Over 400 years ago, long before Woodrow Wilson or Vladimir Lenin, the Christian humanist Bartolomé de Las Casas, known as the “Defender of the Indians,” developed a theory of the right of nations to self-determination that can be applied to many other countries today, including Ukraine.

Over 400 years ago, long before Woodrow Wilson or Vladimir Lenin, the Christian humanist Bartolomé de Las Casas, known as the “Defender of the Indians,” developed a theory of the right of nations to self-determination that can be applied to many other countries today, including Ukraine.

Russia’s war on Ukraine, its former colony, has raised again the issue of “the right of nations to self-determination.” We commonly associate the phrase with two men and two documents of the early twentieth century: Vladimir Lenin’s book The Right of Nations to Self-Determination (1914) and Woodrow Wilson’s “Fourteen Points Speech” (1918).

Lenin’s book was intended to provide a program for the Russian Social Democratic Labor Party and a guide for a post-revolutionary Russian state. Lenin concludes his book with this paragraph:

Complete equality of rights for all nations; the right of nations to self-determination; the unity of the workers of all nations—such is the national program that Marxism, the experience of the whole world, and the experience of Russia, teach the workers.[1]

Wilson’s speech on the fourteen points was meant to counter Lenin’s position,[2] to lay the basis for ending World War I and negotiating a peace at Versailles that would weaken the European empires and open the way for a new sort of imperialism, an American imperialism without political control of colonies, an informal, economic empire. Wilson called for an independent Poland to be reconstituted from the German, Austrian-Hungarian, and Russian empires, and other alterations in the map of Europe. Regarding the European colonies in Africa, Asia, and Latin America, he wrote that there should be,

A free, open-minded, and absolutely impartial adjustment of all colonial claims, based upon a strict observance of the principle that in determining all such questions of sovereignty the interests of the populations concerned must have equal weight with the equitable claims of the government whose title is to be determined.[3]

President Woodrow Wilson delivers his “Fourteen Points” speech to Congress.

Wilson’s was talking about adjusting rival claims of the European empires, not liberation for the colonial peoples. Wilson suggests giving equal weight to the colonial Great Powers’ and diplomats’ notions of the colonies’ interests, but no one, including Wilson and the American government at that time was prepared to listen to the colonial peoples themselves and certainly not to grant them self-determination and national sovereignty. Wilson wanted an “open door”—into other nations’ empires.[4]

Lenin’s attempt after the Russian Revolution to create a federation of genuinely independent socialist states failed as Joseph Stalin led a counterrevolution and created a new Soviet empire. Wilson and the United States contributed to undermining European imperialism and gradually establishing a new informal American imperialism[5], though it took another World War to get there.

After World War the right of nations to self-determination was enshrined in Articles 1 and 2 of the United Nations charter, though frequently the principle was violated in practice by the United States as well as by other great powers.

Yet today, few are aware that more than 400 years before all of this the Spanish Dominican friar Bartolomé de Las Casa, in his book In Defense of the Indians, elaborated on the basis of Christian humanism a theory of the right of nations to self-determination as compelling as Lenin’s.

Las Casas’ book In Defense of the Indians, written between 1548 and 1550, was his contribution to the Valladolid Debates where his opponent was the theologian Juan Ginés de Sepúlveda. The debates were organized by Spanish King Charles V to determine how his empire should deal with its new American colonies and how it should treat the indigenous people of the Americas. At issue were the most fundamental questions: Were the indigenous people human beings? Did they have souls? Were they some lesser form of human beings? Were they “natural slaves”? Did they possess any rights? Did their nations have any rights? In the course of his argument, Las Casas argued for the humanity of the Indians and defended their right to self-determination (more about that below).

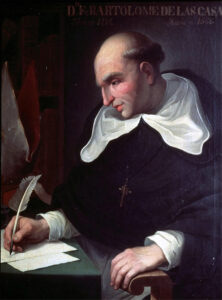

Fray Bartolomé de Las Casas

Las Casas: From Conqueror and Slave Owner to Priest Defender of the Indians

The debate is quite well known, of course, to students of Latin American history and has also been the subject of popular novels and film, but still warrants further discussion and dissemination.[6] There is no doubt that much of our interest in Las Casas that inspires novels and films is stirred by his extraordinary biography, his conversion from conqueror of Indians to their defender and his indefatigable work for fifty years defending both Indians and Africans in the Americas.

Bartolomé de las Casas was born in 1484 in Seville, to a French immigrant merchant family that had helped to found the city. One biographer believes his family were conversos, that is, Jews who had converted to Catholicism. As a child, in 1493 he happened to witness Christopher Columbus’ return from his first voyage to the Americas to Seville with seven Indians and parrots that were put on display. Queen Isabella ordered the Indians to be returned to their native land.

Bartolomé’s father, Pedro de las Casas, joined Columbus on his second voyage and brought home to Seville as a present for his son Bartolomé an Indian. In 1502 Pedro took Bartolomé with him on the expedition of Nicolás de Ovando to conquer and colonize Española (in English he island of Hispaniola, today made up of the Dominican Republic and Haiti). Bartolomé conducted slave raids on the Taino people (who were virtually annihilated by the Spaniards) and was rewarded with land and became the owner of a hacienda as well as slaves. In 1506 he returned to the University of Salamanca, where he had previously studied, and then traveled to Rome where he was ordained, becoming a priest in 1507.

When in 1510 Dominican friars led by Pedro de Córdoba arrived in Santo Domingo, they were horrified at the Spaniards’ treatment of the Indians, the massacres, the brutality of slavery, and the intense exploitation of the natives and they denounced it. Las Casas rejected the Dominicans’ criticism and defended the encomienda system by which Spaniards distributed laborers to the conquerors. In 1513, Las Casas joined the expeditions of Diego Velázquez de Cuéllar and Pánfilo de Narváez to conquer Cuba, acting as chaplain. He witnessed horrifying murders and torturers of the indigenous people. Once again, he received a reward, this time of gold and slaves. For a year he lived as both colonist and priest.

Then in 1514, while studying the Book of Ecclesiasticus or Sirach (which is part of the Catholic Bible but not part of either the Jewish or Protestant Bibles) he came across a passage that called his beliefs into question. It read:

If one sacrifices from what has been wrongfully obtained, the offering is blemished; the gifts of the lawless are not acceptable. … Like one who kills a son before his father’s eyes is the man who offers sacrifice from the property of the poor. The bread of the needy is the life of the poor; whoever deprives them of it is a man of blood.[7]

Reading this passage—and no doubt meditating on the horrors that he had both participated in and witnessed—Las Casas suddenly decided to break with his past. He gave up his haciendas, his encomienda, his slaves. He began to encourage others Spaniards to do the same, but of course they refused and they resented him.

Las Casas then traveled to Spain to take his case to King Ferdinand, and he succeeded in having one meeting with him, but then the monarch died in 1516. Many of the other higher-ups in the Spanish state and Church, such the Bishop of Burgos, Juan Rodríguez de Fonseca, who controlled the Crown’s business in the Americas, were themselves encomenderos who profited from the labor of the indigenous and they rejected Las Casas’ appeals to protect the Indians. Fearing that the entire population of the Indies, the Caribbean islands, might be annihilated, Las Casas wrote his Memorial de Remedios para las Indias (Memorandum on Remedies for the Indies) to be presented to the regents who now rules, calling for a moratorium on all Indian labor to protect the indigenous people and allow the recuperation of their populations.

At the time, no one understood the etiology of the diseases that were carrying off the majority of the indigenous people; the germ theory of disease and the causes of contagious pandemics, such as small pox, were unknown. Las Casas could see that Indians were dying more rapidly than Africans, though he did not know that was because the Africans had greater immunity to the diseases being carried by the European conquerors. So Las Casas initially proposed that Indians encomienda laborers be replaced by African slaves who seemed more hardy. Las Casas soon came to regret this position when he saw that the Spanish treated the Africans as badly as they had the indigenous people and he became an advocate for both Indians and Africans in the Americas.

Convinced by Las Casas’ argument that the Indians needed to be protected, one of the regents, Cardinal Ximenes Cisneros, put the Carmelite monks in charge of the Indies. Las Cases himself was given the official title and position of “Protector of the Indians.” When the Carmelites arrived in the Indies and faced the hostility of the Spanish encomenderos, they declined to implement Las Casas’ reforms. Las Casas for his own protection had to take refuge in a Dominican monastery.

Theodore de Bry’s illustrations to Las Casas’ Brief Account of the Conquest of the Indies.

During the next fifty years, as the Spanish came to rule all of Mexico, Central America, and the greater part of South Americas, subjecting the indigenous to the same sorts of horrors as those they had carried out in the Caribbean, Las Casas continued to indict the Spanish conquerors and colonists. His A Brief Account of the Destruction of the Indies, written in 1542 but not published until 1552, he described the horrors of the Spaniards’ massacres and enslavement of the indigenous peoples. The book was translated into various languages and published with horrifying illustrations in many editions by Protestants who wanted to demonstrate the evils of the Catholic Church, what is called “the black legend.”

Under pressure from Las Casas, in 1542 King Charles V promulgated the New Laws to protect the Indians from exploitation. While this was a victory for Las Casas, there was initially great resistance and it took a long time before the Spanish colonists began to comply, and even then, the Indians remained subject peoples. Unable to live in the colonies because of the threats on his life, Las Casas was forced to return to Spain where he continued to fight to protect the indigenous people though his writing and his many appeals to the authorities. We turn now to the famous Valladolid debates on the people of the Indies.

The Valladolid Debate and the Right of Nations to Self-Determination

Theologian Juan Ginés de Sepúlveda.

King Carlos V, concerned about conditions in the Spanish American colonies decided to organize a debate between the two principal intellectuals on opposite sides of the question. Juan Ginés de Sepúlveda, speaking for one full day, laid out his argument. He claimed that the indigenous people of the Americas were barbarians: ignorant, unlettered, and unreasoning, incapable of learning anything except the simplest tasks. The Spaniards, he argued, being superior in intelligence and morality, had he right to make war on them and conquer them. They Indians were, he said, incapable of governing themselves. He argued that they were sunk in depravity, worshipping idols and engaging in human sacrifice. He quoted the Bible and other authorities to argue that in ancient times such people had been justly exterminated or enslaved. Natural law, he averred, dictated that the Spaniards, superior in intelligence and morality, should govern them.

In response, Las Casas spoke for five days, reading the entire 253 folio pages, over 60 chapters, today making up 350 printed book pages. Las Casas either refuted Sepúlveda’s arguments, such as the claim that the indigenous Americans were ignorant and incapable of governing themselves, by providing evidence of their intelligence and self-government, or he argued, as in the case of idolatry and human sacrifice, that these practices had to be seen as demonstrating their religious inclination, their attempts to worship God. Las Casas denied the Spaniards’ right to ever invade, occupy, conquer, and subject the indigenous. He argued that the Spaniards’ wars against the Indians were unjust and therefore enslavement of the Indians was illegal and wrong, since only the captives of a just war could be enslaved. The Spaniards claimed to be superior, more civilized, but Las Casas wrote, “… in the absolutely inhuman things they have done to those nations, [the Spaniards] have surpassed all other barbarians.”[8]

Las Casas argues In Defense of the Indians, the text of his argument in the Valladolid debate, that the Indians have governments with kings, dignitaries, and laws. To get a sense both of the foundation of Las Casas’ arguments and the contempt in which he holds Sepúlveda it is worth quoting one passage in full:

Now if we shall have shown that among our Indians of the western and southern shores (granting that we call them barbarians and that they are barbarians) there are important kingdoms, large numbers of people who live settled lives in a society, great cities, kings, judges, laws, persons who engage in commerce, buying, selling, lending, and the other contracts of the law of nations, will it not stand proved that the Reverend Doctor Sepúlveda has spoken wrongly and viciously against peoples like these, either out of malice or ignorance of Aristotle’s teaching, and therefore, has falsely and perhaps irreparably slandered them before the entire world? From the fact that the Indians are barbarians it does not necessarily follow that they are incapable of government and have to be ruled by others, except to be taught about the Catholic faith and to be admitted to the sacraments. They are not ignorant, inhuman, or bestial. Rather, long before they heard the word Spaniard they had properly organized states, wisely ordered by excellent laws, religion and custom.[9]

Las Casas asks Sepúlveda to remember that when Rome tried to conquer Spain the Spaniards were considered barbarians, and he asks, “did you [Spaniards] also have the right to defend your freedom and indeed your very life by war?”

Las Casas makes his point on the right of nations to self-determination most strongly in this passage:

Since, therefore, every nation by the eternal law has a ruler or prince, it is wrong for one nation to attack another under pretext of being superior in wisdom or to overthrow other kingdoms. For it acts contrary to the eternal law, as we read in Proverbs: ‘Do not displace the ancient landmark [i.e., borders], set up by your ancestors.” [Proverbs 22, 28.] This is not an act of wisdom, but of great injustice and a lying excuse for plundering others. Hence every nation, no matter how barbaric, has the right to defend itself against a more civilized one that wants to conquer it and take away its freedom. And, moreover, it can lawfully punish with death the more civilized as a savage and cruel aggressor against the law of nature. And this war is certainly more just than the other one, that, under pretext of wisdom, is waged against them.[10]

Las Casas also argues that the Spanish have no right to impose Christianity by force. These statements are remarkable because clearly Las Casas is justifying, defending, and allying himself with the Indians who resist, rebel, and wage war against the Spaniards.

He concludes the chapter dealing with these questions with this.

On the other hand, no free person, and much less a free people, is bound to submit to anyone, whether a king or nation, no matter how much better the latter may be and no matter how advantageous he may think it will be to himself…. No free nation, therefore, can be compelled to submit itself to a wiser one, even if such submission could lead to [its] greater advantage.[11]

We have, of course, many fundamental disagreements with Las Casas. He lived and wrote more than two hundred years before the Enlightenment and the French Revolution and more than three hundred years before the Russian Revolution. He had no modern ideas of equality, justice, or democracy, living as he did in an age when in Europe the Christian religion formed the fundamental ground for all accepted thought. While he was sympathetic to the indigenous pagans who had never known Christianity, he believed that the Muslim infidels who knew but had rejected Christianity had to be opposed. Las Casas was not among those radical Christians like his contemporary, the German theologian Thomas Müntzer (1489-1525), who opposed both the Catholic Church and Martin Luther the leader of the Protestant Reformation, as well as the German nobility, a man who led a peasant revolution advocating a kind of Christian Communism.

Still, Las Casas completely rejected the idea that the Spaniards were superior to the Indians, arguing that all human beings are intelligent and capable of self-rule. In fact, he said that the Spaniards were the most barbarous because of the terrible and inhumane way they treated Indians. He argued that, as Jesus said, the Spaniards should love their neighbors, even if their neighbors were barbarians[12]. Though Las Casas believed that far from being barbarians the Indians were superior to the Spaniards.Las Casas accepted the existence of the Spanish monarchy and nobility and the Catholic hierarchy, and accepted patriarchy. He wanted to reform the Spanish state and its empire, reform them fundamentally, but not destroy them. Nevertheless, this Spanish reformer simply on the basis of the fundamental Christian principle that “all mankind is one”—created by one God and all capable of salvation—proved able to develop not only a defense of the Indians but a theory of national self-determination that one could apply to other nations as well.

Las Casas’ Theory of the Right to Self-Determination Applied to Ukraine

There are many interesting and disturbing parallels between Spanish imperialism five hundred years ago and Russian imperialism today. Both Spain and Russia both claimed to be states chosen by God to lead the way to a more moral world under their rule. Ferdinand and Isabella, who expelled the Jews and Muslims from Spain, financed Columbus’ voyage to the East Indies, in which he stumbled on the Americas, the initiators of the conquest of the New World, were known as the Catholic Monarchs, the Defenders of the Faith. Similarly Vladimir Putin, backed by Patriarch Kirill of the Russian Orthodox Church, argues for the superior morality of Russia in its war against Ukraine. Putin also argues that the Ukrainians are Nazis, that is barbarians, and must therefore be conquered and subjugated. Spain and Russia were both prepared to destroy others’ civilizations and kills thousands to create colonies, or in Russia’s case recreate a Ukrainian colony, and to enslave a population.

Today, however, as one witnesses the Russian war on Ukraine, with its widespread destruction of homes schools, and hospitals, of fields and factories, and its war crimes, including torture and murder of civilian men, women, and children, it is clear that, like the Spanish, the Russian president and his coterie are the real barbarians. Today we write in defense of the Ukrainians as he once did in defense of the Indians, as allies who support their right to arm and to defend themselves and their nation and to preserve their sovereignty.

As Las Casas says, “No free person, and much less a free people, is bound to submit to anyone, whether a king or nation, no matter how much better the latter may be and no matter how advantageous he may think it will be to himself.” Lenin–for different reasons and with distinct goals–would have agreed.

Notes

[1] Vladimir Lenin, The Right of Nations to Self-Determination, “Conclusion.”

[2] Perry Anderson, “American Foreign Policy and Its Thinkers” Special Issue of New Left Review, Sept./Oct., 1983 (#83), p. 10.

[3] Woodrow Wilson, “Fourteen Points.”

[4] Anderson, “American Foreign,” p. 10.

[5] The United States still had colonies: Philippines, Puerto Rico, and a kind of protectorate over Cuba, and some other smaller ones, but it was not acquiring more, preferring to us diplomacy, economic power, and when necessary, military intervention in foreign states on one pretext or another. It occupied Haiti and Nicaragua for many years, but it did not take formal political control of them.

[6] Prof. Lewis Hanke made the study of Las Casas the focal point of his research and writing for decades. His books that deal with Las Cases include: The Spanish Struggle for Justice in the Conquest of America (1949); Aristotle and the American Indians: A Study in Race Prejudice in the Modern World (1959); All Mankind Is One: A Study of the Disputation Between Bartolome De Las Casas and Juan Ginés De Sepúlveda in 1550 on the Religious and Intellectual Capacity of the American Indians (1974). Many other Latin Americanists have of course also written on Las Casas and he has been the subject of fiction and film as well. José Luis Olaizola, a Spanish writer of historical fiction, published Bartolomé de Las Casas, crónica de un sueño in 1991 (Planeta). Jean-Claude Carrière’s Jean-Claude Carrière, La Controverse de Valladolid (Paris: Le Pré aux Clercs, 1992), which was also made into a film for with the same title by director Jean-Daniel Verhaeghe and available for free on Vimeo at: https://vimeo.com/512013420 . There is also an Austrian Film, “Bartolome de las Casas” (1992), and Mexican film “Fray Bartolome de las Casas,” (1993) as well as the Catholic Pivoltal Players film in 2020.

[7] Brading, David (1997). “Prophet and apostle: Bartolomé de las Casas and the spiritual conquest of America,” Cummins, J. S. (ed.). Christianity and Missions, 1450–1800. An Expanding World: The European Impact on World History, 1450–1800 (Aldershot: Ashgate, 1997), 117-138.

[8] Bartolomé de Las Casas, In Defense of the Indians, translated and edited by Stafford Poole, C.M., foreword by Martin E. Marty (DeKalb: Northern Illinois University, 1999), p. 29

[9] Las Casas, In Defense, p. 42.

[10] Las Casas, In Defense, p. 47.

[11] Las Casas, In Defense, p. 48.

[12] Las Casas, In Defense, p. 39.

Leave a Reply