Famous documentary film-maker Ken Burns’s newest production is The U.S. and the Holocaust. It’s quite critical of U.S. conduct during that time and exposes antisemitism in the U.S. during that era. But it falls down in one area on the failure of the Allies to bomb Auschwitz. It wrings its hands and goes back and forth a little, but the final word is given to a historian who says, “I don’t think there’s a right answer in whether we should have bombed Auschwitz … because I don’t think there’s a way to look back and say we did the right thing. It’s one of those tragic questions.”

Back in 1978 David Wyman wrote a book The Abandonment of the Jews: America and the Holocaust. In it he charged that American and British political leaders during the Holocaust, including President Roosevelt, turned down proposals that could have saved hundreds of thousands of European Jews from death in German concentration camps. Ever since there have been periods of furious historical debate on the subject. It’s time to renew that debate.

Let’s go deep into the background. Auschwitz was completed in 1940. Activities there were a closely guarded secret. Yet in a series of reports the Polish government-in-exile talked about its horrors in that same year. By 1942 news of the mass slaughter of Jews had directly reached the Allies. For instance the British Daily Telegraph on June 25 printed an article “Germans Murder 700,000 Jews in Poland.” The sub-headline was “Travelling Gas Chambers”. It was based on reports sent to Polish Bund leader Szmul Zygielbojm. In August of 1942 World Jewish Congress representative Gerhart M. Riegner sent reliable information that he had received from a high-placed source revealing Hitler’s plans to annihilate millions of European Jews, to the British Foreign Office who sent it on to the U.S. State Department.

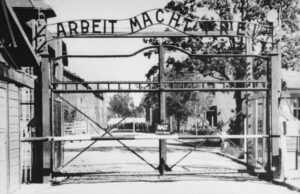

The Germans had set up a series of concentration camps and other kinds of camps that the U.S. Holocaust Museum calls “killing centers.” Auschwitz was one of them. Historian Rafael Medoff writes, “At a March 24, 1944, press conference, FDR, after first discussing Philippine independence, farm machinery shipments, and war crimes in Asia, acknowledged that Hungary’s Jews are now ‘threatened with annihilation’ because the Germans were planning ‘the deportation of Jews to their death in Poland.’”

If there was any doubt about what was going on inside Auschwitz, that was erased when two Jewish prisoners, Rudolf Vrba and Alfred Wetzler, escaped in April 1944 and told their stories. They had been Sondercommando, Jewish slaves of the Nazis in the camp. They made it across Poland to Slovakia and testified to a Jewish Council there. In a 33-page report originally written in Slovak they told of the layout of the camp, the tattoos, the “selection process,” and the methods of mass extermination. The report, sometimes called the “Auschwitz Protocols,” was translated into German and Hungarian by the end of the month.

One of the first people to read the report was Rabbi Dov Weissmandl of Slovakia. He had seen deportations and now he knew what was happening to the deportees. He sent the Protocols to many world leaders along with a passionate letter demanding action, explaining that 10,000 Jews a day were being killed in the camp. He called for the bombing of Auschwitz, full well knowing it was filled with Jewish prisoners. A copy of the Protocols reached Roswell McClelland, agent of the U.S. War Refugee Board. That body had been created by Roosevelt to see what could be done to rescue Jews. McClelland was in Switzerland, but he sent a cable outlining the report to Washington, including the pleas that the rail lines and crematoria be bombed. He wrote that already 1.5 million had been murdered and that plans were underway to exterminate the Hungarian Jews.

On May 15, 1944, the deportations of the Hungarian Jews began. They went on at a furious rate for two months. Ultimately 437,000 Hungarian Jews were murdered in Auschwitz.

On June 24, John Pehle, the head of the War Refugee Board, passed along the recommendation to bomb to John McCloy, Assistant Secretary of War. About a week later McCloy wrote back that the request was “impracticable.” He said it could only happen if there was “diversion of considerable air support.”

In London the request to bomb Auschwitz reached the desk of Anthony Eden, the British Foreign Secretary and a close confidant of Winston Churchill. In a BBC-produced film “1944: Should We Bomb Auschwitz?” Jewish Agency representatives are depicted meeting with Eden on July 6. He told them that Churchill was in favor of an attack on Auschwitz. In a memo to Eden, Churchill had written that the German mass murders were “the greatest and most horrible crime ever committed in the whole history of the world” and wrote “get anything out of the air force you can and invoke me if necessary”.

The head of the Air Ministry, Archibald Sinclair, and Eden agreed the Americans were better able to study the feasibility of the bombing and so the idea was sent to General Carl Spaatz, Commander of Strategic Air Forces in Europe. He said “Yes, it sounds like something I’d be willing to do.”

That was a close as any of the Allies ever came to targeting the Auschwitz-Birkenau death camp.

Before bombing an area, spy planes would fly over it and take pictures. In 1944 spy planes had flown over the area in occupied Poland that included Auschwitz. They were looking for factories to bomb. Bombers were routinely attacking targets deep in Eastern Europe “right in the vicinity of Auschwitz.” But apparently, while thousands were being slaughtered each day in the camp, there was never any specific missions to photograph the camp and approaching rail lines.

Churchill’s enthusiasm to destroy the camp cooled. On September 1, Churchill informed Chaim Weizmann of the Jewish Agency that technical difficulties prevented the bombing.

Yet on Sept. 13 the allies did bomb Auschwitz-Birkenau! They hit it with 2000 bombs…by accident. The target was a nearby I.G. Farben factory. There’s no report that this raid was extraordinary or that an exceptional number of planes had been shot down. It was just another bombing run. That should totally refute the argument that there were “technical” problems standing in the way of attacking the camp.

On November 18 Assistant Secretary of War McCloy wrote to the War Refugee Board again telling it that the bombing of Auschwitz was beyond the capacity of the U.S. government since it would require 2,000 miles of travel from British bases. His arguments were completely punctured in a Washington Post article by Mortin Mintz in 1983. Mintz noted that “in all, the 15th’s B17s and B24s flew more than 2,280 sorties to attack targets close to Birkenau.”

The U.S. in 1944 had bases in Foggia, in southern Italy, from which it was bombing Poland. Early in May, according to historian David S. Wyman, “Lt. Gen. Ira C. Eaker, chief of Allied air forces in Italy, assured Air Force leaders that his heavy bombers could make daylight raids on Blechhammer, an oil plant 47 miles from Auschwitz, and that others at Auschwitz and Odertal ‘might also be attacked simultaneously’.”

The claim by the historian in Burns film that Nazis could rebuild railroad tracks is true. But that didn’t prevent tracks from being bombed again and again during the war to stop troop transport and replacing bombed crematoriums would be considerably more difficult.

What about the argument that it would have been wrong for Allied bombs to kill innocent Jews in the camps. It’s easy for us sitting comfortably today to simply say it would have been “worth it.” But consider the opinion of Auschwitz prisoners who survived. One was Elie Wiesel who witnessed an August 20 bombing attack on the Farben factory that was 5 miles away. In a 2019 article Rafael Medoff wrote that “Elie Wiesel, then age 16, was a slave laborer in that section of the huge Auschwitz complex…. Many years later, in his best-selling book Night, Wiesel wrote: ‘If a bomb had fallen on the blocks [the prisoners’ barracks], it alone would have claimed hundreds of victims on the spot. But we were no longer afraid of death; at any rate, not of that death. Every bomb that exploded filled us with joy and gave us new confidence in life. The raid lasted over an hour. If it could only have lasted ten times ten hours!’” Another voice is that of David Blitzer, the father of CNN’s Wolf Blitzer. David Blitzer actually grew up in Oświęcim (Auschwitz is a Germanized name for the city). In an interview in the 1980’s he said inmates of the camp were “praying” for the camp to be bombed.

With Soviet troops approaching in the fall of 1944, Himmler ordered destruction of parts of Auschwitz at the end of November. Other killing camps had been dismantled and buildings buried in efforts to cover up Nazi crimes. Yet Crematorium V at Auschwitz was still operating until the day the Soviets liberated the camp in January 1945.

It should be noted that one crematorium was deliberately attacked, but not by the Allies. That honor belongs to Sonderkommando, the slaves of the camp. Crematorium IV was partially burned during the Sonderkommando mutiny on October 7, 1944.

In total frustration, War Refugee Board head John Pehle leaked copies of the Auschwitz Protocols to the press. It was a sensation and was widely covered. On December 3, the article came out in the Washington Post and the word “genocide” was used in the major media for the first time.

What about the Soviet Union and Auschwitz? With all the debate about whether the “Allies” should have bombed Auschwitz there’s almost nothing written about the responsibility of that powerful member of the Allies.

In 1944, Soviet forces were closer to Auschwitz than were the British or U.S. Kyiv, Ukraine, was liberated by the Soviets in November 1943. It was 578 miles from Auschwitz. Ternopil, Ukraine was liberated around May 1, 1944, and was 329 miles to Auschwitz. In July 1944 the Red Army entered the Majdanek death camp. It was less than 250 miles from Auschwitz. So Auschwitz was in range of Soviet bombers. And remember Jews weren’t the only people killed at Auschwitz. 15,000 Soviet troops were murdered there, too.

In the BBC film, historian William D. Rubinstein dismisses the whole idea saying Stalin was as likely to bomb the camps as he was to stand on his head in Red Square in the middle of winter. But why take that conclusion as a given? Was the question ever raised to the Soviets by Churchill or Roosevelt? Why wouldn’t the Soviets have listened to a U.S.-British request? In those days we were allies and the U.S. was sending weapons to the Soviet Union through Lend Lease. That program didn’t end until September of 1945. Certainly, Churchill or Roosevelt could have made the effort.

One argument that always comes up is that the Allies’ first responsibility was to win the war and that any humanitarian act could be considered a “diversion.” But did the Allies only use their forces for direct military efforts? No, they diverted a lot of their forces. Consider the “strategic bombing” campaigns. When planes were first used in war it was to attack enemy troops as a sort of super mobile artillery. But soon a new idea was born, to use planes to bomb industry and to bomb civilians “to break their will.” The notion was incorporated into the phrase “strategic bombing,” invented by Giulio Douhet, an Italian military theorist. He was later chief of aviation for Mussolini. Strategic bombing was tried out in 1937 in Guernica in the Basque country of Spain to gruesome effect and causing considerable outrage around the world.

Yet as the war ground on the Allies embraced the tactic. They bombed factory and transportation centers and then targeted the largest German cities. Writing on the site of the U.S. Naval Institute retired Colonel Everest E. Riccioni, U.S. Air Force stated, “Air Marshal [Baronet Arthur] Harris ordered a campaign of terror, inflicting pain by large-scale, indiscriminate destruction of Germany’s industrial cities, euphemistically called ‘de-housing.’ He intended to crack the German population’s will to resist.”

A euphemism frequently mentioned was the need to break “morale.” To break morale they used firebombs to obliterate Darmstadt, Würtzburg, and Dresden. To drop these bombs, they diverted planes that might have bombed Nazi troop positions.

Yet with all that the war in Europe went on and on until Russian troops pummeled Hitler’s bunker. So it can’t be claimed that of the 3.4 million tons of bombs dropped during the war none could have been diverted to destroy the death machines of Auschwitz or the railroad tracks leading to the camp or the locomotives that pulled the trains.

Bombing Auschwitz would not have been “impracticable” and it would not have diverted significantly from the actual war effort. It would have saved thousands or tens of thousands of lives and would have let the world know that Allied moral outrage was more than feel-good propaganda.

Excellent article. Are you also saying that the Soviet Union could have or should have bombed Auschwitz? Have any historians weighed in on that question?

Thansk.

To answer the question by another reader I think “yes”, the Soviet Union should have bombed Auschwitz. They certainly were close enough. Someday Russian historians should look at the WW2 Soviet archives and find out whether Stalin, FDR and Churchill or their top officials ever discussed the question.

Arnold Schwarzenegger visited the Auschwitz Museum complex at the end of September 2022

Speaking alongside Auschwitz Jewish Center Foundation Chairman Simon Bergson, the son of Auschwitz survivors, Schwarzenegger said: “He was born after the Second World War to this wonderful Jewish family, and I was the son of a man who fought in the Nazi war and was a soldier. One generation later, here we are. … We both fight prejudice and hatred and discrimination.”

Right after the Jan. 6 U.S. attempted insurrection Schwarzenegger made a powerful video denouncing the riot, admitting that his father had been a Nazi member and denouncing lies that ruined a generation.

He compared the January 6 riot to Kristallnacht.

“It was a night of rampage against the Jews carried out in 1938 by the Nazi equivalent of the Proud Boys. Wednesday was the Day of Broken Glass right here in the United States. The broken glass was in the windows of the United States Capitol.”