The Russian war on Ukraine is the result of the imperialist ideology and the economic and geopolitical objectives of Vladimir Putin and the Russian state. Russia is, as it has long been, an imperial power seeking to eliminate Ukraine as an independent state and even to erase the Ukrainians as a people. The roots of this Russian aggression are to be found in the Tsarist and more particularly in the Soviet regime, imperial ambitions now embodied in Putin and his regime. The purpose of this article is to explain the origin and evolution of Russian imperialism and to discuss the war on Ukraine in that light of that understanding. I believe that this history is necessary in order to understand Russia and its relationship to Eastern Europe and in particular to Ukraine.

The Russian war on Ukraine is the result of the imperialist ideology and the economic and geopolitical objectives of Vladimir Putin and the Russian state. Russia is, as it has long been, an imperial power seeking to eliminate Ukraine as an independent state and even to erase the Ukrainians as a people. The roots of this Russian aggression are to be found in the Tsarist and more particularly in the Soviet regime, imperial ambitions now embodied in Putin and his regime. The purpose of this article is to explain the origin and evolution of Russian imperialism and to discuss the war on Ukraine in that light of that understanding. I believe that this history is necessary in order to understand Russia and its relationship to Eastern Europe and in particular to Ukraine.

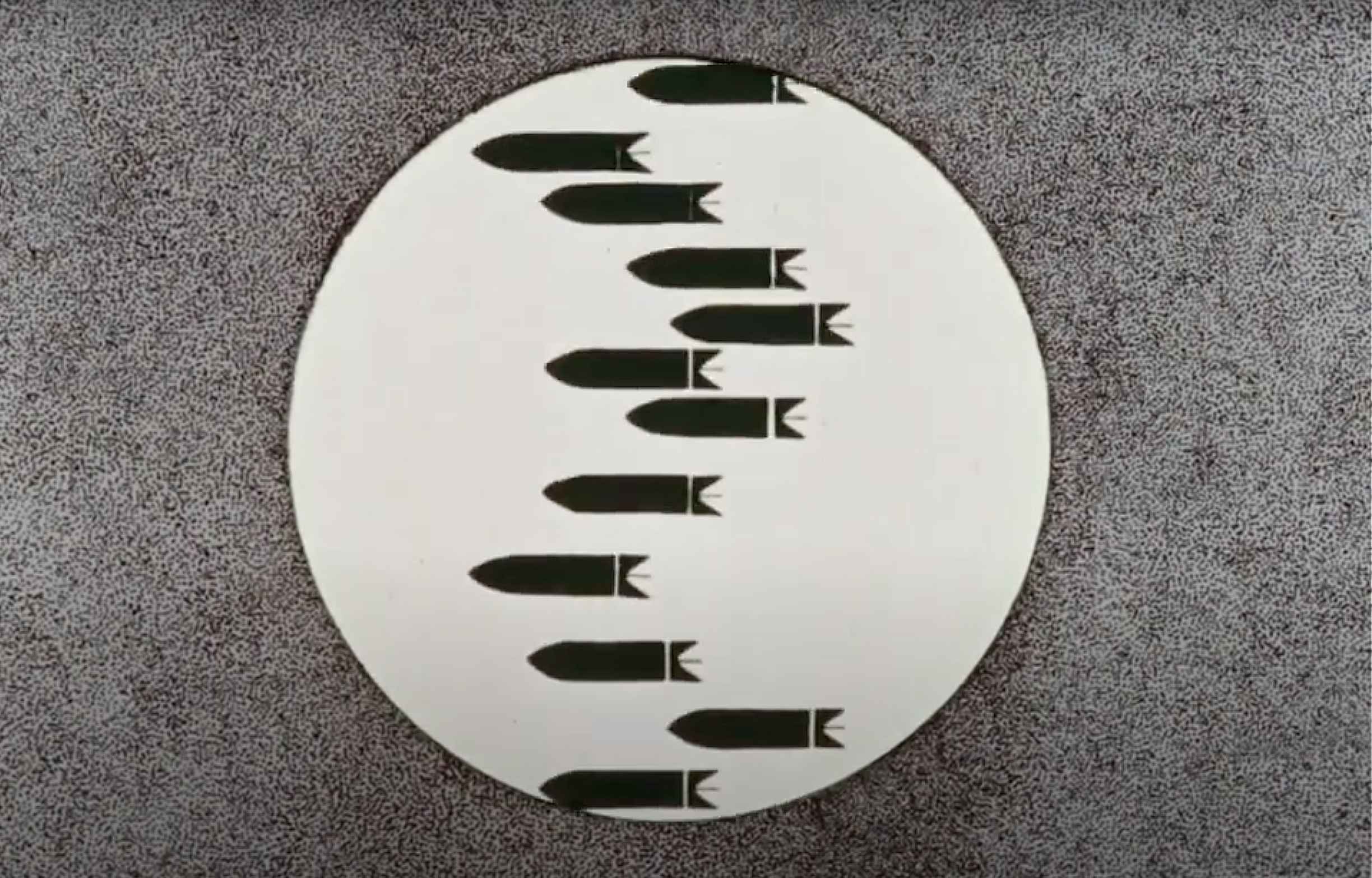

Let us first remember where we are now. Russia has made a full-scale war on Ukraine now for an entire year, a war that has brought incalculable destruction and suffering to Ukraine. The war has taken the lives of an estimated 100,000 Ukrainian soldiers. Russia has killed thousands of Ukrainian civilians, forced millions to flee abroad, and it has carried out a variety of war crimes and crimes against humanity—bombing residences, hospitals, schools, and kidnapping children and changing their nationality, crimes that taken together can be interpreted as an ethnocidal or genocidal war. The war threatens other nations in Europe; there is fear that Moldova may be Vladimir Putin’s next target. It has drawn into it as purveyors of arms to Ukraine or Russia other countries around the world; it has disrupted grain shipments to the Middle East and Africa and contributed to hunger there; it has altered international alliances revealing the prospect of a new Cold War involving the United States, Russia, and China; and it has reshaped politics on left and right—often moving elements of the left to the right—in countries around the world. Most worrying, it has raised the possibility of a conflict between NATO and Russia, which might mean a nuclear war.

Everywhere people with compassion naturally hope for an end to this deadly and increasingly dangerous war. At the same time, most recognize that it should not be ended at the expense of Ukraine, a former colony fighting for its independence and for its life against Russian imperialism. At stake in this war are the questions of the right of the people of Ukraine to self-determination and of an oppressed people to resist and to seek the arms they need to repel an imperial power. This is a war both to stop Russian imperialist aggression and to resist the expansion of Vladimir Putin’s authoritarian regime. Those on the left today defend Ukrainian democracy, however limited and flawed and even though it is increasingly repressive; in particular we support the workers and their unions, feminists, and socialists and other leftists in Ukraine as they fight both against Putin’s dictatorship and simultaneously resist Volodymyr Zelensky’s neoliberal politics. In a broader perspective and in the longer term, what is at question in this war is expanding international solidarity among working people and the oppressed in the struggle against capitalism and imperialism. For all of these reasons, it remains absolutely necessary that we continue to stand with Ukraine.

This article will put Ukraine’s defensive war against Russian aggression in both an historical and theoretical context. We begin by looking at the history of Russian imperialism in Eastern Europe and other regions, then at the war on Ukraine and where it stands today; next we turn to look at the war’s impact on the left both in the United States and around the world; and finally, we argue that a correct response to the war can only be found in the politics of what we call “socialism from below.”

From Tsarist Imperialism to Soviet Imperialism

Imperialism, the domination of one nation over another, has existed since ancient times and taken many forms. Ukraine has long been a victim of Russian imperialism, pre-capitalist, capitalist, Soviet, and then state-capitalist. The Grand Duchy of Moscow, which later became the Russian empire, began to expand from the region surrounding Moscow in the sixteenth century and in about 150 years conquered the enormous territory from the Caspian and Black seas to the Pacific Ocean. Lenin called this “military feudal imperialism,” driven by a desire to increase the Tsars’ political power and wealth through the acquisition of territory, resources, and subject peoples. Finland, the Baltic states, a good part of Poland, and virtually all of central Asia became part of the empire. In the course of that expansion, Russia also took much of Ukraine, though Poland and the Austrian empire also laid claim to parts of it. The Tsars incorporated Ukraine into the Russian empire and instituted a policy of Russification, imposing the Russian language and culture on the country. But Ukrainian identity could not be erased.

Much like other nations in Eastern Europe in the nineteenth century, Ukrainian intellectuals developed a nationalist ideology that coincided with a popular movement that called for autonomy or independence for Ukraine. The Ukrainians’ opportunity to free themselves from Russian domination came at the end of the First World War with the Russian Revolution of October 1917 that established in Russia a new government of soviets (workers’ councils) headed by the Bolshevik Party (the future Communist Party) led by Vladimir Lenin. While Lenin called for the “right of nations to self-determination,” the Bolsheviks were initially hostile to, then divided on the question of Ukrainian independence, but eventually, tactically they came to support it. To win backing for the soviet revolution in Ukraine, it was necessary to adopt a position of national independence, and to maintain a Soviet Ukraine, it was necessary to bring together the peasant majority with the Donbas region working class in the east.[1] After a few tumultuous years of civil war, Ukraine, now at least nominally an independent nation, became, together with Russia, Transcaucasia and Byelorussia, one of the four founding governments of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics in 1922. But Ukraine’s period of independence within the USSR was short lived. Soviet Russia soon came to dominate Ukraine.

The Soviet subjugation of Ukraine has to be put in a broader historical context. After the death in 1924 of Lenin, Joseph Stalin’s faction by 1929 won control of the Communist party, the government, and the Communist International that controlled Communist parties around the world. In the period from 1929 to1939, Stalin led a counter-revolution, eliminating all democratic discussion within the party, reducing the Soviets to mere rubber stamps for policies decided by the party leadership, taking control of the labor unions, turning them into organizations to increase production, and eliminating all independent organizations in the society. Within the party, Stalin purged the Old Bolsheviks who had led the revolution, killing tens of thousands of them and putting another 100,000 in the gulags. The Communist Party fused with the government bureaucracy in a one-party-state that effectively owned and controlled all the means of production—mines, factories, and farms — carried out a violently coerced collectivization of agriculture; and inaugurated a forced march to industrialization. The Five-Year plans, created by the bureaucracy from above, established the general direction and goals of the economy, goals to be achieved by the intense exploitation of workers and the expropriation of peasants. Communist Party leaders who administered the society became a privileged class enjoying a higher standard of living and more opportunities for themselves and their families.

The new regime and its political-economic system is best described as bureaucratic collectivism, because it was neither capitalist nor socialist.[2] It was not capitalist because capitalist private property and the market were not the basis of the economy and it was not socialist because workers and the people of the country did not democratically control the economy. Bureaucratic collectivism was hostile to both capitalism and to socialism or those who fought for socialism which now existed nowhere. In the course of its development as an enormous new state—and a new kind of society stretching across Europe and Asia—it evolved into an imperialist power.

During Stalin’s rule and after, the ethnic Great Russians dominated the party-government and they came to hold the racist notion that they should dominate it, so what is called Great Russian chauvinism persisted despite the official ideology of “internationalism” and the “unity of the people.” As Zbigniew Marcin Kowalewski writes, “With the establishment of the Stalinist regime, we witnessed the restoration of Russia’s imperialist domination over all these peoples, once conquered and colonized, who remained within the borders of the USSR where they constituted half of the population, as well as over the new protectorates: Mongolia and Tuva [in southern Siberia].”[3] The Soviet Union made colonies of the nationalities and peoples within its boundaries, and the internal colonies provided economic resources to the Great Russian bureaucratic elite at the core. As Kowalewski writes, “The colonial division of labor distorted or even hindered development, sometimes even transformed republics and peripheral regions into sources of raw materials and areas of monoculture.”[4]

Stalin’s collectivization and industrialization were not always rational, efficient, or humane; on the contrary, they were brutal, murderous, and often counterproductive. In the course of the collectivization of agriculture in the USSR, some 7 to 10 million people died, while in Ukraine it is estimated Stalin killed 3.3 million people in 1932-33 in what was known as the Holodomor, which means death by hunger. Virtually all historians agree that this mass starvation was a human-made event; some argue that Stalin planned it, and some consider this premeditated and forced starvation to have been genocide.[5] In addition, In Ukraine, Stalin also had thousands shot and millions sent to labor camps in 1939 and 1944.[6]

The European great powers and especially Germany, threatened the Soviet Union, but Stalin responded by revealing his own imperialist goals. Stalin negotiated with Adolf Hitler, head of the Nazi Party and the German state, what was called a mutual non-aggression pact but which also contained a secret protocol recognizing each nation’s sphere of influence. On the basis of that, on September 1, 1939, Hitler ordered German troops to invade Poland, and Stalin did the same on September 17, eliminating Poland from the map, so that Germany and the Soviet Union now shared a common border.

The Soviet Union’s absorption of eastern Poland was soon followed by its invasion of Finland in the Winter War or First Soviet-Finnish War on November 30, 1939. Stalin had demanded that Finland cede territory in the Soviet Union so that it could better defend Leningrad (St. Petersburg), offering other territory in exchange. When Finland refused, Soviet troops invaded Finland, perhaps with the goal of conquering the entire country, but the Finn’s resistance led to the Moscow Peace Treaty in which on March 12, 1940 Finland ceded 9 percent of its territory. Some have argued that Stalin had brilliantly maneuvered to buy time and win territory before a German attack on the Soviet Union. Yet, whatever the motives, Stalin’s Soviet Union had become an imperial power that waged war to seize territory in both Poland and Finland. We could call this the beginning of Soviet imperialism, as long as we acknowledge the pre-existing imperial and colonial relationship of Great Russia to the peoples within the USSR.

When Hitler invaded the Soviet Union in June 1941, Stalin joined the Allies, which after December 1941 included the United States, whose Pearl Harbor naval base had been bombed by Japan on December 7. The Soviet Union first resisted and then overcame the German invasion at the battle of Stalingrad in February 1943 and within a year the Soviet Red Army began to move westward across Eastern Europe. During and immediately after the war,

In Europe, the Soviet Union incorporated the western regions of Belarus and Ukraine, Subcarpathian Ukraine, Bessarabia, Lithuania, Latvia, Estonia, part of East Prussia and Finland, and in Asia Tuva and the southern Kuril Islands. Its control has been extended throughout Eastern Europe. The USSR postulated that Libya be placed under its tutelage (22). It tried to impose its protectorate on the major Chinese border provinces – Xinjiang (Sin-kiang) and Manchuria. Moreover, it wanted to annex northern Iran and eastern Turkey, exploiting the aspiration for liberation and unification of many local peoples.[7]

That was only the beginning.

The Post-War Expansion of the Soviet Sphere

To understand Ukraine and its situation since World War II, it is necessary to grasp the context of Soviet imperialism in that era. In the last two years of the war, as the Red Army moved across Europe, it liberated the nations of the region of the Nazi-aligned regimes that had ruled them, but also in several nations simultaneously put in power governments called “People’s Republics,” usually dominated by Communists, and consequently most of these Peoples Republics became Communist governments by 1948. The experiences of Bulgaria, Romania, Hungary, Poland, and East Germany were in each case different during the People’s Republic period in which Communists were allied with Socialist, nationalist, or peasant parties. In some cases, such as Czechoslovakia, the final step was a general strike or a coup d’état, but the outcome everywhere was the same: The establishment of a Soviet-style Communist government. The two exceptions to this experience were Yugoslavia and Albania where a Communist-led partisan movements had liberated the country from the Nazis and their allies and established Communist governments.

The Soviet Union subsequently dominated all of these countries that had been liberated by the Red Army, rather than their own partisan forces through several institutions and mechanisms. First, the former Communist International, which had during the war been renamed the Communist Information Bureau, remained controlled by the Soviet Union and its Communist Party led by Stalin. It directed both Communist Parties that now ruled in Eastern Europe as well as those around the world, in Europe and Asia, as well as in Africa, Latin America and North America. In the Eastern European Communist states, it strove to create what Moscow called “socialism,” that is governments, economic systems, and societies that replicated the Soviet system in every possible way, from the so-called “Marxist-Leninist” ideology to the secret police. As Tony Judt writes “Where Stalin differed from other empire-builders, was in his insistence upon reproducing in the territories under his control forms of government and society identical to those of the Soviet Union.”[8]

Second, in 1949, in response to the U.S. Marshall Plan that aided in the rebuilding of capitalism and the establishment of liberal democratic states in Western Europe, the Soviet Union brought Bulgaria, Czechoslovakia, Hungary, Poland, Romania, and Albania into its Council for Mutual Economic Assistance or Comecon. As Tony Judt writes, “What happened in 1945 was that the Soviet Union took over, quite literally, where the Germans had left off, attaching eastern Europe to its own economy as a resource to be exploited at will.”[9] Comecon allowed the Soviet Union to play a greater role in the management of the Eastern European national economies for the benefit of Soviet Russia. Stalin demanded that they model themselves on the Soviet experience, recapitulate Soviet industrialization—ridiculous in industrial Czechoslovakia—and establish their own Five-Year Plans.

Third, after Stalin’s death and under his successor Nikita Khrushchev, the Soviet Union created the Warsaw Pact, a military alliance of the Eastern Bloc to counterbalance the power of the Western powers’ North Atlantic Treaty Organization or NATO. Ostensibly it was created to defend the Communist countries against NATO, with which there was never a confrontation.

The Soviet Union, a bureaucratic collectivist state and society, was not only an imperial power, but it was also, like capitalism, a growing and spreading social system in the mid-twentieth century. The Soviet Union under Stalin and his successors supported the Communist Party of China in the revolution it carried out there, coming to power in 1949, and supported the Communist governments in North Korea and in North Vietnam. After the Cuban Revolution of 1959, the USSR also became a model for and a sustainer of Communist Cuba. The Soviet Communists, however, did not have the power to control those states as they did the countries of Eastern Europe, and all three Asian states later in different ways broke with the USSR.

The Colonies Resistance to the Soviet Union

Soviet imperialism did not go unchallenged. The four most important rebellions against it were the East German workers rebellion of 1953, the Hungarian Revolution of 1956, the Czech Prague Spring of 1968, and the Polish Solidarność strike movement of 1980; all combined elements of a struggle for national independence, for democratic government, and to varying degrees for workers’ power. In both Hungary and Poland, the workers movement took on the form of soviets or workers councils that had been the basis of the Russian Revolution of 1917.The Soviet Union responded to all four with force or the threat of force.

A strike against production quotas by East German workers began in June of 1953 and soon spread to hundreds of towns and involved hundreds of thousands of people. The Soviet Army still occupied the country and many Germans resented the Sovietization of their country, making its economy and political system identical to those of the Soviet Union. The movement spread throughout East Germany. In some cities, tens of thousands participated in protest. Soon the workers were calling for “free elections” and carrying shouting slogans like, “Down with the government.” The Soviet Communist party ordered the suppression of the rebellion and Soviet tanks and troops were sent to East Berlin. Ten thousand protestors were arrested and more than 30 executed.

The Hungarian working class revolted in 1956, forming a government of workers’ councils. The workers revolt became a revolution demanding the removal of all Soviet troops, the election of all Communist Party officials, election of government officials by secret ballot, removal of former Stalinist leaders, freedom of speech and of the press, and removal of the statue of Stalin, among others. Nikita Khrushchev, Stalin’s successor as leader of the Soviet Union, seeing the danger to the whole Soviet Eastern Bloc, ordered an invasion of over 1,000 tanks and more than 30,000 soldiers, and working with the Hungarian Communist Party violently suppressed the national uprising, killing 2,500 Hungarians and leading more than 200,000 to flee the country.

In Czechoslovakia in 1968 a reform movement arose demanding democracy and the Czech Communist government of Alexander Dubček responded positively with an “Action Program” calling for a liberalization of the media and even the possibility of a multi-party government. In response, Leonid Brezhnev ordered the Soviet Army and other Warsaw Pact troops with 2,000 tanks and 200,000 soldiers to invade and occupy the country and suppress the democratic movement, in the course of which 72 were killed, while 70,000 fled the country immediately and 300,000 eventually.

In Poland in August 1980, a workers movement originating in the port city of Gdansk created an independent labor union and taking the name Solidarność (Solidarity) began a series of strikes that eventually spread across the entire country, with the union reaching 10 million members by September 1981. Faced with the prospect of a worker-led democratic, national liberation movement, General Wojciech Jaruzelski declared martial look and took power. He said that he had declared martial law to a avoid a Soviet invasion, and indeed, with the strike wave crushed by Polish forces, there was no need for Soviet troops. While Solidarność initially had a democratic socialist character, the Catholic Church and U.S. President Ronald Reagan both intervened in the movement, drawing it in subsequent years in a more conservative direction.

The Solidarity movement for workers’ power, democracy, and national independence had an enormous impact throughout the Communist world and signaled the coming end of the bureaucratic collectivist system in the entire Eastern Bloc and in the Soviet Union. Under various pressures, from Russian defeat in its war on Afghanistan, to the Polish Solidarity movement, to the growing concern that the Soviet Union was falling behind Europe and the United State, to rebellions in some of the Soviet Republics and the movement of others to secede, as well as in reaction to the reforms initiated under Soviet head-of-state Mikhail Gorbachev and the growth of pro-democracy political movements, the Soviet Union and its empire began to fall apart. In November 1989, the Communist East German government allowed the opening of the Berlin wall that divided the city half, half capitalist and democratic and half Communist and totalitarian, at which point Germans on both sides began to demolish the wall that had symbolized an era. A little ore than a yer later, in 1991 Boris Yeltsin dissolved the USSR. Shortly afterward in Ukraine, the government held a referendum on independence in December of that year and a remarkable 92.3% of voters declared their desire to establish an independent nation. Countries around the world immediately recognized Ukraine as a sovereign country. Ukraine’s second period of independence since the early 1920s began.

Independent Ukraine experienced a period of economic challenges and political instability under several presidents, the last being Viktor Yanukovych. When he declined an affiliation with the European Union and instead sought closer ties with Russia, there was a popular revolt known as the Maidan or Dignity Revolution. While some have characterized this a movement created by Western powers and Ukrainian Nazis, it was fundamentally a national democratic revolution. Following this Ukraine sought closer relations with the West, which prompted Putin to invade Crimea, which we take up below.

Post-Soviet Russia and Putin’s Imperialism

Within Russia, Yeltsin initiated a new period of political democracy and of liberal economic reforms, though in fact the political system remained corrupt and the economy was not actually liberalized. At all levels the former Communist bureaucrats seized whatever they could—taking over cities or states, mines and factories, whatever was of value—and some became part of the new governmental elite while others evolved into the new class of oligarchs. As one authority writes, “…with the collapse of state control over production on the one hand and absence of the legal basis of private property on the other, control over the assets was gained and retained by force, the use of criminal structures and bribery of government officials.”[10] Dzarasov, writes, “In reality, privatization turned out to be the massive transfer of property rights from the state to the most unscrupulous representatives of the ruling bureaucracy, the acquisitive class and the criminal underworld, at the expense of the absolute majority of Russian citizens.”[11] At the same time, Putin and the political elite colluded with the criminal oligarchs, sometimes cajoled and even jailed them to preserve the order of the new system of bureaucratic capitalism. As Boris Kagarlitsky wrote in 2002,

Russia is a capitalist country to the extent that it is part of the global capitalist economy. At the same time, Russia remains communal, corporatist, authoritarian, ‘Asiatic,’ and even feudal-bureaucratic. A sort of transmuted variant of bureaucratic collectivism, continuing the social tradition of the Soviet statocracy, holds sway here. The difference is that the ‘socialist’ decorations have been taken down, and the real elements of socialism that existed in Soviet society have been extirpated or weakened.[12]

Economic changes under Gorbachev, Yeltsin, and Putin were supposed to create a modern liberal state and a more efficient economy, but they fundamentally failed to do so. The economy was to be privatized, a mark was to be created, and capitalism was to flourish. The oligarchs who appropriated the formerly state-owned enterprises proved to be inept capitalists. The economy failed to prosper and consequently, the Russian economy is still largely state-owned, or better, once again state-owned, largely because it gave Putin great power to keep the oligarchy in line.

The largest state-owned companies are quasi-monopolies and they dominate the Russian economy. “The general tendency of expanding the state share in the economy became more evident and steadier after the financial crisis of 2008. The growing state share also contributed to further ownership concentration.”[13] A 2022 report on Russian state-owned enterprises explains that, “The Federal Antimonopoly Service of the Russian Federation revealed that the combined contribution of SOEs to Russia’s GDP in 2015 was about 70 per cent, while that share did not exceed 35 per cent in 2005. In 2018, that share reached 60 per cent.”[14] The enterprises have not been corporatized and are owned and managed directly by the state, while many other large corporations are partnerships with the oligarchs or solely in their hands.

Despite the economic changes of the last few decades oil and gas remain the mainstay of the Russian economy. “Russia’s oil and gas industry accounted for around 18 percent of the country’s gross domestic product (GDP) between July and September 2022. That constituted a decrease compared to the peak level of 21.7 percent in the first three months of the year.”[15] According to the International Energy Agency, revenue from oil and gas alone made up 45 percent of Russia’s federal budget.[16] It is oil and gas that despite U.S., European and Japanese sanctions, kept Russia’s economy from collapsing as some predicted and they have made it possible for Putin to continue funding the war in Ukraine.

With the fall of Communism, Russia’s bureaucratic collectivist political economy morphed into a state capitalist economy, and under Putin, the state keeps the capitalist class, made up of an oligarchy of kleptomaniacs and criminals in line, imprisoning them when necessary to make a point. Modernization in the sense of creating a liberal economy largely failed, in part because the corrupt state had continued to increase its role in the economy. Russia, with its enormous territory, large population, and great natural resources is eleventh in GDP, behind South Korea and Brazil.

Once a great power, even with its oil wealth, Russia is now a second-rate country in terms of economic power, and it is this that rankles Putin. Russia’s weak economy is one of the reasons that he has turned to imperial wars, particularly the war in Ukraine, the conquest of which would bring greater wealth to Russia, principally from agriculture but also from mining, chemicals, and manufacturing, and now oil from the Black Sea.

Putin’s geopolitical concerns and his material, economic objectives may not be more important than his ideological and geopolitical goals. His imperial ideology is a throwback to Tsarist Russia. Putin—influenced by rightwing intellectuals like Lev Gumilev and Alexander Dugin—believes (or claims he believes) in the thousand-year-old Russia. He sees the Russia of the old Tsarist empire, infused by a cosmic force of “passionate power” (Gumilev), inspired by the Russian Orthodox Church, the archetypal Slavic nation, speaking Russian, and leading the other Slavic peoples and the neighboring Asians in the creation of a Eurasian power than can stop and challenge and defeat the West.

Fearing that the morally bankrupt West is encroaching on Russia, Putin believes that the Russian empire must be recreated and those “fellow citizens and countrymen [who] found themselves beyond the fringes of Russian territory” must be rescued and reincorporated into Russia. Most important of those are the Ukrainians, a nation as large as France with a population of more than forty million people, with its own history, language, and culture whose very existence Putin has denied. In 2019, Putin told filmmaker Oliver Stone, “I believe that Russians and Ukrainians are one people … one nation, in fact,” Putin said. “When these lands that are now the core of Ukraine joined Russia … nobody thought of themselves as anything but Russians.” Nobody but the Ukrainians.

Putin rejects the idea of a Ukrainian people and nation, arguing that Ukraine is an artificial creation. “Modern Ukraine was entirely and fully created by Russia, more specifically the Bolshevik, Communist Russia,” Putin said in 2021. “This process began practically immediately after the 1917 revolution, and moreover Lenin and his associates did it in the sloppiest way in relation to Russia — by dividing, tearing from her pieces of her own historical territory.” He has also written an article arguing this position. His position thus denies the Ukrainian people any agency, any ability to decide their own identity. Clearly this position becomes a justification for war against the Ukrainians to force them to become part of Russia. Such an ethno-nationalist, civilizational ideology has been used by Putin to justify conquest, mass murder, and ethnocide. Russia’s second-rate economic and political status created a material basis for imperialist war, and his ethno-nationalism provided an ideological theory and justification for it, but a theory that is as much responsible for the imperialist war as the economy.

Putin’s regime has been characterized by wars against former republics or regions of the USSR: Chechnya, Georgia, and Ukraine, as well as a war in Syria. The strategies and tactics in these wars have been similar. The Russian Army being generally incompetent, Putin and the generals compensate by massive attacks on the civilian population by both the army on the ground and bombing from the air. This produces large numbers of civilian deaths, displacement of civilian populations, and the economic and social disabling of the country under attack. These imperialist wars strive to maintain the former Tsarist and Soviet colonies under Russian control.

Putin began his political career overseeing a brutal and devasting war against Chechnya, supposedly fighting a war of counter-insurgency against Chechen separatist terrorists, though the FSB security services, of which Putin was the director until he became prime minister in August 1999, may have actually committed the bombings that were used as justification for the war. Journalist Anna Politkovskaya, who was assassinated in 2006, wrote, “The army and police—nearly one hundred thousand strong—wandered around Chechnya in a complete state of moral decay.”[17] What did she mean? She meant this:

Following an investigative mission to Chechnya in February 2000, the International Federation for Human Rights (FIDH) listed these violations as follows: ‘destruction of towns and villages unjustified by military necessity; bombardments of and assaults on undefended towns and villages; summary executions and murders, physical abuse and torture; intentionally causing grave harm to people not directly involved in hostilities; deliberate attacks on the civilian population, on public transport and health workers; arbitrary arrest and detention of civilians; looting of private property.’[18]

The war went on from 1999 to 2009 accompanied by myriad war crimes and violations of human rights which some characterized as genocide.[19]

With the war still going on in Chechnya, in 2008 Putin’s government also launched a war against the Republic of Georgia, supposedly in defense of two Russian-backed, break-away, separatist republics, South Ossetia and Abkhazia. While all sides engaged in human rights violations, Russia appears to have been the greater offender.

Russian forces used cluster bombs in areas populated by civilians in the Gori and Kareli districts of Georgia, leading to civilian deaths and injuries. Russia also launched indiscriminate rocket attacks on civilian areas, causing casualties.[20]

Russia bombed schools and hospitals. A Human Rights Watch report said, “Russia bore responsibility but took no discernable measures on behalf of protected individuals, including prisoners of war, at least several of whom were executed or tortured, ill-treated, or subjected to degrading treatment by South Ossetian forces, at times with the participation of Russian forces.”[21] South Ossetian militias, uncontrolled and perhaps encouraged by Russia, robbed, murdered and raped. The European Court of Human Rights ruled in 2021 that Russia “was responsible for the murder of Georgian civilians, and the looting and burning of their homes.”

In 2015, Putin intervened in the Syria civil war on the side of the dictator Bashar al-Assad, conducting airstrikes. A Human Rights report on events of 2021 writes,

While all sides to the conflict have committed heinous laws-of-war violations, the Syrian-Russian military alliance has conducted indiscriminate aerial bombing of schools, hospitals, and markets—the civilian infrastructure essential to a society’s survival. According to Airwars, a UK-based monitoring group, the Russian air force alone has carried out around 39,000 airstrikes in Syria since 2015.[22]

All of Putin’s imperialist wars share the same characteristics: They are conducted against weaker nations using artillery and aerial bombardment with the intention of demoralizing the civilian population. Many of the Russian soldiers and all of the Wagner mercenaries behave savagely, killing indiscriminately, raping, and pillaging. Yet all of these wars have revealed the Russian military’s lack of strategic thinking and incompetence and have usually ended indecisively.

Ukraine War

The Russian War on Ukraine began in February of 2014 with Russia invading and then taking over Crimea and the city of Sebastopol. Crimean nationalists backed by Russia established a puppet government that declared the Republic of Crimea. A phony referendum held under Russian occupation with no free media or right to assemble and speak was held on March 14, with 95 percent voting for independence—though only 15 to 30 percent of Crimeans cast ballots. On March 18, Crimea’s bogus government voted to join the Russian Federation, a treaty of annexation was signed, and Russian forces seized the Ukrainian military bases. The United Nations and many countries refused to recognize the new Crimean Republic, declaring the referendum illegitimate. However, neither the UN or any coalition or individual nation took action to stop the Russian seizure of territory from another European state, the first time such a thing had happened since World War II. In seizing Crimea, Russia gained access to enormous oil reserves possibly worth trillions of dollars.[23]

The seizure of Crimea was accompanied by the opening of war in the Donbas region of Ukraine. The strategy was similar to that used in Crimea. Putin encouraged the creation of Russian-led separatist organizations and militias in Donetsk and Luhansk. Regular Russian military units joined the break-away states’ militias. These forces took over government buildings. As in Crimea, a phony referendum was held in mid-May and at the end of April the Luhansk People’s Republic and the Donetsk People’s. Both Republics claimed more territory than that actually held by their militias or Russian troops. On February 21, 2022, Putin recognized the two ersatz states and promised his support to them. Two days later he would launch his “special operation,” a full-scale war on Ukraine.

Vladimir Putin apparently believed his own myth of Russian cosmic force that could reunite the old Tsarist Empire and lead the Slavic people to create a new Eurasian force to counter the West, and so on February 24, 2022 he invaded Ukraine, evidently thinking his soldiers would enter Kiev and be greeted as liberators. It did not happen, the Ukrainians fought back, and the Russian Army was forced to retreat and regroup. Putin then turned to his traditional method of waging war, using artillery and airplanes to bombard Ukarine, often hitting hospitals, schools, power plants, other infrastructure and residential neighborhoods, taking thousands of Ukrainian lives. Yet by the fall of 2022, it was clear that while he could destroy much of Ukraine, he couldn’t necessarily defeat it, so he turned to another historic Russian strategy. He instituted a new draft with the goal of recruiting 300,000 men, intending to inundate and overwhelm Ukraine with soldiers and that’s what’s happening now on the eastern front.

The West’s Response to the War

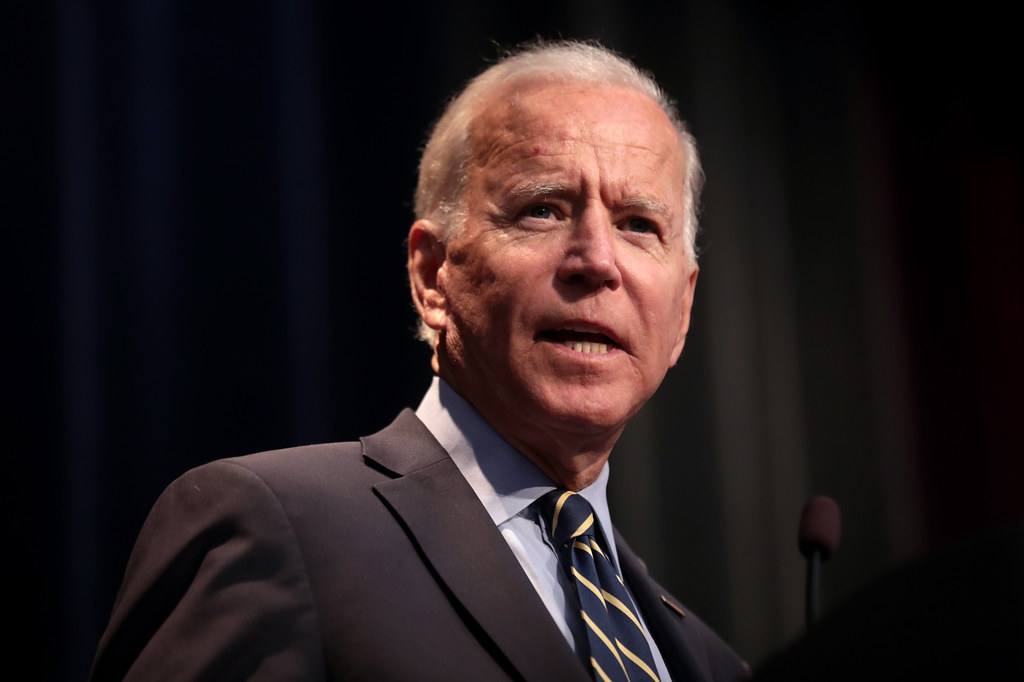

The response of the West, led by the United States, was swift. President Joseph Biden committed the United States to support Ukraine. The American president intervened forcefully to revive and reunite that North Atlantic Treaty Organization, appealed to the European Union and the G7 nations (United States, Canada, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, and the United Kingdom), and built a coalition of fifty countries around the world. Biden won over the progressives in his party and succeeded in uniting both Democrats and Republicans in Congress to vote to provide arms to Ukraine.

Biden’s support is not wavering. On the anniversary of the war, Biden took the risk of traveling to the Ukrainian capital of Kiev to speak with President Volodymyr Zelensky. “One year later,” Biden said, “Kyiv stands and Ukraine stands. Democracy stands. The Americans stand with you, and the world stands with you….We have every confidence that you’re going to continue to prevail….You remind us that freedom is priceless; it’s worth fighting for as long as it takes. And that’s how long we’re going to be with you, Mr. President: for as long as it takes.”

So far total U.S. spending on Ukraine is $77.5 billion, and on the anniversary of the war’s outbreak it was announced that the U.S. will spend another $2 billion more. While that is a lot of money, it is not a large part of the U.S. budget. The United States spends $1,340 billion on Social Security, $902 billion on Medicare, $734 billion on Medicaid, and billions more on other programs. The $77.5 billion for Ukraine breaks down into $29.3 billion in military assistance, $45 billion largely for economic recovery and energy infrastructure, and $1.9 billion for humanitarian assistance.

While there has been some fragmenting of political support, still Americans overwhelmingly support Biden’s position on Ukraine. The most recent Gallup Poll found that, “A stable 65% of U.S. adults prefer that the United States support Ukraine in reclaiming its territory, even if that results in a prolonged conflict. Meanwhile, 31% continue to say they would rather see the U.S. work to end the war quickly, even if this allows Russia to keep its territory.”

Biden and the Democrats continue to have extraordinary backing for their Ukraine policy. Top Republicans leaders. Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell recently declared, ““Republican leaders are committed to a strong trans-Atlantic alliance. We are committed to helping Ukraine.” Things are more difficult in the House, but even there the Republicans opposed to support for Ukraine are a small minority on the far-right wing. But Trump is campaigning against continued aid to Ukraine and this will put more pressure on Republicans. And some Americans, mostly Republicans, now complain that the United States is spending too much on aid to Ukraine.

The U.S. and NATO countries provided tens of billions of dollars of military and humanitarian assistance to Ukraine as well as imposing sanctions on Russia in an attempt to crush its economy and force it to withdraw from Ukraine and end the war. Russia, however, proved able to work around the sanctions selling its oil and gas and other produces to India and China. Still Russia is affected by its lack of imports from the West, leading it to turn to China for imports and forcing it to adopt a substitution of imports economy, that is, producing itself products previously imported, though this is a difficult long-term strategy. At the same time, Russia has militarized its economy, but to maintain military production it must draw on its financial reserves, and when they prove inadequate, it will have to turn to China. Russia’s war against the West may lead to its dependence on the East, subordination to China’s much stronger economy.[24]

The war has changed Russia’s political system as well as its economy. As Ilya Budraitskis writes, “…Putin’s regime has experienced a gradual evolution over twenty years from depoliticized neoliberal authoritarianism into a brutal dictatorship.”[25] Putin already had enormous power over the government, the economy, and through the state media of much of the society. Since he opened the war and took on the powers of a dictator some 200,000 Russian soldiers have been killed or wounded and an estimated 700,000 mostly young men have fled the country to avoid conscription. More than 15,000 protestors against the war in some 140 cities have been arrested. How many Russian support the war is unclear. Meduza, an opposition newspaper says it got hold of a government poll showing that only 25 percent of Russians support the war, while 55 percent want peace talks.[26] But a recent Levada poll says that 75 percent support the “actions of the Russian military in Ukraine.” In a society without free media and where people fear to express themselves, it is hard to get the pulse of the people. Still, it is clear that, like the U.S. war in Vietnam, the Russian war in Ukraine has created many problems for the government on every front and they will not be solved easily.

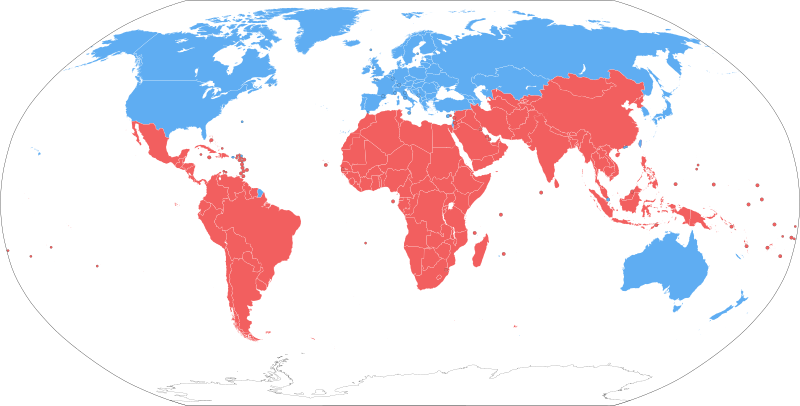

The war has changed the entire world. Europe is more united. Russia has created closer ties to China and India. Latin American and African nations have not played a very active role. Yet at a vote in the U.N. General Assembly calling for an end to the war and for Russia to leave Ukraine, 141 countries voted in favor of the resolution, 32 including China and India abstained; votes against were cast only by Belarus, North Korea, Eritrea, Mali, Nicaragua, Russia, and Syria. Most nations clearly recognize the importance of supporting the right to national sovereignty and territorial integrity and freedom from military invasion by a foreign power. The vote is an indication of Russia’s profound political isolation.

The Russian War on Ukraine has also affected the internal politics of countries around the world as Putin has continued to support far right parties as he has for more than a decade. Putin’s Christian Slavic ethnonationalism has made him a hero to ultra-right parties in Europe and to the ultra-white neofascists in the United States. He has invited these groups to conferences in Russia and supported Russian rightwing emissaries to meet with the far right in Europe and America. Donald Trump, who consistently praised Putin, set an example for other far right leaders in America. So far most of these groups, if no longer as marginal as they once were, remain a minority in most countries, though there are now such governments in Hungary and Italy.

For the left, one of the most disturbing results of the war has been the development of an alliance between the campist left, those who support nations opposed to the United States, and the far right. These groups find common ground in their support for Russia’s right to Ukaraine as an historical part of its empire. So far not very significant themselves, they become more important as part of the coalitions calling for “peace and diplomacy” with whom they mingle. So one can find people who called themselves communists or socialists and well-meaning pacifists now marching with the Libertarian Party, Trump supporters, Q-Anon cultists, anti-Vaxxers, and outright fascists.

The Dangers of the War and the Quest for Peace

Anyone who follows the Russian War on Ukraine at all recognizes the dangers posed by it, such as Russia turning to the use of tactical nuclear weapons and the possibility of a direct confrontation between Russia and NATO nations and the United States which could lead to a European war or even a world war, which means a nuclear war. So far, the United States and the European countries, while supporting Ukraine, have taken care not to provoke Russia. Still, Russia cannot be trusted and when wars break out, they can spiral out of control. We must remain aware of these dangers and take action and mobilize to prevent them if they arise.

How might the Russian War on Ukraine end? Almost all modern wars end through diplomacy and the negotiation of a treaty, a process that often begins with a cease-fire and then a truce. Diplomacy at this time seems virtually impossible. Putin shows no desire to negotiate, at least not without keeping Crimea and keeping the Donbas region. And Zelensky has proposed a peace plan based on the withdrawal of all Russian troops and the restoration of Ukraine’s territorial integrity, but it also includes the establishment of a special tribunal to try Russians guilty of war crimes.[27] While all of these demands are reasonable and just, Putin will certainly not agree to them. Most recently China has proposed its own 12-point peace plan, and while all of its points are quite reasonable—such as a cessation of hostilities and respect for all nations’ territorial integrity—the essential point, the withdrawal of Russia’s troops is missing. Moreover, China cannot both attempt to be a peacemaker in good faith while it allows speculation that it might provide arms to Russia. So at the moment call for an immediate cease-fire and peace through diplomacy with Russia occupying twenty percent of Ukraine, is simply a call for Ukrainian defeat and Russian victory.

Given this, we on the international socialist left continue to support Ukraine. First, because Russia is the aggressor and Ukraine is the victim, so we support it as we have other colonies and former colonies around the world in the past, as in the case of Vietnam for example. Second, we support it because we believe Ukraine is a democratic nation (however flawed) while Russia is an authoritarian country, a dictatorship. A victory for Russia would mean an end to free speech and free press, the crushing of independent social movements, and the persecution of LGBTQ people just as is done in Russia now. Third, a victory for Putin would encourage him to continue his project of reconstructing the Tsarist and Soviet empires, perhaps next in Moldova, or in the Baltic countries, or who knows where.

While we support Ukraine and the Ukrainian people in general in this war, we also recognize that Volodymyr Zelensky, courageous a leader as he may be, holds conservative, neoliberal views that would enrich the Ukrainian capitalist class at the expense of the middle classes, the working class, and the poor. So we support the socialist group Sotsialnyi Rukh (Social Movement or SR) and the independent labor unions and social movements it works with, and the independent left press Commons. We also align ourselves with the Russian ant-war movement, much of it now in jail or in exile, as represented by the journal Posle. We also stand in solidarity with the Ukraine Solidarity Networks in the United States and Europe.

The principles of our support are simple. A people and a nation have the right to self-determination, to sovereignty and territorial integrity, and to defend themselves. When such a nation is attacked, it is also an attack on those principles and therefore on the rest of us. So we must stand with Ukraine.

Notes:

Thanks to my friend and comrade Stephen R. Shalom for his editing and suggestions.

[1] Hanna Perkhoda, “When the Bolsheviks Created a Soviet Republic in the Donbas,” Jacobin, March 22, 2022, at: https://jacobin.com/2022/03/bolshevik-soviet-republic-donbas-ukraine-national-question-lenin-putin-ussr and Hanna Perekhoda, “Les bolcheviks et l’enjeu territorial de l’Ukraine de l’Est (1917–1918), Cevipol of the Université libre de Bruxelles and the Global Studies Institute of the University of Geneva.

[2] Some called the Soviet Union state capitalist, but I believe this is mistaken because within its borders there was no private property, commodities were not sold on the market but distributed by the state, and labor was not a commodity sold on the market but allocated by the state.

[3] Zbigniew Marcin Kowalewski, “Russian Imperialism: From the Tsar to Today, via Stalin, the Imperialist Will Marks the History of Russia,” New Politics, March 4, 2022.

[4] Kowalewski, “Russian imperialism.”

[5] Timothy Snyder, Bloodlands: Europe Between Hitler and Stalin (New York: Basic Books, 2010), p42. He writes: “In the waning weeks of 1932, facing no external security threat and no challenge from within, with no conceivable justification except to prove the inevitability of his rule, Stalin chose to kill millions of people in Soviet Ukraine. … Though collectivization was a disaster everywhere in the Soviet Union, the evidence of clearly premediated mass murder on the scale of millions is most evident in Soviet Ukraine.” See also, Anne Applebaum, Red Famine: Stalin’s War on Ukraine (New York: Penguin Random House, 2017), p. 226, “Stalin’s policies that autumn [of 1934] led inexorably to famine across the grain-growing regions of the USSR. But in November and December 1932 he twisted the knife further in Ukraine, deliberately creating a greater crisis. Step by step, using bureaucratic language and dull legal terminology, the Soviet leadership, aided by their cowed Ukrainian counter-parts, launched a famine within the famine, a disaster specifically targeted at Ukraine and the Ukrainians.”

[6] Robert Conquest, Harvest of Sorrow: Soviet Collectivization and the Terror-Famine (New York: Oxford University Press). p. 334.

[7] Kowalewski, “Russian Imperialism.”

[8] Tony Judt, Postwar: A History of Europe Since 1945 (New York: Penguin Books, 2005), p. 167.

[9] Judt, Postwar, p. 167.

[10] A. Ragydin and I. Sydorov, … in Rusla Dzarsov, The Conundrum of Russian Capitalism ( ) , p. 67.

[11] Dsarsov, The Conundrom, p. 72.

[12] Boris Kagarlitsky, Russia Under Yeltsin and Putin (London: Pluto Press, 2002), p. 7.

[13] Roza Nurgozhayeva, “Corporate Governance In Russian State-Owned Enterprises: Real Or Surreal?

Published online by Cambridge University Press, April 5, 2022, at: https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/asian-journal-of-comparative-law/article/corporate-governance-in-russian-stateowned-enterprises-real-or-surreal/2F4F08667E5F13A390BADBA0F9164A51

[14] Ibid. See her article for her sources.

[15] Statista Research Department, Jan 16, 2023, at: https://www.statista.com/statistics/1322102/gdp-share-oil-gas-sector-russia/#statisticContainer

[16] Hiro Tabuchi, “Russia’s Oil Revenue Soars Despite Sanctions, Study Finds,” New York Times, June 13, 2022.

[17] Anna Politkovskaya, A Small Corner of Hell: Dispatches from Chechnya (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2007), p. 28.

[18] Anne le Huérou Amandine Regamey, “Massacres of Civilians in Chechnya,” Science Po, Mass Violence & Resistance (MV&R), at: https://www.sciencespo.fr/mass-violence-war-massacre-resistance/en/content/about-us.html

[19] Including the Ukrainian parliament in October 2022.

[20] “Russia Events: 2008,” Human Rights Watch, at: https://www.hrw.org/world-report/2009/country-chapters/russia

[21] Human Rights Watch, “Up In Flames,” January 23, 2009, at: https://casebook.icrc.org/case-study/georgiarussia-human-rights-watchs-report-conflict-south-ossetia

[22] “Syria: Events of 2021,” Human Rights Watch, https://www.hrw.org/world-report/2022/country-chapters/syria

[23] William J. Broad, “In Taking Crimea, Putin Gains a Sea of Fuel Reserves,” New York Times, May 27, 2014, at: https://www.nytimes.com/2014/05/18/world/europe/in-taking-crimea-putin-gains-a-sea-of-fuel-reserves.html

[24] Romaric Godin, “L’économie russe en voie de militarisation totale,” Mediapart, February 26, 2023.

[25] Ilya Budraitskis, “Putinism: A New Form of Fascism?”, Spectre, October 27, 2022, at: https://spectrejournal.com/putinism/

[26] Andrey Pertsev, “Make Peace Not War,” Meduza, Nov. 30, 2022, at: https://meduza.io/en/feature/2022/11/30/make-peace-not-war

[27] “What is Zelenskyy’s 10-Point Peace Plan? Aljazeera, Dec. 28, 2022.

In the month of the first anniversary of Russia’s illegal and brutal full-scale invasion of Ukraine, president Volodymyr Zelensky

In the month of the first anniversary of Russia’s illegal and brutal full-scale invasion of Ukraine, president Volodymyr Zelensky

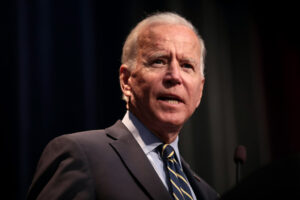

Joe Biden comes to Ireland this week, looking for iconic moments to reinforce and revive the promises made by Bill Clinton to the people of the North after the Good Friday Agreement and in pursuit for his homecoming moment like John F. Kennedy in the 60s. He’ll get neither in terms of the cultural impact and hysteria of these two previous presidents. The fact of the matter is that the two of them sold Ireland dreams, and today’s Ireland, which contains two failed states north and south of the border, cannot dream.

Joe Biden comes to Ireland this week, looking for iconic moments to reinforce and revive the promises made by Bill Clinton to the people of the North after the Good Friday Agreement and in pursuit for his homecoming moment like John F. Kennedy in the 60s. He’ll get neither in terms of the cultural impact and hysteria of these two previous presidents. The fact of the matter is that the two of them sold Ireland dreams, and today’s Ireland, which contains two failed states north and south of the border, cannot dream. Biden’s visit is timely as Fine Gael and Fianna Fail as well as allied media punditry are pushing to re-examine the state’s longstanding principle of neutrality and manufacture consent for NATO membership. Just this past week, the government has put forward ‘public forums’ to gauge interest in a reversal of this policy. Opposition have described this as propaganda, and a thinly-veiled attempt to stoke interest and make the prospect more appetizing to the public.

Biden’s visit is timely as Fine Gael and Fianna Fail as well as allied media punditry are pushing to re-examine the state’s longstanding principle of neutrality and manufacture consent for NATO membership. Just this past week, the government has put forward ‘public forums’ to gauge interest in a reversal of this policy. Opposition have described this as propaganda, and a thinly-veiled attempt to stoke interest and make the prospect more appetizing to the public.

I came of political age as an opponent of the U.S. war in Vietnam. Since then, I have protested against U.S. wars in Central America, Israel’s wars against Palestinians, the war in Afghanistan and the invasion of Iraq. But though I am an anti-war activist, I am not an absolute pacifist.

I came of political age as an opponent of the U.S. war in Vietnam. Since then, I have protested against U.S. wars in Central America, Israel’s wars against Palestinians, the war in Afghanistan and the invasion of Iraq. But though I am an anti-war activist, I am not an absolute pacifist.

The Russian war on Ukraine is the result of the imperialist ideology and the economic and geopolitical objectives of Vladimir Putin and the Russian state. Russia is, as it has long been, an imperial power seeking to eliminate Ukraine as an independent state and even to erase the Ukrainians as a people. The roots of this Russian aggression are to be found in the Tsarist and more particularly in the Soviet regime, imperial ambitions now embodied in Putin and his regime. The purpose of this article is to explain the origin and evolution of Russian imperialism and to discuss the war on Ukraine in that light of that understanding. I believe that this history is necessary in order to understand Russia and its relationship to Eastern Europe and in particular to Ukraine.

The Russian war on Ukraine is the result of the imperialist ideology and the economic and geopolitical objectives of Vladimir Putin and the Russian state. Russia is, as it has long been, an imperial power seeking to eliminate Ukraine as an independent state and even to erase the Ukrainians as a people. The roots of this Russian aggression are to be found in the Tsarist and more particularly in the Soviet regime, imperial ambitions now embodied in Putin and his regime. The purpose of this article is to explain the origin and evolution of Russian imperialism and to discuss the war on Ukraine in that light of that understanding. I believe that this history is necessary in order to understand Russia and its relationship to Eastern Europe and in particular to Ukraine.

Review: Fred Leplat and Chris Ford (eds.),

Review: Fred Leplat and Chris Ford (eds.),

For a year now, Vladimir Putin’s regime has been killing Ukrainians, sending hundreds of thousands of Russians to their deaths, and threatening the world with nuclear weapons in the name of the insane goal of restoring its empire.

For a year now, Vladimir Putin’s regime has been killing Ukrainians, sending hundreds of thousands of Russians to their deaths, and threatening the world with nuclear weapons in the name of the insane goal of restoring its empire.

With the advent of modern medical technology, it is now possible to keep people alive longer, in chronically sicker states of health, at higher rates than ever before. Think of technologies like left ventricular assist devices, organ transplants, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation, and monoclonal antibodies. These therapies come with a hefty price tag. For example, Aducanumab, a monoclonal antibody, was recently approved by the FDA to treat Alzheimer’s disease. Its yearly cost is $56,000 and if it were to be given to every indicated patient,

With the advent of modern medical technology, it is now possible to keep people alive longer, in chronically sicker states of health, at higher rates than ever before. Think of technologies like left ventricular assist devices, organ transplants, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation, and monoclonal antibodies. These therapies come with a hefty price tag. For example, Aducanumab, a monoclonal antibody, was recently approved by the FDA to treat Alzheimer’s disease. Its yearly cost is $56,000 and if it were to be given to every indicated patient,

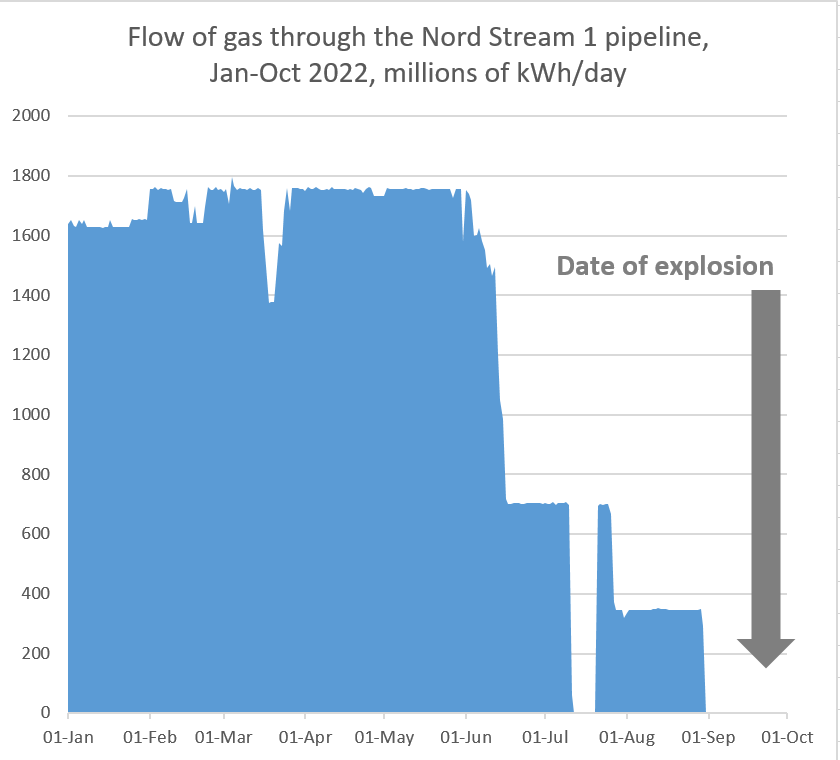

The claim that the Nord Stream gas pipeline was blown up by U.S. special forces,

The claim that the Nord Stream gas pipeline was blown up by U.S. special forces,

About a week ago, on February 9, Nicaraguan dictator Daniel Ortega released and deported 220 of his regime’s political prisoners. Taken from their prison cells, they were put on a plane, ignorant of the plane’s destination. One person speculated that they might be being sent to China. They were reportedly given a form to sign, saying that they were leaving Nicaraguan voluntarily. Two appear to have refused to sign the paper and go into exile, so they were returned to prison.

About a week ago, on February 9, Nicaraguan dictator Daniel Ortega released and deported 220 of his regime’s political prisoners. Taken from their prison cells, they were put on a plane, ignorant of the plane’s destination. One person speculated that they might be being sent to China. They were reportedly given a form to sign, saying that they were leaving Nicaraguan voluntarily. Two appear to have refused to sign the paper and go into exile, so they were returned to prison.

Those who choose not to see and not to hear

Those who choose not to see and not to hear