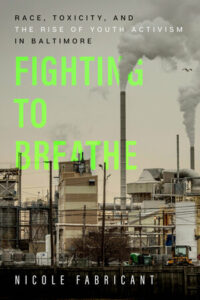

In this important new book, anthropologist and “activist ethnographer” Nicole Fabricant, known for her work on social movements and race in Bolivia, turns her attention to youth activism and environmental justice in the South Baltimore Peninsula, where a century of industrial development has produced a space of racial inequity and environmental hazards, including toxic air that makes breathing difficult. This book describes Fabricant’s work over ten years of participating with high school youth of color in movements aimed at eradicating inequalities in land use and waste management. Her wonderful book centers the voices and actions of students involved in campaigns to stop a trash incinerator as well as to create community land trusts to provide safe housing. Tracing both the successes and failures of a movement developing a radical political agenda, this book makes contributions to three areas of emerging research: community engaged research and decolonizing methods; youth politics and activism; and environmental justice and climate justice.

Community-engaged research and decolonizing methods: Fabricant makes clear from the beginning of the book that this is not a traditional academic ethnography. Rather than acting as an anthropologist employing the classic tool of ‘participant observation’, she identifies an activist engaged in ‘observant participation’. Drawing inspiration from her activist parents, Fabricant describes her own passion for community engagement and organizing. Her engagement in South Baltimore began in 2010, when she moved to Baltimore and became involved in the Environmental Justice Movement. Working with the Free Your Voice after-school program at a local high school, she met the protagonists of the book, two cohorts of high school students who sought to disentangle systems of toxicity from the health risks they posed to their communities. The book is the story of these young activists, and it is told from their perspective. This volume offers a compelling example of community-engaged research.

The first step of this process was working with the residents to develop a de-centered history of the Peninsula. Chapter One describes students’ reactions to a potentially lethal spill at a chemical plant in 2011, which began their interest in tracing a ‘history from the periphery’. Fabricant argues that the environmental toxicity found in the South Baltimore Peninsula communities is a form of state-sanctioned violence that is not accidental but embedded in historically established systems (p.3). The chapter documents the exploitative systems the Free Your Voice students found: a history of “failed development”, from the guano trade in the 1800s to the industrial explosion in the early 20th century. Zoned as a nuisance area, the Peninsula became a space for unregulated industry alongside homes for relocated Black and white immigrant residents. Coal and big oil came in the early 20th century, followed by shipyards after WW2, all accompanied by racialized labor and housing practices. In the 1980s and 90s, the area became a site of “wastelanding”: the area was deemed pollutable and waste industries like incinerators took over. If this dismal history is the beginning of the book, it is certainly not the end. The rest of the book describes the inspiring reactions to this history by students who approached the South Baltimore Peninsula as “a living classroom” and accordingly began to question the dominant narratives and envision alternatives (p. 46).

Chapter Two introduces the Free Your Voice program and its participants at Benjamin Franklin High School. Fabricant describes the methods of the program and her own collaboration with it, leading a participatory research project. Here we see Fabricant’s reliance on and contribution to “decolonizing methodology”, to use Linda Tuhiwai Smith’s term (2012[1999]). Smith famously identified twenty-five different projects for decolonizing Indigenous research. While the protagonists of Fabricant’s book are not Indigenous, her research draws on many of the methods for which Smith advocated. First, the chapter is filled with story-telling and testimonies, where the students recount the difficult lives they and their families have endured, the health problems (so many deaths from asthma!), displacements and homelessness, poverty, labor exploitation. This is a form of re-remembering the past. Second, sharing these stories helped build a community of trust and awaken a “critical consciousness” (Freire 2018[1970]), connecting them to each other, their allies, and their community. As several of the students return to their communities to help organize the next cohorts and interview older residents, we see the intergenerational rootedness of these activists. Their process allowed them to represent themselves and to collectively envision alternative futures. Third, researching and articulating the history of the Peninsula was a form of reclaiming their history. Finally, as the next section makes clear, these students made active interventions to demand structural change. While Fabricant does not disappear from the story, she makes clear that the students are the central protagonists, and this is the heart of the book. We recommend that aspiring ethnographers study Fabricant’s methods as decolonial tools. Her commitment to highlighting the voices of her collaborators provides a profound example of how to decenter the researcher without eliding one’s own positionality. We envision this ethnography being read in graduate seminars that focus on decolonizing anthropology as well as methods courses across the social sciences that aspire to teach community-engaged research.

Youth Politics and Activism: The remaining chapters of the book detail the large successes and perceived setbacks of the projects undertaken by the youth in the Free Your Voice program. Fabricant builds her narrative chronologically, moving through time to trace how each of the campaigns undertaken by the students unfolded. As the Freirean approach to “problem-posing education” took root among those involved in Free Your Voice, these young students began to pose questions about their environment that would ultimately inspire their activism. Chapter Three tells the powerful story of their effort to stall and then stop a proposed initiative to build the “Nation’s Largest Trash-to-Energy Incinerator” in South Baltimore. Co-proposed by the Maryland Department of the Environment and the New York company Energy Answers International, the incinerator was designed to import trash from all over the country and turn this waste into energy. The project claimed to produce renewable energy (ironically, trash is the ‘renewable’ in this schematic), even receiving subsidies of equal value to renewables like wind and solar. Furthermore, industry representatives argued that the incineration of waste would divert it from landfills that are heavy methane producers. The students recognized that opening another incinerator, just a mile from their high school, would continue to worsen their air quality and health outcomes, all the while denouncing the purported ‘greenness’ of the entire initiative. As the Free Your Voice activists mounted their Stop the Incinerator campaign, Fabricant invites readers to observe the adept and inspired way that youth formed alliances with ‘experts’, navigated bureaucracy, and challenged the frameworks of traditional activism. This is particularly evident in the ways students utilized art and theater to articulate their struggle against environmental racism and to eventually “move hearts and minds”, culminating in rap songs and soliloquies performed before the Baltimore Board of Education. Ultimately, the Free Your Voice youth, along with their assembled “Dream Team” that included nonprofit employees, professors, health professionals, and lawyers, was successful in stopping the construction of the incinerator, as part of their overall agenda to bring “fair development” to South Baltimore.

Chapter Four examines another Free Your Voice initiative aimed at fair development that evolved from the students’ growing awareness that access to ownership was essential for controlling land use in South Baltimore. Through a partnership between Towson University, where Fabricant is a professor, and Free Your Voice, the students entered into a year-long seminar, utilizing “participatory design” to develop a vision for a research project that would address housing inequalities (p. 104). They mapped vacant houses and lots, and alongside the South Baltimore Community Land Trust, envisioned turning these spaces into community land trusts. Fabricant explores the emergence of land trusts as emancipatory alternatives to the sharecropping economy that re-enslaved Black communities, thereby articulating the efforts of the Free Your Voice youth to this radical history. The students were again successful in turning these inspired ideas into fiscal reality. They organized to add an Affordable Housing Trust Fund initiative to the Baltimore 20/20 Campaign that called for increased investment in affordable housing. Following this victory, the students created community land trusts, built a community center with a stage, mini golf, and basketball courts, and negotiated a land purchase to construct eight to ten affordable housing units, a kind of “commoning” that poses an environmentally-sound and bottom-up approach to development in their neighborhoods. In this chapter, Fabricant shows what youth political and environmental activism renders – both forward-thinking structural transformation and immediate community renewal, responsive to student desire, visions, and imaginations of other ways to exist in the present.

While Chapters Three and Four recount the resounding successes of these empowered youth, Chapter Five confronts failure, offering insight into the creative and resilient ways that the students responded to defeat. The chapter begins with the Free Your Voice youth learning about composting and zero-waste initiatives that inspire the students to create a Zero-Waste Coalition to pressure the city of Baltimore to change its approach to waste. Again, the students articulated their newest site of activism to fair development for their community, designing, with the help of recruited allies, “Baltimore’s Fair Development Plan for Zero Waste.” Embedded within this plan was a demand that the city not renew their contract with the Baltimore Refuse Energy Systems Company Incinerator (or BRESCO), which burned 80% of county waste, when it expired in 2021. The students organized protests to expose the environmental degradation and health consequences of the incinerator, including a blockade to prevent garbage trucks from bringing their hauls to BRESCO and a massive “die-in” wherein students performed death from pollution on the grounds in front of BRESCO. As the students heightened their efforts, BRESCO did too, hiring lawyers, paying politicians, and orchestrating backdoor deals. In a 3-2 vote, the Baltimore Board of Estimates renewed the BRESCO contract for another ten years. In the wake of this defeat, these younger activists took months to process what had gone wrong and how to move forward. Eventually, the students from Free Your Voice responded with the same coalitionary tactics that had long marked their activism – this time with faculty from local universities – creating a working group on rethinking waste management. Their new focus became “how to drive BRESCO to extinction,” diverting food waste so as to make the incinerator unprofitable (p. 149). In doing so, these students have forced universities to deal with their own culpability as waste producers that disproportionately affect communities of color in Baltimore. Together, these chapters demonstrating the profound successes and potentials in the wake of failure make this book a compelling read for environmental activists engaged in an array of struggles. It functions as an activism primer, offering concrete insights into how to form coalitions, how to design campaigns, and how to build upon both success and failure. And it centers youth, posing an urgent call to include the voices and visions of those who will be tasked with renewing our degraded cities as we face a changing climate in the years to come.

Environmental and Climate Justice: In many ways, this ethnography is a classic account of environmental justice. It details the exposure of a community of color to hazardous waste and heightened pollution, uncovering environmental racism as systematic, historically entrenched, and produced by both institutions and markets. The book traces the rise of a social movement to address these inequities through the platform that environmental justice provides. Scholars have sought to theorize how climate justice evolved out of environmental justice, connecting these overlapping movements in space and time (see Schlosberg and Collins 2014). Whereas environmental justice was and still is, despite its institutionalization, a grassroots movement emerging from the US, notions of climate justice developed across geographies and hierarchies of power with policy makers, scholars, powerful NGOs, and on-the-ground organizers articulating different elements of the coalescing framework. As of now, what and how to teach climate justice is undecided, open to interpretation. But the question of scale is obvious – how do we scale-up environmental justice to address climate change and how do we scale-down climate justice to be attentive to the concerns and demands of communities like South Baltimore? We suggest this is the exact importance of Fabricant’s research. Her work localizes the floating questions of climate justice – about energy, emissions, and fair development as part of a Just Transition – in a specific local context.

This makes Fighting to Breathe an important resource for undergraduate classrooms, particularly in this moment when critical justice approaches to teaching climate change are essential. One of us, Nancy Donald, included Chapter Three examining the campaign to stop the construction of a trash-to-energy incinerator in her syllabus for a Climate Justice course in spring 2023. The piece was taught during the last week of the class when undergraduates were encouraged to get involved in the climate justice movement. The reading from Fabricant re-grounded the class. While many of the materials in the Climate Justice class referred to issues and debates in global settings, Fighting to Breathe awakened students to the climate justice battles that are invariably unfolding in their communities right now. Furthermore, the students, mostly close in age to the protagonists in South Baltimore, were awestruck about what those involved in Free Your Voice were able to accomplish. There was something incredibly powerful in the undergraduates learning from their peers, prompting conversations that were reflective and action oriented. Reading the chapter allowed the undergraduate students in this course to have new insights about waste itself, the ‘renewable’ source for falsified claims of green energy. Not only does this particular case offer students empirical practice in recognizing the greenwashing of supposedly-clean energy alternatives that perpetuate environmental injustice, but it challenges students to consider what happens with the residue of our excess and which communities are affected by our learned tendencies to overconsume.

References:

Freire, Paolo 2018 [1970]. Pedagogy of the Oppressed, Fourth Edition. New York; Bloomsbury Academic.

Schlosberg, David and Lisette B. Collins, 2014. “From Environmental to Climate Justice: Climate Change and the Discourse of Environmental Justice.” WIREs Clim Change 5:359-374.

Smith, Linda Tuhiwai, 2012 [1999]. Decolonizing Methodologies, Research and Indigenous Peoples, Second Edition. London and New York: Zed Books.

Leave a Reply