The Feminist Initiative Group

The Feminist Initiative Group

Sign the manifesto

We, feminists from Ukraine, call on feminists around the world to stand in solidarity with the resistance movement of the Ukrainian people against the predatory, imperialist war unleashed by the Russian Federation. War narratives often portray women* as victims. However, in reality, women* also play a key role in resistance movements, both at the frontline and on the home front: from Algeria to Vietnam, from Syria to Palestine, from Kurdistan to Ukraine.

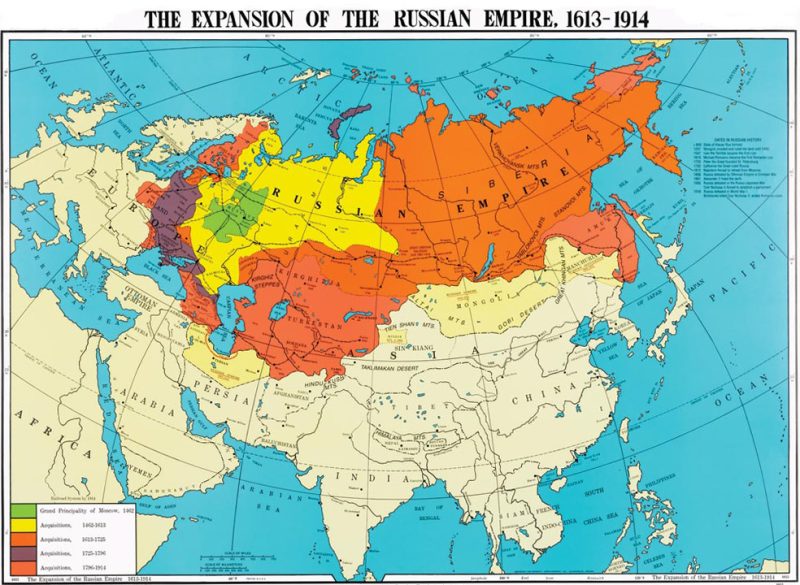

The authors of the Feminist Resistance Against War manifesto deny Ukrainian women* this right to resistance, which constitutes a basic act of self-defense of the oppressed. In contrast, we view feminist solidarity as a political practice which must listen to the voices of those directly affected by imperialist aggression. Feminist solidarity must defend women’s* right to independently determine their needs, political goals, and strategies for achieving them. Ukrainian feminists were struggling against systemic discrimination, patriarchy, racism, and capitalist exploitation long before the present moment. We conducted and will continue to conduct this struggle both during war and in peacetime. However, the Russian invasion is forcing us to focus on the general defense effort of Ukrainian society: the fight for survival, for basic rights and freedoms, for political self-determination. We call for an informed assessment of a specific situation instead of abstract geopolitical analysis which ignores the historical, social and political context. Abstract pacifism which condemns all sides taking part in the war leads to irresponsible solutions in practice. We insist on the essential difference between violence as a means of oppression and as a legitimate means of self-defense.

The Russian aggression undermines the achievements of Ukrainian feminists in the struggle against political and social oppression. In the occupied territories, the Russian army uses mass rape and other forms of gender-based violence as a military strategy. The establishment of the Russian regime in these territories poses the threat of criminalizing LGBTIQ+ people and decriminalizing domestic violence. Throughout Ukraine, the problem of domestic violence is becoming more acute. Vast destruction of civilian infrastructure, threats to the environmental, inflation, shortages, and population displacement endanger social reproduction. The war intensifies gendered division of labor, further shifting the work of social reproduction – in especially difficult and precarious conditions – onto women. Rising unemployment and the neoliberal government’s attack on labor rights continue to exacerbate social problems. Fleeing from the war, many women* are forced to leave the country, and find themselves in a vulnerable position due to barriers to housing, social infrastructure, stable income, and medical services (including contraception and abortion). They are also at risk of getting trapped into sex trafficking.

We call on feminists from around the world to support our struggle. We demand:

– the right to self-determination, protection of life and fundamental freedoms, and the right to self-defense (including armed) for the Ukrainian people – as well as for other peoples facing imperialist aggression;

– a just peace, based on the self-determination of the Ukrainian people, both in the territories controlled by Ukraine and its temporarily occupied territories, in which the interests of workers, women, LGBTIQ+ people, ethnic minorities and other oppressed and discriminated groups will be taken into account;

– international justice for war crimes and crimes against humanity during the imperialist wars of the Russian Federation and other countries;

– effective security guarantees for Ukraine and effective mechanisms to prevent further wars, aggression, escalation of conflicts in the region and in the world;

– freedom of movement, protection and social security for all refugees and internally displaced persons irrespective of origin;

– protection and expansion of labor rights, opposition to exploitation and super exploitation, and democratization of industrial relations;

– prioritization of the sphere of social reproduction (kindergartens, schools, medical institutions, social support, etc.) in the reconstruction of Ukraine after the war;

– cancellation of Ukraine’s foreign debt (and that of other countries of the global periphery) for post-war reconstruction and prevention of further austerity policies;

– protection against gender-based violence and guaranteed effective implementation of the Istanbul Convention;

– respect for the rights and empowerment of LGBTIQ+ people, national minorities, people with disabilities and other discriminated groups;

– implementation of the reproductive rights of girls and women, including the universal rights to sex education, medical services, medicine, contraception, and abortion;

– guaranteed visibility for and recognition of women’s active role in the anti-imperialist struggle;

– inclusion of women in all social processes and decision-making, both during war and in peacetime, on equal terms with men;

Today, Russian imperialism threatens the existence of Ukrainian society and affects the entire world. Our common fight against it requires shared principles and global support. We call for feminist solidarity and action to protect human lives as well as rights, social justice, freedom, and security.

We stand for the right to resist.

If Ukrainian society lays down its arms, there will be no Ukrainian society.

If Russia lays down its arms, the war will end.

Sign the manifesto

July 7, 2022

As of 08.07.2022, 346 people and 31 organizations signed the manifesto.

Individual signatures

Victoria Pigul, Feminist, activist of “Social Movement”

Oksana Dutchak, Feminist, co-editor of Commons: Journal of Social Criticism

Oksana Potapova, Feminist activist, researcher)

Anna Khvyl, Feminist, composer, curator

Daria Saburova, Researcher, member of the “European Network of Solidarity with Ukraine”

Hanna Manoilenko, Activist at FemSolution collective

Hanna Perekhoda, Member of the “European Network of Solidarity with Ukraine”, “Comité Ukraine Vaud” and “solidaritéS Vaud”

Iryna Yuzyk, Human rights activist, journalist

Ana More, Journalist at “Hromadske radio”, activist human rights activist

Valerija Zubatenko, Human rights activist

Marta Guda, IT worker

Victoria Vidiborets, Feminist blogger and activist

Olga Kostina, Member of the initiative group “Equals in Kryvyi Rih” promoting and supporting gender equality in the city of Kryvyi Rih

Natalia L., Co-author of a fanzine about women and trans people in precarious work settings

Marta Chumalo, Feminist

Veronika Kanigina, Student, feminist

Kateryna Mischenko, Publisher

Anastasia Sereda, Teacher, intersectional feminist

Oleksandra Manko, Feminist activist

Oleksandra Lysogor, Feminist activist

Olga Martynyuk, Senior lecturer at the History Department of the National Technical University of Ukraine “Igor Sikorsky Kyiv Polytechnic Institute”

Alona Lyasheva, Member of the editorial board of Commons: Journal of Social Criticism

Anastasia Grychkowska, Activist, student

Lilya Badekha, Independent feminist

Kateryna Semchuk, Queer feminist, journalist, co-editor of Politychna Krytyka

Nargiza Shkrobotko, Member of the Association of Femencamp graduates

Yaryna Degtyar, Member of “Feminist Workshop”

Ksenia Shaloimenko, Journalist

Mariyana Teklyuk, Member the feminist group “Resistanta”

Anastasia Chebotaryova, Member of the “Feminist Lodge”, a grassroots initiative of young feminists

Yustyna Kravchuk, Author, translator, Visual Culture Research Center/Kyiv Biennale

Daria Gorobets, Member of “Yafa”, a feminist group from Zaporijjia

Maryna Usmanova, Head of the feminist organization “Insha”

Maria Kanigina, Student

Oksana Kis, Researcher, member of the Ukrainian Association of Women’s History Researchers

Julia Vlaskina, Musician

Tamara Martseniuk, Assistant professor at the Sociology Department of the National University “Kyiv-Mohyla Academy”

Hanna Tsyba, Cultural studies scholar, curator of cultural projects, journalist

Liza Kuzmenko, Head of the NGO “Women in Media”

Karyna Lazaruk, Media researcher, infographer

Anastasia Fischenko, Student at the Taras Shevchenko National University of Kyiv, member of the vegan and anarchist organization “Solidarity Kitchen”

Tamara Khurtsidze, Student, volunteer

Nadia Parfan, Film director, producer, curator of cultural projects

Tamara Zlobina, Editor-in-chief of the online media resource “Gender in detail”

Golovan Marya, Activist of the initiative group “Equals in Kryvyi Rih”, supporting women and defending their rights

Julia Lutiy-Moroz, Member of the “FemSolution” collective

Oleksandra Yakovleva, Medical worker, feminist, LGBT+ activist, volunteer at a horizontal organization specialised in humanitarian aid and provision of military personnel with necessary protective equipment and medicine

Daria Neopochatova, Psychologist

Oksana Slobodyana, Nurse, medical workers’ labor rights activist, co-founder of the nurses’ union “Be like Nina

Olena Tarasik, Member of the initiative group “Equals in Kryvyi Rih”

Svitlana Babenko, Scholar and educational worker, head of the Gender Studies program at the Taras Shevchenko National University

Oksana Briukhovetska, Artist, art curator

Hanna Dovgopol, Coordinator of the “Gender Democracy” program at the Heinrich Böll Foundation, Kyiv-Ukraine Office

Oksana Pavlenko, Editor-in-chief of the divoche.media

Oksana Popadyuchenko, Business analyst at Ukrnafta

Iryna Dobrovynska, Freelancer

Zach Orliva, Psychologist

Maryna G., Autonomous activist

Anastasia Shevelyova, Designer

Victoria Narizhna, Translator, cultural manager

Maya Bicek, Designer at grouping salt

Ganna Kasyanova, Artist

Ninel Strelkovska, Learning experience designer

Kateryna Pankiv, Psychologist

Natalka Cheh, Grassroots activist

Olena Dyachenko, Illustrator

Katya Chizayeva, Dancer

Anna Pochtarenko, Feminist

Maryna Shevtsova, PhD, postdoctoral researcher

Yulia Yurchenko, Political economist at Political Economy, Governance, Finance and Accountability Institute, University of Greenwich, UK

Christine Sobko, ECOM

Svitlana Dubina, Human rights activist

Yana Dziґa, Grassroots activist, social communicator

Svitlana Libet, Author and editor

Anna Litvinova, Feminist, LGBT and lesbian activist

Olga Papash, Culture researcher, community activist

Kateryna Tarasyuk, Lecturer in Slavic languages and cultures at the University of Strasbourg

Olya Fedorova, Artist

Kateryna Turenko, Activist in the feminist initiative “FemSolution”, editor, artist

Anastasia Ryabchuk, Associate Professor, Department of Sociology, NaUKMA, member of the editorial board of Commons: Journal of Social Criticism

Tonya Melnik, Artist, queer feminist activist, member of the ReSew clothing cooperative

Olga Vesnianka, Co-founder of the campaign against sexism Povaha, women rights defender

Vita Bazan, Kinesthetics

Nastya Melnichenko, Community activist

Victoria Demidova, International organization

Julia Knyupa, Visual facilitator

Kateryna Tyaglo, Writer, copywriter, social scientist

Kateryna Kostrova, Feminist, social activist

Julia Knyaziuk, Association “Positive Women” in Ivano-Frankivsk, protection of women’s rights

Lillia Grinyuk, Association “Positive Women”

Julia Dupeshko-Jus, Community activist, feminist, member of “Steps to the Future” and “One of Us” initiative

Diana Asadcheva, Activist of the LBTQI+ organization “Insight”

Natalia Omelchuk, activist, co-organizer of the “One of Us” initiative

Natalia Titiyova, NGO “ Ukraine – Time to unite”

Olena Gulenok, Sociologist, researcher

Viktoria K., FemSolution

Marta Havryshko, Researcher of sexual violence in war

Olha Zaiarna, Peacebuilding, women’s cooperation for human security

Yulia Liutyi-Moroz, Activist of FemSolution

Nataliya Vyshnevetska, NGO “D.O.M.48.24” (women’s rights, IDPs)

Olha Kukula, Project manager, NGO “D.O.M.48.24”, trainer on sexual education, tutoress in “Nevhamovni”

Tetiana Slobodian, Activist

Yulia Kulish, PhD student of the Department of Literature Studies, NaUKMA

Valeria Lazarenko, Feminist, academic researcher

Dmytro Kruhlov, IT

Svitlana Drozd, Actress, programming teacher

Ruslana Koziienko, Anthropologist

Daria Yemtsova, Historian in the Memorials Brandenburg an der Havel

Yuliia Kishchuk, Researcher

Hanna Syniavska, Front-end developer

Anna Nikitina, Feminist

Lilia Hryhorieva, Member of the Union of communication workers of Ukraine

Alina Bilokonenko, Editor at a publishing house

Khrystyna Liakh, Feminist, journalist, volunteer in charity foundation “Patronus”

Oleksandra Zimko, Editor, translator, feminist and LGBTQ+ activist

Anastasia Semilutska, Teacher

Anastasia Rudnitska, Dance trainer

Ania Kudrinova, Teacher, student

Masha Lukianova, artist, activist, member of the sewing cooperatives ReSew and Shvemy

Daria, IT

Oleksandr Kravchuk, economist, co-editor of Commons: Journal of Social Criticism

Olha Larina, Artist, designer

Diana Melnykova, Linguist

Olena Martynchuk, Anthropologist, curator

Anna Kovalchuk, Feminist

Roksolana Vynnyk, NGO “D.O.M.48.24”

Artur Sumarokov, Playwright and cinema critic

Maria Holovan, activist of the initiative group “Equals in Kryvyi Rih”

Yulia Kharchenko, Dance teacher

Ekaterina Lisovenko, Artist

Denys Nikula, Programmer

Iryna Shevchuk, Housewife

Tetiana Reznikova, Psychologist

Larysa Opria, Feminist

Kateryna Khanieva, Feminist

Kateryna Polevianenko, Product designer

Tetiana Shymanchuk, Student, feminist

Daria Siomina, Feminist activist

Svitlana Vozniak, Housewife

Maryna Rudnytska, Lawyer

Liudmyla Tiurnikova, Entrepreneur

Maria Bakalo, Teacher of modern dance

Victoria Amelina, Writer, founder of the New York Literature Festival, member of PEN Ukraine

Olena Zaitseva, Lawyer

Taisia Fedorova, Editor

Organizations

Feministychna Maisternia /Feminist Workshop, Feminist organization

Rebel Queers, Feminist organization

Feministychna Loga/Feminist lodge, Grassroots feminist organization currently providing vulnerable women and their families with humanitarian aid

Sfera/Sphere, Organization representing the LGBT+ community and the women of Eastern Ukraine

Insha/Different, LGBTQI+ feminist and inclusive organization from city of Kherson

FemSolution, Grassroots feminist initiative

Insait/Insight, LGBTQI+ organization

Center for Social and Gender Studies ”New Life”, Human rights organization specialized in gender mainstreaming and struggle against gender based violence

Development of Democracy Center, Human rights organization

Khlib Nasushnyi/Daily Bread, Horizontal freeganic cooperative, engaging in food activism

QueerLab, Cooperative that provides workplaces and/or necessary services and products to refugees

Institute of Gender Programs, Organization promoting human rights and gender equality in the defense sector in the context of Russian aggression

D.O.M.48.24, women’s rights, development of social entrepreneurship, development of culture

Sotsialnyi Rukh/Social movement, Left organization that stands on the principles of people’s power, anticapitalism, antixenophobia

Politychna Diya Zhinok/Political action of women, Defending women’s political rights

Ekolohichna Platforma/Ecological platform, Eco-anarchists

International support

Individual signatures

Elisa Moros, Feminist and anticapitalist activist, NPA, ENSU Feminist Collective (France)

Alessandra Mezzadri, Feminist Political Economist, SOAS (UK)

Stefanie Prezioso, MP-Ensemble à Gauche, Professor of History University of Lausanne (Switzerland)

Catherine Samary, Economist and political scientist (France)

Ludivine Bantigny, Historian (France)

Zofia Malisz, Razem (Poland)

Kavita Krishnan, Marxist feminist activist (India)

Riki Van Boeschoten, Professor of Anthropology, University of Thessaly (Greece)

Geneviève de Rham, Feminist, trade union activist (Switzerland)

Christine Poupin, Spokesperson NPA (France)

Paula Kaufmann, Coletivo Juntas! (Brazil)

Sherry Baron, Public Health Physician and Professor, City University of New York (USA)

Dawn Marie Paley, Journalist (Mexico/Canada)

Elea Foster, Copy editor (Greece)

Joel Beinin, Donald J. McLachlan Professor of History, Emeritus, Stanford University (USA)

Sonia Mitralia, Feminist Asylum, ENSUFEMINIST (Greece)

Vivi Reis, Federal Deputy, PSOL (Brazil)

Nancy Holmstrom, Professor Emerita in Philosophy, Rutgers University, New Politics journal (USA)

Fernanda Melchionna, Federal Deputy, PSOL (Brazil)

Céline Cantat, Sociologist (France)

Nadia Oleszczuk, KP Youth OPZZ / labor union (Poland)

Laura Esikoff, Psychoanalyst (USA)

Sâmia Bomfim, Federal Deputy, PSOL (Brazil)

Luana Alves, Councilor of São Paulo, PSOL (Brazil)

Marie Fonjallaz, Grève féministe Vaud/Feminist strike Vaud (Swirzerland)

Frieda Afary, Iranian American Librarian, author of “Socialist Feminism: A New Approach” (USA)

Ania Deryło, FemFund (Poland)

Janna Araeva, Bishkek Feminists (Kyrgystan)

Athena Moss Sypsa, Artist (Greece)

Penelope Duggan, International Viewpoint (France)

Nurzhan Estebes, Bishkek Feminist Initiative (Kyrgystan)

Yuliya Yurchuk, Historian, Södertörn University (Sweden)

Nino Ugrekhelidze, Feminist activist, Lead on Philanthropic Partnerships at VOICE Amplified (Georgia)

Rohini Hensman, Writer, researcher and activist (India)

Gabriele Dietrich, Pennurimai Iyakkam Women’s Movement, Tamil Nadu (India)

Pamela, Independent journalist (India)

Meera Sanghamitra, National Alliance of People’s Movements committed to a nuclear and war free world (India)

Irina Novac, Feminist activism (Romania)

Shubhra Nagalia, Gender Studies, School of Human Studies, Faculty (India)

Kelly Shawn Joseph, Aid worker, working on women’s rights (USA)

Jacline Choulat, Grève féministe Vaud /Feminist strike Vaud (Switzerland)

Elisabeth Germain, Feminist activist (Canada)

Shabnam Hashmi, Socialist activist/democracy/gender equality/ANHAD (India)

Ranjana Padhi, Feminist activist and author (India)

John Meehan, Activist (Ireland)

Dawid Zygmunt, Razem (Poland)

Dan La Botz, Co-Editor, New Politics (USA)

Sam Farber, Retired Professor (USA)

Thomas Harrison, Retired teacher (USA)

Hewson Susie, Bodywise (UK) Ltd – Natracare, menstrual equity (UK)

Anuradha Banerji, Activist, Saheli Women’s Resource Centre, New Delhi (India)

Ashima Roy Chowdhury, Saheli women’s resource centre, New Delhi (India)

Lewis Emmerton, SheDecides (UK)

Melampianaki Zetta, Editorial team of www. elaliberta.gr (Greece)

Ema Kurtova, Feminist organization “Aspekt” (Slovakia)

Vanessa Monney, Grève féministe Suisse/Femist strike Switzerland collective (Switzerland)

Huayra Llanque, Attac (France)

Carla Bonfichi (Italy)

Catherine Bloch-London, Attac (France)

Jean Batou, Deputy for Ensemble à Gauche, Penser l’Émancipation Network (Switzerland)

Christiane Marty, member of the Copernic Foundation (France)

Ferrua, Julie, National secretary at Union Syndicale Solidaires/Solidaires labor union (France)

Rao Vijay Rukmini, Feminist activist (India)

Lissy Joseph, Telangana Domestic Workers Union (India)

Murielle Guilbert, Union Syndicale Solidaires/Solidaires labor union (France)

Cybèle David, National secretary at Union syndicale Solidaires/Solidaires labor union (France)

Janick Schaufelbuehl, Historian (Switzerland)

Nara Cladera, Fédération SUD éducation/Labor union federation in education SUD (France)

Lucie Hulin, Fédération SUD éducation/Labor union federation in education SUD (France)

Thomas Weyts, SAP – Antikapitalisten (Belgium)

Sasha, Feminist Anti-war resistance (Russia)

Jana Juráňová, Writer, translator (Slovakia)

Marta Puczyńska, Feminist, anti-repression activist (Poland)

Maryna Shevtsova, Visiting professor, University of Ljubljana (Slovenia)

Tereza Hendl, Philosopher, founder of the Central and East-European Feminist Research Network (Czech Republic)

Liliya Vezhevatova, Feminist activist, member of the Feminist Anti-war Resistance (Russia)

Sherin Idais, Student (Palestine)

Elisabetta Michielin, IT/Le Baba Jaga Pordenone (Italy)

Julia Escalante De Haro, RAÍCES Análisis de Género para el Desarrollo/RAÍCES Gender Analysis for Development (Mexico)

Daniel James, Philosopher (Germany)

Mina Baginova, Social anthropologist and activist (Czech Republic)

Anicet Lossa Londjiringa, Association for Preservation and Protection of Lake Ecosystems and Sustainable Agriculture (DR Congo)

Francesca Tosto, Retired (Italy)

Selin Cagatay, Feminist activist, researcher (Austria)

Anna, Public relations manager (Russia)

Maria Doroshka, Student (Belarus)

Valentina, Student at the Rostov State Medical University (Russia)

Evgeniya, Musician, video blogger (Russia)

Ulyana Pranevich, Student (Belarus)

Lena, Russian as a foreign language instructor (Russia)

Anastasia Goltsman, EN-RU game localization (Russia)

Nora González Chacón, Agenda Ciudadana por la Educación y UNED/ Citizen’s Agenda for Education and State Distance University (Costa Rica)

Ekaterina Sokolova, IT, Czech Republic

Maryann Abbs, herbalist (Canada)

Kira Znamenskaya, Pediatrician (Russia)

Anon, Philologist (Russia)

Kropotkina, Writer (Russia)

Victoria, Banker (Russia)

Ekaterina V, VIM specialist, feminist (Montenegro)

Asya Kolsanova, Feminist, (Russia/Germany)

Anastasia Liebenstein, Manager (Russia)

Mikko Lipiäinen, Artist, Fennobahia (Finland)

Eugenia H., Philologist (Russia)

Dee Meijer, Artist (Germany)

Monika Ławnicka, Ukraine’s supporter (Poland)

Anastasia, Financial sector worker (Russia)

Juliette Farjat, Philosophy teacher (France)

Anastasiia Markova, Student (Switzerland)

Alexis Cukier, Philosopher (France)

Yana Borisova, Catering worker (Russia)

Anna Wiatrowska, Queerowyfeminizm/queer feminist education account on Instagram (Poland)

Adele Kaufman, Feminist opposed to the “Russian world” (Russia)

Zuzana Uhde, Social and feminist researcher (Czech Republic)

Magdalena Zolkos, Associate professor in political science (Finland)

Ksenia, Architect (Russia)

Nana Kobidze, Researcher (Georgia)

Iuliia Avramenko, Technical writer, (Georgia)

Alina Nichikova, Feminist Anti-War Resistance (Russia)

Amalia, Radfem (Russia)

Joan McKiernan, Activist (USA)

Maria Rybina, Designer, feminist, Anti-War Resistance (Russia)

Svetlana Peshkova, Activist, mother, and anthropologist (USA)

Miroslava Udina, artist, feminist, volunteer, Feminist Anti-War Resistance (Russia)

Yana, Radical feminist (Russia)

Moira Pezzetta, Young Feminist Europe (Austria)

Meyer Nicolas, Public school teacher (France)

Dick Nichols, European correspondent, Green Left (Australia/ Spain)

Anastasia V., Feminist, artist (Russia)

Victoria Scheyer, Feminist activist (Germany)

Kristin Halverson, Historian, activist (Sweden)

Vitalia Potapova, Student, feminist, activist, political convict (Russia)

Nasturcia, Student (Russia)

Irina Nemtseva, Freelance artist (Russia)

Francesco Brusa, Journalist (Italy)

Viktoriia Iakusheva, Dance instructor (Russia)

Therese Caherty, Retired (Ireland)

Olga S., Translator (Russia)

Ksenia, Feminist (Russia)

Sophie Lewycky, Student-at-law (Canada)

Adriana Qubaiova, Academic (Czech Republic/Palestine)

Martyna Jałoszyńska, Razem (Poland)

Daria Gvozdeva, IT (Russia)

Michał Gocałek, Union lawyer/Marxist (Poland)

Val Graham, Political activist (UK)

Mario Bianco, Humanitarian aid worker (Italy)

Karina Tereshenko, Feminist (Russia)

Sonya, Artist (Georgia)

Genia Deriabina, Blogger, philologist (Russia/UK)

Benedicte Mey, Guebwiller citizen collective (France)

Anastasia, Student (Russia)

Anda Pleniceanu, Writer, researcher (Spain)

Marta, Womens’ rights activist (Poland)

Ian Ross Singleton, Writer, educator, Asymptote Journal (USA)

Barbara Łomnicka, Telecom (Poland)

Margaret Elwell, Assistant Professor of Peace Studies, Bethany Seminary (USA)

Evgenia Bragnikova, Feminist (Netherlands)

Renier, Teacher, film director (France)

Elissa Bemporad, Professor of History, City University of New York (USA)

Mr Jim Monaghan, Retired (Ireland)

Tamara Krawchenko, Assistant Professor, School of Public Administration, University of Victoria (Canada)

Sara Szerszeń, Student (Poland)

Mara Polakova, Translator (Latvia)

Paulina Kewes, English literature (UK)

Natalya Sukhonos, Professor (USA)

Oleksandra Tarhanova, PhD, Assistant Professor and research assistant at University of St Gallen, feminist, social scientist (Switzerland)

Federico Fuentes, Journalist (Australia)

Marina Skalova, Writer, literary translator (Switzerland)

Verena Irrgang, Rebel With Code – Feminist Hacker Collective (Germany)

Cynthia Lawson, Mental health worker (Australia)

Eugenia Benigni, International gender and social inclusion expert and activist (Italy)

Mila, Student (Russia)

Artem Kotov, Linguistics, English language teaching (Russia/USA)

Carol Mann, Women in War (France)

Patrycja Figarska, Human relations manager (Poland)

Ekaterina Molodec, manager (Russia)

Natalia Skoczylas, Antiviolence and antidiscrimination activist (Poland)

Katarzyna Augustynek, Intersectional feminist (Poland)

Zdravka Todorova, Professor of Economics (USA)

Connie Zukiwski, Wardhaugh, N/A (Canada)

Anthony Boynton, Teacher (USA/Colombia)

Aida A. Hozić, Associate Professor, International Relations (United States)

Mariya Mykhaylova, Psychotherapist (USA)

Natalia, Artist (Russia)

Colleen Payne, IT (Canada)

Kristen Ali Eglinton, Applied ethnographer and feminist researcher; co-founder and director of the Footage Foundation (USA)

Hélène Elouard, Feminist, éditrice (France)

Tanika Sarkar, Historian (India)

Govinda Rizal (Nepal)

Karine Berny, Artiste (France)

Pierre Vanek, Deputy for Ensemble à Gauche, Geneva (Switzerland)

Meghan Keane, Syria Solidarity NYC and Ukraine Socialist Solidarity Campaign member, New York (USA)

Maciej Bochajczuk, Journalist (Belgium)

Francine Sporenda, Révolution féministe (France)

Inna Ludman, Nurse (Russia/Israel)

Alena Ivanova, Feminist, migrants rights campaigner and organiser (UK/Bulgaria)

Birgit Poopuu, International Relations (Estonia)

Yakubovska Eva, Board member at Vitsche e.V., Berlin (Germany)

Anna Górska, National Board of Razem (Poland)

Marianne EBEL, Feminist Asylum, Marche mondiale des Femmes/Global Women’s March, Collectif neuchâtelois de la grève féministe/Feminist strike Neuchâtel collective (Switzerland)

Tetyana Lokot, Associate Professor, Dublin City University (Ireland)

Organisations

Coletivo Juntas! Brazil

Collectif vaudois de la Grève féministe, Switzerland

Young Feminist Europe, Pan-European

Equality Bahamas, The Bahamas

Love Care Home, Women and child rights activism (India)

Center for Empowering Refugees and Immigrants, mental health and social services for refugees and immigrants (USA)

Feminist Fightback, Anticapitalist Feminist Collective (UK)

Where Are The Women, Gender Sensitisation Training (India)

Union Syndicale Solidaires (France)

Fédération SUD éducation (France)

European Network for Solidarity with Ukraine (Belgium)

Warszawski Strajk Kobiet/Warsaw Women’s Strike (Poland)

CLARA International Feminist Collective (Czech Republic)

Spatium Libertas AC (Mexico)

Koster/Fire, Feminist initiative group (Russia)

Vitsche e.V., Civil society movement, Berlin (Germany)

Sign the manifesto

The list of signatures will be gradually updated

Cover: Kateryna Gritseva

We stand in solidarity with the people of Ukraine, fighting a brutal invasion by Putin’s Russia. We wish their people’s resistance victory over this criminal aggression.

We stand in solidarity with the people of Ukraine, fighting a brutal invasion by Putin’s Russia. We wish their people’s resistance victory over this criminal aggression.

The global peace movement has in general an admirable history of opposing wars that have caused so much suffering over the years. Activists have championed peace and social justice from Vietnam to Central America to Iraq, helping teach the world that in place of death and destruction, xenophobia and intolerance, we can work to resolve conflicts peacefully while devoting our efforts to meeting real human needs. The peace movement has long pointed out the gargantuan waste represented by spending on war. If all the money spent on weapons of death had been redirected towards human needs, poverty and hunger could have been wiped out long ago.

The global peace movement has in general an admirable history of opposing wars that have caused so much suffering over the years. Activists have championed peace and social justice from Vietnam to Central America to Iraq, helping teach the world that in place of death and destruction, xenophobia and intolerance, we can work to resolve conflicts peacefully while devoting our efforts to meeting real human needs. The peace movement has long pointed out the gargantuan waste represented by spending on war. If all the money spent on weapons of death had been redirected towards human needs, poverty and hunger could have been wiped out long ago.

The Feminist Initiative Group

The Feminist Initiative Group

The New York City United Federation of Teachers (UFT) is currently beginning negotiations over its contracts for its various titles, including teachers, counselors, social workers, paraprofessionals, and more. These contract negotiations come amid one of the most difficult years (and series of years) for educators in NYC’s public schools. Educators, like all Americans, face an economy rife with inflation. They have been forced to work without remote options despite many legitimate concerns about health and safety. They work with students who have struggled to academically and emotionally transition back from online to physical classrooms. Newer educators in the UFT have seen the erosion of protections and benefits for years, while retired members were recently upset with the possibility of increasing costs and difficult choices to make in the newly proposed, semi-private Medicare Advantage healthcare plan. The majority of retirees demanded out of the plan, a judge paused it, and the UFT leadership backtracked its support. Across the union, many rank-and-filers see the UFT as more or less another bureaucratic apparatus above them instead of as a mobilizing force that they can organize with to fight for what they need.

The New York City United Federation of Teachers (UFT) is currently beginning negotiations over its contracts for its various titles, including teachers, counselors, social workers, paraprofessionals, and more. These contract negotiations come amid one of the most difficult years (and series of years) for educators in NYC’s public schools. Educators, like all Americans, face an economy rife with inflation. They have been forced to work without remote options despite many legitimate concerns about health and safety. They work with students who have struggled to academically and emotionally transition back from online to physical classrooms. Newer educators in the UFT have seen the erosion of protections and benefits for years, while retired members were recently upset with the possibility of increasing costs and difficult choices to make in the newly proposed, semi-private Medicare Advantage healthcare plan. The majority of retirees demanded out of the plan, a judge paused it, and the UFT leadership backtracked its support. Across the union, many rank-and-filers see the UFT as more or less another bureaucratic apparatus above them instead of as a mobilizing force that they can organize with to fight for what they need.

Sri Lanka is part of a line of exceptional cases of sovereign default over the past several decades. Like Argentina in 2001 and Greece in the aftermath of the 2008 global financial crisis, the country is experiencing tremendous political upheaval as it deals with the consequences of a balance of payments crisis. In Sri Lanka’s case, this has made it difficult to repay its external debt denominated in dollars. But Sri Lanka’s crisis is also singular in the extent to which it reflects the issues of a contemporary global order on the verge of breakdown. As many commentators have pointed out, external shocks, from the Covid-19 pandemic to the war in Ukraine, have created unprecedented pressures on Sri Lanka as well as other countries in different parts of the global South. These shocks exposed Sri Lanka’s internal vulnerabilities. The latter are both structural, in terms of the country’s overwhelming dependence on the external sector, and political, because of the profound failure of the government led by President Gotabaya Rajapaksa.

Sri Lanka is part of a line of exceptional cases of sovereign default over the past several decades. Like Argentina in 2001 and Greece in the aftermath of the 2008 global financial crisis, the country is experiencing tremendous political upheaval as it deals with the consequences of a balance of payments crisis. In Sri Lanka’s case, this has made it difficult to repay its external debt denominated in dollars. But Sri Lanka’s crisis is also singular in the extent to which it reflects the issues of a contemporary global order on the verge of breakdown. As many commentators have pointed out, external shocks, from the Covid-19 pandemic to the war in Ukraine, have created unprecedented pressures on Sri Lanka as well as other countries in different parts of the global South. These shocks exposed Sri Lanka’s internal vulnerabilities. The latter are both structural, in terms of the country’s overwhelming dependence on the external sector, and political, because of the profound failure of the government led by President Gotabaya Rajapaksa.

Let me start with a childhood memory. My father was Tamil, my mother was Burgher – that’s what they call people with European ancestry in Sri Lanka – and we were living in a predominantly Sinhalese neighborhood just outside Colombo. One day in May 1958 our Sinhalese neighbor Menike, who was like a member of our family, came over in great distress, insisting that we leave our home at once and go somewhere safe because a bloodthirsty mob was heading our way. At around the same time my mother’s former student Yasmine, who had become a family friend, also Sinhalese, came over in a car, offering to shelter us at her parents’ place. My mother had been for a walk so my parents knew that Tamils were being attacked, but at that point they refused to leave. They packed off my brother and me and our Tamil grandmother in a taxi with another Sinhalese neighbor to stay with our burgher grandmother, and started making Molotov cocktails to defend themselves and their home. By this time Menike was frantic and threatened to commit suicide unless they left. They finally agreed, and yet another Sinhalese neighbor drove them in his car to Yasmine’s parents’ place.

Let me start with a childhood memory. My father was Tamil, my mother was Burgher – that’s what they call people with European ancestry in Sri Lanka – and we were living in a predominantly Sinhalese neighborhood just outside Colombo. One day in May 1958 our Sinhalese neighbor Menike, who was like a member of our family, came over in great distress, insisting that we leave our home at once and go somewhere safe because a bloodthirsty mob was heading our way. At around the same time my mother’s former student Yasmine, who had become a family friend, also Sinhalese, came over in a car, offering to shelter us at her parents’ place. My mother had been for a walk so my parents knew that Tamils were being attacked, but at that point they refused to leave. They packed off my brother and me and our Tamil grandmother in a taxi with another Sinhalese neighbor to stay with our burgher grandmother, and started making Molotov cocktails to defend themselves and their home. By this time Menike was frantic and threatened to commit suicide unless they left. They finally agreed, and yet another Sinhalese neighbor drove them in his car to Yasmine’s parents’ place.

The Russian invasion of Ukraine caught most observers by surprise. I, for one, didn’t think that the Russian government would be so foolish as to invade. If Ukraine resisted, the Russian military could destroy it with nuclear weapons but couldn’t conquer it with the conventional forces they had deployed to its borders. The Russian ruling class needed a deal, not a war. Ukraine in the European Union and out of NATO, like Finland or Sweden, would have suited it very well. The Russian people certainly didn’t want war.

The Russian invasion of Ukraine caught most observers by surprise. I, for one, didn’t think that the Russian government would be so foolish as to invade. If Ukraine resisted, the Russian military could destroy it with nuclear weapons but couldn’t conquer it with the conventional forces they had deployed to its borders. The Russian ruling class needed a deal, not a war. Ukraine in the European Union and out of NATO, like Finland or Sweden, would have suited it very well. The Russian people certainly didn’t want war.