”, Cahiers N°13, § (37).

[18] Massimo D’Alema, “Il voto italiano è il punto di rottura della crisi europea,” Il Manifesto, April 10, 2018.

[19] Marco Revelli, Finale di partito, Turin, Einaudi, 2013, p. IX.

[20] Carlo Formenti, La variante populista. La lotta di classe nel neoliberalismo, Rome, DeriveApprodi, 2016, p. 7.

[21] Stefano Rodotà, “Lo scippo della Costituzione,” La Repubblica, June 20, 2012. Adam Tooze, Crashed. How a decade of financial crisis changed the world, Paris, Belles Lettres, 2018 (ebook).

[22] Bruno Amable, Stefano Palombarini, L’illusion du bloc bourgeois. Alliances sociales et avenir du modèle français, Paris, Raison d’Agir, 2017, Paris, Raison d’Agir, 2017, p. 13.

[23] Il Manifesto, March 5, 2018

[24] Alessandra Ghisleri, “Verso il voto: FdI doppia la Lega, Azione supera FI. Un elettore su tre non ha deciso,” La Stampa, August 31, 2022.

[25] Loris Campetti, Ma come fanno gli operai. Precarietà, solitudine, sfruttamento. Reportage da una classe fantasma, San Cesario, Manni, 2018.

[26] Wendy Brown, « ”Rien n’est jamais achevé”. Un entretien avec Wendy Brown sur la subjectivité néolibérale », Terrains/Théories, N°6, 2017p. 1.

[27] Demos, “XIV Rapporto. Gli Italiani e lo Stato,” January 9, 2012 (demos.it).

[28] Demos, “XXIV. Rapporto. Gli Italiani e lo Stato”, December 2021 (demos.it).

[29] Aldo Cazzullo, “Antonio Ricci: “Salvini mi riccorda Gabibbo, Masterchef rovina le cene”, Corriere della Sera, December 2, 2018.

[30] Quoted in Giuliano Santoro, Breaking Beppe. Dal Grillo qualunque alla Guerra civile simulata, Rome, Castelvecchi, 2014.

[31] Sergio Rizzo, Gian Antonio Stella, La Casta. Così i politici italiani sono diventati intoccabili, Milan, Rizzoli, 2007.

[32] Benedetta Tobagi, “Queste nostre democrazie fragili,” La Repubblica, February 14, 2017.

[33] Martina Avanza, Les ” Pure et durs de Padanie “. Ethnographie du militantisme nationaliste de la Ligue du Nord (Italie), PhD thesis, Ecole des Hautes Etudes en Sciences Sociales, Paris, December 2007.

[34] Camillo Arcuri, “Voglio un pubblico col cartellino”, Corriere della Sera, 13 February 1992.

[35] Dany-Robert Dufour, “Vivre en troupeau en se pensant libres”, Le Monde diplomatique, N°646, January 2008.

[36] Giuliano Santoro, Breaking Beppe.

[37] “Questa sinistra peggio della destra”, La Stampa, 10 September 2007.

[38] Song from the album, Dialogo tra un impegnato e uno non so (1972).

[39] Catherine Calvet, « Michel Pastoureau : “Le jaune est la couleur des trompeurs mais aussi des trompés” », Libération, December 5, 2018.

[40] Paolo Gerbaudo, Il Partito piattaforma. La trasformazione dell’era politica nell’era digitale, Milan, Feltrinelli, 2018.

[41] John Hooper, “Italy’s web guru tastes power as new political movement goes viral,” The Guardian, January 3, 2013.

[42] Eurostat, “Households: level of Internet access,” January 31, 2019 (https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/digital-economy-and-society/data/database).

[43] Federica de Maria, Edoardo Fleischner, Emilio Targia, Chi ha paura di Beppe Grillo, Milan, Selene, 2008, p. 38.

[44] Robert Proctor, Londa Schiebinger (eds.), Agnotology. The Making and Unmaking of Ignorance, Standford University Press, 2008.

[45] Francesco Merlo, “C’era una volta Beppe Grillo,” la Repubblica, May 1, 2019.

[46] Carlo Vulpio, “La Rete è un trucco,” Corriere della Sera, July 1, 2012.

[47] Nadia Urbinati, “Mobilisations en réseaux, activisme numérique : les nouvelles attentes participatives”, Esprit, N°8, August-September 2013, p. 89.

[48] Reporters Without Borders ranking for the year 2016 (rsf.org).

[49] Paolo Flores d’Arcais, “Fascism and Berlusconism”, Le Débat, N°164, 2011, p. 10.

[50] “Beppe Grillo al Quirinale: conferenza stampa, 10/07/2013” (www.youtube.com); see also Rinaldo Vignati, “Dai comuni al Parlamento: il Movimento entra nelle istituzioni,” in Piergiorgio Corbetta (ed.), M5S. Come cambia il partito di Grillo.

[51] Stefano Marroni, “Avevo 300 mila ribelli”, La Repubblica, 30 August 1994.

[52] Corriere della Sera, February 13, 2018.

[53] Giuliano Santoro, Breaking Beppe.

[54] “Beppe Grillo: “Le bilan de l’Europe est un échec total” », Journal du Dimanche, January 22, 2017.

[55] Delia Baldassari, Paolo Segatti, “Ancora Sinistra-Destra”, in Itanes, Vox populi. Il voto ad alta voce del 2018, Bologne, Il Mulino, 2018

[56] Beppe Grillo, “Un clandestino è per sempre,” beppegrillo.it, May 1, 2011.

[57] Ludovic Lamant, « Errejón : “Le plus grand perdant des élections italiennes c’est Bruxelles” », Mediapart, March 12, 2018.

[58] Luca Comodo, Mattia Forni, “Gli elettori del Movimento: atteggiamenti e opinioni”, in Piergiorgio Corbetta (ed.), M5S. Come cambia il partito di Grillo, Bologna, il Mulino, 2017

[59] Ezio Mauro, “La destra realizzata,” la Repubblica, June 3, 2018; Marco Travaglio, “Senza parole,” il Fatto Quotidiano, June 5, 2018; Claudio Tito, “La alleanza giallo-verde e la nuova destra al potere,” la Repubblica, May 31, 2018.

[60] Ufficio centrale di statistica, “Dati statistici sull’immigrazione in Italia dal 2008 al 2013 e aggiornamento al 2014,” Ministero dell’Interno, Dipartimento per le politiche del personale dell’amministrazione civile e per le politiche del personale, 2014 (http://ucs.interno.gov.it/files/allegatipag/1263/immigrazione_in_italia.pdf).

[61] Eric Fassin, , Populisme, le grand ressentiment, Paris, Textuel, 2017,

[62] Manuel Castells, Communication et pouvoir, Paris, Editions des Sciences de l’Homme, 2013 (ebook 2017).

[63] Gianluca Passarelli, Filippo Tronconi, Dario Tuorto, “Chi dice organizzazione, dice oligarchia”, in Piergiorgio Corbetta (ed.), M5S. Come cambia il partito di Grillo.

[64] Wendy Brown, Wendy Brown, Défaire le Démos. Le néolibéralisme, une révolution furtive, Paris, Amsterdam, 2018 ; Owen Jones, The Demonization of the Working Classe, Londres, Verso, 2011.

[65] Beppe Grillo, “Tagli, ritagli e frattaglie,” beppegrillo.it, May 1, 2012.

[66] Ezio Mauro, “L’anno zero della politica,” la Repubblica, May 10, 2018.

[67] Furio Jesi, Cultura di destra, Milan, Figure nottetempo, 2011 (1979) (ebook).

[68] Luigi Salvatorelli, “La vittoria del Quinto Stato”, La Stampa, 1er November 1922; in Id., Nazionalfascismo, Turin, Einaudi, 1977 [1923].

[69] Interview with Beppe Grillo by Iann Bremmer, US GZeroWorld, July 27, 2018 (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PLLGpCqsyKg); Annalisa Cuzzocrea, “M5S, Grillo avverte Di Maio “Guai a diventare un partito,” la Repubblica, March 3, 2018.

[70] Umberto Eco,”Ur-Fascism. Freedom and Liberation are an unending task”, New York Review of Books, June 22, 1995.

[71] Maurie Agulhon, ” Le peuple à l’inconditionnel “, Vingtième siècle. Revue d’histoire, N°56, 1997, p. 225.

[72] Federico Finchelstein, “Returning Populism to History,” Constellations, No. 4, 2014.

[73] Simonetta Fiori, “Bocciatura degli storici: Iniziativa inopportuna fanno solo marketing,” la Repubblica, June 12, 2016. All quotes, unless otherwise noted, have been translated by me.

[74] Ernesto Galli della Loggia, “I violenti e le parole ambigue,” Corriere della Sera, February 24, 2018.

[75] Alessandro Portelli, “Aperta la diga dell’antifascismo, dilaga l’odio razziale,” Il Manifesto, February 6, 2018.

[76] Pier Paolo Pasolini, Scritti corsari, Milan, Garzanti, 1975, p. 87.

[77] A. Gramsci, Quaderni del carcere, edizione critica dell’Istituto Gramsci a cura di V. Gerratana, Torino, Einaudi, 1975, pp. 2108-2109.

[78] Alberto Toscano, “Notes on Late Fascism,” Historical Materialism, April 2, 2017; Jairus Banaji, “Trajectories of Fascism: Extreme-Right Movements in India and Elsewhere,” The Fifth Walter Sisulu Memorial Lecture, Jamia Millia Islamia, New Delhi, March 18, 2013; David Riesman, The Lonely Crowd : a study of the changing of American Character, New York, Garden city, 1953 (French translation: La foule solitaire, anatomie de la société moderne, Paris, Arthaud, 1965); Dany-Robert Dufour, “Vivre en troupeau en se pensant libre”, Le Monde diplomatique, January 2008.

The murder of Mahsa Amini, a young Iranian Kurdish woman, by the Tehran morality police has sparked large protests in various cities inside Iran. The 22 year old Amini was arrested on September 13 because of her “improper” hijab and died shortly thereafter when she went into a coma following violent beatings by the police.

The murder of Mahsa Amini, a young Iranian Kurdish woman, by the Tehran morality police has sparked large protests in various cities inside Iran. The 22 year old Amini was arrested on September 13 because of her “improper” hijab and died shortly thereafter when she went into a coma following violent beatings by the police.

By Ilya Budraitskis, Oksana Dutchak, Harald Etzbach, Bernd Gehrke, Eva Gelinsky, Renate Hürtgen, Zbigniew Marcin Kowalewski, Natalia Lomonosova, Hanna Perekhoda, Denys Pilash, Zakhar Popovych, Philipp Schmid, Christoph Wälz, Przemyslaw Wielgosz and Christian Zeller

By Ilya Budraitskis, Oksana Dutchak, Harald Etzbach, Bernd Gehrke, Eva Gelinsky, Renate Hürtgen, Zbigniew Marcin Kowalewski, Natalia Lomonosova, Hanna Perekhoda, Denys Pilash, Zakhar Popovych, Philipp Schmid, Christoph Wälz, Przemyslaw Wielgosz and Christian Zeller

Interview with Nataliya Levytska, Deputy Chairperson of the NGPU (Independent Mineworkers Union of Ukraine), by Christopher Ford, Ukraine Solidarity Campaign.

Interview with Nataliya Levytska, Deputy Chairperson of the NGPU (Independent Mineworkers Union of Ukraine), by Christopher Ford, Ukraine Solidarity Campaign.

The uneasiness and disorientation that can seize the observer in the face of the various crises (economic, political, cultural, social and moral) that Italian society has been going through for the last thirty years are multiplied tenfold by the feeling that the horizon is moving away, while there no longer seems to be any shore to cling to. The image of a ship adrift, or of a boat without a paddle, is one of the most telling in a period where there no longer seems to be any vision of the future. We are on the eve of the Italian election–and the black tide of fascism is still rising.

The uneasiness and disorientation that can seize the observer in the face of the various crises (economic, political, cultural, social and moral) that Italian society has been going through for the last thirty years are multiplied tenfold by the feeling that the horizon is moving away, while there no longer seems to be any shore to cling to. The image of a ship adrift, or of a boat without a paddle, is one of the most telling in a period where there no longer seems to be any vision of the future. We are on the eve of the Italian election–and the black tide of fascism is still rising.

Not since the end of the last world war has the threat of a reinvigorated, aggressive and almost universally rising far right been felt as much as today. Why is this so? Because, contrary to what happened during the last six or seven decades, this threat no longer comes from a few small groups or even small parties of nostalgic people from the interwar period, but from a new, unabashed right-wing that governs or is about to govern even countries that are catalogued among the greatest powers in the world!

Not since the end of the last world war has the threat of a reinvigorated, aggressive and almost universally rising far right been felt as much as today. Why is this so? Because, contrary to what happened during the last six or seven decades, this threat no longer comes from a few small groups or even small parties of nostalgic people from the interwar period, but from a new, unabashed right-wing that governs or is about to govern even countries that are catalogued among the greatest powers in the world!

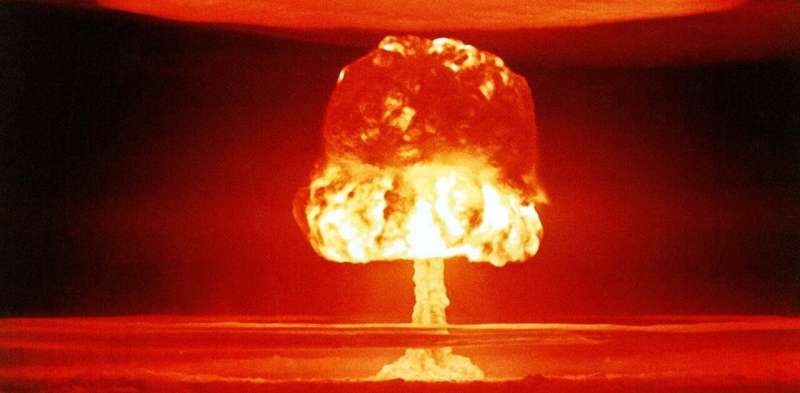

Given the danger of nuclear conflagration, should the peace movement demand – as some have suggested — that the United States and NATO stop providing arms to Ukraine as a way to avoid provoking Russia?

Given the danger of nuclear conflagration, should the peace movement demand – as some have suggested — that the United States and NATO stop providing arms to Ukraine as a way to avoid provoking Russia?

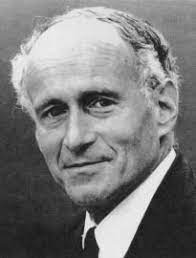

It was in 1944-45, as Paris was liberated, that Schwartz made his discovery of what in mathematics are called “distributions” or sometimes “generalized functions,” his great contribution to mathematical theory. Though, when in 1950 the International Mathematical Union awarded him the Fields Medal (comparable to the Nobel Prize), the United States refused to admit him to the country for the ceremony. In any case, with the war over, he now pursued his academic career in earnest. He became a professor at Nancy University, then moved to the Sorbonne in 1952, and in 1958 he became a professor as well at the École Polytechnique (EP). He taught there until 1980.

It was in 1944-45, as Paris was liberated, that Schwartz made his discovery of what in mathematics are called “distributions” or sometimes “generalized functions,” his great contribution to mathematical theory. Though, when in 1950 the International Mathematical Union awarded him the Fields Medal (comparable to the Nobel Prize), the United States refused to admit him to the country for the ceremony. In any case, with the war over, he now pursued his academic career in earnest. He became a professor at Nancy University, then moved to the Sorbonne in 1952, and in 1958 he became a professor as well at the École Polytechnique (EP). He taught there until 1980.

At the end of the nineteenth century, family life, feeding practices, and children’s health transformed in the industrializing world as economic and scientific innovation coalesced around the newly emerging needs of capital.

At the end of the nineteenth century, family life, feeding practices, and children’s health transformed in the industrializing world as economic and scientific innovation coalesced around the newly emerging needs of capital.

“This is madness,”

“This is madness,”

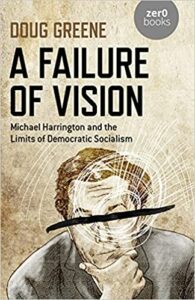

Doug Greene, A Failure of Vision: Michael Harrington and the Limits of Democratic Socialism. Washington: 2021. 260 pages. Notes. Bibliography. No index.

Doug Greene, A Failure of Vision: Michael Harrington and the Limits of Democratic Socialism. Washington: 2021. 260 pages. Notes. Bibliography. No index.