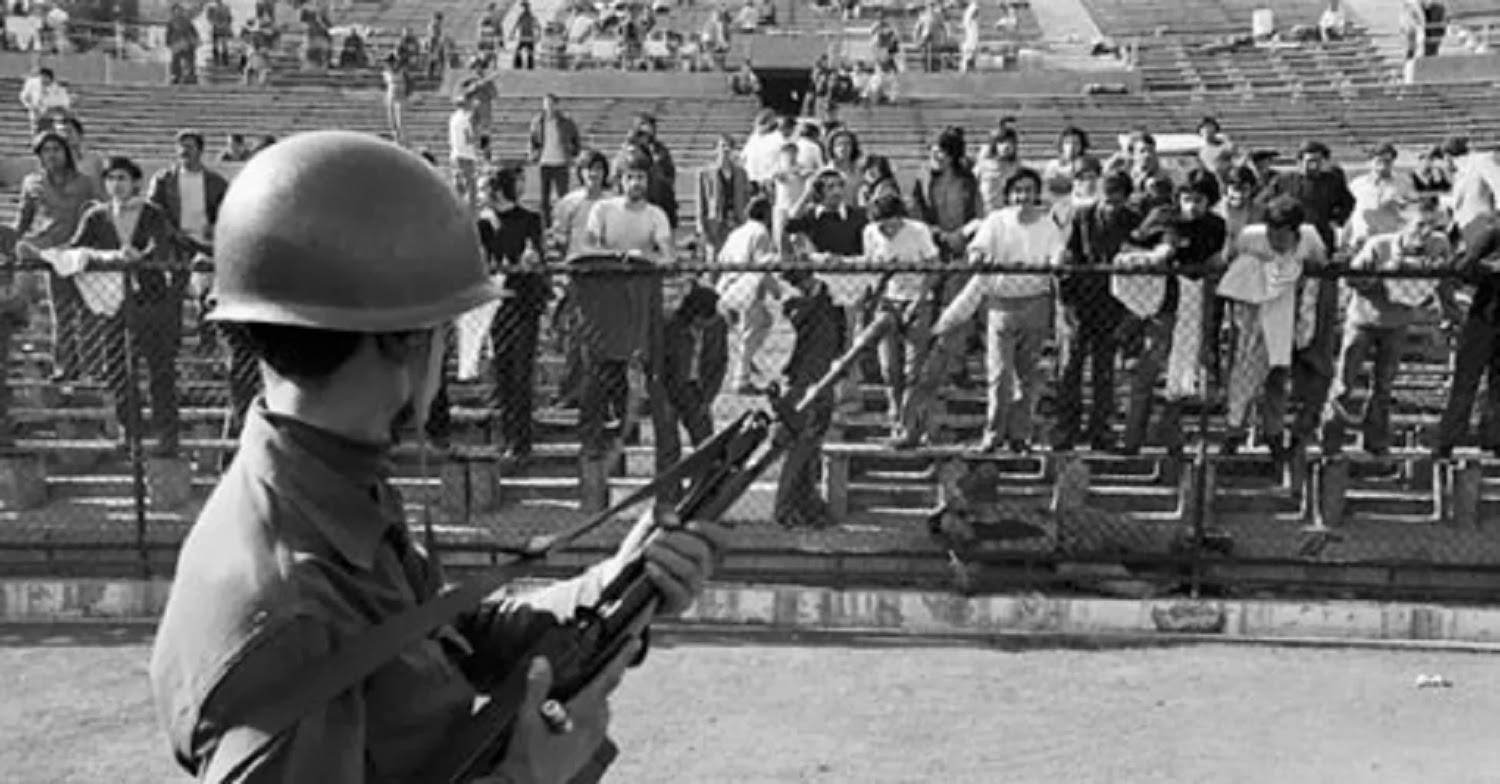

Students protest the government takeover of the University of Central America by the Nicaraguan government.

August 21, 2023 -The cry of alarm of academics, teachers and university workers (including CETRI – Tricontinental Center*) in the face of the new escalation of the offensive of the Ortega-Murillo regime against Nicaraguan universities. First signatories below.

As academics, teachers and university workers, we would like to make public our deep concern at the alarming news reaching us from Nicaragua that shows a new escalation of the offensive that the Ortega-Murillo regime has launched against Nicaraguan universities.

Since the end of 2020, taking advantage of reforms to the General Law on Education and the Law on the Autonomy of Higher Education Institutions, more than 26 universities have been closed and their property confiscated. Together with the assets of some of these universities, new public universities were created without following the procedures established for this purpose, which aggravated the situation of confusion and anxiety for students that already existed in the country’s higher education subsystem. This time, a new threshold has been crossed in the actions carried out for years to threaten, weaken, isolate and finally close one of the most important universities in the country, the Universidad Centroamericana (UCA).

As reported by the Central American Province of the Society of Jesus in a statement dated August 16, 2023, “the serious accusations brought against the UCA in the official notice issued by the Tenth Criminal Court of the District of Managua on August 15, 2023, in which it is described as a ‘center of terrorism’ and accused of having ‘betrayed the trust of the Nicaraguan people’ and of having ‘transgressed the constitutional order, the legal order and the order governing the country’s institutions of higher education” are absurd and deceptive. We share this view all the more because no fair and independent judicial body has presented evidence to support these accusations.

On the basis of these accusations, the order was given to freeze bank accounts, expropriate property and the de facto takeover by the National Council of Universities (CNU), which has become the state organ of repression and submission of universities to absolute political control. Not content with disrespectfully and irresponsibly endorsing the extinction of the UCA, the CNU rushed to appoint new authorities to run the university without the support or agreement of the UCA academic community.

In its 63 years of existence, UCA has become one of Nicaragua’s leading and even the leading university and is considered a model of the kind of university that should be established in poor countries with poor education systems, weak democracies and development models based on extractivism and the supply of cheap labour. UCA has demonstrated that it is possible to provide quality higher education to all sectors of the population and to contribute to the creation of a truly humane and sustainable development model.

Since its foundation in 1960, UCA has contributed to the development of science and research at national and international level, offering young people and professionals a comprehensive academic training with criteria of excellence and based on humanistic values. This vision led this institution to become a space for open debate and promotion of social and political rights during the years of the Somoza dictatorship.

During the 1980s, the UCA preserved its founding principles and maintained a relationship of respect with the new authorities, while some of the decisions taken by the higher education governing bodies of the time had undermined the structure and functioning of the UCA.

Since its inception, the UCA has been the headquarters and actively supported the work of the Nicaraguan Academy of Sciences, which never received state support and was eventually closed along with thousands of other civil non-profit organizations.

Through its research and social intervention centres and institutes, UCA has invested in areas such as education, sustainable development, regional history, science and has provided social services such as legal advice and psychological support, both to the educational community and to society at large.

It also played an important role in the processes of dialogue, promotion of peace and recognition of multiculturalism after the armed conflict of the 1980s. Its rector had been invited, with the agreement of Daniel Ortega’s government, to participate in the search for a peaceful solution to the serious socio-political crisis that erupted in April 2018.

In 2010, the World University Ranking, published annually by the Spanish National Research Council, ranked the Central American University of Nicaragua first among the 52 institutions and centers of higher education operating in Nicaragua. It is also among the top ten on the long list of universities in Central America.

In 2012, UCA achieved another important academic recognition when it was included by the Quacquarelli Symonds (QS) ranking in the list of 250 institutions considered the most prestigious centers of higher education in the Latin American region, where more than 7,000 higher education institutions operate, of which nearly 2,000 are universities. UCA is the only Nicaraguan university to be included in this list. Throughout its history, UCA has been an internationally recognized space for knowledge production, connected to different international networks that connect academic centers in Latin America, North America, Europe and Asia.

All of the above highlights the intentions of the Ortega-Murillo regime to close all spaces that encourage critical thinking, the free exchange of ideas and informed debate on issues of concern to the country. Ortega’s plan to establish a dynastic dictatorship in Nicaragua, equal to or worse than those that plunged Latin American countries into pain and doldrums for many decades, is no longer in doubt. Free and autonomous universities have no place in this project and that is why they want to destroy the UCA.

As academics, Nicaraguans or from other countries, we, who have had the privilege of knowing and working with colleagues of the UCA or who know its trajectory, because it has been an example for those who want to build free educational institutions committed to the future of our countries, we want to make our protest heard against what is currently happening in Nicaragua and we call on university organizations, rectors’ conferences, professors and students from all over the world, men and women who love justice, peace and freedom, to condemn the Ortega-Murillo regime for its senseless attacks on Nicaraguan universities.

We support and take up the requests of the Central American Province of the Society of Jesus addressed to the Ortega-Murillo regime:

that the severe, abrupt and unjust measure adopted by “justice” be immediately annulled and corrected;2. an end to the growing government aggression against the University and its members;3. that a rational solution be sought in which truth, justice, dialogue and the defence of academic freedom prevail.

Given the arrogant and disrespectful manner in which the CNU-appointed authorities presented themselves on the UCA campus, we demand respect for the physical integrity and freedom of all UCA staff. We demand respect for the job stability of all academic and administrative staff and the prompt delivery of academic records to all students who request them.

We call on the international academic community to be attentive to the events in Nicaragua, to raise their voices in protest and to express their solidarity with the UCA through concrete actions.

Today, more than ever, the motto with which Dr. Mariano Fiallos Gil, “father of university autonomy” in Nicaragua, undertook the struggle for the autonomy of universities and for their transformation into institutions committed to the nation that welcomes and supports them must be heard:

“FOR THE FREEDOM OF THE UNIVERSITY”.

University centres, groups and collectives

Institute of Regional Studies of the University of Antioquia (Colombia)

Institute of Social and Human Sciences of the Rafael Landívar University (Guatemala)

Institute for Development Policy, University of Antwerp, Belgium

Institut de Hautes Études de l’Amérique latine (IHEAL), Université Sorbonne Nouvelle

Working Group of the Latin American Social Science Council (CLACSO) “Gender, (in)equality and rights in tension”

CLACSO Working Group “Borders, Regionalisation and Globalisation”

CLACSO Working Group “Political Ecology(s) from the South / Abya-Yala

University of the Land of Puebla (Mexico)

Utopía Collective, Puebla (Mexico)

Geobrujas – Community of Gerographers, Mexico City (Mexico)

Latin American Institute for the Study of Peace and Citizen Coexistence (ILEPAZ), Mexico City, Mexico

Initiatives of Bridges for Students of Nicaragua (IPEN), Costa Rica

Flora Tristan Centre for the Study and Promotion of Gender Equality, National University of Misiones (Argentina)

Alba Sud, Barcelona

Aula abierta, NGO for the defense of universities in Latin America

Association of World Citizens (AWC)

Tricontinental Centre – CETRI (Belgium)

Argentina

Horacio Tarcus, historian

Carmen Elena Villacorta, National University of Jujuy (UNJU), Central American Articulation O Istmo (Argentina)

Belgium

Bernard Duterme, director of CETRI (Centre tricontinental), UCL Louvain, sociologist and journalist. Former university cooperant at UCA

Geoffrey Pleyers, Professor at the Catholic University of Leuven

Éric Toussaint, PhD in political science from the universities of Paris 8 and Liège

Marleen Goethals, Master in Urban and Spatial Planning, Urban Development Research Group, ISTT Research Unit, University of Antwerp

Devanshi Saxena, PhD, Researcher, and Senior Lecturer, Faculty of Law, University of Antwerp

Brazil

Salvador Schavelzon, Professor at the Federal University of São Paulo

Ana Mercedes Sarria Icaza, Professor, Federal University of Río Grande do Sul, Porto Alegre

Vera Bornstein, Professor, Ecole Polytechnique (EPSJV), FIOCRUZ Foundation

Humberto Meza, PhD in Political Science. Researcher at the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro

Canada

Anne-Emanuelle Birn, MA, ScD, Professor, Global Development Studies and Global Health, University of Toronto

Ruth W. Millar, author, former journalist and bookseller

Chile

Pablo Abufom, researcher at the Institute of Anticapitalist Studies Alternativa, editor of the journal Posiciones

Juan Cornejo Espejo

Colombia

José Luis Socarrás Pimienta, Dean of the Faculty of Cultural Heritage Studies

Maria Lucia Rapacci Gomez, Professor, Pontificia Javeriana University, Bogota

María Margarita Echeverry B., Professor, Pontificia Javeriana University, Bogotá

Luis Ramírez Zuluaga, Professor, Institute of Regional Studies (INER), University of Antioquia

Sara Yaneth Fernández Moreno, Colombian teacher, feminist activist, in exile

Catalina Toro, Associate Professor in the Department, Environmental Policy and Law Group – A – Colciencias, Faculty of Law, Political and Social Science, National University of Colombia

Costa Rica

Dr. Mario Zúñiga Núñez, University of Costa Rica, CLACSO Working Group “Violence in Central America”

Dra. Denia Román Solano, professor and researcher at the University of Costa Rica, CLACSO working group “The Central American Isthmus: Peripheral Epistemological Perspectives” O Istmo – Articulación Centroamericanista

Dr. Onésimo Rodríguez Aguilar, Director of the Center for Anthropological Research (CIAN), Lecturer School of Anthropology of the University of Costa Rica

Abelardo Morales Gamboa, National University of Costa Rica

Carlos Sandoval García, National University of Costa Rica

M.Sc. Carolina Sánchez Hernández, School of Sociology, National University of Costa Rica

Celia Barrantes Jiménez, Acting Professor, School of Anthropology, University of Costa Rica

Dr. Jorge Rovira Mas, Professor Emeritus of the School of Anthropology of the University of Costa Rica

María Esther Montanaro Mena, Public Servant, University of Costa Rica

Óscar Montanaro Meza, retired professor, University of Costa Rica

Claudine van Gyseghem Szabo, Retired Professor of Anthropology, University of Costa Rica

Saray Córdoba González, retired professor, University of Costa Rica

Eugenia Solís Umaña, Retired Professor, University of Costa Rica

Dr. Alexis Segura Jiménez, Coordinator of the PhD in Social Sciences, National University of Costa Rica

Elthon Rivera Cruz, President IPEN

Denmark

Susanne Lysholm Jensen, Syddansk University, Roskilde University Center (RUC), , UPOLI, Nicaragua

Else Mikél Jensen, Spanish Master’s degree, University of Aarhus

Alejandro Parellada, IWGIA (International Organization for the Rights of Indigenous Peoples)

Gorm Rasmussen, writer and journalist, member of PEN

Gertrud Permin

Jan Franck, Financial Advisor

El Salvador

Dr. Carlos Gregorio López, Bachelor of History Teacher, University of El Salvador

Karina Esther Grégori Méndez, WG Feminisms, Resistances and Emancipation Processes-CLACSO, Central American Sociological Association-ACAS

Jorge Alberto Juárez Ávila, historian

Spain

Fernando Harto de Vera, former Vice-Rector of the Faculty of Political Science at the Complutense University, Madrid

Jaime Pastor, professor of political science and editor of the journal Viento Sur

Marcos Roitman Rosenmann, Professor, Complutense University, Madrid

Juan José Tamayo, Secretary General of the Spanish Association of Theologians of the Ignacio Ellacuría Chair of Theology and Religious Studies, Carlos III University, Madrid

Lola Cubells Aguilar, Professor of Constitutional Law, Jaume I University (Castellón de la Plana)

Teresa Virgili Bonet, Professor of Economic Policy, University of Barcelona, Doctor Honoris Causa of UNAN Managua

Benjamín Bastida Vilâ, Professor Emeritus of the University of Barcelona, Honoris causa of UNAN Managua

Dra. Aurelia Mañé-Estrada, University of Barcelona

Carmen de la Cámara, Retired Professor at the University of Barcelona

Rafael Grasa Hernández, Professor of International Relations at the Autonomous University of Barcelona

Francesc Carmona Pontaque, Professor, Department of Microbiology, Genetics and Statistics, Faculty of Biology, University of Barcelona

Xavier Martí González, Associate Professor of World Economics, University of Barcelona

Albert Puig, Professor, Universitat Oberta de Catalunya

José Ignacio González Faus, Lluís Espinal Foundation, Catalonia

Sara Porras Sánchez, Professor of Sociology, Complutense University, Madrid

Omar de León Naveiro, S.D. Applied, Public and Political Economics, Complutense University, Madrid

Rafael Díaz-Salazar, Faculty of Political Science and Sociology, Department of Applied Sociology, Somasaguas Campus, Madrid

Rafael Ruiz Andrés, Professor of Sociology, Complutense University, Madrid

Ph.D. Juan Ignacio Alfaro Mardones, teacher and researcher, Asturias.

Amparo Madrigal, PhD in Social Psychology from the University of Valencia and former graduate in Psychology from the Central American University of Nicaragua (UCA).

United States

William I Robinson, Professor Emeritus of Sociology, University of California, Santa Barbara

Samuel Farber, Professor Emeritus of Political Science, Brooklyn College, New York University (CUNY)

Mary Ellsberg, Director of the Global Women’s Institute, Washington DC

Dr. Julia Ahmed, Independent Consultant (Sexual Reproductive Health & Rights; Mainstreaming Gender Equality & Health System Strengthening)

Dr. Samira Marty, Binghamton University

Jorge Mauricio Herrera Acuña, Mellon Faculty Fellow, Department of Spanish and Portuguese, Dartmouth College (Hanover)

Ignacio Ochoa, Latin American Studies, San Diego State University

Dr. Tom Hare, University of Notre Dame

María Estela Rivero Fuentes, Doctor of Law, Central American Research Alliance (CARA) Co-Director, Pulte Institute for Global Development, University of Notre Dame

France

Michael Löwy, Emeritus Research Director, CNRS

Eleni Varikas, Professor Emeritus, Paris 8

Henri Saint-Jean, doctor in social psychology Clipsy laboratory of the University of Angers, former trainer at CEFORSE of Managua

Robi Morder, Associate Researcher at Laboratoire Printemps, Université Paris-Saclay

Jean Malifaud, retired professor of mathematics, Paris-Jussieu University

Hubert Krivine, physicist

Antoine Hollard, honorary professor in preparatory class for engineering schools

Pedro Vianna, university teacher, economist, poet, theatre man

Pierre Salama, Professor Emeritus, Sorbonne Paris-Nord University

Christian Tutin, Professor Emeritus of Economics, University Paris-Est Créteil

Roland Pfefferkorn, Professor Emeritus of Sociology, University of Strasbourg

Samy Johsua, Professor Emeritus, University of Aix-Marseille

Philippe Enclos, lecturer and researcher in law, retired, University of Lille

Jean-Paul Bruckert, historian, emeritus university professor, Besançon

Jacques Fontaine, geographer, professor emeritus, University of Besançon

Silvia Fabrizio-Costa, Professor Emeritus of Italian Language, Literature and Civilization, University of Caen

Djaouidah SEHILI, sociologist, professor, Institut national supérieur du professorat et de l’éducation (INSPE), head of the Department of Human and Social Sciences, Centre d’études et de recherches sur les emplois et les professionalisations (CEREP), Université Reims-Champagne-Ardenne

Laurence Proteau, sociologist, Associate Professor, University of Picardy/ EHESS/France

Frank La Brasca, retired professor, Centre d’études supérieures de la Renaissance de l’Université de Tours

Georges Ubbiali, sociologist, University of Burgundy

Serge Aberdam, researcher at INRA, retired

Hubert Cochet, professor, AgroParistech, UFR Comparative Agriculture and Agricultural Development

Dr Christian Castellanet, agronomist and ecologist, former scientific director of GRET, Nogent-sur-Marne

Isaline Réguer, agronomist

Michel Dulcire, retired agricultural development researcher

Florent Maraux, agronomist, former aid worker in Nicaragua

Laurent Levard, contract professor at the University of Paris-Saclay and the Sorbonne Institute of Development Studies, former professor and researcher at UCA

François Doligez, associate researcher at the University of Paris-Pathéon-Sorbonne, former cooperant in Nicaragua

Anaïs Trousselle, researcher in geography, former visiting PhD student at the Nitlapán Institute (UCA)

Odile Hoffmann, Research Director, Geographer at the Institut de recherche pour le développement (IRD)

Eric Léonard, Research Director at the Institut de la recherche pour le développement (UMR SENS), Montpellier

Lucile Medina, Professor of Geography, Université Paul-Valéry Montpellier 3, Laboratoire de géographie et d’aménagement de Montpellier (LAGAM)

Jean-Marc Touzard, Research Director, INRAE, University of Montpellier

Catherine Samary, researcher in political economy, member of the French Association for Research on the Balkans

Jules Falquet, Professor of Philosophy, University of Paris 8 – Saint-Denis

Fabien Granjon, sociologist, University of Paris 8

David Dumoulin, sociologist, Institut des Hautes Etudes de l’Amérique latine (IHEAL) Université Sorbonne nouvelle

Sébastien VELUT, Professor of Geography, Institut des Hautes Etudes de l’Amérique latine, Sorbonne Nouvelle University

Juliette Dumont, Researcher, Institut des Hautes Etudes de l’Amérique latine, Université Sorbonne Nouvelle

Mathilde Allain, Researcher, Institut des Hautes Etudes de l’Amérique latine, Sorbonne Nouvelle University

Capucine Boidin, Researcher, Institut des Hautes Etudes de l’Amérique latine, Université Sorbonne Nouvelle

Carlos Quenan, Researcher Institut des Hautes Etudes de l’Amérique latine, Sorbonne Nouvelle University

Marie Laure Geoffray, Researcher, Institut des Hautes Etudes de l’Amérique latine, Université Sorbonne Nouvelle

Laurent Faret, Professor, CESSMA, Université Paris-Cité

Delphine Lacombe, sociologist and political scientist, researcher at CNRS, CEMCA, USR 3337

Natacha Lillo, Professor of Contemporary History of Spain, Paris-Cité University

Carlos Agudelo, associate sociologist at the University of Paris

Michel Cahen, CNRS Emeritus Research Director, Sciences-Po Bordeaux

Pierre Blanc, lecturer and researcher in geopolitics, Sciences-Po Bordeaux, Bordeaux Sciences agro

Franck Gaudichaud, Professor of Latin American History, Jean-Jaurès Toulouse University

Olivier Neveux, Professor, ENS Lyon

Laurent Ripart, professor at Savoie Mont Blanc University (Chambéry)

Dr. Catherine Bourgeois, URMIS associate researcher, Paris-Nice

Daniela García, researcher in the energy industry

Christophe Aguiton, retired researcher in the telecommunications sector

Pablo Krasnopolsky, teacher

Robert March, Teacher, ENSAPVS

Patrick Silberstein, MD, editor of Syllepse

Dr Christine d’Yvoire-Doligez, pediatrician

Jean Puyade, retired language teacher

Patricia Pol for the International Knowledge for All Collective (IDST)

François Laroussinie, computer scientist, University of Paris-Cité, SNESUP-FSU

Jean Pierre Debourdeau, former member of the FSU departmental office (Côte-d’Or)

Maurice Brochot, Departmental Manager (Côte-d’Or) of the FSU

Josette Tract, academic, member of SNESup

Philippe Cyroulnik, Art Critic (AICA)

Finland

Dr. Florencia Quesada Avendaño, Associate Professor of Latin American Studies, University of Helsinki

Barry K. Gills, Professor of Global Development Studies, University of Helsinki

Guatemala

Ana Silvia Monzón, sociologist

Prof. Simona Violetta Yagenova, FLACSO Guatemala

Carmen Rosa de León-Escribano, sociologist

Honduras

Efraín Aníbal Díaz Arrivillaga, economist, consultant and university teacher, UNAH

Miguel Alonzo Macías, Professor-Researcher, Department of Sociology, UNAH

Mexico

Dr. Gilberto López y Rivas, Professor-Researcher, National Institute of Anthropology and History, Morelos Regional Center

Aida Luz López, National Autonomous University of Mexico

Dr. Juan Manuel Sandoval Palacios, coordinator of the permanent seminar of Chicana and Border Studies, Directorate of Ethnology and Social Anthropology INAH

David Fernández Dávalos, Commissioner of the Historical Investigative Mechanism of the Truth Commission 1965-1990

Víctor Manuel González Romero, former Rector General of the University of Guadalajara, member of the Mexican Academy of Sciences

Verónica Rueda Estrada, Autonomous University of the State of Quintana Roo

Raúl Arístides Pérez Aguilar, Autonomous University of the State of Quintana Roo

Adela Vázquez Trejo, Autonomous University of the State of Quintana Roo

Enrique Joel Burton Mendoza, Teacher, Autonomous University of the State of Quintana Roo

Dr. Francisco Javier Güemez Ricalde, Professor-Researcher, Autonomous University of the State of Quintana Roo

Dra. Natalia Armijo Canto, Research Professor, Autonomous University of the State of Quintana Roo

Horacio Pablo Espinosa Coria, Autonomous University of the State of Quintana Roo

Emilia Velázquez Hernández, CIESAS Golfo

María Teresa Rodríguez, teacher-researcher, CIESAS-Golfo

Dolores Figueroa Romero, University Professor CONACYT-CIESAS, Mexico City

Regina Martínez Casas, teacher-researcher, CIESAS, Mexico City

Carolina Rivera Farfán, CIESAS

Xochitl Leyva Solano, CIESAS Sureste y GTCuter Clacso

Sabrina Melenotte, CIESAS/IRD

Delphine Prunier, Institute of Social Research, National Autonomous University of Mexico

Rosa Torras Conangla, National Autonomous University of Mexico, Mérida, Yucatán

Dra. Eva Leticia Orduña Trujillo, Researcher, Center for Research on Latin America and the Caribbean, National Autonomous University of Mexico

Dra. Alicia Castellanos Guerrero, UAM

Jorge Alonso, National Researcher Emeritus

Dr. Mauricio Genet Guzmán Chávez, Full Research Professor B, Anthropological Studies Program

Dra. Alma Amalia González Cabañas, Researcher B, UNAM

Cristóbal Santos Cervantes, Agricultural Engineer specializing in Rural Sociology, Autonomous University of Chapingo

Elisa Cruz Rueda, lawyer and anthropologist, research professor at the School of Management and Indigenous Self-Development, Autonomous University of Chiapas

Gisela Zaremberg, FLACSO teacher-researcher

Dra. Mónica Toussaint, teacher-researcher, Mora Institute

Bruno Baronnet, sociologist, University of Veracruzana

Yerko Castro Neira, Research Professor, Department of Social and Political Sciences, Iberoamerican University

Carlos Mario Castro, Professor at the Iberoamerican University

Cecilia Zeledón, alumnus of the Ibero-American University of Puebla

Enrique Lavín, alumnus of the Iberoamerican University CDMX

Dr. Jorge Ceja Martínez, University of Guadalajara, former cooperant in Nicaragua (1984-1985)

Dr. Miriam Cárdenas Torres, University of Guadalajara, former aid worker in Nicaragua (1984-1985)

Salvador Lazcano Díaz del Castillo, civil engineer, consultant in the field of geotechnical engineering and holder of a master’s degree from ITESO and Pan American Universities of Guadalajara

Dr. Alberto Bayardo Pérez Arce, Professor, Department of Sociopolitical and Legal Studies, ITESO, Guadalajara

Luis Ignacio Román Morales, teacher, ITESO, Guadalajara

Efrén Carrillo L, Former student of the Society of Jesus

Ramón Martínez Coria, Chairman of the Board of Directors of the Forum for Sustainable Development

Rafael Ibarra Garza, Coalition for Academic Freedom in the Americas

Luis de Tavira, playwright, theatre director, La Casa del Teatro. A.C., Mexico

Alfonso Castillo S. M., Director of the Union of Efforts for the A.C. Campaign

Gabriela Fenner, Institute of Geography for Peace

Juan Carlos Núñez Bustillos, journalist

Fernando Valadez Pérez, psychoanalyst

Salvador Alonso, Anaesthetist

José Luis Hernández Ayala, member of the Mexican Union of Electricians

Nicaragua

Cristian Ernesto Medina Sandino, former Rector of UNAN-León y UAM

MSc. Marco Aurelio Peña. Economist, lawyer and academic. Former professor at Paulo Freire University and Juan Pablo II Catholic University, associate researcher at the Center for Transdisciplinary Studies of Central America (CETCAM) and member of the Board of Directors of the Central American Philosophical Association (ACAFI).

Diego, former student at UCA

María Castillo, university professor in exile

Azahalia Solís Román, lawyer, feminist and human rights defender, in exile

Haydee Castillo, former president of the Leadership Institute Foundation of Las Segovias – ILLS, and member of the Women’s Initiative for the Defense of Human Rights in Nicaragua, in exile

Netherlands and Aruba

Margreet Zwarteveen, Professor of Water Governance, IHE Delft Institute for Water Education and University of Amsterdam

Dr. Julienne Weegels, researcher and professor at CEDLA, University of Amsterdam

Irene van Staveren, Professor of Pluralistic Development Economics, International Institute for Labour Studies, Erasmus University, Rotterdam

Dr. Max Spoor, Professor Emeritus, International Institute for Labour Studies, Erasmus University, Rotterdam

Nanneke Winters, Associate Professor of Migration and Development, International Institute for Labour Studies (ISS) – The Hague

Helena Pérez Niño, Associate Professor, International Institute for Labour Studies (ISS) – The Hague

Georgina M Gómez, Associate Professor of Local Development, Governance and Development Policy, President of the Research Association on Monetary Innovation and Complementary Currencies.

Luisa González, PhD student at the Centre for Research and Documentation on Latin America, University of Amsterdam

Marianne Eelens, Public Health Consultant, Aruba

Paraguay

Fernando Masi, Director of the Centre for Analysis and Dissemination of the Paraguayan Economy – CADEP

Lilian Soto, CLACSO Working Group “Gender, (in)equality and rights in tension”

United Kingdom

Lyla Mehta, Professor, Institute of Development Studies

Sweden

Eva Zetterberg, former Swedish Ambassador to Nicaragua (2003-2008), former Deputy Speaker of the Swedish Parliament 1998-2002

Switzerland

Stéfanie Prezioso, Professor of History, University of Lausanne

Sébastien Guex, Honorary Professor, University of Lausanne

Janick Schaufelbuehl, Associate Professor, University of Lausanne

Lene Swetzer, Anthropologist, Geneva Graduate Institute

Venezuela

Nelson Rivas, researcher at the Human Rights Observatory of the University of the Andes

Alexis Mercado, Professor, Central University of Venezuela

Alba Carosio, Full Professor, Central University of Venezuela

Hebe Vessuri, Central University of Venezuela

This is a reply to Gilbert Achcar, following his

This is a reply to Gilbert Achcar, following his

A few days ago, Democratic Socialists of America’s online publication ran my article about my recent visit to Ukraine. It was entitled “Notes from Kyiv: Which side are we on?”

A few days ago, Democratic Socialists of America’s online publication ran my article about my recent visit to Ukraine. It was entitled “Notes from Kyiv: Which side are we on?”

Oppenheimer (directed by Christopher Nolan, based on the book American Prometheus: The Triumph and Tragedy of J. Robert Oppenheimer, written by Kai Bird, of The Nation, and Martin J. Sherwin, a historian of foreign policy who died in 2021) is a morality play in which big personalities forcefully negotiate conflicting world views during and after the frantic drive to build the atomic bomb that would beat Hitler.

Oppenheimer (directed by Christopher Nolan, based on the book American Prometheus: The Triumph and Tragedy of J. Robert Oppenheimer, written by Kai Bird, of The Nation, and Martin J. Sherwin, a historian of foreign policy who died in 2021) is a morality play in which big personalities forcefully negotiate conflicting world views during and after the frantic drive to build the atomic bomb that would beat Hitler.

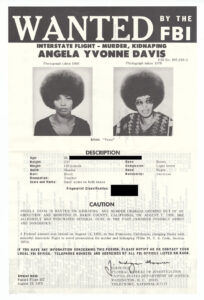

This is the second of a series of article about Black political candidates for the two highest offices of president and vice-president of the United States. The idea of writing this series originally begun when Cornel West announced his candidacy, the story of Black political candidates for the highest offices take on a new significance in light of Kamala Harris’ current campaign. This is the list of candidates that we discuss in this series, though the four candiates of 1968 are discussed in one article.

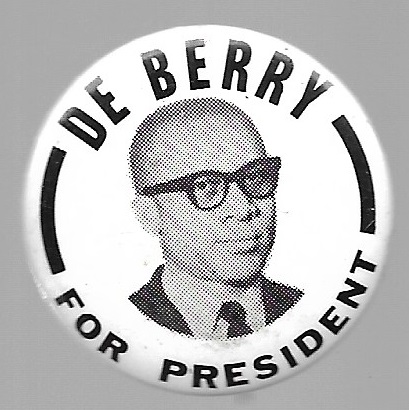

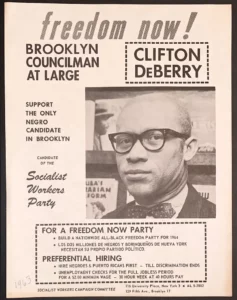

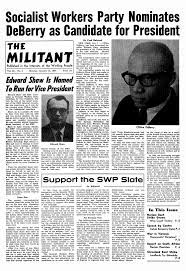

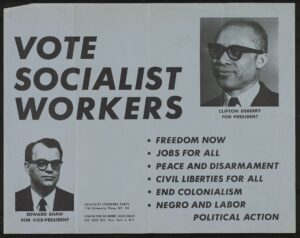

This is the second of a series of article about Black political candidates for the two highest offices of president and vice-president of the United States. The idea of writing this series originally begun when Cornel West announced his candidacy, the story of Black political candidates for the highest offices take on a new significance in light of Kamala Harris’ current campaign. This is the list of candidates that we discuss in this series, though the four candiates of 1968 are discussed in one article. In the early 1960s, the SWP began to revitalize by relating to the Black civil rights movement and supporting the Cuban Revolution of 1959 through the Fair Play for Cuba Committee. Dobbs and other SWP leaders visited Cuba and DeBerry played a major role in the attempt to develop relations to the civil rights movement. In the early 1960s, DeBerry became the branch organizer of the Socialist Workers Party in New York City and later the New York State organizer. In 1963, he ran as the party’s candidate for the Brooklyn Councilman-at-Large and he also conducted a national speaking tour discussing the Black “Freedom Now Struggle” and supporting the Freedom Now Party that the SWP had created.

In the early 1960s, the SWP began to revitalize by relating to the Black civil rights movement and supporting the Cuban Revolution of 1959 through the Fair Play for Cuba Committee. Dobbs and other SWP leaders visited Cuba and DeBerry played a major role in the attempt to develop relations to the civil rights movement. In the early 1960s, DeBerry became the branch organizer of the Socialist Workers Party in New York City and later the New York State organizer. In 1963, he ran as the party’s candidate for the Brooklyn Councilman-at-Large and he also conducted a national speaking tour discussing the Black “Freedom Now Struggle” and supporting the Freedom Now Party that the SWP had created. At the SWP’s Convention in January 1964, Farrell Dobbs nominated DeBerry to be the party’s presidential candidate. The vote for DeBerry was unanimous, the party’s newspaper, The Militant, reported. The Militant noted: “DeBerry is the first Negro in U.S. history to be chosen by a political party as its presidential candidate.”

At the SWP’s Convention in January 1964, Farrell Dobbs nominated DeBerry to be the party’s presidential candidate. The vote for DeBerry was unanimous, the party’s newspaper, The Militant, reported. The Militant noted: “DeBerry is the first Negro in U.S. history to be chosen by a political party as its presidential candidate.”

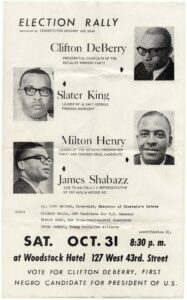

Still, despite the FBI’s dirty tricks, the campaign continued. On Saturday, October 31 at the Woodstock Hotel in New York City DeBerry spoke with three other Black men Slater King was the head of the SWP-led Freedom Now Party in Albany, Georgia and a Milton Henry a Freedom Now Party candidate for Congress, but more importantly James Shabazz, an aid to Malcolm X and representative of Muslim Mosque Incorporated. Other SWP members would establish a relationship with Malcolm X before his assassination in 1965. In the end, DeBerry got 32,327 or 0.5 percent of the votes cast, little more than half of Dobbs’ campaign four years earlier. The Freedom Now Party which DeBerry had been active in building died the following year.

Still, despite the FBI’s dirty tricks, the campaign continued. On Saturday, October 31 at the Woodstock Hotel in New York City DeBerry spoke with three other Black men Slater King was the head of the SWP-led Freedom Now Party in Albany, Georgia and a Milton Henry a Freedom Now Party candidate for Congress, but more importantly James Shabazz, an aid to Malcolm X and representative of Muslim Mosque Incorporated. Other SWP members would establish a relationship with Malcolm X before his assassination in 1965. In the end, DeBerry got 32,327 or 0.5 percent of the votes cast, little more than half of Dobbs’ campaign four years earlier. The Freedom Now Party which DeBerry had been active in building died the following year.

While the coup plotters in no way represent an alternative for Niger, the economic sanctions and threats of military intervention by ECOWAS (Economic Community of West African States), backed by Macron, are a real danger for the population.

While the coup plotters in no way represent an alternative for Niger, the economic sanctions and threats of military intervention by ECOWAS (Economic Community of West African States), backed by Macron, are a real danger for the population.

Detroit in the 1980s was the site of a bonanza of large-scale developments pushed by Democratic Party Mayor Coleman Young in order to revive the cities’ flagging economy. Young had made a name for himself as a radical, and according to conservative historians he

Detroit in the 1980s was the site of a bonanza of large-scale developments pushed by Democratic Party Mayor Coleman Young in order to revive the cities’ flagging economy. Young had made a name for himself as a radical, and according to conservative historians he

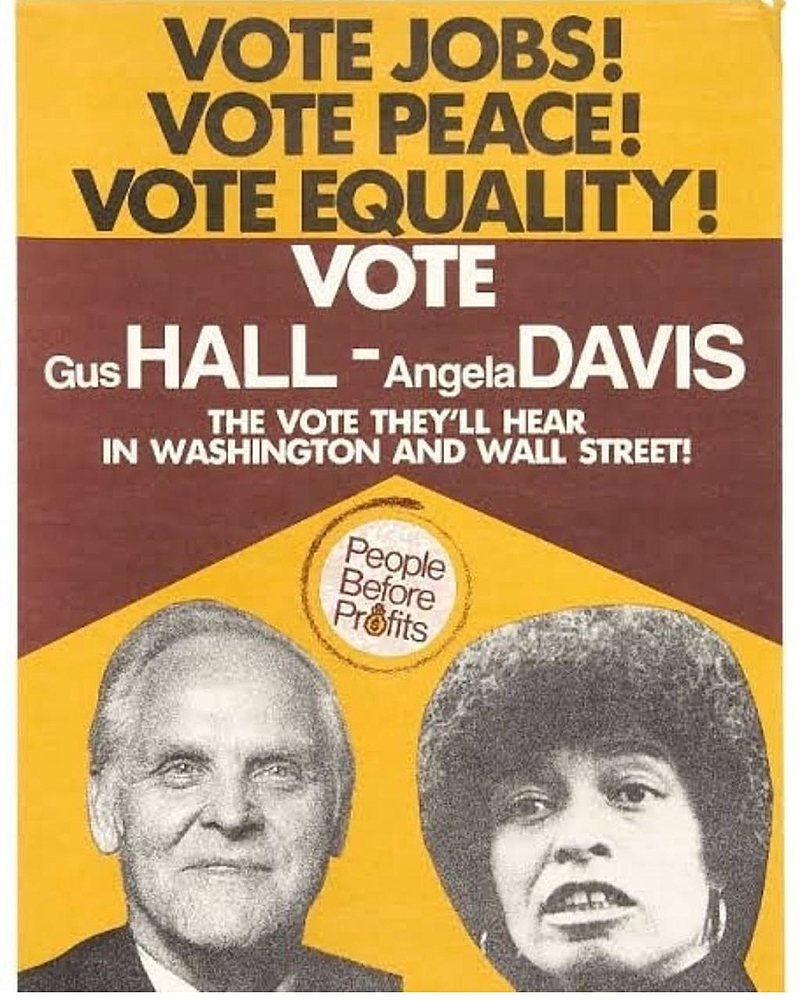

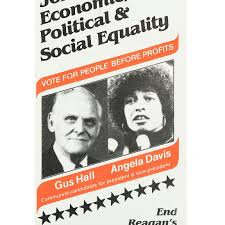

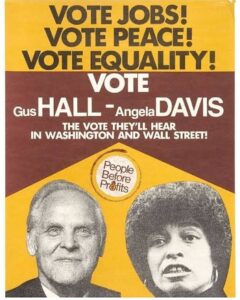

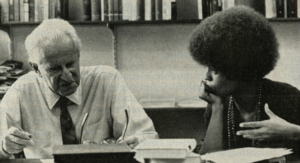

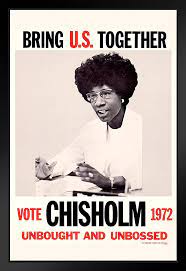

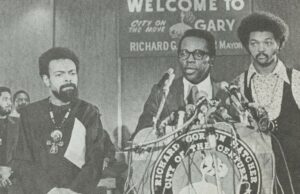

This is the fifth of a series of article about Black political candidates for the two highest offices of president and vice-president of the United States. The idea of writing this series originally begun when Cornel West announced his candidacy, the story of Black political candidates for the highest offices take on a new significance in light of Kamala Harris’ current campaign. This is the list of candidates that we discuss in this series, though the four candiates of 1968 are discussed in one article.

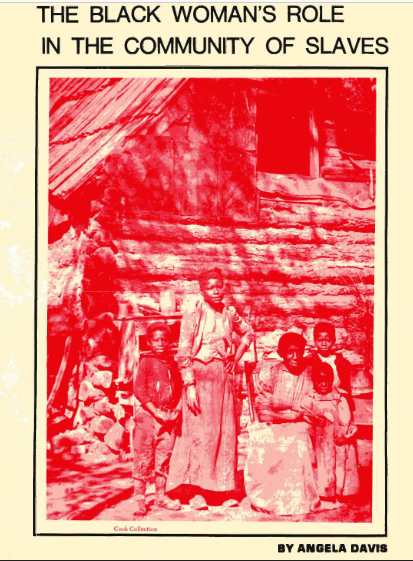

This is the fifth of a series of article about Black political candidates for the two highest offices of president and vice-president of the United States. The idea of writing this series originally begun when Cornel West announced his candidacy, the story of Black political candidates for the highest offices take on a new significance in light of Kamala Harris’ current campaign. This is the list of candidates that we discuss in this series, though the four candiates of 1968 are discussed in one article. In the 1980s, voters had an opportunity to support Black candidates for the nation’s highest offices in two different parties. Angela Davis, for vice-president on the Communist Party ticket in 1980 and 1984, and Rev. Jesse Jackson for president in the Democratic primaries in 1984 and 1988. We look here at Davis’ campaigns.

In the 1980s, voters had an opportunity to support Black candidates for the nation’s highest offices in two different parties. Angela Davis, for vice-president on the Communist Party ticket in 1980 and 1984, and Rev. Jesse Jackson for president in the Democratic primaries in 1984 and 1988. We look here at Davis’ campaigns.

Leading left-wing Russian thinker Boris Kagarlitsky is facing up to

Leading left-wing Russian thinker Boris Kagarlitsky is facing up to

I am thankful to Tom Dale for starting his

I am thankful to Tom Dale for starting his

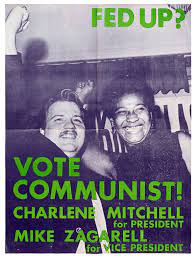

Charlene Mitchell for President

Charlene Mitchell for President Eldridge Cleaver for President

Eldridge Cleaver for President Dick Gregory for President

Dick Gregory for President  Finally, Channing E. Phillips, a man much like Cornel West, was nominated at the Democratic Party Convention. Phillips, Brooklyn born and raised, served in the army during World War II and then studied at Virginia Union University and then Colgate Rochester Crozer Divinity School. He became a professor at Howard University and the pastor of Lincoln Temple, United Church of Christ. He was a local civil rights activist and headed up Robert F. Kennedy’s campaign in Washington, D.C. in 1968. After Kennedy’s assassination, Phillips was nominated for president as a favorite son candidate, receiving 68 votes, far behind Humphrey, McCarthy, and George McGovern.

Finally, Channing E. Phillips, a man much like Cornel West, was nominated at the Democratic Party Convention. Phillips, Brooklyn born and raised, served in the army during World War II and then studied at Virginia Union University and then Colgate Rochester Crozer Divinity School. He became a professor at Howard University and the pastor of Lincoln Temple, United Church of Christ. He was a local civil rights activist and headed up Robert F. Kennedy’s campaign in Washington, D.C. in 1968. After Kennedy’s assassination, Phillips was nominated for president as a favorite son candidate, receiving 68 votes, far behind Humphrey, McCarthy, and George McGovern.

Gilbert Achcar has long been one of the more nuanced socialist commentators on foreign affairs. In particular, he has considered the difficulties associated with the use of Western hard power in situations where one function of that power has been to protect human life or progressive formations. Whether one agrees or not in any given case, no one can accuse him of delivering off-the-peg answers.

Gilbert Achcar has long been one of the more nuanced socialist commentators on foreign affairs. In particular, he has considered the difficulties associated with the use of Western hard power in situations where one function of that power has been to protect human life or progressive formations. Whether one agrees or not in any given case, no one can accuse him of delivering off-the-peg answers.