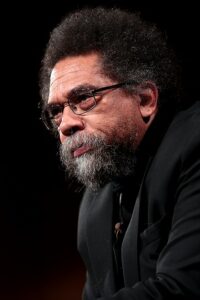

Cornel West announced in early June that he was running for president of the United States as the candidate for the People’s Party and then as aspiring to be candidate of the Green Party. In Part 1 of this article, we looked at the reaction of the left, with comments from DSA and Green Party leaders. Here we turn to look at the experience of four Black presidential candidates in 1968.

Cornel West announced in early June that he was running for president of the United States as the candidate for the People’s Party and then as aspiring to be candidate of the Green Party. In Part 1 of this article, we looked at the reaction of the left, with comments from DSA and Green Party leaders. Here we turn to look at the experience of four Black presidential candidates in 1968.

One can certainly imagine that under the right circumstance a campaign by a Black leftist might be a good thing both for the country, for the left, and for Black people. It might address both the economic issues and the racial matters, as well as gender and many other issues so important to improving the lives of millions, to defending and expanding democracy, and to building a multiracial, multiethnic working-class party. Yet so far, we have no such experience.

Candidates run for office for various reasons. Some will run for office to win, even if their chances are slim. Others, knowing that they cannot win, will run to win enough votes to influence a major party’s political platform and direction. Some run to build the social movements. Some will run for office to recruit to their party. Some run to count votes as a measure of their party’s influence in society and to see if that influence is growing. All of these are legitimate and common in democracies all over the world, though in the American political system, without proportional representation, with first-past-the-post elections, and winner take all elections in 48 of 50 states, one must be cognizant that minor party candidates can be spoilers who may contribute to the victory of a more conservative major party candidate. The reality, much as we hate it, is that a vote for a leftist party will likely subtract a vote from the Democratic Party and help to elect a rightwing Republican.

Given this, Black political candidates on the left found themselves in the same situation as other leftist parties and candidates. If they run independent campaigns, they are shunned as spoilers and receive few votes. If they run campaigns in the Democratic Party, they find themselves checked by the party’s structures, processes, and politics. The way out of this dilemma, some believe, is an “inside/outside strategy,” that is to work for a candidate within the Democratic Party while building social movements to pressure that candidate and the party from without. This has never proved very successful. Yet others argue that building a leftist force in the Democratic Party can lead to a “dirty break” with it in the future, creating a major third party.

Many of those of us on the left believe that it will take a massive, powerful social movement of the country’s working people to bring about a reconfiguration and realignment of political parties and to create a working-class political party. We will say more about this in the conclusion to this series of articles. Let’s look now at the actual experience of several Black leftist candidates over the last 60 years. In this part we look at the Black presidential candidates of 1968.

1968 – Four Black Candidates

The annus mirabilis of the left around the world, 1968, saw four Black candidates nominated for president of the United States: Charlene Mitchell on the Communist Party line, Eldridge Cleaver with the Peace & Freedom Party, and Dick Gregory as a write-in candidate, and Channing Emery Phillips as a Democrat. the first three, each had a distinct political position and style, represented the same strategic approach, running on a minor third-party line. Charlene Mitchell’s campaign seems to have been intended to lift the profile of the Communist Party and to recruit to it, while both Cleaver and Gregory—who had been rivals for the Peace and Freedom Party nomination—sought to build the anti-war and civil rights movement. Phillips’ nomination was purely honorific in cognition of his work for Robert F. Kennedy and the Democrats. It was the bestowing of an honor, not a campaign. We examine these candidates’ experience to see what they can teach us.

Charlene Mitchell for President

Charlene Mitchell for President

We begin this discussion with the first Black woman candidate for president in U.S. history who ran in 1968 on the Communist Party ticket Charlene Mitchell. Her parents had been part of the great migration moving first to Cincinnati and then to Chicago where she grew up. At 13 she joined American Youth for Democracy, then the youth organization of the Communist Party. Three years later, in 1946, at the age of 16, she had joined the Communist Party that was then a thoroughly Stalinist organization at the height of its influence, when it had 75,000 members, received 100,000 votes for its candidates in national campaigns, and had a periphery of at least a million activists with which it was engaged. But later the party lost momentum, stalled, and began to crumble.

The Communist Party’s problems had begun before Mitchell joined. Thousands of members left the party following the Hitler-Stalin pact of 1939, in which the two totalitarian powers, Nazi Germany and the Stalinist Soviet Union reached non-aggression agreement and subsequently both invaded and divided Poland, which led thousands of members of leave the party. In the 1940s, the CP overcame that setback and recruited tens of thousands of new members as it led both labor organizing drives and Black civil rights struggles. But then during World War II, it lost some Black members when it endorsed the labor union’s no-strike pledge and tried to restrain the Black civil rights movement, fearing it could interfere with war production.

Mitchell joined at the end of the war, during the party’s peak, but in the post-war period the party faced several crises. The new leader of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, Nikita Khrushchev, gave a speech in February of 1956 denouncing Joseph Stalin for crimes against “fellow Communists and the Soviet People.” That was followed in October of 1956 by the Soviet Union’s invasion of Hungary to crush a workers’ rebellion against the Communist government there. These two events led tens of thousands of CPUSA members to tear up their membership cards and leave the party.

During this same period, the Cold War and the anti-Communist crusades of Senator Joseph McCarthy and others led many Communists to leave the party for fear of losing their jobs or even going to prison. So, in the decade of the 1950s, now an organization under siege, the CP declined to about 7,000 members, a membership riddled with FBI informers and divided into rival factions.

When in the 1960s the Cold War ended and a New Left arose, the new young activists were alienated by the Communist Party’s ongoing loyalty to the Soviet Union and orientation to the labor union bureaucracy and the Democratic Party. Leftists took their political activism elsewhere, mostly to liberal, anti-war candidates in the Democratic Party or, as the Sixties unfolded, to Students for a Democratic Society (SDS), the Black Panther Party, or small Trotskyist and Maoist groups. This, then, was the general situation when Mitchell, who never publicly differed with or criticized the Communist Party’s politics (something she wouldn’t do until 1986) ran for president in 1968. She had to defend the CP’s history of deeply flawed domestic and international politics–such as the no-strike pledge in World War II and the Soviet crushing of the Hungarian Revolution. And she had to break through the persistent anti-Communism of politicians, the media, and much of the public that instinctively rejected a one-party dictatorship. She ran at the peak of leftist and social movements in the United States and around the world, which was ironically also the nadir of the influence of the CPUSA.

Charlene Mitchell did not expect to receive many votes, largely because of the onerous process of gathering petition signatures to get on the ballot. Nevertheless, she thought it important to get the Communist Party’s ideas before the public. Though there were also little support for the CP because it was not part of the radical movements and remained oriented to the labor bureaucracy and the Democratic Party. So, in 1968, as Black urban rebellions spread to scores of cities, anti-war protests grew into the hundreds of thousands demanding “Out Now!”, and the women’s liberation movement emerged, the Communist Party appeared on the ballot in only four states and Mitchell and her running mate Michael Zagarell, received a national total of only 1,000 votes. To put this campaign and the others we will consider into perspective, consider that Republican Richard Nixon won the election with 31.7 million votes, Democrat Hubert Humphrey came in second with 31.2 million, and George Wallace, notorious defender of racial segregation in the South, received almost 10 million or 13.5 percent of all votes cast. For Mitchell and the CPUSA, the campaign was a debacle.

Mitchell’s obituary in the New York Times says that “her candidacy put a new face on the Communist Party,” but that is overly generous. The results suggest that her campaign which generated so little resonance could not have advanced the Communist Party, the Black movement, or American society. Though her later defense of philosopher and fellow CP member Angela Davis may well have helped the party.

Davis had been arrested in 1970, charged with providing weapons used in the killing of a Marin County judge as three Black men on trial were also killed.. Mitchell organized Davis’ successful defense, and she was acquitted in 1972. Based on that experience Mitchell then established the National Alliance Against Racist and Political Repression.

One has to ask: What was the point of Mitchell’s campaign? Was it worth it? What did it accomplish? In 1968, Mitchell’s national total of 1,000 votes demonstrated that she and her party were utterly irrelevant in American politics. Her candidacy was too insignificant to label her a spoiler who might have jeopardized the Democratic Party candidate Hubert Humphrey. In any case, much of the left at that time disdained Humphrey and supported peace candidate Eugene McCarthy, or Robert Kennedy, who was assassinated during the campaign. Her campaign principally revealed the political insignificance of the Communist Party.

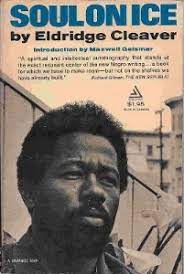

Eldridge Cleaver for President

Eldridge Cleaver for President

Far more interesting and somewhat more significant left third party candidates in 1968 were Eldridge Cleaver and Dick Gregory. Both Cleaver and Gregory were involved in the Peace and Freedom Party, an expression of the anti-war movement (“Peace”) and the civil rights movement (“Freedom”). Founded in 1967, through the collaboration of small far left parties like the International Socialists and the Bay Area Revolutionary Union and the Black Panthers, both Cleaver and Gregory vied for the nomination. The new party chose Eldridge Cleaver as its presidential candidate in California, but Gregory, who had left P&F, nonetheless claimed to represent the party as a write-in candidate. We turn first to Cleaver.

Cleaver’s parents had migrated from Arkansas to California when he was a child, and he grew up in Los Angeles. He spent eight years in prison for rape and assault with intent to murder, from 1958 until 1966 when he was paroled. In prison, he read the Communist Manifesto. Out of prison, he joined the newly-formed Black Panther Party and soon became one of its leaders at a time when it had 2,000 members in several cities, a large following among young Black people, and a national reputation as a militant armed defender of Black rights and revolutionary organization. His book Soul on Ice (1968), which he had written three years before in Folsom Prison to describe the Black experience, “the colonization of the Black soul,” was well received, as a result of which he gained a national reputation among left and intellectual circles.

When nominated for president in 1968, Cleaver, as a leader of the Black Panther Party, had a real base in California’s Black communities. Beyond that, he represented the leftwing of the broader Black movement. Because he would not be 35 by the time of the election, some states disqualified him from the ballot. Still, he won only 36,571 votes, a minuscule percentage of the total. (I, then 23 years old, cast my first presidential vote for Cleaver that year.) A decade later, Cleaver had moved into the rightwing of the Republican Party, but the experiment of which he had been the public face was the token of what might have been a real mass party in America fighting for a foreign policy of peace and a domestic policy of freedom and justice. But few in the movement were prepared to break with the Democrats.

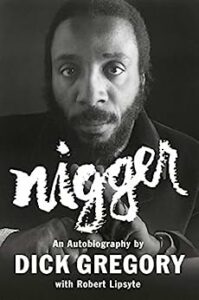

Dick Gregory for President

Dick Gregory for President

Dick Gregory also ran his campaign for president as an expression of the Black freedom and anti-war movements. Funny, angry, and brilliant at political debate, he had a popular following as a stand-up comedian, author, and activist who was often on the frontline of the struggle.

Gregory was born into a poor family in St. Louis, Missouri. A track star at Sumner High School, he won a scholarship to Southern Illinois University, where he set track records as the outstanding athlete of 1953. Drafted in 1954, he began his stand-up career in Army talent shows. In 1961, he got a big break when Hugh Hefner, publisher of Playboy magazine and a liberal, hired Gregory to perform at the Playboy Club. Gregory not only performed. He also produced LP records of his comedy act. Meanwhile, Gregory began to write; his book, Nigger: An Autobiography (1964), eventually sold over a million copies.

Gregory divided his time between his career and the civil rights movement; he was jailed several times, engaged in hunger strikes, and while trying to calm the situation during the 1965 Watts rebellion, he was shot in the leg. A fighter against racism and an opponent of the Vietnam War, Gregory felt that the movement had to become political and he was willing to start the process. In 1967, Gregory ran as a write-in candidate for mayor of Chicago against notorious machine politician Richard J. Daley.

Gregory then decided to run as an independent write-in presidential candidate, but he was also offered the ballot line of several small independent parties in different states, which he accepted. Listening to him speak at UCLA in May 1968, one can hear not only his acerbic comedy, but also his anger, and also his hope for the future based on the young people, whom he saw as the country’s greatest moral force. He won 47,097 votes, more than Cleaver’s 36,623 and Charlene Mitchell’s 1,000. Gregory remained a radical activist for decades.

All three of these campaigns shared the common problem of being either carried out by very small, weak parties, or as write-in campaigns. Perhaps an independent Black party might be much more successful, but it would have to be larger, stronger, and better funded than these were, since most voters feel they would be wasting their vote on a small party. Mitchell’s campaign had the added problem that it was principally a campaign of the Communist Party, which was still viewed as a pariah by many, either because of the anti-Communist campaigns of the two previous decades, or because some voters of various races including many leftists, rejected the Communist model of an authoritarian state. Cleaver and Gregory, meanwhile, were each trying to give expression to the Black freedom and anti-war movements, but neither movement was big enough, strong enough, or united enough to create the kind of party that they needed.

Finally, Channing E. Phillips, a man much like Cornel West, was nominated at the Democratic Party Convention. Phillips, Brooklyn born and raised, served in the army during World War II and then studied at Virginia Union University and then Colgate Rochester Crozer Divinity School. He became a professor at Howard University and the pastor of Lincoln Temple, United Church of Christ. He was a local civil rights activist and headed up Robert F. Kennedy’s campaign in Washington, D.C. in 1968. After Kennedy’s assassination, Phillips was nominated for president as a favorite son candidate, receiving 68 votes, far behind Humphrey, McCarthy, and George McGovern.

Finally, Channing E. Phillips, a man much like Cornel West, was nominated at the Democratic Party Convention. Phillips, Brooklyn born and raised, served in the army during World War II and then studied at Virginia Union University and then Colgate Rochester Crozer Divinity School. He became a professor at Howard University and the pastor of Lincoln Temple, United Church of Christ. He was a local civil rights activist and headed up Robert F. Kennedy’s campaign in Washington, D.C. in 1968. After Kennedy’s assassination, Phillips was nominated for president as a favorite son candidate, receiving 68 votes, far behind Humphrey, McCarthy, and George McGovern.

Considering that 1968 was the apogee of the social movements of the second half of the twentieth century, the experiences of the four Black candidates that we have considered were disappointing. Many factors no doubt contributed to their failure to find a mass following. They were Black in a racist society where many white at that time would have refused to even consider a Black candidate. These candidates stood on the leftwing of American politics, and even though that was the time of its greatest strength, the left still represented only a small percentage of Americans. The two-party political system and state laws, the difficulty of other parties getting on the ballot, was a serious obstacle. The media often marginalized third party candidates and frequently denied them a role in debates. Finally, of course, the capitalists put up vast sums to support the major party candidates, while the opponents could only raise small amounts from the occasional wealthy donor and the grassroots of the movements.

The next part in this series will look at the experiences of two Black women candidates, Shirley Chisholm for president and Angela Davis for vice-president in the 1970s and 80s.

The next article in this series will look at the experience of Shirley Chisholm

[Thanks to Bill Fletcher and Michael Letwin for reading and commenting on this article. I alone am responsible for the views expressed here and for any errors. – DL]

Leave a Reply