Declaration of the Rights of Man and Citizen

Vladimir Putin’s Russian war against Ukraine has raised the question of the meaning of “Western values.” We look here at such values, asking if the socialist left supports them, and if so, to what degree.

The foreign policy of the United States and of Western European countries is often decided and carried out in the name of the “defense of Western values.” The slogan is used to justify U.S. and European arms buildups, troops deployments, and wars in various parts of the world. At the moment, U.S. and European aid to Ukraine is couched in terms of “Western values.” Spokespeople for Western governments typically talk about defending democracy, the rule of law, and the liberal state, counterposing those to governments that are repressive, authoritarian, or totalitarian.

These are not new arguments. They were made at the time of World War I to contrast Europe’s democratic states—which were also the great imperial power—Great Britain, France, Holland and Belgium with Prussian militarism. The democratic states, however, were allied with Tsarist Russia, “the prison house of nations” and “land of the knout,” as it was called. Only after Russia’s revolution overthrowing the Tsar in February 1917, did Woodrow Wilson led the United States into that war supposedly fought for democracy.

During World War II, once again Western European nations were characterized as democracies—ignoring their millions of colonial non-citizens—and contrasted with Adolf Hitler’s Nazi Germany, Benito Mussolini’s Fascist Italy, and the Japanese monarchy and military dictatorship. With the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, the United States joined the Allies. Later, however, those democratic states ruling great empires of subjugated colonial peoples allied with Joseph Stalin’s totalitarian Soviet Union.

Once again, we hear this argument, now from Ukraine’s president Volodymyr Zelenskyy who has repeatedly stated that his country is the frontline in the battle of democracy against the authoritarianism and imperialism represented by Vladimir Putin’s Russia. Zelensky claims to stand for “Western values,” above all democracy. The support for Ukraine from the United States and European nations is predicated upon that claim.

Where does the Left stand and where should it stand on this question of “Western values”? Some on the Left argue that all the talk of Western values is simply propaganda used to justify Western imperialism. These Leftists not only reject the talk of Western values abroad but often also argue that these values have little significance at home either. The United States and Western European nations, they say, are not really democracies at all; for these leftists, there is not much difference between Trump and Biden or between France and Hungary. And these leftists argue, the claim to defend democracy in other nations is simply a swindle, a ploy often used to depose unfriendly governments and install others more friendly to U.S. business interests and geopolitical designs. There is no doubt a good deal of truth in the latter statement. But is that all there is to it?

The purpose of this essay is to lay out a clear position of where the Left should stand on the question of the defense of Western values. I will make the case here that: First, there are many Western values worth defending, though clearly others that should be rejected. Second, we also have to acknowledge that some of what historically began as Western values spread around the world and became universal values. Third, we should recognize that there are also other values that arose in other places, equally important themselves, that are also worth defending. Fourth, we examine the Left’s stake in Western, universal values.

The Left’s Historic Defense of Western Values

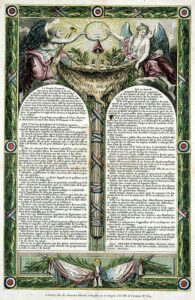

The very notion of the Left itself—that is communities, movements, and institutions committed to the combination of democracy and socialism—is itself, of course, a Western value, so we might start there. We don’t have to recapitulate here the history of the origin of Western democratic institutions in ancient Greece, in the medieval communes, or in the bourgeois revolutions of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. Those revolutions in Holland, England, France, and the United States superseded monarchic and aristocratic rule and eventually replaced the divine right of kings with the notion of the bourgeois republic: Government by elected representatives of the wealthy classes, landowners and businessmen—a democratic republic would only come later. The French Revolution of 1789 also gave us The Rights of Man while the American Revolution of 1776 led to The Bill of Rights, both expressing the idea of equality before the law and of fundamental civil liberties. Here, for example, is Article VI of the Rights of Man:

The law is an expression of the will of the community. All citizens have a right to concur, either personally, or by their representatives, in its formation. It should be the same to all, whether it protects or punishes; and all being equal in its sight, are equally eligible to all honors, places, and employments, according to their different abilities, without any other distinction than that created by their virtues and talents.

This remarkable statement represented a profound and absolute break with the monarchical, hierarchical governments that had come before.

The U.S. Constitution’s Bill of Rights established fundamental democratic rights such as freedom of assembly, of speech, and of the press; the right to petition the government; freedom from arbitrary search and seizure; and habeas corpus. Achieved through revolution and breaking with the past of feudalism, these bourgeoise republics represented a significant advance over autocracy and their civil liberties not only protected citizens from arbitrary treatment, but created the legal framework for struggles for extending democracy. The bourgeois republic and its parliament system presupposed the existence of rival political parties that would put forward to the people different political programs. Such a republic, holding periodic elections, would be open to a change of political direction reflecting the voters’ desires.

We should not overlook an even more basic and foundational right, that is the right of a people to form a nation, a republic, and to protect its independence and sovereignty. Sometimes, as in France, these nations were formed through the overthrow of a monarchy that existed in more or less the same territory. In other cases, in the nineteenth century such as those of the United States and the nations of Latin America, the new countries were formed by separation from an empire that had previously controlled them. The same was true of the nations that in the twentieth century arose from the fall of the Austrian-Hungarian empire, the Ottoman empire, and later those that won independence from the British, French, and Dutch empires. Similarly with the nations freed by the fall of the Soviet empire. The right of national self-determination, the right of a people to create a nation of their own, forms the basis for the creation of a republic and the establishment of civil liberties.

All of that was part of a broader process. We often talk about a double revolution in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, because the rise of the bourgeois republics was accompanied by the rise of industrial capitalism. This parallel rise of capitalism within the first European republics, that is, the development, growth, and rise of the bourgeoisie accompanied by the arrival and progress of the working class created the possibility of fighting within those capitalist republics for the right of all men—and later of all women too—for their right to vote for their representatives and to change the course of government. The struggle for popular democracy was based in large measure upon the existence of the bourgeois republics, of equality before the law, and of civil liberties: the right to assemble, to speak, to publish, and to petition the government. At the time, neither republics nor civil liberties existed outside of Western Europe and North America, so those came to be thought of as “Western values.”

We should note that other regions failed to create democratic institutions with civil liberties from ancient times to the twentieth century. In India the hierarchical and racist Hindu caste system created enormous obstacles to democracy or any sense of equality. In China Confucianism became the philosophical justification for an authoritarian, and hierarchical, bureaucratic state and society. And when the old Chinese empire decayed, it became rife with warlords. In Japan, emperors or shoguns, military rulers, held power; there was no popular democracy. In Africa, kings ruled in many regions, though sometimes their power often restrained by older communal institutions. In pre-Columbian Latin America, military or theocratical leaders—Mayan, Aztec, Incan, and others—ruled throughout the continent. Then the Spanish and Portuguese conquerors imposed their monarchies and aristocracies on the colonies.

In all of these societies some more egalitarian local communities existed and there were, from time to time, rebellions from below, but the people in those regions never succeeded in creating republics or civil liberties. The rise of democratic values in Europe is not due to anything biologically superior or special about the European peoples as compared to the Asians, Africans, or Latin Americans, but is rather to be explained by the particular geographical and historical conditions that arose in Europe creating higher productivity of agriculture and animal stock, then an accumulation of technology leading to increased commerce and wealth accompanied by new forms of social organization, and finally the rise of new social classes, namely the bourgeoisie and the working class, who created new values. Later, through imperial conquest, capitalist commerce, or imitation, other regions did develop democratic institutions, bourgeois democracy with all of its contradictions and possibilities.

While bourgeois democracy and capitalism arose at the same time, the two were from the beginning in conflict with each other. The bourgeoisie controlled the state and used it to protect its property and the capitalist system, while the working classes demanded that the state protect their interests, that it give them the right to vote, establish a shorter work day, and provide education for their children. Using their rights won in the course of the bourgeois revolutions—assembling and protesting, speaking, and publishing—by the mid-nineteenth century groups of workers in Europe created labor unions and peasant leagues, founded labor and socialist parties, engaged in strikes, held protest demonstrations, practiced civil disobedience, and eventually succeeded in winning the franchise and electing their representatives to parliament.

The rise of the labor and socialist movements, frustrated by the capitalist state’s refusal to meet its demands for democracy and for popular power as well as a better life, led to powerful reform movements such as the Chartists in England and to revolutionary outbursts such as the attempted socialist revolution in France in June 1848, struggles that combined the fights for democracy with workers’ demands for political power. In several countries in Western Europe over hundreds of years of struggle working people won both greater democracy and civil liberties. In the United States the Civil War of 1861-65 led to amendments that constituted a new constitution, with Articles 13, 14, and 15, freeing the country’s slaves, giving them citizenship and the right to vote (all later jeopardized by Jim Crow, disfranchisement, and lynching, but a real achievement none the less). The idea of democracy and the greater freedom that working people had won through the exercise of their civil liberties, allowed them in the nineteenth century to conceive of a democratic collectivization of the economy, that is, of democratic socialism. So, at the end of World War I in 1918 there were several attempts at socialist revolutions in Russia, Germany, Bavaria, and Hungary.

All of this that I’ve described can be called a constituent part of Western values: a democratic republican government made up of elected representatives and a population enjoying civil liberties, making possible social protest, revolts, and even revolution. Every socialist party of the nineteenth and early twentieth century inscribed on its banner the demand for a republic, democracy, and civil liberties. All of the major Marxist thinkers—Marx and Engels, Luxemburg and Lenin, as well as Trotsky—stated their belief in a democratic representative government and civil liberties as essential to the fight for socialism and integral to a future socialist society.

The Western Values We Do Not Defend

We on the Left do not, of course, defend all Western values and institutions. The bourgeois republic was from its inception a problematic institution to say the least. The democratically elected government tended to become the “executive committee of the ruling class,” as Marx called it. Parliament and government tended to be dominated by landlords and capitalists, because they had the time and money, controlled the newspapers and later other media. Their chambers of commerce and industry, their banks and stock markets, financed candidates and installed their representatives in Congress who passed laws to protect their financial interests; at the same time, the capitalist class, which tended to have the most influence in government, generally obstructed the passage of laws that would have benefitted peasants, workers, or the poor. The capitalists’ laws and the violence that enforced them protected private property, insured the right of capital to exploit labor, and created the political structures, social organization, and the legal context for the accumulation of capital. These states at the same time enacted laws and established practices that preserved class, gender, ethnic, and other inequalities and deepened them, often virtually eradicating the notion of equality before the law.

The Western bourgeois republic, that is to say, the capitalist state, evolved by the late nineteenth century into a monstrous institution with large police forces used to suppress the working class, peasantry, and the poor, with armies used to conquer foreign colonies in Latin America, Asia, and Africa, and with navies that controlled the seas and protected the empires and their international commerce. The imperial states beat, imprisoned, and sometimes killed workers at home—sometimes by the scores or even hundreds—and engaged in massacres of millions in the colonies (ten million in the Belgian Congo alone). At the time, much of the Left rejected the capitalist system and sought through parliamentary means to take control of the state for the working class. Socialists and feminists in Europe and America continued to fight for the franchise, for the right of all adults, both men and women, to vote.

When the opportunity presented itself, working people, acting outside of the parliamentary system, attempted to take power for themselves and to create a workers’ republic. After the most important such attempt in the nineteenth century, the Paris Commune of 1871, Marx had concluded that the state could not be taken over as it was and used by the working class, but that would it would have to be destroyed (“smashed,” he said) and replaced by a workers’ state, believing that the new workers’ state would be some sort of democratic republic. Yet, even in the era of the modern capitalist, imperial state, an era of savage capitalism, in Western Europe until the 1920s and 30s, democratic institutions continued to exist: elected parliaments and constitutions that protected basic civil rights such as free speech, free press, and assembly. The Left, reformist and revolutionary, defended those institutions as central to the fight for socialism and through class struggle, in many countries workers won significant reforms that improved their working and living conditions.

The Decline of Western Values: Communism, Nazism and the Left

The great leftist figures of the twentieth century, Lenin, Luxemburg, and Trotsky, argued that a socialist revolution would expand the working class’s power, establish democratic institutions and enhance and augment peoples’ rights. During the Russian Revolution of 1917 led by Lenin’s Bolshevik Party (later the Communist Party), there was briefly an upsurge of the existing labor unions and new political parties, some groups fought for workers direct management of their workplaces and industry, and new democratic institutions were created, such as the soviets or workers’ councils, constituting at first a workers’ republic. Under the early Soviet government women’s rights were recognized and discrimination against Jews and other groups prohibited. And Lenin argued for the right to self-determination for Russia’s colonies and subject peoples.

Yet for reasons that have often been discussed—economic backwardness, the world war and civil war, foreign invasions, and political isolation, as well as the Bolshevik’s own policies—democracy and civil liberties soon disappeared. In the early 1920s, the Bolsheviks, now called the Communist Party, established a one-party state that took control not only of the government, but of the entire economy, of the soviets, of the labor unions, and of all other popular organizations. Wars fought to defend the new state led to militarization of the society and the creation of a secret police (CHEKA, NKVD, GPU, KGB) that became a powerful force. By the late 1920s, Joseph Stalin emerged not only as the head of the party and the state, but as dictator. In the struggle to impose his domination and to create a new bureaucratic state in the Soviet Union, Stalin carried out a thorough going counterrevolution, killing tens of thousands of political opponents and imposing policies that killed six million or more peasants. Western values—if that meant democracy and civil liberties—were never established in the Soviet Union and what little was achieved was destroyed by Stalin.

At the same time, the crisis of capital in the early twentieth century, the Great Depression and widespread political instability, led to the increasing decay of republican institutions in Western Europe, the rise of Fascism in Italy and Nazism in Germany, and then to the collapse of vaunted Western values, the destruction of democracy and the abolition of civil liberties. Hitler and Mussolini, as opponents of democracy and socialism, took political power in collaboration with sections of the capitalist class. They did not nationalize the economies of their countries, preferring to use their political power to subordinate finance and industry to their imperial agendas. One-party states were created, other parties were banned, labor unions were transformed into labor fronts with workers subordinated to capital. Opponents of the regime, bourgeois or leftist, both Social Democrats and Communists were imprisoned. Ethnic minorities were ghettoized and terrorized, followed by the Nazi holocaust and the murder of millions of Jews, Roma, Poles, Ukrainians and others who were considered Untermenschen, racially inferior. Needless to say, equality before the law, civil rights, and democracy were utterly eradicated. Over the years, many scholars have pointed to the similarities between the Nazi and Communist states, and some have referred to both Stalinist Russia and Nazi Germany as something like feudal societies and to Stalin and Hitler as the virtual monarchs. Be that as it may, many agree that both were totalitarian societies and both men dictators who abolished democracy and erased civil liberties.

From Western Values to Universal Values

The capitalist system—global from its beginnings—had become ever more integrated on a world scale in the nineteenth century. England, France, Holland and other European nations established empires with far-flung colonies in Africa, Asia, and Oceania. These empires not only brutally murdered many of the indigenous peoples but also established virtual enslavement of those they conquered. The spread of capitalism was not accompanied by the spread of parliamentary democracy or civil liberties; in most colonies the people had virtually no rights. But in that imperial era, through colonial schools, newspapers, and books, Western values—including the idea of socialism—reached and inspired many of the leaders and activists of the anti-colonial movements. In some of those colonies, working people recapitulated the history of European working people, creating labor unions, socialist parties, and fighting for democratic republics and civil rights. At the end of World War II, with many of the colonies seething with discontent and others in open rebellion, the European empires gradually collapsed. Many of the newly independent nations established republics and adopted constitutions that guaranteed civil liberties. Western values of democracy and civil liberties had become universal values.

Bourgeois democracy was on the march in the late 1940s. In Europe, with the victory of the allies and under the pressure of the Allies, the Nazi government of Germany and the Fascist government of Italy were dismantled and bourgeois democracies reestablished. In Asia, the U.S. government dethroned Japan’s emperor, dismantled the country’s military government, and wrote a new constitution that imposed a bourgeois democracy. In 1948 the newly established United Nations adopted the Universal Declaration of Human Rights that included not only the civil liberties that had been proclaimed a century and a half before in the Declaration of the Rights of Man, but also many social rights. For example, it declares:

Everyone has the right to work, to free choice of employment, to just and favorable conditions of work and to protection against unemployment. Everyone, without any discrimination, has the right to equal pay for equal work. Everyone who works has the right to just and favorable remuneration ensuring for himself and his family an existence worthy of human dignity, and supplemented, if necessary, by other means of social protection. Everyone has the right to form and to join trade unions for the protection of his interests.

While the United Nations has never had the capacity and its member nations never had the desire to enforce these rights, the U.N. having them adopted established a certain global standard to which we could aspire.

At the same time most of the newly independent former colonies also adopted these values. When India won its independence in 1947 it established a democratic constitution. Similarly with the former Dutch colony of Indonesia in 1949. In that post-war, post-colonial period democratic institutions were adopted by many nations in Asia and Africa. Western values became enshrined in constitutions and pervaded popular consciousness in much of the East and the Global South. Western values had become universal values. As we know, the reestablishment of bourgeois republicans in Western Europe meant the development once again of the contradictions between capitalism and democracy, often to the detriment of the latter. And in the former colonial world, many new independent nations became economic colonies dominated by the former imperial powers. Many such countries were only nominally democratic and some soon gave up even the appearance, some becoming dictatorships. Nevertheless, their constitutions had established a certain aspirational ideal toward which their people could aspire. When they existed in the Global South, democratic republics and civil liberties made it possible for working people to fight for power and to struggle to improve their lives.

The big exception to the adoption of these universal values of democracy and civil liberties in the post-war period was China. In China Mao Tse-tung’s Communist Party led a vast peasant army to victory against both Japan and the rightwing nationalist Kuomintang party. The Chinese Communist Party established a one-party state modeled on the Soviet Union of Joseph Stalin and also revived Confucian authoritarianism. Consequently, there was neither political democracy nor civil liberties, so that Mao and his party were able to hold on to power for decades, even as their policies led to disaster, with 45 million starved to death in the Great Famine of 1959-61 and a million more dead in the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution. When the Chinese Communist elite decided in the twenty-first century to adopt many capitalist practices, workers and peasants at first resisted, but without democratic rights soon succumbed.

Progressive Values from the Non-Western World

Our socialist values are not all Western, nor are they static. There is no doubt that other regions of the world with other civilizations and cultures have also contributed to the contemporary Left’s conception of important values. Throughout the world, pre-industrial societies often had at their base communal and collective institutions that we have come to value, though in their own regions and countries they were often subordinated to authoritarian and oppressive states that had in turn become subordinated to various empires and to the world market. One thinks of the democratic communal councils and collective land ownership and management of indigenous societies in Latin America, such as the ejido of Mexico, though one has to recognized these councils often excluded women and were frequently dominated by some clique or individual. Marx in his ethnographic notebooks examined and admired the democratic character of the confederation of the Iroquois. He recognized the potential of such institutions in his writing about the Russian mir and obschchina as a possible model for a transition in such societies to democratic socialism.

We on the left certainly embrace and defend these sorts of institutions when they are modernized and transformed, as in some cases they have been, to include women, as the Zapatistas claim to have done in Chiapas, Mexico. We can well imagine such institutions and practices forming part of progressive social movements and helping to construct future socialist societies.

Similarly in industrial societies all over the world, other institutions arose out of working-class experience, such as workers cooperatives that engaged in what is sometime called autogestion or self-management of the workplace. These workers too created councils in which all might participate and make decisions about their workplace democratically. Many conceived of this cooperative, autogestionary work as a contribution toward the establishment of socialism.

The Contemporary Conception of Universal Rights

Western values became universal values that today encompass more than parliamentary democracy and civil liberties, civil rights and labor rights. Cooperativists and the workers self-management movements in many parts of the world have enriched our conception of democratic values with the notion of workers’ control of production. People of color, feminists, and the LGBTQ+ movement, all fighting for equality, have enriched our conception of freedom, establishing the notion of the right of each human being to be able to give full expression to their ethnic and gender identity. We have through the women’s, LGBTQ, and trans rights movements come to have a greater appreciation of the importance of personal self-determination and decision making. Today everyone left of center understands that a country where people of color, women or LGBTQ+ people are not fully equal is not a free and democratic. At the same time, the environmental movement, with its concern for the future of the planet and all of the life on it, including human life, has also enriched our conception of human values to include protection of the earth. Environmentalists have also given us a greater understanding and appreciation of the role of indigenous people in protecting nature in all of its variety. All of these have become part of our universal democratic and socialist values.

While some on the left reject the idea that Western values have any worth, they must surely recognize that countries without these values, such as Russia and China do not be permit their citizens to engage in any of the political activities that those on the left are able to pursue in democratic countries. China doesn’t permit any criticism of the government and Russia doesn’t permit any opposition protests. In Russia human rights activists may be jailed and in China independent labor organizations have been shut down. Russia is engaged in a genocidal war to eliminate Ukraine and to erase the Ukrainian identity, while China has rounded up and put in concentration camps 1.8 million of the 12 million Uyghur and is pursuing cultural genocide against them by eradicating their ethnic identity. What would such Leftists—who here in the United States often fight for Black and Latinx and other minority rights and who work to organize workers into labor unions—do in Russia or China? I fear that they would very likely find themselves arrested, convicted, and sent to prison to sit and wonder how they got things so wrong, how they didn’t recognize that China and Russia have their own repressive state, their own exploitative social systems, and their own imperial agendas.

There is no doubt that Western values of democracy and civil liberties are in crisis today in the West and throughout the world because of the rise once again of rightwing movements, parties, and politicians in the United States, France and Germany, and of anti-democratic and authoritarian governments not only in Hungary, but also in Turkey and India, and in Nicaragua, Venezuela and Brazil. Then too there are the totalitarian governments—with varying degrees of repression—in Russia, China, North Korea, and Cuba where no opposition parties, no independent unions or social movements, and no expression of political opposition is permitted. The question then arises, are we leftists for the defense of democratic governments and civil rights?

We recognize, of course, that we are talking about very imperfect democracies, such as the United States where corporations dominate the Congress, rightwing politicians’ control about half of the state houses and legislatures, where the exploitation of workers has become ever more intense, and where Black and Latino people face mounting racism and repeated instances of racist police violence. Still, we know that in our imperfect democracies in the United States and Europe, as well as in some countries in Latin America, Africa, and Asia, we still have the possibility of exercising some influence over our governments—even of changing the political party in power—and of defending our civil rights and liberties, thus giving us the opportunity to organize social movements against racism and sexism and to organize labor movements to fight to improve workers’ conditions and struggle for socialism.

The Left and the U.S. Government

What does it mean that some of us on the left coincide with one or another capitalist politician and party on the question of the defense of bourgeois democracy? While we defend the same institutions, the democratic republic, equality before the law, and civil liberties and rights, we have very different interests. They defend those institutions because they wish to use them to perpetuate capitalism, with its banks and corporations, and with the attendant system of exploitation and oppression under which we now live, because the system benefits them. We, on the other hand, defend those democratic institutions and practices for utterly different and absolutely counterposed reasons, because we recognize they are key to the fight for a democratic socialist society. Our Bill of Rights allow us to speak and publish, to criticize and petition, to assemble and to protest, and all of that makes possible our struggle for workers power and socialist revolution. All of this, of course, as long as a reactionary Supreme Court doesn’t take them away.

When we on the left happen to coincide with the capitalist class or the government, does that mean that we support the U.S government? No. We can see that the U.S. government often doesn’t defend democracy or civil rights here at home, and frequently encroaches on them. The preservation of democracy in the United States and other countries depends on working people’s constant vigilance, mobilization, and confrontation with the state. But the existence of democratic institutions, however flawed, and of civil liberties, however deficient, make it possible for us to fight against the banks and corporations, against the government, and for social justice, workers power, and socialism.

If it does a poor job of defending democracy at home, the U.S. government’s foreign policy is even more egregious. Since World War II, the United States has puts itself forward as the leader of what it called the Free World, but after 1945 that world included fascist Spain and Portugal and numerous Western-backed dictatorships in Latin America and the Caribbean, Asia, Africa, and the Middle East. In its 75 years as leader of the so-called “Free World” the United States fought the Vietnam War that led to the death of more than two million people in South East Asia and the United States has overthrown democratic governments in Iran, Guatemala, and Chile, just to name a few, replacing them with more pliable regimes. The U.S. wars on Afghanistan and Iraq—for geopolitical supremacy and control of petroleum—took hundreds of thousands of lives. The full list of America’s anti-democratic interventions is too long to go into here. Today the United States is allied with Saudi Arabia, a reactionary theocratic monarchy led by King Salman who was responsible for the murderer of journalist Jamal Khashoggi and accountable for the horrific war and mass civilian deaths in Yemen. European nations such as France have their own long list of coups carried out to keep former colonies under their control. In the Global South, the United State is by no means the defender of the Western values or the universal values of democracy and civil liberties that it claims to be.

Despite that, one has to recognize that the people of the nations of Western Europe such as Sweden, France, or the Czech Republic enjoy far more democratic governments and more civil liberties than those of Russia, Belorussia, or Kazakhstan. Zelensky is correct when he says that Ukraine is defending Western values. While the Ukrainian government has serious problems—powerful oligarchs, corruption, and far right political movements—still it is far more democratic than Russia. Unlike Russia, Ukraine has rival politicians, competing parties, and alternative political platforms. In Ukraine—at least until Russia’s invasion— the media was largely if not entirely free to print and broadcast. The international working class and the left have every reason to support Ukraine as the frontline in the defense of freedoms that are now threatened in Western Europe.

At present, with Russian dictator Vladimir Putin waging war on Ukraine, the United States and European governments and capitalist classes by and large support Ukraine, as does and the internationalist, socialist left, but again for different reasons. The United States and the European Union wish to protect and expand the capitalist system, while Eastern Europeans fear Russia and want to stop its imperial expansion, and the Ukrainians fight to defend their country’s imperfect democracy, its leftist parties, and its labor unions. We on the socialist left also back Ukraine, but we support its democratic and social movements, and its labor unions. If we happen to coincide partially and temporarily with Western capitalism in defense of Ukraine, that represents no retreat from opposition to Volodymyr Zelensky’s neoliberal government and its anti-worker policies, nor to struggle against the country’s far right political organizations. Even while Ukraine fights against Russia, the class struggle continues within Ukraine.

The Question of NATO

What then about the question of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), the alliance of the United States and European nations founded in 1949? Is it a defender of Western values? Certainly, at the time of its establishment as a defensive alliance, NATO claimed to defend those value, the treaty’s preamble stating:

The Parties to this Treaty reaffirm their faith in the purposes and principles of the Charter of the United Nations and their desire to live in peace with all peoples and all governments. They are determined to safeguard the freedom, common heritage and civilization of their peoples, founded on the principles of democracy, individual liberty and the rule of law. They seek to promote stability and well-being in the North Atlantic area. They are resolved to unite their efforts for collective defense and for the preservation of peace and security. They therefore agree to this North Atlantic Treaty:

The founding members of NATO (Belgium, Canada, Denmark, France, Iceland, Italy, Luxembourg, Netherlands, Norway, Portugal, the United Kingdom, and the United States), were, with the exception of fascist Portugal, all bourgeois democracies. Several, however, were also imperial powers, colonial or neocolonial. And at the same time, as noted above, the United States was allied in other regions of the world with such autocracies as Saudi Arabia and in the 1950s and also organized coups to put compliant governments in place in Iran and Guatemala.

NATO was at its foundation clearly a U.S.-led bloc of capitalist governments and just as six years later the Soviet Union established the Warsaw pact, the bloc of Communist states (Albania, Bulgaria, Czechoslovakia, East Germany, Hungary, Poland, Romania, and the Soviet Union), though in that organization the Soviet Union was an imperial power dominating the others and not one of the Communist governments was a democratic republic and none had civil liberties. And when the people of those countries attempted to change their governments, as in Hungary in 1956, in Czechoslovakia in 1968, and in Poland in 1980, the Soviet Union either invaded as in the first two cases or supported a military clampdown as in the third.

With the fall of Communism and the Soviet Union in 1989-91, NATO might have been dissolved and some other regional security system devised, but the United States and the European nations saw NATO as a vehicle for expanding the West’s influence over former Eastern Bloc Communist nations and in 1995 began plans for expansion. While NATO reached out to Eastern European nations, it was those states that voluntarily decided to join, motivated by their own experiences of Soviet imperial domination for over fifty years. After Putin’s wars in Chechnya (1999-2000), Georgia (2008), and Ukraine (2014) demonstrating his imperial ambitions, the desire for the NATO shield grew stronger, as it has now again after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in 2022. Today Finland and Sweden have sought NATO membership, an attitude that is perfectly understandable and with which we can sympathize given the Russian war on Ukraine and these Nordic countries fear that they might be next on Putin’s list of future conquests.

Is NATO a defender of universal democratic values? Nearly all of the thirty NATO nations are democratic republics that recognize their citizens’ civil liberties, with all of the contradictions we have discussed that exist in all capitalist democracies. The two exceptions in NATO are Hungary and Turkey, authoritarian governments with heavily illiberal policies. Just as a matter of fact, on one side of the NATO line are Europe’s democracies, including Ukraine, and on the other the authoritarian governments of Russia, Belarus, and Kazakhstan. One is highly unlikely at this time to get a hearing in Eastern or Western Europe for the abolition of NATO. While NATO is not at war with Russia, NATO member nations are arming Ukraine. A majority of Europeans and many in other countries view NATO at this time as a bulwark against Russian aggression and the expansion of Putin’s authoritarian regime, much as many saw the Western democracies in the 1930s and 40s as they faced Hitler’s Nazi regime.

Some pacifists and some anti-imperialists, while condemning the Russian invasion, also oppose arming Ukraine and argue that NATO provoked the Russian invasion. Some socialists, looking back to the politics of Lenin and Trotsky at the time of the First World War, call for revolutionary defeatism among the nations of the NATO bloc and in Russia. We do not believe that either the pacifist or the Leninist slogans are appropriate for this moment in history. While we sympathize with the pacifists’ desire to end the violence, we believe the Ukrainians have the right to defend their national sovereignty and that we as socialists should stand by them. Today, with the left so weak, we do not believe that Lenin’s slogan—meant to turn war into revolution—is useful. We believe that we should stand with Ukraine against the Russian aggressor and support its getting arms wherever it can, while at the same time we stand for the eventual dismantlement of NATO. We should strive to replace NATO as soon as possible with an alternative international security structure where all nations in the region would feel secure and none threatened, ideally a system tending toward reducing troops and armaments.

The Future of Our Values

We on the left will have to continue to fight for these values that we cherish: democratic republics, civil liberties, racial and gender equality, workers’ rights, and care for the environment. We recognize that whatever democracy and civil liberties we enjoy were won by working people, and that working people will continue to be central to the struggle. We will defend bourgeois democracy, even while we fight the bourgeoisie, because we need democratic governments and civil liberties in order to organize unions, to create working class socialist parties, and to fight for socialism. And once we achieve socialism, we will need some sort of representative government and civil liberties in order to democratically govern a socialist society and ensure the rights of all.

Leave a Reply