By: Norman G. Finkelstein

OR Books, 2014. 83 pp. + notes, paperback, $10

By: Norman G. Finkelstein

OR Books, 2012. 454 pp. + notes and index, paperback, $20

Norman Finkelstein has made his career taking the nasty assignments. It’s been dirty work, but presumably someone had to do it: plowing through the works of Joan Peters, Daniel Goldhagen, Elie Wiesel, Alan Dershowitz, and a small army of official and unofficial Israeli state propagandists. The result has been a series of enormously valuable analytical and polemical works including Image and Reality of the Israel-Palestine Conflict (Verso, 1995); A Nation on Trial: The Goldhagen Thesis and Historical Truth (co-authored with Ruth Bettina Birn, Henry Holt and Co., 1998); The Holocaust Industry: Reflections on the Exploitation of Jewish Suffering (Verso, 2000); and Beyond Chutzpah: On the Misuse of Anti-Semitism and the Abuse of History (University of California Press, 2005. 2nd updated edition, June 2008, with an appendix written by Frank J. Menetrez, “Dershowitz vs Finkelstein. Who’s Right and Who’s Wrong?”).

The last work included a dissection of Alan Dershowitz’s The Case for Israel, with Finkelstein explosively showing how much of the book closely resembled, without attribution, Joan Peters’ From Time Immemorial (1984). The latter purported to be a study showing that the Arab population in Palestine was built on immigration induced by the economic benefits of Zionist settlement, which Finkelstein himself had shown two decades earlier to be a monstrous fake.

Dershowitz, the supposed civil liberties lawyer (who endorses torture and collective punishment by Israel and the United States in the “war on terror”), attempted to suppress the University of California’s publication of Beyond Chutzpah, and subsequently launched a vendetta that resulted—“allegedly,” inasmuch as Dershowitz and DePaul University denied it—in Finkelstein’s dismissal from his teaching position at that institution, whose administration cited as its official grounds Finkelstein’s supposed “non-Vincentian” style.

Exiled from academia with an unspecified settlement from DePaul, Finkelstein turned to independent scholarship and political writing, mostly published by OR Books (New York). Titles include This Time We Went Too Far: Truth and Consequences of the Gaza Invasion (2010); Goldstone Recants. Richard Goldstone renews Israel’s license to kill (2011); What Gandhi Says About Nonviolence, Resistance and Courage (2012); and the two recent books on which I concentrate here.

Old Wine, Broken Bottle is a brief book, a trenchant essay-review of the celebrated liberal Israeli journalist Ari Shavit’s My Promised Land, highly acclaimed for its supposed boldness in facing up to some unpleasant facts of ethnic cleansing in the formation of the State of Israel. Quite the contrary, says Finkelstein; Shavit largely repeats the facts documented by Israeli “new historians,” notably Benny Morris (on whom more below), while putting his own shiny gloss on the Zionist pioneers in order “to justify Israel’s creation at the expense of the indigenous population” (21).

“I am no judge, I am an observer,” Shavit declares, but alas, he observes through the judgmental lens of an unreconstructed European imperialist. … In Shavit’s distillation, even the sheep of these [indigenous peasant] Palestinians are “gaunt.” Meantime, the Zionist pioneers manage, while making the desert bloom, also to peruse Marx, Dostoyevsky and Kropotkin, revel in Beethoven, Bach, and Mendelssohn, and are even green-friendly, as they adopt a ‘humane and environmentally friendly socialism’ (he doesn’t say whether they recycle paper and soda bottles) (22, 24).

The above paragraph is typical of Finkelstein’s style, and there’s plenty more where that came from. He is particularly scathing when it comes to Shavit’s lavish celebrations of Tel Aviv’s steamy night life, his praise of Operation Cast Lead (Israel’s 2008-09 invasion of Gaza, predecessor of the recent carnage), and the self-promoting way Shavit has positioned himself as a reformed critical leftist, in a manner calculated to sustain his own prestige:

In his youth he was a “peacenik,” who opposed settlements, supported a Palestinian state, and championed human rights. … It’s not so much that he has inched, let alone lurched, across the Israeli political spectrum, but rather that the whole Israeli spectrum has shifted to the right, and he has, conveniently, moved right along with it. His personal odyssey (which parallels that of Israeli historian Benny Morris) is thus exemplary of the morphing Israel itself has undergone in recent years, one that has estranged it from the moral universe of American Jews (71, emphasis added).

That last phrase is key to Finkelstein’s bold hypothesis laid out in Knowing Too Much, which I’ll scrutinize in more detail. Interestingly, Old Wine, Broken Bottle received fleeting attention in a recent New York Review of Books piece by Jonathan Freedland—not for its substance, unfortunately, but only with a muddled quotation of Finkelstein’s rendering of a Yiddish joke. (Enjoy the joke for yourself on pages 82 and 97, fn 2.)

If the demolition of Shavit is a quick and breezy read, Knowing Too Much: Why the American Jewish Romance with Israel Is Coming to an End is a challenging text, which Finkelstein has described as his most important book. Although published in 2012 and mostly written several years earlier, the book deserves attention now in the wake of the recent Gaza massacre, which offers a striking opportunity to test its central tenet.

“Recent surveys strongly suggest that American Jews are ‘distancing’ themselves from Israel,” Finkelstein begins. For supporters of Palestine to turn this development to political account, he argues,

it must be shown to American Jews that the choice between Israel’s survival and Palestinian rights is a false one; that it is in fact Israel’s denial of Palestinian rights and reflexive resort to criminal violence that are pushing it toward destruction. …

It must be shown that what is being asked of them is not more but also not less than that they be consistent in word and deed when it comes to the people of Palestine. If it can be demonstrated that the enlightened values of truth and justice are on the side of Israel’s critics, then it should be possible—the evidence is already there—to strike a resonant chord among American Jews that goads them into action (xiii, xix).

The book then proceeds with a full-length demonstration that indeed, “truth and justice are on the side of Israel’s critics,” that these values are indeed incompatible with Israel’s behavior and with the deteriorating state of Israeli society, that American Jews remain broadly committed in their majority to enlightened values, and that they (and others) will no longer swallow a narrative of the Middle East that amounts to “Exodus with footnotes.” (Note for readers too young to remember: “Exodus” here refers not to the Biblical text but to the 1958 Leon Uris novel, one of the most racist works of all time—most worthless as literature and most spectacularly successful as political propaganda—and to the blockbuster movie it spawned.)

Before surveying the somewhat contradictory evidence for Finkelstein’s optimistic hypothesis, it is worth briefly summarizing the wide ground he covers. It repays close reading. As in some earlier works, he points out that the full-contact American Jewish “romance with Israel” really flowered not in the early days of the Israeli state, but after its smashing victory over Arab armies in 1967, when “Israel came to incarnate for American Jewish intellectuals the high cause of Truth, Justice and the American Way, to which they could now assert a unique connection by virtue of blood lineage. … The most zealous of these newly minted supporters of Israel were the Jewish liberals who metamorphosed into right-wing neoconservatives” (41).

Finkelstein goes on to a detailed critical dissection of the thesis of professors John Mearsheimer and Stephen Walt, in The Israel Lobby and U.S. Foreign Policy, “that the lobby has so skewed Washington’s foreign policy that, acting on Israel’s behalf, it even caused the George W. Bush administration to attack Iraq in 2003 although the war did not serve American interests” (45).

It’s an important discussion, in that sizeable chunks of the pro-Palestinian movement have fixated on the diversionary notion that Israel, or Zionists, or Jews, are the driving force behind U.S. regional or even global policies—as if imperialism didn’t exist.

Finkelstein concludes this section with a sharply drawn contrast: “Israeli Jews most resemble white evangelical Protestants and Mormons in their mutual preference for a militaristic foreign policy. … The gap in mindset between American Jewry and Israelis on war and peace and kindred issues verges on an abyss” (89). Setting aside this somewhat stereotypical rendering of Mormons and white evangelicals, I’ll suggest below that the most important “abyss” may exist not between Israeli and American Jews, but within the latter community.

In the book’s central chapters, Finkelstein proceeds with a close reading of Israel’s human rights record and a critical assessment of how the discussion around these matters has evolved. Regarding the torture of prisoners during the first Palestinian intifada, he contrasts Jeffrey Goldberg’s account (in Prisoners: A Muslim and a Jew across the Middle East Divide, which Finkelstein calls “a sophisticated work of ideology” that “registers the limits of what is currently permissible to acknowledge in popular literature on the Israel-Palestine conflict”) with the brutally detailed reporting of Ari Shavit in his long-ago early days (102, 104-5).

He indicts the reporting of Human Rights Watch on the Israel-Hezbollah war in 2006 for what he calls “human rights revisionism” in HRW’s conclusion to its report Why They Died. The conclusion flew in the face of HRW’s own investigative findings, stating “that ‘strong evidence’ existed that Hezbollah committed war crimes, whereas it found no evidence that Israel deliberately targeted civilians and reserved judgment on whether Israel committed war crimes” (136).

He juxtaposes the ravings of Alan Dershowitz on Israel’s wars with the informed scholarship of Israel historian Zeev Maoz, and Michael Oren’s propagandist account of Israel’s defensive 1967 war with the work of Maoz and with what U.S. military and intelligence experts knew at the time about Israel’s full confidence in its military superiority and its aggressive intentions.

Finkelstein sums up his premise “that current academic scholarship on the Israel-Palestine conflict has achieved impressive levels of objectivity, that this historical record is better known, and that consequently more and more people are able to see through the propaganda from which Israel has benefited for so long. The battle, however, is far from over” (183). Obviously, the entire book is an intentional, and important, intervention in that long battle.

A vital chapter details the evolution of Benny Morris, from a pioneering “new Israeli historian” whose scrupulous archival research revealed the facts of Israeli ethnic cleansing and expulsion of Palestinians during and after the 1948 war, to an apologist and advocate of those very acts. Morris never resorted to nakba denial but instead came to argue that expulsion was essential to Israel’s existence and should have been, if anything, carried out more fully. (Or as Ari Shavit puts it in recounting the destruction of the village of Lydda, “If Zionism was to be, Lydda could not be.”)

To explain “the roots of Morris’s bizarre transformation from a relatively judicious liberal historian into a ranting right-wing crackpot,” Finkelstein suggests,

It seems Morris now aspires to become Israel’s court historian. … It is also true that the political left, and the tiny space Morris carved out in its vicinity, barely exists any longer in Israeli life [and that] to become a court historian he had to forsake both his professional calling and political sensibility. …

Still, it has not been so much his personal liabilities as the liabilities of Israeli society that have nudged Morris ever more rightward. To become Israel’s court historian he had to keep pace ideologically with it. … If Morris has gone berserk, it is because he aspires to be the official storyteller of a nation that itself has gone over the cliff (294, 295-6, 297, emphasis added).

It remains to assess Finkelstein’s optimistic contention that American Jews, with their traditional attachment to liberal politics and social justice principles, are moving away from the Israeli embrace, with potentially a long-term impact on politics.

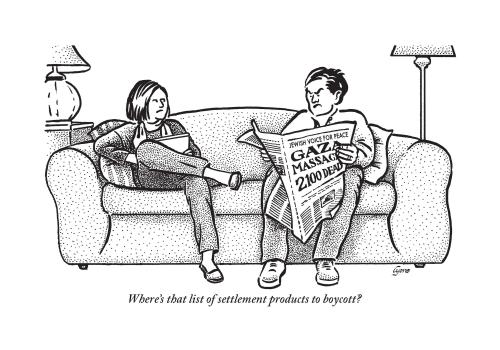

There is certainly positive evidence. The growth of the organization Jewish Voice for Peace (JVP, www.jewishvoiceforpeace.org) is a striking example, as are the growing numbers of Jewish activists in campus Students for Justice in Palestine chapters, BDS (boycott/divestment/sanctions) campaigns, and similar efforts. Jewish as well as other academics have rallied in outrage to the defense of Professor Steven Salaita, whose promise of a tenured position at the University of Illinois was peremptorily cancelled after the school came under donor pressure over his angry twitter posts on the Gaza massacre (www.change.org/p/phyllis-m-wise-we-demand-corrective-action-on-the-scandalous-firing-of-palestinian-american-professor-dr-steven-salaita).

A similar effort has sprung up in defense of San Francisco State University Professor Rabab Abdulhadi, who is under attack by the tiny but heavily funded rightwing Zionist “AMCHA Initiative” (see www.solidarity-us.org/site/?p=4220).

Earlier this year, at the General Assembly of the Presbyterian Church of North America held in Detroit, Jewish activists partnered with the Israel Palestine Mission Network of the church, as well as Friends of Sabeel North America and young Palestinians, in a closely contested and ultimately successful initiative for divestment of church funds from Caterpillar, Hewlett-Packard, and Motorola Solutions, three U.S. corporations engaged in some of the dirtiest and most murderous profiteering from the Israeli occupation.

In October as this review is written, Jewish students have organized a large “Open Hillel” conference at Harvard University, with the purpose to “create a space for open conversation on Israel/Palestine and other issues of importance to the Jewish community, without external restrictions. Because Hillel International limits the kind of conversations we can have, we decided to show the limitless potential of a conversation not bogged down by ‘standards of partnership’ and the political whims of big donors” (www.openhillel.org/conference.php).

This initiative was a response to the official partnering of the Hillel organization with AIPAC and its policy of barring Hillel campus chapters from participating in events where any co-sponsoring organizations are supporters of BDS. (Proud disclosure: this reviewer’s daughter was one of the conference organizers.) Drawing over 300 mostly young participants and a diverse array of speakers and viewpoints, the event received substantial and generally favorable comment in the October 13 Jewish Daily Forward, an organ that would more likely have ignored or trashed it in earlier times.

The Hillel exclusion policy seems reminiscent of the Catholic Church’s pronouncement of papal infallibility—not in medieval times when Church authority was powerful, but in the nineteenth century when it was already eroding (or more recently when the Soviet Union proclaimed “the leading role of the Communist Party,” not under Stalin when no one dared to question it, but in 1964 when its credibility was visibly fraying). It has produced a significant backlash, with at least one Hillel chapter, at Swarthmore, openly declaring its noncompliance.

All this is to the good, but hardly the full story. For one thing, American Jewish support of enlightened values may not be all that it once was. Besides those Jewish neocon militarists, there’s the concentrated influence of the ultra-Orthodox in certain localities. The well-publicized scandal of the Hasidic sect that took control of and utterly gutted the East Ramapo Central School District in Rockland County, New York—as viciously as any fundamentalist Christians could have done—is a frightening example.

As well, official U.S. political culture remains unaffected as yet by signs of Jewish disaffection from Israel. At the height of the most recent Gaza massacre, we saw the United States Senate voting unanimously in support of Israel’s maximum (and unattainable) war aims, including the dismantling of Hamas and the breaking of the barely formed Palestinian unity government.

That loyalty oath to Israel was passed by “unanimous consent,” with 79 cosponsors. (The socialist Bernie Sanders and the liberals’ newest icon Elizabeth Warren were not among the 79, but they raised no objection to the resolution—to the dismay of many of their supporters.) This despite the fact that President Obama’s global credibility in the overall Middle East meltdown can’t exactly be enhanced by the spectacle of Benjamin Netanyahu kicking him in the face, over and over again.

There are also serious shortcomings, to put it mildly, in the organizational expression of liberal Jewish uneasiness over Israel’s insubordination to Washington’s pleas for restraint. Take J Street (please). This is the organization created to form a “pro-Israel, pro-peace” counterweight to the power of AIPAC (American Israel Public Affairs Committee), which operates in essence as the political lobby of the right wing of Likud. Despite (or because of) that vapid and essentially meaningless slogan, J Street has attracted significant support from American Jews unsettled by Israel’s increasingly embarrassing rampages.

The problem is that J Street is firmly committed to a policy of doing nothing beyond issuing statements, and opposing those who actually do anything. While opposed on paper to Israeli settlement expansion, it not only opposes BDS but refuses to endorse even boycotts of settlement products. (Another organization, Partners for Progressive Israel formerly known as Meretz USA, to its credit does support the settlement-products boycott.) One of J Street’s representatives turned up at the Presbyterian Assembly to oppose the church divestment initiative. Proclaiming itself “pro-peace,” it supported the Israeli “Protective Edge” slaughter in Gaza. J Street’s theme song should be “Everyone Knows this is Nowhere,” and its slogan “Don’t just do something, stand there!”

The stark contrast between J Street’s stated anti-occupation principles and its do-nothing practice suggests that the “abyss” that Norman Finkelstein hopefully cites may be opening, but slowly. It seems that J Street tries to occupy a meaningless middle ground in a polarized debate that’s opening up within the U.S. Jewish population (I hesitate to say “community”) at least as much as an “abyss” between Israeli and American Jews. A sign of real progress would be an exodus from J Street of those, especially young Jewish activists, who want to act on their principles and who really belong in Jewish Voice for Peace, or the U.S. Campaign to End the Israeli Occupation, or similar efforts.

Although beyond the scope of this review, it’s worth mentioning that Finkelstein has become controversial within some sectors of the Palestine solidarity movement for critical comments he’s made regarding the BDS campaign. (In fact, he supports BDS while dismissing some rather extreme illusions within the movement that BDS is capable of liberating Palestine.) At the same time, he’s been highly pessimistic—somewhat overly so, in my view—about the degree to which Mahmoud Abbas will completely capitulate to U.S. and Israeli demands for unconditional surrender of Palestinian demands.

Leaving those issues aside for another discussion, Knowing Too Much is essential reading for understanding Finkelstein’s real views, why the debate in the U.S. Jewish population exists, and the critical importance of deepening it.

Leave a Reply