Silvio Berlusconi has died at the age of 86. In early May, he spoke from his hospital room at the Forza Italia Congress, recalling “his” glorious years, when he fought to “save democracy and freedom” from “communism.” Retracing the history of his party, from its entry into politics in 1994, he said that Forza Italia was the backbone of Giorgia Meloni’s government. He will undoubtedly leave a lasting mark.

Silvio Berlusconi has died at the age of 86. In early May, he spoke from his hospital room at the Forza Italia Congress, recalling “his” glorious years, when he fought to “save democracy and freedom” from “communism.” Retracing the history of his party, from its entry into politics in 1994, he said that Forza Italia was the backbone of Giorgia Meloni’s government. He will undoubtedly leave a lasting mark.

A few years ago, Antonio Gibelli, a specialist in the First World War, ventured to write a short essay entitled Berlusconi passato alla storia, literally Berlusconi entered history. At the same time, other historians, experts on the Fascist period and its aftermath, and among the sharpest minds in Italian historiography, were also interested in the Milanese politician: Gabriele Turi, Nicola Tranfaglia, Paul Ginzborg and Gianpasquale Santomassimo. Gibelli’s little book aimed to sketch out the contours of what he called the “Berlusconian era”, in the hope of “dismissing the character once and for all”, and exorcising the “Draquila” portrayed in Sabina Guzzanti’s 2010 documentary. However, as all these analysts saw it, the problem was not to get rid of the Berlusconi man, but of the culture of which he was the interpreter[1] . That same year, Mario Monicelli, the unforgettable director of the film I soliti ignoti (1958), responded, disillusioned, to an interview broadcast on Michele Santoro’s live program “Raiperunanotte.”[2] In it, he portrayed a subjugated country, fearful of the “revolution” it had never known. He hoped for a “great blow (bella botta) [against the system],” because, he argued, redemption would only come through sacrifice and pain.

The Italian director didn’t seem to consider the possibility, let alone the opportunity, of getting rid of Silvio Berlusconi alone. At the time, he clearly understood that it wasn’t just a question of dislodging a man from government, but of freeing himself from Berlusconism, “an eclectic ideology made up of populism, exacerbated individualism, historical revisionism, and the instrumental and identitarian use of religion.“[3] In short, to transform Italian society, which had seen the sedimentation of a “right-wing culture” that went far beyond the partisan boundaries and chronological limits of Silvio Berlusconi’s “discesa in campo” [arrival on the scene] in 1994. It was a culture that had its roots in the 1980s, those “cursed” 1980s of widespread “enrich yourself,” forced individualism “of individuals without individuality” and anti-politics. Born at the very heart of Western systems, while being a consubstantial inversion of their values, anti-politics presented itself as an anti-democratic (authoritarian and managerial) alternative to systems presented as “out of breath.”[4]

In 1993, a feature film starring Bill Murray and Andie MacDowell, entitled “Groundhog Day,” told the tale of an arrogant journalist who, stranded in a remote village in the northern USA, wakes up each morning on the day of his arrival with the knowledge that it is indeed the same day. The story – a love story, of course – that underpinned the screenplay was about Bill Murray changing his behavior in an attempt to win the heart of the beautiful Andie MacDowell. The film told us something else, however, about the new phase that was then beginning, a phase marked by what cultural theorist Mark Fisher defined as a “crushing sense of finitude and exhaustion“; “it doesn’t feel like the future,” he continued, “Or, alternatively, it doesn’t feel as if the 21st century has started yet. We remain trapped in the 20th century, just as Sapphire and Steel were incarcerated in their roadside café…”[5] . The slow weakening of the very idea of the future referred to by the philosopher Franco Berardi accompanied this process, as did its damned shadow, the destruction of the past and its memory.[6]

New Kid in Town

1992: Italy’s political system collapses. Magistrates “reveal systemic corruption” involving illegal party financing on a national scale, with Milan at its center. The city par excellence “of the optimism of the 1980s” was renamed Tangentopoli [the city of bribes].[7] In May of the same year, Mafia terror descended on Judge Giovanni Falcone, his wife, Francesca Morvillo, and his bodyguards, Rocco di Cillo, Antonio Montinaro and Vito Schifani, all murdered in Capaci; during the funeral, the politicians were whistled at by the crowd. In this climate of violence, the Chambers elect Oscar Luigi Scalfaro as the new President of the Italian Republic. In July, magistrate Paolo Borsellino and his escort are executed in Palermo. In 1993, attacks hit the cities of Florence, Rome and Milan near historic monuments, killing several people and injuring dozens more; all these events shed light on the relationship between the Italian state and organized crime.[8] As prosecutor Luca Tescaroli, interviewed by Ferruccio Pinotti in 2008, put it: “(…) The bosses explained that this was an exceptional situation, and that the ground had to be prepared for new men, whom Cosa Nostra thought they could influence, and who would therefore have obtained the mafia’s help in restoring calm.”[9]

Marcello dell’Utri was then working on the formation of a party to which Silvio Berlusconi, head of the Fininvest holding company on the verge of bankruptcy, agreed. An “interpreter of Cosa Nostra interests” within the government formed by Silvio Berlusconi in 1994, Marcello dell’Utri was sentenced in April 2018 by the Palermo Assize Court to twelve years in prison.[10] In the early 1990s, the Mani pulite (Clean Hands) judicial machine reached the heart of the political system, leading to the dissolution of Christian Democracy, in power for fifty years, and of Bettino Craxi’s Socialist Party. Added to this was the collapse of Lire under the weight of a colossal public debt, which reached 122% of GDP in 1994 (it had almost doubled between 1983 and 1993, rising from 59% to 119%), and the explosion of unemployment.[11] Meanwhile, Italy saw its first “technical” government, led by Carlo Azeglio Ciampi. But the crisis also hit the left. In February 1991, the Communist Party decided to change its name at its twentieth congress. Signaling a break in identity and reference values, it became the Democratic Party of the Left (Partito democratico della sinistra (PDS).[12] In 1992, comedian Beppe Grillo proclaimed the birth of “gentocracy”, invoking the seizure of power by people’s moods and anger. During one of his participatory shows at the Smeraldo theater in Milan, precisely where the 5-Star Movement would be founded seventeen years later, he launched his first “Vaffa…” [Go to hell…].[13] .

A veritable earthquake hit Italy between 1992 and 1994[14]. Political, institutional, economic, social and moral crises paved the way for the creation of Forza Italia (FI). In every respect, an “instant party,” “born of nothing, just the will of skillful leaders who coagulate heterogeneous forces around them, transforming them into a mass base.”[15] The latter cannot be dissociated from the figure of Silvio Berlusconi who, as a “successful entrepreneur,” plays the card of the personalization of politics, an asset in an Italy where parties have bad press. This rejection particularly affects large organizations, those of the Trente Glorieuses [the Thirty Glorious Years], with capillary networks, relying on the militant commitment of their members and representing social sectors at the heart of the political system.[16] Disaffection is certainly embodied in the scandals revealed by Tangentopoli, but it is also linked to the birth of a post-Fordist society and the changes it implies for production (rise of new information and communication technologies) and the status of employees: visible decline of the traditional working class (but not of the salaried workforce), feminization of the labor market, casualization of employment, generalization of subcontracting, weakening of solidarities, and so on.[17] This marked the beginning of a process of social fragmentation to which the post-World War II parties seemed incapable of responding. At the end of the 1980s, the Centre for the Study of Social Investment (CENSIS) painted a picture of a country that shared no “common foundation thought to be legitimate for the way we live in society;” wasn’t 12.5% of GNP the product of organized crime?[18] The historian Giampaolo Pansa then describes “an Italy that is both frightening and painful”, and which increasingly resembles that “banal and terrifying image of a gigantic landslide.”[19]

The 1980s ended with the idea that we had to start again from scratch, a dramatic nod to those who, at the beginning of the decade, were claiming a past on which to build solid constructions. Such was the case of Neapolitan comic Massimo Troisi, who in 1981 directed the film Ricomincio da tre [I begin again from three]. The political and economic crises were linked to a profound moral crisis that preceded and accompanied Operation Clean Hands, well captured in Daniele Lucchetti’s feature film Il portaborse (1991), with Nanni Moretti in the title role. Intellectuals and essayists of all stripes echoed this sentiment. Silvio Lanaro, Ernesto Galli della Loggia, Pietro Scoppola, Gian Enrico Rusconi, Norberto Bobbio and Claudio Magris, each in their own way, highlighted the fact that this crisis could lead to the “dissolution” not only of the Italian state, but also of the sense of “homeland”[20]: “If this first republic, as many observers say, is coming to an end,” writes philosopher Norberto Bobbio, “it will end badly, very badly. For those who, like me, belong to the generation that witnessed its birth, full of hope, this consideration is very bitter. From now on, I have no other desire than to get off the stage. The gestation period of the second republic, if it is to be born, will be long. Perhaps I won’t have time to see it through to the end. But since if it is born, it will be with the same men who have not only failed, but who are unaware of their own failure, it can only be born badly, very badly, as badly, very badly, as the first ended.”[21]

Silvio Berlusconi appears in this very gap. The Milanese entrepreneur was a personal friend of the socialist Bettino Craxi, whose political career and party were swept away by Tangentopoli. A member of the P2 lodge since January 26, 1978, and a fervent supporter of its “plan for democratic rebirth”, Berlusconi was an integral part of the corrupt system of the “first” Italian Republic, receiving kickbacks and favors.[22] In his famous televised self-investiture speech at the March 1994 elections, Silvio Berlusconi presented his movement as “a free organization of voters of a totally new type. Not a force born to divide, but to unite.”[23] The party bases its legitimacy precisely on the “centrality of the company.”

Forza Italia is “designed on the model of an advertising campaign,” with “no cultural heritage or ideological matrix of its own,” which seems to favor its diffuse presence and almost consolidate its validity.[24] Silvio Berlusconi calls for an end to professional politicians and all forms of social mediation. The appeal of anti-politics began to conquer the public arena, and he became its triumphant spokesman, combining the disarticulation of the social bond with absolute novelty in the Italian political field. Exacerbating the image of the leader’s sublimated relationship with his people, he proposes himself as the “only possibility of reality.”[25] In so doing, Silvio Berlusconi has already outlined the features of what some authors have called “neopopulism;”[26] in other words, an authoritarian democracy in which the direct relationship with the leader is based on “national aspirations, virtues and vices”, which he claims to embody.[27] He personifies not only his own party, but also Italian democracy; a constant in his political message. During the 2001 election campaign, he sent out a hagiographic brochure entitled An Italian History.

In 1994, Silvio Berlusconi used the analogy of “arriving on the playing field” [discesa in campo] to announce his candidacy in the forthcoming national elections. In keeping with the metaphor, the name of his party echoes the slogan fans hurl at the national team at soccer matches: Forza Italia! The choice of words was no accident: it was the fruit of an advertising operation designed to guarantee public success, as comedian Roberto Benigni mischievously argued in 1996.[28] Forza Italia, the brand, was created in the laboratory of Publitalia, part of Mediaset’s marketing department, from which it drew its political staff, notably Marcello dell’Utri. Silvio Berlusconi plays on nostalgia for the 1980s, “the most intense period of optimism” that began with the Italian soccer team’s victory in the 1982 World Cup. A national success that “seemed to exorcise the past and open the doors to a triumphant future”, a “new Italian miracle.”[29] A date that has entered the collective memory, and to which the Italian remake of Harlod Ramis’s film, entitled È già ieri [It’s already yesterday], makes a heartfelt reference. The hero (Alfredo), depressed and drunk, recalls: “When Italy won the World Cup, I too went out into the street to celebrate; it was magnificent […] why isn’t this day repeated rather than this shit…” And yet, these were years marked by private wealth and public poverty of means, infrastructure, services, a poor country inhabited by rich people[30]: “a terrible decade,” concludes Angelo d’Orsi, “marked by a global retreat of the social state, a serious loss from the point of view of the rights and living conditions of the ‘subalterns’, in an Italy plagued by widespread corruption and parties [that have] become its symbols and instruments.”[31]

On January 26, 1994, in just over nine minutes on camera, “experienced entrepreneur” Silvio Berlusconi outlined his political project. He is seated at his desk. Behind him, his family photos (the rhetorical topos of his speech) are placed in practically empty bookcases. He begins his speech by dramatizing his “renunciation” of all responsibilities in the company “he created,” in order to devote himself to public affairs; a “sacrifice” “forced” by the “lefts and communism.” His movement is then, he says, the best placed to offer Italy (“this country that I love, in which I have my hopes and my horizons”) a “credible alternative” to an “old political class, shaken by the facts and out of step with the times.” Silvio Berlusconi announced that he wanted to create a “pole of freedoms” that would attract “the best that the country has to offer, a clean, reasonable, modern” and Catholic country. The battle against the left and communism, which, by antonomasia, substituting an epithet for a name, would have brought Italy nothing but dirt, irrationality and backwardness, is central to his speech: “The orphans and nostalgics of communism […] carry with them an ideological heritage that stands in stark contrast to the demands of a public administration that intends to be liberal in politics and economics”. And he continues:

Our lefts claim to have changed. But it’s not true. Their mentality, their culture, their deepest convictions and their behavior have remained the same. They don’t believe in the market, they don’t believe in private initiative, they don’t believe in profit, they don’t believe in the individual. They don’t believe that the world can change through the free contribution of people from all walks of life. They haven’t changed. Listen to them talk, watch their state-sponsored news programs, read their press. They no longer believe in anything. They’d like to turn the country into a screaming, shouting, invective, condemning square.

Finally, Silvio Berlusconi promises “a new Italian miracle”, which a few days later, at the presentation of his movement in Rome on February 6, will become “a great, new, extraordinary Italian miracle”[32]; the transition to a “new republic” is already announced as a fait accompli. This televisual animal who, better and more than any other at the time, mastered this instrument (both financially and professionally) chose to address the viewer directly, without journalistic interruption, to be catapulted to the pinnacle of the political sphere.[33]

In January 1994, Berlusconi called on “all liberal and democratic forces” to unite under his banner. In March, he won the elections by a wide margin. In the south, he is allied with Gianfranco Fini’s Italian Social Movement (MSI), Europe’s oldest neo-fascist organization, founded just after the Second World War; in the north, with Umberto Bossi’s La lega Nord, a movement with an exacerbated identity-based regionalism that has acquired growing influence since the early 1980s. In 1991, Gad Lerner’s Profondo Nord (Deep North), a Rai3 television program, brought it into every household, giving it a national audience and a valuable platform. It was thus able to distill at leisure what some would call, not without a touch of elitism, brutal vociferations, introducing a new style to adversarial debates.[34] The Lega emerged as the real political entrepreneur of the crisis. It was born in the country’s most industrialized region, out of both “well-being and the disenchantment linked to the fear that this situation might come to an end.”[35] It had been fueled by the economic difficulties that had followed the process of European integration, and which had hit hard at the small craftsmen and entrepreneurs of the north-east, whose numbers had been steadily increasing in the 1970s and 1980s. It took root in the so-called white regions, where Christian Democracy had its traditional strongholds, presenting itself as the mouthpiece of their demands.[36] .

Silvio Berlusconi became the paladin of an “oil slick.”[37] In autumn 1993, the Milanese entrepreneur supported the candidacy of Benito Mussolini’s granddaughter, Alessandra Mussolini, for mayor of Naples (she obtained 43% of the vote), and that of Gianfranco Fin for mayor of Rome (he obtained 47% of the vote). The phrase coined by the media magnate, “If I were a Roman, I’d definitely vote for Gianfranco Fini,” made headlines in the national press[38]; the same Fini who declared in 1990: “No one can ask us to recant our fascist matrix.” At the time, he embodied an opinion widely shared within the ranks of the MSI; consider the fact that in 1990, the main historical reference for 88% of delegates to the movement’s Congress was fascism.[39] In October 1992, the MSI organized a national mobilization against corruption, playing on the proximity of the seventieth anniversary of the march on Rome and calling for an end to the “Republic of Thieves”; some 50,000 people took part, and the Repubblica headlined: “They must be stopped, and now.”[40] In January 1994, the MSI decided to found an electoral front, called Alleanza nazionale [National Alliance], intended to embody “the common house of all the Right.” In March, it entered the government, winning 13.5% of the vote and five ministries, becoming the country’s third political force; the long marginalization of the party that claimed to be Italian fascism seemed to be coming to an end, all the more surely because it was popular with those under 25.[41] The party declared itself to be “the first real political movement of the Second Republic”: “The MSI has achieved its objectives, the First Republic, against which it has fought relentlessly since 1946, has collapsed […] a new phase is beginning in which the Right must play its part […].” On April 29, 1994, the New York Times made no mistake: “After 50 years, the Fascists are back in government”; an idea confirmed some twenty years later by Gianfranco Fini himself: “After 50 years, we’re back in Italy.”[42] On January 27, 1995, in Fiuggi, a small town in the Lazio region, the MSI held its XVII congress and underwent a radical transformation. Under the strong impetus of Gianfranco Fini, it was definitively transformed into Alleanza Nazionale, a modern grouping with a more presentable name. This operation, on the hard-right side, was greatly helped by the “extremism” and what Italian newspapers called the “crassness” of the public stances taken by Lega Nord leader Umberto Bossi. The results were not long in coming, with the “new” formation gaining over 15% in the 1996 political elections.

At the Fiuggi Congress, Gianfranco Fini called for a definitive end to the “century of ideologies”, consigning fascism and anti-fascism to the history books. This declaration of intent is all the less credible given that, barely a year earlier, he was still asserting that Mussolini had been “the greatest statesman of the century.”[43] An opinion shared by the brand-new President of the Chamber of Deputies, Irene Pivetti (Lega Nord), who a few days later declared that Mussolini had put in place “the best things for women and the family”. Not to mention Council President Silvio Berlusconi, who told the Washington Post that Mussolini had “achieved good things for a time, a fact confirmed by history.”[44] The new movement’s program is entitled “Pensiamo l’Italia, il domani c’è già” [Let’s think of Italy, the future is now].[45] Gianfranco Fini’s aim was not so much to forget his neo-fascist past as to present an acceptable governmental alternative. To this end, he called for “national pacification”: “If it is indeed right to ask the Italian Right to affirm without reticence that anti-fascism was the historically essential moment for the return of the democratic values that fascism had scorned,” he writes in the “Values and principles” section of the Alleanza nazionale (AN) program, it is also fair to ask everyone to recognize that anti-fascism is not a value in itself, and that the promotion of anti-fascism as an ideology was practiced by communist countries and by the Italian Communist Party to legitimize itself during the post-war period. ” AN embraces “the values that fascism had denied”, and goes so far as to include in its “cultural heritage” the figures of the idealist philosopher Benedetto Croce and even that of the founder of the Italian Communist Party, Antonio Gramsci.

Finally, and this is undoubtedly the heart of the new program, Alleanza Nazionale intends to make a clear distinction between the Italian Right and Fascism: “The political Right is not the daughter of Fascism. The values of the Right pre-existed Fascism, they lived through it, and they have survived it. The cultural roots of the Right plunge deep into Italian history, before, during and after fascism.” And to mark the passage, Gianfranco Fini will say in Fiuggi: “I dream of a great national people’s party, capable of freeing itself from nostalgia and ideologies […] the century of fascism and anti-fascism, of communism and anti-communism is coming to an end. A new one is beginning, in which we must be guided not by ideology, but by the national interest.[46] Looking back twenty years later on the Fiuggi Congress, Gianfranco Fini would insistently reiterate the objectives behind the founding of this new Right: “… Alleanza nazionale was not a make-up operation for the MSI, […] it defined the values and program of a new Right. The ambition was to give life to a right-wing with a culture and an ability to govern, capable therefore of providing credible responses to guarantee the national interest.”[47] Initially at least, Fini’s operation seemed to succeed, so much so that in February 1995, a poll placed him as Italy’s most popular politician.[48] At the same time, the “great men” of Fascism began to emerge from the drawers, potentially functional to the “pacification” sought all the more keenly after the arrival of the neo-fascist party in government; this would be the case, in particular, of Fascist Minister of National Education Giuseppe Bottai. This led to a process of watering down Mussolini’s dictatorship, accompanied by a policy of official memory and an attempt to frame the history of fascism in Italy, which fostered the interpenetration of the conservative bourgeoisie and the neo-fascist right[49] .

Inexhaustible Seductive Power

The emergence of Silvio Berlusconi and this governmental alliance changed the face of the Right for a long time to come, and established Forza Italia as a permanent fixture on the Italian political landscape. Forza Italia and Alleanza Nazionale do not indicate clear programmatic content in their very names. Rather, they seek to present themselves as groupings that go beyond the traditional right and the neo-fascist right, blurring the boundaries. Added to this is the repeated “denial” of the existence of a specific right-wing culture, gaining in diffusion what it is supposed to lose in self-identity. This right-wing culture refers to apparently “simple” “values” such as Italian culture and “Christian tradition.”[50] A few years later, Forza Italia even went so far as to claim that the crucifix is the “basis of Italian national identity.”[51]

The exceptional ascendancy, the fascinating hold, acquired by the culture of the Berlusconian right on Italian society lies in its unprecedented ability to combine political cultures with distinct filiations: from Umberto Bossi’s Lega Nord, which combines fierce regionalism, racism and anti-State sentiment, to Alleanza nazionale, with its strong neo-fascist roots, betting on the strengthening of the State, particularly in the direction of its voters in the south of the Peninsula. In this sense, Berlusconi’s policies are akin to what the Gramscian intellectual Stuart Hall called “authoritarian populism” in 1988. Indeed, at that time, he argued, borrowing from Lenin, “absolutely dissimilar currents, absolutely heterogeneous class interests, absolutely contrary political and social endeavors merged (…) in a remarkably ‘harmonious’ way”, constituting a “historical bloc” and a new way of conceiving political space.[52] Based both on the search for “active popular consent” and on coercion (restriction and subsequent repression of collective freedoms), this new type of populism mobilized a strong cultural apparatus of ideological legitimization: end of history (Fukuyama), valorization of the individual freedoms of individuals without individuality, stigmatization of rights and in particular social rights and, last but not least, the widespread idea that there is no alternative (the famous Anglo-Saxon TINA–There Is No Alternativ). The impact was such that “someone [could argue] that it’s easier to imagine the end of the world than the end of capitalism.”[53] This is just one way of producing “consent”, on the assumption, as Michael Burawoy puts it, “that what exists is natural, inevitable and fatal”[54] . This is undoubtedly one of the most important ideological victories of capitalism, supported in its counter-offensive by its organic intellectuals. Berlusconism will also require the construction of a narrative of “origins” corresponding to all its components. Anti-communism would be its ideological cement. Indeed, its political grammar could still create illusions in a country where the Communist Party had counted over two million members and controlled the Peninsula’s main trade union. An essential part of what the political scientist Giorgio Galli called, at the end of the 1960s, the imperfect bipartite system, by the beginning of the 1990s it had become a mere shadow of its former self.[55] The major cultural overhaul carried out by this new Right has proved so successful that in January 2007, one of the think tanks close to Forza Italia, the Liberal Foundation, organized a symposium on “Berlusconism”, conferring conceptual autonomy on the “system” created by Berlusconi. Berlusconism is defined as “popular liberalism”, aimed at the middle classes, deeply Catholic and anti-communist, valuing individual freedom and market forces.

The strength acquired by this right-wing culture within Italian society can be attributed to a whole series of factors. These include, of course, the loss of any horizons for social transformation at the end of the “short twentieth century” – what some authors have defined as the “end of the post-war era”[56] ; social democracy’s wholehearted embrace of neoliberalism in the 1980s; and the fall of the Berlin Wall, which swallowed up, with its reigning bureaucracy, the last remnants of a “collectivist” experiment. British historian Eric J. Hobsbawm also refers to the “destruction of the past, or rather of the social mechanisms that link contemporaries to previous generations” as “one of the most characteristic and mysterious phenomena of the late 20e century.”[57] The “end of history” looms as the undisputed victory of capitalism, with its attendant enslavement, austerity, poverty and precariousness. The new issues and challenges besetting a society in the throes of change include a working class that is less and less perceptible, but also what Francesco Biscione has called the “repressed Republic” [“Il sommerso de la Reppublica”], i.e. the persistence of a reactionary, anti-democratic culture after the Second World War, the very breeding ground of the Berlusconi coalition.[58] All these elements are necessary to understand the apparent “victory” of this new Right, but they are not sufficient. It cannot be understood without the rift opened by the crisis on the left and the effective support of part of it for Berlusconi (or should we say mimicry?) to “wipe its slate clean and restore its power.”[59]

Silvio Berlusconi forged links with small and medium-sized businesses and with the Vatican, to which he gave guarantees both in terms of the values he defends (the family) and the interests he protects (private schools). Partly as a result, he won the national election three times, in 1994, 2001 and 2008. Each time, he strengthened his presence throughout the country, winning back former members of Bettino Craxi’s Christian Democracy and Socialist Party[60] . As far as possible, it tried to free itself from the decision-making mechanisms laid down in the Constitution; the “instant party” became the herald of a “simplified” politics, seeing parliamentarianism as an illegitimate brake, a kind of “soft dictatorship” openly hostile to representative democracy[61] ; historian Nicola Tranfaglia writes, “a system halfway between the regime of Napoleon III in France at the end of the 19e century and the more modern dictatorships of the twentieth century.”[62].

The almost total control of the television channels through which the overwhelming majority of the Italian population obtains its information, or the ad personam laws accepted under his various governments, have had the corollary of degrading or even destroying the public ethic at the very foundation of the relationship between the state and its citizens. Silvio Berlusconi has been accused of corruption, racketeering, tax evasion, extortion, abuse of office, sexual relations with minors… Marco Travaglio, editor of the newspaper Il Fatto Quotidiano, recalled this in a book published just before the March 2018 elections and entitled B. come Basta (B. comme ça suffit!): “No rehabilitation,” he wrote, “will ever be able to erase the indisputable facts that make B., in the following order: an inveterate fraudster; the protagonist of a mutual aid pact stipulated in 1974 with the leaders of Cosa Nostra; the financial backer of the mafias for eighteen years […the accomplice of a man convicted of external assistance in a Mafia association; the probable port of arrival for negotiations between the State and the Mafia; a corrupter of senators and witnesses; a secret payer for [Bettino] Craxi, head of a group that suborned judges, financiers and politicians, bought sentences and falsified balance sheets, accumulated mountains of black funds and stole Italy’s leading press group from a competitor with bribes; entered politics in 1994 to avoid prison and bankruptcy….”[63]

The Slow Demise of the “Near-immortal”

In July 2012, a poll dedicated to “the events that have changed Italy the most over the last thirty years” ranked Silvio Berlusconi third, in order of importance, after the economic crisis and the introduction of the euro in 1996, but ahead of Tangentopoli, terrorism and the end of the same Berlusconi’s government, “pushed out” in November 2011 under pressure from the financial markets and European institutions, worrying about the ever-increasing Italian public debt (102.4% of GDP in 2008, 112.5% in 2009); In 2010, it reached its highest level since 1997, at 115.4% of GDP.[64] As historian Antonio Gibelli noted in 2010[65], the Cavaliere has truly “entered the history books.” He produced the most striking innovations in Italian society’s relationship with politics, creating and personifying the new “imaginary” of a nation where the informal economy plays a structural role; where individualism is the rule; where, better still, the bonds of basic solidarity are fading away; where the assumption of responsibility is replaced by the lure of disempowered participation; where “political passion” has given way to an atomized society, reduced to seeing only the glittering dancers on national TV, and hearing only vulgarity, “histrionics” and insults presented as a guarantee of “truth” against the “falsehoods” and hypocrisy of “political correctness.” Because Silvio Berlusconi didn’t use television, “he [was] television” and inhabited it not only with his body, but also with his values and styles, setting up what some authors have called a veritable videocracy; spectacle politics, which no longer distinguishes between the political sphere and the media sphere at the root of infotainment, where the “political animal” plays the role of an actor in a shadow play that seeks to feed passion and foster, to paraphrase Antonio Gramsci, a “sentimental connection” between the staged political figure and his or her audience.[66] The extraordinary seductive power of Berlusconism has long led the Italian population to perceive as natural the dissolution of the essential principles on which its relationship with civil society had hitherto rested.[67]

Since his forced departure from the government at 9:42 pm on November 12, 2011, to the booing and Hallelujahs of the public, Silvio Berlusconi’s political decline seemed indisputable. The shift in the balance of power within the Right in the elections of March 2018 and September 2022 has confirmed this. Over the last five years, from all sides, the death of the “almost immortal” of the “most vivacious politician among those whom history has killed several times” has been announced[68] : “The charm, the great spell that deceived Italians for almost twenty years is now broken. Silvio Berlusconi is no longer able to bewitch the country […]”, writes Claudio Tito in the columns of the daily La Repubblica.[69] The spell no longer works for the man who presented himself in 1994 as a “miracle-working entrepreneur.” Paolo Sorrentino’s film Loro [Silvio and the others], dedicated to the cavaliere‘s final run between 2007 and 2009 and released in cinemas just a few weeks after the national consultation in March 2018, portrays this decline: “We’re crying even when he’s still making us laugh,” says Santino Recchia, alter ego in Sorrentino’s fiction of Culture Minister Sandro Bondi. Over the years, he’s given us two things we weren’t able to get on our own. Economic strength and enthusiasm. But that’s no longer enough. The personal party is stuck precisely on the figure of this Silvio Berlusconi, portrayed by right-wing journalist Marcello Veneziani, as the planisphere of this stupid Ventennio and its ultimate consequences” who “bears the scars, aggravated by the pre-printed smile.”[70]

The attack on Silvio Berlusconi’s physical characteristics is not an excess of youthism applied to the politics of a country that has seen the rise of the forty-something Matteo Salvini, and today of the young Giorgia Meloni, but is rather part of what had been at the heart of the Berlusconi system: his pervasive physicality, the care taken in representing the man who, more and better than any other, had played on and of his image, the “greatest phenomenon of the century” according to Beppe Grillo.[71] Ironically, the anthem composed in 2002 for Silvio Berlusconi (Meno male che Silvio c’è [Fortunately Silvio exists]), used during the 2008 campaign, became a hit and among the most downloaded tracks on Spotify on the eve of the March 2018 elections.[72] Yet, nicknamed “Le revoici” (Rieccolo), a sort of infernal jack-in-the-box, the vintage Berlusconi, reassuring “trinket” once again posed as one of the arbiters of the March 2018 national consultation.[73] During Mario Monti’s governmental experience, when he had only just been ousted from power, had we not already heard again the saying in vogue after the Second World War, “We were better when it was worse” [Si stava meglio, quando si stava peggio], accompanied by the idea that finally “Berlusconi was a nice man”[74] .

The Caiman seemed to rise from the ashes many times, including in early May 2023, at the Forza Italia Congress, despite his frozen, pale face resembling the carnival masks that had flourished in the anti-Berlusconi Italy of the early 2000s; effigies brandished by demonstrators on No-B[erlusconi] Day on December 5, 2009 to demand his resignation.[75] At the heart of the right-wing constellation, he recently appeared to be the one who could calm the ardors of Matteo Salvini and Giorgia Meloni.[76] A moderate Berlusconi as a token of moral and political virginity. In 2018, Forza Italia posters read, alongside “Berlusconi President,” “Honesty, experience, wisdom,” a slogan that grated on those who still had in mind the heavy criminal record of the Forza Italia leader, defined by the Milan court as having “a natural penchant for crime.” Silvio Berlusconi was also barred from standing in the March 2018 elections, having been sentenced to more than two years’ imprisonment (the so-called “Severino Law” of 2012).

Since 2018, all over Europe, a “reloaded” Silvio Berlusconi seemed to be able to ward off the specter of “populism”.[77] Eugenio Scalfari, founder of the daily La Repubblica, who had spearheaded the battle against Berlusconi’s governments (think of the ten embarrassing questions asked of the then President of the Council in 2009 about his relations with underage girls[78] ), launched an appeal to vote for Forza Italia. From Angela Merkel to Jean-Claude Juncker, not forgetting Martin Schultz, the Socialist whom he had called a Kapo in the European Parliament in 2014, all encouraged this outcome. Even Bill Emmott, the former editor of The Economist, who in 2001 devoted his front page to Berlusconi with the headline “Why Berlusconi is unfit to lead Italy”, presented him in January 2018 as the potential savior of the peninsula.[79] And workerist Toni Negri sententiously announced in Vanity Fair that he “regrets the absurd way in which [Silvio Berlusconi] has been treated. […] Berlusconi was condemned first of all by the press, by his opponents and by the judges”, a whitewashing of the “spiritual father of the right” by one of the “heroes” of the far left[80] .

And yet, the overwhelming majority of Italian politicians wanted to see the demise of Berlusconi, whom John Hooper, a journalist with The Economist, classed as one of the “Dirty Dozen” who ruined Italy along with Benito Mussolini and Bettino Craxi.[81] And it was on the right that the need for him to hand over was expressed most compellingly: And as Marcello Veneziani on September 28, 2018, in a sort of vitriolic funeral oration”

In our eyes, you have had the merit of bringing together the backbench of the right and bringing them into government – moderates and populists, secessionists and nationalists – defeating the left and the powers that supported it. You were our most formidable electoral machine. You succeeded in founding from nothing a party that was the most voted for several years; you brought to power the lepers of the Italian Social Movement and the rustics of the Lega. You had the support of the people and the hostility of the palaces. […] You were the main driving force behind the success of the center-right, but then you became the major cause of its ruin […]. [82]

Silvio Berlusconi’s goal was to unify the right by “clearing its name” and turning it into a force for government, a plan he had been toying with since at least the late 1970s, when he joined the P2 Lodge and financed a spin-off of the Italian Social Movement, called Democrazia nazionale, to support the Christian Democracy in parliament.[83] In 2012, he again supported the creation of Fratelli d’Italia, whose triumvirate (Ignazio La Russa, Giorgia Meloni and Guido Crosetto), his former government team, remained loyal to him, giving the new party 750,000 euros[84] . Since the 1990s, he has made Italy the laboratory of a new right-wing constellation with a powerful capacity for attraction, based on a “space of common sense”, which Guido Caldiron has rendered by the notion of “plural right”[85] . This is defined by the “porous borders” between the right and the far right, and by the increasingly perceptible “dilation” of the far right’s space for political and cultural intervention.[86]

This plural right has succeeded in placing its flagship themes at the center of debate, of which the rejection of immigration, symbolized at government level in 2002 by the Bossi-Fini law, the rejection of the welfare state and the stigmatization of the poor, are undoubtedly the unifying elements par excellence.[87] But it has also managed to seize upon what the Argentine political scientist Ernesto Laclau has called empty signifiers, investing them with its own grammar and turning them into a “formidable weapon of ideological hegemony”, including freedom, equality and universalism.

Silvio Berlusconi’s last message to his party and voters last May reaffirmed the existence of a “center-right,” firmly anchored in “liberal and Christian values.” A few years ago, Tariq Ali and Alain Deneault suggested “adopting and disseminating the notion of the extreme center” to “reveal the extent to which, under the guise of moderation and ‘common sense,’ its proponents are implementing a project whose means and ends are in fact ‘extreme’, in other words brutal, extravagant, even insane.”[88] A study excerpted by the New York Times even points out that “centrists are the least supportive of democracy, the least committed to democratic institutions and the most in favor of an authoritarian outcome”.[89] Ultimately, the Forza Italia leader’s political epilogue is not all that far removed from the finale dedicated to him by filmmaker Nanni Moretti in 2006, the anguished vision of a megalomaniac autocrat unable to relinquish power: judges assassinated; palaces and courts in flames; a country in the grip of a coup d’état. The outcome of Berlusconi’s parable, leading to the installation in power of “Mussolini’s little children”, leaves us wondering….

This article was originally published in the French journal AOC. The translation was done using DeepL.

Notes:

[1] Gabriele Turi, “Quella cultura che sopravvivrà al suo interprete”, la Repubblica, October 16, 2010.

[2] Rai per una notte, March 25, 2010.

[3] Gabriele Turi, “Quella cultura che sopravvivrà al suo interprete”, la Repubblica, October 16, 2010.

[4] Carlo Donolo, “Del buon uso dell’antipolitica: i confini mobili del politico nei regimi democratici”, Meridiana, 2001.

[5] Mark Fisher, Ghost of my life. Writing on depression, hauntology and Lost futures, Winchester&Washington, Zero Books, 2014, p. 8.

[6] Franco Berardi (Bifo), Dopo il futuro: dal Futurismo al Cyberpunk. L’esaurimento della Modernità, Rome, DeriveApprodi, 2013.

[7] Guido Crainz, “Italy’s political system since 1989”, Journal of Modern Italian Studies, 2015, N°20, p. 177.

[8] Piero Craveri, “Régimes politiques, État et nation en Italie”, Vingtième siècle. Revue d’histoire, N°100, 2008, p. 87.

[9] Ferruccio Pinotti, Luca Tescaroli, Colletti sporchi, Milan, BUR, 2008; also quoted by Nicola Tranfaglia, Populismo autoritario. Autobiografia di una nazione, Milan, Baldini&Castoldi, 2010, p. 81.

[10] Giuseppe Lo Bianco, Sandra Rizza, “Condannati Stato e mafia: 12 anni a Dell’Utri e Mori”, il Fatto Quotidiano, April 21, 2018.

[11] Nicola Tranfaglia, Anatomia dell’Italia repubblicana 1943-2009, Florence, Passigli Editore, 2010; Id. in Vent’anni con Berlusconi (1993-2013). L’estinzione della sinistra, Milan, Garzanti, 2009, p. 15.

[12] Adele Sarno, “Stragi, il “papello” e tangentopoli. 1992, l’anno che cambiò l’Italia”, la Repubblica, October 18, 2011. Marco Berlinguer, “Qualcosa rinascerà ma sarà diverso. Intervista a Rossana Rossanda”, November 18, 2012 (http://web.rifondazione.it/).

[13] Leonardo Bianchi, La gente. Viaggio nell’Italia del risentimento, Rome, Minimum Fax, 2017.

[14] Rosario Forlenza, Bjorn Thomassen, Italian Modernities: Competing Narratives of Nationhood, Basingstoke, Palgrave MacMillan, 2016, p. 249.

[15] Doriano Pela, “L’identità politica tra pubblico e privato”, in Paolo Sorcinelli, Daniela Calanca (eds.), Identikit del Novecento: conflitti , trasformazioni sociali, stili di vita, Rome, Donzelli, 2004, p. 266 (quoted also in Marco Revelli, Populismo 2.0,Turin, Einaudi, 2017, p. 123).

[16] Marco Revelli, Finale di partito, Turin, Einaudi, 2013, p. XI.

[17] Luciano Gallino, La lotta di classe dopo la lotta di classe. Intervista a cura di Paola Borgna, Bari, Laterza, 2012.

[18] Guido Crainz, Autobiografia di una repubblica. Le radici dell’Italia attuale, Rome, Donzelli, 2009, p. 5; Id. in Il paese reale dall’assassinio di Moro all’Italia di oggi, Rome, Donzelli, 2012, p. 225 ff.

[19] Giampaolo Pansa, I bugiardi, Milan, Sperling&Kupfer, 1992, p. 309.

[20] Claudio Magris, “Né disgregazione, né assuefazione”, Corriere della Sera, November 2, 1993; Gian Enrico Rusconi, Se cessiamo di essere una nazione, Bologna, Il Mulino, 1993; Silvio Lanaro, Storia dell’Italia repubblicana. Dalla fine della guerra agli anni novanta, Venice, Marsilia, 1992; Pietro Scoppola, La Repubblica dei partiti; profilo storico della democrazia in Italia (1945-1990), Bologna, Il Mulino, 1991; Ernesto Galli della Loggia, La morte della patria. La crisi dell’idea di nazione tra Resistenza, antifascismo e Repubblica, Rome, Laterza, 1996; see also Guido Grainz, Il paese reale, op. cit. p. 227.

[21] Dalla stessa leva. Lettere (1942-1999). Carteggio fra Norberto Bobbio e Eugenio Garin, Turin, Aragno, 2011; quoted in Guido Crainz, Il paese reale, p. 235.

[22] Perry Anderson, “An entire order converted into what it was intended to end”, London Review of Books, vol. 31, N°4, 26 February 2009.

[23] S. Berlusconi, “Il discorso della discesa in campo. Per il mio Paese”, January 26 1994 (http://www.cini92.altervista.org/discorsoberlusconi.html).

[24] Giovanni Valentini, “Forza Italia Congresso virtuale”, la Repubblica, April 15, 1998; Doriano Pela, “L’identità politica tra pubblico e privato”, in Paolo Sorcinelli, Daniela Calanca (eds.), Identikit del Novecento, pp. 266-67.

[25] M. Revelli, Populismo 2.0, p. 123; as well as G. Turi, La cultura delle destre. Alla ricerca dell’egemonia culturale, Turin, Bollati Boringhieri, 2013, p. 60; Carlo Donolo, “Del buon uso dell’antipolitica”, art. cit.

[26] S. Luciano, “Basta con i politici di mestiere”, La Stampa, 9 febbraio 1993.

[27] Ilvo Diamanti, Gramsci, Manzoni e mia suocera. Quando gli esperti sbagliano previsioni politiche, Bologna, Il Mulino, 2012.

[28] Tutto Benigni, 1996.

[29] Guido Crainz, Autobiografia, p. 149.

[30] Gianpasquale Santomassimo, “Origini e culture del berlusconismo. Eredità degli anni Ottanta”, Italia contemporanea, N°260, September 2010, p. 385.

[31] Angelo d’Orsi, “Aridatece er puzzone? Riflessioni politiche di fine anno”, MicroMega, December 31, 2018.

[32] S. Berlusconi, “Il discorso della discesa in campo. Per il mio Paese”, January 26 1994 (http://www.cini92.altervista.org/discorsoberlusconi.html).

[33] Mauro Calise, Fuorigioco. La sinistra contro i suoi leader, Bari, Laterza, 2013.

[34] Simona Colarizi, Marco Gervasoni, La cruna dell’ago. Craxi, il partito socialista e la crisi della Repubblica, Bari, Laterza, 2005, pp. 259-260.

[35] Ilvo Diamanti, “La Lega imprenditore politico della crisi”, Meridiana, 1993, p. 16.

[36] Dwayne Woods, “A critical analysis of the Northern League’s ideographical profiling”, Journal of Political Ideologies, N°15, 2010, p. 214.

[37] Giovanni Valenti, “Un ‘Cavaliere nero’ per gli orfani del regime”, la Repubblica, November 24 1993.

[38] Ibid.

[39] Tom Gallagher, “Exit from the ghetto: the Italian far right in the 1990s”, in Paul Hainsworth (ed.), Politics of the Extreme Right: from the Margins to the Mainstream, London, Bloomsbury, 2016 [2000], p. 66.

[40] Orazio La Rocca, “Camicie nere in piazza. Il MSI torna a sfilare”, la Repubblica, October 18, 1992; see also Guido Crainz, Il paese reale, p. 288; R. Zuccolini, “MSI, manifestazione coi guanti”, Corriere della Sera, October 18, 1992.

[41] Tom Gallagher, “Exit from the ghetto”, art.cit. p. 74.

[42] Aldo di Lello, “Pensare in grande e sognare il futuro”, Il Secolo d’Italia, January 27, 2015.

[43] “Intervista a Gianfranco Fini”, La Stampa, April 1er 1994; on this subject, see F. Focardi, La guerra della memoria. La Resistenza nel dibattito politico italiano dal 1945 ad oggi, Bari, Laterza, 2005. See also S. Pivato, Vuoti di memoria. Usi e abusi della storia nella vita pubblica italiana, Bari, Laterza, 2007.

[44] “Il Fascismo tutelò la famiglia”, La Repubblica, April 22, 1994;

[45] The program is published as a supplement to the Il Secolo d’Italia newspaper.

[46] Nicola Tranfaglia, Populismo autoritario, p. 16.

[47] Aldo di Lello, “Pensare in grande e sognare il futuro”, Il Secolo d’Italia, January 27, 2015.

[48] Corriere della Sera, February 27, 1995; quoted in David Art, “Memory and Politics in Western Europe”, in Uwe Backes, Patrick Moreau, The Extreme Right in Europe: Trends and Perspectives, Göttingen,Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 2011, p. 378.

[49] Gabriele Turi, La cultura delle destre, p. 25.

[50] Ibid. p. 55 and p. 77.

[51] Ibid, p. 96.

[52] Lenin, “Letter from afar”, March 1, 1917 (published March 20-21, 1917 in Pravda). Quoted in S. Hall, “The Great Moving Right Show”, January 1979, p. 14. See also Id, “Brave New World”, Marxism Today, October 1988, p. 24 (French translation: Le populisme autoritaire: puissance de la droite et impuissance de la gauche au temps du thatchérisme et du blairisme, Paris, Amsterdam, 2008, p. 31-50 and p. 83-100).

[53] Frederic Jameson, “Future City“, New Left Review, N°21, May-June 2003, p. 76.

[54] Michael Burawoy, Manufacturing Consent: Changes in the Labor Process Under Monopoly Capitalism, Chicago University Press, Chicago, 1979, p. 13 (French translation: Produire le consentement, Montreuil, La Ville Brûle, 2015).

[55] Giorgio Galli, Il bipartismo imperfetto, Bologna, Il Mulino, 1967.

[56] Stefano Levi Della Torre, “Fine del dopoguerra e sintomi antisemitici”, Rivista di storia contemporanea, N°4, 1984, pp. 437-555.

[57] Eric J. Hobsbawm, The Age of Extremes. Histoire du court 20e siècle, Brussels, Complexe, 1994, p. 21.

[58] Francesco Biscione, Il sommerso della Repubblica. La democrazia italiana e la crisi dell’antifascismo, Turin, Bollati-Boringhieri, 2003.

[59] Perry Anderson, “An invertebrate left. Italy’s Squandered Heritage”, London Review of Books, vol. 13, N°5, March 2009. An abridged version, translated by myself, was published in Contretemps, http://www.contretemps.eu/interventions/gauche-invertebree-lheritage-dilapide-gauche-italienne.

[60] Nicola Tranfaglia, Populismo autoritario, p. 83.

[61] Marco Revelli, Populismo 2.0, Turin, Einaudi, 2017, p. 127.

[62] Nicola Tranfaglia, Vent’anni con Berlusconi (1993-2013). L’estinzione della sinistra, Milan, Garzanti, 2009, p. 19.

[63] Marco Travaglio, “Chi riabilita chi”, Il Fatto Quotidiano, May 13, 2018.

[64]Banca d’Italia, Istat: http://www.irpef.info/testi/debito.html.; http://www.demos.it/a00739.php; see also Ilvo Diamanti, “Peggio di Berlusconi nessuno mai”. Un Italiano su due boccia il ritorno”, la Repubblica, July 16, 2012; Timothy F. Geithner, Stress test. Reflections on Financial Crisis, London, Random House Business Book, 2014; also quoted in Joseph Confavreux, Ludovic Lamant, “La crise italienne est aussi celle de l’Europe”, Mediapart.fr, May 28, 2018.

[65] A. Gibelli, Berlusconi passato alla storia.

[66] Antonio Gramsci, Quaderni del Carcere, vol. II Quaderni 6-11, Turin, Einaudi, 1977, pp. 1505-1506 (§67) (French version, Antonio Gramsci, Cahiers de prison. Cahiers 10, 11, 12, 13, Paris, Gallimard, 1978, pp. 299-300).

[67] Gianpasquale Santomassimo, “Marxismo e storia dal solido al liquido”, Passato e Presente, N°72, 2007, p. 138.

[68] Mauro Calise, Fuorigioco. La sinistra contro i suoi leader, Bari, Laterza, 2013; Bruno Ravaz, “Le populisme de Berlusconi ou les recettes de la popularité durable”, Pouvoirs, N°4, 2009, p. 151.

[69] Claudio Tito, “Il Cavaliere stanco tra manie e déjà vu“, la Repubblica, March 3, 2018.

[70] Marcello Veneziani, “82 anni, per i suoi nemici 41bis”, marcelloveneziani.com, September 2018.

[71] Nicola Mirenzi, “Intervista a Belpoliti. Il corpo di Luigi di Maio”, RollingStone, 13 febbraio 2018; Beppe Grillo, “L’affaire Parmalat ou le crépuscule de l’Italie”, Courrier international, March 31, 2004.

[72] Mario Ajello, “Berlusconi diventa una “hit”, “Meno male che Silvio c’è” tra i brani più scaricati da Spotify”, Il Messaggero, March 3, 2018.

[73] Philippe Martinat, “Elections in Italy: ‘When you look at this campaign, you see a country in decline'”, Le Parisien, February 28, 2018

[74] Angelo d’Orsi, “Aridatece er puzzone? Riflessioni politiche di fine anno”, MicroMega, December 31, 2018.

[75] Franco Cordero, Le strane regole del Signor B, Milan, Garzanti, 2003; Id, Nere lune d’Italia, Milan, Garzanti, 2004.

The nickname was also used in Nanni Moretti’s film of the same name, released in 2006.

[76] Michael Braun, “La metamorfosi dei Cinquestelle da Grillo a Di Maio”, Internazionale, February 23, 2018.

[77] Massimo Giannini, “L’eterno ritorno”, art. cit.

[78] Giuseppe D’Avanzo, “Incoerenza di un caso politico: Dieci domande a Silvio Berlusconi”, la Repubblica, May 15 2009.

[79] Massimo Giannini, “Berlusconi ha finito i miracoli”, la Repubblica, March 4, 2018; Bill Emmott, “The Bunga-Bunga Party returns to Italy”, project-syndicate.com, January 4, 2018.

[80] Francesco Oggiano, “Toni Negri: sinistra polverizzata, ci salveranno i poteri forti”, Vanity Fair, January 29, 2018; Massimo Giannini, “L’eterno ritorno”, art. cit.; Marco Travaglio, “Bollito misto”, Il Fatto Quotidiano, February 28, 2018.

[81] John Hooper, “12 people who ruined Italy”, Politico.eu, May 25, 2018.

[82] Marcello Veneziani, “82 anni, per i suoi nemici 41bis”, art. cit.

[83] Nicola Tranfaglia, Vent’anni con Berlusconi, p. 72.

[84] Andrea Palladino, “La nascita di Fratelli d’Italia”, MicroMega, April 24, 2023.

[85] Guido Caldiron, La destra plurale. Dalla preferenza nazionale alla tolleranza zero, Rome, Manifestolibri, 2001, p. 9. See chapter 1.

[86] E. Traverso, “L’islamophobie” art. cit.

[87] Dwayne Woods, “A critical analysis of the Northern League’s ideographical profiling”, Journal of Political Ideologies, N°15, 2010, pp. 212-13

[88] Tariq Ali, The Extreme Centre, London, Verso, 2015; Alain Deneault, La politique de l’extrême center, Montreal, Lux, 2016; Grégory Salle, “A propos de l”extrême center'”, Contretemps, July 13, 2017.

[89] David Adler, “Centrists are the most hostile to democracy not Extremists,” New York Time, May 23, 2018; see also Id. in The Centrist Paradox. Political Correlates of the Democratic Disconnect, August 4, 2018 (ssrn.com).

The tragic death of Nahel in Nanterre highlighted the tensions that are still very high in France’s working-class neighborhoods, which go beyond police violence and are linked to the injustices and discrimination experienced on a daily basis. They require a short- and long-term political response.

The tragic death of Nahel in Nanterre highlighted the tensions that are still very high in France’s working-class neighborhoods, which go beyond police violence and are linked to the injustices and discrimination experienced on a daily basis. They require a short- and long-term political response.

The Soviet Union’s demise and the end of the Cold War almost put an end to the ‘campism’ that characterized until then much of the international left and the workers movement. The term ‘campism’ was coined during the Cold War to designate a systematic alignment among this range of forces behind either Washington or Moscow. While there still exist political groups systematically aligned behind Cuba, or even behind Putin’s Russia in the case of die-hard Stalinists whose attachment to the USSR morphed into attachment to anything Russian, a new phenomenon emerged, that of

The Soviet Union’s demise and the end of the Cold War almost put an end to the ‘campism’ that characterized until then much of the international left and the workers movement. The term ‘campism’ was coined during the Cold War to designate a systematic alignment among this range of forces behind either Washington or Moscow. While there still exist political groups systematically aligned behind Cuba, or even behind Putin’s Russia in the case of die-hard Stalinists whose attachment to the USSR morphed into attachment to anything Russian, a new phenomenon emerged, that of

[John Feffer was interviewed by email by Stephen R. Shalom of the New Politics editorial board.]

[John Feffer was interviewed by email by Stephen R. Shalom of the New Politics editorial board.]

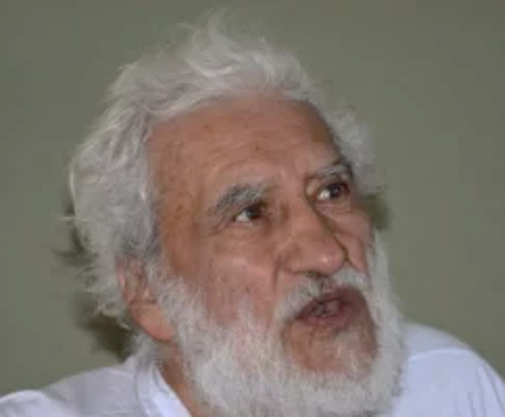

Blanco, the Peruvian revolutionary is dead. I met him once back in 1996 when my wife Sherry and I were living in Mexico City. It was an experience of magical realism.

Blanco, the Peruvian revolutionary is dead. I met him once back in 1996 when my wife Sherry and I were living in Mexico City. It was an experience of magical realism.

Silvio Berlusconi has died at the age of 86. In early May, he spoke from his hospital room at the Forza Italia Congress, recalling “his” glorious years, when he fought to “save democracy and freedom” from “communism.” Retracing the history of his party, from its entry into politics in 1994, he said that Forza Italia was the backbone of Giorgia Meloni’s government. He will undoubtedly leave a lasting mark.

Silvio Berlusconi has died at the age of 86. In early May, he spoke from his hospital room at the Forza Italia Congress, recalling “his” glorious years, when he fought to “save democracy and freedom” from “communism.” Retracing the history of his party, from its entry into politics in 1994, he said that Forza Italia was the backbone of Giorgia Meloni’s government. He will undoubtedly leave a lasting mark.

Our recent coverage of

Our recent coverage of

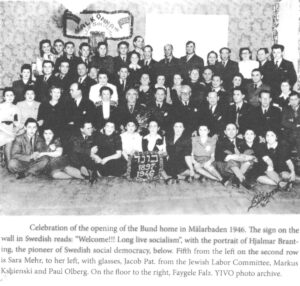

The views of Left and Right differ regarding the study of history. For the Right it is largely an exercise in building identity and loyalty, an exploration of what makes one’s nation and race, and therefore one’s self, special. For the Left it’s generally a quest for truth, and lessons from the past no matter how unpleasant they may be, in order to achieve justice. This is clear to anyone paying attention to current debates about the legacy of slavery, colonization, and the ongoing reactionary hysterics surrounding “Critical Race Theory.” Now we are seeing the opening of a new front in the conflict. A battle over old ground long held to be of prime strategic importance to the Right. The history of Socialism.

The views of Left and Right differ regarding the study of history. For the Right it is largely an exercise in building identity and loyalty, an exploration of what makes one’s nation and race, and therefore one’s self, special. For the Left it’s generally a quest for truth, and lessons from the past no matter how unpleasant they may be, in order to achieve justice. This is clear to anyone paying attention to current debates about the legacy of slavery, colonization, and the ongoing reactionary hysterics surrounding “Critical Race Theory.” Now we are seeing the opening of a new front in the conflict. A battle over old ground long held to be of prime strategic importance to the Right. The history of Socialism.

One of the paradoxes of the war in Ukraine is that some of us have discovered the existence of an active left and a critical and creative thinking in Ukraine that we (including the author of these lines) have ignored for too many years. Amongst our revelations, Commons, Journal of Social Criticism, is certainly one of the most important and productive places for us to understand the situation in Ukraine — and in the world. It publishes its articles in Ukrainian, English, and Russian. Today Commons is a reference website for critical thinking on the European left. While the site deals with issues specific to Ukraine, it is open to the world. One of its recent initiatives is the “Dialogues of the peripheries”, the objective being that “resistance to the capitalist system should be a way to find alternative solutions for all countries of the global periphery. To this end, we are initiating a common independent dialogue with activists from different regions, from Latin America to East Asia.” I recently had a conversation with the editorial board of Commons.

One of the paradoxes of the war in Ukraine is that some of us have discovered the existence of an active left and a critical and creative thinking in Ukraine that we (including the author of these lines) have ignored for too many years. Amongst our revelations, Commons, Journal of Social Criticism, is certainly one of the most important and productive places for us to understand the situation in Ukraine — and in the world. It publishes its articles in Ukrainian, English, and Russian. Today Commons is a reference website for critical thinking on the European left. While the site deals with issues specific to Ukraine, it is open to the world. One of its recent initiatives is the “Dialogues of the peripheries”, the objective being that “resistance to the capitalist system should be a way to find alternative solutions for all countries of the global periphery. To this end, we are initiating a common independent dialogue with activists from different regions, from Latin America to East Asia.” I recently had a conversation with the editorial board of Commons.

Traveling anywhere in Turkey in recent weeks one is accosted by reminders of an election scheduled for May 14. The visages of smiling political leaders adorn billboards and banners everywhere. The most ubiquitous image, of course, is that of President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, whose campaign motto is Doğru Zaman, Doğru Adam: “Right Time, Right Man.”

Traveling anywhere in Turkey in recent weeks one is accosted by reminders of an election scheduled for May 14. The visages of smiling political leaders adorn billboards and banners everywhere. The most ubiquitous image, of course, is that of President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, whose campaign motto is Doğru Zaman, Doğru Adam: “Right Time, Right Man.”

In the face of the nightmare that Sudan is going through these days, we have a dream: the dream that the infighting between military factions in a country whose history has witnessed an alternation of revolutionary surges and military coups, with the latter periodically suppressing the achievements of the first—that the infighting between the regular armed forces led by Abdel Fattah al-Burhan and the Rapid Support Forces, led by Muhammad Hamdan Dagalo, may have the same effect that wars have had on some of the major revolutions of the modern era. It is well-known indeed that major revolutionary uprisings in modern history did occur against the background of a defeat of their country’s armed forces: from the Paris Commune in 1871 to the first Russian revolution in 1905, to the second in 1917, to the German revolution in 1918, etc.

In the face of the nightmare that Sudan is going through these days, we have a dream: the dream that the infighting between military factions in a country whose history has witnessed an alternation of revolutionary surges and military coups, with the latter periodically suppressing the achievements of the first—that the infighting between the regular armed forces led by Abdel Fattah al-Burhan and the Rapid Support Forces, led by Muhammad Hamdan Dagalo, may have the same effect that wars have had on some of the major revolutions of the modern era. It is well-known indeed that major revolutionary uprisings in modern history did occur against the background of a defeat of their country’s armed forces: from the Paris Commune in 1871 to the first Russian revolution in 1905, to the second in 1917, to the German revolution in 1918, etc.