Socialism in Yiddish: The Jewish Labor Bund in Sweden

by Hakkan Blomqvist

Translated by Blomqvist and Glasser

(Stockholm, Sodertons University, 2021)

The Jewish Labor Bund in Stockholm, Sweden, marching with the Swedish Social-Democrats on the First of May 1946

If one knows anything at all about the Jewish Labor Bund, one associates it with Poland, or Eastern Europe. But Sweden?

The Bund was the first modern Jewish political party, and the largest socialist group, in the Russian Empire. On the eve of the Second World War, it was the strongest Jewish party in Poland.

Hakan Blomqvist tells the story of the Bund in Sweden in Socialism in Yiddish: The Jewish Labor Bund in Sweden (published in Swedish in 2020; English translation, 2022).

Although there is evidence of a small Bundist presence in Sweden as early as 1902, it is only after the Second World War, starting in 1945, that a sizable Bund organization came into being in Sweden.

The story of the Bund in Sweden is at once both heartening and sad: it does not have a happy ending as an organization—although for its members, things mostly turned out well.

Blomqvist, not Jewish, was unable to read his Yiddish sources:

From the outset, it should be noted that I wrote this from the outside. I have no Jewish affiliation, no roots in Jewish culture and speak neither Yiddish nor Hebrew. I came to this topic from research on the Swedish–and to some extent the international–labor movement, as well as on nationalism, racist ideas, and anti-Semitism.

In the Bund archives in the YIVO in New York, he found about 1000 documents on the Swedish Bund, most of them in Yiddish. Unable to read the Yiddish documents (letters, cables, reportage, minutes of meetings, flyers, membership cards, notices in journals, telegrams, newspaper accounts), he was helped by a Dr. Glasser, a specialist in Yiddish: “Box after box, the material went from my hands to Dr. Glasser’s, who read aloud from Yiddish to English, while I took notes and sometimes photographed documents that Glasser later translated in depth in peace and quiet.” From an archive of printed English translations of the original Yiddish material, and from interviews with survivors and their children, he tells the story of the Bund in Sweden.

After the Allied victory in 1945, hundreds of surviving Jewish refugees found their way to Sweden, many of them Bundists. Although social-democratic Sweden was generous in its reception, a great deal of financial support for the Jewish refugees who were Bundists came from the Jewish Labor Committee (JLC) in New York (Frank Wolff in his book, Yiddish Revolutionaries in Migration: The Transnational History of the Jewish Labour Bund, 2021, calls the JLC a “secondary Bundist” organization). Additional financial, and importantly, comradely, moral support came from the Bund organization in New York, as well as from the NY garment workers union—mostly Jewish, whose leadership were in many instances former Bundists—and the NY Workmen’s Circle (another “secondary Bundist” organization).

The Bundist refugees arriving in Sweden were malnourished, hungry, shattered, lonely. Their whole world had been destroyed, their families, friends, their Bund organization, all gone, laid waste. No parents, grandparents, aunts, uncles, siblings, friends, no Bund, nothing. The Holocaust had devoured their all. There was nothing to go back to. Returning to their devastated towns, cities, villages meant further danger–murder by pogromists, hooligans, as happened in Kielce, Poland. Eastern Europe had been all but emptied of its Jews.

After the war and its horrors, now in Sweden, first convalescing, being fed, being brought back to physical health, being placed in refugee camps and care facilities, how to regain some semblance of psychological, social, health? Blomqvist provides a few excerpts from their desperate pleas to the Bund in New York for emotional support. As Blomqvist puts it, “Their letters testified to the catastrophe behind them, to abandonment and despair, but also that someone would hear their cries of distress…”:

Dear Comrades: I write to you and can hardly believe that I am Rosa Rosen [she is 24 years old]…My father was a well-known Bundist [as were all her relatives; she had graduated from a Bund school and had been active in the Bund’s youth organization, Tsukunft]…Now I am completely alone in a new country. I have no friends and know no one…I pray to you in my loneliness, you are my only hope. Your lonely comrade from Lodz.

Another writes that the Swedish Red Cross brought her to Sweden:

…thanks to that, I can become human again…I miss our party, I miss our comrades, I miss our Yiddish literature and our language. My only hope is that I have devoted friends in you…

Two refugee women write to the Bund’s general secretary in New York, promising to resume their activities in the Bund as soon as they regain their strength:

Please do not forget us; perhaps working for the Bund can make us feel better.

After having been reached by a letter from the Bund in New York, another writes:

Dear Comrades: I was so happy to have the first letter from you. You, just you, woke me from my sleep and revived in me what fascism had poisoned. You…gave me a life injection and brought me back to socialism.

From these shattered remnants, the Bund organization in Sweden was formed. It was led by two intrepid Bundists who had been living in Sweden from before the war, Paul Olberg and Sara Mehr.

By the end of the war, Paul Olberg was already 67 years old. According to Blomqvist, he had by that time, as a socialist journalist, a long record of involvement with the social democratic movements in various countries, and a broad acquaintance with their leaders, as for example with Eduard Bernstein and Karl Kautsky in Germany, and in Sweden with the founder of the Swedish social democratic movement, Hjalmar Branting, and with leaders Gustav Moller and Arthur Engberg. He worked as a journalist in Berlin and elsewhere from 1918 to 1933, when, with the accession to power of Hitler, he went to Sweden. There he joined the Swedish Social Democratic party, which came to power in 1932 and ruled for the next 44 years. During and after the war, “Olberg became the important link for the JLC and the Bund in its relief work for comrades….Emanuel Nowogrodski, general secretary of the Bund’s coordinating committee in NY, sent letters to the Bundist refugees in Sweden saying, “Please contact Paul Olberg in Stockholm for material support”:

From Yankef Pat, JLC secretary general, the telegrams and letters arrived in an ever-increasing stream from comrades in need of help. Lists of people on the road, telegrams with arrival times and places were sent to Olberg, as well as money, to provide for their initial time, both necessities and accommodation.

Olberg proposed in September 1945 that he be appointed JLC Swedish representative, which was immediately welcomed in New York. The Bundists in the JLC already knew Olberg, not least the Menshevik veteran Lazar Epstein, whose niece Beba was found by Olberg in a Swedish refugee camp, enabling them to resume contact….Olberg was not modest in emphasizing his good contacts with…Social Democratic politicians up to the top level, such as…the Prime Minister himself.

Olberg was elected President of the Swedish Bund.

“Olberg officially stated before the Swedish Social Democratic Party that the Bund in Sweden numbered 500 members…”(p. 58).

Sara Mehr, elected Vice-President of the Swedish Bund, had, in 1904, at the age of 17, emigrated from Poland to Sweden. She had been a tobacco worker and participated in a long and bitter strike led by the Bund. The strike and the strikers were brutally suppressed by the Russian Cossacks. She left Poland and arrived in Sweden to witness a massive First of May demonstration, with fiery speeches and socialist red flags flying. No government repression, no Cossacks. She was amazed and overjoyed at this freedom. She joined the Swedish Social Democratic party and became active in the Swedish labor movement. Her son rose to prominence in the Swedish labor movement. She retained her Yiddish, Bundist roots. When the Bundist refugees began arriving in Sweden after the war, she was, alongside Olberg, doing all she could to help. She enjoyed acting and performed in Yiddish plays at the various homes that the JLC and the NY Bund had made possible to house the Bundist refugees.

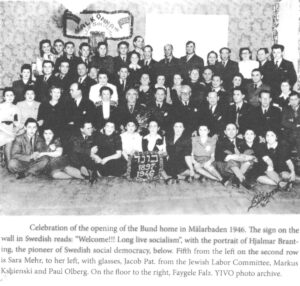

Among the moral and material aid the Bund in Sweden, with the help of the JLC and the Bund in NY, gave to the refugees, their Bund comrades in Sweden, was decent and congenial housing. A Bundist comrade in Sweden writes to the Bund in NY in 1946 that “We have received a house via Olberg and the Swedish Ministry of Foreign Affairs, so that we Bundists can be together” (49). At the opening of the house, there was a speech by Olberg thanking the JLC and the Swedish Social Democrats for their help for the Bundists. The opening included a song composed especially for the occasion called “To Socialism and the Bund.” There were several such houses made available for the Bundist refugees where cultural events, celebrations, and meetings could be held, providing warmth and comradeship for the broken lives of the refugees.

Although Bund membership and activity in Sweden had peaked by 1950, in 1951, a report to the NY Bund from a “chairman’s group” conference in Stockholm dwelled on the Bund’s successes in Sweden, listing “numerous cultural and social events, such as memorials for the ghetto fighters, celebrations of the founding of the Bund, First of May demonstrations with local Social Democratic organizations, literary and musical cultural evenings, activity by members in the Jewish City Councils…distribution of Yiddish literature and magazines, the Bund’s Mendelsohn Library in Stockholm having about 100 borrowers, dotted around the country.” In addition, the report asserted, “Bundist socialist consciousness had deepened among the members” (151-2).

By the 1950s, Bund members in Sweden had, in large numbers, emigrated to Argentina, Canada, Australia, America, Israel, and elsewhere. The Bund in Sweden became a shadow of its former self. As the Bund diminished, quarrels emerged among its leadership, mainly between Olberg and Mehr, further demoralizing what was left of the Bund in Sweden.

Despite a somewhat ignominious end, the Bund, from 1945 to 1950 in Sweden, found housing, gave financial and moral support and succor to the shattered lives of the Bundist survivors who made it to Sweden after the war. An enormous and wonderful achievement. Extremely well-documented and described by Hakan Blomqvist.

Leave a Reply